Freedom of expression versus Defamation Insult Hate Speech

- Slides: 22

Freedom of expression versus Defamation, Insult, Hate Speech in the Context of Fundamental Principles of Liberal Democracy Ph. Dr. Kálmán Petőcz, Ph. D. , Slovakia Contribution at the National Convention on the European Union in the Republic of North Macedonia (NCEU-MK) Working group – 3, 16 March 2021

Freedom of expression as one of the most important human rights � Freedom of expression is one of the most important human rights. � Still, freedom of expression is not an absolute right – it can be subject to restrictions, as defined in Article 19, paragraph 3 and, Article 20 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, as well as Article 10, paragraph 2 of the European Convention on Human Rights. � Freedom to hold opinions, which is an element of the freedom of expression, is considered by the ICCPR as an absolute right

Why is Fo. E such important? Why is it, still, subject to restrictions? � Exactly for the very same reason: � Freedom of expression is very closely related to all three fundamental building blocs/principles of the liberal democracy: � - representative government (system of democratic institutions) � - rule of law (system of laws and rules providing legislative&procedural framework for democracy) � - culture of human rights (obligations of states to respect, protect and promote/fulfil individual human rights)

Fo. E and political democracy � Crucial elements of representative government as a system of institutions: � - political pluralism, free competition of (political) ideas � - free and fair elections, as well as other means of democratic civic participation � - system of checks and balances of power, incl. division of power � - public control of power (via media or other forms) � Neither of these elements can function properly without freedom to hold opinions and freedom of expression

Fo. E and the rule of law � Freedom of expression is indispensable for the realisation of the folowing principles of the rule of law: � - transparency and accountability, legal certainty � - right to fair trial and right to remedy � - legality (correct, transparent and participative process of drafting and adopting legislation)

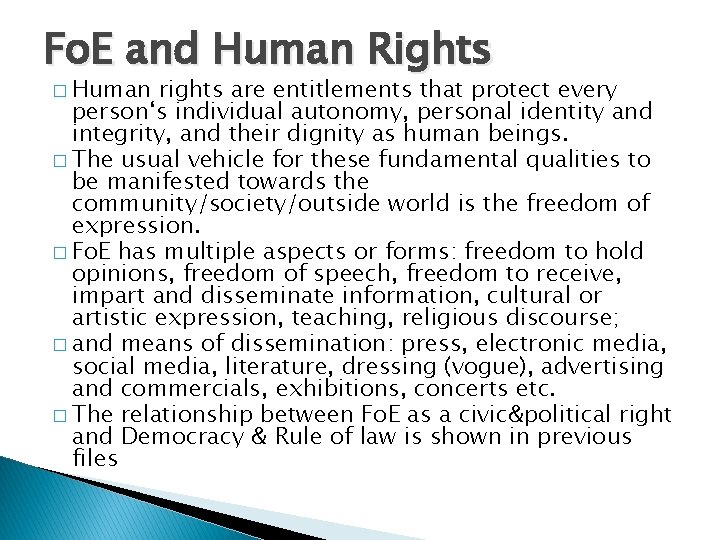

Fo. E and Human Rights � Human rights are entitlements that protect every person‘s individual autonomy, personal identity and integrity, and their dignity as human beings. � The usual vehicle for these fundamental qualities to be manifested towards the community/society/outside world is the freedom of expression. � Fo. E has multiple aspects or forms: freedom to hold opinions, freedom of speech, freedom to receive, impart and disseminate information, cultural or artistic expression, teaching, religious discourse; � and means of dissemination: press, electronic media, social media, literature, dressing (vogue), advertising and commercials, exhibitions, concerts etc. � The relationship between Fo. E as a civic&political right and Democracy & Rule of law is shown in previous files

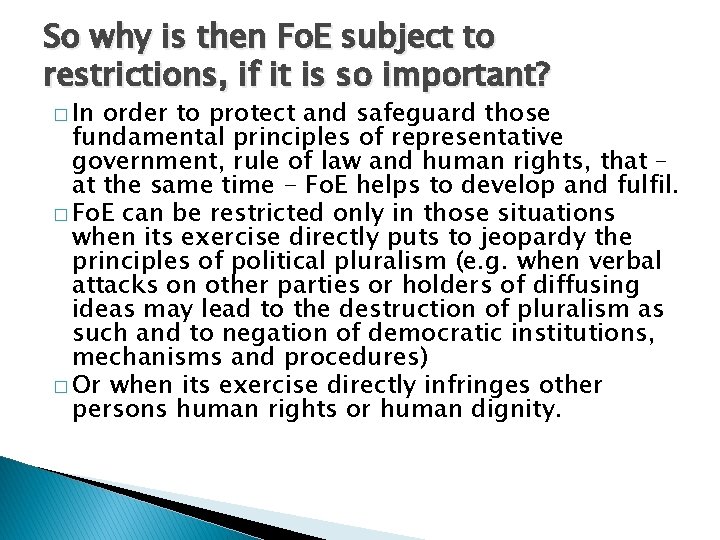

So why is then Fo. E subject to restrictions, if it is so important? � In order to protect and safeguard those fundamental principles of representative government, rule of law and human rights, that – at the same time - Fo. E helps to develop and fulfil. � Fo. E can be restricted only in those situations when its exercise directly puts to jeopardy the principles of political pluralism (e. g. when verbal attacks on other parties or holders of diffusing ideas may lead to the destruction of pluralism as such and to negation of democratic institutions, mechanisms and procedures) � Or when its exercise directly infringes other persons human rights or human dignity.

