www hoddereducation co ukgeographyreview Deindustrialisation Simon Oakes What

- Slides: 14

www. hoddereducation. co. uk/geographyreview Deindustrialisation Simon Oakes

What is deindustrialisation? • Deindustrialisation means a decline in the importance of industrial activity for a place. • More specifically it may refer to the falling percentage (or number) of a population who work in manufacturing, or the declining contribution of manufacturing activity to gross domestic product (GDP). • It involves a structural change in the way the economy of a place is organised. Structural changes in national economies are usually driven by a combination of internal and external factors, such as global shift or new technologies. • Deindustrialisation in the developed world dates back mainly to the 1960 s and 1970 s when global shift happened. This involved the movement of employment in manufacturing and services from economically developed to developing countries, mainly in Asia and Latin America. Hodder & Stoughton © 2018

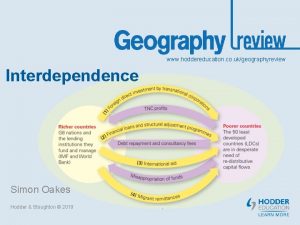

Global shift • Global shift stems from a combination of off-shoring, outsourcing and new business start-ups in emerging economies. • Global corporations based in developed countries have increased profits by shifting production to low-cost locations in Asia, South America and increasingly Africa. • Labour costs were cheap in China until recently. They remain very low in Bangladesh. Land prices and other business costs are also often lower in Asia than in Europe and North America. • Some developed-world manufacturing firms have been unable to compete with companies based in South Korea, China, India and other emerging economies. as a result, they have gone out of business. • Technological changes have made some industries obsolete. Hodder & Stoughton © 2018

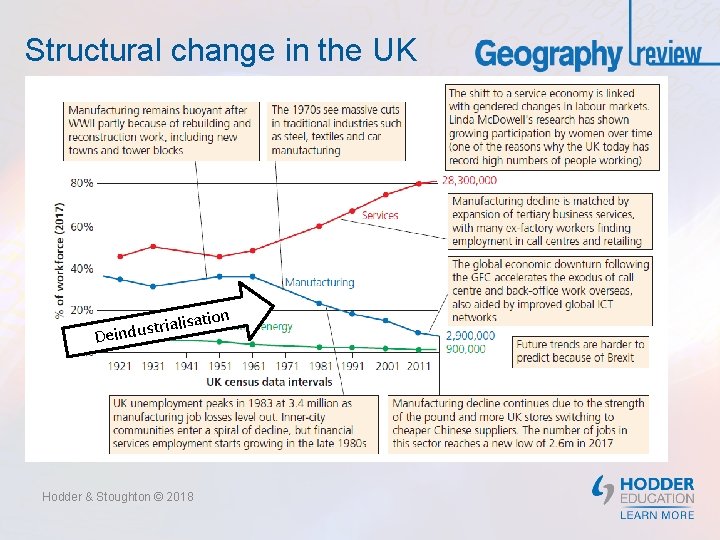

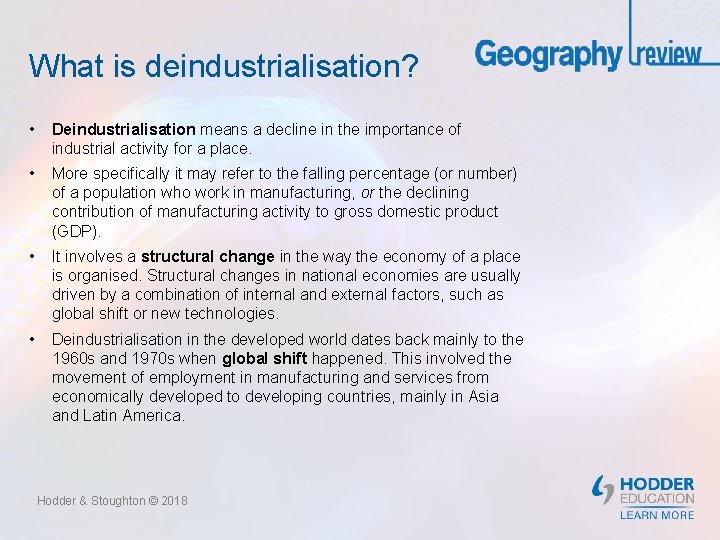

Structural change in the UK ation rialis t s u d n i De Hodder & Stoughton © 2018

