Criminal Justice Educators Association of New York State

- Slides: 31

Criminal Justice Educators Association of New York State 2019 Annual Meeting October 24, 2019 Prison Privatization: The Many Facets of a Controversial Industry Dr. Byron E. Price Medgar Evers College--CUNY

§ Private jails, prisons, and detention centers have a long History of Private Prisons history in the U. S. , as far back as 1852 when San Quentin was the first for-profit prison in the U. S. , long before it was state-owned. § A resurgence in private prisons came in the wake of widespread privatization that took place during the 1980 s. § Prior to the 1980 s, some aspects of prison management had been privatized (services), but overall management had still been held by federal and state authorities.

§ Prisons had been privatized before. Louisiana first privatized its penitentiary in 1844, just nine years after it opened. § The company, Mc. Hatton, Pratt, and Ward ran it as a factory, using inmates to produce cheap clothes for enslaved people. History of Private Prisons § One prisoner wrote in his memoir that, as soon as the prison was privatized, his jailers “laid aside all objects of reformation and re-instated the most cruel tyranny, to eke out the dollar and cents of human misery. ” § Much like Core. Civic’s shareholder reports today, Louisiana’s annual penitentiary reports from the time give no information about prison violence, rehabilitation efforts, or anything about security. Instead, they deal almost exclusively with the profitability of the prison.

§ Like private prisons today, profit rather than rehabilitation was the guiding principle of early penitentiaries throughout the South. § “If a profit of several thousand dollars can be made on the History of Private Prisons labor of twenty slaves, ” posited the Telegraph and Texas Register in the mid-19 th century, “why may not a similar profit be made on the labor of twenty convicts? ” § The head of a Texas jail suggested the state open a penitentiary as an instrument of Southern industrialization, allowing the state to push against the “over-grown monopolies” of the North. § Five years after Texas opened its first penitentiary, it was the state’s largest factory. § It quickly became the main Southern supplier of textiles west of the Mississippi.

§ Prison privatization accelerated after the Civil War. § The reason for turning penitentiaries over to companies History of Private Prisons was similar to states’ justifications for using private prisons today: prison populations were soaring, and they couldn’t afford to run their penitentiaries themselves. § The 13 th amendment had abolished slavery “except as punishment for a crime” so, until the early 20 th century, Southern prisoners were kept on private plantations and on company-run labor camps where they laid railroad tracks, built levees, and mined coal.

§ Former slaveholders built empires that were bigger than those of most slave owners before the war. History of Private Prisons § Nathan Bedford Forrest, first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, controlled all convicts in Mississippi for a period. § US Steel, the world’s first billion-dollar company, forced thousands of prisoners to slave in its coal mines.

§ Lessees went to extreme lengths to extract profits. § In 1871, Tennessee lessee Thomas O’Conner forced History of Private Prisons convicts to work in mines and went as far as collecting their urine to sell to local tanneries. § When they died from exhaustion or disease, he sold their bodies to the Medical School at Nashville for students to practice on.

§ Lessees gave a cut of the profits to the states, ensuring that the system would endure. History of Private Prisons § Between 1880 and 1904, Alabama’s profits from leasing state convicts made up 10 percent of the state’s budget. § By 1886 the US commissioner of labor reported that, where leasing was practiced, the average revenues were nearly four times the cost of running prisons.

§ Writer George Washington Cable, in an 1885 analysis of History of Private Prisons convict leasing, wrote the system “springs primarily from the idea that the possession of a convict’s person is an opportunity for the State to make money; that the amount to be made is whatever can be wrung from him…and that, without regard to moral or mortal consequences, the penitentiary whose annual report shows the largest cash balance paid into the State’s treasury is the best penitentiary. ”

§ This maniacal drive for profits managed to create a system that was more deadly than slavery. § Between 1870 and 1901, some three thousand Louisiana History of Private Prisons convicts, most of whom were black, died under the lease of a man named Samuel Lawrence James. § Before the Civil War, only a handful of planters owned more than a thousand convicts, and there is no record of anyone allowing three thousand valuable human chattel to die.

§ Throughout the South, annual convict death rates ranged from 16 percent to 25 percent, a mortality rate that would rival the Soviet gulags to come. § There was simply no incentive for lessees to avoid History of Private Prisons working people to death. § In 1883, one Southern man told the National Conference of Charities and Correction: “Before the war, we owned the negroes. § If a man had a good negro, he could afford to take care of him: if he was sick get a doctor…But these convicts: we don’t own ‘em. One dies, get another. ”

§ States became jealous of the profits private companies History of Private Prisons were making, so in the early 20 th century, they bought plantations of their own and eventually stopped leasing to private companies. § Ten years after abolishing convict leasing, Mississippi was making $600, 000 ($14. 7 million in 2018 dollars) from prison labor. § It was in this world that a man named Terrell Don Hutto would learn how to run a prison as a business.

