Examining Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors Impacting Mens Decisions

- Slides: 1

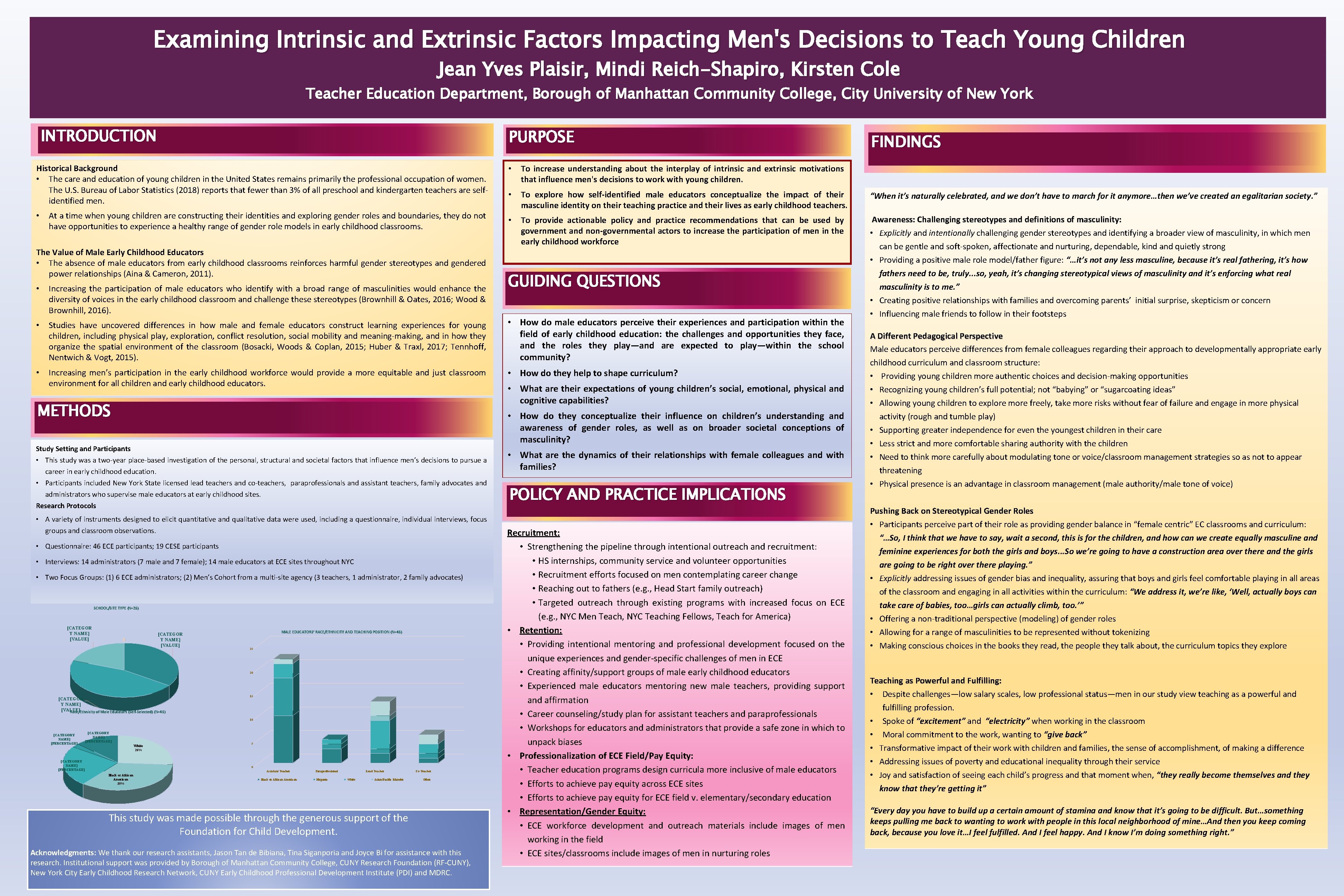

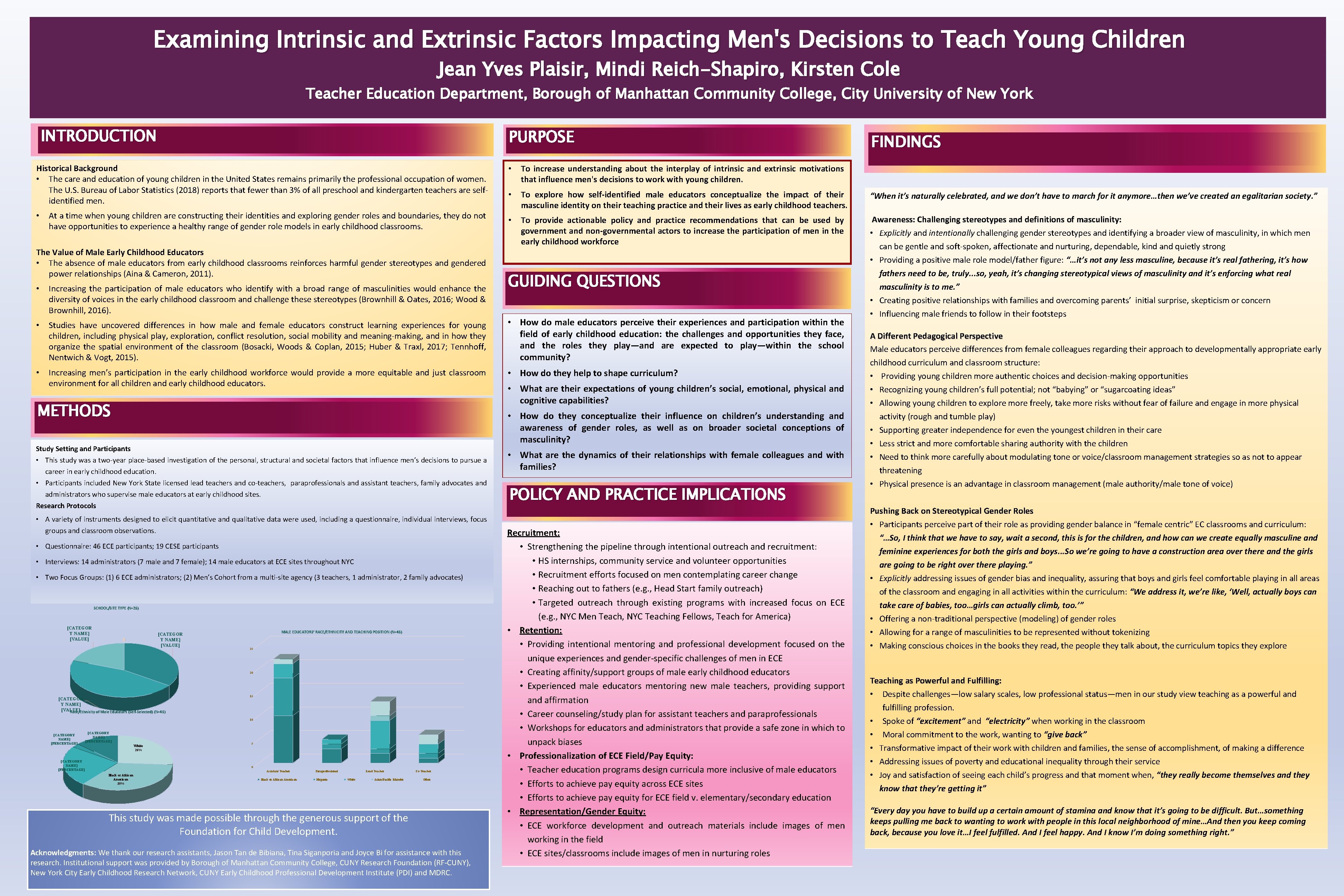

Examining Intrinsic and Extrinsic Factors Impacting Men's Decisions to Teach Young Children Jean Yves Plaisir, Mindi Reich-Shapiro, Kirsten Cole Teacher Education Department, Borough of Manhattan Community College, City University of New York INTRODUCTION PURPOSE Historical Background • The care and education of young children in the United States remains primarily the professional occupation of women. The U. S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2018) reports that fewer than 3% of all preschool and kindergarten teachers are selfidentified men. • At a time when young children are constructing their identities and exploring gender roles and boundaries, they do not have opportunities to experience a healthy range of gender role models in early childhood classrooms. The Value of Male Early Childhood Educators • The absence of male educators from early childhood classrooms reinforces harmful gender stereotypes and gendered power relationships (Aina & Cameron, 2011). • To increase understanding about the interplay of intrinsic and extrinsic motivations that influence men's decisions to work with young children. • To explore how self-identified male educators conceptualize the impact of their masculine identity on their teaching practice and their lives as early childhood teachers. “When it’s naturally celebrated, and we don’t have to march for it anymore…then we’ve created an egalitarian society. ” • To provide actionable policy and practice recommendations that can be used by government and non-governmental actors to increase the participation of men in the early childhood workforce Awareness: Challenging stereotypes and definitions of masculinity: • Explicitly and intentionally challenging gender stereotypes and identifying a broader view of masculinity, in which men can be gentle and soft-spoken, affectionate and nurturing, dependable, kind and quietly strong • Providing a positive male role model/father figure: “…it’s not any less masculine, because it’s real fathering, it’s how fathers need to be, truly. . . so, yeah, it’s changing stereotypical views of masculinity and it’s enforcing what real masculinity is to me. ” • Creating positive relationships with families and overcoming parents’ initial surprise, skepticism or concern • Influencing male friends to follow in their footsteps