SRCD 2019 March 22 2019 Seeing vs Seeing

- Slides: 1

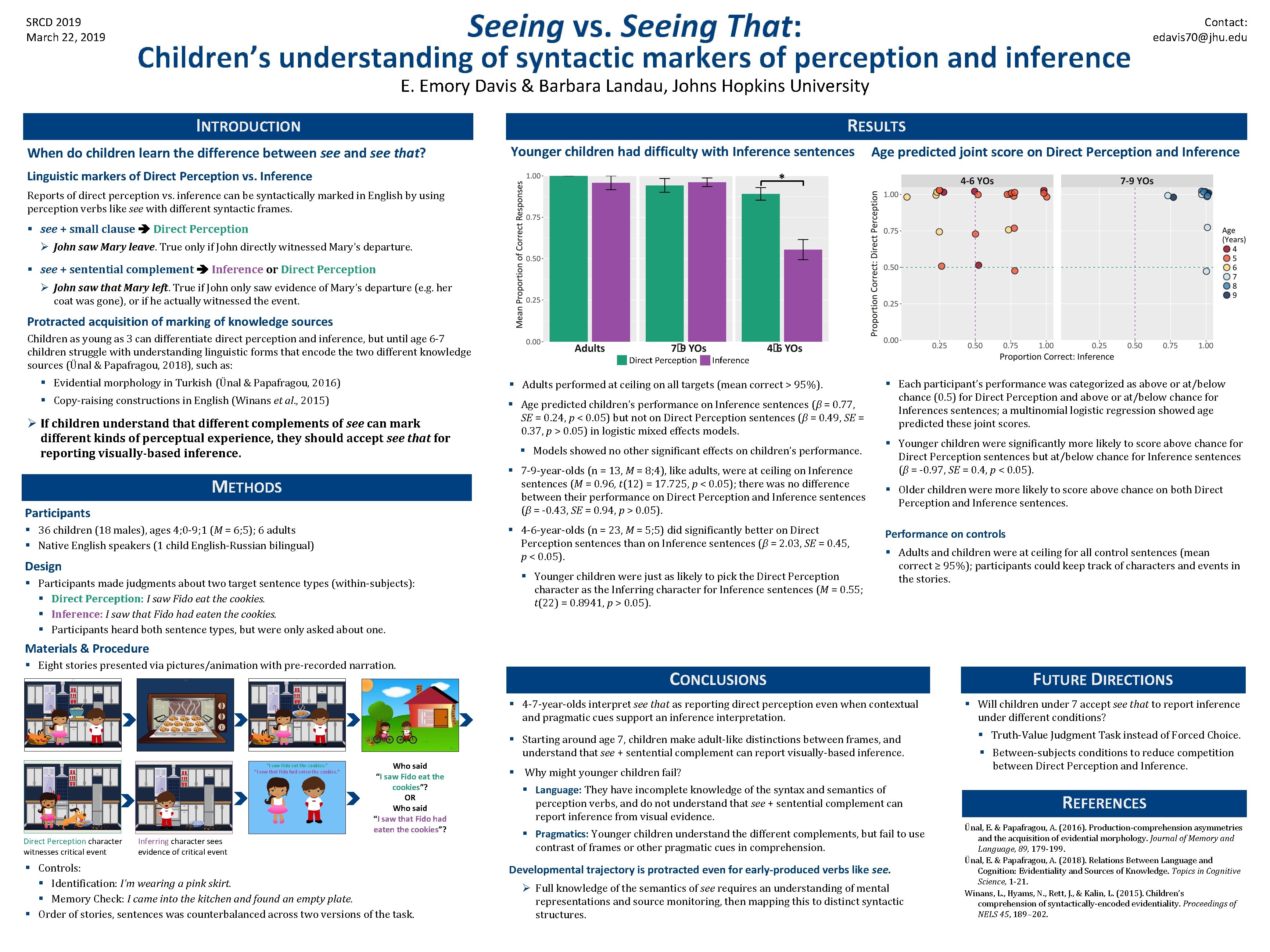

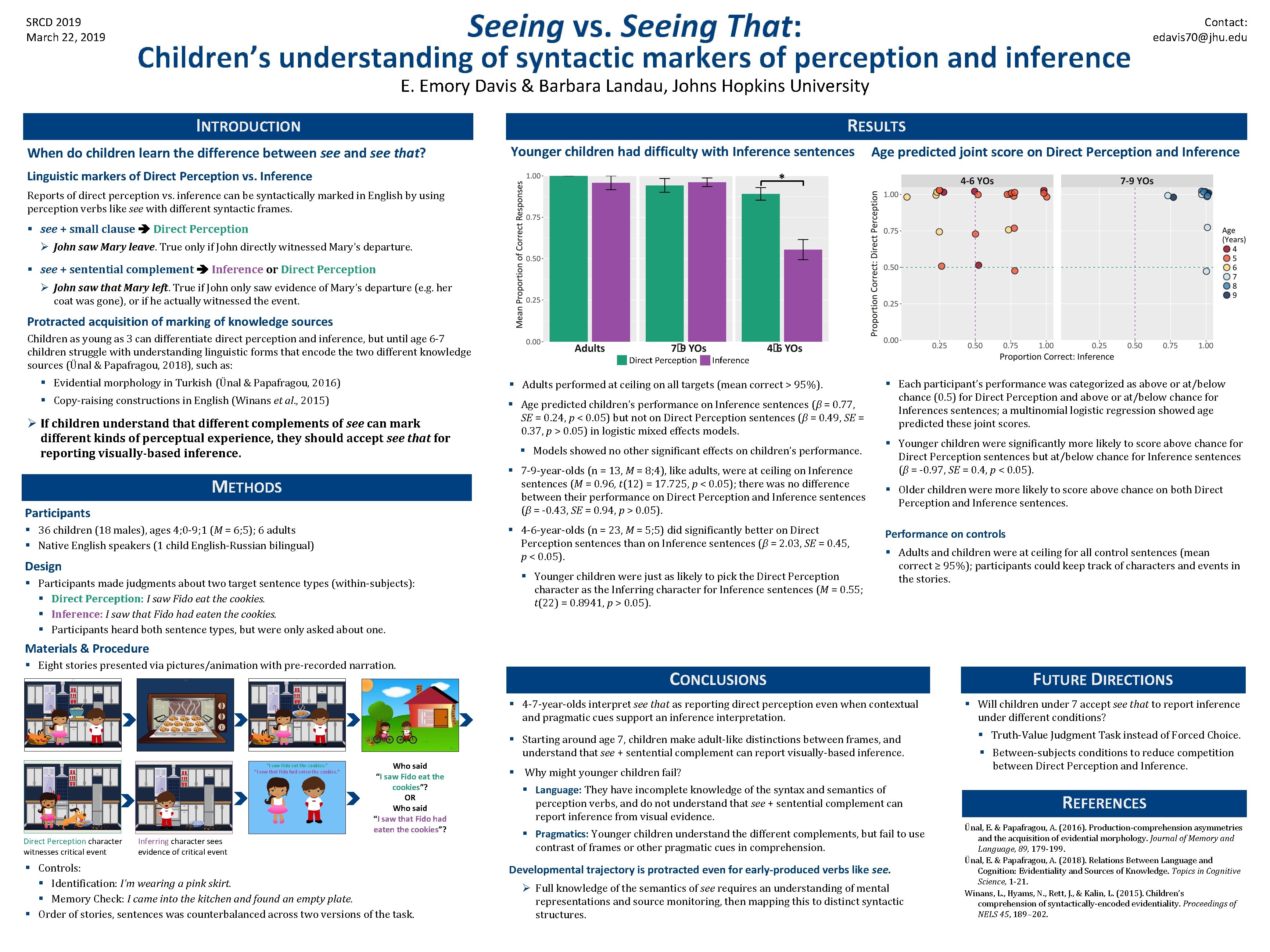

SRCD 2019 March 22, 2019 Seeing vs. Seeing That: Children’s understanding of syntactic markers of perception and inference Contact: edavis 70@jhu. edu E. Emory Davis & Barbara Landau, Johns Hopkins University RESULTS INTRODUCTION When do children learn the difference between see and see that? Younger children had difficulty with Inference sentences Linguistic markers of Direct Perception vs. Inference Age predicted joint score on Direct Perception and Inference * Reports of direct perception vs. inference can be syntactically marked in English by using perception verbs like see with different syntactic frames. § see + small clause Direct Perception Ø John saw Mary leave. True only if John directly witnessed Mary’s departure. § see + sentential complement Inference or Direct Perception Ø John saw that Mary left. True if John only saw evidence of Mary’s departure (e. g. her coat was gone), or if he actually witnessed the event. Protracted acquisition of marking of knowledge sources Children as young as 3 can differentiate direct perception and inference, but until age 6 -7 children struggle with understanding linguistic forms that encode the two different knowledge sources (Ünal & Papafragou, 2018), such as: Direct Perception Inference § Evidential morphology in Turkish (Ünal & Papafragou, 2016) § Adults performed at ceiling on all targets (mean correct > 95%). § Copy-raising constructions in English (Winans et al. , 2015) § Age predicted children’s performance on Inference sentences (β = 0. 77, SE = 0. 24, p < 0. 05) but not on Direct Perception sentences (β = 0. 49, SE = 0. 37, p > 0. 05) in logistic mixed effects models. Ø If children understand that different complements of see can mark different kinds of perceptual experience, they should accept see that for reporting visually-based inference. § Models showed no other significant effects on children’s performance. § 7 -9 -year-olds (n = 13, M = 8; 4), like adults, were at ceiling on Inference sentences (M = 0. 