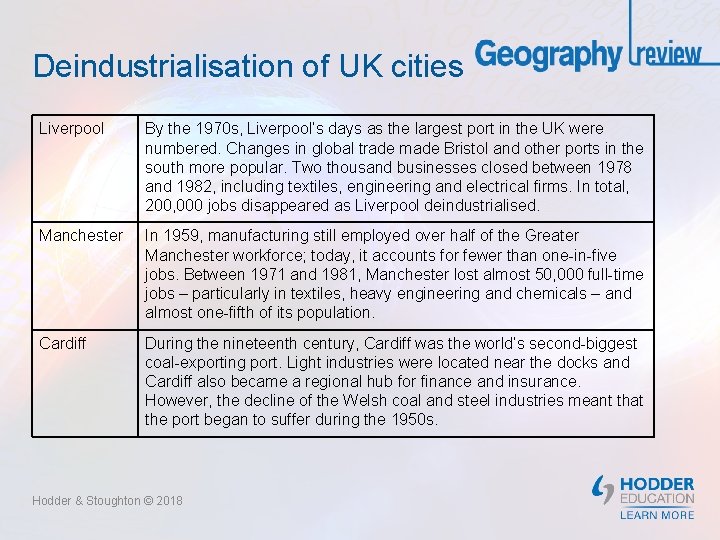

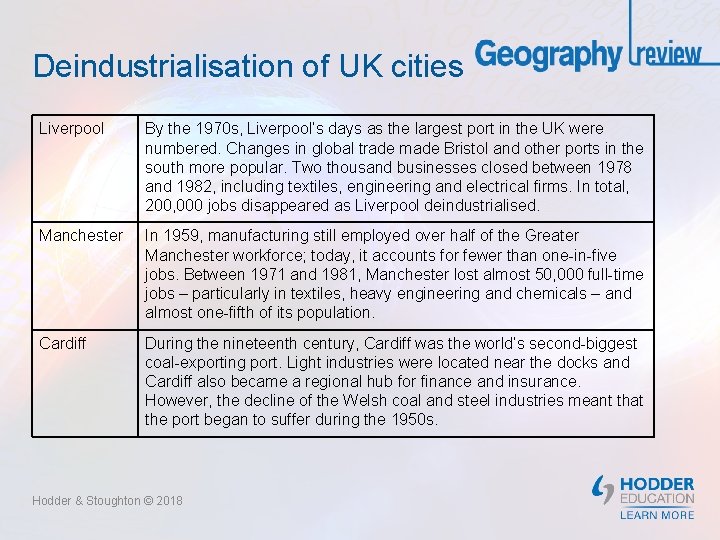

Deindustrialisation of UK cities Liverpool By the 1970 s, Liverpool’s days as the largest port in the UK were numbered. Changes in global trade made Bristol and other ports in the south more popular. Two thousand businesses closed between 1978 and 1982, including textiles, engineering and electrical firms. In total, 200, 000 jobs disappeared as Liverpool deindustrialised. Manchester In 1959, manufacturing still employed over half of the Greater Manchester workforce; today, it accounts for fewer than one-in-five jobs. Between 1971 and 1981, Manchester lost almost 50, 000 full-time jobs – particularly in textiles, heavy engineering and chemicals – and almost one-fifth of its population. Cardiff During the nineteenth century, Cardiff was the world’s second-biggest coal-exporting port. Light industries were located near the docks and Cardiff also became a regional hub for finance and insurance. However, the decline of the Welsh coal and steel industries meant that the port began to suffer during the 1950 s. Hodder & Stoughton © 2018

