You are what you eat The headhunter is

- Slides: 29

You are what you eat! “The headhunter is not content merely to possess the skull, but opens it and takes out the brain, which he eats in order by this means to acquire the wisdom and skill of his foe” GHR von Koenigswald “Diet underlies many of the behavioural and ecological differences that separate species, and so is important in defining niche, with all its implications for the ecology and evolution of extinct forms” Peter Ungar, 2003 Dr. Susannah Thorpe, Rm W 126 Email: S. K. Thorpe@bham. ac. uk

Homo erectus • Glacial conditions • Cave / sapling shelters • Fire: • warmth • protection • cooking?

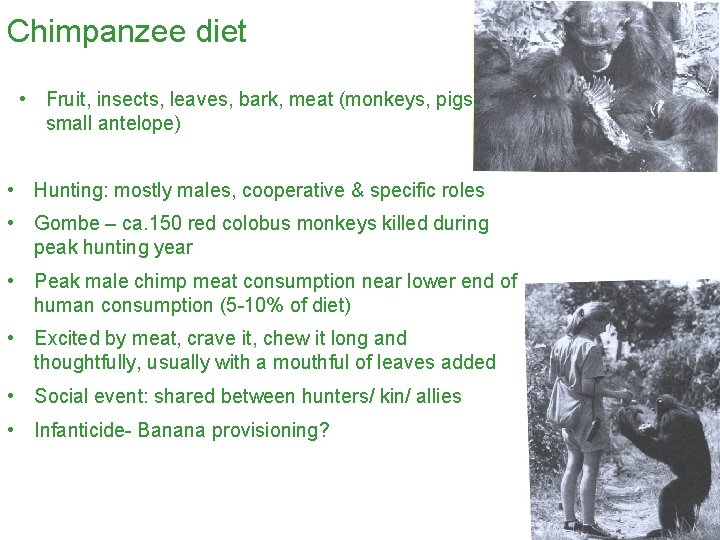

Chimpanzee diet • Fruit, insects, leaves, bark, meat (monkeys, pigs, small antelope) • Hunting: mostly males, cooperative & specific roles • Gombe – ca. 150 red colobus monkeys killed during peak hunting year • Peak male chimp meat consumption near lower end of human consumption (5 -10% of diet) • Excited by meat, crave it, chew it long and thoughtfully, usually with a mouthful of leaves added • Social event: shared between hunters/ kin/ allies • Infanticide- Banana provisioning?

Chimpanzees: medicinal plants • Medicinal plants: pith or leaves of plants with medicinal properties – know when they need it – knowledge to select particular species that are not part of normal diet – Tongwa people eat the same plants for medicinal use – unpalatable, chimps swallow them like pills rather than chewing the leaves – Contain an antibiotic against bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasitic worms

