Keynesian view Discretionary versus nondiscretionary fiscal policy The

![Note: We assume imports are autonomous. Thus the multiplier is given by: [1] We Note: We assume imports are autonomous. Thus the multiplier is given by: [1] We](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/f5b1df55598c9c3a9373143ee224e900/image-11.jpg)

- Slides: 14

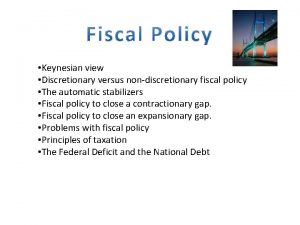

• Keynesian view • Discretionary versus non-discretionary fiscal policy • The automatic stabilizers • Fiscal policy to close a contractionary gap. • The tax multiplier • Fiscal policy to close an expansionary gap. • Problems with fiscal policy

The use of the taxing and spending powers of government to regulate aggregate expenditure, and thereby to stabilize the economy The economy needs to be stabilized. The economy can be stabilized. The economy should be stabilized. This is the Keynesian view

This legislation established a responsibility for the federal government to promote “maximum employment, production, and purchasing power. ”

Discretionary fiscal policy is the deliberate manipulation of government purchases, taxation, and transfer payments to pursue macroeconomic goals such as full employment and price stability. The Bush tax stimulus package of 2008 is an example of discretionary fiscal policy

Non-discretionary or “built-in” features of government spending and taxation that reduce fluctuations in disposable income, and thus consumption, over the business cycle. • Tax rates for various types of income are set by elected officials. Tax collections depend on the employment levels/incomes, profits, capital gains, retails sales, . . . • Elected officials establish eligibility requirements and support levels for needs-tested transfer payments—e. g. , TANF, food stamps, and unemployment compensation. Actual government outlays for needs-tested transfer payments depend on (1) the number of persons eligible; and (2) the number of those eligible that actually file claims.

As the economy enters a recession, federal revenues tend to decline while at the same time transfer payments rise. Thus recession brings about an automatic decline of net taxes (NT) Remember that: DI = Y - NT

If a lack of aggregate expenditure is the problem, why not use the spending and taxing powers of the federal government to stimulate aggregate expenditure

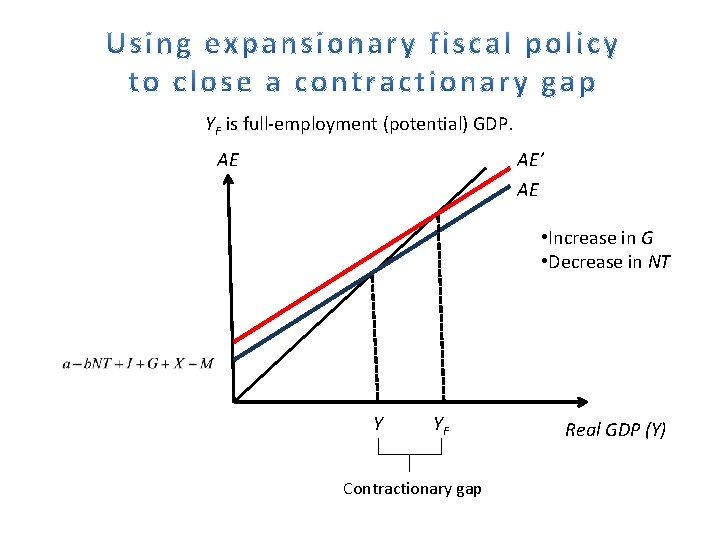

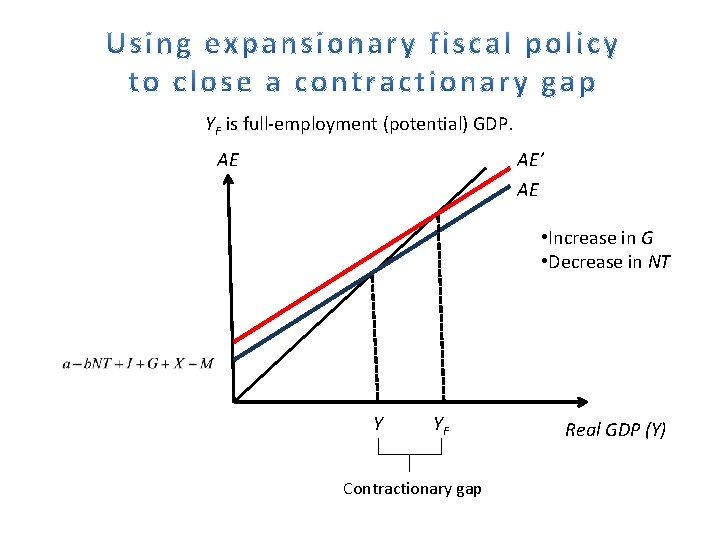

YF is full-employment (potential) GDP. AE AE’ AE • Increase in G • Decrease in NT Y YF Contractionary gap Real GDP (Y)

