Error estimations of dry deposition velocities of air

- Slides: 1

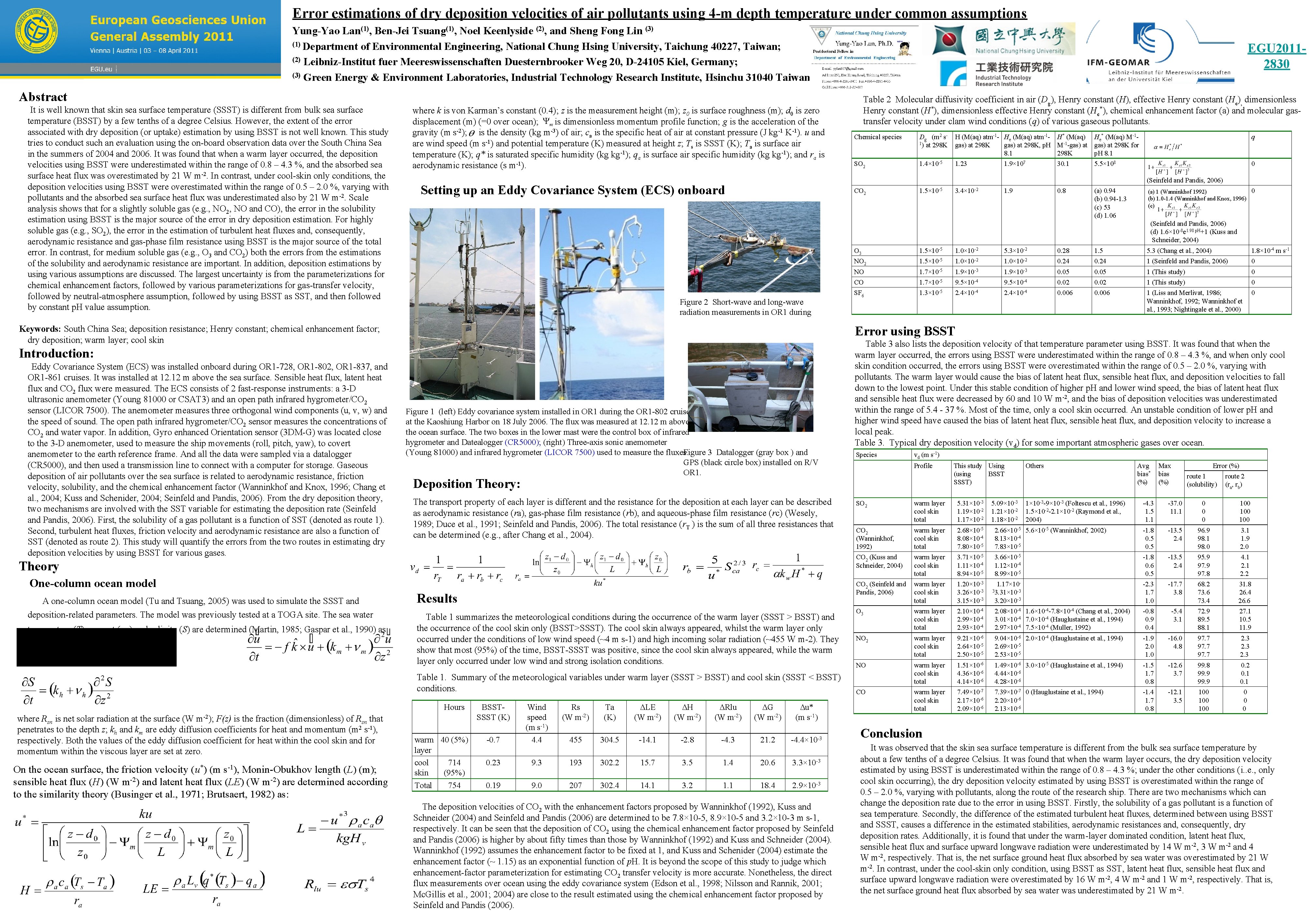

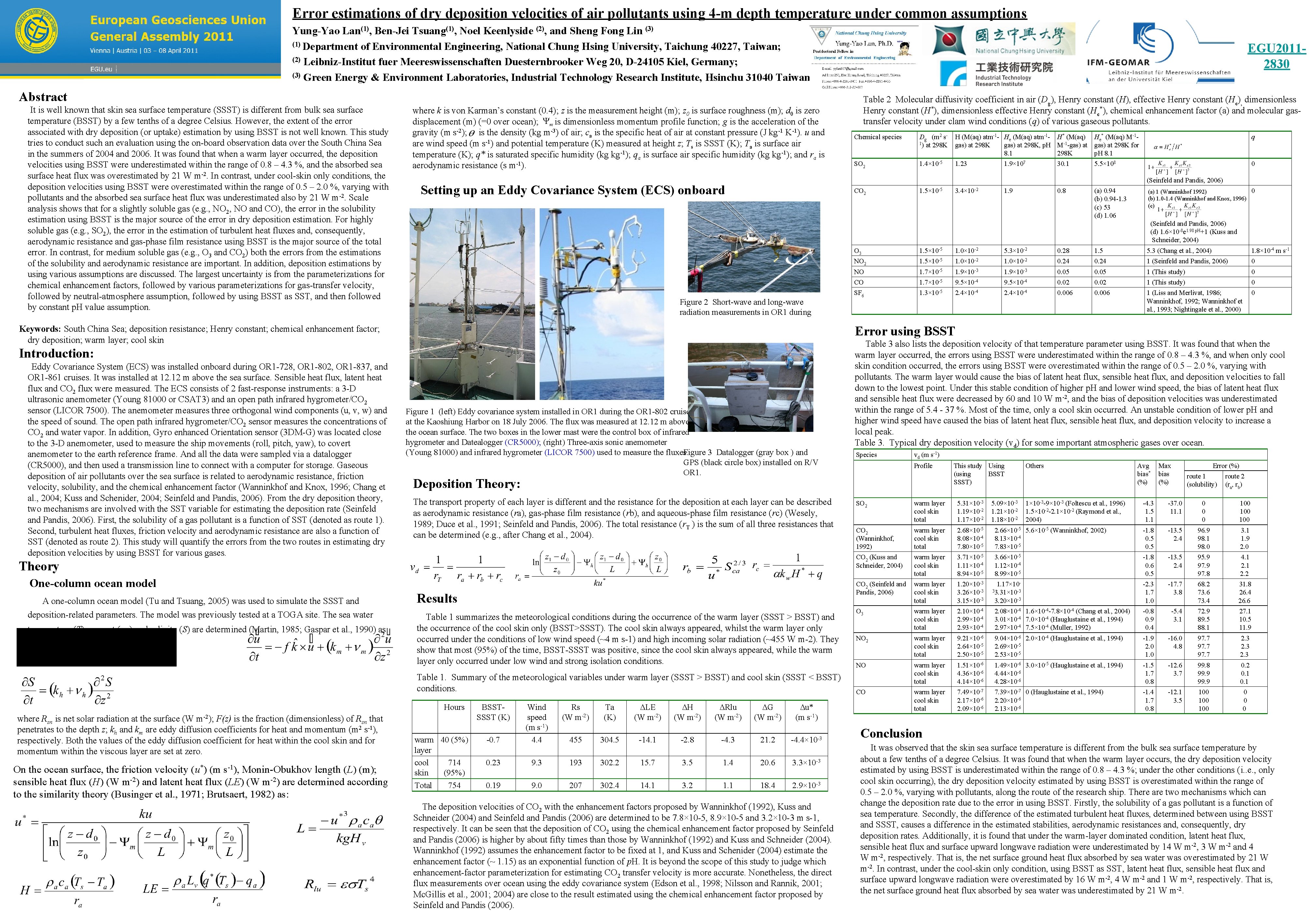

Error estimations of dry deposition velocities of air pollutants using 4 -m depth temperature under common assumptions Yung-Yao Lan(1), Ben-Jei Tsuang(1), Noel Keenlyside (2), and Sheng Fong Lin (3) (1) Department of Environmental Engineering, National Chung Hsing University, Taichung 40227, Taiwan; (2) Leibniz-Institut fuer Meereswissenschaften Duesternbrooker Weg 20, D-24105 Kiel, Germany; (3) Green Energy & Environment Laboratories, Industrial Technology Research Institute, Hsinchu 31040 Taiwan EGU 20112830 Abstract It is well known that skin sea surface temperature (SSST) is different from bulk sea surface temperature (BSST) by a few tenths of a degree Celsius. However, the extent of the error associated with dry deposition (or uptake) estimation by using BSST is not well known. This study tries to conduct such an evaluation using the on-board observation data over the South China Sea in the summers of 2004 and 2006. It was found that when a warm layer occurred, the deposition velocities using BSST were underestimated within the range of 0. 8 – 4. 3 %, and the absorbed sea surface heat flux was overestimated by 21 W m-2. In contrast, under cool-skin only conditions, the deposition velocities using BSST were overestimated within the range of 0. 5 – 2. 0 %, varying with pollutants and the absorbed sea surface heat flux was underestimated also by 21 W m-2. Scale analysis shows that for a slightly soluble gas (e. g. , NO 2, NO and CO), the error in the solubility estimation using BSST is the major source of the error in dry deposition estimation. For highly soluble gas (e. g. , SO 2), the error in the estimation of turbulent heat fluxes and, consequently, aerodynamic resistance and gas-phase film resistance using BSST is the major source of the total error. In contrast, for medium soluble gas (e. g. , O 3 and CO 2) both the errors from the estimations of the solubility and aerodynamic resistance are important. In addition, deposition estimations by using various assumptions are discussed. The largest uncertainty is from the parameterizations for chemical enhancement factors, followed by various parameterizations for gas-transfer velocity, followed by neutral-atmosphere assumption, followed by using BSST as SST, and then followed by constant p. H value assumption. where k is von Karman’s constant (0. 