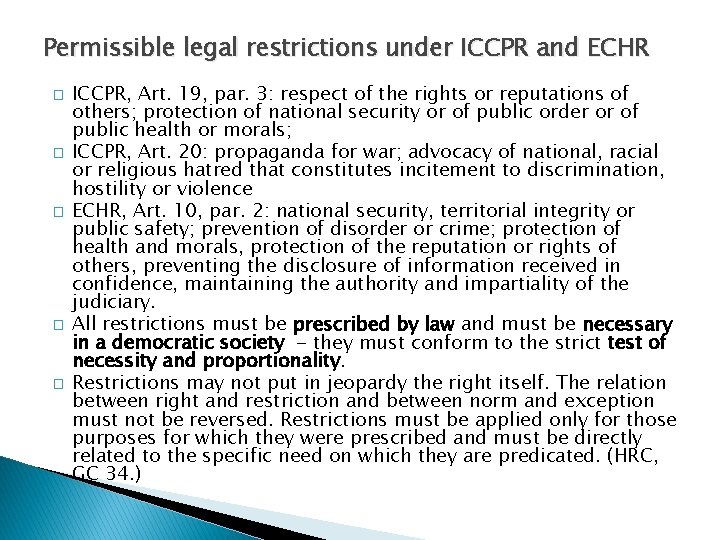

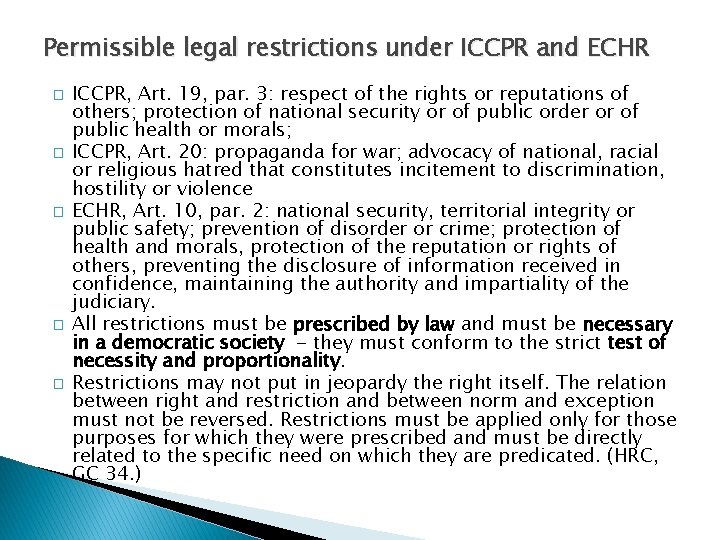

Permissible legal restrictions under ICCPR and ECHR � � � ICCPR, Art. 19, par. 3: respect of the rights or reputations of others; protection of national security or of public order or of public health or morals; ICCPR, Art. 20: propaganda for war; advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence ECHR, Art. 10, par. 2: national security, territorial integrity or public safety; prevention of disorder or crime; protection of health and morals, protection of the reputation or rights of others, preventing the disclosure of information received in confidence, maintaining the authority and impartiality of the judiciary. All restrictions must be prescribed by law and must be necessary in a democratic society - they must conform to the strict test of necessity and proportionality. Restrictions may not put in jeopardy the right itself. The relation between right and restriction and between norm and exception must not be reversed. Restrictions must be applied only for those purposes for which they were prescribed and must be directly related to the specific need on which they are predicated. (HRC, GC 34. )

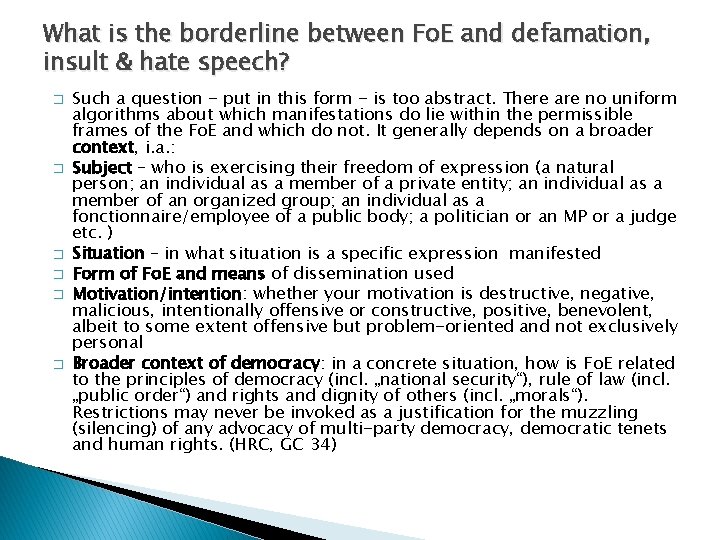

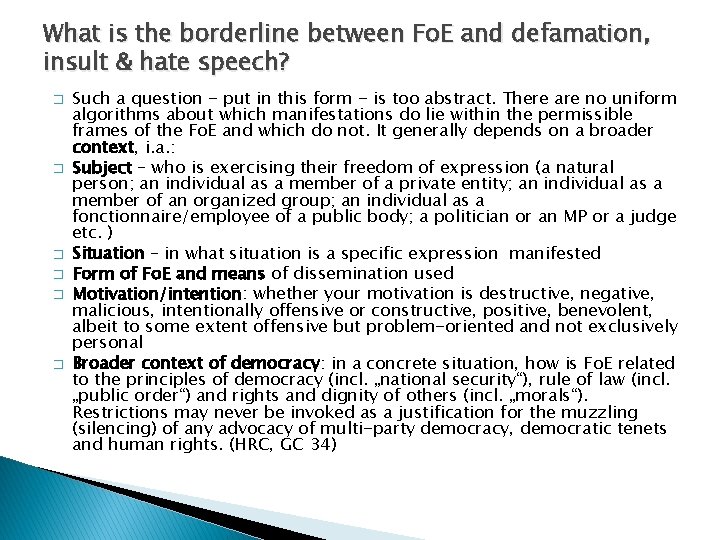

What is the borderline between Fo. E and defamation, insult & hate speech? � � � Such a question - put in this form - is too abstract. There are no uniform algorithms about which manifestations do lie within the permissible frames of the Fo. E and which do not. It generally depends on a broader context, i. a. : Subject – who is exercising their freedom of expression (a natural person; an individual as a member of a private entity; an individual as a member of an organized group; an individual as a fonctionnaire/employee of a public body; a politician or an MP or a judge etc. ) Situation – in what situation is a specific expression manifested Form of Fo. E and means of dissemination used Motivation/intention: whether your motivation is destructive, negative, malicious, intentionally offensive or constructive, positive, benevolent, albeit to some extent offensive but problem-oriented and not exclusively personal Broader context of democracy: in a concrete situation, how is Fo. E related to the principles of democracy (incl. „national security“), rule of law (incl. „public order“) and rights and dignity of others (incl. „morals“). Restrictions may never be invoked as a justification for the muzzling (silencing) of any advocacy of multi-party democracy, democratic tenets and human rights. (HRC, GC 34)

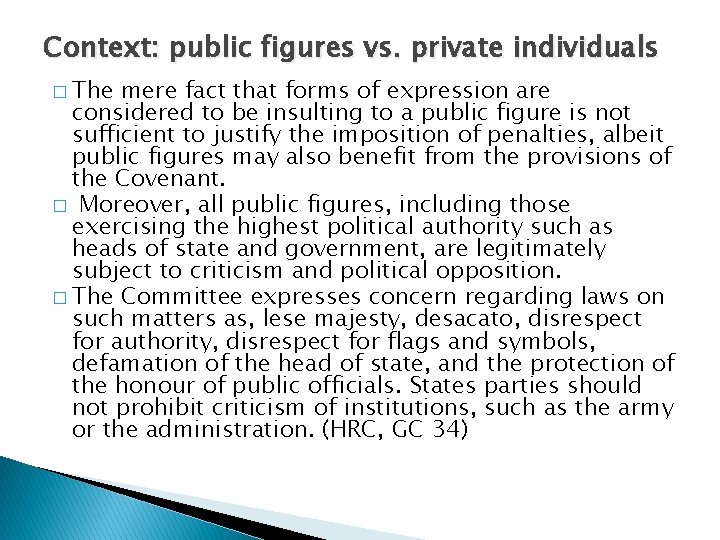

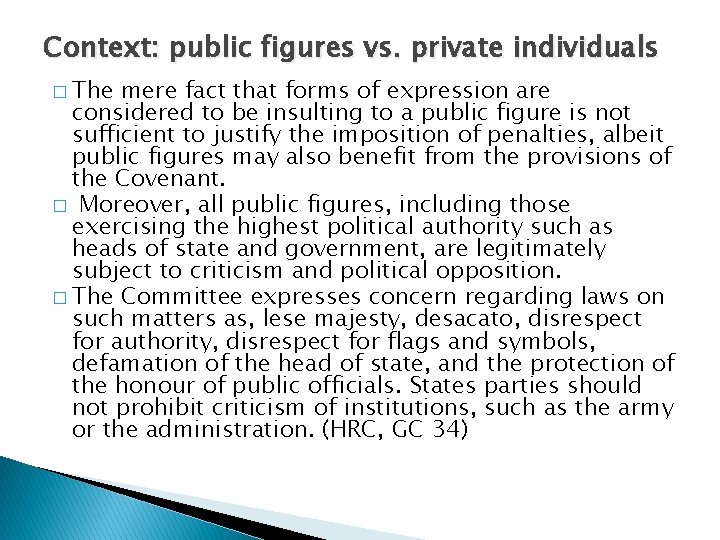

Context: public figures vs. private individuals � The mere fact that forms of expression are considered to be insulting to a public figure is not sufficient to justify the imposition of penalties, albeit public figures may also benefit from the provisions of the Covenant. � Moreover, all public figures, including those exercising the highest political authority such as heads of state and government, are legitimately subject to criticism and political opposition. � The Committee expresses concern regarding laws on such matters as, lese majesty, desacato, disrespect for authority, disrespect for flags and symbols, defamation of the head of state, and the protection of the honour of public officials. States parties should not prohibit criticism of institutions, such as the army or the administration. (HRC, GC 34)