96, t(12) = 17. 725, p < 0. 05); there was no difference between their performance on Direct Perception and Inference sentences (β = -0. 43, SE = 0. 94, p > 0. 05). METHODS Participants § 36 children (18 males), ages 4; 0 -9; 1 (M = 6; 5); 6 adults § Native English speakers (1 child English-Russian bilingual) § 4 -6 -year-olds (n = 23, M = 5; 5) did significantly better on Direct Perception sentences than on Inference sentences (β = 2. 03, SE = 0. 45, p < 0. 05). Design § Participants made judgments about two target sentence types (within-subjects): § Direct Perception: I saw Fido eat the cookies. § Inference: I saw that Fido had eaten the cookies. § Participants heard both sentence types, but were only asked about one. § Younger children were just as likely to pick the Direct Perception character as the Inferring character for Inference sentences (M = 0. 55; t(22) = 0. 8941, p > 0. 05). § Each participant’s performance was categorized as above or at/below chance (0. 5) for Direct Perception and above or at/below chance for Inferences sentences; a multinomial logistic regression showed age predicted these joint scores. § Younger children were significantly more likely to score above chance for Direct Perception sentences but at/below chance for Inference sentences (β = -0. 97, SE = 0. 4, p < 0. 05). § Older children were more likely to score above chance on both Direct Perception and Inference sentences. Performance on controls § Adults and children were at ceiling for all control sentences (mean correct ≥ 95%); participants could keep track of characters and events in the stories. Materials & Procedure § Eight stories presented via pictures/animation with pre-recorded narration. CONCLUSIONS § 4 -7 -year-olds interpret see that as reporting direct perception even when contextual and pragmatic cues support an inference interpretation. § Starting