RESEARCH QUESTIONS LOUIS COHEN LAWRENCE MANION AND KEITH

- Slides: 19

RESEARCH QUESTIONS © LOUIS COHEN, LAWRENCE MANION AND KEITH MORRISON © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

STRUCTURE OF THE CHAPTER • • • Why have research questions? Where do research questions come from? What kinds of research question are there? Devising your research question(s) Making your research question answerable How many research questions should I have? © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

WHAT ARE RESEARCH QUESTIONS? ‘They are the concrete questions, carefully composed in order to address the research objectives, to constitute a fair operationalization and embodiment of a valid set of indicators for addressing the research objectives, providing answers which address the research purposes with warranted data. ’ © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

WHY HAVE RESEARCH QUESTIONS? • • • They frame the research They get to the heart of the research issue They give direction to the research They indicate what the research is about They render the research practicable (able to be conducted) © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

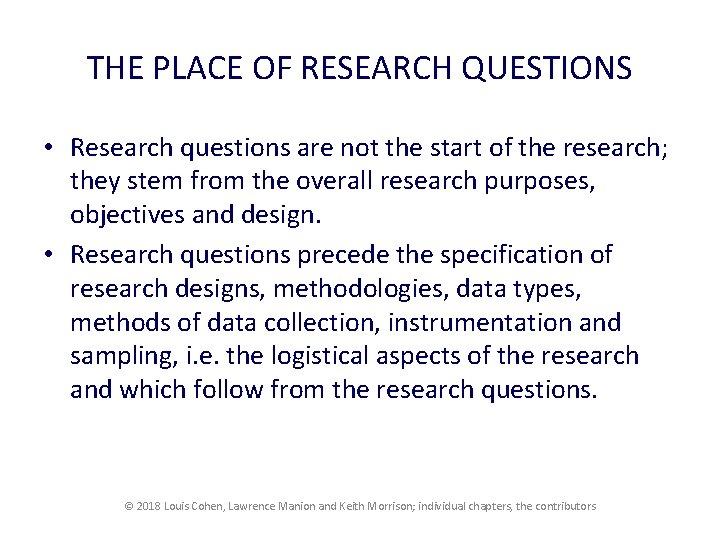

THE PLACE OF RESEARCH QUESTIONS • Research questions are not the start of the research; they stem from the overall research purposes, objectives and design. • Research questions precede the specification of research designs, methodologies, data types, methods of data collection, instrumentation and sampling, i. e. the logistical aspects of the research and which follow from the research questions. © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

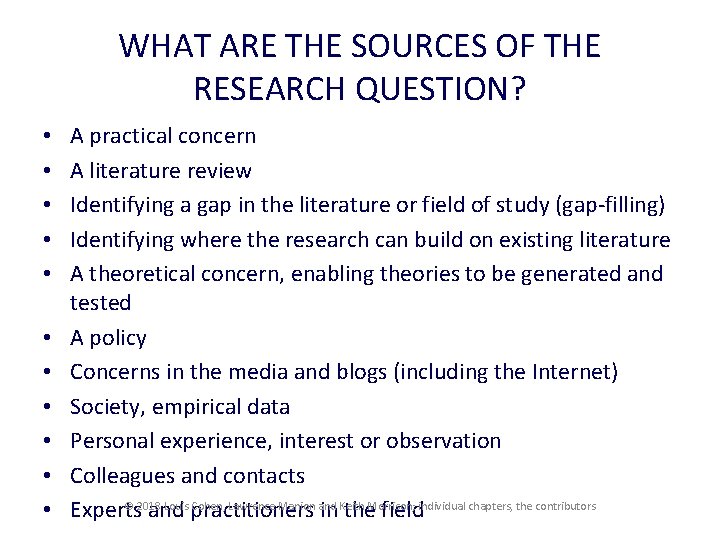

WHAT ARE THE SOURCES OF THE RESEARCH QUESTION? • • • A practical concern A literature review Identifying a gap in the literature or field of study (gap-filling) Identifying where the research can build on existing literature A theoretical concern, enabling theories to be generated and tested A policy Concerns in the media and blogs (including the Internet) Society, empirical data Personal experience, interest or observation Colleagues and contacts © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors Experts and practitioners in the field