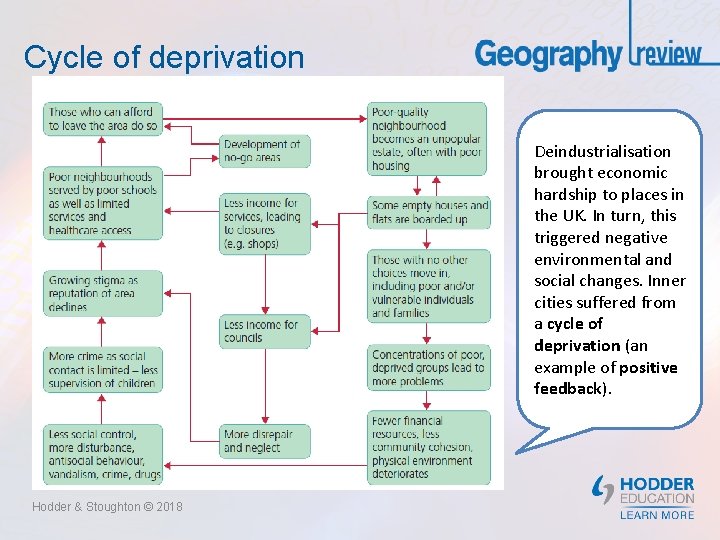

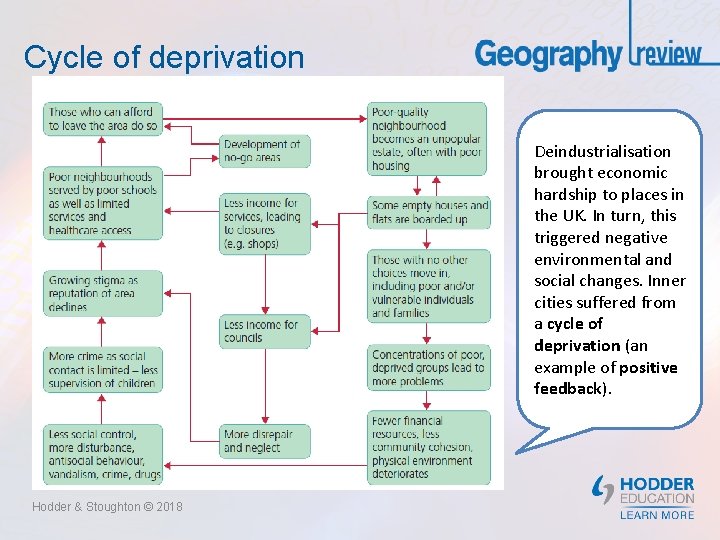

Cycle of deprivation Deindustrialisation brought economic hardship to places in the UK. In turn, this triggered negative environmental and social changes. Inner cities suffered from a cycle of deprivation (an example of positive feedback). Hodder & Stoughton © 2018