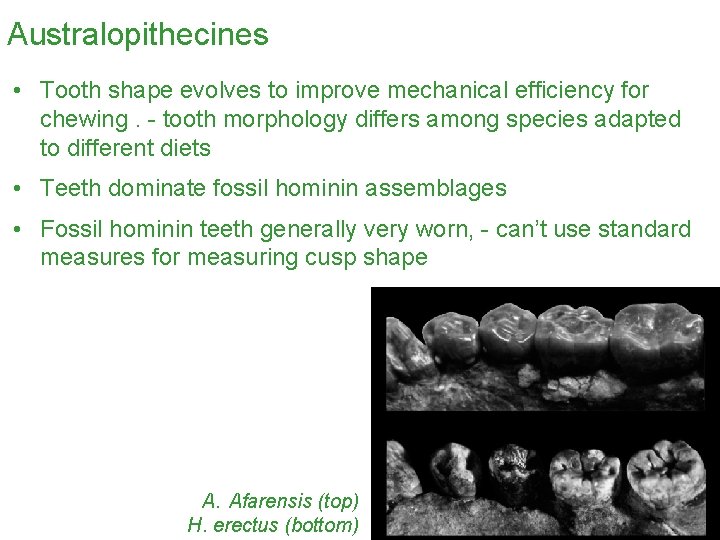

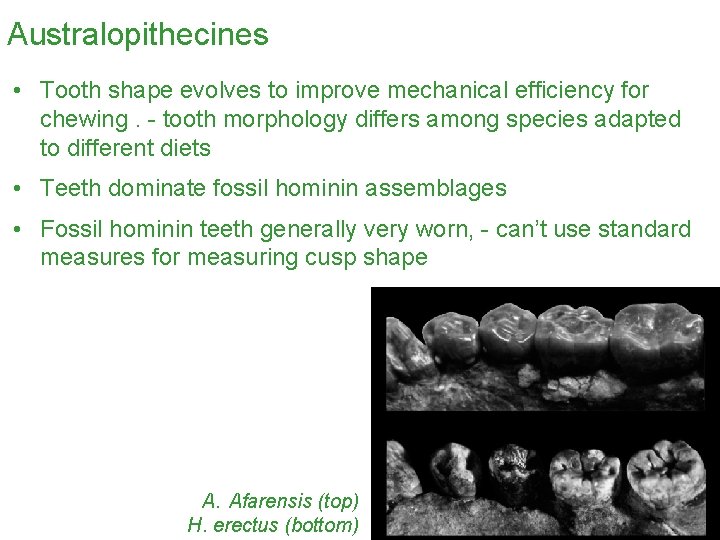

Australopithecines • Tooth shape evolves to improve mechanical efficiency for chewing. - tooth morphology differs among species adapted to different diets • Teeth dominate fossil hominin assemblages • Fossil hominin teeth generally very worn, - can’t use standard measures for measuring cusp shape A. Afarensis (top) H. erectus (bottom)

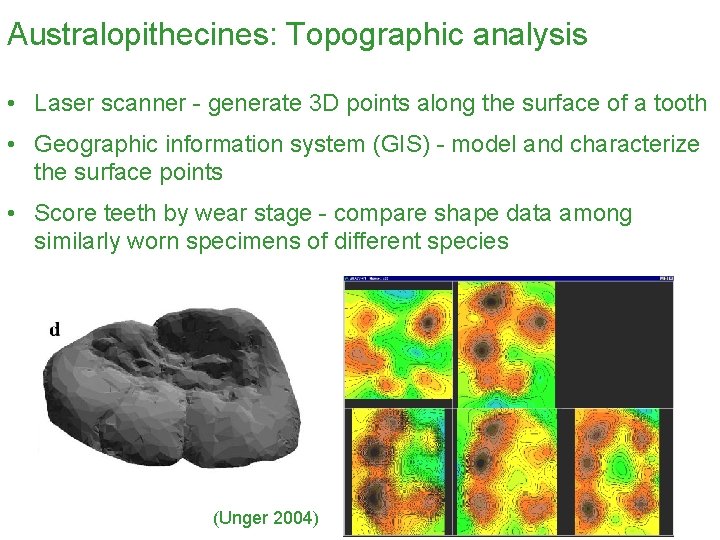

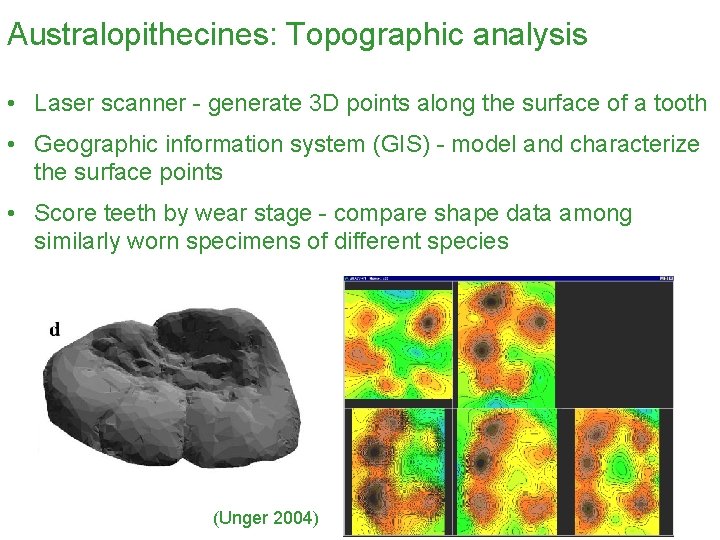

Australopithecines: Topographic analysis • Laser scanner - generate 3 D points along the surface of a tooth • Geographic information system (GIS) - model and characterize the surface points • Score teeth by wear stage - compare shape data among similarly worn specimens of different species (Unger 2004)

