Conceptualization and Measurement of Flexicurity in a Comparative

![Measures using ECHP • Job Mobility (JM) – Occupational mobility [JM] (based on occupational Measures using ECHP • Job Mobility (JM) – Occupational mobility [JM] (based on occupational](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/aa7ae0cc177a18622fda8eb1991cd660/image-10.jpg)

- Slides: 16

Conceptualization and Measurement of Flexicurity in a Comparative Perspective Seminar Flexicurity Network Copenhagen, June 9, 2006 Ruud. J. A. Muffels & Ton Wilthagen 1. Job mobility and Work Security: Trade-Off or Double-Bind 2. Flexicurity in a life course perspective Tilburg University, Department of Social and Cultural Studies / OSA – Institute for Labour Studies

Research focus in both projects • Exploring the role and performance of welfare states / policy regimes in maintaining flexibility and work and income security using longitudinal data (paneldata; lifecourse-data) • Based on a dynamic approach: define flexicurity not in a static way but in a lifecourse perspective • Define a broad set of dynamic ‘outcome’ indicators on both: flexibility and security. Not EPL but tenure or job mobility should be used as indicators

Life course proofing of flexicurity arrangements • Life-course proofing: long-term effects of working time arrangements such as part-time work, career breaks (care and educational leave schemes) and working in non-standard jobs. • Short and long-term effects on future wages and income; on participation in employment; on occupational level of jobs (careers), on job quality, life satisfaction and health • Main underlying question: Is there a ‘trade-off’ or a ‘double bind’ relationship between the aims of creating a flexible labor market and safeguarding employment security for all people over their life-time?

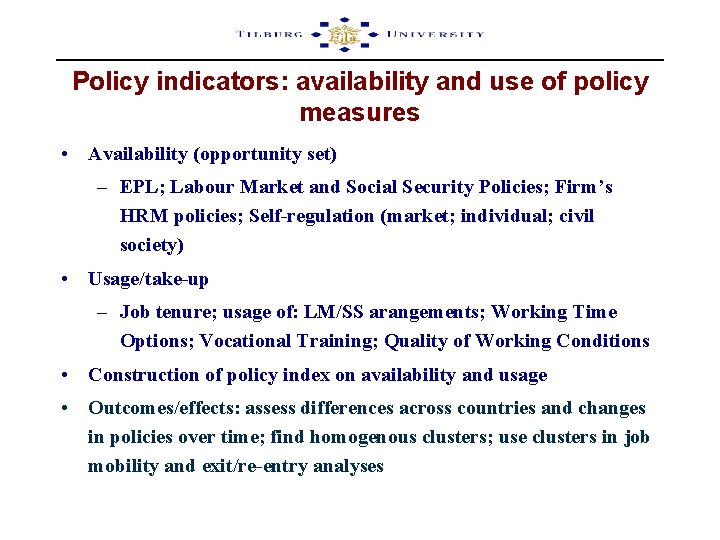

Dynamic indicators Flexibility: – Job-to-job mobility (internal, external); – Professional status mobility; – Contractmobility Work Security: – Employment stability; unempl. spells; – Exit and (Re)-Entry: w. r. t. employment; working hours; quality of work – Income security; well-being; quality of life; social participation & integration (e. g. spells of low/high income, well-being etc. );

Policy indicators: availability and use of policy measures • Availability (opportunity set) – EPL; Labour Market and Social Security Policies; Firm’s HRM policies; Self-regulation (market; individual; civil society) • Usage/take-up – Job tenure; usage of: LM/SS arangements; Working Time Options; Vocational Training; Quality of Working Conditions • Construction of policy index on availability and usage • Outcomes/effects: assess differences across countries and changes in policies over time; find homogenous clusters; use clusters in job mobility and exit/re-entry analyses

