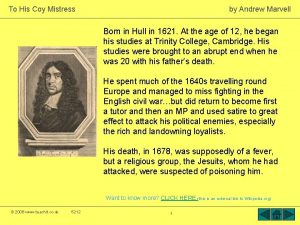

Andrew Marvell To His Coy Mistress Contin Danielis

- Slides: 10

Andrew Marvell To His Coy Mistress Contin, Danielis, De Paoli

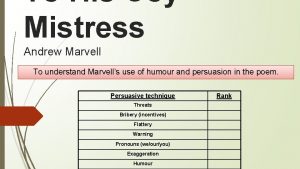

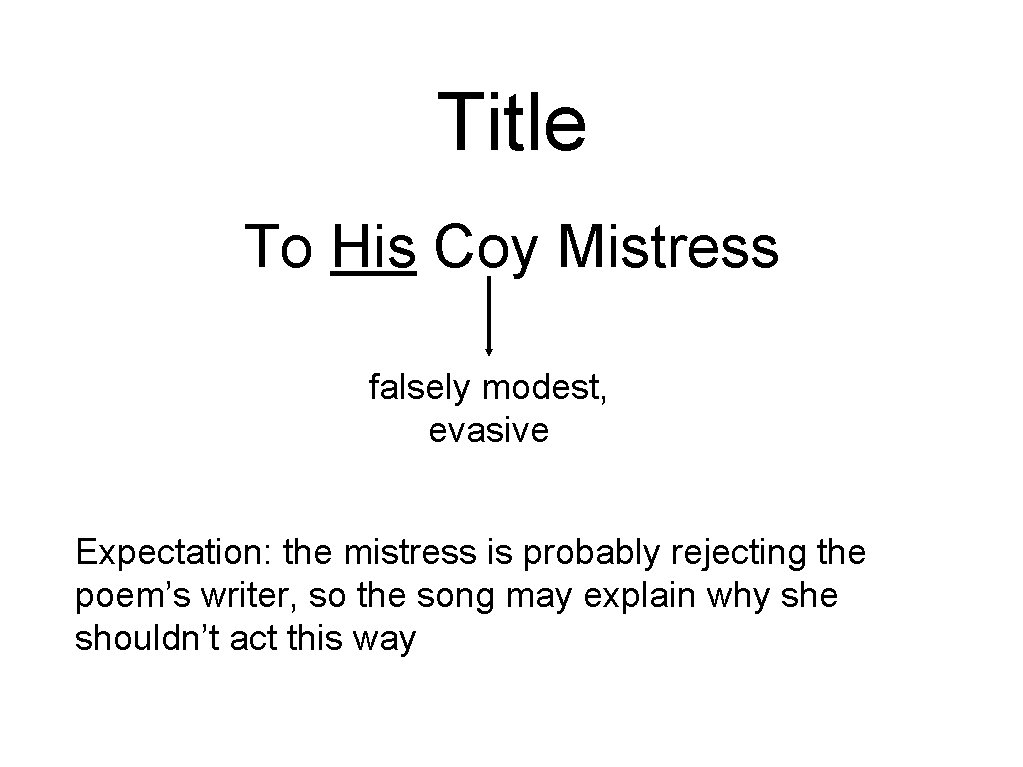

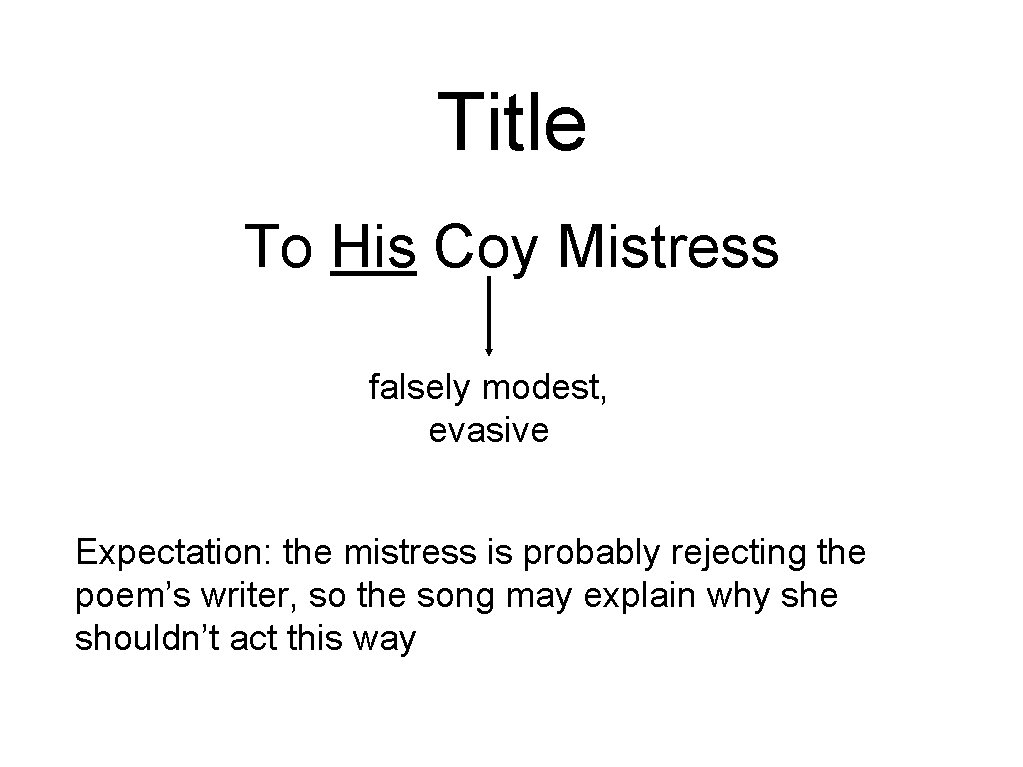

Title To His Coy Mistress falsely modest, evasive Expectation: the mistress is probably rejecting the poem’s writer, so the song may explain why she shouldn’t act this way