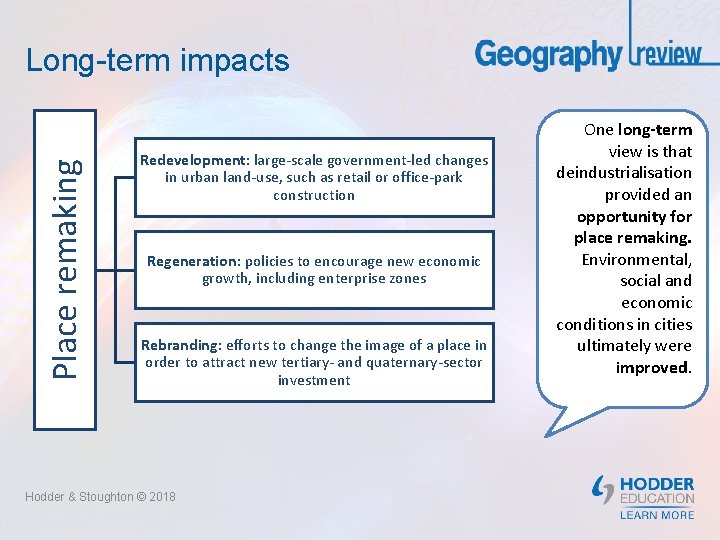

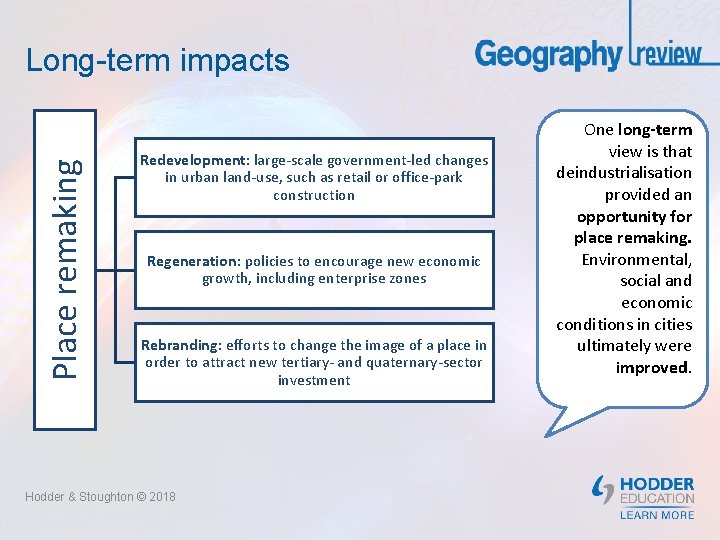

Place remaking Long-term impacts Redevelopment: large-scale government-led changes in urban land-use, such as retail or office-park construction Regeneration: policies to encourage new economic growth, including enterprise zones Rebranding: efforts to change the image of a place in order to attract new tertiary- and quaternary-sector investment Hodder & Stoughton © 2018 One long-term view is that deindustrialisation provided an opportunity for place remaking. Environmental, social and economic conditions in cities ultimately were improved.