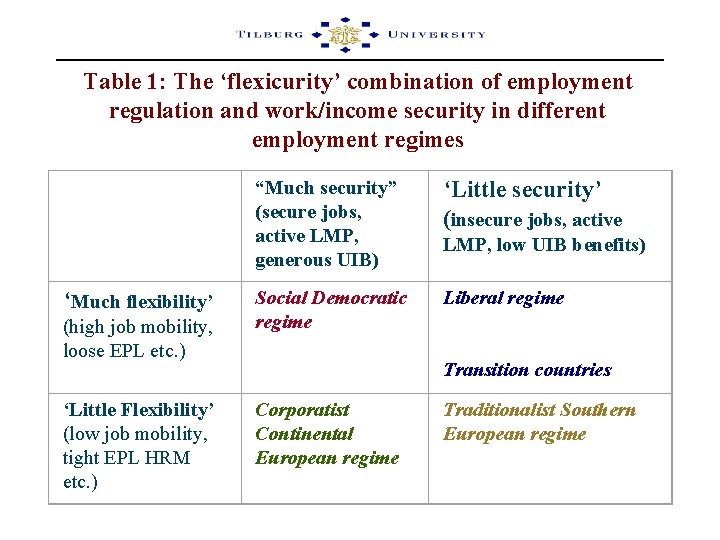

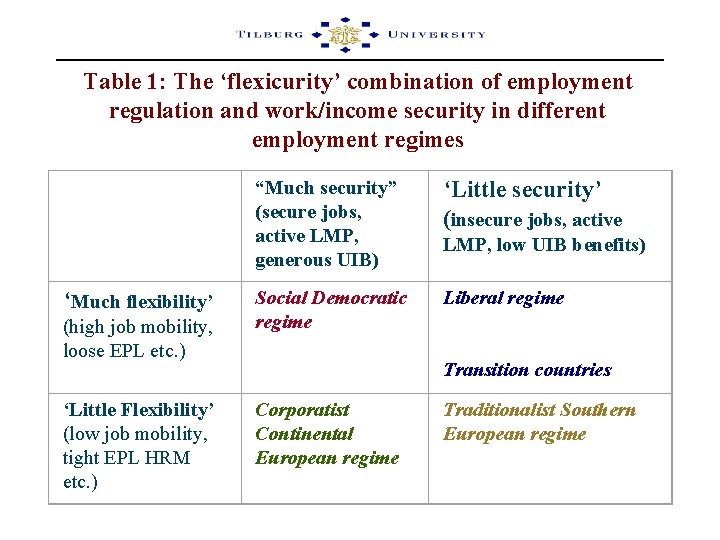

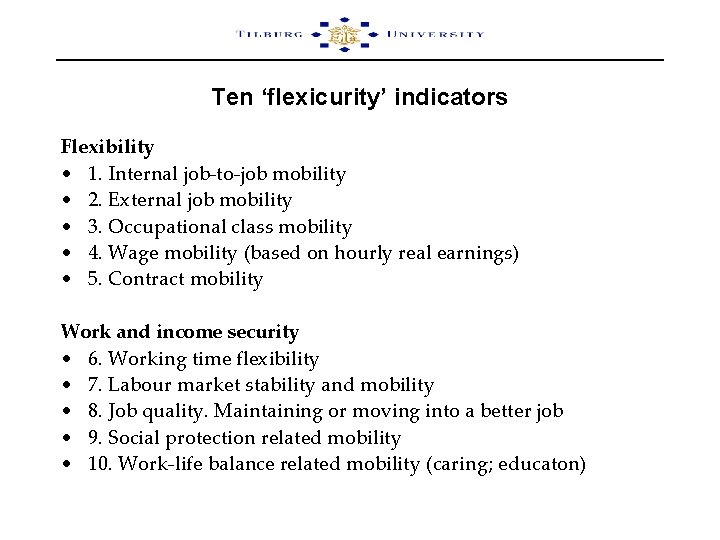

Table 1: The ‘flexicurity’ combination of employment regulation and work/income security in different employment regimes ‘Much flexibility’ (high job mobility, loose EPL etc. ) ‘Little Flexibility’ (low job mobility, tight EPL HRM etc. ) “Much security” (secure jobs, active LMP, generous UIB) ‘Little security’ (insecure jobs, active Social Democratic regime Liberal regime LMP, low UIB benefits) Transition countries Corporatist Continental European regime Traditionalist Southern European regime

