Sociocultural Psychology How your social context influences your

- Slides: 18

Sociocultural Psychology How your social context influences your behavior and thinking Participants, method, ethics? other useful resources: http: //www. spring. org. uk/2007/11/10 -piercing-insights-into-human -nature. php and http: //www. spring. org. uk/2010/01/10 -more-brilliant-social-psychology-studies. php and http: //www. youtube. com/playlist? list=PL 755 E 88 AC 2000 CC 6 A

The halo effect: Evidence for unconscious alteration of judgments. Nisbett, Richard E. ; Wilson, Timothy D. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 35(4), Apr 1977, 250 -256. doi: 10. 1037/0022 -3514. 35. 4. 250 Staged 2 different videotaped interviews with the same individual—a college instructor who spoke English with a European accent. In one of the interviews the instructor was warm and friendly, in the other, cold and distant. 118 undergraduates were asked to evaluate the instructor. Ss who saw the warm instructor rated his appearance, mannerisms, and accent as appealing, whereas those who saw the cold instructor rated these attributes as irritating. Results indicate that global evaluations of a person can induce altered evaluations of the person's attributes, even when there is sufficient information to allow for independent assessments of them. Furthermore, Ss were unaware of this influence of global evaluations on ratings of attributes. In fact, Ss who saw the cold instructor actually believed that the direction of influence was opposite to the true direction. They reported that their dislike of the instructor had no effect on their rating of his attributes but that their dislike of his attributes had lowered their global evaluations of him. (Psyc. INFO Database Record (c) 2012 APA, all rights reserved)

Fundamental Attribution Error • Lee et al. (1977) • Participants: students • Method: Participants randomly assigned to one of three roles (game show host, contestant on the game show, or member of the audience). Game show hosts asked to design their own questions. Upon the completion of the game show, the members of the audience were asked to rank the intelligence of both the host and the contestants. • Findings: Although the audience members knew that the host was randomly assigned to their position and had written the questions used for the show, the observers consistently ranked the game show host as being more intelligent than the contestants. Thus, they failed to attribute the persons performance to their role and instead attributed it to their perceived intelligence. Fundamental attribution error.

Individualistic and Collectivistic Attributional Styles • Morris & Peng (1994)- Interpretation of Murder—See book. • Kitayama and Peng—college students’ recordings (http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=Dfg. Qh 4 Ukdj. Q&list=PL 755 E 88 AC 2000 CC 6 A&i ndex=65) • Morris & Peng (1994) found from their fish behavior attribution experiment that more American than Chinese participants perceive the behavior (e. g. an individual fish swimming in front of a group of fish) as internally rather than externally caused. (http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=c. M 1 qfhyoc. Kw&list=PL 755 E 88 AC 2000 CC 6 A&i ndex=64)

