Economic Growth Economic growth refers to an increase

- Slides: 26

Economic Growth • Economic growth refers to an increase in the total output of an economy. Defined by some economists as the increase of real GDP per capita. • Modern economic growth is the period of rapid and sustained increase in real output per capita that began in the Western World with the Industrial Revolution. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

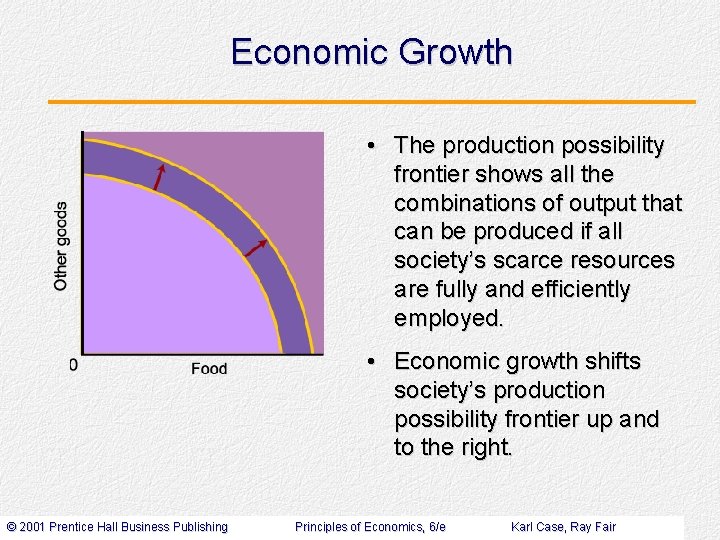

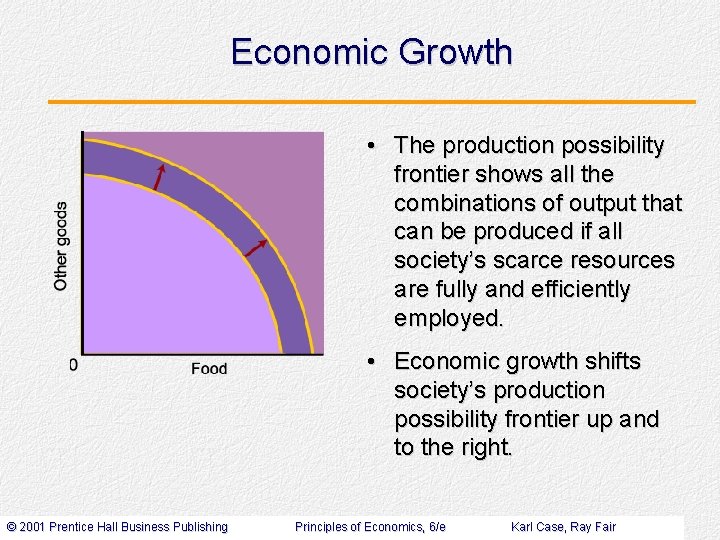

Economic Growth • The production possibility frontier shows all the combinations of output that can be produced if all society’s scarce resources are fully and efficiently employed. • Economic growth shifts society’s production possibility frontier up and to the right. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

The Growth Process: From Agriculture to Industry • Before the Industrial Revolution in Great Britain, every society in the world was agrarian. • Beginning in England around 1750, technical change and capital accumulation increased productivity in two important industries: agriculture and textiles. • More could be produced with fewer resources, leading to new products, more output, and wider choice. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

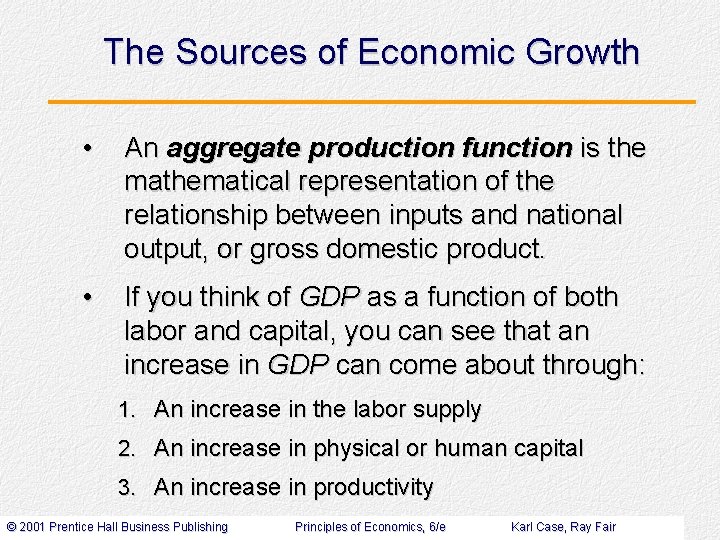

The Sources of Economic Growth • An aggregate production function is the mathematical representation of the relationship between inputs and national output, or gross domestic product. • If you think of GDP as a function of both labor and capital, you can see that an increase in GDP can come about through: 1. An increase in the labor supply 2. An increase in physical or human capital 3. An increase in productivity © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