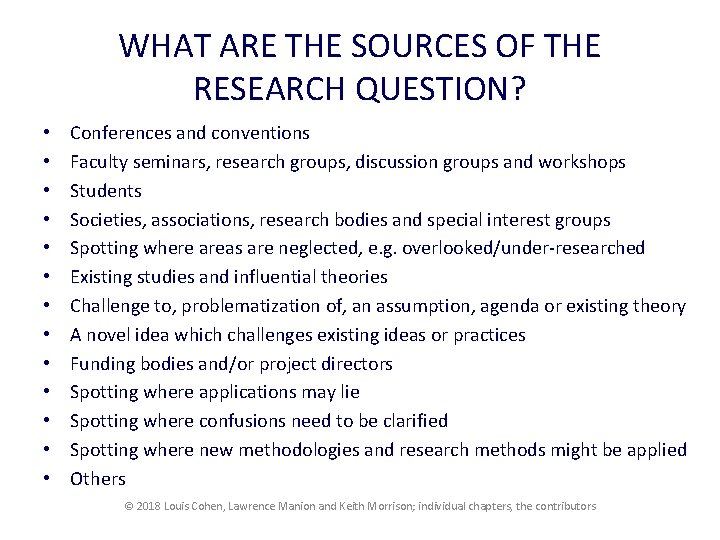

WHAT ARE THE SOURCES OF THE RESEARCH QUESTION? • • • • Conferences and conventions Faculty seminars, research groups, discussion groups and workshops Students Societies, associations, research bodies and special interest groups Spotting where areas are neglected, e. g. overlooked/under-researched Existing studies and influential theories Challenge to, problematization of, an assumption, agenda or existing theory A novel idea which challenges existing ideas or practices Funding bodies and/or project directors Spotting where applications may lie Spotting where confusions need to be clarified Spotting where new methodologies and research methods might be applied Others © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

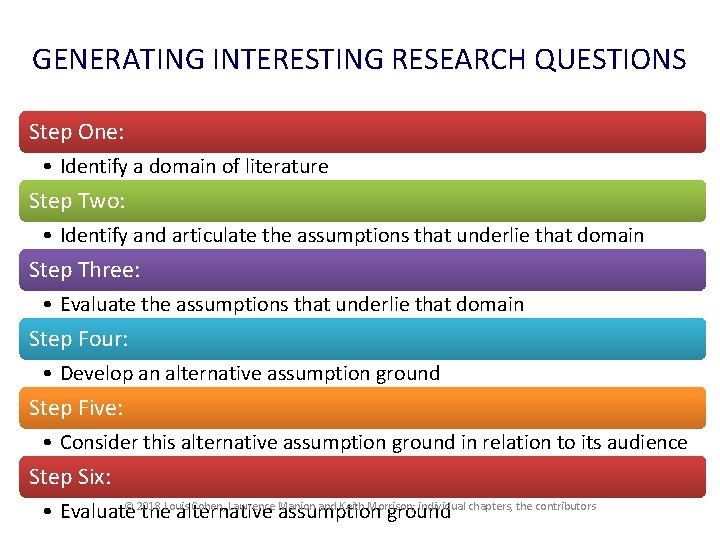

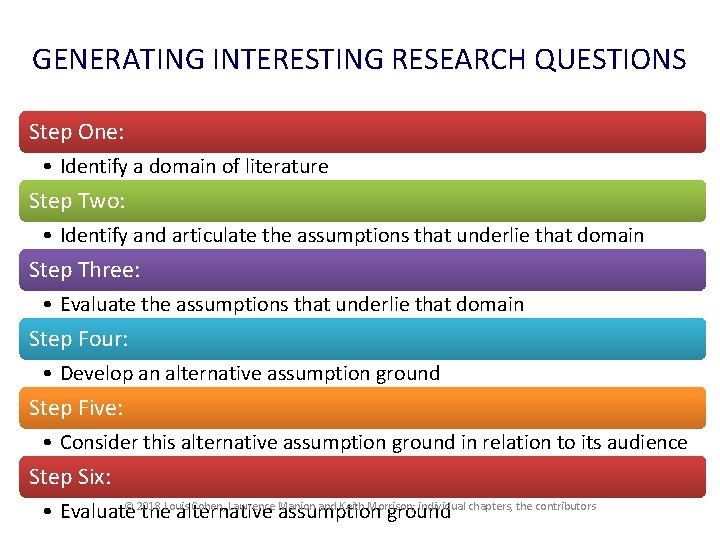

GENERATING INTERESTING RESEARCH QUESTIONS Step One: • Identify a domain of literature Step Two: • Identify and articulate the assumptions that underlie that domain Step Three: • Evaluate the assumptions that underlie that domain Step Four: • Develop an alternative assumption ground Step Five: • Consider this alternative assumption ground in relation to its audience Step Six: © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors • Evaluate the alternative assumption ground