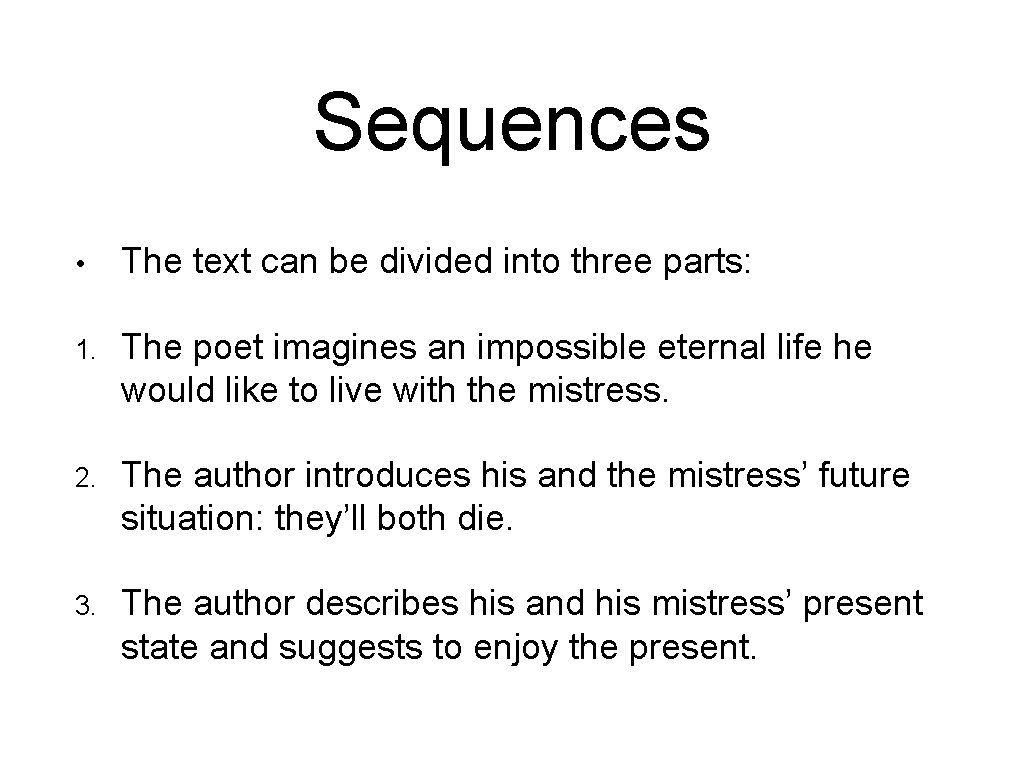

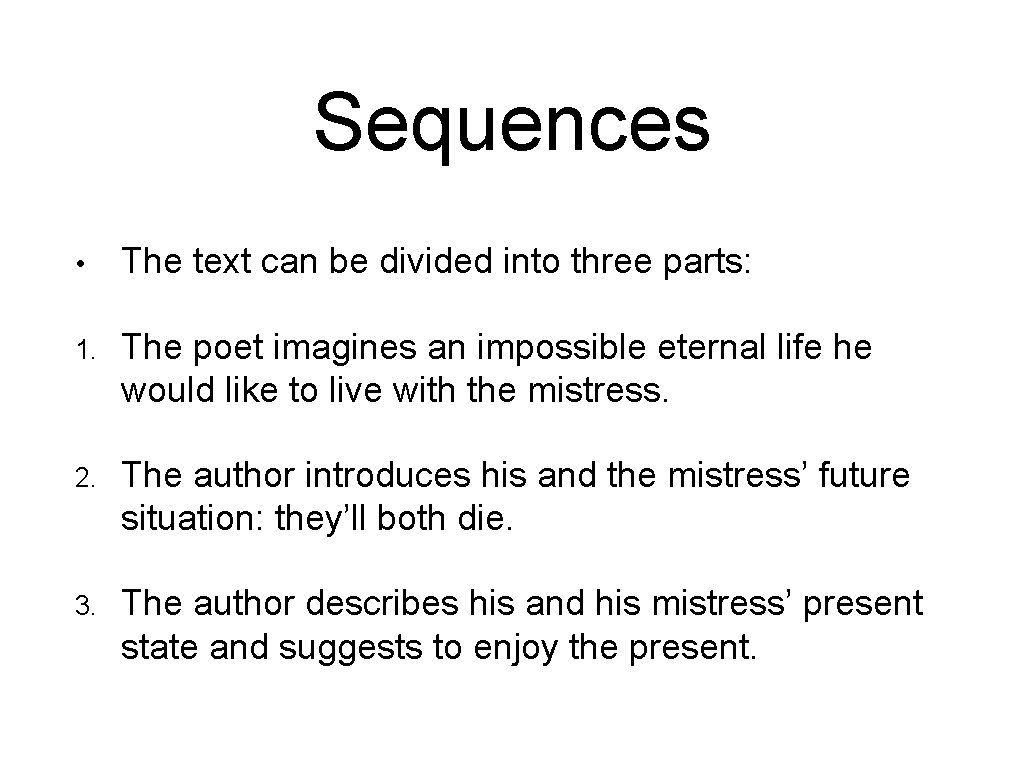

Sequences • The text can be divided into three parts: 1. The poet imagines an impossible eternal life he would like to live with the mistress. 2. The author introduces his and the mistress’ future situation: they’ll both die. 3. The author describes his and his mistress’ present state and suggests to enjoy the present.