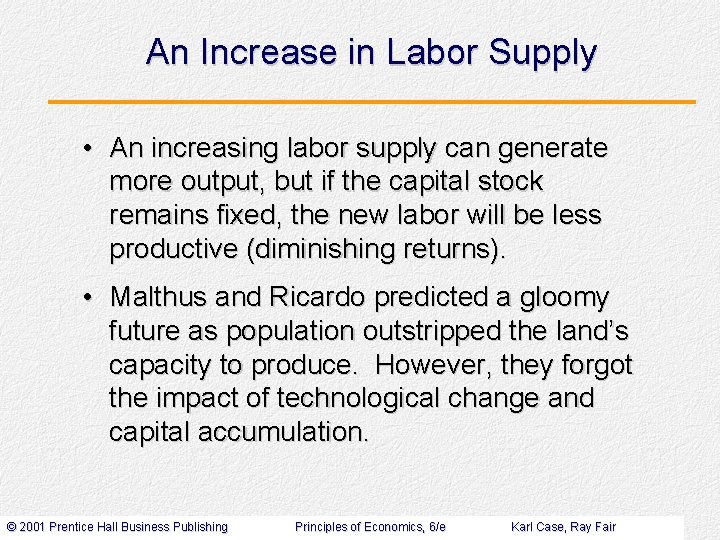

An Increase in Labor Supply • An increasing labor supply can generate more output, but if the capital stock remains fixed, the new labor will be less productive (diminishing returns). • Malthus and Ricardo predicted a gloomy future as population outstripped the land’s capacity to produce. However, they forgot the impact of technological change and capital accumulation. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

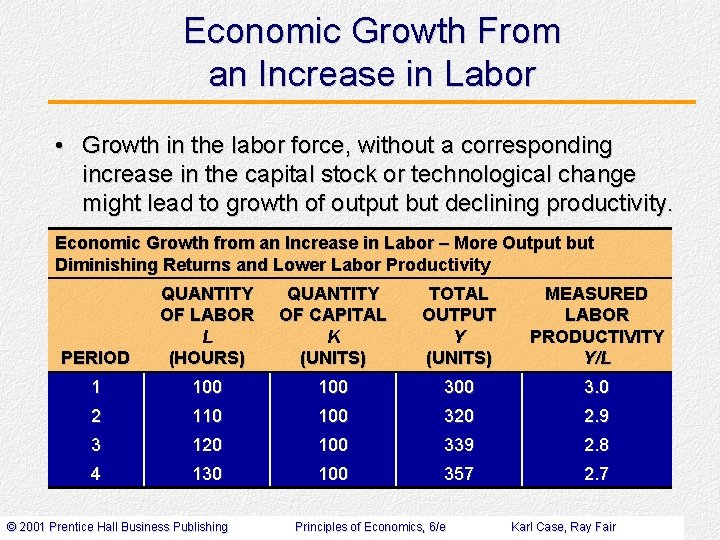

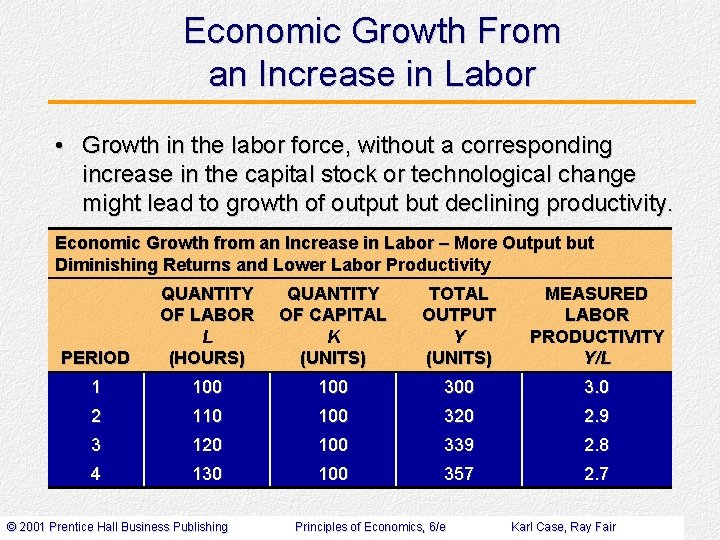

Economic Growth From an Increase in Labor • Growth in the labor force, without a corresponding increase in the capital stock or technological change might lead to growth of output but declining productivity. Economic Growth from an Increase in Labor – More Output but Diminishing Returns and Lower Labor Productivity PERIOD QUANTITY OF LABOR L (HOURS) QUANTITY OF CAPITAL K (UNITS) TOTAL OUTPUT Y (UNITS) MEASURED LABOR PRODUCTIVITY Y/L 1 100 300 3. 0 2 110 100 320 2. 9 3 120 100 339 2. 8 4 130 100 357 2. 7 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

