CHAPTER 11 ASSESSMENT OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND SEDENTARY

- Slides: 18

CHAPTER 11 ASSESSMENT OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND SEDENTARY BEHAVIOUR

KEY KNOWLEDGE v Subjective and objective methods of assessing physical activity and sedentary behaviour such as recall surveys or diaries, pedometry, accelerometry, inclinometry, observation tools (including digital tools such as smartphone and tablet apps) and personal activity trackers © Victorian Curriculum & Assessment Authority

WHY MEASURE PHYSICAL ACTIVITY?

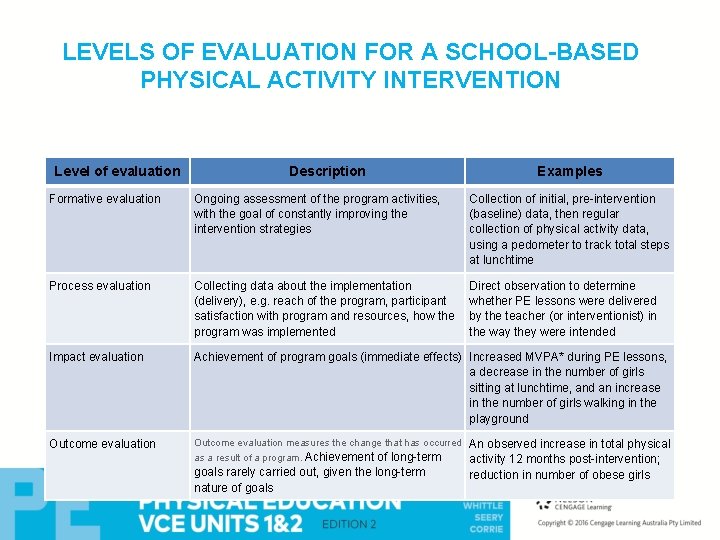

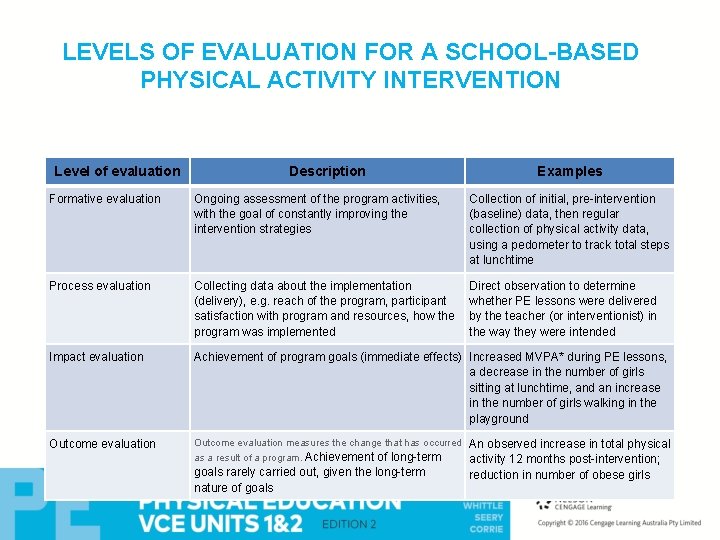

LEVELS OF EVALUATION FOR A SCHOOL-BASED PHYSICAL ACTIVITY INTERVENTION Level of evaluation Description Examples Formative evaluation Ongoing assessment of the program activities, with the goal of constantly improving the intervention strategies Collection of initial, pre-intervention (baseline) data, then regular collection of physical activity data, using a pedometer to track total steps at lunchtime Process evaluation Collecting data about the implementation (delivery), e. g. reach of the program, participant satisfaction with program and resources, how the program was implemented Direct observation to determine whether PE lessons were delivered by the teacher (or interventionist) in the way they were intended Impact evaluation Achievement of program goals (immediate effects) Increased MVPA* during PE lessons, a decrease in the number of girls sitting at lunchtime, and an increase in the number of girls walking in the playground Outcome evaluation measures the change that has occurred as a result of a program. Achievement of long-term goals rarely carried out, given the long-term nature of goals An observed increase in total physical activity 12 months post-intervention; reduction in number of obese girls

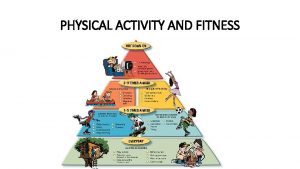

MEASURING THE DIMENSIONS OF PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND SEDENTARY BEHAVIOUR We can measure either one dimension of physical activity and sedentary behaviour or a combination of dimensions. We can measure: v activity type v activity intensity v activity frequency v activity time (duration)

MEASURING ACTIVITY TYPE Reasons for knowing the various types of activity people participate in: v To determine the energy expenditure associated with that particular physical activity by assigning a metabolic equivalent (MET) v To assess how much physical activity is done within each domain (household and gardening, active transport, job or school, and leisure) v To determine the most common activities in particular population subgroups, or within a specific context or setting.

