Families communities and social change then and now

- Slides: 13

Families, communities and social change: then and now Nickie Charles Centre for the Study of Women and Gender University of Warwick NCRM Community Re-studies April 12 2011, Nottingham

Outline • The re-study and the baseline study that preceded it • Theoretical assumptions • Analytical categories such as gender, ‘race’/ethnicity, class

The baseline study • Carried out in Swansea in 1960 by Colin Rosser and Chris Harris • Urban community study • Extended family • Focussed on patterns of residence and frequency of contact between different categories of kin • 2, 000 -household survey supplemented by ethnographic research

Findings • Women at centre of kinship networks • Grouping wider than elementary family of parents and children, 3 -generational, somewhere between co-resident group and social network • Modified extended family – fitting a mobile society which was geographically, occupationally and culturally differentiated

Social change in 20 th century • Shift from cohesive to mobile society • Social solidarity of 3 -generational kin group weakened • Increasing differentiation of the occupational structure, increasing cultural differentiation, changes in the means of communication, specifically phones and cars

The re-study • Original data ‘lost’ therefore no re-analysis of it possible • Chris Harris one of the research team • Replication of original study • 1, 000 -household survey supplemented by ethnographic research in four localities • Interviewed 122 women, 71 men, aged between 19 and 92 years, 18 of whom from ethnic minority

What were their questions? • Structural functionalism dominant paradigm in 1950 s and early 1960 s • Central question: What are the effects ‘of social and cultural change on the structure of the extended family? ’ (R&H, 1965: 18) • Focus on system and structure • Asking this question found two forms of extended family – cohesive and mobile society

Mr Griffith Hughes • Loss of family solidarity, emergence of individualistic and self-centred attitudes • ‘He is talking of two radically different worlds, and describing in effect two distinct patterns of family behaviour. The first is that of his earlier years and is based fundamentally on the close clustering of kin in a limited locality, with a high degree of social and economic homogeneity and with close and complex ties of mutual co-operation between kin and neighbours. The second is that of his present family, a modified version of the former, continuing much of the older patterns but altogether looser in structure with a much wider scatter of relatives, and markedly heterogeneous in occupation and income and in social and cultural values’ (Rosser and Harris, 1965: 15).

Conceptualising social change • Focus on structure – the way ‘the’ family is structured and how this structure changes in response to changes in the wider social system • Structural change (hence social change) is brought about by increasing differentiation – occupational, geographical, cultural – leading to a decline in social solidarity • Shift from cohesive to mobile society

Structure and practice (agency? ) • Restudy explored effects of increasing differentiation on family solidarity • Increased occupational and geographical differentiation – now within ‘elementary’ as well as ‘extended’ family • Despite this, extended family networks provide support (and include friends, animals) • Suggests Durkheim’s assumptions not borne out in practice • Survey analysis contrasts with analysis of ethnographic data – ‘family practices’ and fluidity

Cultural identities • Definition of class included generational and cultural dimension as well as occupation • Ethnicity addressed through Welshness – also included generational dimension though no self-assessment • Cultural identity important because of theoretical significance of increasing cultural differentiation

Why were we constrained? • Need for comparison • Loss of original data • Assumptions about ‘the family’ and its relation to society embedded in questionnaire • One of original researchers carried out analysis of survey data • Sociological habitus

Conclusions • Methodology allowed us to see continuity as well as change • Permitted historical depth • Connections and solidarity maintained despite increasing differentiation – implied critique of Durkheim • Ethnographic data analysed differently, in terms of family practices

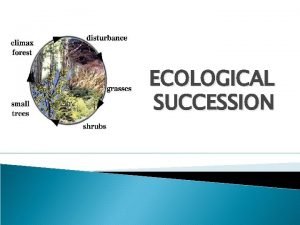

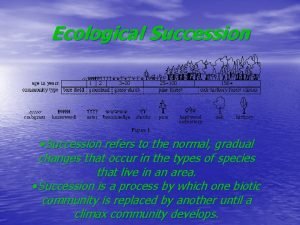

Steps in primary succession

Steps in primary succession Big families vs small families

Big families vs small families Communities change over time

Communities change over time The gradual change in living communities

The gradual change in living communities When does a climax community change?

When does a climax community change? Sociology: then and now

Sociology: then and now Sociology: then and now practice

Sociology: then and now practice Seaside holidays then and now

Seaside holidays then and now Seaside holidays then and now

Seaside holidays then and now John purdy folding chair

John purdy folding chair Dubai before and after oil

Dubai before and after oil Agriculture now and then

Agriculture now and then Child labor then vs now venn diagram

Child labor then vs now venn diagram Seaside holidays then and now

Seaside holidays then and now