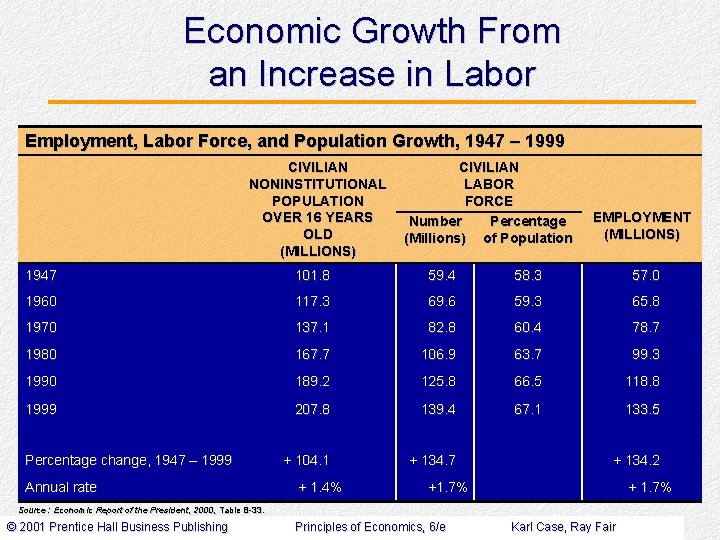

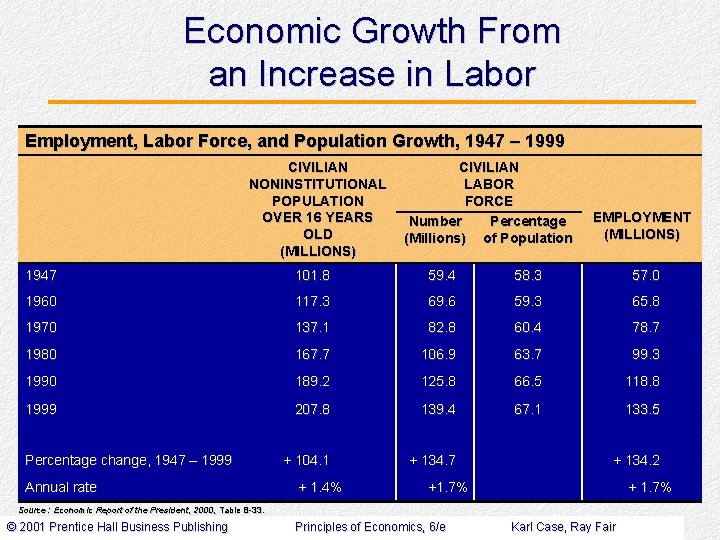

Economic Growth From an Increase in Labor Employment, Labor Force, and Population Growth, 1947 – 1999 CIVILIAN NONINSTITUTIONAL POPULATION OVER 16 YEARS OLD (MILLIONS) CIVILIAN LABOR FORCE Number Percentage (Millions) of Population EMPLOYMENT (MILLIONS) 1947 101. 8 59. 4 58. 3 57. 0 1960 117. 3 69. 6 59. 3 65. 8 1970 137. 1 82. 8 60. 4 78. 7 1980 167. 7 106. 9 63. 7 99. 3 1990 189. 2 125. 8 66. 5 118. 8 1999 207. 8 139. 4 67. 1 133. 5 + 104. 1 + 134. 7 Percentage change, 1947 – 1999 Annual rate + 1. 4% + 134. 2 +1. 7% + 1. 7% Source: Economic Report of the President, 2000, Table B-33. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