4); z is the measurement height (m); z 0 is surface roughness (m); d 0 is zero displacement (m) (=0 over ocean); is dimensionless momentum profile function; g is the acceleration of the gravity (m s-2); is the density (kg m-3) of air; ca is the specific heat of air at constant pressure (J kg-1 K-1). u and are wind speed (m s-1) and potential temperature (K) measured at height z; Ts is SSST (K); Ta is surface air temperature (K); q* is saturated specific humidity (kg kg-1); qa is surface air specific humidity (kg kg-1); and ra is aerodynamic resistance (s m-1). Setting up an Eddy Covariance System (ECS) onboard Figure 2 Short-wave and long-wave radiation measurements in OR 1 during Figure 1 (left) Eddy covariance system installed in OR 1 during the OR 1 -802 cruise at the Kaoshiung Harbor on 18 July 2006. The flux was measured at 12. 12 m above the ocean surface. The two boxes in the lower mast were the control box of infrared hygrometer and Datealogger (CR 5000); (right) Three-axis sonic anemometer (Young 81000) and infrared hygrometer (LICOR 7500) used to measure the fluxes. Figure 3 Datalogger (gray box ) and GPS (black circle box) installed on R/V OR 1. The transport property of each layer is different and the resistance for the deposition at each layer can be described as aerodynamic resistance (ra), gas-phase film resistance (rb), and aqueous-phase film resistance (rc) (Wesely, 1989; Duce et al. , 1991; Seinfeld and Pandis, 2006). The total resistance (r. T ) is the sum of all three resistances that can be determined (e. g. , after Chang et al. , 2004). Results Table 1 summarizes the meteorological conditions during the occurrence of the warm layer (SSST > BSST) and the occurrence of the cool skin only (BSST>SSST). The cool skin always appeared, whilst the warm layer only occurred under the conditions of low wind speed (~4 m s-1) and high incoming solar radiation (~455 W m-2). They show that most (95%) of the time, BSST-SSST was positive, since the cool skin always appeared, while the warm layer only occurred under low wind and strong isolation conditions. Hours On the ocean surface, the friction velocity (u*) (m s-1), Monin-Obukhov length (L) (m); sensible heat flux (H) (W m-2) and latent heat flux (LE) (W m-2) are determined according to the similarity theory (Businger et al. , 1971; Brutsaert, 1982) as: q SO 2 1. 4× 10 -5 1. 23 5. 5× 108 0 1. 