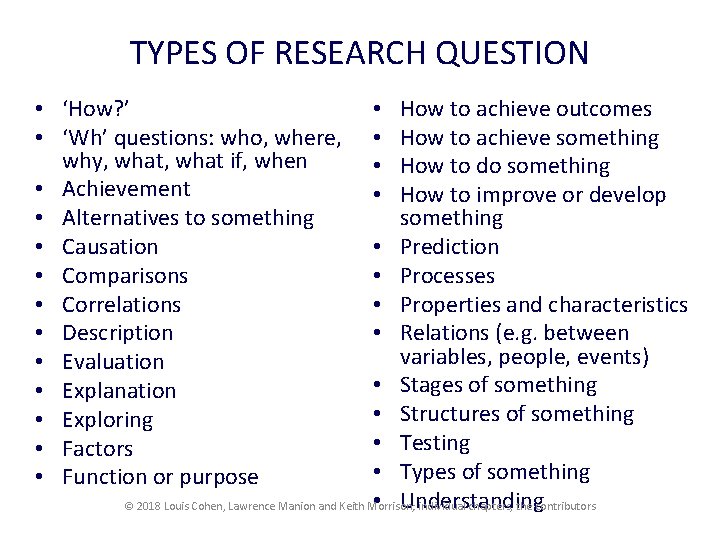

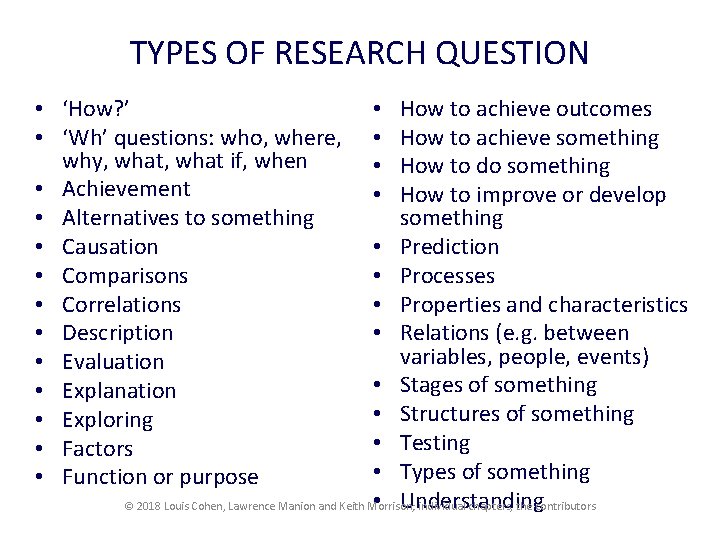

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTION • ‘How? ’ • ‘Wh’ questions: who, where, why, what if, when • Achievement • Alternatives to something • Causation • Comparisons • Correlations • Description • Evaluation • Explanation • Exploring • Factors • Function or purpose How to achieve outcomes How to achieve something How to do something How to improve or develop something • Prediction • Processes • Properties and characteristics • Relations (e. g. between variables, people, events) • Stages of something • Structures of something • Testing • Types of something • Understanding © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors • •

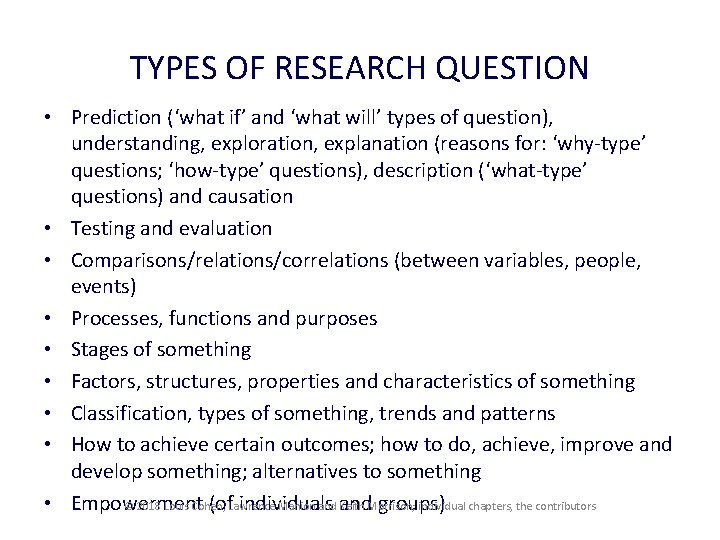

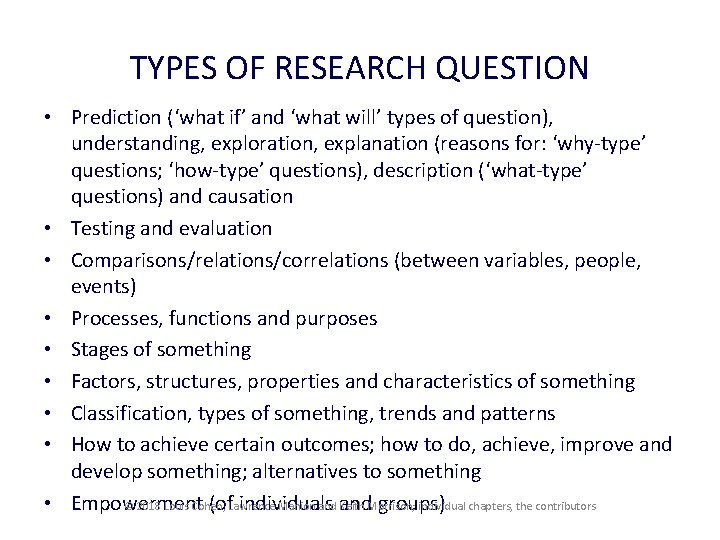

TYPES OF RESEARCH QUESTION • Prediction (‘what if’ and ‘what will’ types of question), understanding, exploration, explanation (reasons for: ‘why-type’ questions; ‘how-type’ questions), description (‘what-type’ questions) and causation • Testing and evaluation • Comparisons/relations/correlations (between variables, people, events) • Processes, functions and purposes • Stages of something • Factors, structures, properties and characteristics of something • Classification, types of something, trends and patterns • How to achieve certain outcomes; how to do, achieve, improve and develop something; alternatives to something • Empowerment (of. Lawrence individuals groups) © 2018 Louis Cohen, Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