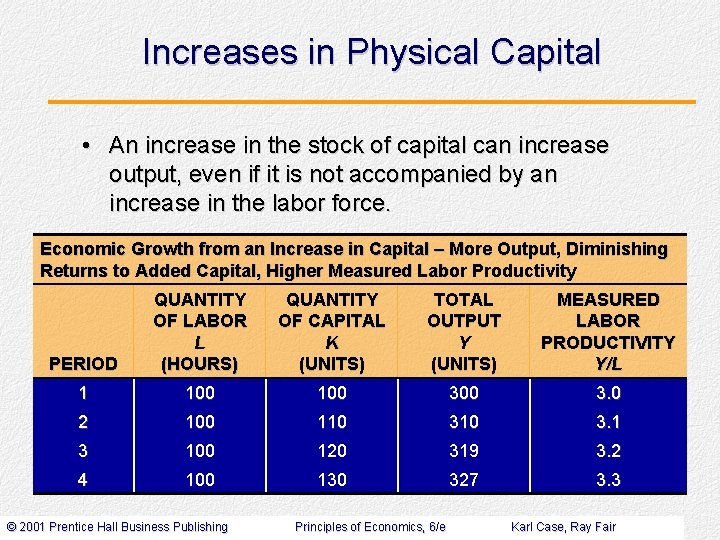

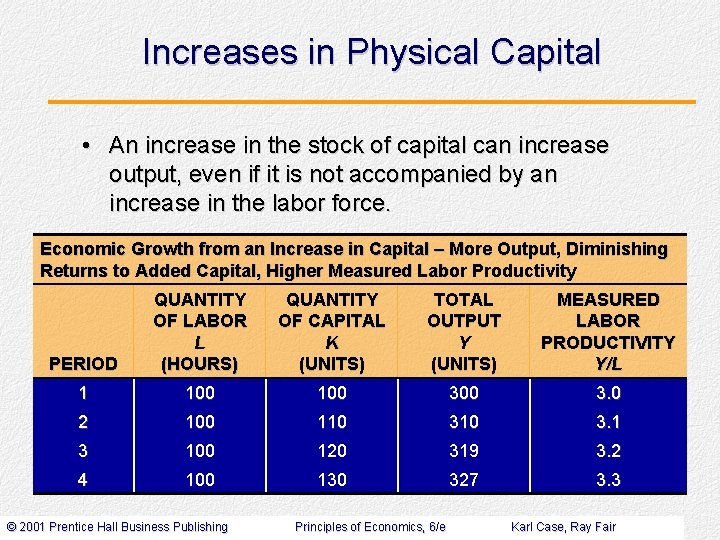

Increases in Physical Capital • An increase in the stock of capital can increase output, even if it is not accompanied by an increase in the labor force. Economic Growth from an Increase in Capital – More Output, Diminishing Returns to Added Capital, Higher Measured Labor Productivity PERIOD QUANTITY OF LABOR L (HOURS) QUANTITY OF CAPITAL K (UNITS) TOTAL OUTPUT Y (UNITS) MEASURED LABOR PRODUCTIVITY Y/L 1 100 300 3. 0 2 100 110 3. 1 3 100 120 319 3. 2 4 100 130 327 3. 3 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

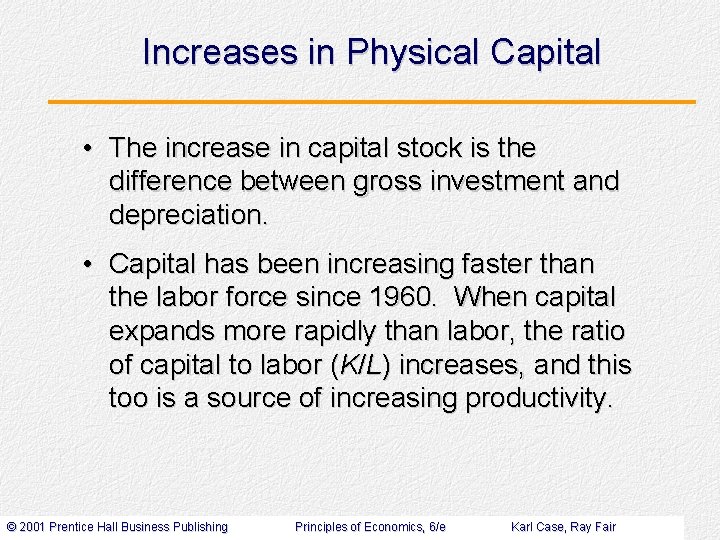

Increases in Physical Capital • The increase in capital stock is the difference between gross investment and depreciation. • Capital has been increasing faster than the labor force since 1960. When capital expands more rapidly than labor, the ratio of capital to labor (K/L) increases, and this too is a source of increasing productivity. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

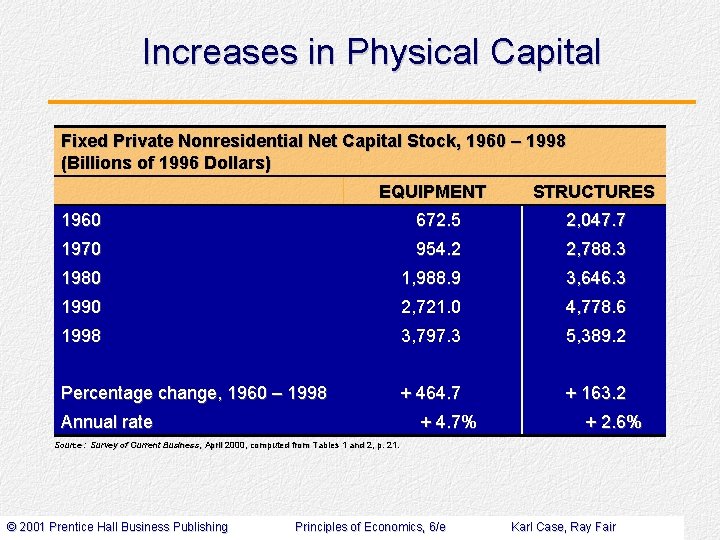

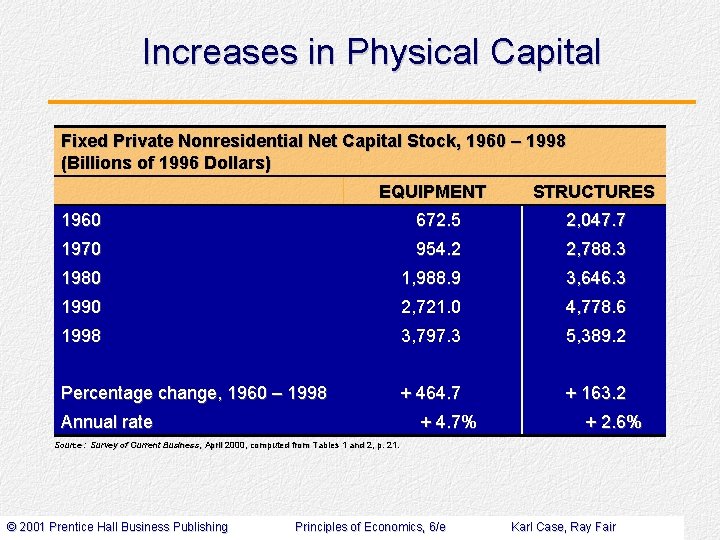

Increases in Physical Capital Fixed Private Nonresidential Net Capital Stock, 1960 – 1998 (Billions of 1996 Dollars) EQUIPMENT STRUCTURES 1960 672. 5 2, 047. 7 1970 954. 2 2, 788. 3 1980 1, 988. 9 3, 646. 3 1990 2, 721. 0 4, 778. 6 1998 3, 797. 3 5, 389. 2 Percentage change, 1960 – 1998 + 464. 7 + 163. 2 Annual rate + 4. 7% + 2. 6% Source: Survey of Current Business, April 2000, computed from Tables 1 and 2, p. 21. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

