Eugene ONeills Masterpeice Long Days Journey into Night

- Slides: 30

Eugene O’Neill’s Masterpeice Long Day’s Journey into Night O’Neill’s Dramatic Devices in Revealing the Pas & His New Techniques of Expression

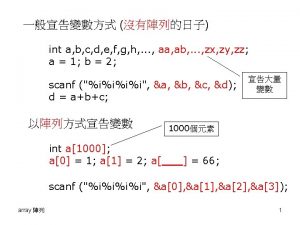

O’Neill’s New Techniques of Expression

Eugene O’Neill held theatre as an art rather than a commercial enterprise. He wrote dramas with different types of form such as realism, expressionism, comedy, myth and modern versions of Greek Tragedy. **the expressionistic techniques are used in his plays to highlight theatrical effect of the rupture between the two sides of an individual human being, the private and the public.

In expressionistic plays, the playwright's subjective sense of reality finds expression. The characters and the milieu may be realistic, but their presentation on stage is controlled by the writer's personal biases and inclinations. No longer a camera photograph, the stage could be highly elaborate or bare; the accompanying lighting, costumes, music, and scenery could be similarly non-realistic. More like a dream, expressionistic writing has no recognizable plot, conflicts, and character developments. However, the threads are still audience friendly; expressionism is not absurdism or an exercise in obscurity.

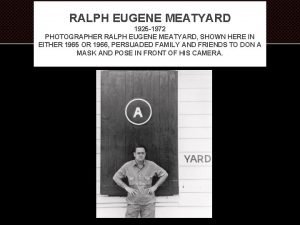

*O'Neill's plays were written from an intensely personal point of view, deriving directly from the scarring effects of his family's tragic relationships— his mother and father, who loved and tormented each other; his older brother, who loved and corrupted him and died of alcoholism in middle age; and O'Neill himself, caught and torn between love for and rage at all three. Long Day’s journey into Night. Is a play of real strength.

O’Neill sought to deal with man’s inner strengths and his subconscious and quickly found, like the naturalists, that realism failed to probe deeply enough. Thus, Expressionism became a major technique, complementing his earlier naturalistic bent. O’Neill’s experimented with monologue, trilogies, symbolism, divided characters, and masks.

O’Neill’s Used Main Technique of Expressionism He dramatizes the project onto the stage an internal , subconscious or symbolic reality very objectively. He has written his own story as an outsider. As if they don't have enough to deal with, the Tyrones start getting busy making things worse. Act II, Scene Two and Act III brings about the escalation of infighting. Mary's morphine addiction is back and worse than ever, Edmund has consumption, and the men in the family start drinking a bit too much. Basically, the Tyrones' conflicts become clear and we see that they have very serious problems.

Expressionism is essentially a method of distertion of reality in order to represent a particular and personal point of view. It is in fact a doctrine of individual and personal self expression. The charactristic of this doctrine include : A dream like and night marish atmosphere and an episodic plot or structure. Perhaps, if Long Day’s Journey into Night may be called a “dream play, ” an explanation might lie in the fact that Edmund is the dreamer’s dream of himself. He moves like a dream’s protagonist in wonder and dread, but is uncommitted to the dream’s occurrences. Commitment, finally, belongs to the dreamer and not the dream. The play is O’Neill’s last mirror, the last time he would look to see if he was “there. ” In itself, the image of the young, gentle, unhappy man he saw proved nothing, but having gone through the door in the mind to the fogbound room in the past, he perhaps understood himself as his figure was illuminated by the pain and concern of those about

The play’s voice; This is a play without a narrator, and therefore has no particular narrative voice. It might be worth pointing out, though, that the audience seems to be intended to identify the most with Edmund. The tone of the play toward the other characters is quite a forgiving, which is consistent with Edmund's overall disposition. This comparison makes a lot of sense, when you think about the fact that Edmund is O'Neill's fictional recreation of himself.