5× 10 -5 1. 9× 107 30. 1 3. 4× 10 -2 1. 9 0. 8 (a) 0. 94 (b) 0. 94 -1. 3 (c) 53 (d) 1. 06 0 (a) 1 (Wanninkhof 1992) (b) 1. 0 -1. 4 (Wanninkhof and Knox, 1996) (c) O 3 1. 5× 10 -5 1. 0× 10 -2 5. 3× 10 -2 0. 28 1. 5 5. 3 (Chang et al. , 2004) 1. 8× 10 -4 m s-1 NO 2 1. 5× 10 -5 1. 0× 10 -2 0. 24 1 (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2006) 0 NO 1. 7× 10 -5 1. 9× 10 -3 0. 05 1 (This study) 0 CO 1. 7× 10 -5 9. 5× 10 -4 0. 02 1 (This study) 0 SF 6 1. 3× 10 -5 2. 4× 10 -4 0. 006 1 (Liss and Merlivat, 1986; Wanninkhof, 1992; Wanninkhof et al. , 1993; Nightingale et al. , 2000) 0 Table 3 also lists the deposition velocity of that temperature parameter using BSST. It was found that when the warm layer occurred, the errors using BSST were underestimated within the range of 0. 8 – 4. 3 %, and when only cool skin condition occurred, the errors using BSST were overestimated within the range of 0. 5 – 2. 0 %, varying with pollutants. The warm layer would cause the bias of latent heat flux, sensible heat flux, and deposition velocities to fall down to the lowest point. Under this stable condition of higher p. H and lower wind speed, the bias of latent heat flux and sensible heat flux were decreased by 60 and 10 W m-2, and the bias of deposition velocities was underestimated within the range of 5. 4 - 37 %. Most of the time, only a cool skin occurred. An unstable condition of lower p. H and higher wind speed have caused the bias of latent heat flux, sensible heat flux, and deposition velocity to increase a local peak. Table 3. Typical dry deposition velocity (vd) for some important atmospheric gases over ocean. Species vd (m s-1) Profile Deposition Theory: Table 1. Summary of the meteorological variables under warm layer (SSST > BSST) and cool skin (SSST < BSST) conditions. where Rsn is net solar radiation at the surface (W m-2); F(z) is the fraction (dimensionless) of Rsn that penetrates to the depth z; kh and km are eddy diffusion coefficients for heat and momentum (m 2 s-1), respectively. Both the values of the eddy diffusion coefficient for heat within the cool skin and for momentum within the viscous layer are set at zero. He* (M(aq) M-1 gas) at 298 K for p. H 8. 1 Error using BSST One-column ocean model temperature (T), current ( u ) and salinity (S) are determined (Martin, 1985; Gaspar et al. , 1990) as: H (M(aq) atm-1 - He (M(aq) atm-1 - H* (M(aq) gas) at 298 K, p. H M-1 -gas) at 8. 