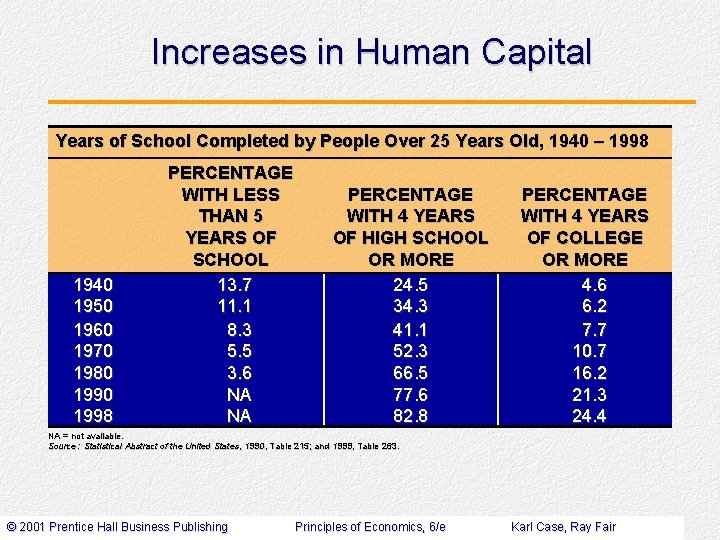

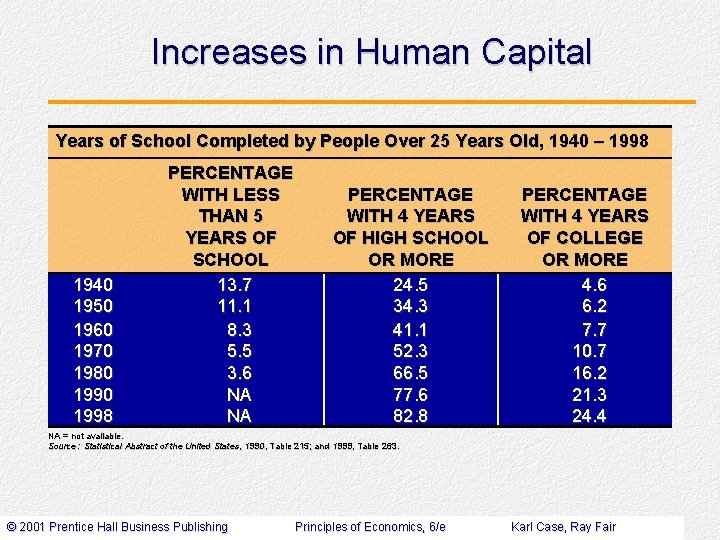

Increases in Human Capital Years of School Completed by People Over 25 Years Old, 1940 – 1998 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1998 PERCENTAGE WITH LESS THAN 5 YEARS OF SCHOOL 13. 7 11. 1 8. 3 5. 5 3. 6 NA NA PERCENTAGE WITH 4 YEARS OF HIGH SCHOOL OR MORE 24. 5 34. 3 41. 1 52. 3 66. 5 77. 6 82. 8 PERCENTAGE WITH 4 YEARS OF COLLEGE OR MORE 4. 6 6. 2 7. 7 10. 7 16. 2 21. 3 24. 4 NA = not available. Source: Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1990, Table 215; and 1999, Table 263. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

Increases in Productivity • Growth that cannot be explained by increases in the quantity of inputs can be explained only by an increase in the productivity of those inputs. • The productivity of an input is the amount produced per unit of an input. • Factors that affect the productivity of an input include technological change, other advances in knowledge, and economies of scale. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

Increases in Productivity • • Technological change affects productivity in two stages: • First there is an advance in knowledge, or an invention. • Then there is innovation, or the use of new knowledge to produce a new product or to produce an existing product more efficiently. There are capital-saving innovations, and labor-saving innovations. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

Increases in Productivity • External economies of scale are cost savings that result from increases in the size of industries. • Production abatement requirements divert capital and labor from the production of measured output, therefore reducing measured productivity. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