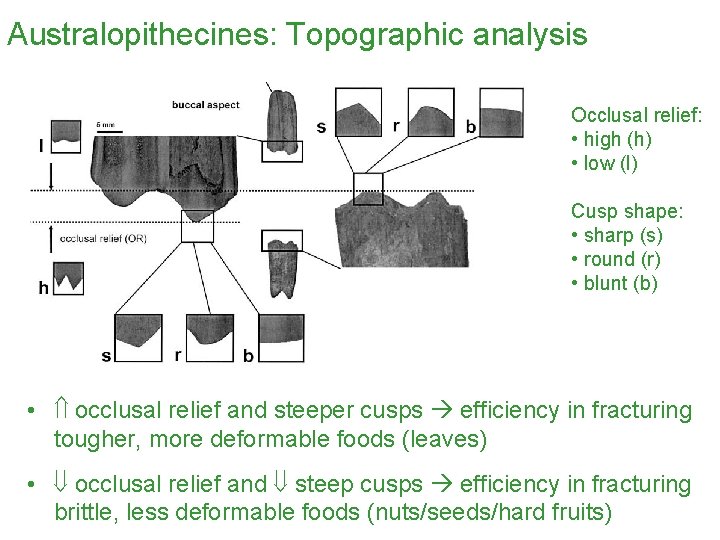

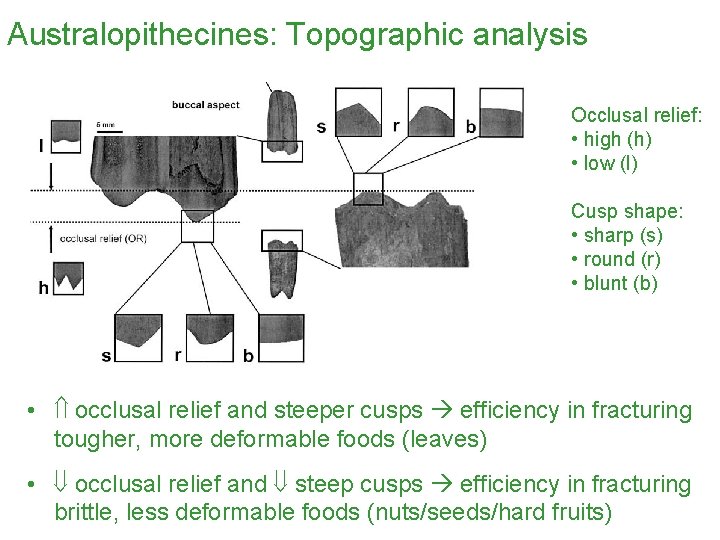

Australopithecines: Topographic analysis Occlusal relief: • high (h) • low (l) Cusp shape: • sharp (s) • round (r) • blunt (b) • occlusal relief and steeper cusps efficiency in fracturing tougher, more deformable foods (leaves) • occlusal relief and steep cusps efficiency in fracturing brittle, less deformable foods (nuts/seeds/hard fruits)