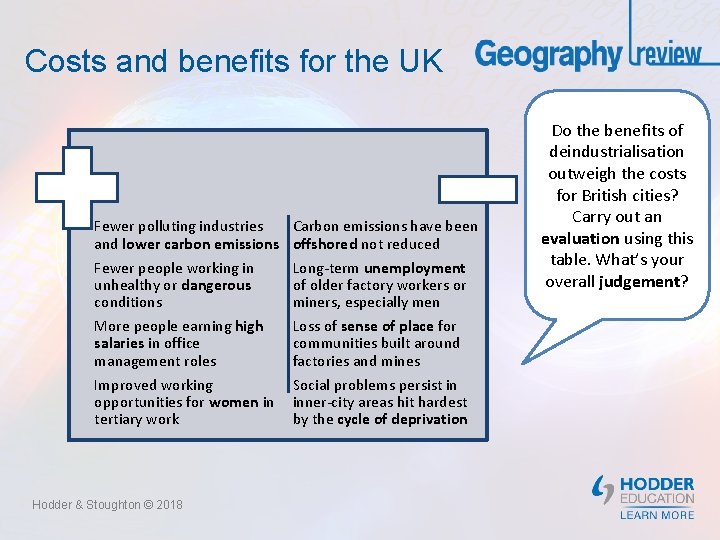

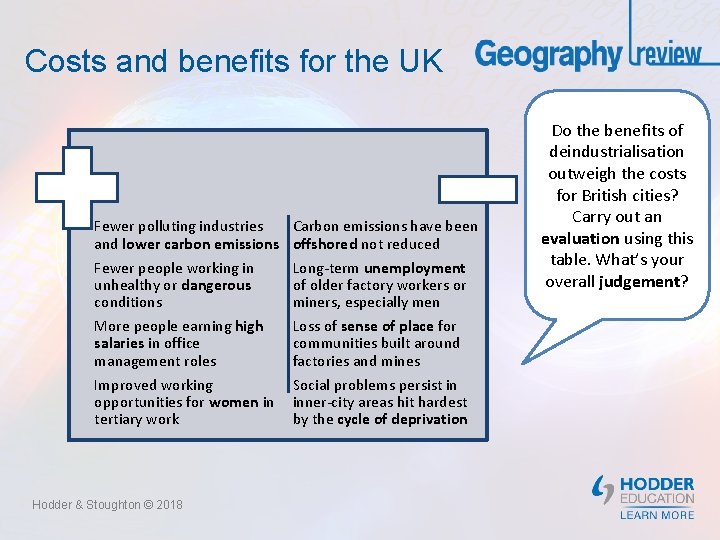

Costs and benefits for the UK Fewer polluting industries Carbon emissions have been and lower carbon emissions offshored not reduced Fewer people working in unhealthy or dangerous conditions More people earning high salaries in office management roles Improved working opportunities for women in tertiary work Hodder & Stoughton © 2018 Long-term unemployment of older factory workers or miners, especially men Loss of sense of place for communities built around factories and mines Social problems persist in inner-city areas hit hardest by the cycle of deprivation Do the benefits of deindustrialisation outweigh the costs for British cities? Carry out an evaluation using this table. What’s your overall judgement?

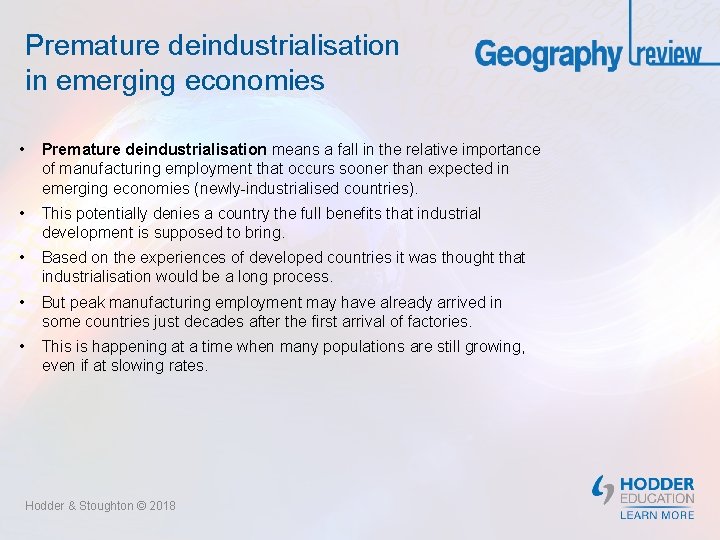

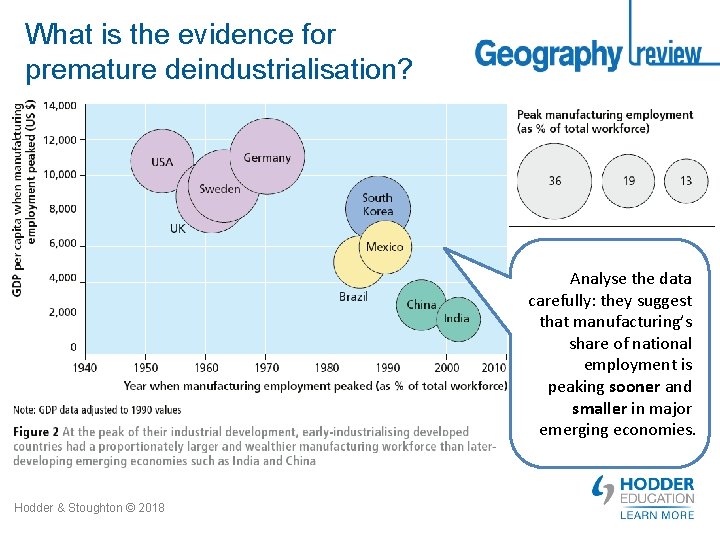

Premature deindustrialisation in emerging economies • Premature deindustrialisation means a fall in the relative importance of manufacturing employment that occurs sooner than expected in emerging economies (newly-industrialised countries). • This potentially denies a country the full benefits that industrial development is supposed to bring. • Based on the experiences of developed countries it was thought that industrialisation would be a long process. • But peak manufacturing employment may have already arrived in some countries just decades after the first arrival of factories. • This is happening at a time when many populations are still growing, even if at slowing rates. Hodder & Stoughton © 2018

