A Not So Silent Night From corpse to

- Slides: 8

A Not So Silent Night From corpse to corpus: resurrecting indigenous languages Lourdes Trammell, MA, Applied Linguistics

Principles of living language CONTEXTUAL RETRANSLATION

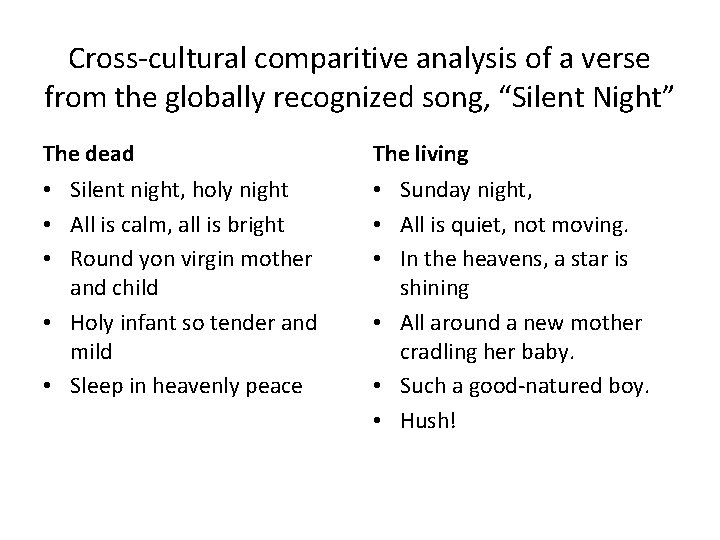

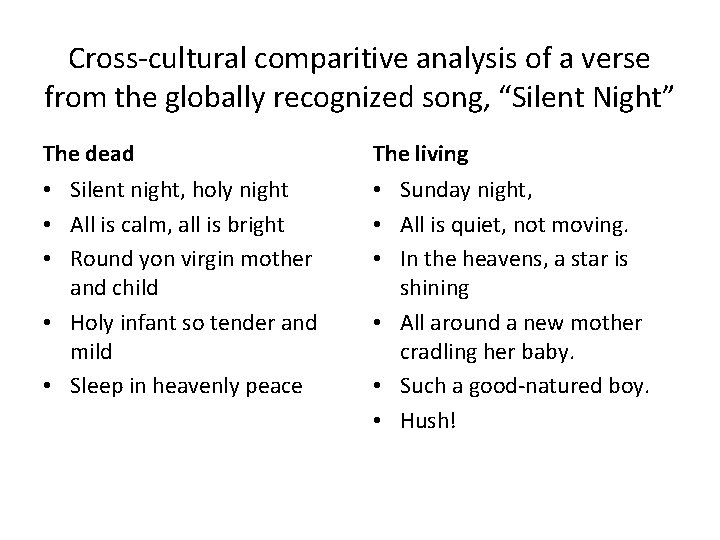

Cross-cultural comparitive analysis of a verse from the globally recognized song, “Silent Night” The dead The living • Silent night, holy night • All is calm, all is bright • Round yon virgin mother and child • Holy infant so tender and mild • Sleep in heavenly peace • Sunday night, • All is quiet, not moving. • In the heavens, a star is shining • All around a new mother cradling her baby. • Such a good-natured boy. • Hush!

Principles of living language • • Human language is an emergent phenomenon that depends on the transformation of human cognitive functions through socialization. That is to say, language is not “hard-wired”, as Chomsky and Pinker asserted, nor is it inherited through some primordial gene that manifests under the right conditions. Nor is it comprised of universal signs embedded in the mind that represent instincts and simply manifest meaning with the right triggers and readers, like unzipped software uploaded from some collective unconscious database (Jung et al). The cognitive substrates of language include, minimally, the sensory-motor cortex and sensory-motor functions, the linguistic centers in the brain that register and parse rhythm, sequence and syntax, and neuronal ability to synchronize and synthesize sensory input into realization. Then, there’s thought, executive function, judgment, pursuit and inhibition impulses, and the human propensity for active, directed, and intuitive learning. Underneath it all, there is consciousness, itself, as a platform. In actuality, human language engages the entire organism, as a form of response, as unconscious reflex, and as an instinct for communication and meaning. It is a global act of the organism. That linguistic functions and instincts can be impaired, even irreparably, evidences the need for ongoing interaction as an essential requirement for language acquisition and development. Language is a matrix comprised of scaffolding that continues to infinity, a spiraling tower of Babylon – but one that endures long after any individual or any civilization expires. • • Language, hence, is not a corpse, a mummified vestige destined for a museum display case, but a corpus representative of a living system. Language is analogous to a coral reef, which, built by living organisms, eternally sustains entire ecosystems , depending on, emerging and evolving as it does from the byproducts of the living and the dying of its builders and those who acquire it and thrive on its systemic benefits. Coral is not an instinct of organisms. Coral is not triggered by some random genetic mutation. Coral is not a dormant allele waiting for the right conditions. Coral is a living, ever-amalgamating organism, created through organic synthesis and shaped by continuous interaction of forces and life-forms, existence, death and decay. Cut the living coral and the reef dies. So it is with language, a virtual living coral reef, a permanent and monumental amalgamated tribute to the lives and deaths of countless individual members of the human species, known and unknown, indeed, a tribute to the entire universe. Wherever humans go, whatever they see or imagine, you see, they talk about it. Wherever there is language, there is another bead in another segment added to another bed and to the reef, overall. Modern translations of indigenous languages, done with the intent to revitalize through preservation, are slicing into living reefs, causing death by vivisection because linguists aren’t trained to perceive language as a living organism within a vital ecosystem. They’re trained to look only at the little bits, the beads, the beds, the petrified remains of papyrus and mud tablets. Everything else is “subjective” and therefore, dismissed. This exercise is intended to grow new coral, to infuse languages with new oxygen through cultural retranslation, to resurrect, not preserve, language, which was never meant to be an artifact, in the first place.