§ In combination with an overall privatization push by President Reagan, prison populations soared during the "war on drugs" and prison overcrowding and rising costs became a contentious political issue. Why Private Jails Became an Attractive Option § Private business stepped in to offer a solution, and the era of privately run prisons began. § Privately run prisons promised increased, business-like efficiency, which would result in cost savings and an overall decrease in the amount that government would have to spend on the prison system while still provided the same service.

§ It was also theorized that privately run prisons would be held more accountable, because they could be fined or fired, unlike traditional prisons (although the counter point is that privately run prisons are not subject to the same constitutional constraints that state-run prisons are). § The rights of inmates include the following: § The right to humane facilities and conditions Why Private Jails Became Attractive § The right to be free from sexual crimes § The right to be free from racial segregation § The right to express condition complaints § The right to assert their rights under the Americans with Disabilities Act § The right to medical care and attention as needed § The right to appropriate mental health care § The right to a hearing if they are to be moved to a mental health facility

§ Private prisons are big business, with annual budgets in the billions, and there are several large players in the private prison business such as Core Civic (formerly known as Corrections Corporation of America), the GEO Group (formerly known as Wackenhut Securities). Major Players in the Private Jail Business § Corrections Corporation of America alone owns more than 65 correctional facilities in the U. S. and houses over 100, 000 inmates. § Before founding the Corrections Corporation of America, a $1. 8 billion private prison corporation now known as Core. Civic, Terrell Don Hutto ran a cotton plantation the size of Manhattan. § There, mostly black convicts were forced to pick cotton from dawn to dusk for no pay. It was 1967 and the Beatles’ “All you need is love” was a hit, but the men in the fields sang songs with lyrics like “Old Master don’t you whip me, I’ll give you half a dollar. ” Hutto’s family lived on the plantation and even had a “house boy, ” an unpaid convict who served them.

§ While the benefit provided by privately run jails may not match the rhetoric that came with them in the 1980 s, there have been benefits associated with turning control of prisons over to private companies. The Benefits of Private Jails § In a study conducted by James Blumstein, director of the Health Policy Center at the Vanderbilt Institute for Public Policy Studies, the study found that states that used private prisons could save up to $15 million a year. § The U. S. Department of Justice's National Institute of Justice found that private prisons had a higher quality of services than traditional prisons.

§ One of the most perverse incentives in a privately run prison system is that the more prisoners a company houses, the more it gets paid. The Criticisms of Private Jails § This leads to a conflict of interest on the part of privately run prisons where they, in theory, are incentivized to not rehabilitate prisoners. § If private prisons worked to reduce the number of repeat offenders, they would be in effect reducing the supply of profit-producing inmates.

§ While some studies have demonstrated that private prisons may save governments money, other studies have found just the opposite. § A study by the U. S. Bureau of Justice Statistics found no The Criticisms of Private Jails such cost-savings when it compared public and private prisons. § This is in part because simple numbers don't tell the whole story. § For instance, privately run prisons can refuse to accept certain expensive prisoners, and they regularly do. § This has the effect of artificially deflating the costs associated with running a private jail.

§ Core. Civic prisons aren’t nearly as brutal labor camps Criticisms of Private Jails under convict leasing or the early 20 th century state-run plantations, but they still go to grotesque lengths to make a dollar. § Shane Bauer saw this first hand when, in 2014, he went undercover as a prison guard in a Core. Civic prison in Louisiana. § There, he met a man who lost his legs to gangrene after begging for months for medical care.

§ Core. Civic was often resistant to sending prisoners to the hospital: their contract required that outside medical visits be funded by the company. Criticisms of Private Jails § Educational programs were axed to save money. § To keep costs low, guards were paid $9 an hour and oftentimes there were no more than 24 on duty, armed with nothing but radios, to run a prison of more than 1, 500 inmates.

§ The prison was incredibly violent as a result. In a four- Criticisms of Private Jails month period in 2015, the company reported finding some 200 weapons, 23 times more than the state’s maximum security prison. § Shane Bauer knew one inmate who committed suicide after repeatedly going on hunger strike to demand mental health services in a prison with only one part-time psychologist. § When he died, he weighed 71 pounds.

§ According to a 2017 survey by the Prison Policy Initiative Private Prisons and Prison Labor (PPI), of the more than 2. 2 million people incarcerated in state and federal prisons and local jails across the United States, 61 percent hold some form of job. § In marketing materials prepared for Federal Prison Industries, also known as UNICOR, the federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP) invites free world businesses to leverage its “skilled workforce” at “low labor rates” and take advantage of its “cost-effective labor pool. ” § Created in 1934, UNICOR pays prisoners between $0. 23 and $1. 15 an hour.

§ According to the agency’s most recent annual report, Private Prisons and Prison Labor about 17, 000 prisoners in 50 manufacturing centers are paid those low wages to make products ranging from air filters and clothing to office supplies and furniture. § Many of the items produced by UNICOR are purchased by the federal government – the agency had over $502. 8 million in sales in fiscal year 2018. § Since 2011, Congress has also allowed the prison industry program to produce and sell millions of dollars worth of prisoner-manufactured goods to private companies.