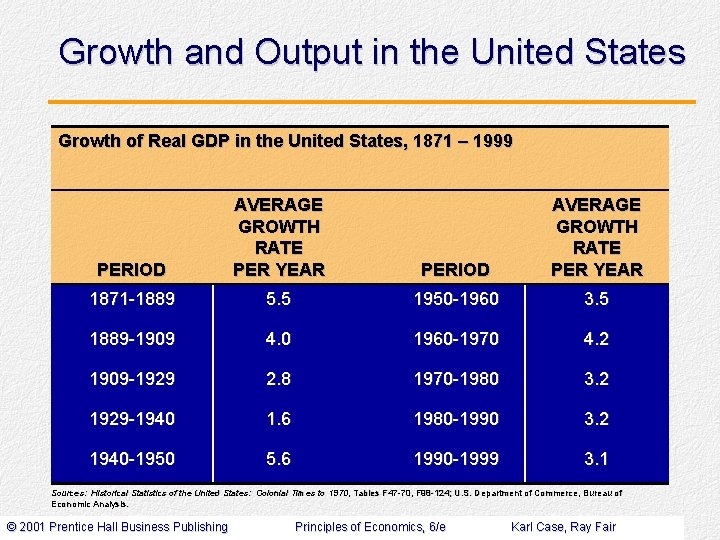

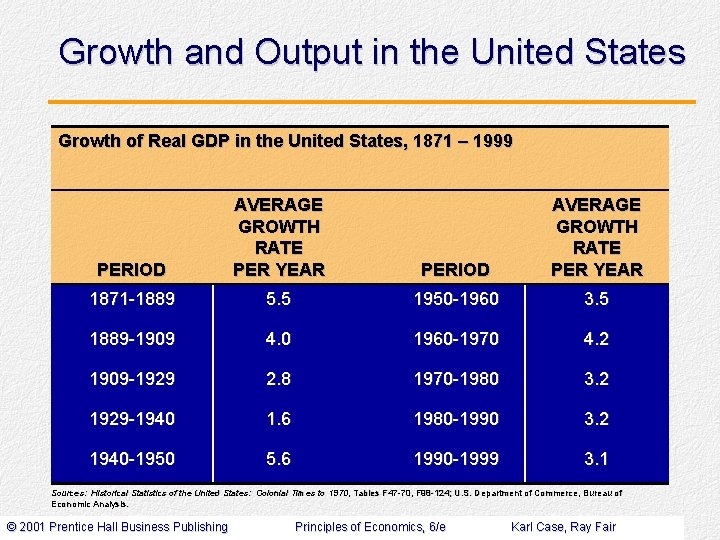

Growth and Output in the United States Growth of Real GDP in the United States, 1871 – 1999 PERIOD AVERAGE GROWTH RATE PER YEAR 1871 -1889 5. 5 1950 -1960 3. 5 1889 -1909 4. 0 1960 -1970 4. 2 1909 -1929 2. 8 1970 -1980 3. 2 1929 -1940 1. 6 1980 -1990 3. 2 1940 -1950 5. 6 1990 -1999 3. 1 Sources: Historical Statistics of the United States: Colonial Times to 1970, Tables F 47 -70, F 98 -124; U. S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of Economic Analysis. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

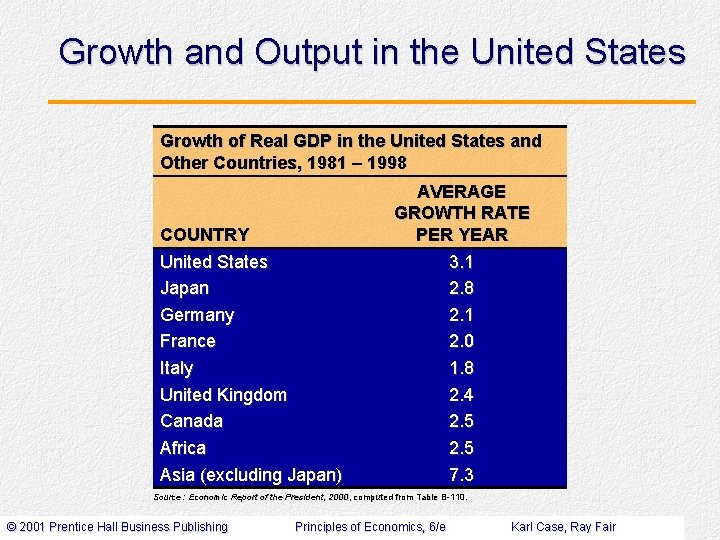

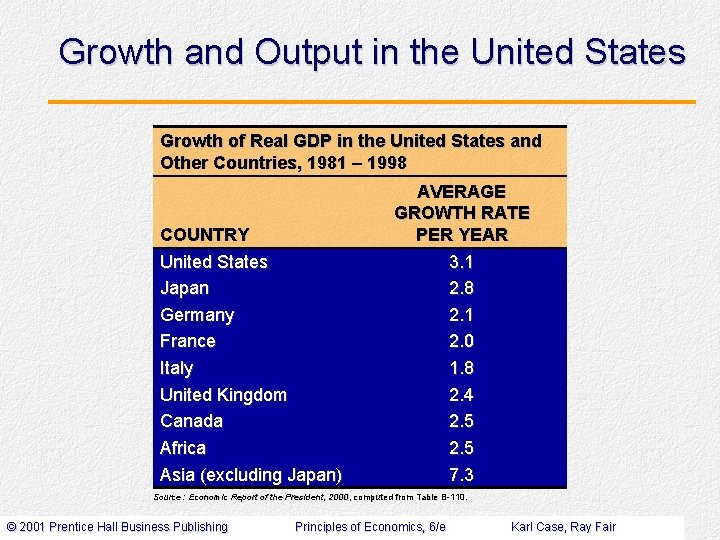

Growth and Output in the United States Growth of Real GDP in the United States and Other Countries, 1981 – 1998 COUNTRY United States Japan Germany France Italy United Kingdom Canada Africa Asia (excluding Japan) AVERAGE GROWTH RATE PER YEAR 3. 1 2. 8 2. 1 2. 0 1. 8 2. 4 2. 5 7. 3 Source: Economic Report of the President, 2000, computed from Table B-110. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