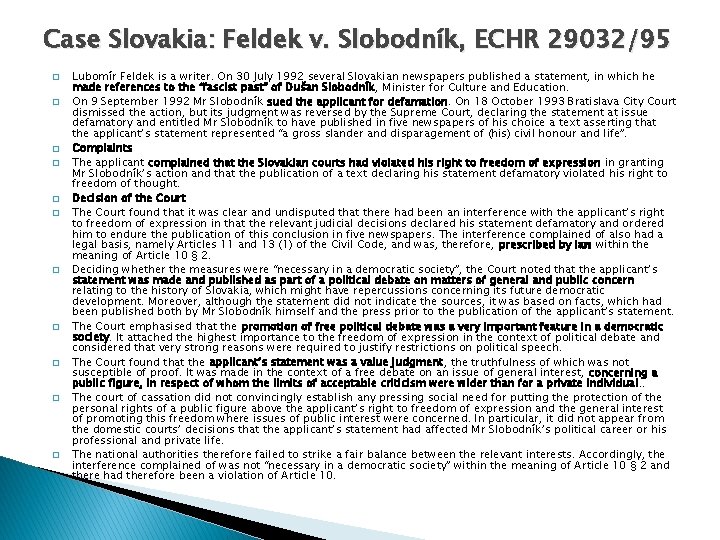

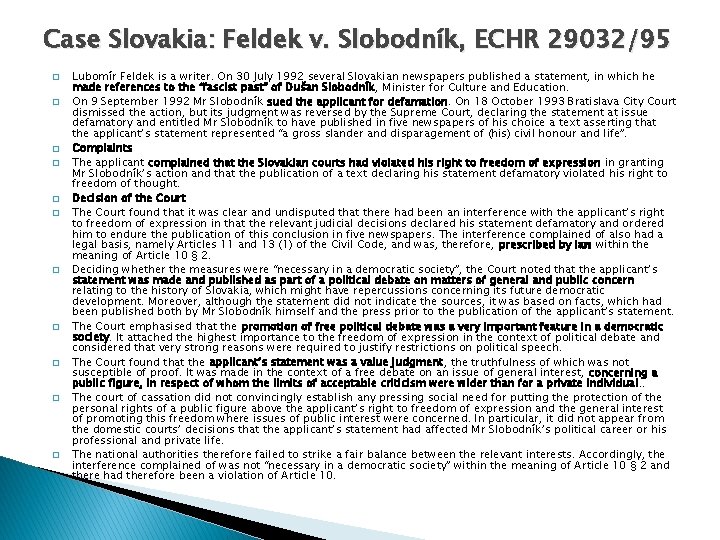

Case Slovakia: Feldek v. Slobodník, ECHR 29032/95 � � � Lubomír Feldek is a writer. On 30 July 1992 several Slovakian newspapers published a statement, in which he made references to the “fascist past” of Dušan Slobodník, Minister for Culture and Education. On 9 September 1992 Mr Slobodník sued the applicant for defamation. On 18 October 1993 Bratislava City Court dismissed the action, but its judgment was reversed by the Supreme Court, declaring the statement at issue defamatory and entitled Mr Slobodník to have published in five newspapers of his choice a text asserting that the applicant’s statement represented “a gross slander and disparagement of (his) civil honour and life”. Complaints The applicant complained that the Slovakian courts had violated his right to freedom of expression in granting Mr Slobodník’s action and that the publication of a text declaring his statement defamatory violated his right to freedom of thought. Decision of the Court The Court found that it was clear and undisputed that there had been an interference with the applicant’s right to freedom of expression in that the relevant judicial decisions declared his statement defamatory and ordered him to endure the publication of this conclusion in five newspapers. The interference complained of also had a legal basis, namely Articles 11 and 13 (1) of the Civil Code, and was, therefore, prescribed by law within the meaning of Article 10 § 2. Deciding whether the measures were “necessary in a democratic society”, the Court noted that the applicant’s statement was made and published as part of a political debate on matters of general and public concern relating to the history of Slovakia, which might have repercussions concerning its future democratic development. Moreover, although the statement did not indicate the sources, it was based on facts, which had been published both by Mr Slobodník himself and the press prior to the publication of the applicant’s statement. The Court emphasised that the promotion of free political debate was a very important feature in a democratic society. It attached the highest importance to the freedom of expression in the context of political debate and considered that very strong reasons were required to justify restrictions on political speech. The Court found that the applicant’s statement was a value judgment, the truthfulness of which was not susceptible of proof. It was made in the context of a free debate on an issue of general interest, concerning a public figure, in respect of whom the limits of acceptable criticism were wider than for a private individual. . The court of cassation did not convincingly establish any pressing social need for putting the protection of the personal rights of a public figure above the applicant’s right to freedom of expression and the general interest of promoting this freedom where issues of public interest were concerned. In particular, it did not appear from the domestic courts’ decisions that the applicant’s statement had affected Mr Slobodník’s political career or his professional and private life. The national authorities therefore failed to strike a fair balance between the relevant interests. Accordingly, the interference complained of was not “necessary in a democratic society” within the meaning of Article 10 § 2 and there had therefore been a violation of Article 10.