GUIDING QUESTIONS • Increasing the participation of male educators who identify with a broad range of masculinities would enhance the diversity of voices in the early childhood classroom and challenge these stereotypes (Brownhill & Oates, 2016; Wood & Brownhill, 2016). • Studies have uncovered differences in how male and female educators construct learning experiences for young children, including physical play, exploration, conflict resolution, social mobility and meaning-making, and in how they organize the spatial environment of the classroom (Bosacki, Woods & Coplan, 2015; Huber & Traxl, 2017; Tennhoff, Nentwich & Vogt, 2015). • How do male educators perceive their experiences and participation within the field of early childhood education: the challenges and opportunities they face, and the roles they play—and are expected to play—within the school community? Increasing men’s participation in the early childhood workforce would provide a more equitable and just classroom environment for all children and early childhood educators. • How do they help to shape curriculum? • METHODS Study Setting and Participants • This study was a two-year place-based investigation of the personal, structural and societal factors that influence men’s decisions to pursue a career in early childhood education. • Participants included New York State licensed lead teachers and co-teachers, paraprofessionals and assistant teachers, family advocates and administrators who supervise male educators at early childhood sites. Research Protocols • A variety of instruments designed to elicit quantitative and qualitative data were used, including a questionnaire, individual interviews, focus groups and classroom observations. • Questionnaire: 46 ECE participants; 19 CESE participants • Interviews: 14 administrators (7 male and 7 female); 14 male educators at ECE sites throughout NYC • Two Focus Groups: (1) 6 ECE administrators; (2) Men’s Cohort from a multi-site agency (3 teachers, 1 administrator, 2 family advocates) SCHOOL/SITE TYPE (N=26) [CATEGOR Y NAME] [VALUE] 0 MALE EDUCATORS’ RACE/ETHNICITY AND TEACHING POSITION (N=46) 25 20 [CATEGOR Y NAME] [VALUE] Race/Ethnicity of Male Educators (Self-Selected) (N=46) 15 10 [CATEGORY NAME] [PERCENTAGE] White 26% [CATEGORY NAME] [PERCENTAGE] 5 0 Assistant Teacher Black or African American 35% Black or African American Paraprofessional Hispanic Lead Teacher White Asian/Pacific Islander Co-Teacher Other This study was made possible through the generous support