TWO TREATMENT APPROACHES FOR IMPROVING NARRATIVE RETELL Student

- Slides: 16

TWO TREATMENT APPROACHES FOR IMPROVING NARRATIVE RETELL Student Researcher: Mallory Burke, B. A. Faculty Mentors: Nichole Mulvey, M. S. , CCC-SLP Rebecca Throneburg, Ph. D. , CCC-SLP

INTRODUCTION The ability to tell a story is essential for social interaction and for participation in the academic setting (Gillam & Gillam, 2011; Hayward & Schneider, 2000; Petersen, Gillam, & Gillam, 2008). Narration is a form of storytelling of real or imagined events in which the speaker shares an account in a monologue style while the listener plays a more passive role (Gillam & Gillam, 2011; Petersen, 2010). Children’s narrative ability is closely tied to literacy and academic success and is considered to be the tie between oral and literate language (Gillam & Gillam, 2011; Green & Klecan-Aker, 2012; Kaderavek & Sulzby, 2000).

NARRATIVE SKILLS IN CHILDREN WITH LANGUAGE IMPAIRMENT Narratives are especially difficult for children with language impairment because of the complex demand of narrative tasks (Mc. Fadden, 1998; Petersen, 2010). They are known to produce narratives that are less complex in syntax, semantics, cohesive ties, and story grammar elements (Gillam & Gillam, 2011; Gillam, & Reece, 2012; Green & Kaderavek & Sulzby, 2000, Klecan-Aker, 2012; Peterson, 2010). Children with language delay also have difficulty comprehending narratives (Gillam & Gillam, 2011; Gillam, & Reece, 2012; Petersen, 2010). Difficulties in both the production and comprehension of narratives make it a particularly important target for assessment and intervention (Green & Klecan-Aker, 2012; Mc. Fadden, 1998; Petersen, Gillam, & Gillam, 2008).