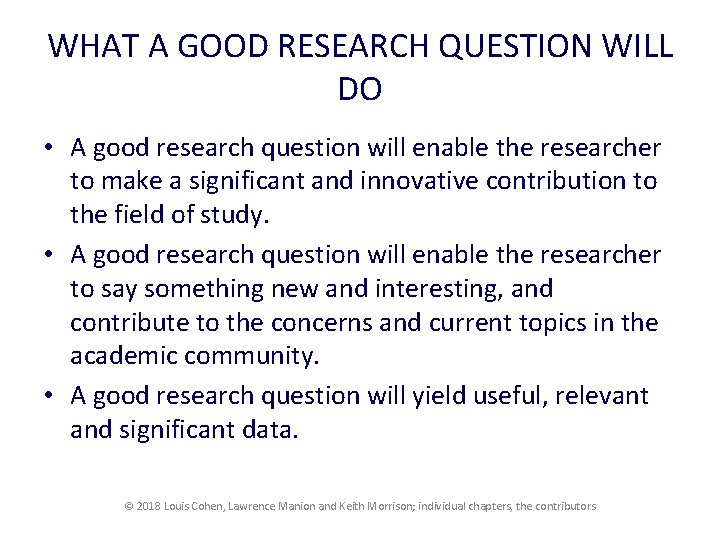

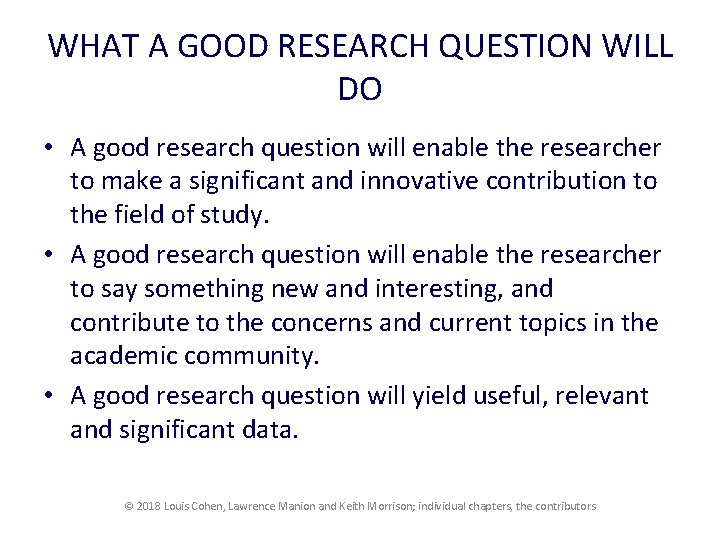

WHAT A GOOD RESEARCH QUESTION WILL DO • A good research question will enable the researcher to make a significant and innovative contribution to the field of study. • A good research question will enable the researcher to say something new and interesting, and contribute to the concerns and current topics in the academic community. • A good research question will yield useful, relevant and significant data. © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