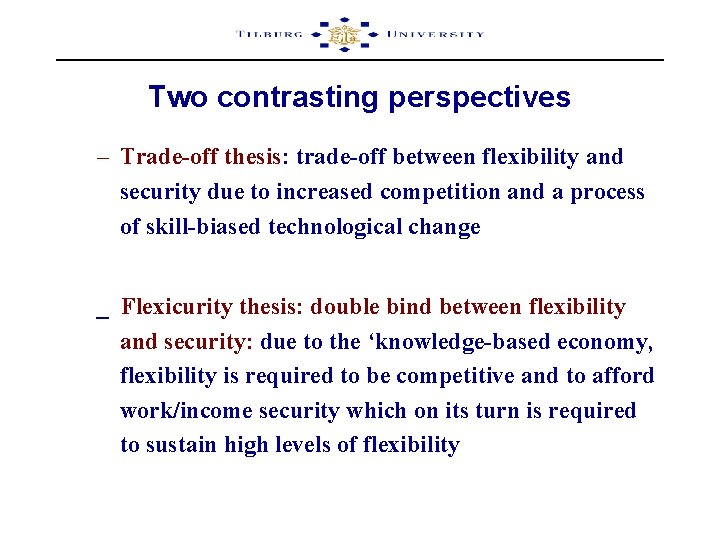

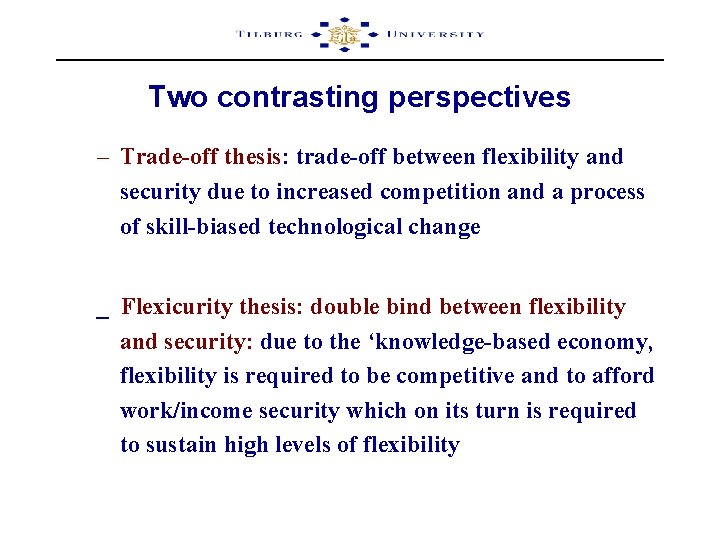

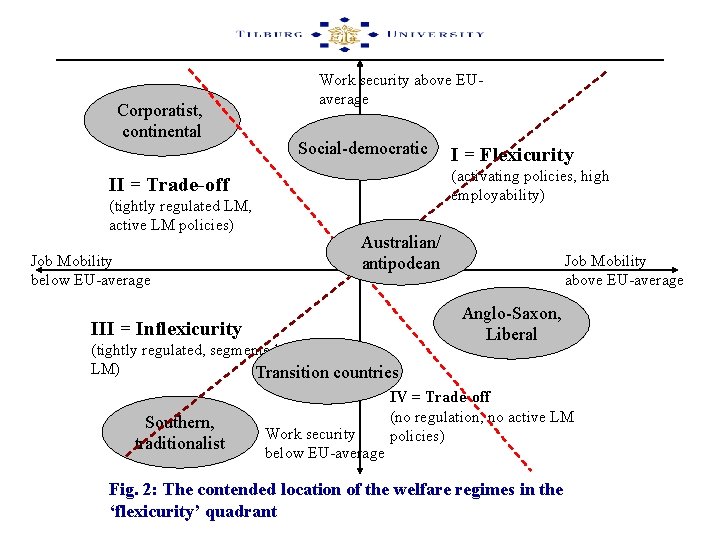

Two contrasting perspectives – Trade-off thesis: trade-off between flexibility and security due to increased competition and a process of skill-biased technological change _ Flexicurity thesis: double bind between flexibility and security: due to the ‘knowledge-based economy, flexibility is required to be competitive and to afford work/income security which on its turn is required to sustain high levels of flexibility

