CHILDRENS EXPERIENCES OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE REALITIES AND FANTASIES

![Culture and immigration as ‘reason’ for violence • Participant 2: [. . . ] Culture and immigration as ‘reason’ for violence • Participant 2: [. . . ]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/547fbced3a016ecb93b54244eb273b64/image-5.jpg)

- Slides: 23

CHILDREN’S EXPERIENCES OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE – REALITIES AND FANTASIES OF MIGRATION AND MOVEMENT Jane Callaghan, Joanne Alexander, Lisa Fellin, Judith Sixsmith, University of Northampton

Children’s experiences of domestic violence – resistance, resilience, agency • Most psychological and social science research on domestic violence focuses on its damaging effects on children – mental health, education, social skills, future relationships • A small body of work explores resilience – largely quantitative research, in terms of cognitive skills, emotional competence, and maternal role in buffering the negative impact of • A few small scale qualitative studies consider resilience and recovery • Only two studies explore use of space – Overlien and Wardaugh

UNARS • UNARS is the largest qualitative study of children’s experiences of domestic violence. • 110 interviews and photo elicitation activities with children in 4 European countries • UK interviews used spatial maps and family draw, Italian interviews included use of some drawings • Focus groups with professionals and carers • Policy analysis • A further 20 interviews with children following a therapeutic intervention

CULTURE AND CONTEXT AS AN EXPLANATORY FRAMEWORK FOR CHILDREN’S EXPERIENCES OF DOMESTIC VIOLENCE

![Culture and immigration as reason for violence Participant 2 Culture and immigration as ‘reason’ for violence • Participant 2: [. . . ]](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/547fbced3a016ecb93b54244eb273b64/image-5.jpg)

Culture and immigration as ‘reason’ for violence • Participant 2: [. . . ] it is also important to bear in mind the cultural and socioeconomical levels, as well as the immigration factor […] in lower classes the violence normally is physical, and in higher ones it is verbal, they are more sophisticated. Those behaviours are learnt [. . . ] (Spain – Professional focus group) • Conflations of poverty, migration, violence - the ‘immigration factor’. • culture as normalising violence • P 1: [. . . ] it seems to be what they’re used to, normal, so there’s lots of relearning to be done. (UK – Professional focus group 1) • P 3: the problem is the normalisation of the situation (Spain - Professional focus group)

• In Greece, a participant suggested that his culture of origin resulted in not getting the help and the protection he was needed. • Nikos: Many people could do something but they didn’t. . . …because we were from Albania and we would speak Albanian and my parents would be fighting over there ((eh)) others would say «((Eh)), these people are Albanian, and that’s how their culture is» they would think, ((eh)) «and, logically, that’s how they speak or that’s how they fight» . (Greece, Int: 11)

• Intervention less likely – “culture x is like that” • Isolation • Children suggested that neighbours were less likely to intervene because ‘culture x is like that’. There was also greater potential for social isolation for children who experience domestic violence and who come from migrant backgrounds. This is because they feel themselves to be doubly different, as both survivors of violence, and as migrant children.

Block to service seeking Ayisha: They’re (cultural issues) not picked up, it’s like most people don’t get it. I got married ‘cause I wanted my family ‘cause I wasn’t feeling well, but my family done me up. It wasn’t, it’s like, it wasn’t my mum’s fault what happened the day I got married, for three days I came back, I had a ((cries)) my back was ruined, everything was ruined. I didn’t go to the GP, I didn’t do nothing and my mum was just like “It’s normal”. I came back and there was no “Ayisha I love you” she was like “Go, go get a job and work” ((cries)). My mum’s never loved me, she’s always just wanted respect and d’you know what, I’m starting to hate my own culture because of that. (UK, Parent Focus Group 1)

Service access issues • Int: (. . . ) So you think services are particularly difficult to access (. . . ) • Ayisha: They’re difficult to access, and I’ve noticed that the workers that work here, they don’t, well, in my opinion, I don’t think they know much about forced marriages or anything, so I just sit there, I get on with whatever I’m doing, I drop my kids off, come back, cook, I go out. I don’t even bother coming in anymore ((to see Support Worker in office)) because I don’t think anyone can help me. And one, I’ve got a problem where I can’t ((erm)) open up (. . . ) communicate my feelings. I can with individuals in the flat, but I can’t do it with a professional ((cries)) so I, I, I, I’m never gonna get the help, ‘cause I can’t do it

Services ill equipped • “When the police arrived, the father convinced them that it was her who had been violent. She couldn’t speak much English, and couldn’t explain. So they took her away, and left the children with him. It took us six months of fighting, and a serious incident, to get the children back. ” (UK professional)

Migrant cultural identity as defiant positive George (interviewing his brother): if they came here, they’d just travelled from Brazil and came here and they said something really hurtful and really, really mean to you, what would you do to them? Say, “I am Paul, welcome to my country. Are you Chinese? ” If someone was being mean about your country, what would you say to them? Nothing. So you’d just let them be mean to your home country, that’s won football cups and are really good at football as well. Don’t care. What about you? I’d tell them to shut their little mouth. I’ll tell them to shut their little mouths. I’d tell them to piss off. I’d say that they’re gay.