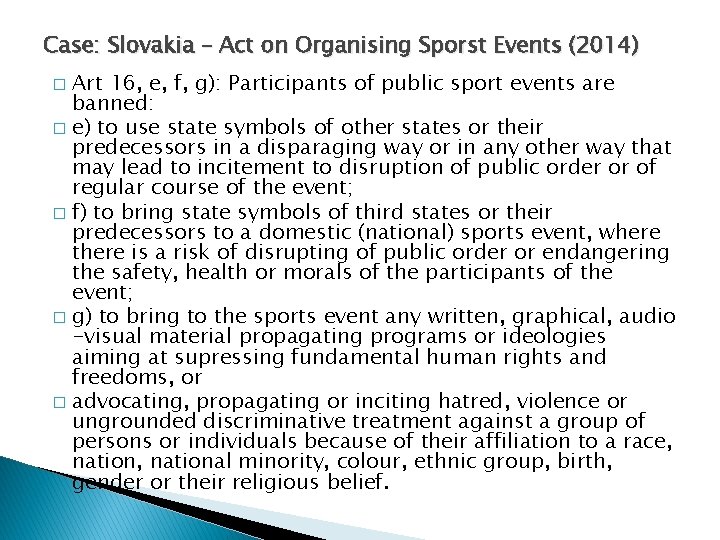

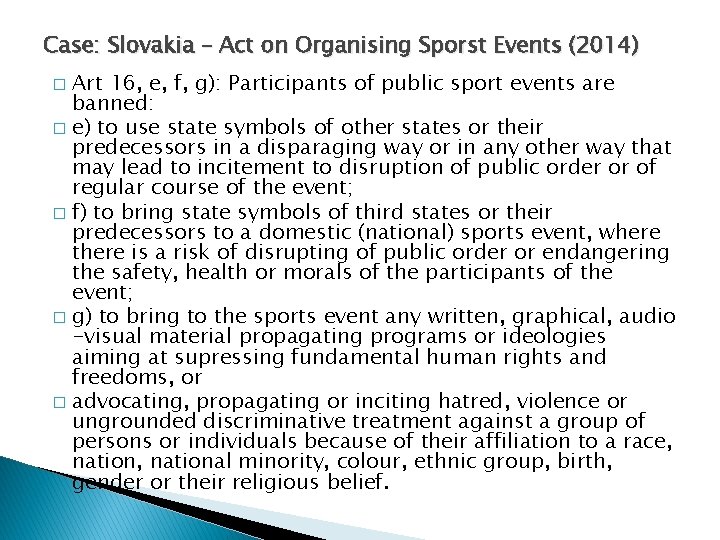

Case: Slovakia – Act on Organising Sporst Events (2014) Art 16, e, f, g): Participants of public sport events are banned: � e) to use state symbols of other states or their predecessors in a disparaging way or in any other way that may lead to incitement to disruption of public order or of regular course of the event; � f) to bring state symbols of third states or their predecessors to a domestic (national) sports event, where there is a risk of disrupting of public order or endangering the safety, health or morals of the participants of the event; � g) to bring to the sports event any written, graphical, audio -visual material propagating programs or ideologies aiming at supressing fundamental human rights and freedoms, or � advocating, propagating or inciting hatred, violence or ungrounded discriminative treatment against a group of persons or individuals because of their affiliation to a race, national minority, colour, ethnic group, birth, gender or their religious belief. �

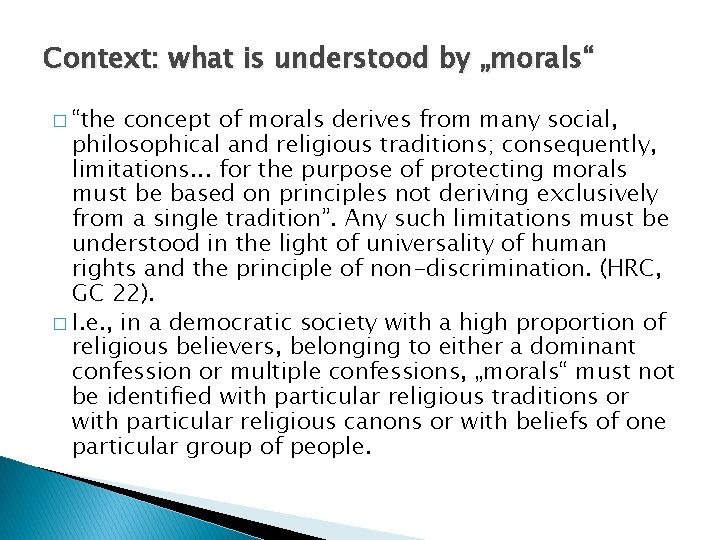

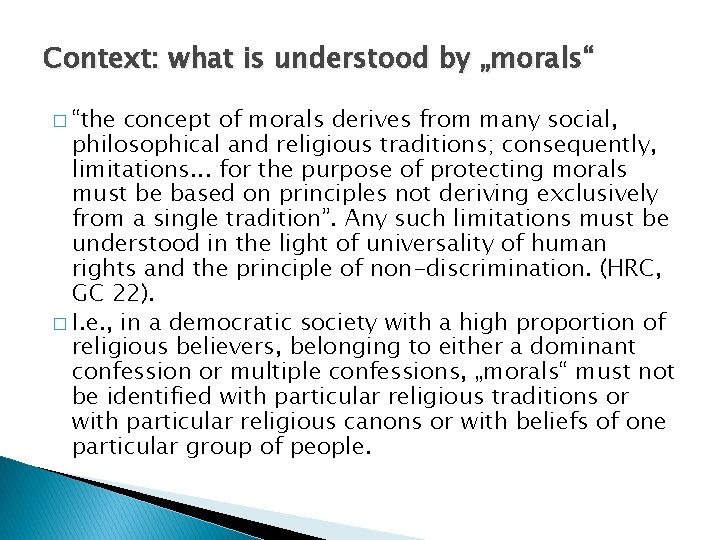

Context: what is understood by „morals“ � “the concept of morals derives from many social, philosophical and religious traditions; consequently, limitations. . . for the purpose of protecting morals must be based on principles not deriving exclusively from a single tradition”. Any such limitations must be understood in the light of universality of human rights and the principle of non-discrimination. (HRC, GC 22). � I. e. , in a democratic society with a high proportion of religious believers, belonging to either a dominant confession or multiple confessions, „morals“ must not be identified with particular religious traditions or with particular religious canons or with beliefs of one particular group of people.