1 298 K (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2006) (d) 1. 6× 10 -8 e 1. 98 p. H+1 (Kuss and Schneider, 2004) Theory deposition-related parameters. The model was previously tested at a TOGA site. The sea water Dg (m 2 s 1) at 298 K CO 2 Introduction: A one-column ocean model (Tu and Tsuang, 2005) was used to simulate the SSST and Chemical species (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2006) Keywords: South China Sea; deposition resistance; Henry constant; chemical enhancement factor; dry deposition; warm layer; cool skin Eddy Covariance System (ECS) was installed onboard during OR 1 -728, OR 1 -802, OR 1 -837, and OR 1 -861 cruises. It was installed at 12. 12 m above the sea surface. Sensible heat flux, latent heat flux and CO 2 flux were measured. The ECS consists of 2 fast-response instruments: a 3 -D ultrasonic anemometer (Young 81000 or CSAT 3) and an open path infrared hygrometer/CO 2 sensor (LICOR 7500). The anemometer measures three orthogonal wind components (u, v, w) and the speed of sound. The open path infrared hygrometer/CO 2 sensor measures the concentrations of CO 2 and water vapor. In addition, Gyro enhanced Orientation sensor (3 DM-G) was located close to the 3 -D anemometer, used to measure the ship movements (roll, pitch, yaw), to covert anemometer to the earth reference frame. And all the data were sampled via a datalogger (CR 5000), and then used a transmission line to connect with a computer for storage. Gaseous deposition of air pollutants over the sea surface is related to aerodynamic resistance, friction velocity, solubility, and the chemical enhancement factor (Wanninkhof and Knox, 1996; Chang et al. , 2004; Kuss and Schenider, 2004; Seinfeld and Pandis, 2006). From the dry deposition theory, two mechanisms are involved with the SST variable for estimating the deposition rate (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2006). First, the solubility of a gas pollutant is a function of SST (denoted as route 1). Second, turbulent heat fluxes, friction velocity and aerodynamic resistance are also a function of SST (denoted as route 2). This study will quantify the errors from the two routes in estimating dry deposition velocities by using BSST for various gases. Table 2 Molecular diffusivity coefficient in air (Dg), Henry constant (H), effective Henry constant (He), dimensionless Henry constant (H*), dimensionless effective Henry constant (He*), chemical enhancement factor (a) and molecular gastransfer velocity under clam wind conditions (q) of various gaseous pollutants. warm 40 (5%) layer cool 714 skin (95%) Total 754 BSSTSSST (K) Rs (W m-2) -0. 