How family medicine residents clinical performance relates to

- Slides: 1

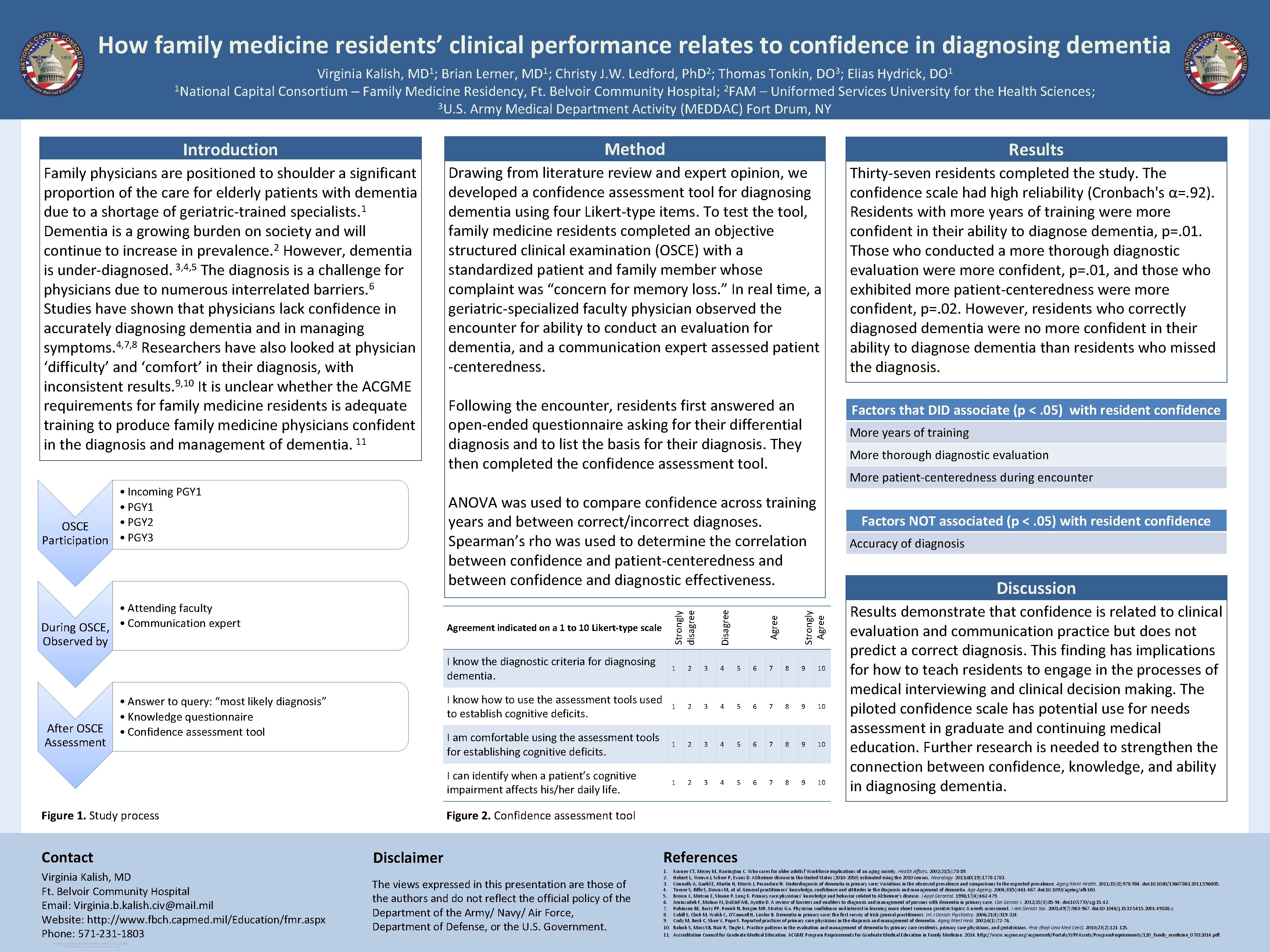

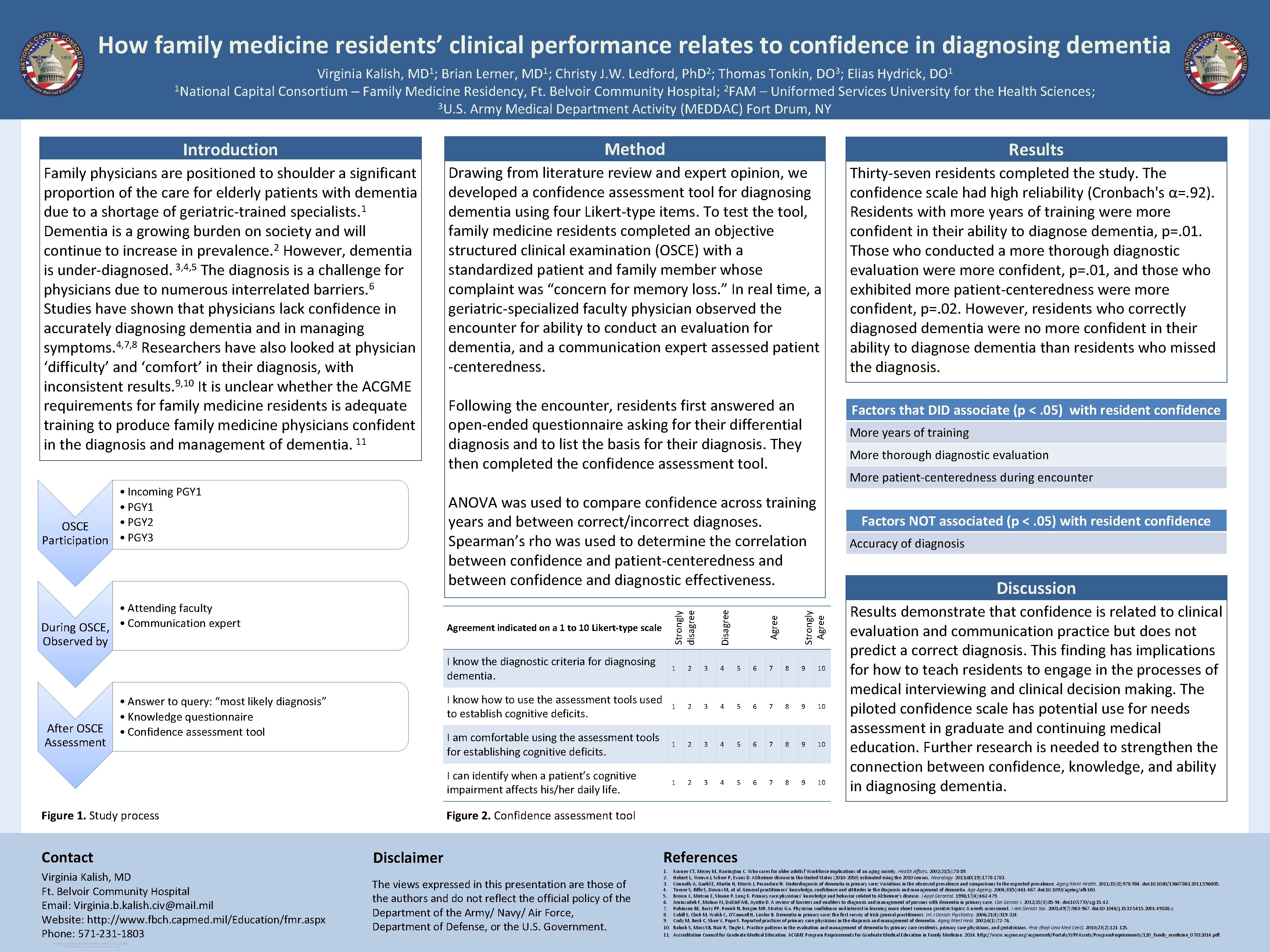

How family medicine residents’ clinical performance relates to confidence in diagnosing dementia Virginia Kalish, MD 1; Brian Lerner, MD 1; Christy J. W. Ledford, Ph. D 2; Thomas Tonkin, DO 3; Elias Hydrick, DO 1 1 National Capital Consortium – Family Medicine Residency, Ft. Belvoir Community Hospital; 2 FAM – Uniformed Services University for the Health Sciences; 3 U. S. Army Medical Department Activity (MEDDAC) Fort Drum, NY Introduction Method Results Family physicians are positioned to shoulder a significant proportion of the care for elderly patients with dementia due to a shortage of geriatric-trained specialists. 1 Dementia is a growing burden on society and will continue to increase in prevalence. 2 However, dementia 3, 4, 5 is under-diagnosed. The diagnosis is a challenge for physicians due to numerous interrelated barriers. 6 Studies have shown that physicians lack confidence in accurately diagnosing dementia and in managing symptoms. 4, 7, 8 Researchers have also looked at physician ‘difficulty’ and ‘comfort’ in their diagnosis, with inconsistent results. 9, 10 It is unclear whether the ACGME requirements for family medicine residents is adequate training to produce family medicine physicians confident in the diagnosis and management of dementia. 11 Drawing from literature review and expert opinion, we developed a confidence assessment tool for diagnosing dementia using four Likert-type items. To test the tool, family medicine residents completed an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) with a standardized patient and family member whose complaint was “concern for memory loss. ” In real time, a geriatric-specialized faculty physician observed the encounter for ability to conduct an evaluation for dementia, and a communication expert assessed patient -centeredness. Thirty-seven residents completed the study. The confidence scale had high reliability (Cronbach's α=. 92). Residents with more years of training were more confident in their ability to diagnose dementia, p=. 01. Those who conducted a more thorough diagnostic evaluation were more confident, p=. 01, and those who exhibited more patient-centeredness were more confident, p=. 