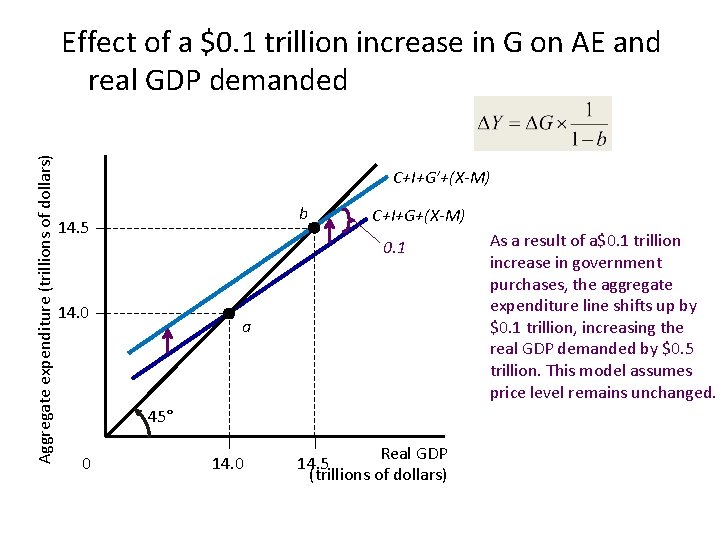

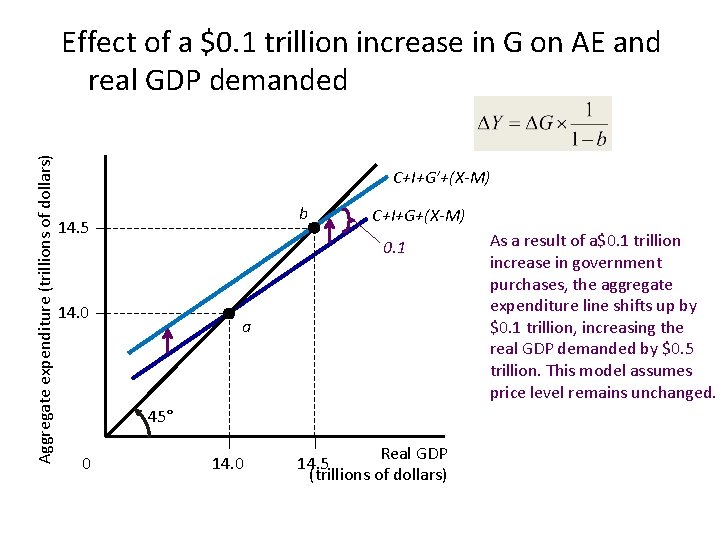

Aggregate expenditure (trillions of dollars) Effect of a $0. 1 trillion increase in G on AE and real GDP demanded C+I+G’+(X-M) b 14. 5 C+I+G+(X-M) 0. 1 14. 0 a 45° 0 14. 0 Real GDP 14. 5 (trillions of dollars) As a result of a$0. 1 trillion increase in government purchases, the aggregate expenditure line shifts up by $0. 1 trillion, increasing the real GDP demanded by $0. 5 trillion. This model assumes price level remains unchanged.

