The Rhetoric of Exemplarity in Julius Caesar CASSIUS

- Slides: 22

The Rhetoric of Exemplarity in Julius Caesar

CASSIUS Tell me, good Brutus, can you see your face? BRUTUS No Cassius; for the eye sees not itself But by reflection, by some other things. CASSIUS ’Tis just, And it is very much lamented, Brutus, That you have no such mirrors as will turn Your hidden worthiness into your eye, That you might see your shadow: I have heard Where many of the best respect in Rome (Except immortal Caesar) speaking of Brutus. And groaning underneath the age’s yoke, Have wished that noble Brutus had his eyes. JC, 1. 2. 50 -62

A rarer spirit never Did steer humanity; but you gods will give us Some faults to make us men. Caesar is touched. AGRIPPA MECENUS When such a spacious mirror’s set before him, He needs must see himself. A & C, 5. 1. 31 -5

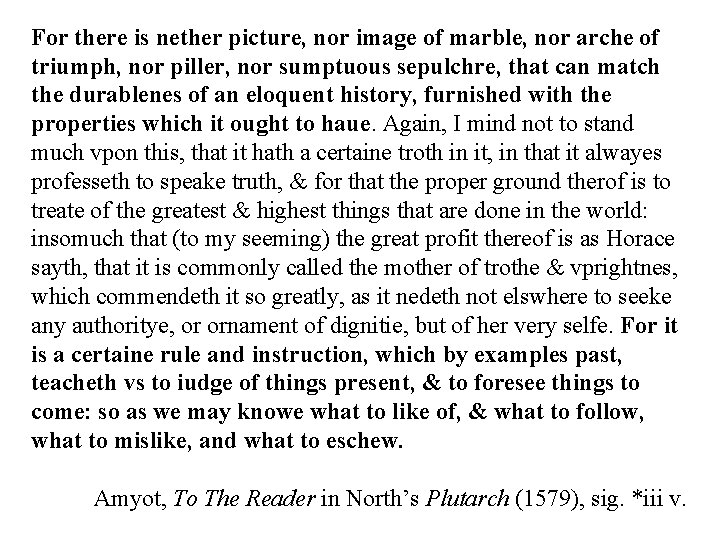

For there is nether picture, nor image of marble, nor arche of triumph, nor piller, nor sumptuous sepulchre, that can match the durablenes of an eloquent history, furnished with the properties which it ought to haue. Again, I mind not to stand much vpon this, that it hath a certaine troth in it, in that it alwayes professeth to speake truth, & for that the proper ground therof is to treate of the greatest & highest things that are done in the world: insomuch that (to my seeming) the great profit thereof is as Horace sayth, that it is commonly called the mother of trothe & vprightnes, which commendeth it so greatly, as it nedeth not elswhere to seeke any authoritye, or ornament of dignitie, but of her very selfe. For it is a certaine rule and instruction, which by examples past, teacheth vs to iudge of things present, & to foresee things to come: so as we may knowe what to like of, & what to follow, what to mislike, and what to eschew. Amyot, To The Reader in North’s Plutarch (1579), sig. *iii v.

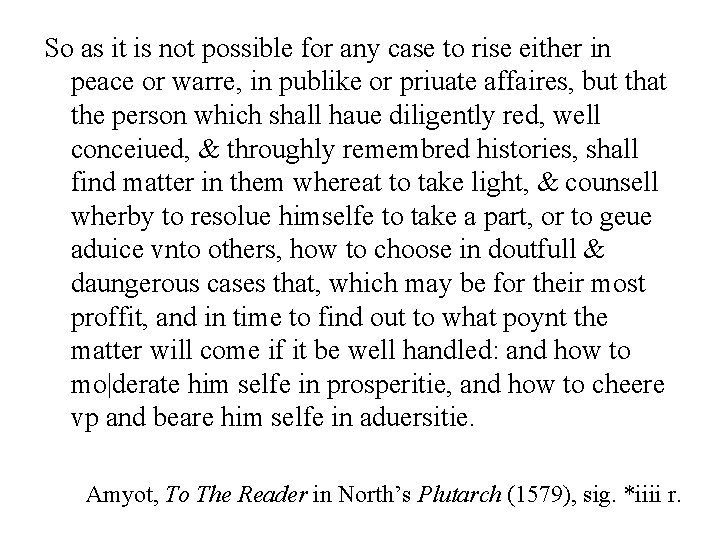

So as it is not possible for any case to rise either in peace or warre, in publike or priuate affaires, but that the person which shall haue diligently red, well conceiued, & throughly remembred histories, shall find matter in them whereat to take light, & counsell wherby to resolue himselfe to take a part, or to geue aduice vnto others, how to choose in doutfull & daungerous cases that, which may be for their most proffit, and in time to find out to what poynt the matter will come if it be well handled: and how to mo|derate him selfe in prosperitie, and how to cheere vp and beare him selfe in aduersitie. Amyot, To The Reader in North’s Plutarch (1579), sig. *iiii r.