There is no Antagonist in the play. (Nobody/Everybody) Even though we think there is some room to argue that Mary is the protagonist, we should point out that most folks agree the play just doesn't have one protagonist. While Mary does seem to be the focus, she doesn't do quite enough for some critics to dub her the protagonist. Basically, she takes morphine, blames everybody else, and takes another hit. If she is a protagonist she's an inactive one. None of the other Tyrones do much, either. There may be some small case to be made for Edmund. He's the most blameless of the Tyrones, and could be seen as a window for the audience. The fact of the matter is, though, that he does very little. Mostly he just sits around drinking and getting bad news. He's one of the most passive characters in the

The argument could be made that (though Mary is the closest) there's no one character that drives the action of the play. Long Day's Journey doesn't really have a larger overarching plot. It's really just a series of smaller repetitive actions. The Tyrones hurt each other then forgive. It's the same thing over and over again. The play shows a family caught in a vicious cycle of hate and love. Perhaps, rather than saying that nobody is the protagonist, we should say that everybody is.

The play was staged successfully in 1926. Although it was too metaphysically intricate, it was significant for its symbolic use of masks and for the experimentation with expressionistic dialogue and action—devices that since have become commonly accepted both on the stage and in motion pictures. "Everything looked and sounded unreal. Nothing was what it is. That's what I wanted-to be alone with myself in another world where truth is untrue and life can hide from itself. " Act 4 Edmund speaks of his feelings as he walked home in the fog.

"The Mad Scene. Enter Ophelia!" Act 4 Jamie's sardonic remark when his mother enters the room, apparently unaware of her surroundings. "None of us can help the things life has done to us. " Act 2, scene 1 Mary tries to excuse her son Jamie for his faults, but her comment reveals her attitude to herself as well. "I hate doctors! They'll do anything-anything to keep you coming back to them. They'll sell their souls! What's worse, they'll sell yours, and you never know it till one day you find yourself in hell!" Act 2, scene 2 Mary gives vent to her anger.

Escape from reality is the oblivion the characters seek in alcohol, in memory or in narrating the story of their lives again and again in hope to create those lives anew. Spanning one day in the life of a family, the play strips away layer after layer from each of the four central figures, revealing the mother as a defeated drug addict, the father as a man frustrated in his career and failed as a husband father, the older son as a bitter alcoholic, and the younger son as a tubercular, disillusioned youth with only the slenderest chance for physical and spiritual survival

O’Neill’s Dramatic Devices in Revealing the Past

note that Long Day's Journey into Night is not only a journey forward in time, but also a journey back into the past lives of all the characters, who continually dip back into their old lifestyles. We are left as an audience realizing that the family is not making progress towards betterment, but rather continually sliding into despair, as they remain bound to a past that they can neither forget nor forgive.

THE STORY WAS MORE OF AN ESCAPE OF PAST TROUBLES THAN A SEARCH FOR MORE OPPORTUNITIES. I can't forget the past, " says Jamie in Act 1. He is talking about his mother's long history of drug addiction, but the comment has a wider significance. Almost every interaction the family has during its long day's journey into night is affected or shaped in some way by the past. As Mary puts it, "The past is the present, isn't it? It's the future, too" (Act 2, scene 2). Much of the play is devoted to dramatizing how this situation came about. Tyrone's miserliness is responsible for much of it, and this is a recurring pattern. Just as Mary's drug addiction began as a result of Tyrone's unwillingness to pay for a competent doctor, so Edmund's life is imperiled by Tyrone's attempt to send him to a state sanatorium just to save money.

Because the troubles of the present are so deeply rooted in the past there is little forward movement in the play. The past exerts such a powerful grip that the characters believe there is little point in trying to change their situation. They best they can advocate is passive acceptance. "All we can do is try to be resigned -again" (Act 4) Tyrone says of his wife's addiction. In the case of Mary, the past finally wins in an almost literal sense, since she regresses to her girlhood at the convent and shuts out the present. There is no future for her, or for Tyrone or Jamie. Only Edmund shows signs of being able to break out of the binding grip of the past.

*The role of the past play in Long Day's Journey into Night for Mary in particular, the play is as much as long day's journey into the past as anything else. The characters are all to varying degrees obsessed with the past, and they are all unable to forget. Although O'Neill suggests that forgiveness can be an appropriate form of salvation, the characters have difficulty forgiving one another, too. The family is ultimately paralyzed because of its inability to let go of past pains and wrongs. Tyrone cannot be forgiven for his stinginess, and Mary cannot be forgiven for all the promises she has broken because of her addiction. The past is very much alive in the play, and all the characters tend to idealize it as a time when things were better.

