THE SCARLET LETTER 2 MEN RESISTING Hester Prynne

- Slides: 14

THE SCARLET LETTER (2)

MEN RESISTING Hester Prynne is the very heart of The Scarlet Letter (it is her story that, in «The Custom. House, » Jonathan Pue orders Hawthorne to tell), but she is not the only main character of the romance. The 24 chapter of the book are almost evenly distributed among four characters – Hester, her daughter Pearl, her lover Arthur Dimmesdale, and her husband Roger Chillingworth. The two male co-protagonists, and other male characters as well, are the forces who resist Hester’s attempts of selfdetermination, in one way or another (while Pearl is the subject who must build up her own identity against the ways in which not only the

THE NAME OF THE FATHER The letter «A» designates Hester, but also her accomplice, Arthur Dimmesdale. If Hester is viewed by the community as a sinner woman, a new «Eve» (a book by Leila Leah Bronner on the female characters of the Bible is titled From Eve to Esther: Rabbinic Reconstructions of Biblical Women), her lover can be considered a new «Adam. » But Arthur is also a father: he is of course Pearl’s father, but he is also a (young) father of the Church – a «new Abraham. » If Hester resists patriarchal power, and refuses to say the name of the father (in Lacanian thinking, by the way, the name of the father is the metaphor of patriarchal power, of the superego), Arthur forces Hester to stay alone by not confessing the truth, and makes her bring the whole burden of their crime. He resists Hester’s will to freedom by keeping silent – the reverse of Hester’s silence, which keeps him free (even if some critics, like Leland Person in «Hester’s Revenge, » think it to be what keeps him imprisoned in his hypocrisy, forgetting the simple thing that nobody actually forces him to hid the

FATHERS AND SONS Arthur’s self is deeply divided between his being a father and his being a son – Abraham and Adam – and his public and private selves. In public he is a fatherly figure of authority in his position of parson, but his private identity as Pearl’s father is not revealed until (maybe) the end. In private, he is feeble and weak-willed, and subject to the stronger power of a substitute (and malign) father, Roger Chillingworth, and of a «masculine» woman such as Hester. Both in the scene in the forest and in the scene of his death he behaves like a frightened son who wants to be reassured by his lover/mother – on the scaffold, the image of him in Hester’s arms resembles that of the Pietà. But by finally representing himself as a dying son who is also «the one sinner of the world» he manages to become transfigured as the Son who takes upon himself all the sins of humankind – as a

TELLING, NOT TELLING Arthur is the embodiment male Puritan hypocrisy (vs. Hester’s female silence). He seems to repeatedly tell the truth about his sin, but he perfectly but his «confessions» are interpreted in exactly the opposite way. In his sermons «more than a hundred times» he tells «his hearers that he was altogether vile, a viler companion of the vilest, the worst of sinners, a thing of abominable iniquity» – but: «They heard it all, and did but reverence him the more, » and Dimmesdale «well knew – subtle, but remorseful hypocrite that he was! – the light in which his vague confessions would be viewed. » His hyprocrisy turns him into a living oxymoron, the conflation of truth and falsehood (which will culminate in his final «triumphant ignominy» ): «He had spoken the very truth, and transformed it into the veriest falsehood. And yet, by the constitution of his nature, he loved the truth, as few men ever did. Therefore, above all, he loathed his miserable

AMERICAN VAMPIRE In the «love triangle» of The Scarlet Letter, which should reproduce the original triangle Adam-Eve-Satan, Satan should be Roger Chillingworth, a character systematically represented as demonic. But instead of being the tempter, and being the betrayed husband, Chillingworth is the «victim of the victims» of temptation, Hester and Arthur. More than someone who tempts someone else, Chillingworth is someone who thrives on the life of somoene else – he is one of the first American vampires (the very first being the protagonist of «The Black Vampyre: A Legend of St. Domingo» (1819) by Uriah Derick D'Arcy (pseudonym of Richard Varick Dey). In the title of the two chapters devoted to him he is called «Leech, » (meaning «doctor, » but also «bloodsucker. » His victim is of course Arthur, whom he should cure, but whom he instead transforms into a sort of living dead. Their relationship also takes homosexual undertones, when the two men start living in the same house, but this must not be understood in sexual terms: what matters here is gender, because the two create a totally male union