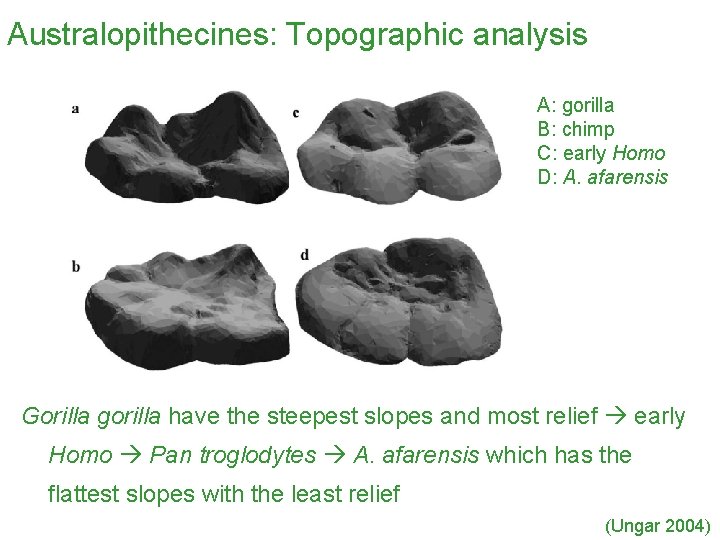

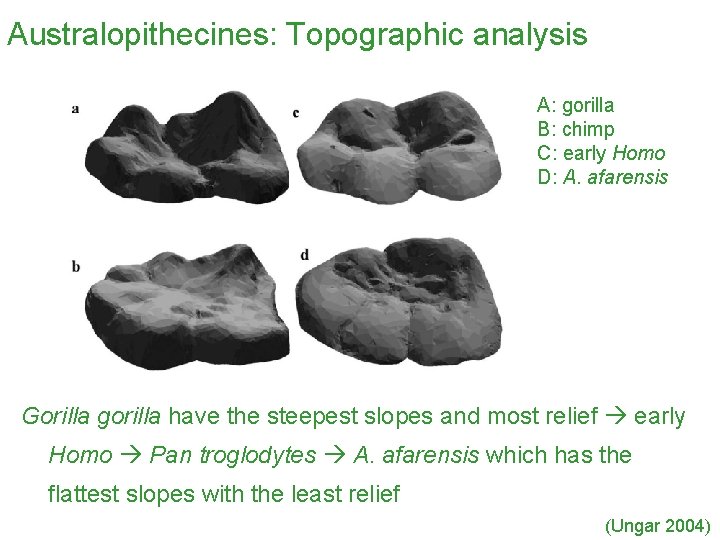

Australopithecines: Topographic analysis A: gorilla B: chimp C: early Homo D: A. afarensis Gorilla gorilla have the steepest slopes and most relief early Homo Pan troglodytes A. afarensis which has the flattest slopes with the least relief (Ungar 2004)