MEASURING ACTIVITY FREQUENCY Frequency refers to the number of physical activity bouts during a specific time period (e. g. per day or per week).

MEASURING ACTIVITY TIME (DURATION) The duration of physical activity and sedentary behaviour simply refers to how long a person is engaged in it. The duration recommended for different population subgroups varies. If an adult was moderately active for 30 minutes a day they would burn approximately 600 k. J a day, or about 4000 k. J a week (equivalent to about 150 k. Cal per day or 1000 per week. ) For other levels of intensity, the time taken to burn this minimum of 600 k. J/ day would vary. For example, it would take only 22 of vigorous intensity exercise to burn 600 k. J.

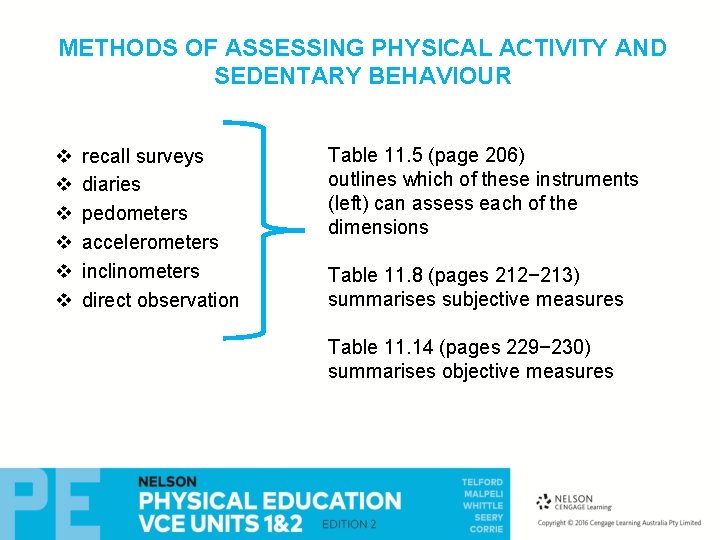

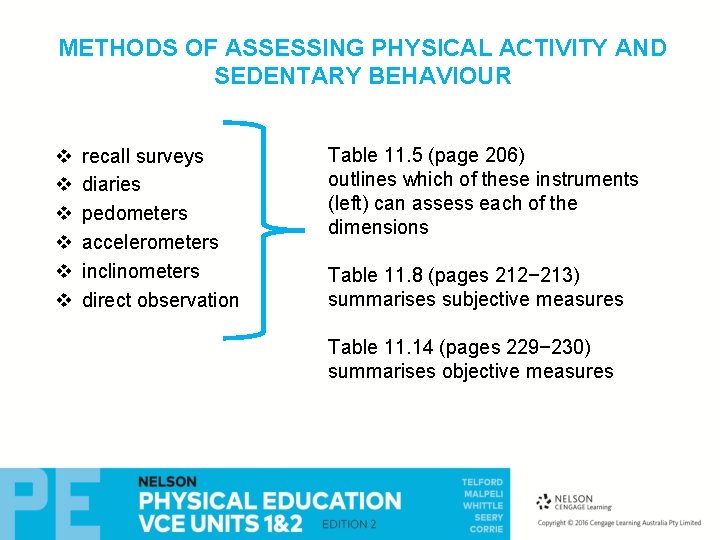

METHODS OF ASSESSING PHYSICAL ACTIVITY AND SEDENTARY BEHAVIOUR v v v recall surveys diaries pedometers accelerometers inclinometers direct observation Table 11. 5 (page 206) outlines which of these instruments (left) can assess each of the dimensions Table 11. 8 (pages 212− 213) summarises subjective measures Table 11. 14 (pages 229− 230) summarises objective measures