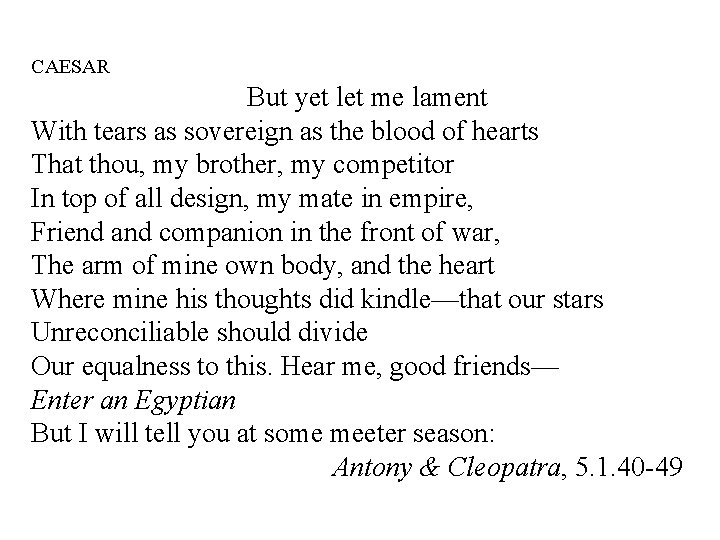

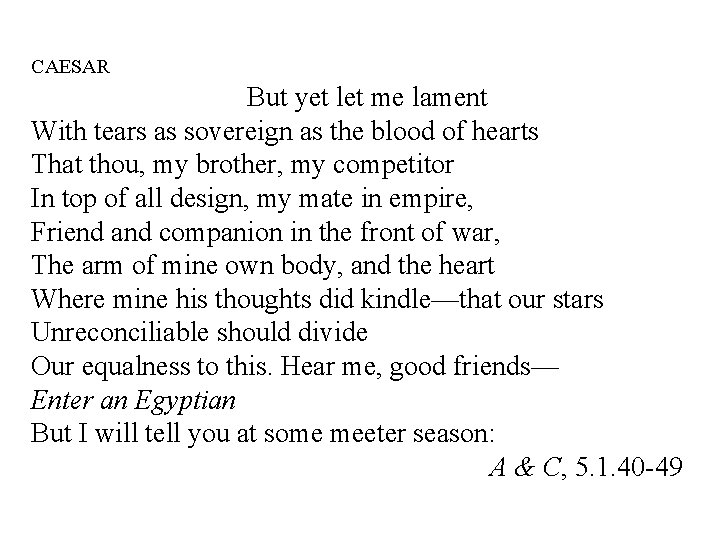

CAESAR But yet let me lament With tears as sovereign as the blood of hearts That thou, my brother, my competitor In top of all design, my mate in empire, Friend and companion in the front of war, The arm of mine own body, and the heart Where mine his thoughts did kindle—that our stars Unreconciliable should divide Our equalness to this. Hear me, good friends— Enter an Egyptian But I will tell you at some meeter season: Antony & Cleopatra, 5. 1. 40 -49

