Officer Involved Domestic Violence 2012 Domestic Violence Generally

- Slides: 10

Officer Involved Domestic Violence 2012

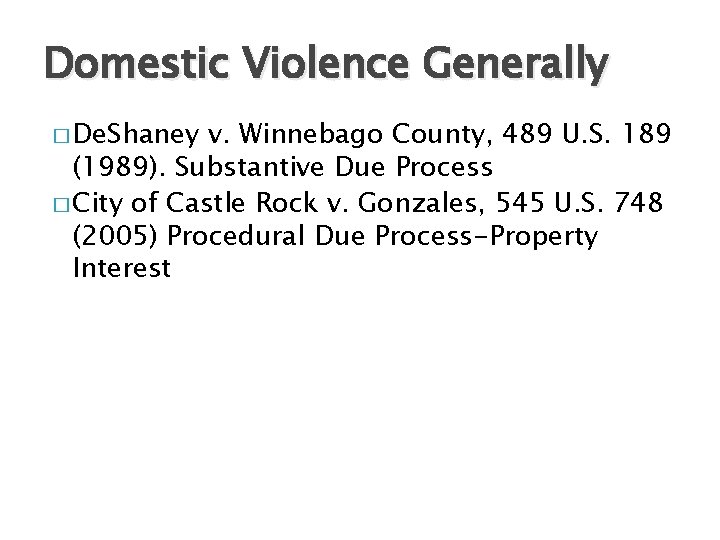

Domestic Violence Generally � De. Shaney v. Winnebago County, 489 U. S. 189 (1989). Substantive Due Process � City of Castle Rock v. Gonzales, 545 U. S. 748 (2005) Procedural Due Process-Property Interest

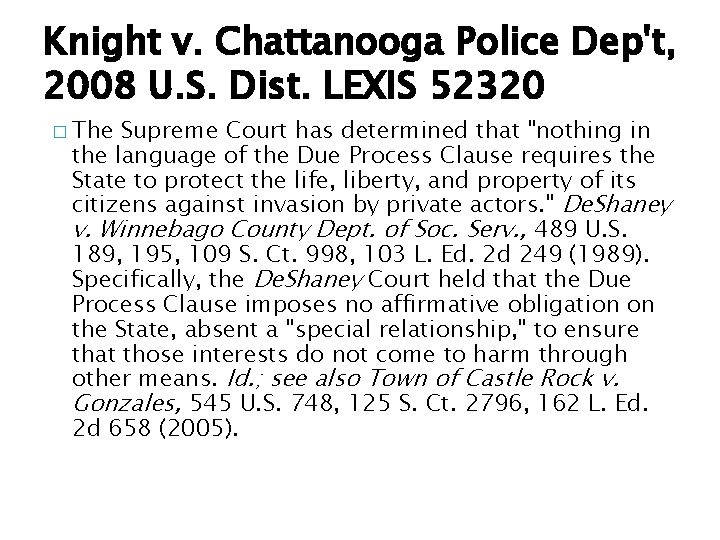

Knight v. Chattanooga Police Dep't, 2008 U. S. Dist. LEXIS 52320 � The Supreme Court has determined that "nothing in the language of the Due Process Clause requires the State to protect the life, liberty, and property of its citizens against invasion by private actors. " De. Shaney v. Winnebago County Dept. of Soc. Serv. , 489 U. S. 189, 195, 109 S. Ct. 998, 103 L. Ed. 2 d 249 (1989). Specifically, the De. Shaney Court held that the Due Process Clause imposes no affirmative obligation on the State, absent a "special relationship, " to ensure that those interests do not come to harm through other means. Id. ; see also Town of Castle Rock v. Gonzales, 545 U. S. 748, 125 S. Ct. 2796, 162 L. Ed. 2 d 658 (2005).

State Created Danger � Culp v. Rutledge, 343 Fed. Appx. 128 (6 th Cir. 2009) Need affirmative action to have state created danger…Sergeant told shooter’s exgirlfriend that shooter would be arrested but sergeant did not follow through on arrest.

Public Duty Doctrine � Affirmative Acts � Assurances of Safety � Special Relationship � Codified into Tort Claims Act

What about Law Enforcement Personnel? � Collateral Misconduct � 18 U. S. C. 922 (g) � United States v. Hayes, 555 U. S. 415 (2009).

Hayes � The definition of "misdemeanor crime of domestic violence" contained in 18 U. S. C. S. § 921(a)(33)(A) did not require the predicateoffense statute to include, as an element, the existence of the domestic relationship. Instead, it sufficed for the Government to charge and prove a prior conviction that was, in fact, for an offense committed against a spouse or other domestic victim. In other words look to the federal definition of domestic victim…if that applies…it does not matter what the elements of the state crime are as long as they would otherwise meet the federal definition.

Hayes Cont’d � 18 U. S. C. S. § 922(g)(9) makes it unlawful for any person who has been convicted in any court of a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence to possess in or affecting commerce any firearm or ammunition. 18 U. S. C. S. § 921(a)(33)(A) states that the term "misdemeanor crime of domestic violence" means an offense that (i) is a misdemeanor under federal, state, or tribal law and (ii) has, as an element, the use or attempted use of physical force, or the threatened use of a deadly weapon, committed by a current or former spouse, parent, or guardian of the victim, by a person with whom the victim shares a child in common, by a person who is cohabitating with or has cohabitated with the victim as a spouse, parent, or guardian, or by a person similarly situated to a spouse, parent, or guardian of the victim. Was underlying offense a misdemeanor? Was it committed by one of these federally identified parties? Was the crime one that has an element of use or attempted use of physical force or threatened use of a weapon…If so, elements of state crime irrelevant as long as it meets one of these elements.