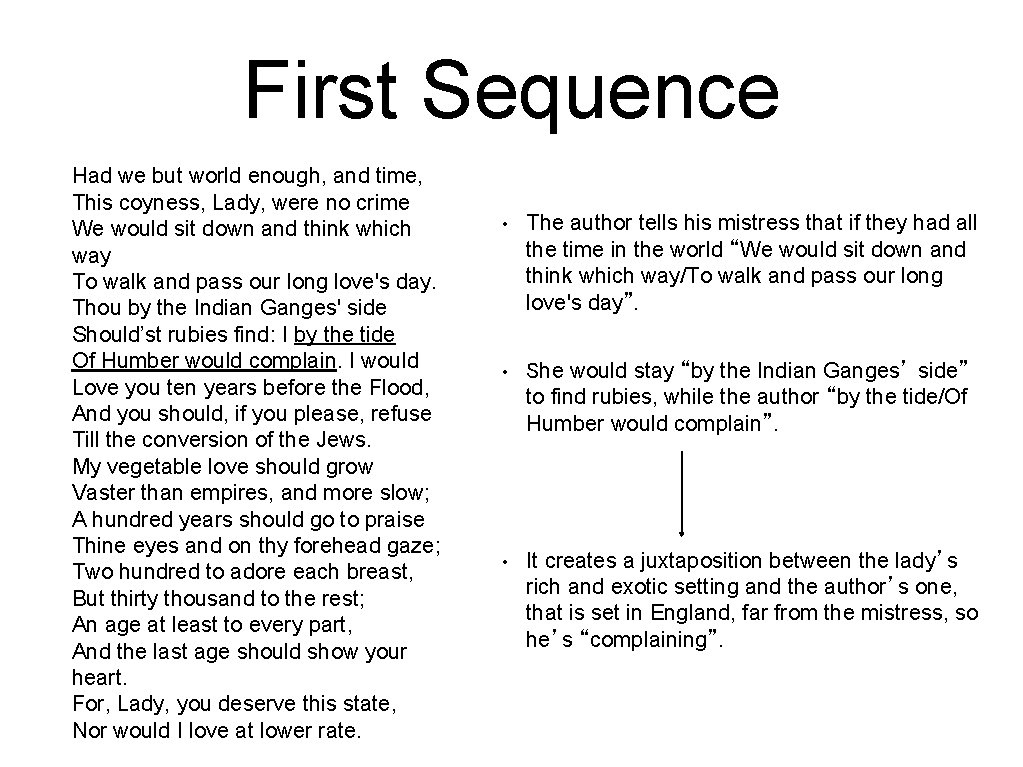

First Sequence Had we but world enough, and time, This coyness, Lady, were no crime We would sit down and think which way To walk and pass our long love's day. Thou by the Indian Ganges' side Should’st rubies find: I by the tide Of Humber would complain. I would Love you ten years before the Flood, And you should, if you please, refuse Till the conversion of the Jews. My vegetable love should grow Vaster than empires, and more slow; A hundred years should go to praise Thine eyes and on thy forehead gaze; Two hundred to adore each breast, But thirty thousand to the rest; An age at least to every part, And the last age should show your heart. For, Lady, you deserve this state, Nor would I love at lower rate. • The author tells his mistress that if they had all the time in the world “We would sit down and think which way/To walk and pass our long love's day”. • She would stay “by the Indian Ganges’ side” to find rubies, while the author “by the tide/Of Humber would complain”. • It creates a juxtaposition between the lady’s rich and exotic setting and the author’s one, that is set in England, far from the mistress, so he’s “complaining”.