7 Wind speed (m s-1) 4. 4 Ta (K) ΔLE (W m-2) ΔH (W m-2) 455 304. 5 -14. 1 -2. 8 0. 23 9. 3 193 302. 2 15. 7 0. 19 9. 0 207 302. 4 14. 1 ΔRlu (W m-2) ΔG (W m-2) Δu* (m s-1) -4. 3 21. 2 -4. 4× 10 -3 3. 5 1. 4 20. 6 3. 3× 10 -3 3. 2 1. 1 18. 4 2. 9× 10 -3 The deposition velocities of CO 2 with the enhancement factors proposed by Wanninkhof (1992), Kuss and Schneider (2004) and Seinfeld and Pandis (2006) are determined to be 7. 8× 10 -5, 8. 9× 10 -5 and 3. 2× 10 -3 m s-1, respectively. It can be seen that the deposition of CO 2 using the chemical enhancement factor proposed by Seinfeld and Pandis (2006) is higher by about fifty times than those by Wanninkhof (1992) and Kuss and Schneider (2004). Wanninkhof (1992) assumes the enhancement factor to be fixed at 1, and Kuss and Schenider (2004) estimate the enhancement factor (~ 1. 15) as an exponential function of p. H. It is beyond the scope of this study to judge which enhancement-factor parameterization for estimating CO 2 transfer velocity is more accurate. Nonetheless, the direct flux measurements over ocean using the eddy covariance system (Edson et al. , 1998; Nilsson and Rannik, 2001; Mc. Gillis et al. , 2001; 2004) are close to the result estimated using the chemical enhancement factor proposed by Seinfeld and Pandis (2006). This study Using (using BSST SSST) SO 2 warm layer cool skin total 5. 31× 10 -3 1. 19× 10 -2 1. 17× 10 -2 CO 2 (Wanninkhof, 1992) warm layer cool skin total 2. 68× 10 -5 8. 08× 10 -4 7. 80× 10 -5 CO 2 (Kuss and Schneider, 2004) warm layer cool skin total CO 2 (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2006) 5. 09× 10 -3 1. 21× 10 -2 1. 18× 10 -2 Others 1× 10 -3 -9× 10 -3 (Foltescu et al. , 1996) 1. 5× 10 -2 -2. 1× 10 -2 (Raymond et al. , 2004) Avg bias* (%) Max bias (%) Error (%) route 1 (solubility) route 2 (ra, rb) -4. 3 1. 5 1. 1 -37. 0 11. 1 0 0 0 100 100 2. 66× 10 -5 5. 6× 10 -5 (Wanninkhof, 2002) 8. 13× 10 -4 7. 83× 10 -5 -1. 8 0. 5 -13. 5 2. 4 96. 9 98. 1 98. 0 3. 1 1. 9 2. 0 3. 71× 10 -5 1. 11× 10 -4 8. 94× 10 -5 3. 66× 10 -5 1. 12× 10 -4 8. 99× 10 -5 -1. 8 0. 6 0. 5 -13. 5 2. 4 95. 9 97. 8 4. 1 2. 2 warm layer cool skin total 1. 20× 10 -3 3. 26× 10 -3 3. 15× 10 -3 1. 17× 1033. 31× 10 -3 3. 20× 10 -3 -2. 3 1. 7 1. 0 -17. 