of the Foundation for Child Development. Acknowledgments: We thank our research assistants, Jason Tan de Bibiana, Tina Siganporia and Joyce Bi for assistance with this research. Institutional support was provided by Borough of Manhattan Community College, CUNY Research Foundation (RF-CUNY), New York City Early Childhood Research Network, CUNY Early Childhood Professional Development Institute (PDI) and MDRC. FINDINGS • What are their expectations of young children’s social, emotional, physical and cognitive capabilities? • How do they conceptualize their influence on children’s understanding and awareness of gender roles, as well as on broader societal conceptions of masculinity? • What are the dynamics of their relationships with female colleagues and with families? POLICY AND PRACTICE IMPLICATIONS Recruitment: • Strengthening the pipeline through intentional outreach and recruitment: • HS internships, community service and volunteer opportunities • Recruitment efforts focused on men contemplating career change • Reaching out to fathers (e. g. , Head Start family outreach) • Targeted outreach through existing programs with increased focus on ECE (e. g. , NYC Men Teach, NYC Teaching Fellows, Teach for America) • Retention: • Providing intentional mentoring and professional development focused on the unique experiences and gender-specific challenges of men in ECE • Creating affinity/support groups of male early childhood educators • Experienced male educators mentoring new male teachers, providing support and affirmation • Career counseling/study plan for assistant teachers and paraprofessionals • Workshops for educators and administrators that provide a safe zone in which to unpack biases • Professionalization of ECE Field/Pay Equity: • Teacher education programs design curricula more inclusive of male educators • Efforts to achieve pay equity across ECE sites • Efforts to achieve pay equity for ECE field v. elementary/secondary education • Representation/Gender Equity: • ECE workforce development and outreach materials include images of men working in the field • ECE sites/classrooms include images of men in nurturing roles A Different Pedagogical Perspective Male educators perceive differences from female colleagues regarding their approach to developmentally appropriate early childhood curriculum and classroom structure: • Providing young children more authentic choices and decision-making opportunities • Recognizing young children’s full potential; not “babying” or “sugarcoating