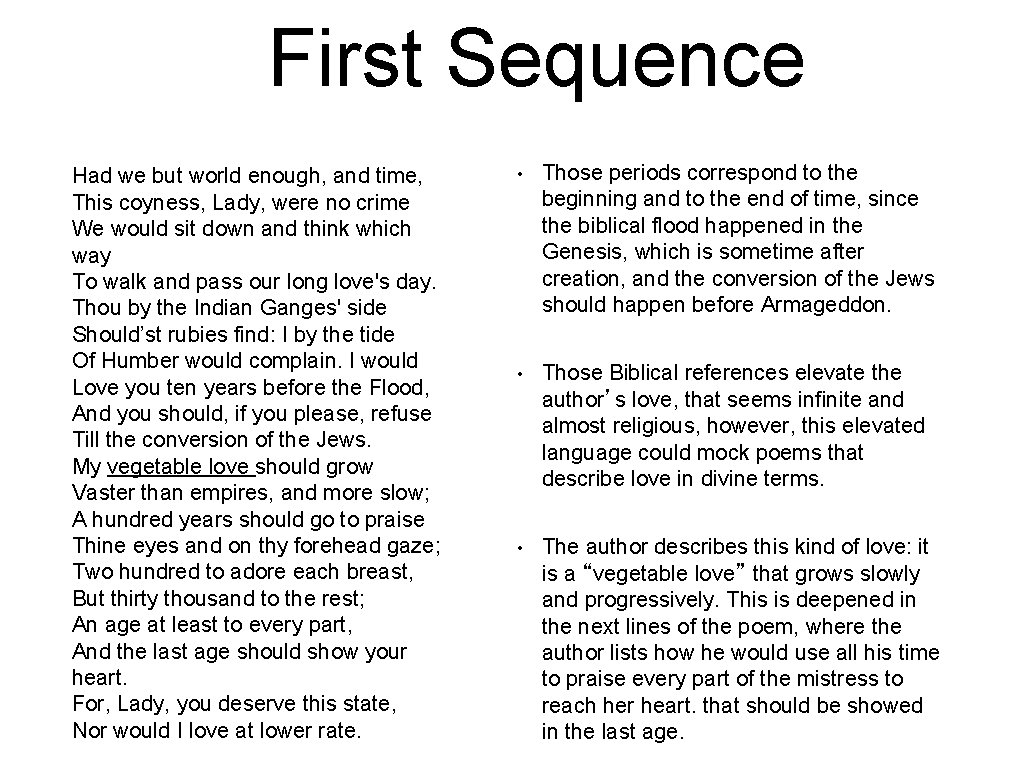

First Sequence Had we but world enough, and time, This coyness, Lady, were no crime We would sit down and think which way To walk and pass our long love's day. Thou by the Indian Ganges' side Should’st rubies find: I by the tide Of Humber would complain. I would Love you ten years before the Flood, And you should, if you please, refuse Till the conversion of the Jews. My vegetable love should grow Vaster than empires, and more slow; A hundred years should go to praise Thine eyes and on thy forehead gaze; Two hundred to adore each breast, But thirty thousand to the rest; An age at least to every part, And the last age should show your heart. For, Lady, you deserve this state, Nor would I love at lower rate. • Those periods correspond to the beginning and to the end of time, since the biblical flood happened in the Genesis, which is sometime after creation, and the conversion of the Jews should happen before Armageddon. • Those Biblical references elevate the author’s love, that seems infinite and almost religious, however, this elevated language could mock poems that describe love in divine terms. • The author describes this kind of love: it is a “vegetable love” that grows slowly and progressively. This is deepened in the next lines of the poem, where the author lists how he would use all his time to praise every part of the mistress to reach her heart. that should be showed in the last age.