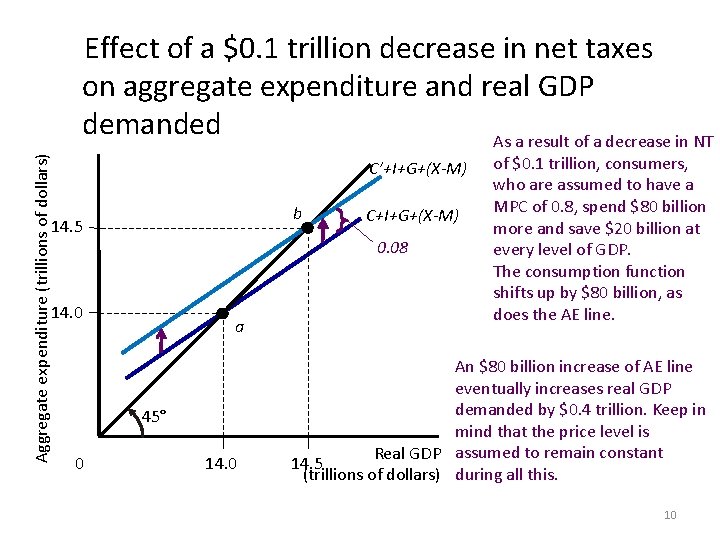

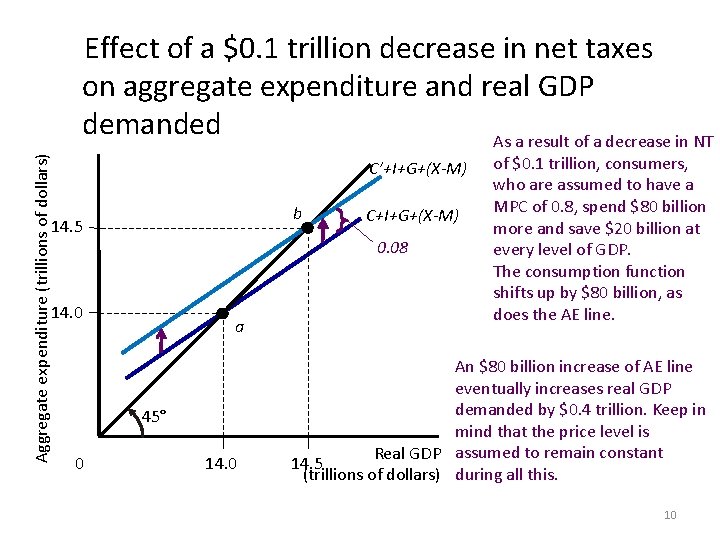

Aggregate expenditure (trillions of dollars) Effect of a $0. 1 trillion decrease in net taxes on aggregate expenditure and real GDP demanded As a result of a decrease in NT C’+I+G+(X-M) b 14. 5 0. 08 14. 0 a 45° 0 C+I+G+(X-M) 14. 0 of $0. 1 trillion, consumers, who are assumed to have a MPC of 0. 8, spend $80 billion more and save $20 billion at every level of GDP. The consumption function shifts up by $80 billion, as does the AE line. An $80 billion increase of AE line eventually increases real GDP demanded by $0. 4 trillion. Keep in mind that the price level is Real GDP assumed to remain constant 14. 5 (trillions of dollars) during all this. 10

![Note We assume imports are autonomous Thus the multiplier is given by 1 We Note: We assume imports are autonomous. Thus the multiplier is given by: [1] We](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/f5b1df55598c9c3a9373143ee224e900/image-11.jpg)

Note: We assume imports are autonomous. Thus the multiplier is given by: [1] We can rewrite [1] as: Tax multiplier

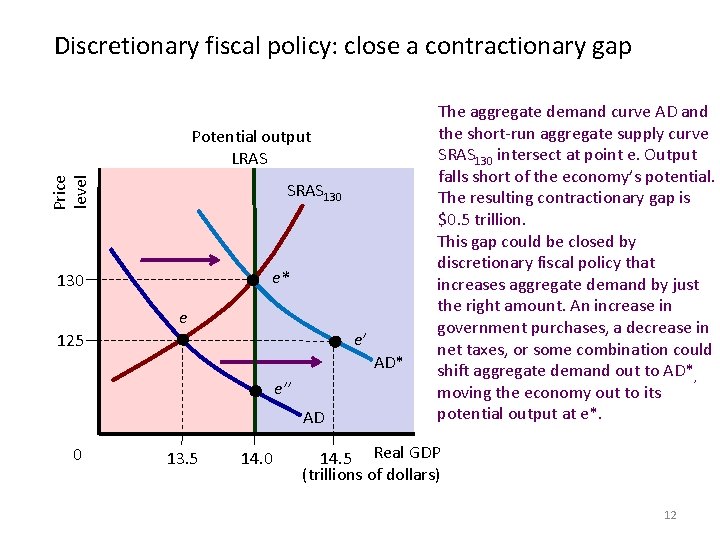

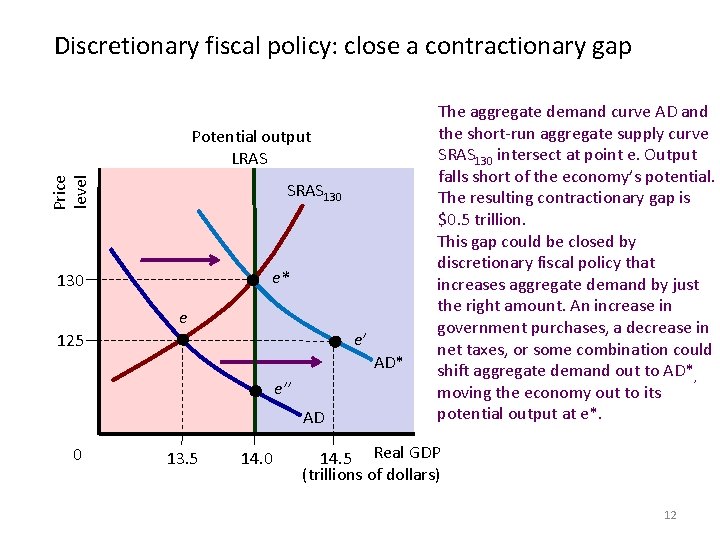

Discretionary fiscal policy: close a contractionary gap Price level Potential output LRAS SRAS 130 e* 130 e e’ 125 AD* e’’ AD 0 13. 5 14. 0 The aggregate demand curve AD and the short-run aggregate supply curve SRAS 130 intersect at point e. Output falls short of the economy’s potential. The resulting contractionary gap is $0. 5 trillion. This gap could be closed by discretionary fiscal policy that increases aggregate demand by just the right amount. An increase in government purchases, a decrease in net taxes, or some combination could shift aggregate demand out to AD*, moving the economy out to its potential output at e*. 14. 5 Real GDP (trillions of dollars) 12