Nostalgia, and fantasies of home • Natalia (Greece): But all this at home I don’t like ((. )) I mean, when we go to Albania there I have fun because there we don’t argue, we don’t ((. ))

DOMESTIC VIOLENCE AND INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT

• Movement, disruption and loss • Often underestimated – discourses of risk and safety v wellbeing

Nancy: The scary part of having police come into my house which means I’ve got a phobia of police now, I don’t like them, and then something happening in the middle, and then my dad being taken somewhere Int: Something happening in the middle [Nancy: Yeah], what was that? Nancy: I don’t know Int: You don’t remember that bit? Nancy: No. I just remember my dad being taken out of the house and taken off somewhere ((. )) for something Int: He was taken off somewhere, and then you moved to ((this county)) Nancy: Yeah, in the same night Int: ((surprised)) the same night? ! Nancy: So I didn’t get to say bye to any of my friends ((. )) so now I think they hate me, and I don’t think they remember me anymore Int: That sounds difficult that you had to move in the same night, what was it like for you? Nancy: Horrible, awkward, disturbing, ((. )) sad, ‘cause I lost loads, all of my, loads of my stuff, and my aminals Int: You left your animals as well? Nancy: ((umm)), they got sold Int: Did they? Nancy: I got Tyra still Int: Who’s Tyra Nancy: My doggie.

he’s made me lose on school work, ‘cause he’s made us move, move to somewhere ((looks at voice recorder)) ((smiles)) I’m not allowed to tell you where it is. But I’ve ((. )) it’s just been really hard and all I’ve been doing is since we’ve moved to this place, ((smiles)) I’m not allowed to tell you where about …. But I’ve ((. )) it’s just been really hard and all I’ve been doing is since we’ve moved to this place, ((smiles)) I’m not allowed to tell you where about, is just ((. )) is just boring ((. )) ‘cause all I do is sit down and watch TV and I, it gets boring and I feel like I should be at school instead of sitting down all day but doing nothing but watching TV (Ben, 8)

MIGRATION AND FANTASIES OF ESCAPE

• Violence occurs in material spaces • Control of space, control of bodies • Affective and embodied • Children’s management of abuse is not therefore always (or even mostly) verbal – they learn to cope by using the spaces around them, and their own bodies

My window on the world: Constraint and escape When it rained it was always a bad day. When the weather was good I went out with my good friends, we went around the city. Above all we went out to do graffiti. But when it rained I often stayed at home. Sometimes I passed my time by looking at the drawings made by rain drops on the window. I preferred to think about nothing. My father always stayed on the couch watching television. My mother, on the other hand, watched it into the kitchen. And when not watching television, they screamed. It was really better when they watched television. I could never watch it during the afternoon when they were there and so I looked at the window, it was like my personal TV. (Fabio, Italy) • The window as a space of potentiality – escape, and a world beyond here. • Rain as enabling a meditative state; also creative

Escapism: Outdoor Space and fantasies of flight In the drawing you can see two greek words: “I imagine” My imagination. I think various things. For example, to be up in the mountain with my friends, running, doing, playing. There are moments where I imagine ghosts too, for example like an adventure. “I dream” It’s like I’m flying. Somewhere, in another world. (Kostas, 14, Greece)

Getting away from it all – the fantasy of escape Here I’m fine. You know? And when I’m out of here I will be better Amaya, 17, Spain • Defiantly resilient self positioning • Associated image – open, outdoor spaces • Water, open sky – symbols of calm; also symbols of escape and freedom

Getting away from it all: the fantasy of escape Lally: If I leave, I’ll go abroad Int: Where does this thought come from? Lally: Because I do not like Italy. Int: You already know where to go? Lally: Either London or New York or Los Angeles (Lally, 16, Italy)

Spatiousness v constraint The sea, the sun, I like nature very much, I like the sun, very much. The light, I like very much this picture, to see the sun, the sea. And also there is this ship. The journey. (Natalia, 15, Greece)

Domestic and family violence protection act 2012

Domestic and family violence protection act 2012 Domestic and family violence protection act 2012

Domestic and family violence protection act 2012 Routine, universal screening for domestic violence means

Routine, universal screening for domestic violence means Common female sexual fantasies

Common female sexual fantasies Rape fantasies margaret atwood

Rape fantasies margaret atwood Florida coalition against domestic violence

Florida coalition against domestic violence The three r's for stopping domestic violence

The three r's for stopping domestic violence Domestic violence kink

Domestic violence kink Domestic violence in the hispanic community

Domestic violence in the hispanic community Virginia mandatory reporting law domestic violence

Virginia mandatory reporting law domestic violence National sovereignty and childrens day

National sovereignty and childrens day Moli texaschildrens

Moli texaschildrens Childrens christian fund

Childrens christian fund Childrens services

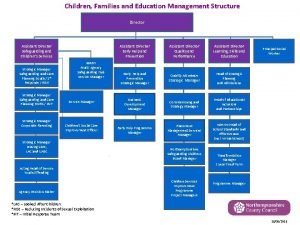

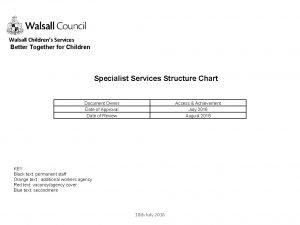

Childrens services Walsall childrens services

Walsall childrens services Levine childrens

Levine childrens Multi agency assessment

Multi agency assessment Traditional literature quiz

Traditional literature quiz The childrens university of manchester

The childrens university of manchester Childrens picture dictionary

Childrens picture dictionary Black childrens memorial

Black childrens memorial Fever in toddler

Fever in toddler History of childrens literature

History of childrens literature Colorado children's book award

Colorado children's book award