7 3. 8 68. 2 73. 6 73. 4 31. 8 26. 4 26. 6 O 3 warm layer cool skin total 2. 10× 10 -4 2. 99× 10 -4 2. 93× 10 -4 2. 08× 10 -4 1. 6× 10 -4 -7. 8× 10 -4 (Chang et al. , 2004) 3. 01× 10 -4 7. 0× 10 -4 (Hauglustaine et al. , 1994) 2. 97× 10 -4 7. 5× 10 -4 (Muller, 1992) -0. 8 0. 9 0. 4 -5. 4 3. 1 72. 9 89. 5 88. 1 27. 1 10. 5 11. 9 NO 2 warm layer cool skin total 9. 21× 10 -6 2. 64× 10 -5 2. 50× 10 -5 9. 04× 10 -6 2. 0× 10 -4 (Hauglustaine et al. , 1994) 2. 69× 10 -5 2. 53× 10 -5 -1. 9 2. 0 1. 0 -16. 0 4. 8 97. 7 2. 3 NO warm layer cool skin total 1. 51× 10 -6 4. 36× 10 -6 4. 14× 10 -6 1. 49× 10 -6 3. 0× 10 -5 (Hauglustaine et al. , 1994) 4. 44× 10 -6 4. 28× 10 -6 -1. 5 1. 7 0. 8 -12. 6 3. 7 99. 8 99. 9 0. 2 0. 1 CO warm layer cool skin total 7. 49× 10 -7 2. 17× 10 -6 2. 09× 10 -6 7. 39× 10 -7 0 (Hauglustaine et al. , 1994) 2. 20× 10 -6 2. 13× 10 -6 -1. 4 1. 7 0. 8 -12. 1 3. 5 100 100 0 Conclusion It was observed that the skin sea surface temperature is different from the bulk sea surface temperature by about a few tenths of a degree Celsius. It was found that when the warm layer occurs, the dry deposition velocity estimated by using BSST is underestimated within the range of 0. 8 – 4. 3 %; under the other conditions (i. . e. , only cool skin occurring), the dry deposition velocity estimated by using BSST is overestimated within the range of 0. 5 – 2. 0 %, varying with pollutants, along the route of the research ship. There are two mechanisms which can change the deposition rate due to the error in using BSST. Firstly, the solubility of a gas pollutant is a function of sea temperature. Secondly, the difference of the estimated turbulent heat fluxes, determined between using BSST and SSST, causes a difference in the estimated stabilities, aerodynamic resistances and, consequently, dry deposition rates. Additionally, it is found that under the warm-layer dominated condition, latent heat flux, sensible heat flux and surface upward longwave radiation were underestimated by 14 W m-2, 3 W m-2 and 4 W m-2, respectively. That is, the net surface ground heat flux absorbed by sea water was overestimated by 21 W m-2. In contrast, under the cool-skin only condition, using BSST as SST, latent heat flux, sensible heat flux and surface upward longwave radiation were overestimated by 16 W m-2, 4 W m-2 and 1 W m-2, respectively. That is, the net surface ground heat flux absorbed by sea water was underestimated by 21 W m-2.