THE FIRST AMERICAN Pearl is mythically the first American-born character in American literature – and she is a girl. In a sort of «resistance» to American dominant patriarchal culture, Hawthorne does not only create the strongest of all female characters – he also gives her a daughter who will be the last one standing, at the end of the romance, and will get rich and happy by coming back to Europe, in a mirror reverse image of Puritan migration. Pearl is also the very heart of the romance, because she is the living sign mirroring the artificial sign of the scarlet A ( «It was the scarlet letter in another form; the scarlet letter endowed with life!» ) – both meaning the sin of adultery and both supplementing that meaning by becoming much more. Pearl thus becomes the embodiment of the romance, and like the romance she is «not amenable to rules. » And Pearl is a mystery, because she constantly signals the void which is the narrative «engine» of the plot – the absence of her father, who does not recognize her as his daughter – that is, the absence of her own origins – that is, the absence (or one of the absences) which is at the center of American history, the absence of the recognition of the role of the female subject

MOTHER VS. DAUGHTER Even more than his mother, Pearl is the embodiment of the resistance to power – she is almost an antinomian. Chillingworth and Dimmesdale comment that she has the «freedom of a broken law, » and no «reverence for authority, no regard for human ordinance or opinions, right or wrong. » Even Hester is an authorty Pearl resists, because the mother totally identifies the daughter with the scarlet letter, as the whole Boston does: «The mother herself – as if the red ignominy were so deeply scorched into her brain, that all her conceptions assumed its form – had carefully wrought out the similitude; lavishing many hours of morbid ingenuity, to create an analogy between the object of her affection, and the emblem of her guilt and torture. » Hester tries to integrate her daughter in the community: at the age of three, Pearl «could have borne a fair examination in the New England Primer, or the first column of the Westminster Catechism, » taught to her by her mother. But just as she supplements the scarlet letter with her art, so Hester does with Pearl, leaving «imaginative faculty its full play in the arrangement and decoration of the dresses which the child wore, » with «the richest tissues that could be procured. » The result is that Pearl is much more than one child: «Pearl’s aspect was imbued with a spell of infinite variety; in this one child there were many children, comprehending the full scope between the wild-flower prettiness of a peasant-baby, and the pomp, in little, of an infant princess. » Hester also transmits her own «warfare spirit» to Pearl, who resists any «kind of discipline» and replies with a definat (like her mother’s) gaze which is «so intelligent, yet inexplicable, so perverse,

THE FIRST DETECTIVE Being the object of obsessive inquiries about her identity, Pearl soon learns how to investigate her origins – she is, mythically, the first American detective. She especially asks about that «Black Man» (Arthur always wears black) who could be her father and whose mark could be the scarlet letter itself. She rapidly becomes a totally autonomous seacher of truth, equipped with «an unflinching courage, – an uncontrollable will, – a sturdy pride, which may be disciplined into self-respect, – and a bitter scorn of many things, which, when examined, might be found to have the taint of falsehood in them. » And of course she makes the right questions: «What does the letter mean, mother? – and why dost thou wear it? – and why does the minister keep his hand over his heart? »

RESISTING WHOM? The force Hester and Pearl resist is that of Puritan patriarchal power, only imperfectly embodied by Dimmesdale (who is also its victim) and partially by Hester herself in her trying to «control» her daughter. The supreme representative of Puritan authority in The Scarlet Letter is Richard Bellingham. But besides having being involved in a sexual scandal himself, Bellingham’s hypocrisy (mirroring Dimmesdale’s) is also evident in how he organizes his mansion: instead of a modest house, befitting the Puritan ideology of austerity, his house resembles «Aladdin’s palace, » and instead of celebrating the «new, » it constantly reminds the (English) past, as if «the whole being of the Elizabethan age, or perhaps earlier, and heirlooms, transferred hither from the Governor’s paternal home» together with «a row of portraits, representing the forefathers of the Bellingham lineage. » When Hester goes there to be interviewed, she is welcomed «by one of the Governor’s bond-servants; a free-born Englishman, but now a seven-years’ slave. During that term he was to be the property of his master, and as much a commodity of bargain and sale as an ox, or a joint-stool. The serf wore the blue coat, which was the customary garb of serving-men at that period, and long before, in the old hereditary halls of England. » What the Puritans are establishing in America, and what Hester and Pearl resist, is the repetition of the old system of power (and a new system of exploitation – that of slavery…) – and their resistance is mirrored in the Governor’s garden: «the proprietor appeared already to have relinquished, as hopeless, the effort to perpetuate on this side of the Atlantic, in a hard soil and amid the close struggle for subsistence, the native English taste for ornamental gardening. Cabbages grew in plain sight; and a pumpkin vine, rooted at some distance, had run across the intervening space, and deposited one of its gigantic products directly beneath the hall-window; as if to warn the Governor that this great lump of vegetable