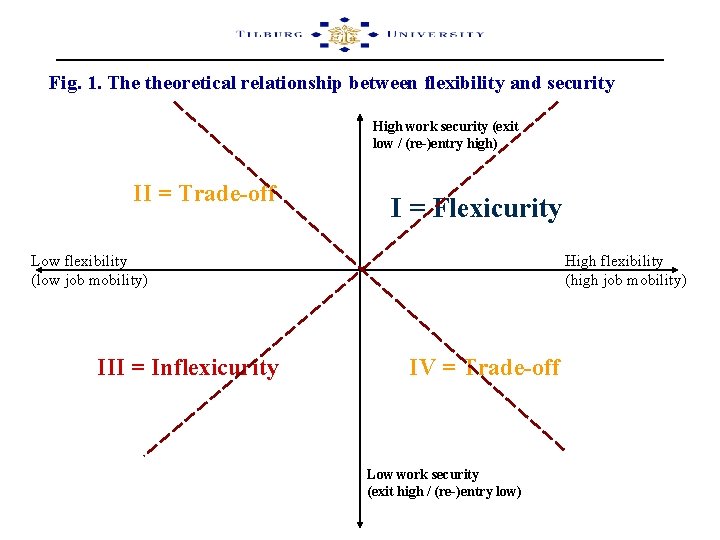

Fig. 1. The theoretical relationship between flexibility and security High work security (exit low / (re-)entry high) II = Trade-off I = Flexicurity Low flexibility (low job mobility) III = Inflexicurity High flexibility (high job mobility) IV = Trade-off Low work security (exit high / (re-)entry low)

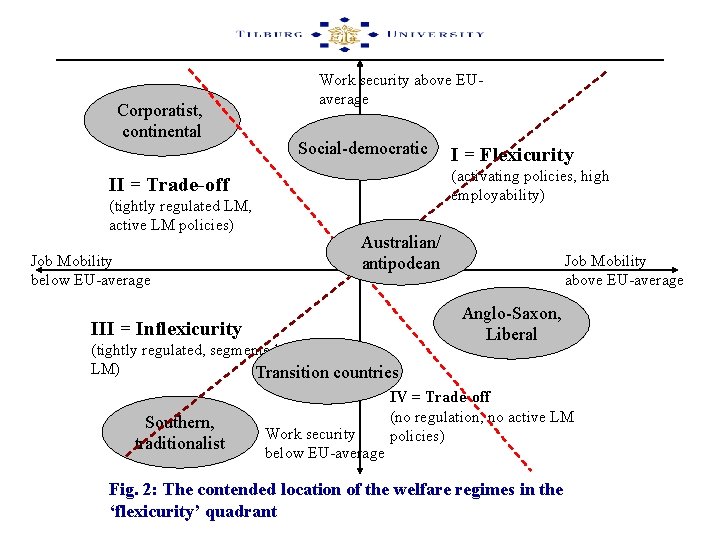

Corporatist, continental Work security above EUaverage Social-democratic (activating policies, high employability) II = Trade-off (tightly regulated LM, active LM policies) Job Mobility below EU-average Australian/ antipodean III = Inflexicurity (tightly regulated, segmented LM) Transition countries Southern, traditionalist I = Flexicurity Work security below EU-average Job Mobility above EU-average Anglo-Saxon, Liberal IV = Trade-off (no regulation, no active LM policies) Fig. 2: The contended location of the welfare regimes in the ‘flexicurity’ quadrant

![Measures using ECHP Job Mobility JM Occupational mobility JM based on occupational Measures using ECHP • Job Mobility (JM) – Occupational mobility [JM] (based on occupational](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/aa7ae0cc177a18622fda8eb1991cd660/image-10.jpg)