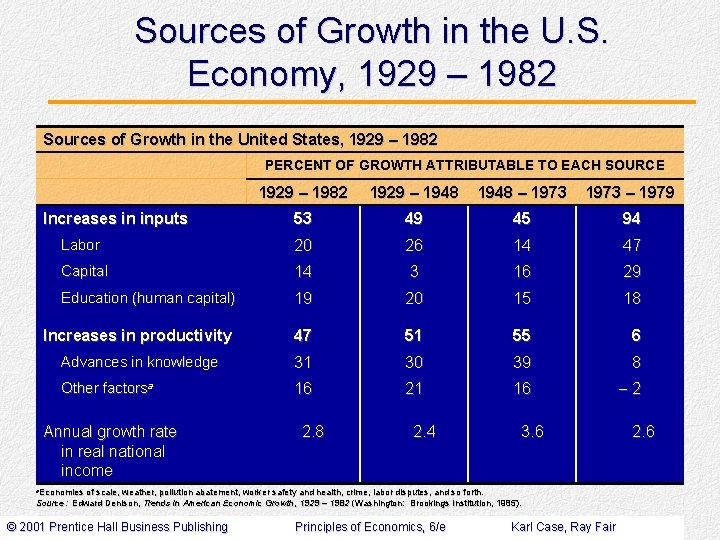

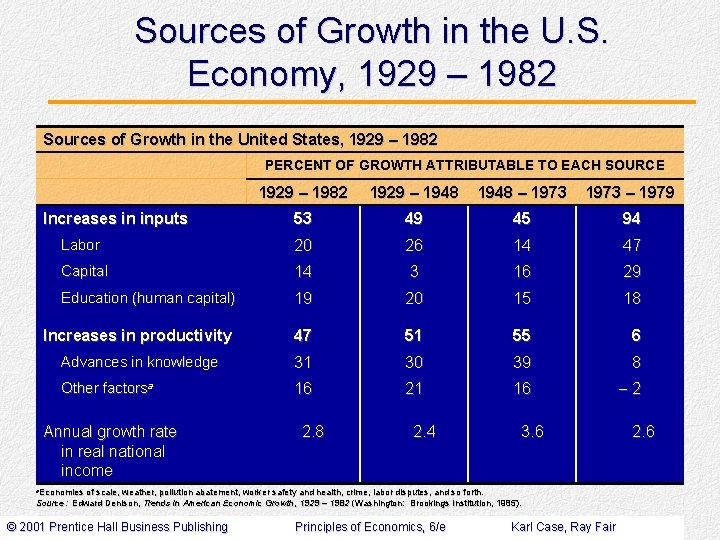

Sources of Growth in the U. S. Economy, 1929 – 1982 Sources of Growth in the United States, 1929 – 1982 PERCENT OF GROWTH ATTRIBUTABLE TO EACH SOURCE 1929 – 1982 1929 – 1948 – 1973 – 1979 53 49 45 94 Labor 20 26 14 47 Capital 14 3 16 29 Education (human capital) 19 20 15 18 Increases in productivity 47 51 55 6 Advances in knowledge 31 30 39 8 Other factorsa 16 21 16 -2 Increases in inputs Annual growth rate in real national income 2. 8 2. 4 3. 6 a. Economies of scale, weather, pollution abatement, worker safety and health, crime, labor disputes, and so forth. Source: Edward Denison, Trends in American Economic Growth, 1929 – 1982 (Washington: Brookings Institution, 1985). © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair 2. 6