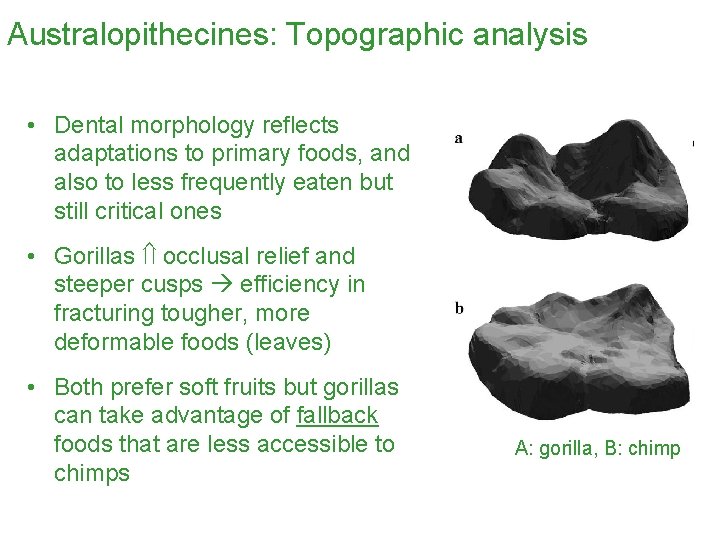

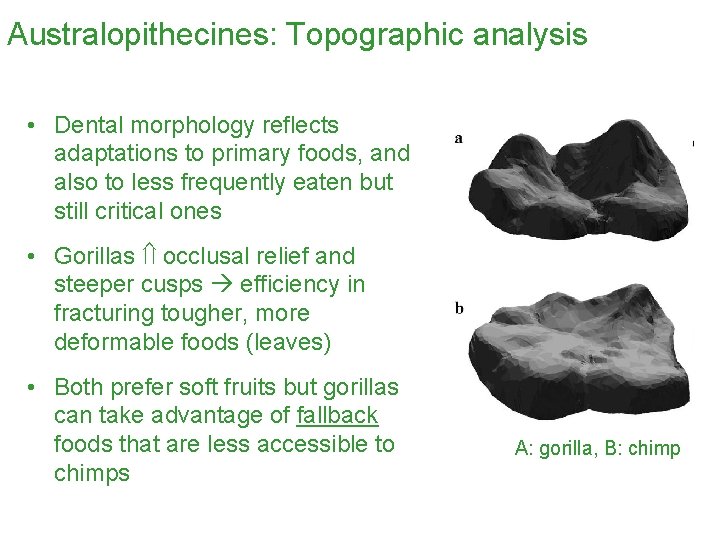

Australopithecines: Topographic analysis • Dental morphology reflects adaptations to primary foods, and also to less frequently eaten but still critical ones • Gorillas occlusal relief and steeper cusps efficiency in fracturing tougher, more deformable foods (leaves) • Both prefer soft fruits but gorillas can take advantage of fallback foods that are less accessible to chimps A: gorilla, B: chimp

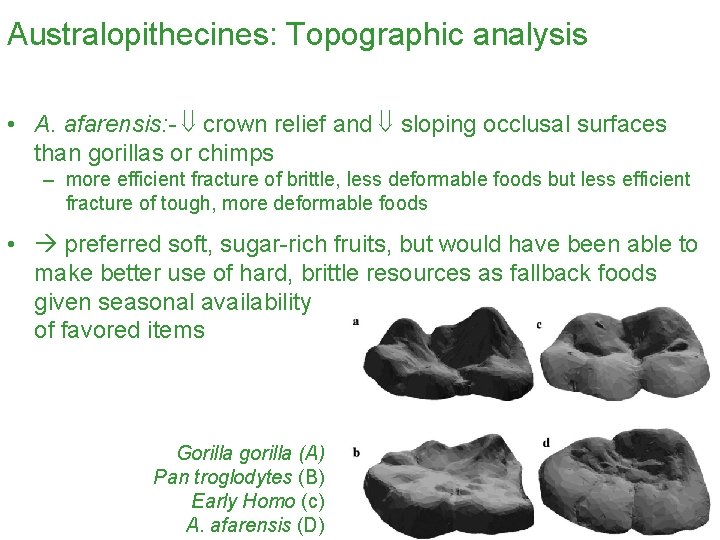

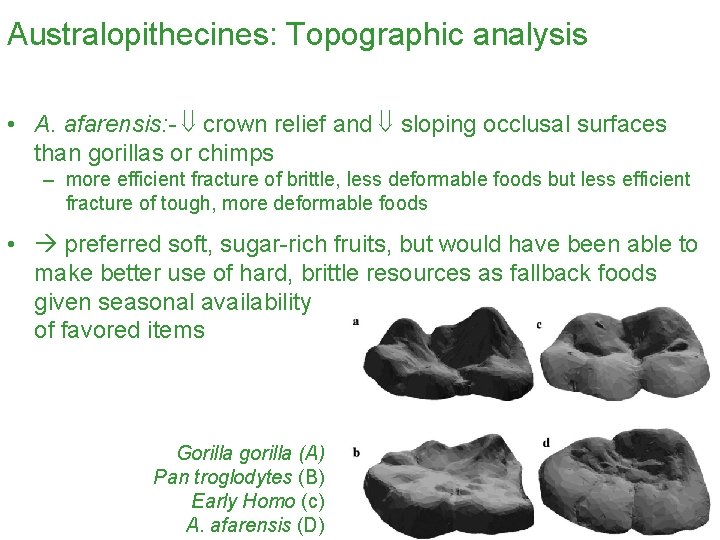

Australopithecines: Topographic analysis • A. afarensis: - crown relief and sloping occlusal surfaces than gorillas or chimps – more efficient fracture of brittle, less deformable foods but less efficient fracture of tough, more deformable foods • preferred soft, sugar-rich fruits, but would have been able to make better use of hard, brittle resources as fallback foods given seasonal availability of favored items Gorilla gorilla (A) Pan troglodytes (B) Early Homo (c) A. afarensis (D)