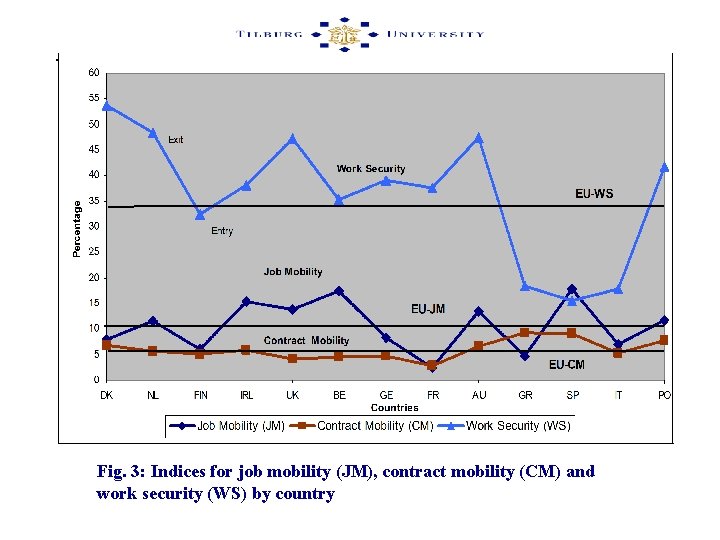

Measures using ECHP • Job Mobility (JM) – Occupational mobility [JM] (based on occupational class [EGP] : – Contract Mobility [CM] (mobility between employment contracts: flexible job; permanent job; self-employment) • Work Security (WS) – Staying in employment – Moving into more secure employment between t and t+1 for each of the pairs of years of observation Add: Income security; Working conditions

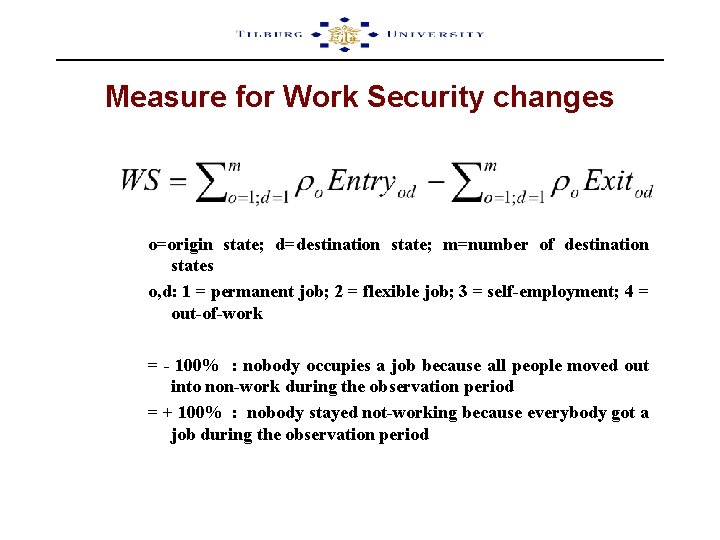

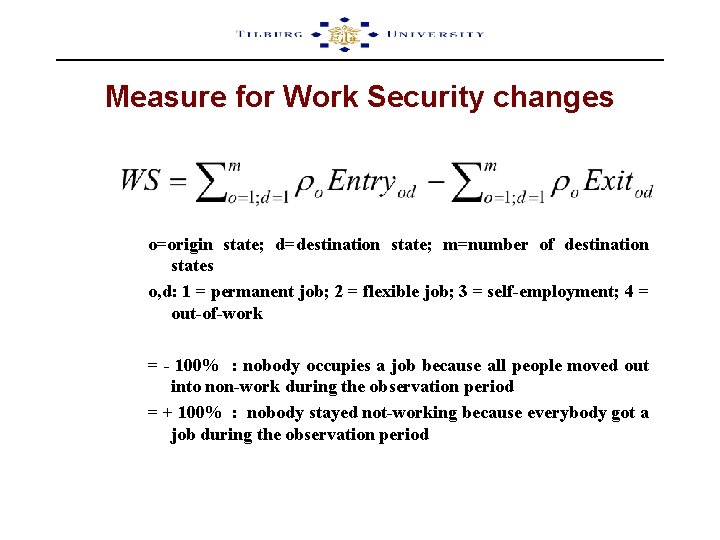

Ten ‘flexicurity’ indicators Flexibility • 1. Internal job-to-job mobility • 2. External job mobility • 3. Occupational class mobility • 4. Wage mobility (based on hourly real earnings) • 5. Contract mobility Work and income security • 6. Working time flexibility • 7. Labour market stability and mobility • 8. Job quality. Maintaining or moving into a better job • 9. Social protection related mobility • 10. Work-life balance related mobility (caring; educaton)

Measure for Work Security changes o=origin state; d=destination state; m=number of destination states o, d: 1 = permanent job; 2 = flexible job; 3 = self-employment; 4 = out-of-work = - 100% : nobody occupies a job because all people moved out into non-work during the observation period = + 100% : nobody stayed not-working because everybody got a job during the observation period