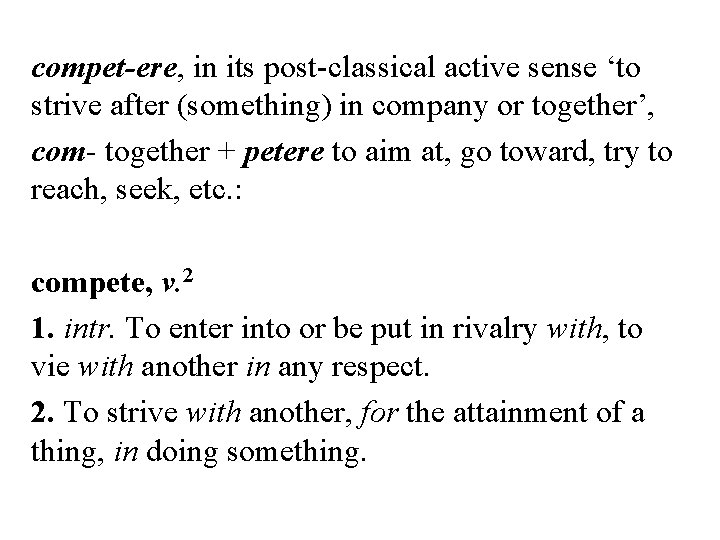

compet-ere, in its post-classical active sense ‘to strive after (something) in company or together’, com- together + petere to aim at, go toward, try to reach, seek, etc. : compete, v. 2 1. intr. To enter into or be put in rivalry with, to vie with another in any respect. 2. To strive with another, for the attainment of a thing, in doing something.

CAESAR But yet let me lament With tears as sovereign as the blood of hearts That thou, my brother, my competitor In top of all design, my mate in empire, Friend and companion in the front of war, The arm of mine own body, and the heart Where mine his thoughts did kindle—that our stars Unreconciliable should divide Our equalness to this. Hear me, good friends— Enter an Egyptian But I will tell you at some meeter season: A & C, 5. 1. 40 -49

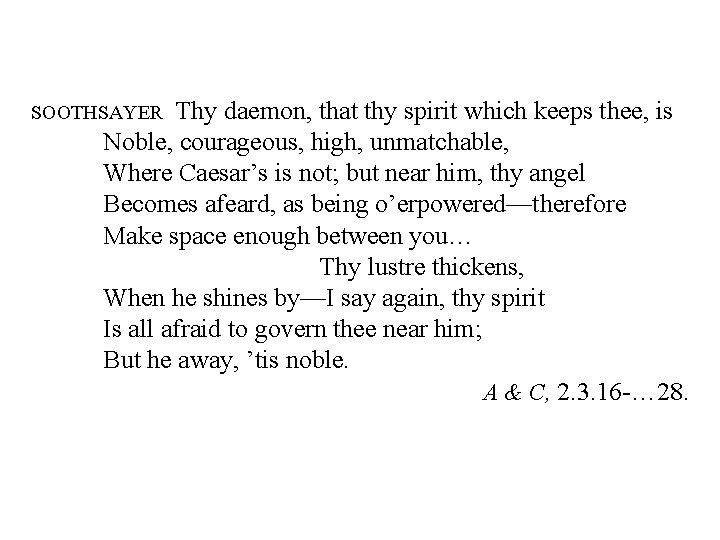

Thy daemon, that thy spirit which keeps thee, is Noble, courageous, high, unmatchable, Where Caesar’s is not; but near him, thy angel Becomes afeard, as being o’erpowered—therefore Make space enough between you… Thy lustre thickens, When he shines by—I say again, thy spirit Is all afraid to govern thee near him; But he away, ’tis noble. A & C, 2. 3. 16 -… 28. SOOTHSAYER

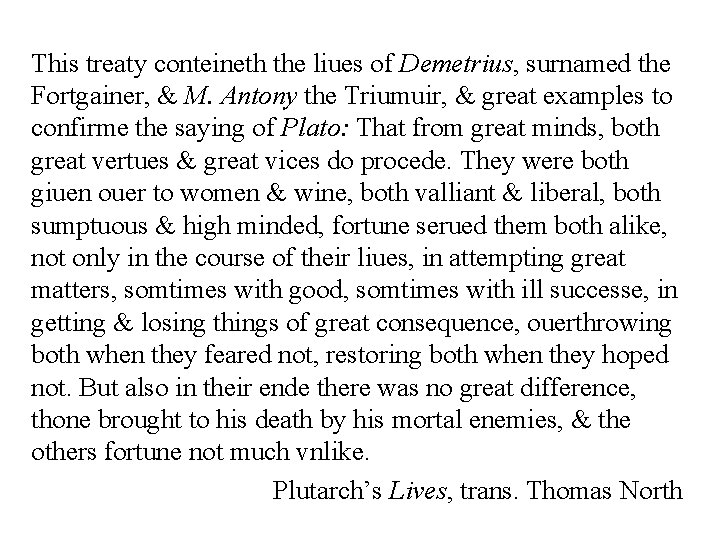

This treaty conteineth the liues of Demetrius, surnamed the Fortgainer, & M. Antony the Triumuir, & great examples to confirme the saying of Plato: That from great minds, both great vertues & great vices do procede. They were both giuen ouer to women & wine, both valliant & liberal, both sumptuous & high minded, fortune serued them both alike, not only in the course of their liues, in attempting great matters, somtimes with good, somtimes with ill successe, in getting & losing things of great consequence, ouerthrowing both when they feared not, restoring both when they hoped not. But also in their ende there was no great difference, thone brought to his death by his mortal enemies, & the others fortune not much vnlike. Plutarch’s Lives, trans. Thomas North