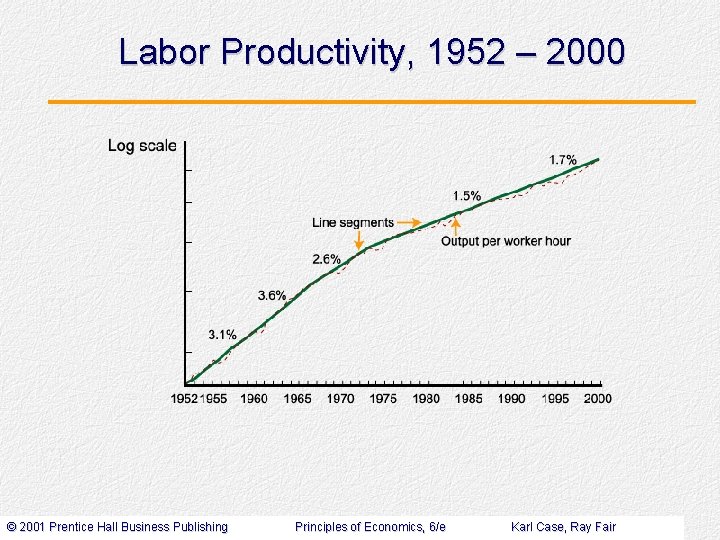

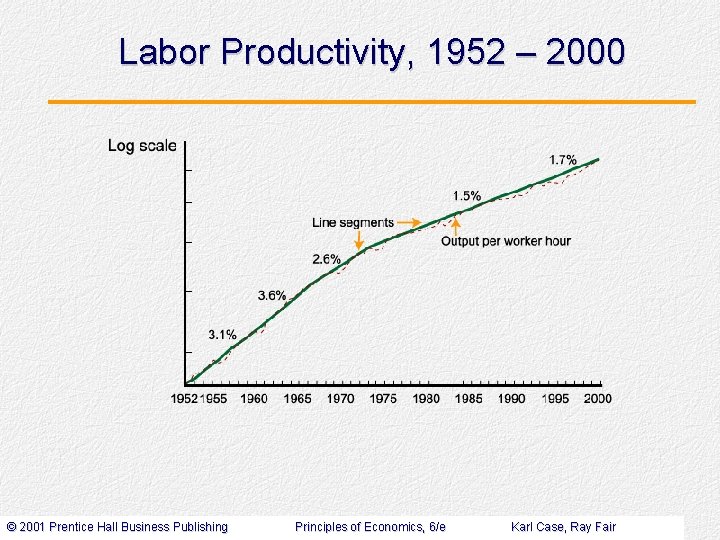

Labor Productivity, 1952 – 2000 © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

Labor Productivity, 1952 – 2000 • Some of the explanations for the slowdown in productivity growth in the 1970 s include: • a low rate of saving • increased environmental and government regulations • lack of spending in R&D • high energy costs • However, many of these factors turned around in the 1980 s and 1990 s yet productivity growth remained low. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

Economic Growth and Public Policy • Policy provisions to improve the quality of education include the new Education Individual Retirement Account that allows savings to earn tax free returns as long as the balance is used to pay for educational expenses. • Policies to increase the saving rate include individual retirement accounts that accumulate earnings without paying income tax. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

Economic Growth and Public Policy • The amount of capital accumulation is ultimately constrained by its rate of saving. • The tax system and the social security system in the United States are biased against saving. • Some public finance economists favor shifting to a system of consumption taxation rather than income taxation to reduce the tax burden on saving. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

Economic Growth and Public Policy • Other public policies to stimulate economic growth include: • policies to stimulate investment • policies to increase research and development • reduced regulations • industrial policy, or government involvement in the allocation of capital across manufacturing sectors. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

The Pro-Growth Argument • Advocates of growth believe growth is progress. • New technologies and production methods lead to new and better products. Capital accumulation and new technology improve the quality of life. • In 1995, real GDP per capita was more than twice what it was in 1950. Since the 1950 s, incomes have grown twice as fast as prices. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

The Pro-Growth Argument • Advocates of growth believe growth is progress. • Growth gives us more choices. • New technologies and production methods lead to new and better products. Capital accumulation and new technology improve the quality of life. • Since the 1950 s, incomes have grown twice as fast as prices so we can buy that much more. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

The Pro-Growth Argument • Growth saves the most valuable commodity—time. • Growth also improves the quality of things that yield satisfaction directly. • Growth produces jobs and higher incomes. With higher incomes we can better afford the sacrifices needed to help the poor. • When population growth is not accompanied by growth in output, unemployment and poverty increase. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

The Anti-Growth Argument • Growth has negative effects on the quality of life. • Growth encourages the creation of artificial needs. • Growth means the rapid depletion of a finite quantity of resources. • Growth requires an unfair income distribution and propagates it. © 2001 Prentice Hall Business Publishing Principles of Economics, 6/e Karl Case, Ray Fair

Economic growth vs economic development

Economic growth vs economic development Conclusion of growth and development

Conclusion of growth and development Growth analysis

Growth analysis An infant's growth refers to changes in

An infant's growth refers to changes in Urie bronfenbrenner contextual view of development

Urie bronfenbrenner contextual view of development Caput succedaneum vs cephalohematoma

Caput succedaneum vs cephalohematoma Synchronous growth

Synchronous growth Growth refers to

Growth refers to Introduction for business environment

Introduction for business environment Economic exposure

Economic exposure Primary growth and secondary growth in plants

Primary growth and secondary growth in plants Chapter 35 plant structure growth and development

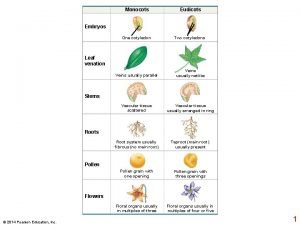

Chapter 35 plant structure growth and development Monocots eudicots

Monocots eudicots Neoclassical growth theory vs. endogenous growth theory

Neoclassical growth theory vs. endogenous growth theory Geometric growth vs exponential growth

Geometric growth vs exponential growth Growthchain

Growthchain Organic vs inorganic growth

Organic vs inorganic growth Models of global sustainable development ppt

Models of global sustainable development ppt Solow model of economic growth

Solow model of economic growth National development

National development Rostows stages of economic growth

Rostows stages of economic growth Importance of economic growth

Importance of economic growth Economic growth is defined as

Economic growth is defined as Long run economic growth

Long run economic growth Economic growth trends

Economic growth trends Solow's model of economic growth

Solow's model of economic growth Solow's model of economic growth

Solow's model of economic growth