ideas” • Allowing young children to explore more freely, take more risks without fear of failure and engage in more physical activity (rough and tumble play) • Supporting greater independence for even the youngest children in their care • Less strict and more comfortable sharing authority with the children • Need to think more carefully about modulating tone or voice/classroom management strategies so as not to appear threatening • Physical presence is an advantage in classroom management (male authority/male tone of voice) Pushing Back on Stereotypical Gender Roles • Participants perceive part of their role as providing gender balance in “female centric” EC classrooms and curriculum: “…So, I think that we have to say, wait a second, this is for the children, and how can we create equally masculine and • • feminine experiences for both the girls and boys. . . So we’re going to have a construction area over there and the girls are going to be right over there playing. ” Explicitly addressing issues of gender bias and inequality, assuring that boys and girls feel comfortable playing in all areas of the classroom and engaging in all activities within the curriculum: “We address it, we’re like, ‘Well, actually boys can take care of babies, too…girls can actually climb, too. ’” Offering a non-traditional perspective (modeling) of gender roles Allowing for a range of masculinities to be represented without tokenizing Making conscious choices in the books they read, the people they talk about, the curriculum topics they explore Teaching as Powerful and Fulfilling: • Despite challenges—low salary scales, low professional status—men in our study view teaching as a powerful and fulfilling profession. • Spoke of “excitement” and “electricity” when working in the classroom • Moral commitment to the work, wanting to “give back” • Transformative impact of their work with children and families, the sense of accomplishment, of making a difference • Addressing issues of poverty and educational inequality through their service • Joy and satisfaction of seeing each child’s progress and that moment when, “they really become themselves and they know that they’re getting it” “Every day you have to build up a certain amount of stamina and know that it’s going to be difficult. But…something keeps pulling me back to wanting to work with people in this local neighborhood of mine…And then you keep coming back, because you love it…I feel fulfilled. And I feel happy. And I know I’m doing something right. ”