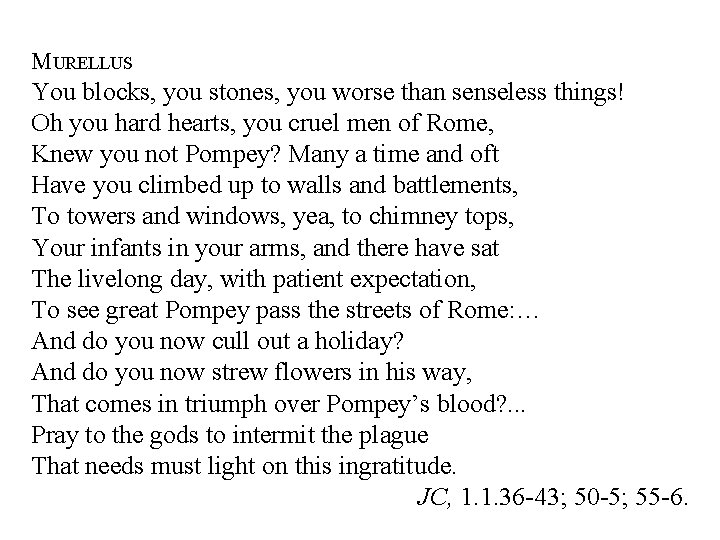

MURELLUS You blocks, you stones, you worse than senseless things! Oh you hard hearts, you cruel men of Rome, Knew you not Pompey? Many a time and oft Have you climbed up to walls and battlements, To towers and windows, yea, to chimney tops, Your infants in your arms, and there have sat The livelong day, with patient expectation, To see great Pompey pass the streets of Rome: … And do you now cull out a holiday? And do you now strew flowers in his way, That comes in triumph over Pompey’s blood? . . . Pray to the gods to intermit the plague That needs must light on this ingratitude. JC, 1. 1. 36 -43; 50 -5; 55 -6.

BRUTUS Into what dangers would you lead me, Cassius, That you would have me seek into myself For that which is not in me. CASSIUS Therefore, good Brutus, be prepared to hear. And since you know you cannot see yourself So well as by reflection, I your glass Will modestly discover to yourself That of yourself which you yet know not of. JC, 1. 2. 63 -70.

BRUTUS For let the gods so speed me as I love The name of honour more than I fear death. CASSIUS I know that virtue to be in you, Brutus, As well as I do know your outward favour. Well, honour is the subject of my story. I cannot tell what you and other men Think of this life: but for my single self I had as lief not be as live to be In awe of such a think as I myself. I was born as free as Caesar, so were you; We have both fed as well, and we can both Endure the winter’s cold as well as he. JC, 1. 2. 88 -99

Caesar said to me, ‘Dar’st thou, Cassius, now Leap in with me into this angry flood And swim to yonder point? ’ Upon the word, Accoutred as I was, I plunged in And bade him follow; so indeed he did. The torrent roared, and we did buffet it With lusty sinews, throwing it aside, And stemming it with hearts of controversy. But ere we could arrive the point proposed Caesar cried, ‘Help me, Cassius, or I sink!’ I, as Aeneas, our great ancestor Did from the flames of Troy upon his shoulder The old Anchises bear, so from the waves of Tiber Did I the tired Caesar: and this man Is now become a god, and Cassius is A wretched creature, and must bend his body If Caesar carelessly but nod on him. JC, 1. 2. 102 -118

‘Brutus’ and ‘Caesar’: what should be in that ‘Caesar’? Why should that name be sounded more than yours? Write them together: yours is as fair a name: Sound them, it doth become the mouth as well. Weigh them, it is as heavy; conjure with ’em, ‘Brutus’ will start as spirit as soon as ‘Caesar’. Now in the names of all the gods at once, Upon what meat doth this our Caesar feed That he is grown so great? Age, thou art shamed! Rome, thou hast lost the breed of noble bloods! When went there by an age, since the great flood, But it was famed with more than with one man. When could they say, till now, that talked of Rome, That her wide walks encompassed but one man? Now is it Rome indeed, and room enough, When there is in it but one only man. JC, 1. 2. 141 -56