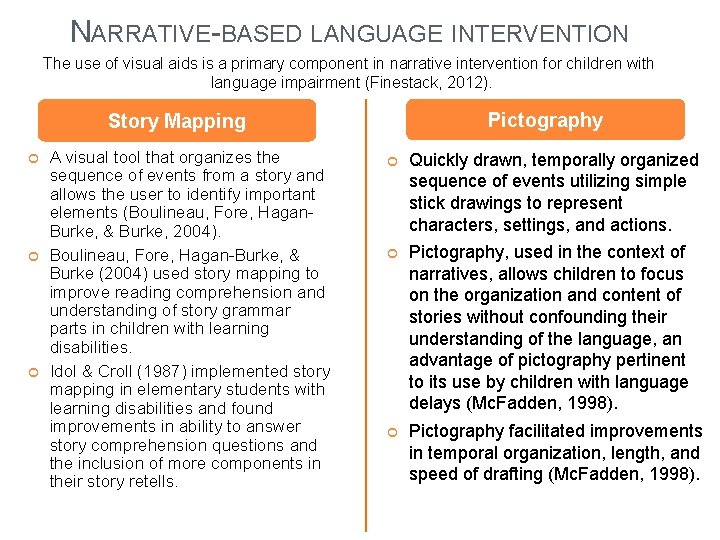

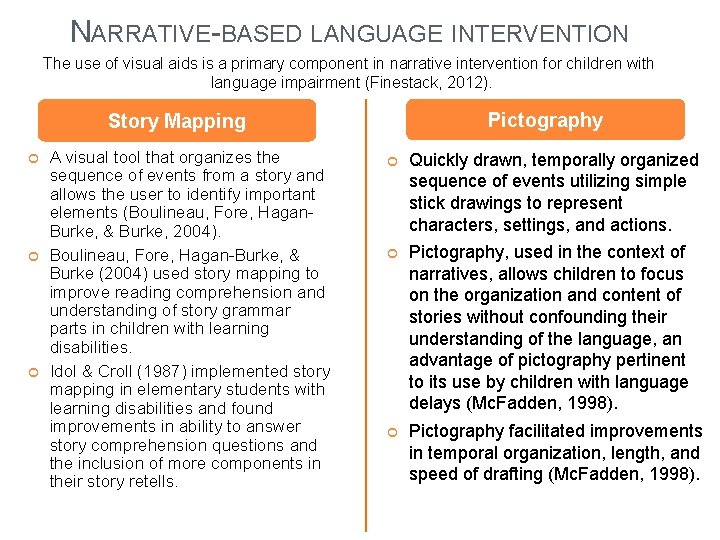

NARRATIVE-BASED LANGUAGE INTERVENTION The use of visual aids is a primary component in narrative intervention for children with language impairment (Finestack, 2012). Pictography Story Mapping A visual tool that organizes the sequence of events from a story and allows the user to identify important elements (Boulineau, Fore, Hagan. Burke, & Burke, 2004). Boulineau, Fore, Hagan-Burke, & Burke (2004) used story mapping to improve reading comprehension and understanding of story grammar parts in children with learning disabilities. Idol & Croll (1987) implemented story mapping in elementary students with learning disabilities and found improvements in ability to answer story comprehension questions and the inclusion of more components in their story retells. Quickly drawn, temporally organized sequence of events utilizing simple stick drawings to represent characters, settings, and actions. Pictography, used in the context of narratives, allows children to focus on the organization and content of stories without confounding their understanding of the language, an advantage of pictography pertinent to its use by children with language delays (Mc. Fadden, 1998). Pictography facilitated improvements in temporal organization, length, and speed of drafting (Mc. Fadden, 1998).

RATIONALE AND RESEARCH QUESTION One previous study that specifically examined the effects of story mapping on story retell Two previous studies on the effects of pictography and story retell No previous study has directly compared the effects of story mapping and pictography interventions on narrative retell ability. Research Question: � Is there a difference between story mapping and pictography intervention methods on narrative retell skills in children with language delay?

PARTICIPANT B. H. 8; 10 3 rd grade Diagnosis: receptive/expressive language delay with language processing deficits � Standard score on the Language Processing Test-3 Elementary = 73 Struggles in reading comprehension � Standard score on the Test of Narrative Language = 67 � Standard score on the Test of Semantic Skills = 59 Enrolled in a regular education classroom but receives special education services.

RESEARCH DESIGN The current study utilized a single subject rapid alternating design. � Conditions were counter-balanced to reduce order effects Baseline Procedure � The clinician selected three books from Marc Brown’s, Arthur Adventure Series. � The clinician read one story per session. � During the story, the clinician stopped to respond to comments or questions made by the participant; no other intervention was implemented during this stage. � Following each story, the clinician prompted the client, “Retell me the story of Arthur’s (book title) including as much important information as you can. ”