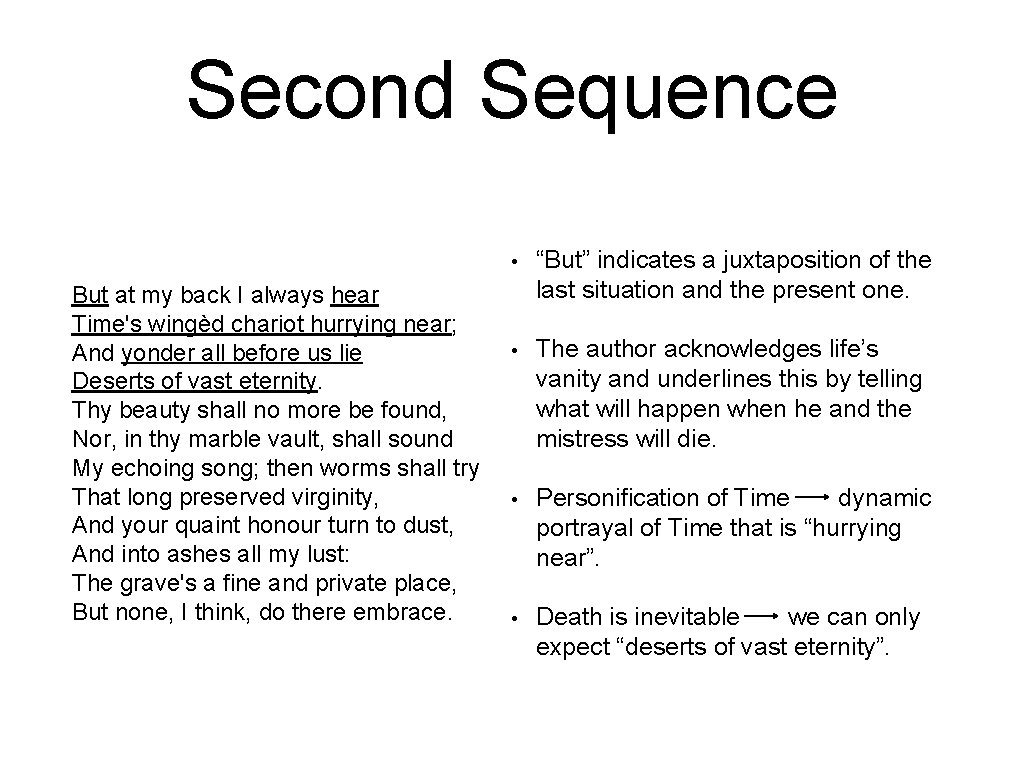

Second Sequence But at my back I always hear Time's wingèd chariot hurrying near; And yonder all before us lie Deserts of vast eternity. Thy beauty shall no more be found, Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound My echoing song; then worms shall try That long preserved virginity, And your quaint honour turn to dust, And into ashes all my lust: The grave's a fine and private place, But none, I think, do there embrace. • “But” indicates a juxtaposition of the last situation and the present one. • The author acknowledges life’s vanity and underlines this by telling what will happen when he and the mistress will die. • Personification of Time dynamic portrayal of Time that is “hurrying near”. • Death is inevitable we can only expect “deserts of vast eternity”.