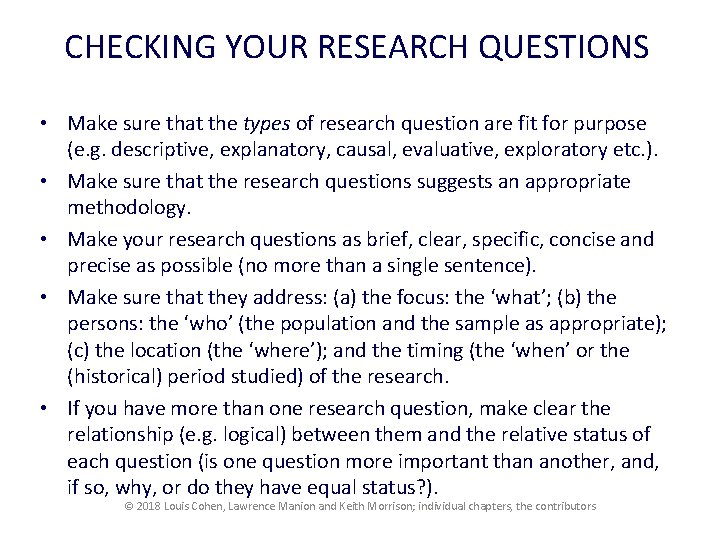

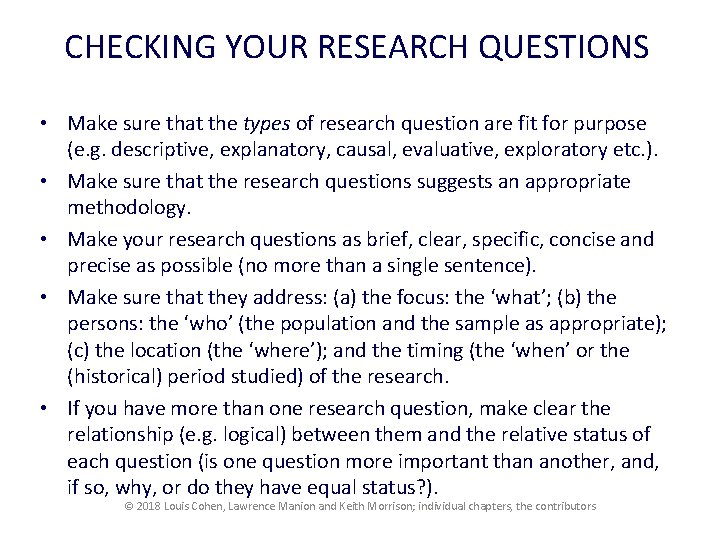

CHECKING YOUR RESEARCH QUESTIONS • Make sure that the types of research question are fit for purpose (e. g. descriptive, explanatory, causal, evaluative, exploratory etc. ). • Make sure that the research questions suggests an appropriate methodology. • Make your research questions as brief, clear, specific, concise and precise as possible (no more than a single sentence). • Make sure that they address: (a) the focus: the ‘what’; (b) the persons: the ‘who’ (the population and the sample as appropriate); (c) the location (the ‘where’); and the timing (the ‘when’ or the (historical) period studied) of the research. • If you have more than one research question, make clear the relationship (e. g. logical) between them and the relative status of each question (is one question more important than another, and, if so, why, or do they have equal status? ). © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

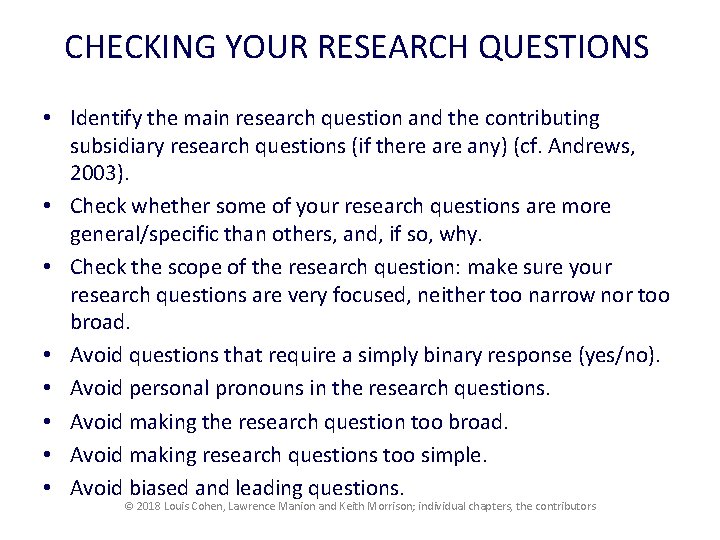

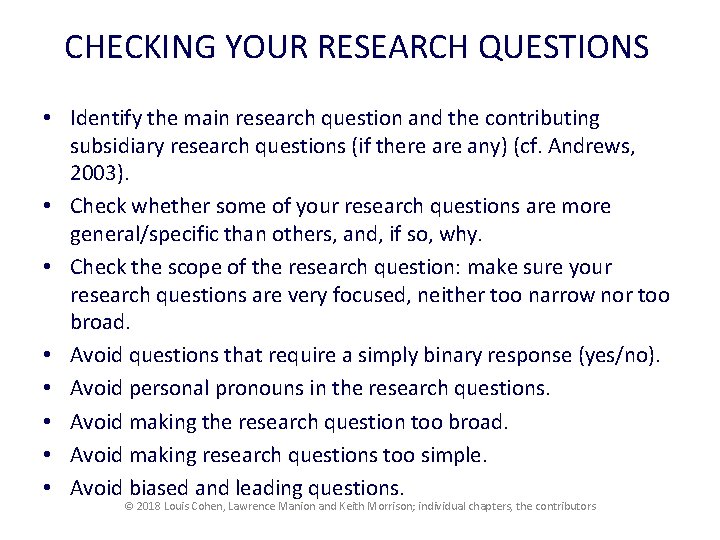

CHECKING YOUR RESEARCH QUESTIONS • Identify the main research question and the contributing subsidiary research questions (if there any) (cf. Andrews, 2003). • Check whether some of your research questions are more general/specific than others, and, if so, why. • Check the scope of the research question: make sure your research questions are very focused, neither too narrow nor too broad. • Avoid questions that require a simply binary response (yes/no). • Avoid personal pronouns in the research questions. • Avoid making the research question too broad. • Avoid making research questions too simple. • Avoid biased and leading questions. © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