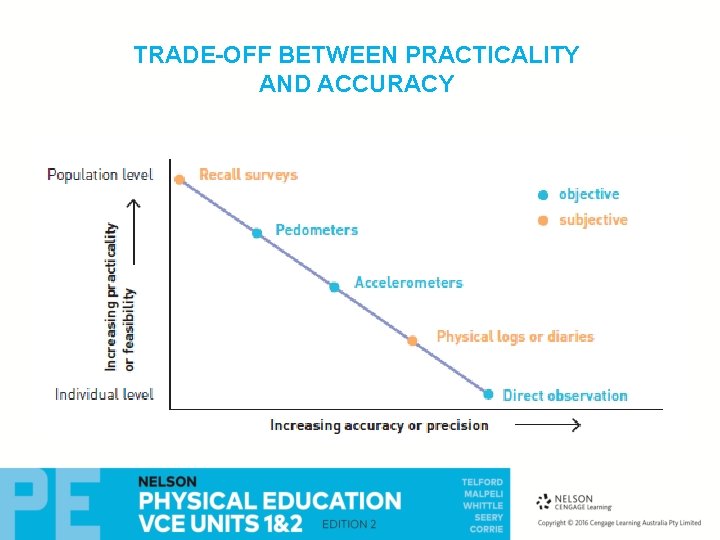

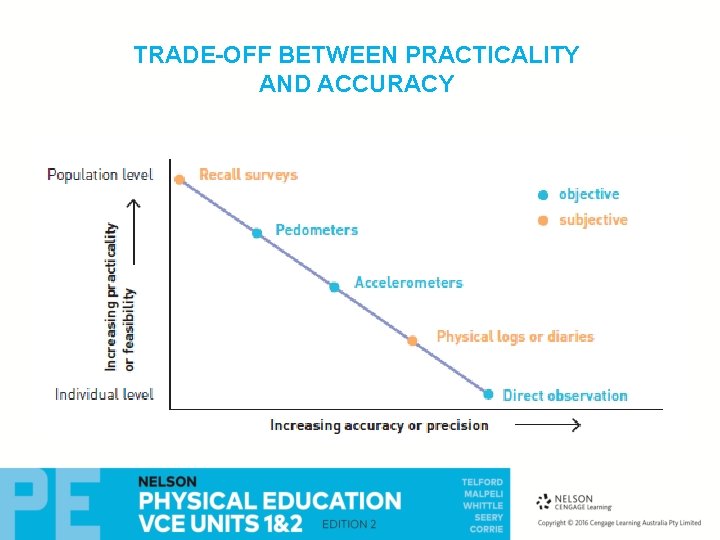

TRADE-OFF BETWEEN PRACTICALITY AND ACCURACY

SUBJECTIVE MEASURES (1) These include recall surveys and diaries. Advantages v Can capture both quantitative and qualitative information v Can be administered quickly and easily v Cost-effective for large-scale studies v Usually low burden on participants v Can predict energy expenditure from daily physical activities when compared to the Compendium of Physical Activities (see Table 11. 6, page 207)

SUBJECTIVE MEASURES (2) Disadvantages v Not suitable for assessing children under age 10 or very old adults, due to cognitive limitations v Reliability and validity problems associated with over-reporting due to social desirability bias, memory limitations or misinterpretation of physical activities in different populations v Interviewer may be needed to obtain accurate data