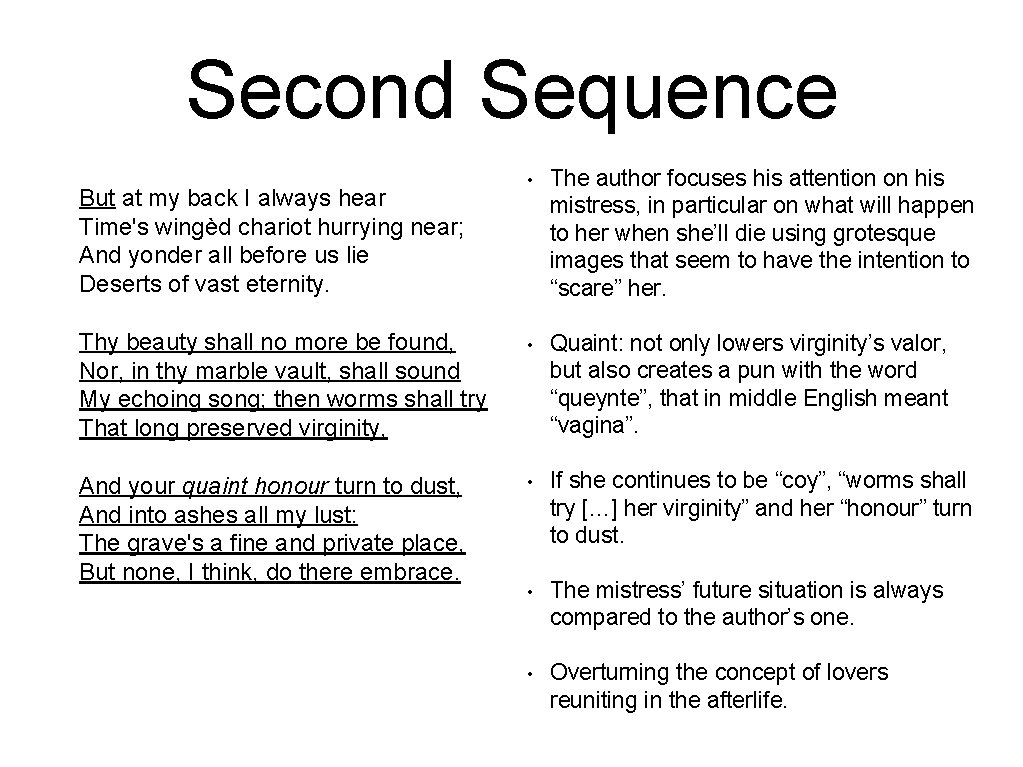

Second Sequence • The author focuses his attention on his mistress, in particular on what will happen to her when she’ll die using grotesque images that seem to have the intention to “scare” her. Thy beauty shall no more be found, Nor, in thy marble vault, shall sound My echoing song; then worms shall try That long preserved virginity, • Quaint: not only lowers virginity’s valor, but also creates a pun with the word “queynte”, that in middle English meant “vagina”. And your quaint honour turn to dust, And into ashes all my lust: The grave's a fine and private place, But none, I think, do there embrace. • If she continues to be “coy”, “worms shall try […] her virginity” and her “honour” turn to dust. • The mistress’ future situation is always compared to the author’s one. • Overturning the concept of lovers reuniting in the afterlife. But at my back I always hear Time's wingèd chariot hurrying near; And yonder all before us lie Deserts of vast eternity.

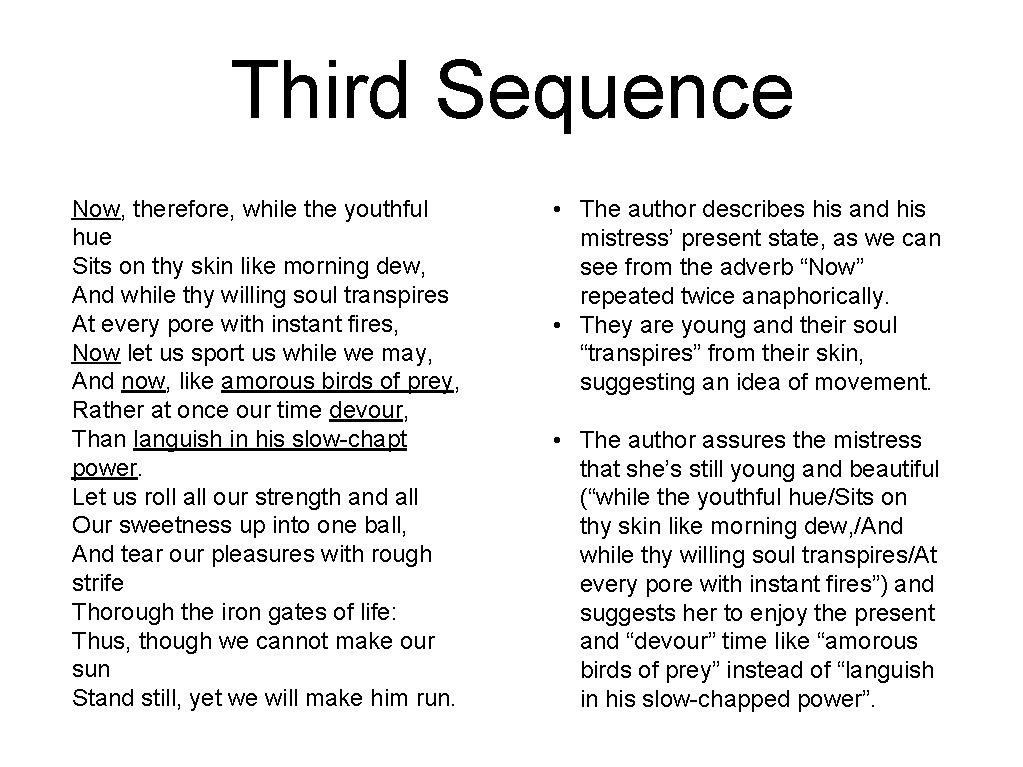

Third Sequence Now, therefore, while the youthful hue Sits on thy skin like morning dew, And while thy willing soul transpires At every pore with instant fires, Now let us sport us while we may, And now, like amorous birds of prey, Rather at once our time devour, Than languish in his slow-chapt power. Let us roll all our strength and all Our sweetness up into one ball, And tear our pleasures with rough strife Thorough the iron gates of life: Thus, though we cannot make our sun Stand still, yet we will make him run. • The author describes his and his mistress’ present state, as we can see from the adverb “Now” repeated twice anaphorically. • They are young and their soul “transpires” from their skin, suggesting an idea of movement. • The author assures the mistress that she’s still young and beautiful (“while the youthful hue/Sits on thy skin like morning dew, /And while thy willing soul transpires/At every pore with instant fires”) and suggests her to enjoy the present and “devour” time like “amorous birds of prey” instead of “languish in his slow-chapped power”.