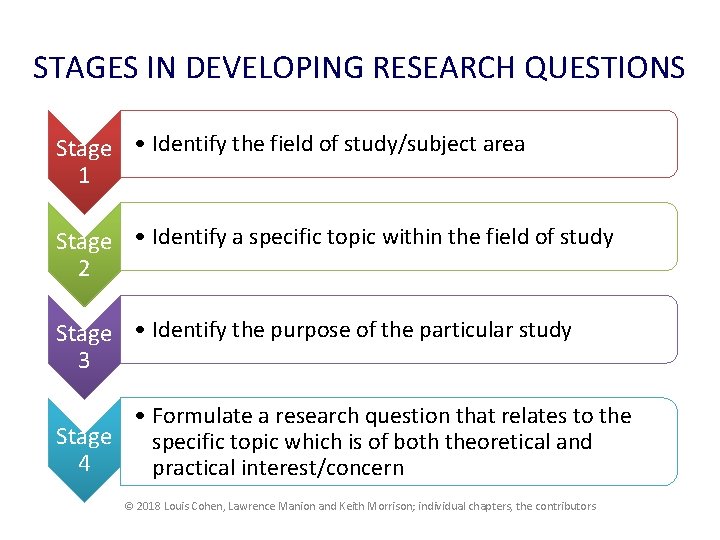

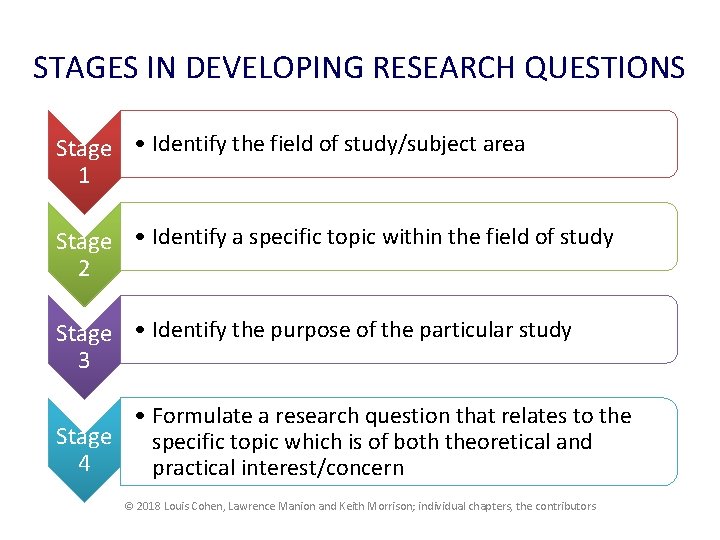

STAGES IN DEVELOPING RESEARCH QUESTIONS Stage • Identify the field of study/subject area 1 Stage • Identify a specific topic within the field of study 2 Stage • Identify the purpose of the particular study 3 • Formulate a research question that relates to the Stage specific topic which is of both theoretical and 4 practical interest/concern © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

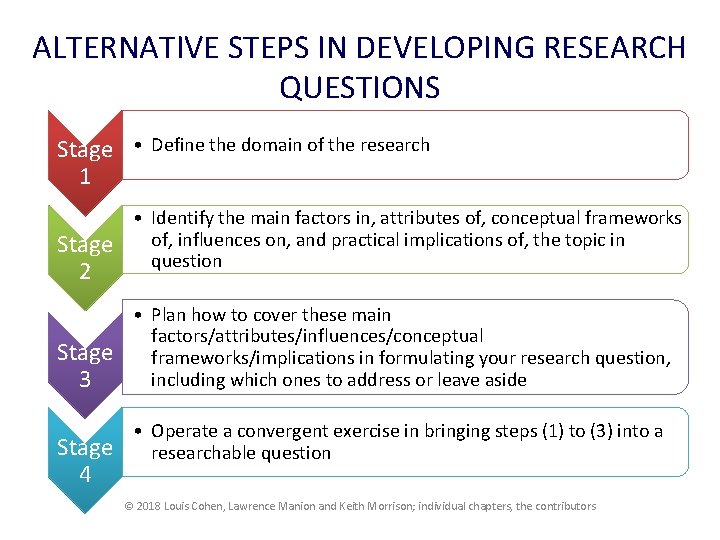

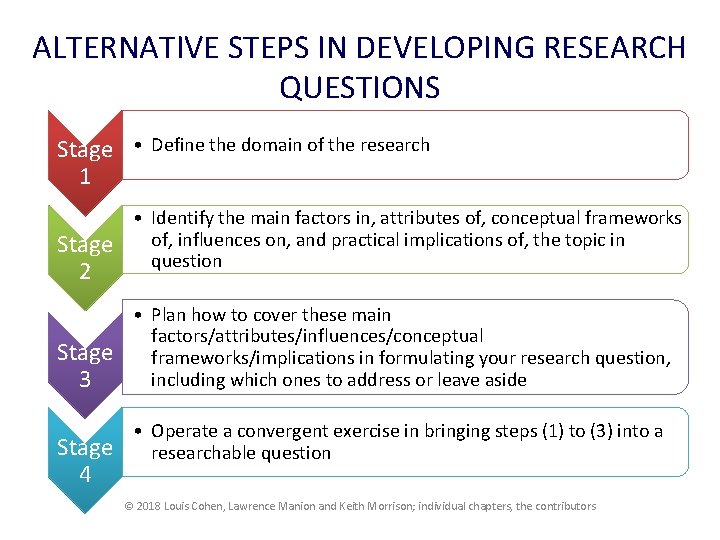

ALTERNATIVE STEPS IN DEVELOPING RESEARCH QUESTIONS Stage • 1 Stage 2 Stage 3 Stage 4 Define the domain of the research • Identify the main factors in, attributes of, conceptual frameworks of, influences on, and practical implications of, the topic in question • Plan how to cover these main factors/attributes/influences/conceptual frameworks/implications in formulating your research question, including which ones to address or leave aside • Operate a convergent exercise in bringing steps (1) to (3) into a researchable question © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