02. However, residents who correctly diagnosed dementia were no more confident in their ability to diagnose dementia than residents who missed the diagnosis. Following the encounter, residents first answered an open-ended questionnaire asking for their differential diagnosis and to list the basis for their diagnosis. They then completed the confidence assessment tool. Factors that DID associate (p <. 05) with resident confidence • Incoming PGY 1 • PGY 2 OSCE Participation • PGY 3 Figure 1. Study process Virginia Kalish, MD Ft. Belvoir Community Hospital Email: Virginia. b. kalish. civ@mail. mil Website: http: //www. fbch. capmed. mil/Education/fmr. aspx Phone: 571 -231 -1803 More patient-centeredness during encounter Disagree Factors NOT associated (p <. 05) with resident confidence Accuracy of diagnosis Discussion I know the diagnostic criteria for diagnosing dementia. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 I know how to use the assessment tools used to establish cognitive deficits. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 I am comfortable using the assessment tools for establishing cognitive deficits. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 I can identify when a patient’s cognitive impairment affects his/her daily life. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Agree Strongly Agreement indicated on a 1 to 10 Likert-type scale Strongly disagree • Answer to query: “most likely diagnosis” • Knowledge questionnaire • Confidence assessment tool Contact More thorough diagnostic evaluation ANOVA was used to compare confidence across training years and between correct/incorrect diagnoses. Spearman’s rho was used to determine the correlation between confidence and patient-centeredness and between confidence and diagnostic effectiveness. • Attending faculty During OSCE, • Communication expert Observed by After OSCE Assessment More years of training Results demonstrate that confidence is related to clinical evaluation and communication practice but does not predict a correct diagnosis. This finding has implications for how to teach residents to engage in the processes of medical interviewing and clinical decision making. The piloted confidence scale has potential use for needs assessment in graduate and continuing medical education. Further research is needed to strengthen the connection between confidence, knowledge, and ability in diagnosing dementia. Figure 2. Confidence assessment tool Disclaimer References The views expressed in this presentation are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Department of the Army/ Navy/ Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U. S. Government. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. Kovner CT, Mezey M, Harrington C. Who cares for older adults? Workforce implications of an aging society. Health Affairs. 2002; 21(5): 78 -89. Hebert L, Weuve J, Scherr P, Evans D. Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010 -2050) estimated using the 2010 census. Neurology. 2013; 80(19): 1778 -1783. Connolly A, Gaehl E, Martin H, Morris J, Purandare N. Underdiagnosis of dementia in primary care: Variations in the observed prevalence and comparisons to the expected prevalence. Aging Ment Health. 2011; 15(8): 978 -984. doi: 10. 1080/13607863. 2011. 596805. Turner S, Iliffe S, Downs M, et al. General practitioners’ knowledge, confidence and attitudes in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Ageing. 2004; 33(5): 461 -467. doi: 10. 1093/ageing/afh 140. Brown C, Mutran E, Sloane P, Long K. Primary care physicians’ knowledge and behavior related to Alzheimer's disease. J Appl Gerontol. 1998; 17(4): 462 -479. Aminzadeh F, Molnar FJ, Dalziel WB, Ayotte D. A review of barriers and enablers to diagnosis and management of persons with dementia in primary care. Can Geriatr J. 2012; 15(3): 85 -94. doi: 10. 5770/cgj. 15. 42. Robinson BE, Barry PP, Renick N, Bergen MR, Stratos G a. Physician confidence and interest in learning more about common geriatric topics: A needs assessment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001; 49(7): 963 -967. doi: 10. 1046/j. 1532 -5415. 2001. 49188. x. Cahill S, Clark M, Walsh C, O’Connell H, Lawlor B. Dementia in primary care: the first survey of Irish general practitioners. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006; 21(4): 319 -324. Cody M, Beck C, Shue V, Pope S. Reported practices of primary care physicians in the diagnosis and management of dementia. Aging Ment Heal. 2002; 6(1): 72 -76. Baloch S, Moss SB, Nair R, Tingle L. Practice patterns in the evaluation and management of dementia by primary care residents, primary care physicians, and geriatricians. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2010; 23(2): 121 -125. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. 2014. http: //www. acgme. org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/Program. Requirements/120_family_medicine_07012014. pdf.