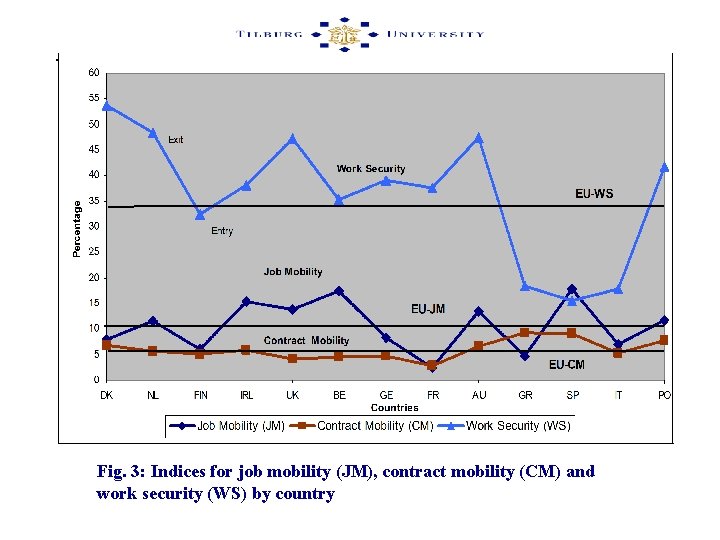

Fig. 3: Indices for job mobility (JM), contract mobility (CM) and work security (WS) by country

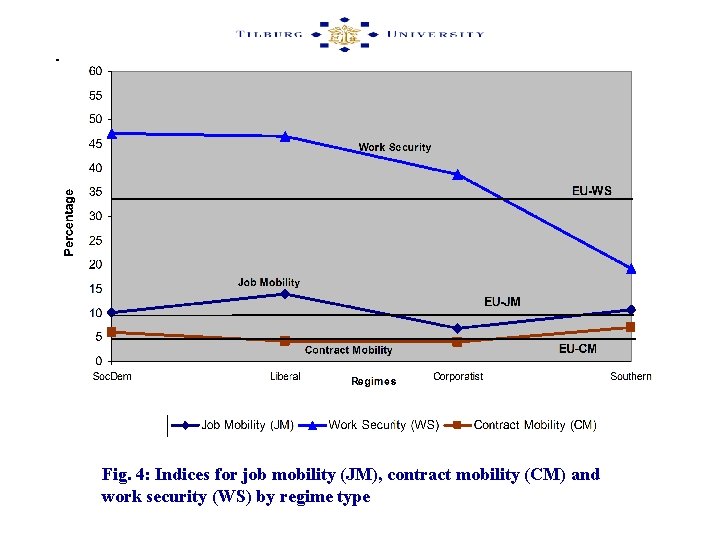

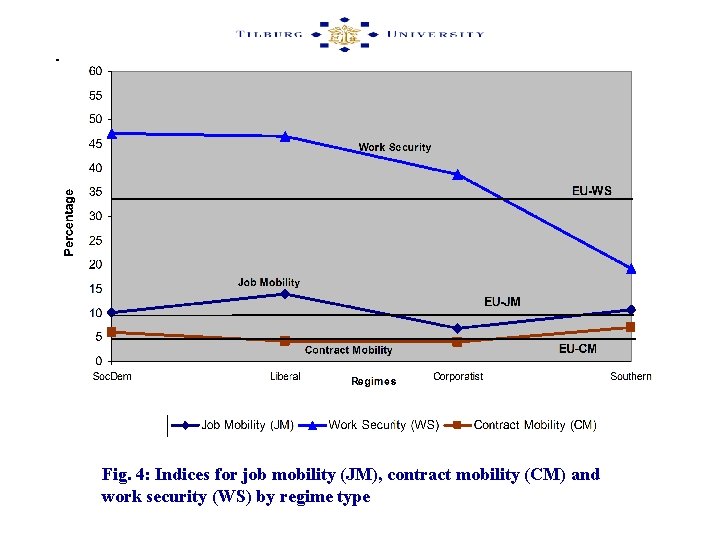

Fig. 4: Indices for job mobility (JM), contract mobility (CM) and work security (WS) by regime type