around age 7, children make adult-like distinctions between frames, and understand that see + sentential complement can report visually-based inference. “I saw Fido eat the cookies. ” “I saw that Fido had eaten the cookies. ” Direct Perception character witnesses critical event Who said “I saw Fido eat the cookies”? OR Who said “I saw that Fido had eaten the cookies”? Inferring character sees evidence of critical event § Controls: § Identification: I’m wearing a pink skirt. § Memory Check: I came into the kitchen and found an empty plate. § Order of stories, sentences was counterbalanced across two versions of the task. § Why might younger children fail? § Language: They have incomplete knowledge of the syntax and semantics of perception verbs, and do not understand that see + sentential complement can report inference from visual evidence. § Pragmatics: Younger children understand the different complements, but fail to use contrast of frames or other pragmatic cues in comprehension. Developmental trajectory is protracted even for early-produced verbs like see. Ø Full knowledge of the semantics of see requires an understanding of mental representations and source monitoring, then mapping this to distinct syntactic structures. FUTURE DIRECTIONS § Will children under 7 accept see that to report inference under different conditions? § Truth-Value Judgment Task instead of Forced Choice. § Between-subjects conditions to reduce competition between Direct Perception and Inference. REFERENCES Ünal, E. & Papafragou, A. (2016). Production-comprehension asymmetries and the acquisition of evidential morphology. Journal of Memory and Language, 89, 179 -199. Ünal, E. & Papafragou, A. (2018). Relations Between Language and Cognition: Evidentiality and Sources of Knowledge. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1 -21. Winans, L. , Hyams, N. , Rett, J. , & Kalin, L. (2015). Children’s comprehension of syntactically-encoded evidentiality. Proceedings of NELS 45, 189– 202.