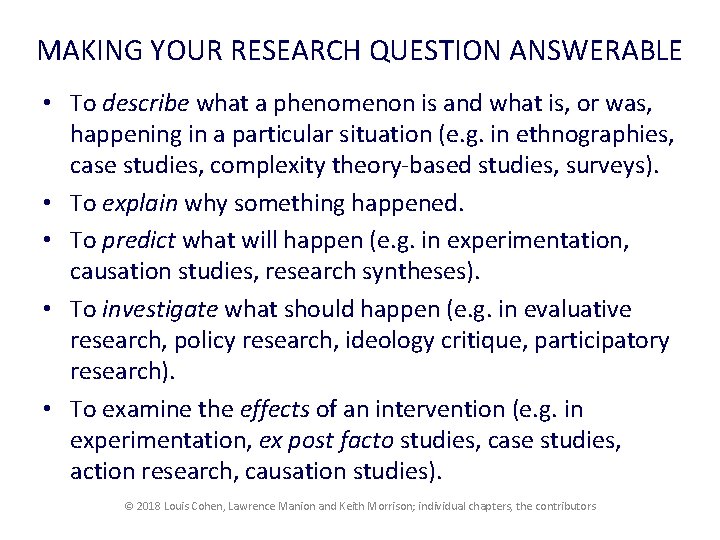

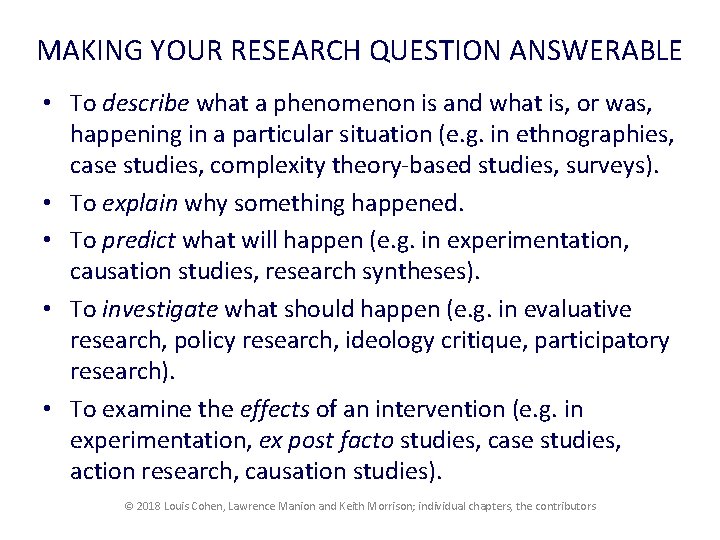

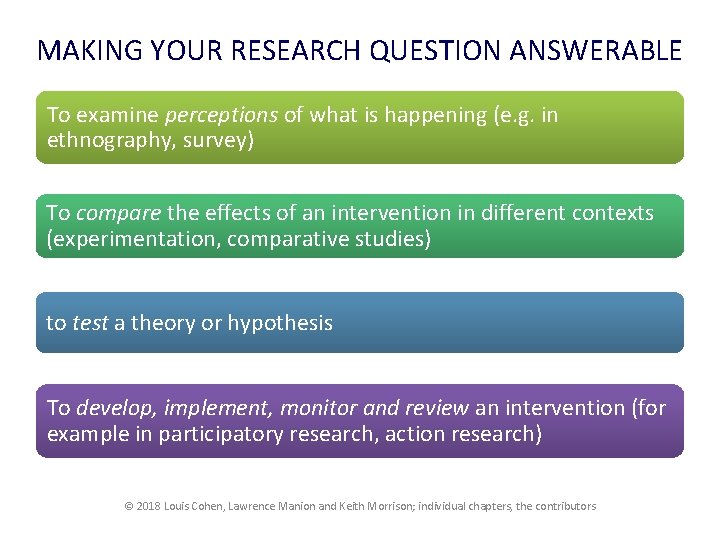

MAKING YOUR RESEARCH QUESTION ANSWERABLE • To describe what a phenomenon is and what is, or was, happening in a particular situation (e. g. in ethnographies, case studies, complexity theory-based studies, surveys). • To explain why something happened. • To predict what will happen (e. g. in experimentation, causation studies, research syntheses). • To investigate what should happen (e. g. in evaluative research, policy research, ideology critique, participatory research). • To examine the effects of an intervention (e. g. in experimentation, ex post facto studies, case studies, action research, causation studies). © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

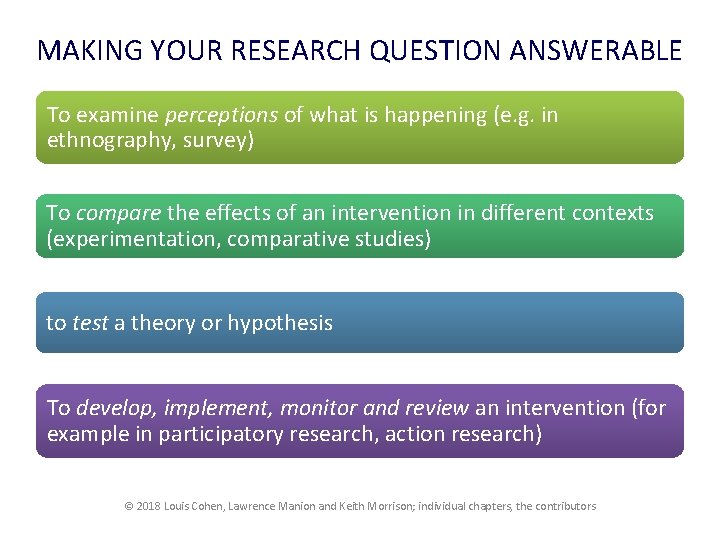

MAKING YOUR RESEARCH QUESTION ANSWERABLE To examine perceptions of what is happening (e. g. in ethnography, survey) To compare the effects of an intervention in different contexts (experimentation, comparative studies) to test a theory or hypothesis To develop, implement, monitor and review an intervention (for example in participatory research, action research) © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