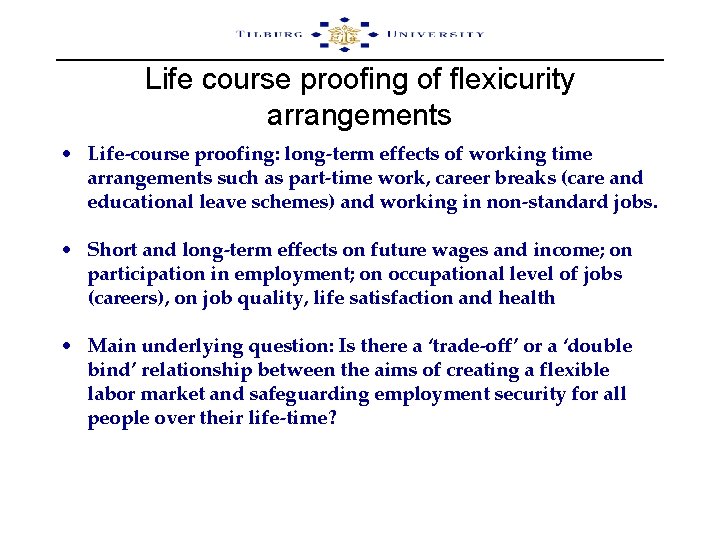

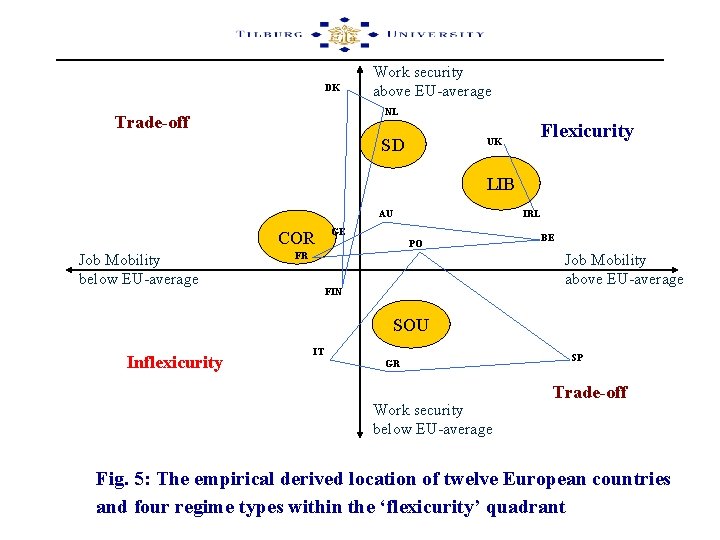

DK Work security above EU-average NL Trade-off SD Flexicurity UK LIB AU COR Job Mobility below EU-average IRL GE PO FR BE Job Mobility above EU-average FIN SOU Inflexicurity IT GR Work security below EU-average SP Trade-off Fig. 5: The empirical derived location of twelve European countries and four regime types within the ‘flexicurity’ quadrant

Conclusions and discussion • Define dynamic ‘outcome’ indicators for measuring the attained balance between flexibility and security • Define a broad set of dimensions of the ‘flexicurity’ concept like the ten dimensions proposed here • Shift the focus from short-term to long-term or life-course indicators and measure the effects of particular life course events on future careers (using panel and LC data) • Apply the measures on comparative data with a sufficient number of countries to find country clusters and to test whether policies matter and whether regimes change over time

Den danske model flexicurity

Den danske model flexicurity Conceptualization and measurement

Conceptualization and measurement Conceptualization, operationalization, and measurement

Conceptualization, operationalization, and measurement Cbt assessment and formulation

Cbt assessment and formulation Case conceptualization and treatment planning example

Case conceptualization and treatment planning example Construct in research

Construct in research Project conceptualization meaning

Project conceptualization meaning Project conceptualization

Project conceptualization Model conceptualization in simulation

Model conceptualization in simulation Customer needs identification

Customer needs identification Intensions

Intensions Structured conceptualization

Structured conceptualization Understanding and conceptualizing interaction

Understanding and conceptualizing interaction Humanistic approach case study

Humanistic approach case study Cbt basics

Cbt basics Operationalized independent variable

Operationalized independent variable Conceptualization def

Conceptualization def