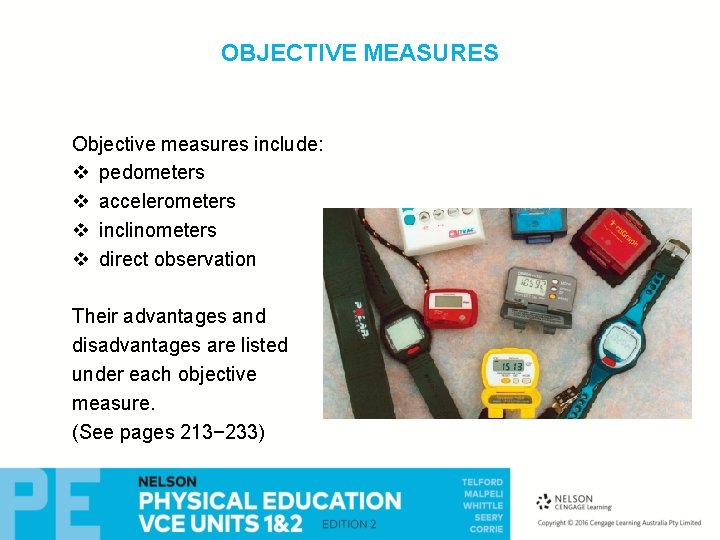

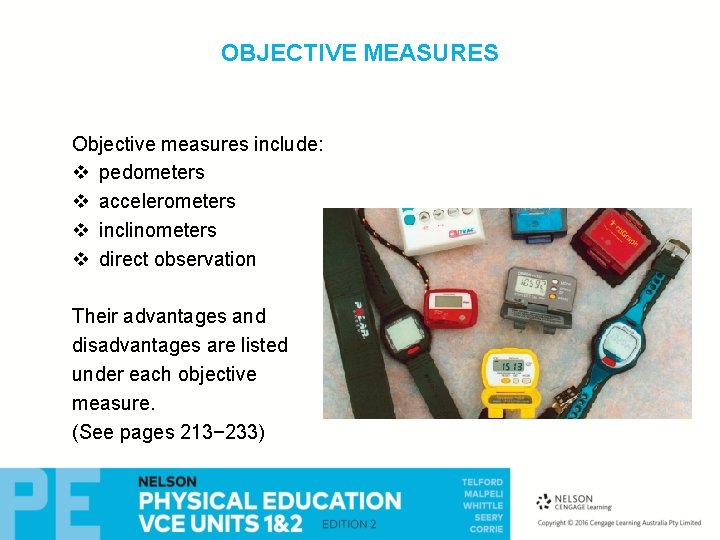

OBJECTIVE MEASURES Objective measures include: v pedometers v accelerometers v inclinometers v direct observation Their advantages and disadvantages are listed under each objective measure. (See pages 213− 233)

MEASURING SEDENTARY BEHAVIOUR (1) The main objective measures for assessing sedentary behaviour are accelerometers, inclinometers, direct observation and devices. Accelerometers can detect low-intensity or sedentary behaviour using movement counts or g-forces below a certain threshold, although there is little difference in standing and sitting data, despite a difference in energy expenditure. Inclinometers are electronic devices that can differentiate between standing and sitting. Although traditionally used in construction and vehicle stability testing, some can be worn on a person’s thigh to measure the amount of time they spend sitting. While you can be considered sedentary when you are standing, the health consequences associated with sitting for many hours are worse than long hours spent standing.

MEASURING SEDENTARY BEHAVIOUR (2) Direct observation can assess sedentary behaviour. It is useful in school or workplace settings, but is not very practical for use in people’s homes. Devices can also be fitted to computer or television screens to measure usage and viewing time. However, these are rarely used in sedentary behaviour research. (A television being on doesn’t mean anyone is watching it. Similarly, we cannot assume that a person watching television is sedentary – they might also be working out on a treadmill, elliptical machine or stationary bicycle. )

SELECTING YOUR ASSESSMENT TOOL v Not all measures are suitable for use with particular population subgroups. v Cognitive and memory limitations may restrict use of particular subjective measures with certain groups v Table 11. 15 (pages 230− 231) summarises suitability of the various measurement options for a range of sub-groups.

Sedentary farmer hypothesis

Sedentary farmer hypothesis Arthropoda

Arthropoda Breakfast for a sedentary worker

Breakfast for a sedentary worker Reducible hernia

Reducible hernia What is physical fitness test in mapeh

What is physical fitness test in mapeh Fitness chapter 12

Fitness chapter 12 Chapter 12 lesson 1 benefits of physical activity

Chapter 12 lesson 1 benefits of physical activity Chapter 4 physical activity for life answers

Chapter 4 physical activity for life answers Chapter 12 lesson 3 planning a personal activity program

Chapter 12 lesson 3 planning a personal activity program Fitness chap 3

Fitness chap 3 Chapter 13 physical assessment

Chapter 13 physical assessment Debye huckel equation

Debye huckel equation Who global strategy on diet, physical activity and health

Who global strategy on diet, physical activity and health Ocr level 3 sport and physical activity

Ocr level 3 sport and physical activity History of physical activity teaches us about

History of physical activity teaches us about Definition of sport pedagogy

Definition of sport pedagogy Physical activity and nutrition coordinator

Physical activity and nutrition coordinator Safe and smart physical activity

Safe and smart physical activity Chapter 2 classroom activity 2-2

Chapter 2 classroom activity 2-2