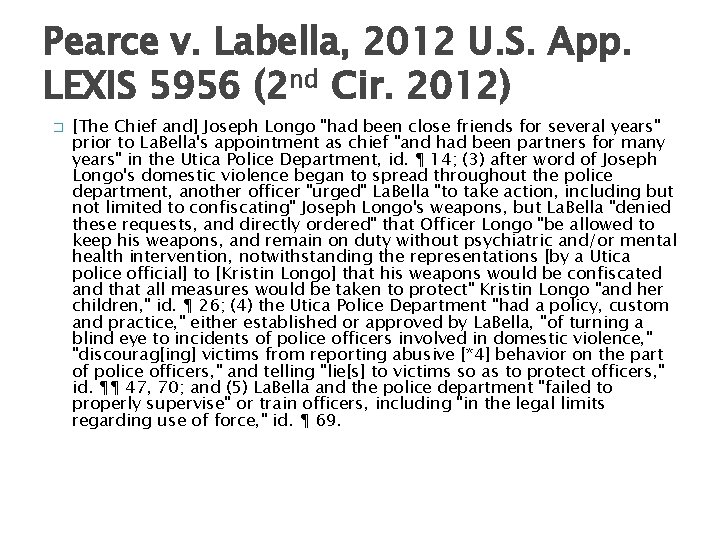

Pearce v. Labella, 2012 U. S. App. LEXIS 5956 (2 nd Cir. 2012) � [The Chief and] Joseph Longo "had been close friends for several years" prior to La. Bella's appointment as chief "and had been partners for many years" in the Utica Police Department, id. ¶ 14; (3) after word of Joseph Longo's domestic violence began to spread throughout the police department, another officer "urged" La. Bella "to take action, including but not limited to confiscating" Joseph Longo's weapons, but La. Bella "denied these requests, and directly ordered" that Officer Longo "be allowed to keep his weapons, and remain on duty without psychiatric and/or mental health intervention, notwithstanding the representations [by a Utica police official] to [Kristin Longo] that his weapons would be confiscated and that all measures would be taken to protect" Kristin Longo "and her children, " id. ¶ 26; (4) the Utica Police Department "had a policy, custom and practice, " either established or approved by La. Bella, "of turning a blind eye to incidents of police officers involved in domestic violence, " "discourag[ing] victims from reporting abusive [*4] behavior on the part of police officers, " and telling "lie[s] to victims so as to protect officers, " id. ¶¶ 47, 70; and (5) La. Bella and the police department "failed to properly supervise" or train officers, including "in the legal limits regarding use of force, " id. ¶ 69.

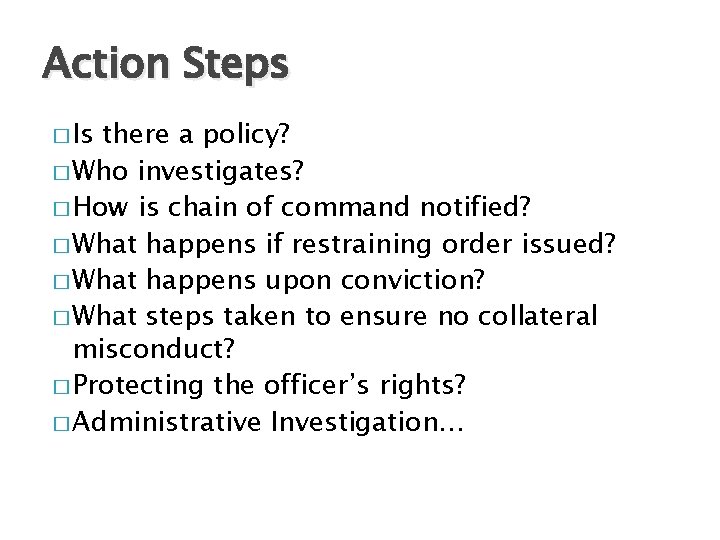

Action Steps � Is there a policy? � Who investigates? � How is chain of command notified? � What happens if restraining order issued? � What happens upon conviction? � What steps taken to ensure no collateral misconduct? � Protecting the officer’s rights? � Administrative Investigation…

Domestic and family violence protection act 2012

Domestic and family violence protection act 2012 Domestic and family violence protection act 2012

Domestic and family violence protection act 2012 A purposeful refusal to become generally involved

A purposeful refusal to become generally involved Florida coalition against domestic violence

Florida coalition against domestic violence Domestic violence in the hispanic community

Domestic violence in the hispanic community The three r's for stopping domestic violence

The three r's for stopping domestic violence Virginia mandatory reporting law domestic violence

Virginia mandatory reporting law domestic violence Domestic violence kink

Domestic violence kink Routine, universal screening for domestic violence means

Routine, universal screening for domestic violence means Types of retaling

Types of retaling Types of hospital admissions

Types of hospital admissions