Social perception and interpersonal behavior: On the self-fulfilling nature of social stereotypes. Snyder, Mark; Tanke, Elizabeth D. ; Berscheid, Ellen Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 35(9), Sep 1977, 656 -666. doi: 10. 1037/0022 -3514. 35. 9. 656 • • • Feeling the attraction To test this in the context of interpersonal attraction they had male students hold conversations with female students they'd just met through microphones and headsets. One of the quickest ways that people who've just met stereotype each other is by appearance. People automatically assume others who are more attractive are also more sociable, humorous, intelligent and so on. So to manipulate this, just before the conversation, along with biographical information about the person they were going to meet, the men were given a photograph. Half were shown a photograph of a woman who had been rated for attractiveness as an 8 out of 10 and half were given a photo of a woman rated as a 2 out of 10. Then the men talked to the women but without seeing them so they didn't know they weren't actually talking to the woman in the picture. Half expected to be talking to the attractive woman, half to the unattractive woman. The question is, would the women pick up on this fact and unconsciously fit into the stereotype they had been randomly assigned. By doing it this way the experimenters could rule out the influence of individual personalities and focus on the effect of expectations. When independent observers listened to the tapes of the conversation they found that when women were talking to men who thought they were very attractive, the women exhibited more of the behaviours stereotypically associated with attractive people: they talked more animatedly and seemed to be enjoying the chat more. What was happening was that the women conformed to the stereotype the men projected on them. So people really do sense how they are viewed by others and change their behaviour to match this expectation. Examined the self-fulfilling influences of social stereotypes on dyadic social interaction. Conceptual analysis suggests that a perceiver's actions based upon stereotype-generated attributions about a specific target individual may cause the behavior of that individual to confirm the perceiver's initially erroneous attributions. A paradigmatic investigation of the behavioral confirmation of stereotypes involving physical attractiveness (e. g. , "beautiful people are good people") is presented. 51 male "perceivers" interacted with 51 female "targets" (all undergraduates) whom they believed to be physically attractive or physically unattractive. Tape recordings of each participant's conversational behavior were analyzed by naive observer judges for evidence of behavioral confirmation. Results reveal that targets who were perceived (unknown to them) to be physically attractive came to behave in a friendly, likeable, and sociable manner in comparison with targets whose perceivers regarded them as unattractive. (42 ref) (Psyc. INFO Database Record (c) 2012 APA, all rights reserved)

Tajfel (1971) • social identity theory, social categorization, social comparison, (in-group, outgroup) • Population: Boys • Method: Boys randomly assigned to a group based on their supposed preference for the art of Kandinsky or Klee • • Findings: Each group (Kandinsky or Klee) were more likely to identify with the members of their own group willing to give higher awards to members of their own group Other group rated as less likeable, but never actually disliked group identity alone does not appear to be responsible for intergroup conflict In the absence of competition, social comparison does not necessarily produce a negative outcome • •

Cognitive Dissonance • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=kor. GK 0 y. G IDo&list=PL 755 E 88 AC 2000 CC 6 A&index=8

Stereotype Threat • Stereotype threat = when one is in a situation where there is a threat of being judged or treated stereotypically, or a fear of doing something that would inadvertently confirm that stereotype. • Who: Steele and Aronson • Participant Population: students--African American participants and European American participants • Method Design: Gave 30 -minute verbal test of difficult multiple-choice questions; one group was told it was a genuine test of their verbal abilities, the other presented same test as a laboratory task that was used to study how certain problems are generally solved. • Findings: In former group, African American students scored significantly lower than European Americans, in latter African Americans scored higher than the first group and test performance rose to match that of European Americans. Stereotype threat can affect the members of any social or cultural groups if members believe in stereotype, explains why some social groups believe they are more/less intelligent than others and shows beliefs can ham performance among these groups. Stereotype threat turns on spotlight anxiety, which causes emotional distress and pressure that may undermine performances (underperform and limit educational prospects. ) • Follow up/subsequent studies: mathematically gifted women scored lower on a difficult math test when told that the test tended to produce gender differences than when not told the test produced gender differences. http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=n. GEUVM 6 Qu. Mg&list=PL 755 E 88 AC 2000 CC 6 A&index=5 •

Robbers Cave Experiment Sherif (1961) • Conflict and prejudice • In this experiment twenty-two 11 year-old boys were taken to a summer camp in Robbers Cave State Park, Oklahoma, little knowing they were the subjects of an experiment. Before the trip the boys were randomly divided into two groups. It's these two groups that formed the basis of Sherif's study of how prejudice and conflict build up between two groups of people (Sherif et al. , 1961). • When the boys arrived, they were housed in separate cabins and, for the first week, did not know about the existence of the other group. They spent this time bonding with each other while swimming and hiking. Both groups chose a name which they had stencilled on their shirts and flags: one group was the Eagles and the other the Rattlers. (http: //www. spring. org. uk/2007/09/warpeace-and-role-of-power-in-sherifs. php) • http: //psychclassics. yorku. ca/Sherif/chap 7. htm

Asch Conformity Study • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=Ny. DDy. T 1 l Dh. A&list=PL 755 E 88 AC 2000 CC 6 A&index=12 • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=TYIh 4 Mkc f. JA&list=PL 755 E 88 AC 2000 CC 6 A&index=10

Milgram Obedience Shock Study • See book.