The gradual revelation of these two medical disasters makes up most of the play's plot. In between these discoveries, however, the family constantly revisits old fights and opens old wounds left by the past, which the family members are never unable to forget. Tyrone, for example, is constantly blamed for his own stinginess, which may have led to Mary's morphine addiction when he refused to pay for a good doctor to treat the pain caused by childbirth. Mary, on the other hand, is never able to let go of the past or admit to the painful truth of the present, the truth that she is addicted to morphine and her youngest son has tuberculosis. They all argue over Jamie and Edmund's failure to become successes as their father had always hoped they would become.

The gradual revelation of these two medical disasters makes up most of the play's plot. In between these discoveries, however, the family constantly revisits old fights and opens old wounds left by the past, which the family members are never unable to forget. Tyrone, for example, is constantly blamed for his own stinginess, which may have led to Mary's morphine addiction when he refused to pay for a good doctor to treat the pain caused by childbirth. Mary, on the other hand, is never able to let go of the past or admit to the painful truth of the present, the truth that she is addicted to morphine and her youngest son has tuberculosis. They all argue over Jamie and Edmund's failure to become successes as their father had always hoped they would become.

There are other recurring patterns. Mary tries, not for the first time, to break her addiction, but she slides back into it. Jamie has never got beyond the habit of drunkenness he acquired from his father at an early age. Even Edmund's consumption is in a sense a repeated pattern, since Mary's father died of the same disease. All the arguments and accusations in the Tyrone household have been heard again and again, as Jamie's comment in Act 1 reveals: "I could see that line coming! God, how many thousand times-!"

Because the troubles of the present are so deeply rooted in the past there is little forward movement in the play. The past exerts such a powerful grip that the characters believe there is little point in trying to change their situation. They best they can advocate is passive acceptance. "All we can do is try to be resigned-again" (Act 4) Tyrone says of his wife's addiction. In the case of Mary, the past finally wins in an almost literal sense, since she regresses to her girlhood at the convent and shuts out the present. There is no future for her, or for Tyrone or Jamie. Only Edmund shows signs of being able to break out of the binding grip of the past.

The Prison of the Past The Tyrone family is in a prison of its own making. There have been so many events in the past that have had such a traumatic cumulative effect on them that the shadow of the past extends into the present and the future. It seems as if almost everything they say to each other is coloredpoisoned, it might be said-by something bad that has happened in the past, whether it is the numerous examples of Tyrone's miserliness, or the corrosive effects of Mary's addiction, or Jamie's laziness and drunkenness. The family is like a cart stuck in a ditch.

The prison of the past is all the more tragic because the play shows not only the behaviors that led them into their current situation, but also what each of the Tyrones might have been had life taken a different course, had the prison walls not been built. As a young girl, for example, Mary had innocence, romantic ideals, and a strong religious faith centered on the Virgin Mary. That faith disappeared early in her marriage, and she desperately wants to rekindle it, because that would offer a way out of the prison. The Virgin can offer divine forgiveness, whereas for humans, forgiveness does not come so easily. In the end, Mary's only response to her situation is to sink deeper and deeper into the past, as if she is in a kind of sad dream.

Like Mary, Tyrone was quite different as a young man. He seemed to be on the threshold of a brilliant career, when he was inspired by Shakespeare's plays and praised by the great actor Edmund Booth for his performance as Othello. But he allowed his miserliness, his materialism and his drinking to dominate his personality, and before he realized what was happening, life began to turn sour for him. Tyrone's attitude to the prison of the past is to escape it through drink, which is the same attitude Jamie has. Even Jamie, the most cynical character in the play, had talent and enthusiasm once. It was he who first encouraged Edmund to take an interest in poetry, and he can still recite

Of the four characters, only Edmund has a chance of escaping from the prison. The key moment comes in Act 4, when he recalls the mystical experiences he had when he was at sea. These experiences gave him insight into the ultimate reality of life, a peace, joy and unity utterly beyond the normal range of human understanding. Although he has not been able to recapture those moments, he is resolved to try, in his creative work, to express them. As he says to his father, he will never a real poet: I couldn't touch what I tried to tell you just now. I just stammered. That's the best I'll ever do. . Well, it will be faithful realism, at least. Stammering is the native eloquence of us fog people. Edmund is aware of his limitations, but he is committed to making the effort to faithfully record the reality of things as he experiences them, even though he knows he will never feel at home in life and "must always be a little in love with death. " It is, in his own way, a heroic stance. Edmund is committed to the future, to escaping the prison of the past.