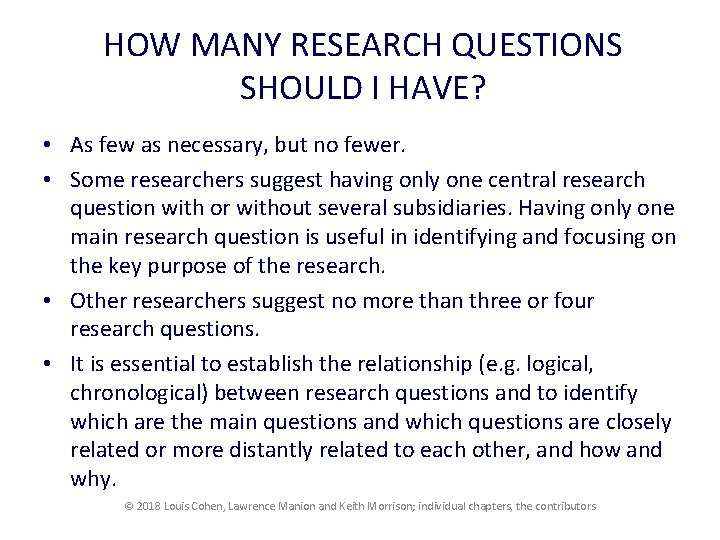

HOW MANY RESEARCH QUESTIONS SHOULD I HAVE? • As few as necessary, but no fewer. • Some researchers suggest having only one central research question with or without several subsidiaries. Having only one main research question is useful in identifying and focusing on the key purpose of the research. • Other researchers suggest no more than three or four research questions. • It is essential to establish the relationship (e. g. logical, chronological) between research questions and to identify which are the main questions and which questions are closely related or more distantly related to each other, and how and why. © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

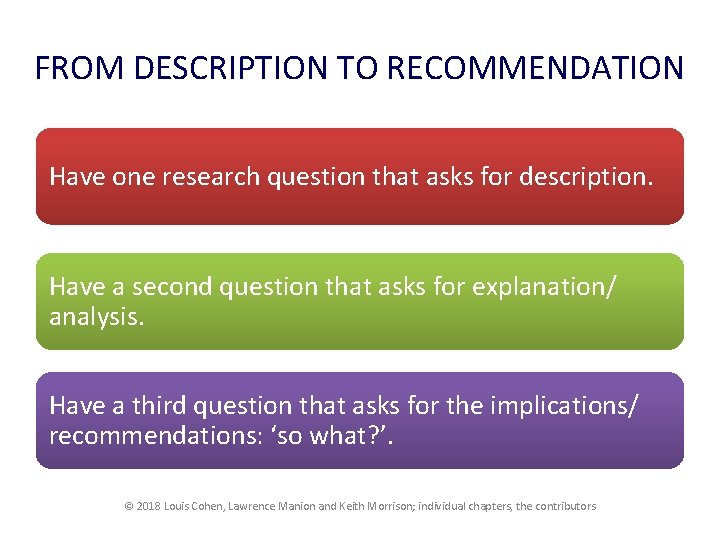

FROM DESCRIPTION TO RECOMMENDATION Have one research question that asks for description. Have a second question that asks for explanation/ analysis. Have a third question that asks for the implications/ recommendations: ‘so what? ’. © 2018 Louis Cohen, Lawrence Manion and Keith Morrison; individual chapters, the contributors

Cohen manion and morrison 2018

Cohen manion and morrison 2018 Ex post facto study example

Ex post facto study example Cohen manion and morrison 2018

Cohen manion and morrison 2018 Cohen manion & morrison 2018

Cohen manion & morrison 2018 Cohen manion and morrison 2018

Cohen manion and morrison 2018 Cohen manion and morrison 2018

Cohen manion and morrison 2018 Lawrence manion

Lawrence manion N=z2pq/d2

N=z2pq/d2 Cohen manion morrison

Cohen manion morrison Lawrence manion

Lawrence manion Mininova torrent

Mininova torrent Dr bruce cohen st louis mo

Dr bruce cohen st louis mo Louis vuitton history timeline

Louis vuitton history timeline Aiden cohen

Aiden cohen Pocket classification

Pocket classification Cohen-sutherland algorithm

Cohen-sutherland algorithm Keith and shuttleworth gender theory

Keith and shuttleworth gender theory Charles & keith sg

Charles & keith sg Keith haring moses and the burning bush

Keith haring moses and the burning bush Deflection of veins at av crossing

Deflection of veins at av crossing