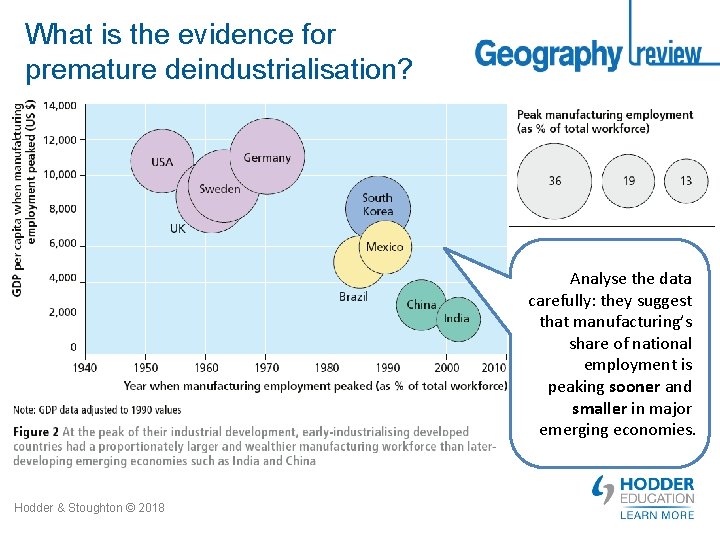

What is the evidence for premature deindustrialisation? Analyse the data carefully: they suggest that manufacturing’s share of national employment is peaking sooner and smaller in major emerging economies. Hodder & Stoughton © 2018

Why is premature deindustrialisation happening? • One argument is that advances in artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics are ‘chipping away’ at the numbers of workers needed in factories, even in countries where wages are low. • The rise of so called Sewbots is particularly worrying for Bangladesh where people work making textiles. The Sewbot, developed by Soft. Wear Automation, is a fully automated and intelligent sewing robot. • Taiwanese Electronics Group Foxconn, which makes Apple’s i. Phones, recently announced its aim to replace one-third of its workforce with robots. Much of its work is carried out in China where average hourly wages are now US$3. 60, meaning there are clear cost savings from adopting AI technology. • When Ford recently spent US$1 billion building a new factory in India, it installed state-of-the-art robotics and intends to keep human staffing at a minimum. Hodder & Stoughton © 2018

What are the implications of premature deindustrialisation? • The shorter gap between industrial ‘take off ’ (a phrase Rostow used) and peak industrialisation in emerging economies means that the increase in income per capita due to industrialisation has been lower. • This means fewer jobs becoming available than expected in some countries where until recently fertility was high. Political commentators believe instability and violence in the Middle East, including the rise of Daesh (ISIS), stems from high levels of youth unemployment. • Optimists, on the other hand, point out that if populations can be well educated it could mean that future generations are spared factory employment and can work in the tertiary sector (provided enough jobs are created). Hodder & Stoughton © 2018

Conclusions • Deindustrialisation brought challenges and opportunities to developedworld cities after the 1960 s and 1970 s. • Viewed positively, changes in global systems stimulated long-term placeremaking processes for UK inner cities. In general, economic conditions and the wellbeing of inner-city communities have improved over time. • New rounds of economic and technological change have started to threaten manufacturing employment in countries which only recently industrialised, such as Bangladesh. • The long-term implications of this are far from clear. Once again, structural changes driven by global systems are expected to bring challenges but also new opportunities. Hodder & Stoughton © 2018

This resource is part of GEOGRAPHY REVIEW, a magazine written for A-level students by subject experts. To subscribe to the full magazine go to: http: //www. hoddereducation. co. uk/geographyreview Simon Oakes is the author of two new books published by Hodder Education: Aiming for an A in A-level Geography and A-level Geography Topic Master: Changing Places. Background photo © 2015 Masoud Rezaeipoor/Adobe Stock Hodder & Stoughton © 2018