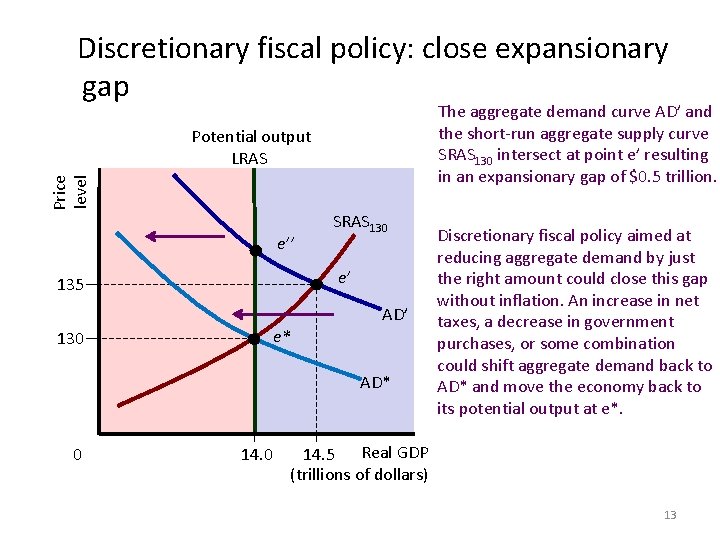

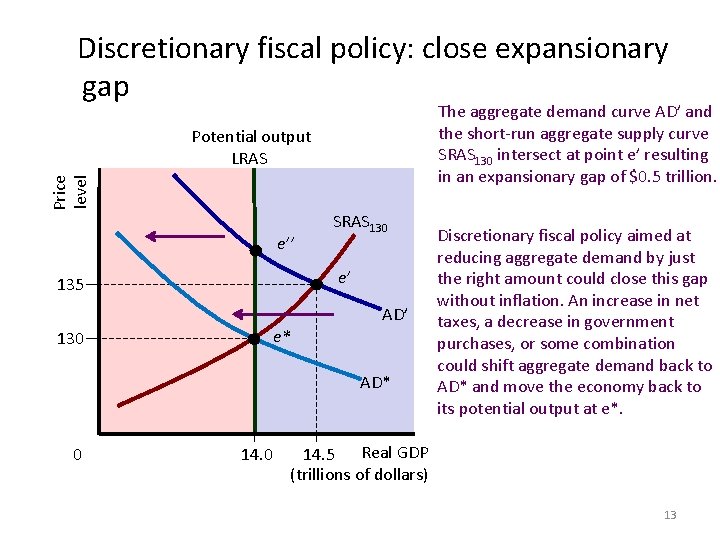

Discretionary fiscal policy: close expansionary gap The aggregate demand curve AD’ and the short-run aggregate supply curve SRAS 130 intersect at point e’ resulting in an expansionary gap of $0. 5 trillion. Price level Potential output LRAS e’’ SRAS 130 e’ 135 AD’ 130 e* AD* 0 14. 0 Discretionary fiscal policy aimed at reducing aggregate demand by just the right amount could close this gap without inflation. An increase in net taxes, a decrease in government purchases, or some combination could shift aggregate demand back to AD* and move the economy back to its potential output at e*. 14. 5 Real GDP (trillions of dollars) 13

1. Policy lags 2. Permanent income

Discretionary vs non discretionary fiscal policy

Discretionary vs non discretionary fiscal policy Neoclassical economics examples

Neoclassical economics examples Classical economics vs keynesian

Classical economics vs keynesian Classical economics vs keynesian

Classical economics vs keynesian Classical economics vs keynesian

Classical economics vs keynesian Fiscal demand side policy

Fiscal demand side policy Fiscal policy practice

Fiscal policy practice Goals of fiscal policy

Goals of fiscal policy Demand side fiscal policy definition

Demand side fiscal policy definition What is liquidity ratio in banking

What is liquidity ratio in banking Fiscal policy definition

Fiscal policy definition Fiscal policy

Fiscal policy Contractionary fiscal policy

Contractionary fiscal policy Components of fiscal policy

Components of fiscal policy Unemployment diagram

Unemployment diagram