Principles of living language • • The so-called universal grammars “embedded” in language that supposedly represent “instincts” through symbolism and can be “triggered” or “decoded” by proper framing and interpretation have a certain mystic appeal and often, these same sentiments are expressed by speakers of many indigenous languages, themselves. These ideas are a common enough expression of the perception of language as magical, baffling and powerful. Like consciousness, language is a thing we acquire and use without being able to fully understand its origins, or even its purpose. It’s a thing that eludes empirical examination, even as it is being used to conduct such examinations. For Vygotsky, it’s a tool man shapes that in turn shapes man, and that is the fundamental principle of our linguistic coral reef. If we examine language in practice, however, we examine, by necessity, consciousness and identity in practice, as well, and these are integrated components that too many modern linguists mistakenly seek to slice away in order to produce “viable” transcriptions and translations, laying the flesh aside and bleeding the corpus dry to expose the bones and nerves and pieces and parts, reassembling them in plaster molds like paleoarchaeologists and declaring, “Ha! A linguistic reconstruction! Just as good as the original but you can take it apart easier!” (once the annoying living speakers have been eliminated). Linguists need to work with the living, not the dead. Languages, even the bone dry reefs of ancient languages, are capable of being revitalized and resurrected, still having the potential to live and develop, and therefore, need to be approached as living systems, not as inanimate artifacts. Language exists as a corpus, not a corpse, in other words, and thrives as such unless vivisected through linguistic analysis seeking to preserve for the archives something that’s still alive. • • And the elements of living language systems include all of the things erroneously mistaken for their origins: symbols, instincts, grammars, mimicry, negative feedback, response and reflex, interpretation, translation and especially misunderstanding, the analog of random mutation and forces of selection that keeps thing original and interesting and defines shift and standardization, pidgin, creole, orthographies, dialect , accent, register, disorder, dysfunction, and ultimately discourse, itself. This original exercise in applied linguistics, “Contextual Retranslation: A Not So Silent Night”, was designed and presented as a component of a professional development workshop for issues in translation and field research for The University of Arizona’s AILDI summer program in 2000, under the supervision of Dr. José-Antonio Flores Farfán. It involves eliciting cultural translations that encompass the broadest and deepest degrees of comprehension, including literal translation, possible and impossible conceptualization and compensations, cultural transposition of meaning, and interpretation with validity checks by consensus. It also engenders subject development of gloss and etymology for target languages among native speakers. These are works done by subject speakers, not of or about or with or to subject speakers, producing an authentic, self-generated account of living language by living speakers, actively engaged in communication with nonindigenous speakers. In short, this exercise assists those native speakers of indigenous languages who need and/or want to be understood by non-native speakers in a way that is mutually comprehensible and adequate for continuing discourse at personal, social, cultural, professional and academic levels. In this exercise, the researcher can participate alongside subjects and contribute cultural context to, but not govern, the translation.