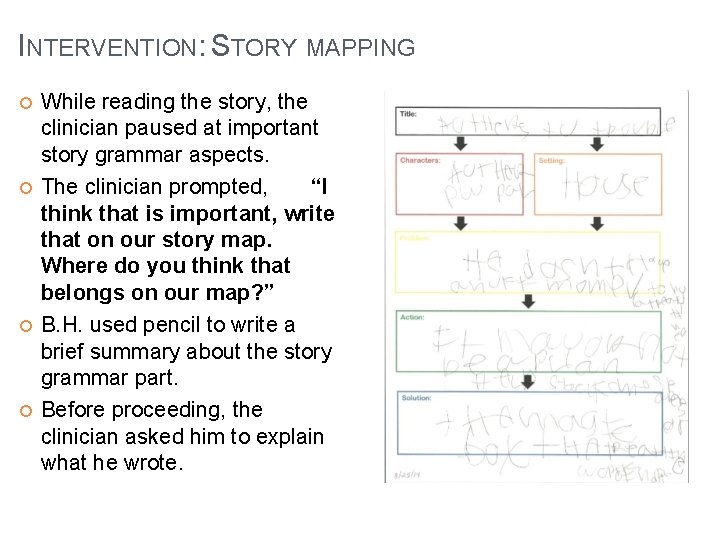

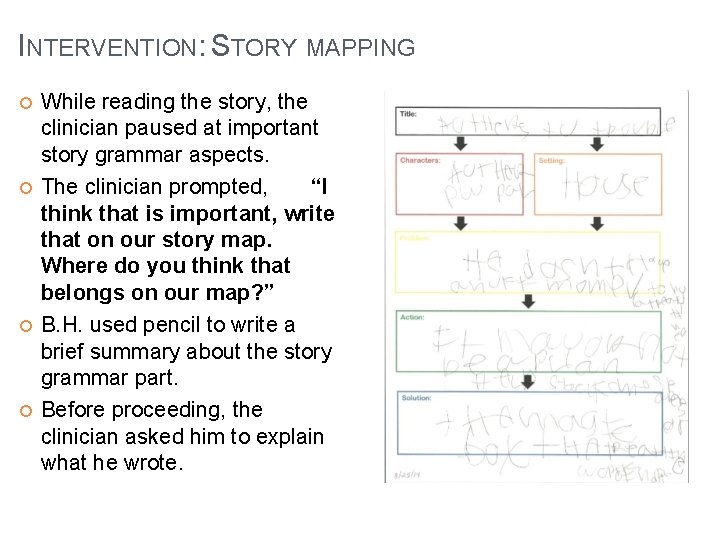

INTERVENTION: STORY MAPPING While reading the story, the clinician paused at important story grammar aspects. The clinician prompted, “I think that is important, write that on our story map. Where do you think that belongs on our map? ” B. H. used pencil to write a brief summary about the story grammar part. Before proceeding, the clinician asked him to explain what he wrote.

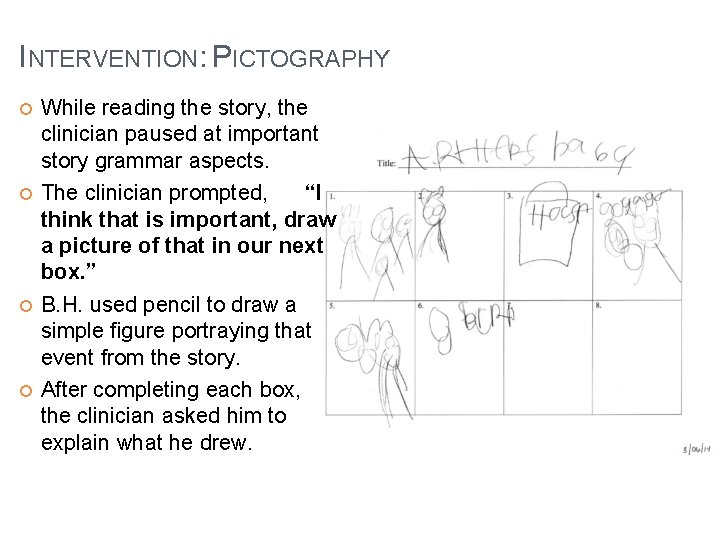

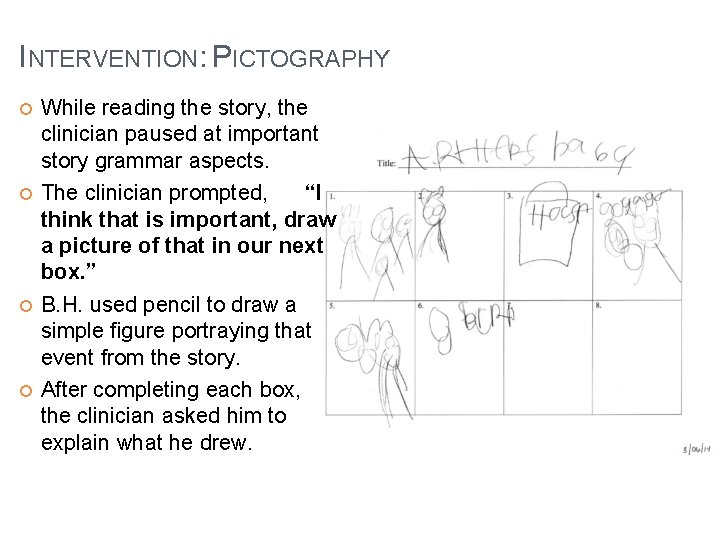

INTERVENTION: PICTOGRAPHY While reading the story, the clinician paused at important story grammar aspects. The clinician prompted, “I think that is important, draw a picture of that in our next box. ” B. H. used pencil to draw a simple figure portraying that event from the story. After completing each box, the clinician asked him to explain what he drew.