§ Even military goods are produced by UNICOR, some of which end up in the hands of foreign governments. Private Prisons and Prison Labor § Billed as a way to prepare prisoners for life after release, as well as a tool to keep U. S. firms from exporting jobs to lower-wage countries, UNICOR’s private-sector work programs have also put it in the calling center business, advertising its prisoner-staffed call centers as one of the “best-kept secrets” in the industry. § In a recent Vox. com article, an unnamed CEO touted the benefits of using prisoner labor.

§ New York State has been leading the way in flexing its New York Becomes First State to Be Rid of Private Prisons muscles with respect to the private prison industry, having taken three concrete actions against private prisons: 1. prohibiting private prisons from operating within the state, § 2. divesting state pension funds from the largest private prison companies, GEO Group and Core. Civic, and then just last week, § 3. passing Bill S 5433 in the State Senate, which would prohibit NY State-chartered banks from “investing in and providing financing to private prisons. ”

§ https: //www. followthemoney. org/research/blog/private- Private Prisons and Lobbying prisons-pour-millions-into-lobbying-state-lawmakers § https: //www. followthemoney. org/research/institutereports/private-prisons-principally-profit-oriented-andpolitically-pliable

§ Since the First Step Act only applies to those held in federal prisons, it didn’t help the nearly 90 percent of the rcerated population in state and local facilities. Private Prisons and the First Step Act § To its credit, the First Step Act includes some modest sentencing reforms that will likely result in the early release of several thousand of the 180, 000 people serving time in federal prisons. § The legislation makes retroactive the Fair Sentencing Act of 2010, which reduced (but did not eliminate) sentencing disparities between crack and powder cocaine.

§ It lowers the penalties for some other drug offenses and softens the federal three-strikes law but does not make these sentencing reforms retroactive. Private Prisons and First Step Act § The measure expands the availability of early-release credits for some prisoners and of compassionate release for those who are gravely ill. § The First Step Act also ameliorates some conditions of confinement by, for example, prohibiting the solitary confinement of juveniles and the shackling of pregnant prisoners.

§ Critics of the First Step Act worry that it could be farreaching in other ways. Private Prisons See the First Step Act as Business Strategy § Some warn of unintended consequences down the line. Implementing the First Step Act will rely on infrastructure that has yet to be built — and which could give opportunities for companies like Core. Civic to expand their business. § Indeed, along with its main competitor, GEO Group, Core. Civic enthusiastically backed the First Step Act.

Private Prisons See the First Step Act as Business Strategy § Both corporations have spent years repositioning themselves from private prison firms to providers of re-entry services — the very kinds of “evidence-based” tools that the legislation repeatedly invokes.

Questions

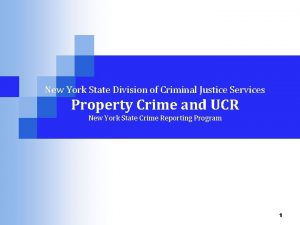

Nys division of criminal justice services

Nys division of criminal justice services New york harm reduction educators

New york harm reduction educators Nurse practitioner association of new york state

Nurse practitioner association of new york state New york state professional firefighters association

New york state professional firefighters association New york state association of transportation engineers

New york state association of transportation engineers New york state amateur hockey association

New york state amateur hockey association New york state county highway superintendents association

New york state county highway superintendents association Sexting laws in ct

Sexting laws in ct Southern connecticut state university criminal justice

Southern connecticut state university criminal justice Professional association of georgia educators

Professional association of georgia educators New york mental health counselors association

New york mental health counselors association Guelph cjpp

Guelph cjpp What are the branches of criminal justice system

What are the branches of criminal justice system Funnel effect criminal justice

Funnel effect criminal justice Grass eater police

Grass eater police Criminal justice lesson

Criminal justice lesson Consensus model criminal justice

Consensus model criminal justice Consensus model criminal justice

Consensus model criminal justice The oldest community-based correctional program is

The oldest community-based correctional program is Four pillars of justice

Four pillars of justice Consensus model criminal justice

Consensus model criminal justice Behavioral theory in criminal justice

Behavioral theory in criminal justice Individual rights

Individual rights Consensus model criminal justice

Consensus model criminal justice Consensus model criminal justice

Consensus model criminal justice Nonintervention perspective of criminal justice

Nonintervention perspective of criminal justice Unit 2 criminal law and juvenile justice

Unit 2 criminal law and juvenile justice Wedding cake model of criminal justice

Wedding cake model of criminal justice Arizona criminal justice information system

Arizona criminal justice information system Responsibilities of saps in the criminal justice system

Responsibilities of saps in the criminal justice system National archive of criminal justice data

National archive of criminal justice data Criminal justice wedding cake diagram

Criminal justice wedding cake diagram