MARY I'm not blaming you, dear. How can you help it? How can any one of us forget? (1. 1. 228) Thought: Mary's argument here is that Edmund can't be blamed for being suspicious of Mary, since the past cannot be forgotten. See the quotes on "Fate and Free Will" for more on the past's influence on the present.

MARY Bitterly. Because he's always sneering at someone else, always looking for. . . the worst weakness in everyone. Then, with a strange, abrupt change to a detached, impersonal tone. But I suppose life has made him like that, and he can't help it. None of us can help the things life has done to us. They're done before you realize it, and once they're done they make you do other things until at last everything comes between you and what you'd like to be, and you've lost your true self forever. (2. 1. 76) Thought: Once again, under the influence of morphine, Mary abandons the blame game, recognizing that getting mad at Jamie logically leads to her blaming herself for poor decisions she made in her past (such as, perhaps, marrying James or having Edmund). That's why she

JAMES Mary! Can't you forget–? MARY With detached pity. No, dear. But I forgive. I always forgive you. So don't look so guilty. (3. 1. 73 -74) Thought: This is an unusual moment for James, asking for the past to be forgotten, though it makes sense considering what a jerk he was during their honeymoon. What stands out even more, though, is Mary's claim that she remembers but forgives all of James's wrongdoing. Is this really true? It seems to us that perhaps Mary can explain James's behavior, but she never really stops feeling resentful toward him.

Long day's journey into night dramatist

Long day's journey into night dramatist Theme of forgiveness in long day's journey into night

Theme of forgiveness in long day's journey into night Tall + short h

Tall + short h Once upon a time there lived a little country girl

Once upon a time there lived a little country girl Those who were eager for war with britain

Those who were eager for war with britain A long and carefully organized journey

A long and carefully organized journey It is a long narrative poem of heroes and heroic journey

It is a long narrative poem of heroes and heroic journey Can i see you for a second figurative language

Can i see you for a second figurative language The metal twisted like a ribbon is an example of

The metal twisted like a ribbon is an example of A flag wags like a fishhook there in the sky

A flag wags like a fishhook there in the sky Your face is killing me figurative language

Your face is killing me figurative language Ravenous and savage from its long polar journey

Ravenous and savage from its long polar journey I could sleep forever figurative language

I could sleep forever figurative language Journey into discipleship

Journey into discipleship Dave barry a journey into my colon

Dave barry a journey into my colon Fire in night by elie wiesel

Fire in night by elie wiesel Silent night holy night all is calm

Silent night holy night all is calm Night of the long knives cartoon

Night of the long knives cartoon Cartoon by david low 1933

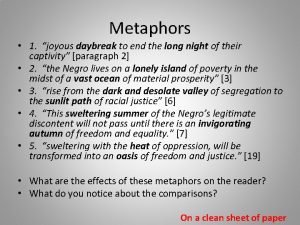

Cartoon by david low 1933 Joyous daybreak to end the long night

Joyous daybreak to end the long night Do not go gentle into that good night poem analysis

Do not go gentle into that good night poem analysis Do not go gentle into that good night wallpaper

Do not go gentle into that good night wallpaper Hyperbole in do not go gentle into that good night

Hyperbole in do not go gentle into that good night Do not go gentle into that good night paraphrase

Do not go gentle into that good night paraphrase Do not go gentle into that good night metaphors

Do not go gentle into that good night metaphors Do not go gentle into that good night nazi

Do not go gentle into that good night nazi Not so long ago people

Not so long ago people Once upon a king and a queen

Once upon a king and a queen Props of tinikling

Props of tinikling Once upon a time long long ago

Once upon a time long long ago Long long int c

Long long int c