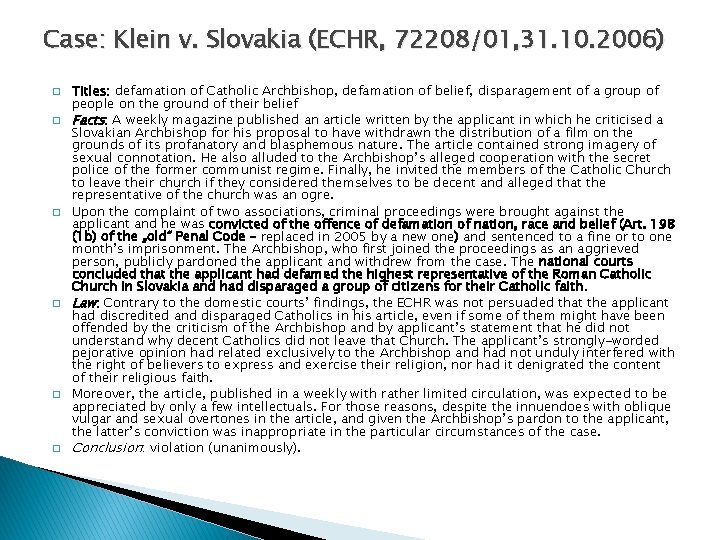

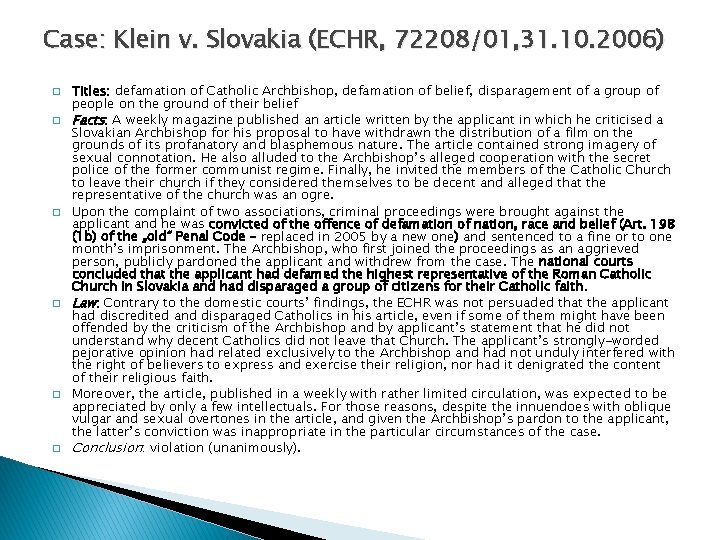

Case: Klein v. Slovakia (ECHR, 72208/01, 31. 10. 2006) � � � Titles: defamation of Catholic Archbishop, defamation of belief, disparagement of a group of people on the ground of their belief Facts: A weekly magazine published an article written by the applicant in which he criticised a Slovakian Archbishop for his proposal to have withdrawn the distribution of a film on the grounds of its profanatory and blasphemous nature. The article contained strong imagery of sexual connotation. He also alluded to the Archbishop’s alleged cooperation with the secret police of the former communist regime. Finally, he invited the members of the Catholic Church to leave their church if they considered themselves to be decent and alleged that the representative of the church was an ogre. Upon the complaint of two associations, criminal proceedings were brought against the applicant and he was convicted of the offence of defamation of nation, race and belief (Art. 198 (1 b) of the „old“ Penal Code – replaced in 2005 by a new one) and sentenced to a fine or to one month’s imprisonment. The Archbishop, who first joined the proceedings as an aggrieved person, publicly pardoned the applicant and withdrew from the case. The national courts concluded that the applicant had defamed the highest representative of the Roman Catholic Church in Slovakia and had disparaged a group of citizens for their Catholic faith. Law: Contrary to the domestic courts’ findings, the ECHR was not persuaded that the applicant had discredited and disparaged Catholics in his article, even if some of them might have been offended by the criticism of the Archbishop and by applicant’s statement that he did not understand why decent Catholics did not leave that Church. The applicant’s strongly-worded pejorative opinion had related exclusively to the Archbishop and had not unduly interfered with the right of believers to express and exercise their religion, nor had it denigrated the content of their religious faith. Moreover, the article, published in a weekly with rather limited circulation, was expected to be appreciated by only a few intellectuals. For those reasons, despite the innuendoes with oblique vulgar and sexual overtones in the article, and given the Archbishop’s pardon to the applicant, the latter’s conviction was inappropriate in the particular circumstances of the case. Conclusion: violation (unanimously).

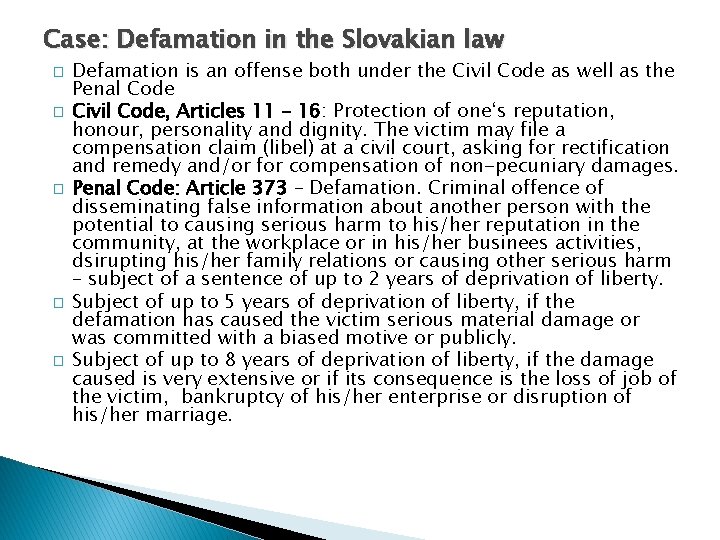

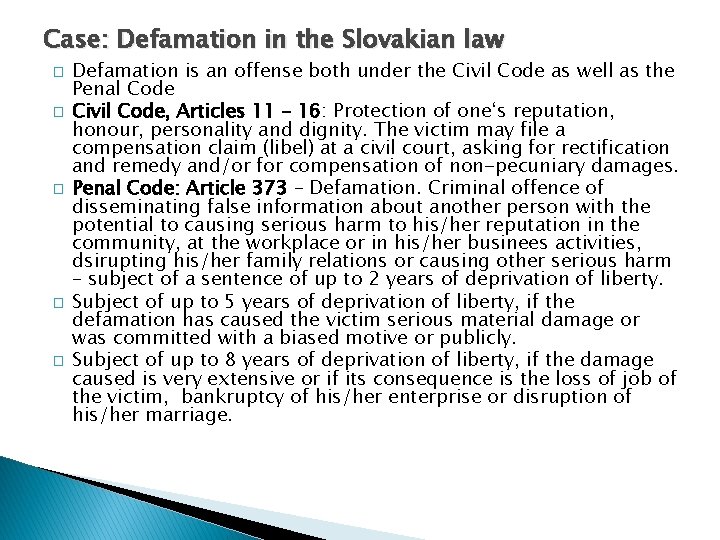

Case: Defamation in the Slovakian law � � � Defamation is an offense both under the Civil Code as well as the Penal Code Civil Code, Articles 11 – 16: Protection of one‘s reputation, honour, personality and dignity. The victim may file a compensation claim (libel) at a civil court, asking for rectification and remedy and/or for compensation of non-pecuniary damages. Penal Code: Article 373 – Defamation. Criminal offence of disseminating false information about another person with the potential to causing serious harm to his/her reputation in the community, at the workplace or in his/her businees activities, dsirupting his/her family relations or causing other serious harm – subject of a sentence of up to 2 years of deprivation of liberty. Subject of up to 5 years of deprivation of liberty, if the defamation has caused the victim serious material damage or was committed with a biased motive or publicly. Subject of up to 8 years of deprivation of liberty, if the damage caused is very extensive or if its consequence is the loss of job of the victim, bankruptcy of his/her enterprise or disruption of his/her marriage.