You and I have heard our fathers say There was a Brutus once that would have brooked Th’eternal devil to keep his state in Rome As easily as a king. JC, 1. 2. 157 -60

CAESAR Would he were fatter! But I fear him not: Yet if my name were liable to fear I do not know that man I should avoid So soon as that spare Cassius. He reads much, He is a great observer, and he looks Quite through the deeds of men… Such men as he be never at their heart’s ease Whiles the behold a greater than themselves, And therefore are they very dangerous. I rather tell thee what is to be feared Than what I fear: for always I am Caesar. Come on my right hand, for this ear is deaf, And tell me truly what thou think’st of him. JC, 1. 2. 197 -

CAESAR I could be well moved if I were as you: If I could pray to move, prayers would move me. But I am constant as the northern star, Of whose true-fixed and resting quality There is no fellow in the firmament. The Skies are painted with unnumbered sparks: They are all fire, and every one doth shine; But there’s one in all doth hold his place. So in the world: ’tis furnished well with me, And men are flesh and blood, and apprehensive. Yet in the number I do know but one That unassailable holds on his rank Unshaked of motion. And that I am he Let me a little show it even in this, That I was constant Cimber should be banished And constant do remain to keep him so. JC, 3. 1. 58 -73.

O, pardon me, thou bleeding piece of earth, That I am meek and gentle with these butchers! Thou are the ruins of the noblest man That ever lived in the tide of times. ANTONY (Julius Caesar, 3. 1. 255 -8) BRUTUS Are yet two Romans living such as these? The last of all the Romans, fare thee well! It is impossible that ever Rome Should breed thy fellow. (Julius Caesar, 5. 3. 98 -101)

CASCA O he sits high in all the people’s hearts: And that which would appear offence in us His countenance, like richest alchemy, Will change to virtue and to worthiness. CASSIUS Him, and his worth, and our great need of him You have right well conceited. JC, 1. 2. 88 -99

ANTONY This was the noblest Roman of them all. All the conspirators save only he Did that they did in envy of great Caesar; He only in a general honest thought And common good to all make one of them. His life was gentle; and all the elements So mix’d in him that Nature might stand up And say to all the world ‘This was a man’. Julius Caesar, 5. 5. 68 -75

Does cassius die in julius caesar

Does cassius die in julius caesar Rhetorical devices in julius caesar act 3 scene 1

Rhetorical devices in julius caesar act 3 scene 1 Rhetorical devices in julius caesar

Rhetorical devices in julius caesar Have i played the part well then applaud me as i exit

Have i played the part well then applaud me as i exit Augustus caesar

Augustus caesar Why does caesar think cassius is dangerous

Why does caesar think cassius is dangerous Why does caesar distrust cassius?

Why does caesar distrust cassius? Webquest shakespeare

Webquest shakespeare Khubris

Khubris Caesar de bello gallico

Caesar de bello gallico English poet and playwright

English poet and playwright Caesar act

Caesar act Julius caesar final project ideas

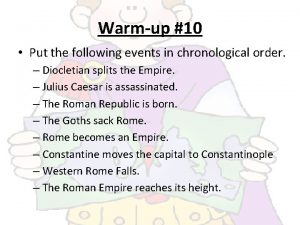

Julius caesar final project ideas Julius caesar chronological order

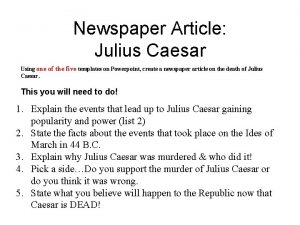

Julius caesar chronological order Julius caesar newspaper article

Julius caesar newspaper article Wherefore rejoice

Wherefore rejoice Caesar

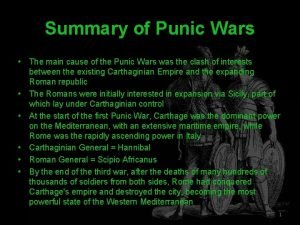

Caesar Punic wars summary

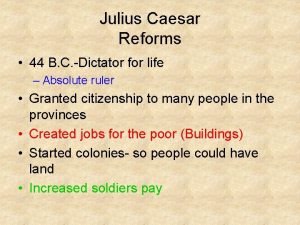

Punic wars summary Caesar reforms

Caesar reforms Julius caesar shmoop

Julius caesar shmoop Caesar intézkedései

Caesar intézkedései Julius caesar egyeduralma

Julius caesar egyeduralma Julius caesar act one

Julius caesar act one