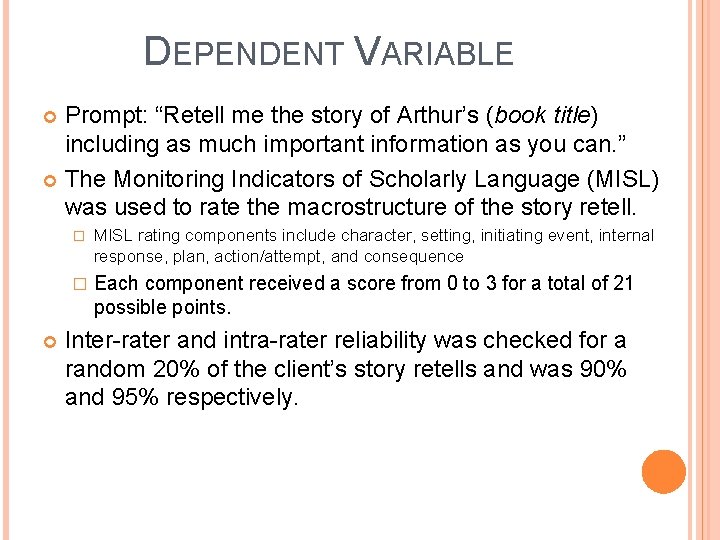

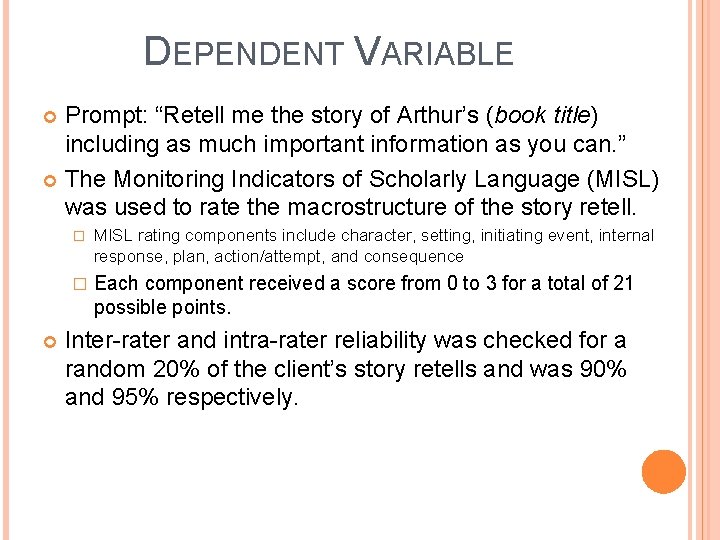

DEPENDENT VARIABLE Prompt: “Retell me the story of Arthur’s (book title) including as much important information as you can. ” The Monitoring Indicators of Scholarly Language (MISL) was used to rate the macrostructure of the story retell. � MISL rating components include character, setting, initiating event, internal response, plan, action/attempt, and consequence � Each component received a score from 0 to 3 for a total of 21 possible points. Inter-rater and intra-rater reliability was checked for a random 20% of the client’s story retells and was 90% and 95% respectively.