BYSTANDER INTERVENTION IN EMERGENCIES: DIFFUSION OF RESPONSIBILITY. By DARLEY, JOHN M. ; LATANE, BIBB Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 8(4, Pt. 1), Apr 1968, 377 -383. • • Abstract COLLEGE SS OVERHEARD AN EPILEPTIC SIEZURE. THEY BELIEVED EITHER THAT THEY ALONE HEARD THE EMERGENCY, OR THAT 1 OR 4 UNSEEN OTHERS WERE ALSO PRESENT. AS PREDICTED, THE PRESENCE OF OTHER BYSTANDERS REDUCED THE INDIVIDUAL'S FEELINGS OF PERSONAL RESPONSIBILITY AND LOWERED HIS SPEED OF REPORTING (P <. 01). IN GROUPS OF 3, MALES REPORTED NO FASTER THAN FEMALES, AND FEMALES REPORTED NO SLOWER WHEN THE 1 OTHER BYSTANDER WAS A MALE RATHER THAN A FEMALE. IN GENERAL, PERSONALITY AND BACKGROUND MEASURES WERE NOT PREDICTIVE OF HELPING. BYSTANDER INACTION IN REAL LIFE EMERGENCIES IS OFTEN EXPLAINED BY APATHY, ALIENATION, AND ANOMIE. RESULTS SUGGEST THAT THE EXPLANATION MAY LIE IN THE BYSTANDER'S RESPONSE TO OTHER OS THAN IN HIS INDIFFERENCE TO THE VICTIM. (Psyc. INFO Database Record (c) 2012 APA, all rights reserved) Another version: smoke-filled room http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=KE 5 Yw. N 4 NW 5 o&list=PL 755 E 88 AC 2000 CC 6 A&ind ex=41

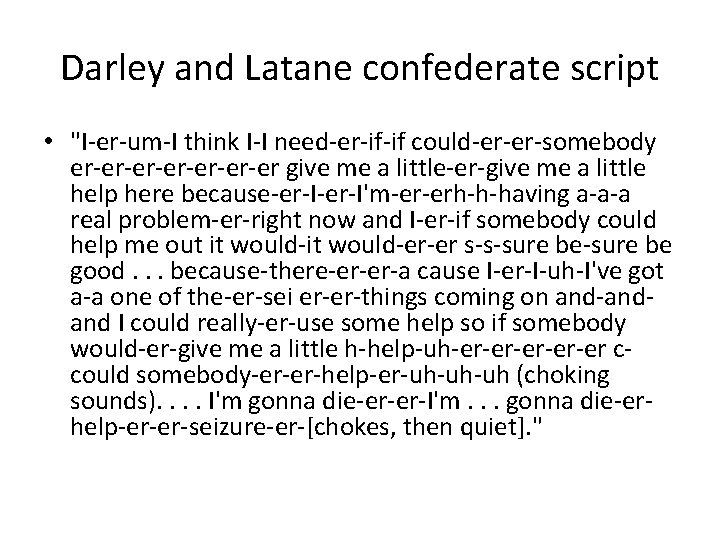

Darley and Latane confederate script • "I-er-um-I think I-I need-er-if-if could-er-er-somebody er-er-er-er give me a little-er-give me a little help here because-er-I'm-er-erh-h-having a-a-a real problem-er-right now and I-er-if somebody could help me out it would-er-er s-s-sure be good. . . because-there-er-er-a cause I-er-I-uh-I've got a-a one of the-er-sei er-er-things coming on and-andand I could really-er-use some help so if somebody would-er-give me a little h-help-uh-er-er-er ccould somebody-er-er-help-er-uh-uh-uh (choking sounds). . I'm gonna die-er-er-I'm. . . gonna die-erhelp-er-er-seizure-er-[chokes, then quiet]. "