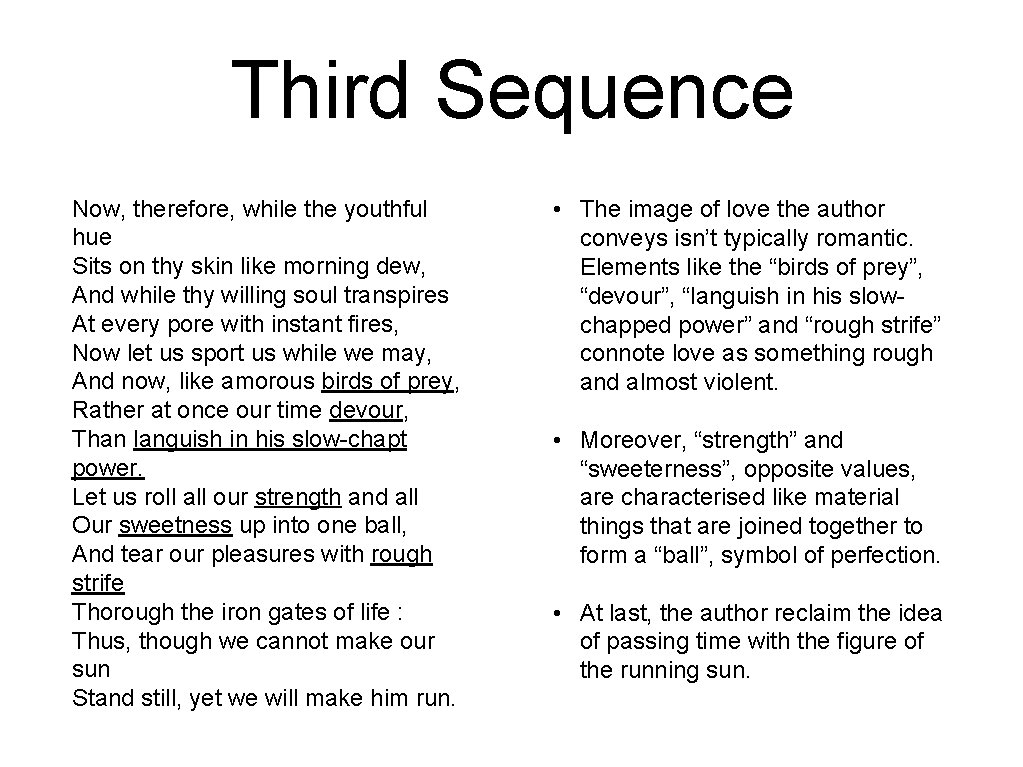

Third Sequence Now, therefore, while the youthful hue Sits on thy skin like morning dew, And while thy willing soul transpires At every pore with instant fires, Now let us sport us while we may, And now, like amorous birds of prey, Rather at once our time devour, Than languish in his slow-chapt power. Let us roll all our strength and all Our sweetness up into one ball, And tear our pleasures with rough strife Thorough the iron gates of life : Thus, though we cannot make our sun Stand still, yet we will make him run. • The image of love the author conveys isn’t typically romantic. Elements like the “birds of prey”, “devour”, “languish in his slowchapped power” and “rough strife” connote love as something rough and almost violent. • Moreover, “strength” and “sweeterness”, opposite values, are characterised like material things that are joined together to form a “ball”, symbol of perfection. • At last, the author reclaim the idea of passing time with the figure of the running sun.

Conclusions • This isn’t just a love poem but a reflection on time and death that bases on the concept of “carpe diem”. • It’s no use to grasp on the concept of “honour”, since it will be useless in death. • The only thing people can do is enjoy the present like “amorous birds of prey” and make time run.