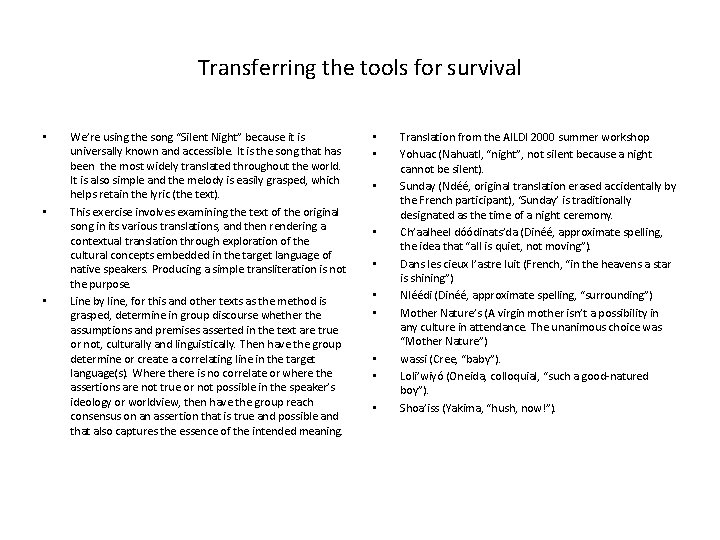

Transferring the tools for survival • • • We’re using the song “Silent Night” because it is universally known and accessible. It is the song that has been the most widely translated throughout the world. It is also simple and the melody is easily grasped, which helps retain the lyric (the text). This exercise involves examining the text of the original song in its various translations, and then rendering a contextual translation through exploration of the cultural concepts embedded in the target language of native speakers. Producing a simple transliteration is not the purpose. Line by line, for this and other texts as the method is grasped, determine in group discourse whether the assumptions and premises asserted in the text are true or not, culturally and linguistically. Then have the group determine or create a correlating line in the target language(s). Where there is no correlate or where the assertions are not true or not possible in the speaker’s ideology or worldview, then have the group reach consensus on an assertion that is true and possible and that also captures the essence of the intended meaning. • • • Translation from the AILDI 2000 summer workshop Yohuac (Nahuatl, “night”, not silent because a night cannot be silent). Sunday (Ndéé, original translation erased accidentally by the French participant), ‘Sunday’ is traditionally designated as the time of a night ceremony. Ch’aalheel dóódinats’da (Dinéé, approximate spelling, the idea that “all is quiet, not moving”). Dans les cieux l’astre luit (French, “in the heavens a star is shining”) Nléédi (Dinéé, approximate spelling, “surrounding”) Mother Nature’s (A virgin mother isn’t a possibility in any culture in attendance. The unanimous choice was “Mother Nature”) wassi (Cree, “baby”). Loli’wiyó (Oneida, colloquial, “such a good-natured boy”). Shoa’iss (Yakima, “hush, now!”).

Analysis • • In analysis, we have a multi-cultural translation of a wellknown song. Although some literal translations were given from French and Dinéé (“in the heavens a star is shining” is directly from the French version of the song, and “all is calm” and “’round yon” yield literal translations of phrases into Dinéé), the rest remained subject to interpretation, where cultural context dictated the choices. A silent night, a holy night and a virgin mother were “not true”, and “sleep in heavenly peace” had no cognate, and so, these were interpreted based on context, appropriateness and sensibility. The purpose is not to render a poetic interpretation, yet, this multi-cultural translation is far more immediate, hushed and poignant than the original or its missionary-informed translations and still retains the essential content of the text. What’s interesting is that in the standard version of this song in Dinéé, the line “all is bright” is “ch’aalheel adindiin” (“darkness bright”), an acceptable contradiction , and “noisy bright night” in Nahuatl is likewise acceptable. In both cultures, darkness or nighttime is normally full of sound and brightness. We see in this method how cultural context is reflected as worldview, what is true or possible, and what is untrue or impossible, and the values each are ascribed. Again, in no indigenous culture represented was the concept “virgin mother” allowable or translatable. This was a universal impossibility. • • A simple task such as this, with such a simple song as this, proves to be far more complex and rewarding, in the final analysis. In teaching this translation method, many opportunities arise for an enriched discussion of cultural values, as well as for consensus-reaching. The participants in this workshop were able to engage in critical metadiscourse with other indigenous peoples, and were astonished at how different they all were, and how yet each participant was afforded the opportunity for an equal contribution. When the translation was done, they all read it together out loud and when they came to the last line, because the translation was culturally meaningful to each of them all the way through, they spontaneously said “Shhhhh…” This was the logical conclusion to the birth of any child, in all their disparate cultures. They ended on a universal reflex, in other words, which is, ironically, an action without a word. The shared expression was the signifier that they had “gotten it right”, that everyone’s voice had been included to everyone’s mutual satisfaction.

Conclusions • • Academically, perhaps the most beneficial result was that the participants had a tool they could finally use with competence and they began applying it to their work in translation, completing substantial work in their last week, including a full Yakima gloss with IPA transcription and dialectic variations. Translation was not so far beyond them any more, and with a little exercise, they gained the principles and the confidence they needed to succeed. The value of determining truth and non-truth according to cultural context and the practice of examining these contexts critically through linguistic application opened the doors for them. Only two of the participants were college-educated. The rest were elders and administrators or appointed by their home councils to attend the workshop for efforts in language preservation and revitalization. They were able to return with an exercise they could apply with their students and the skills they needed to speak of their own languages in competent metadiscourse (with metalinguistic competency). Most importantly, they could demonstrate what they had discovered in a practical and effective manner. • • • Roman Jakobson said that the code and the context, indeed, all aspects of language, carry cultural meaning, and that an utterance could contain the entirety of an individual’s worldview. The trick was learning how to crack the code. Charles Briggs said that good field research preserved the culture of the speaker, as well as the language. The trick was learning how to ask. José-Antonio Flores Farfán said that translations should be done by native speakers and delivered to linguists in field research. The trick was getting them the right tools for the job. The participants in his workshop said that they knew what was needed. The trick was finding new ways to use old tools – their own languages. Finding new ways to use old tools is the secret to revitalization and resurrection of culture and language and indeed defines their very character.