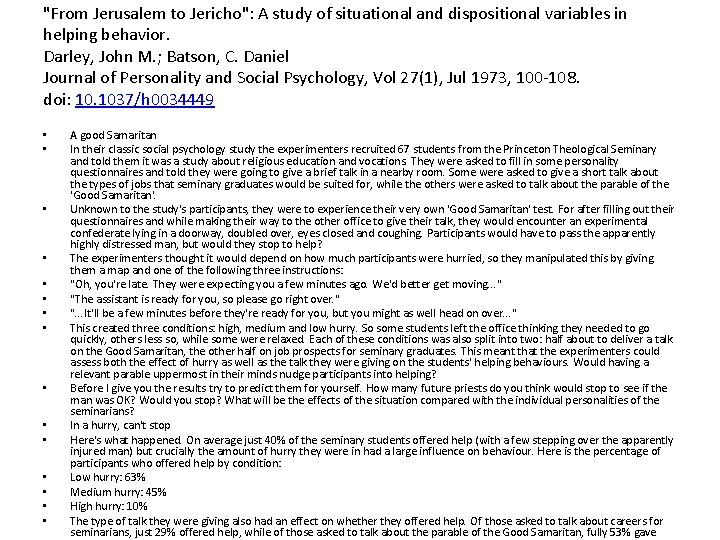

"From Jerusalem to Jericho": A study of situational and dispositional variables in helping behavior. Darley, John M. ; Batson, C. Daniel Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 27(1), Jul 1973, 100 -108. doi: 10. 1037/h 0034449 • • • • A good Samaritan In their classic social psychology study the experimenters recruited 67 students from the Princeton Theological Seminary and told them it was a study about religious education and vocations. They were asked to fill in some personality questionnaires and told they were going to give a brief talk in a nearby room. Some were asked to give a short talk about the types of jobs that seminary graduates would be suited for, while the others were asked to talk about the parable of the 'Good Samaritan'. Unknown to the study's participants, they were to experience their very own 'Good Samaritan' test. For after filling out their questionnaires and while making their way to the other office to give their talk, they would encounter an experimental confederate lying in a doorway, doubled over, eyes closed and coughing. Participants would have to pass the apparently highly distressed man, but would they stop to help? The experimenters thought it would depend on how much participants were hurried, so they manipulated this by giving them a map and one of the following three instructions: "Oh, you're late. They were expecting you a few minutes ago. We'd better get moving. . . " "The assistant is ready for you, so please go right over. " ". . . It'll be a few minutes before they're ready for you, but you might as well head on over. . . " This created three conditions: high, medium and low hurry. So some students left the office thinking they needed to go quickly, others less so, while some were relaxed. Each of these conditions was also split into two: half about to deliver a talk on the Good Samaritan, the other half on job prospects for seminary graduates. This meant that the experimenters could assess both the effect of hurry as well as the talk they were giving on the students' helping behaviours. Would having a relevant parable uppermost in their minds nudge participants into helping? Before I give you the results try to predict them for yourself. How many future priests do you think would stop to see if the man was OK? Would you stop? What will be the effects of the situation compared with the individual personalities of the seminarians? In a hurry, can't stop Here's what happened. On average just 40% of the seminary students offered help (with a few stepping over the apparently injured man) but crucially the amount of hurry they were in had a large influence on behaviour. Here is the percentage of participants who offered help by condition: Low hurry: 63% Medium hurry: 45% High hurry: 10% The type of talk they were giving also had an effect on whether they offered help. Of those asked to talk about careers for seminarians, just 29% offered help, while of those asked to talk about the parable of the Good Samaritan, fully 53% gave