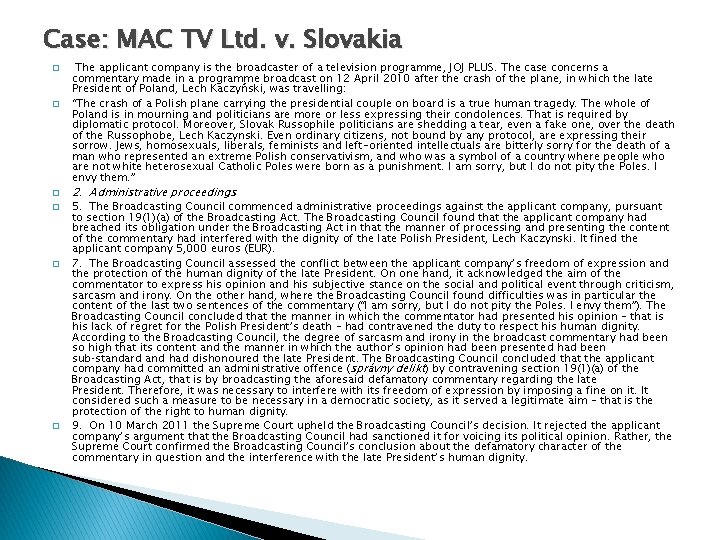

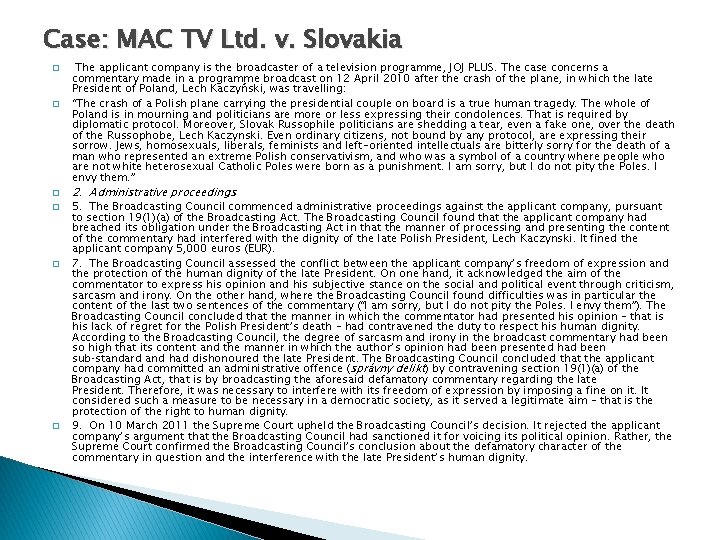

Case: MAC TV Ltd. v. Slovakia � � � The applicant company is the broadcaster of a television programme, JOJ PLUS. The case concerns a commentary made in a programme broadcast on 12 April 2010 after the crash of the plane, in which the late President of Poland, Lech Kaczyński, was travelling: “The crash of a Polish plane carrying the presidential couple on board is a true human tragedy. The whole of Poland is in mourning and politicians are more or less expressing their condolences. That is required by diplomatic protocol. Moreover, Slovak Russophile politicians are shedding a tear, even a fake one, over the death of the Russophobe, Lech Kaczynski. Even ordinary citizens, not bound by any protocol, are expressing their sorrow. Jews, homosexuals, liberals, feminists and left-oriented intellectuals are bitterly sorry for the death of a man who represented an extreme Polish conservativism, and who was a symbol of a country where people who are not white heterosexual Catholic Poles were born as a punishment. I am sorry, but I do not pity the Poles. I envy them. ” 2. Administrative proceedings 5. The Broadcasting Council commenced administrative proceedings against the applicant company, pursuant to section 19(1)(a) of the Broadcasting Act. The Broadcasting Council found that the applicant company had breached its obligation under the Broadcasting Act in that the manner of processing and presenting the content of the commentary had interfered with the dignity of the late Polish President, Lech Kaczynski. It fined the applicant company 5, 000 euros (EUR). 7. The Broadcasting Council assessed the conflict between the applicant company’s freedom of expression and the protection of the human dignity of the late President. On one hand, it acknowledged the aim of the commentator to express his opinion and his subjective stance on the social and political event through criticism, sarcasm and irony. On the other hand, where the Broadcasting Council found difficulties was in particular the content of the last two sentences of the commentary (“I am sorry, but I do not pity the Poles. I envy them”). The Broadcasting Council concluded that the manner in which the commentator had presented his opinion – that is his lack of regret for the Polish President’s death – had contravened the duty to respect his human dignity. According to the Broadcasting Council, the degree of sarcasm and irony in the broadcast commentary had been so high that its content and the manner in which the author’s opinion had been presented had been sub‑standard and had dishonoured the late President. The Broadcasting Council concluded that the applicant company had committed an administrative offence (správny delikt) by contravening section 19(1)(a) of the Broadcasting Act, that is by broadcasting the aforesaid defamatory commentary regarding the late President. Therefore, it was necessary to interfere with its freedom of expression by imposing a fine on it. It considered such a measure to be necessary in a democratic society, as it served a legitimate aim – that is the protection of the right to human dignity. 9. On 10 March 2011 the Supreme Court upheld the Broadcasting Council’s decision. It rejected the applicant company’s argument that the Broadcasting Council had sanctioned it for voicing its political opinion. Rather, the Supreme Court confirmed the Broadcasting Council’s conclusion about the defamatory character of the commentary in question and the interference with the late President’s human dignity.

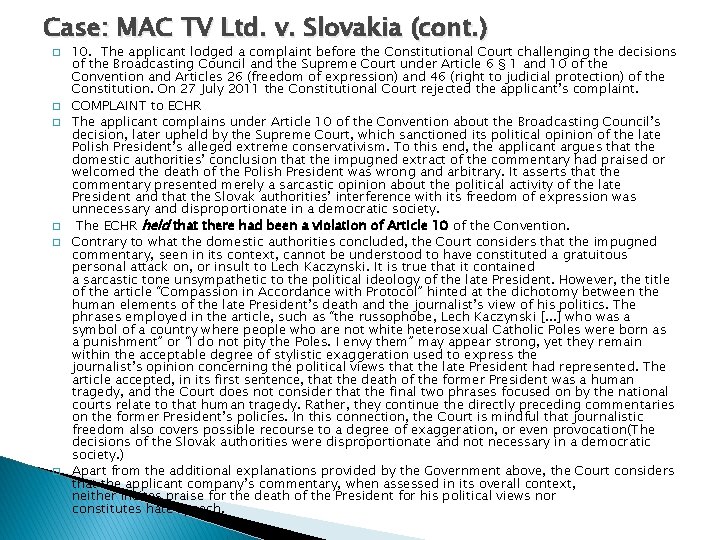

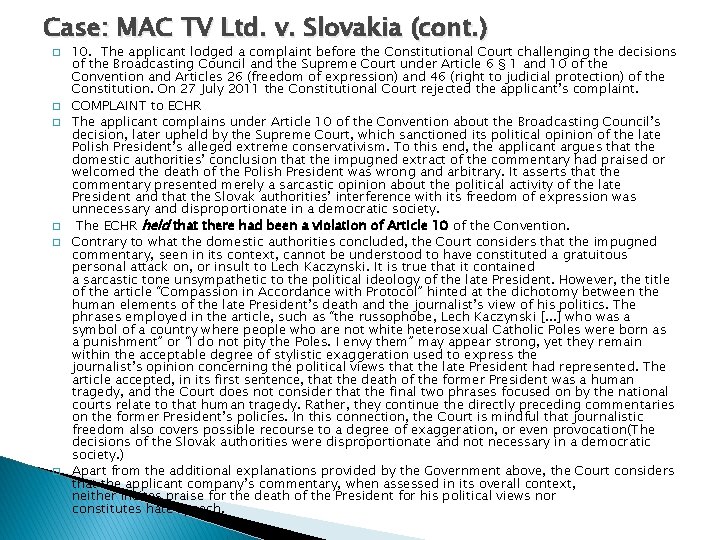

Case: MAC TV Ltd. v. Slovakia (cont. ) � � � 10. The applicant lodged a complaint before the Constitutional Court challenging the decisions of the Broadcasting Council and the Supreme Court under Article 6 § 1 and 10 of the Convention and Articles 26 (freedom of expression) and 46 (right to judicial protection) of the Constitution. On 27 July 2011 the Constitutional Court rejected the applicant’s complaint. COMPLAINT to ECHR The applicant complains under Article 10 of the Convention about the Broadcasting Council’s decision, later upheld by the Supreme Court, which sanctioned its political opinion of the late Polish President’s alleged extreme conservativism. To this end, the applicant argues that the domestic authorities’ conclusion that the impugned extract of the commentary had praised or welcomed the death of the Polish President was wrong and arbitrary. It asserts that the commentary presented merely a sarcastic opinion about the political activity of the late President and that the Slovak authorities’ interference with its freedom of expression was unnecessary and disproportionate in a democratic society. The ECHR held that there had been a violation of Article 10 of the Convention. Contrary to what the domestic authorities concluded, the Court considers that the impugned commentary, seen in its context, cannot be understood to have constituted a gratuitous personal attack on, or insult to Lech Kaczynski. It is true that it contained a sarcastic tone unsympathetic to the political ideology of the late President. However, the title of the article “Compassion in Accordance with Protocol” hinted at the dichotomy between the human elements of the late President’s death and the journalist’s view of his politics. The phrases employed in the article, such as “the russophobe, Lech Kaczynski [. . . ] who was a symbol of a country where people who are not white heterosexual Catholic Poles were born as a punishment” or “I do not pity the Poles. I envy them” may appear strong, yet they remain within the acceptable degree of stylistic exaggeration used to express the journalist’s opinion concerning the political views that the late President had represented. The article accepted, in its first sentence, that the death of the former President was a human tragedy, and the Court does not consider that the final two phrases focused on by the national courts relate to that human tragedy. Rather, they continue the directly preceding commentaries on the former President’s policies. In this connection, the Court is mindful that journalistic freedom also covers possible recourse to a degree of exaggeration, or even provocation(The decisions of the Slovak authorities were disproportionate and not necessary in a democratic society. ) Apart from the additional explanations provided by the Government above, the Court considers that the applicant company’s commentary, when assessed in its overall context, neither incites praise for the death of the President for his political views nor constitutes hate‑speech.