THREE ENDINGS The Scarlet Letter has three endings: 1) the scene of the Election Sermon, with Arthur’s sermon and death on the scaffold and the multiple interpretations of the mysterious mark on his breast 2) Hester’s return to Boston after Pearl has gone to Europe as «the richest heiress of her day, in the New World» (thanks to the heirloom Chillingworth bequeaths to her), and her choice to take wear again the scarlet letter 3) the final image of Arthur and Hester’s

ARTHUR’S PROPHECY The romance also ends with two competing prophecies: Arthur’ and Hester’s. Arthur’s sermon, has as its subject «the relation between the Deity and the communities of mankind, with a special reference to the New England which they were here planting in the wilderness. And, as he drew towards the close, a spirit as of prophecy had come upon him, constraining him to its purpose as mightily as the old prophets of Israel were constrained; only with this di�erence, that , whereas the Jewish seers had denounced judgments and ruin on their country, it was his mission to foretell a high and glorious destiny for the newly gathered people of the Lord. » Arthur predicts a glorious future for New England, but the new governor is John Endicott, the embodiment of the worst traits of Puritanism (especially for Hawthorne).

HESTER’S PROPHECY Much less (inadvertently) ironic is Hester’s prophecy, when she comes back to Boston, resumes the letter, and become the center of a sort of «self-awareness group, » where «people brought all their sorrows and perplexities, and besought her counsel, as one who had herself gone through a mighty trouble. Women, more especially, – in the continually recurring trials of wounded, wasted, wronged, misplaced, or erring and sinful passion, – or with the dreary burden of a heart unyielded, because unvalued and unsought, – came to Hester’s cottage, demanding why they were so wretched, and what the remedy! Hester comforted and counselled them, as best she might. She assured them, too, of her firm belief, that, at some brighter period, when the world should have grown ripe for it, in Heaven’s own time, a new truth would be revealed, in order to establish the whole relation between man and woman on a surer ground of mutual happiness. Earlier in life, Hester had vainly imagined that she herself might be the destined prophetess, but had long since recognized the impossibility that any mission of divine and mysterious truth should be confided to a woman

A FEMINIST NON-PROPHETESS Hester foretells a feminist utopia where man and woman will have a relationship based on equality, but refuses to present herself as a prophetess. In this way, she renounces to become a «leader» (what instead Dimmesdale does become, paving the way to a harsher authoritarianism) and listens instead to the people who come to her to speak. These people, especially women, find in Hester’s cottage a space where their voices can be heard and their stories shared. What Hawthorne does with his romance, by giving voice to Hester and her story, Hester does with her fellow citizens, paving the way to what two centuries later will culminate in the 1848

Aubrie scarlet

Aubrie scarlet In what century is the story of hester prynne set

In what century is the story of hester prynne set Description of hester prynne

Description of hester prynne Resisting length of hill road

Resisting length of hill road Lateral force resisting system

Lateral force resisting system Resisting temptation lds

Resisting temptation lds Resisting pressure definition

Resisting pressure definition White men are saving brown women from brown men

White men are saving brown women from brown men Grass letter a

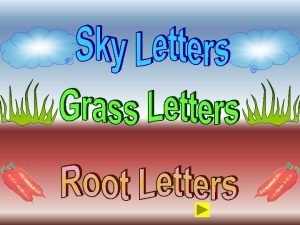

Grass letter a Scarlet letter ch 21

Scarlet letter ch 21 The scarlet letter themes

The scarlet letter themes Chapter 11 summary the scarlet letter

Chapter 11 summary the scarlet letter A throng of bearded men

A throng of bearded men The scarlet letter video

The scarlet letter video Chapter 13 summary scarlet letter

Chapter 13 summary scarlet letter