Social Learning Theory/observational learning • Bandura’s Bobo doll study (1961) • Attention, retention, motor reproduction, motivation • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=h. HHdov. K HDNU • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=j. Wsxfo. JE w. QQ

The chameleon effect: The perception–behavior link and social interaction. By Chartrand, Tanya L. ; Bargh, John A. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 76(6), Jun 1999, 893 -910. • Abstract • The chameleon effect refers to nonconscious mimicry of the postures, mannerisms, facial expressions, and other behaviors of one's interaction partners, such that one's behavior passively and unintentionally changes to match that of others in one's current social environment. The authors suggest that the mechanism involved is the perception–behavior link, the recently documented finding (e. g. , J. A. Bargh, M. Chen, & L Burrows, 1996) that the mere perception of another's behavior automatically increases the likelihood of engaging in that behavior oneself. Experiment 1 showed that the motor behavior of participants unintentionally matched that of strangers with whom they worked on a task. Experiment 2 had confederates mimic the posture and movements of participants and showed that mimicry facilitates the smoothness of interactions and increases liking between interaction partners. Experiment 3 showed that dispositionally empathic individuals exhibit the chameleon effect to a greater extent than do other people. (Psyc. INFO Database Record (c) 2012 APA, all rights reserved)

Undermining children's intrinsic interest with extrinsic reward: A test of the "overjustification" hypothesis. Lepper, Mark R. ; Greene, David; Nisbett, Richard E. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Vol 28(1), Oct 1973, 129 -137. doi: 10. 1037/h 0035519 Conducted a field experiment with 3 -5 yr old nursery school children to test the "overjustification" hypothesis suggested by self-perception theory (i. e. , intrinsic interest in an activity may be decreased by inducing him to engage in that activity as an explicit means to some extrinsic goal). 51 Ss who showed intrinsic interest in a target activity during baseline observations were exposed to 1 of 3 conditions: in the expected-award condition, Ss agreed to engage in the target activity in order to obtain an extrinsic reward; in the unexpected-award condition, Ss had no knowledge of the reward until after they had finished with the activity; and in the no-award condition, Ss neither expected nor received the reward. Results support the prediction that Ss in the expected-award condition would show less subsequent intrinsic interest in the target activity than Ss in the other 2 conditions. (25 ref) (Psyc. INFO Database Record (c) 2012 APA, all rights reserved)

Compliance Techniques-Cialdini • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=c. Fd. Cz. N 7 R Ybw&list=PL 755 E 88 AC 2000 CC 6 A&index=53 • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=ZF 1 p. Vqk. G TO 4&list=PL 755 E 88 AC 2000 CC 6 A&index=54 • http: //www. youtube. com/watch? v=d. CTNLek GA 5 I&list=PL 755 E 88 AC 2000 CC 6 A&index=55

Exploring lifespan development chapter 1

Exploring lifespan development chapter 1 Socio-cultural context example

Socio-cultural context example What is literary context

What is literary context Little emphasis on sociocultural context

Little emphasis on sociocultural context Social psychology class

Social psychology class To a social psychologist a perceived incompatibility

To a social psychologist a perceived incompatibility Social psychology ap psychology

Social psychology ap psychology Social psychology is the scientific study of

Social psychology is the scientific study of Social influences on consumer behavior

Social influences on consumer behavior Examples of social influences

Examples of social influences Chapter 1 lesson 2 what affects your health

Chapter 1 lesson 2 what affects your health Social thinking and social influence in psychology

Social thinking and social influence in psychology Social thinking adalah

Social thinking adalah High context vs low context culture ppt

High context vs low context culture ppt High context vs low context culture ppt

High context vs low context culture ppt Presupposition examples sentences

Presupposition examples sentences Verbal adalah

Verbal adalah Social thinking social influence social relations

Social thinking social influence social relations Memory storage is never automatic; it always takes effort

Memory storage is never automatic; it always takes effort