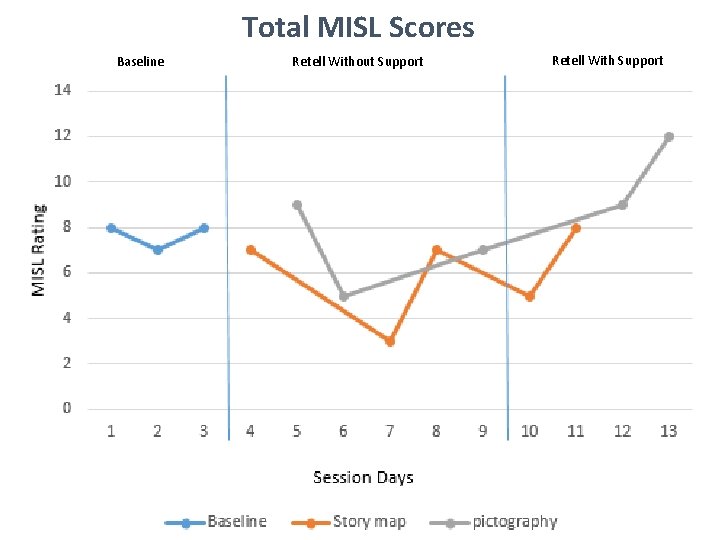

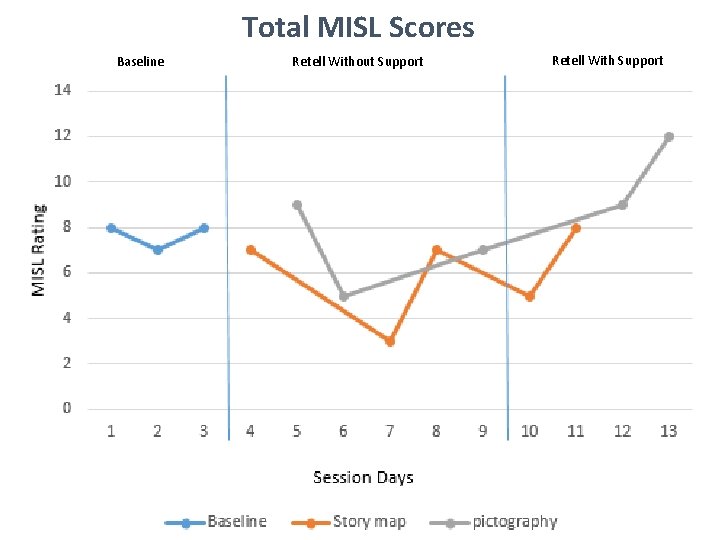

Total MISL Scores Baseline Retell Without Support Retell With Support

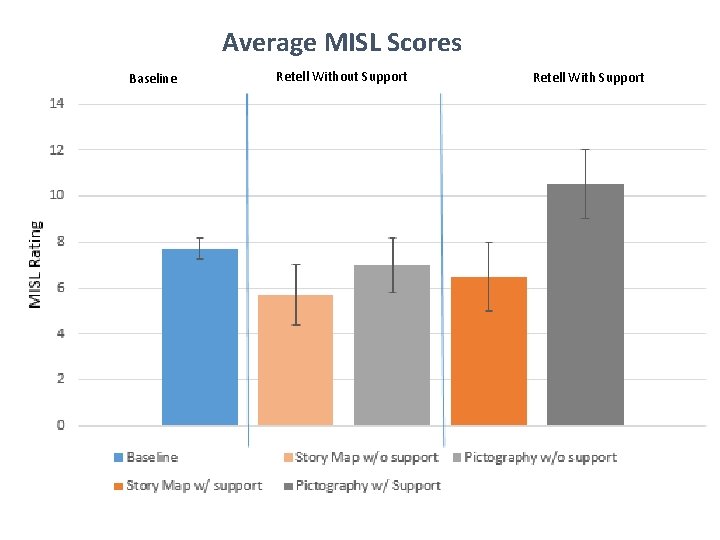

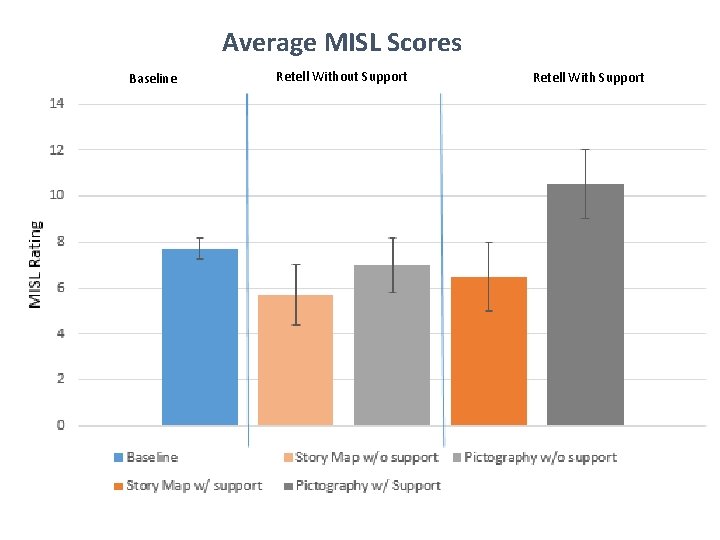

Average MISL Scores Baseline Retell Without Support Retell With Support

DISCUSSION Neither treatment strategy led to gains in retell without the presence of visual support. When the pictography visual was present during the retell, performance was significantly better than baseline and retell without the visual present. Although data indicated increased performance when pictography support was present, the client did not utilize the tool during his retell. The client was introduced to and had experience using both interventions during the previous semester. � However, during the study he did not appear to understand how to use the tools to increase his success. B. H. demonstrated more motivation for using pictography which involved drawing the information versus writing the information in words on the story map.

Strengths Reliability of data collection was ensured by videotape Rapid alternating design allowed for the relative effects of the treatments to be determined in a short period of time when the two treatments were rapidly alternated in treating the same subject. Level of book difficulty remained consistent throughout the treatment Treatment conditions were counter-balanced. Limitations Limited number of participants does not allow the results to be generalized Use of the same book series may have caused the child to become disinterested. Limited amount of time with each treatment strategy B. H. reported that he had previously been exposed to some of the stories. This could have aided his ability to understand the story.

FUTURE RESEARCH Replication with a larger number of subjects Designs to increase generality in findings. � A group design would be beneficial to compare treatment effects with various subjects. Research that examines the effectiveness of pictography and story mapping interventions in the classroom setting. Comprehension is necessary in order to effectively retell a story. Future research that focuses on comprehension in addition to retell would be beneficial. Research that examines how often a student with a language disorder needs to be exposed to a book to master retell and comprehension. More evidence based practice studies are needed with specific focus on: Story mapping and story retell � Pictography and story retell �

REFERENCES Finestack, L. H. (2012). Five principles to consider when providing narrative language intervention to children and adolescents with developmental disabilities. Perspectives on Language Learning and Education, 19(1), 147 -154. Gillam, S. L. , & Gillam, R. B. (2011). Assessment and treatment of narratives: The rest of the story. Presentation, October 2011. Gillam, S. L. , Gillam, R. B. , & Reece, K. (2012). Language outcomes of contextualized and decontextualized language intervention: Results of an early efficacy study. Language, Speech, and Hearing in Schools. 43(1). 276 -291. Green, L. B. , & Klecan-Aker, J. S. (2012). Teaching story grammar components to increase oral narrative ability: A group intervention study. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 28(3), 263 -276. Hayward, D. , & Schneider, P. (2000). Effectiveness of teaching story grammar knowledge to pre-school children with language: A exploratory study. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 16(3), 255 -284. Kaderavek, J. N. , & Sulzby, E. (2000). Narrative production by children with and without specific language impairment: Oral narratives and emergent readings. Journal of Speech, Lanugage, and Hearning Research, 43(1), 34 -49. Idol, L. , & Croll, V. J. (1987). Story-mapping training as a means of improving reading comprehension. ) Learning Disability Quarterly, 10(3), 214 -229. Mc. Fadden, T. U. (1998). The immediate effects of pictographic representation on children’s narratives. Child Language Teaching and Therapy. 14(1). 51 -67. Peterson, D. B. (2010). A systematic review of narrative-based language intervention with children who have language impairment. Communication Disorders Quarterly. 32(4). 207 -220. Petersen, D. B. , Gillam, S. L. , & Gillam, R. B. (2008). Emerging procedures in narrative assessment: The index of narrative complexity. Top Language Disorders, 28(2), 115130.