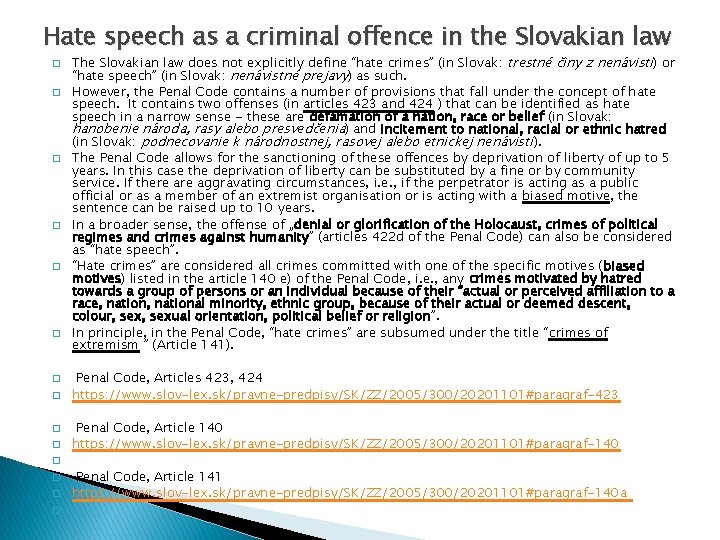

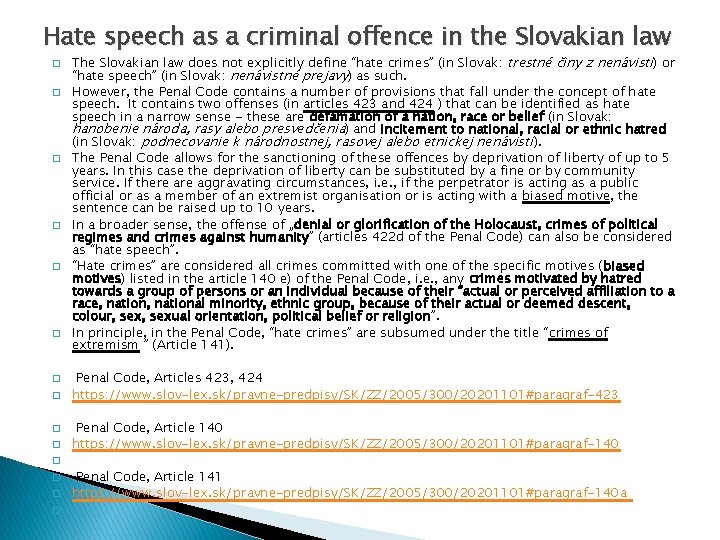

Hate speech as a criminal offence in the Slovakian law � � � � � The Slovakian law does not explicitly define “hate crimes” (in Slovak: trestné činy z nenávisti ) or “hate speech” (in Slovak: nenávistné prejavy) as such. However, the Penal Code contains a number of provisions that fall under the concept of hate speech. It contains two offenses (in articles 423 and 424 ) that can be identified as hate speech in a narrow sense - these are defamation of a nation, race or belief (in Slovak: hanobenie národa, rasy alebo presvedčenia) and incitement to national, racial or ethnic hatred (in Slovak: podnecovanie k národnostnej, rasovej alebo etnickej nenávisti ). The Penal Code allows for the sanctioning of these offences by deprivation of liberty of up to 5 years. In this case the deprivation of liberty can be substituted by a fine or by community service. If there aggravating circumstances, i. e. , if the perpetrator is acting as a public official or as a member of an extremist organisation or is acting with a biased motive, the sentence can be raised up to 10 years. In a broader sense, the offense of „denial or glorification of the Holocaust, crimes of political regimes and crimes against humanity” (articles 422 d of the Penal Code) can also be considered as “hate speech”. “Hate crimes” are considered all crimes committed with one of the specific motives (biased motives) listed in the article 140 e) of the Penal Code, i. e. , any crimes motivated by hatred towards a group of persons or an individual because of their “actual or perceived affiliation to a race, national minority, ethnic group, because of their actual or deemed descent, colour, sexual orientation, political belief or religion”. In principle, in the Penal Code, “hate crimes” are subsumed under the title “crimes of extremism ” (Article 141). Penal Code, Articles 423, 424 https: //www. slov-lex. sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2005/300/20201101#paragraf-423 Penal Code, Article 140 https: //www. slov-lex. sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2005/300/20201101#paragraf-140 � � Penal Code, Article 141 https: //www. slov-lex. sk/pravne-predpisy/SK/ZZ/2005/300/20201101#paragraf-140 a

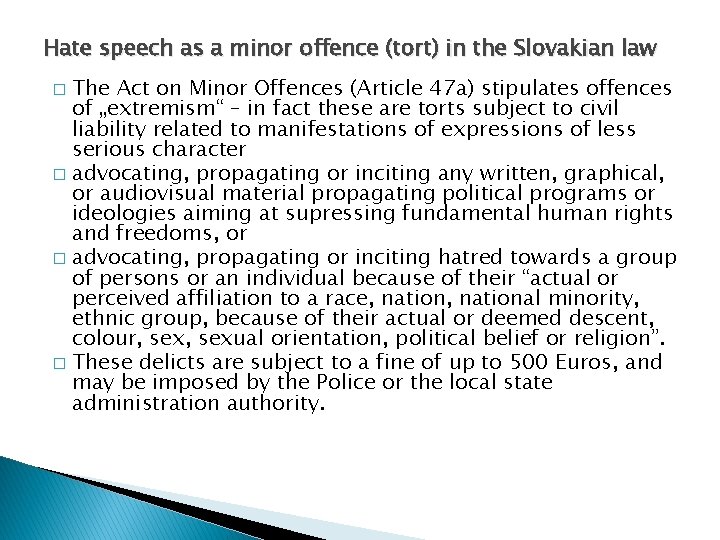

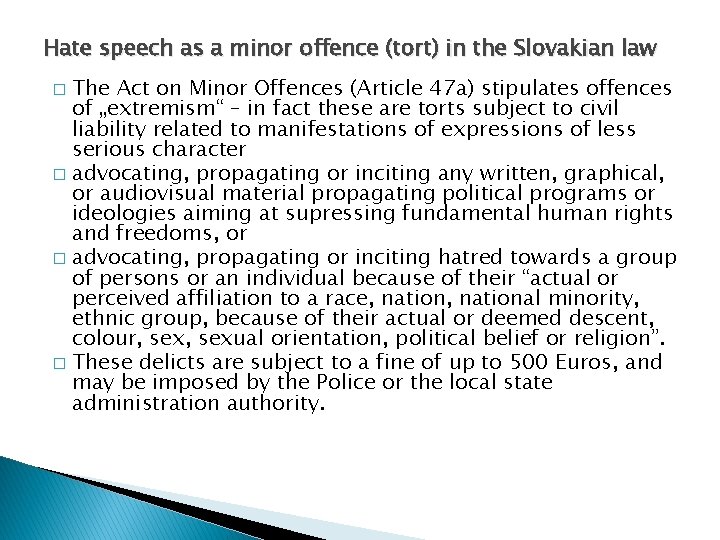

Hate speech as a minor offence (tort) in the Slovakian law The Act on Minor Offences (Article 47 a) stipulates offences of „extremism“ – in fact these are torts subject to civil liability related to manifestations of expressions of less serious character � advocating, propagating or inciting any written, graphical, or audiovisual material propagating political programs or ideologies aiming at supressing fundamental human rights and freedoms, or � advocating, propagating or inciting hatred towards a group of persons or an individual because of their “actual or perceived affiliation to a race, national minority, ethnic group, because of their actual or deemed descent, colour, sexual orientation, political belief or religion”. � These delicts are subject to a fine of up to 500 Euros, and may be imposed by the Police or the local state administration authority. �

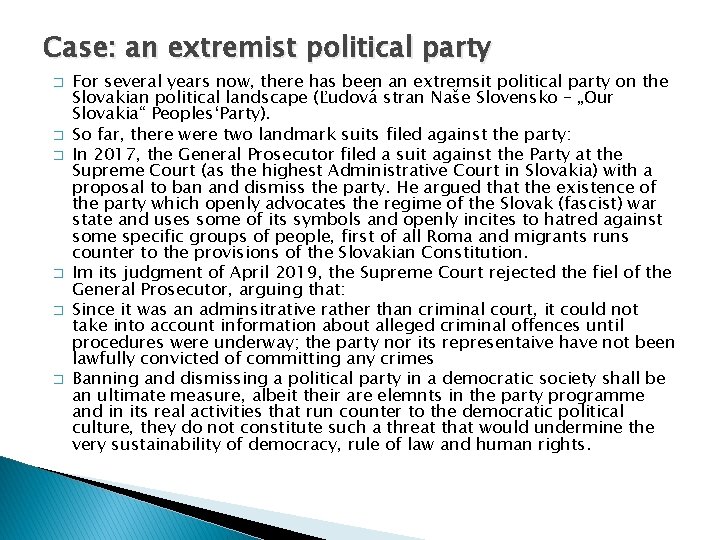

Case: an extremist political party � � � For several years now, there has been an extremsit political party on the Slovakian political landscape (Ľudová stran Naše Slovensko – „Our Slovakia“ Peoples‘Party). So far, there were two landmark suits filed against the party: In 2017, the General Prosecutor filed a suit against the Party at the Supreme Court (as the highest Administrative Court in Slovakia) with a proposal to ban and dismiss the party. He argued that the existence of the party which openly advocates the regime of the Slovak (fascist) war state and uses some of its symbols and openly incites to hatred against some specific groups of people, first of all Roma and migrants runs counter to the provisions of the Slovakian Constitution. Im its judgment of April 2019, the Supreme Court rejected the fiel of the General Prosecutor, arguing that: Since it was an adminsitrative rather than criminal court, it could not take into account information about alleged criminal offences until procedures were underway; the party nor its representaive have not been lawfully convicted of committing any crimes Banning and dismissing a political party in a democratic society shall be an ultimate measure, albeit their are elemnts in the party programme and in its real activities that run counter to the democratic political culture, they do not constitute such a threat that would undermine the very sustainability of democracy, rule of law and human rights.

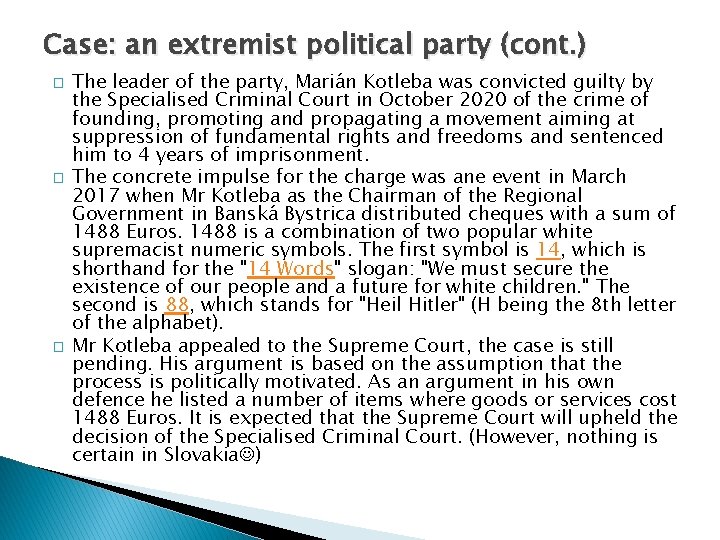

Case: an extremist political party (cont. ) � � � The leader of the party, Marián Kotleba was convicted guilty by the Specialised Criminal Court in October 2020 of the crime of founding, promoting and propagating a movement aiming at suppression of fundamental rights and freedoms and sentenced him to 4 years of imprisonment. The concrete impulse for the charge was ane event in March 2017 when Mr Kotleba as the Chairman of the Regional Government in Banská Bystrica distributed cheques with a sum of 1488 Euros. 1488 is a combination of two popular white supremacist numeric symbols. The first symbol is 14, which is shorthand for the "14 Words" slogan: "We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children. " The second is 88, which stands for "Heil Hitler" (H being the 8 th letter of the alphabet). Mr Kotleba appealed to the Supreme Court, the case is still pending. His argument is based on the assumption that the process is politically motivated. As an argument in his own defence he listed a number of items where goods or services cost 1488 Euros. It is expected that the Supreme Court will upheld the decision of the Specialised Criminal Court. (However, nothing is certain in Slovakia )

Thank you for your attention!

What is defamation

What is defamation Example of defamation

Example of defamation Libel vs slander

Libel vs slander Positive freedom negative freedom

Positive freedom negative freedom Glorious freedom wonderful freedom

Glorious freedom wonderful freedom Freedom versus determinism

Freedom versus determinism How old are janie and jody now?

How old are janie and jody now? Forgive adjective form

Forgive adjective form Which statement best summarizes freedom of expression?

Which statement best summarizes freedom of expression? I want freedom for the full expression of my personality

I want freedom for the full expression of my personality Hate reported speech

Hate reported speech 10 things i hate about you speech

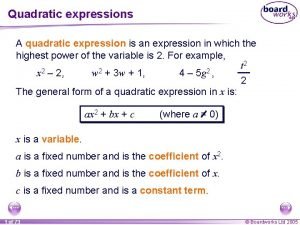

10 things i hate about you speech Linear term

Linear term Freedom and responsibility speech

Freedom and responsibility speech Chapter 19 section 3 freedom of speech and press

Chapter 19 section 3 freedom of speech and press Why does freedom of speech have limits

Why does freedom of speech have limits Chapter 19 section 3 freedom of speech and press

Chapter 19 section 3 freedom of speech and press Direct versus indirect speech

Direct versus indirect speech People really hate elephants on compact cars

People really hate elephants on compact cars Carol went shopping yesterday

Carol went shopping yesterday I hate hype

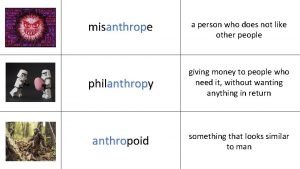

I hate hype Misanthropic philanthropist

Misanthropic philanthropist Love and hate poem

Love and hate poem