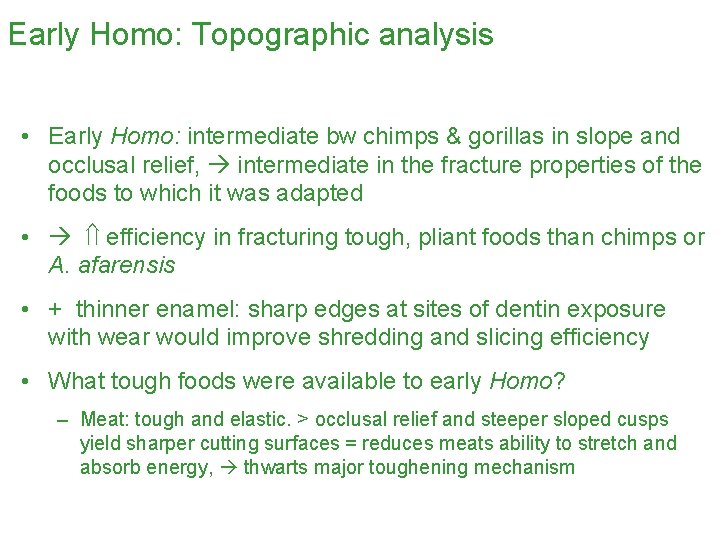

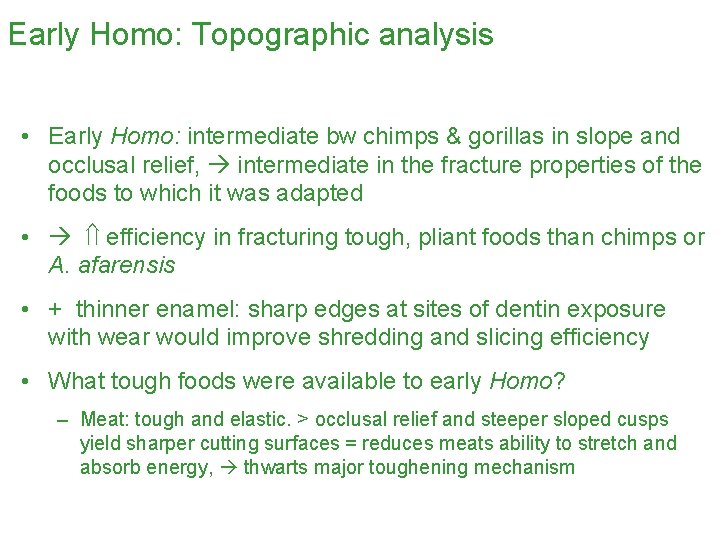

Early Homo: Topographic analysis • Early Homo: intermediate bw chimps & gorillas in slope and occlusal relief, intermediate in the fracture properties of the foods to which it was adapted • efficiency in fracturing tough, pliant foods than chimps or A. afarensis • + thinner enamel: sharp edges at sites of dentin exposure with wear would improve shredding and slicing efficiency • What tough foods were available to early Homo? – Meat: tough and elastic. > occlusal relief and steeper sloped cusps yield sharper cutting surfaces = reduces meats ability to stretch and absorb energy, thwarts major toughening mechanism

Paranthropus boisei • Ungar: A. africanus & Paranthropus lived at different times at Sterkfontein • A. Africanus: steeper molar cusps • Paranthropus: large, crushing teeth (roots/seeds) • Did climatic swings lead to reduction in food sources for Paranthropus?

Did H. erectus hunt or scavenge? • more food per square mile of the African savannah than plant food • more effective energy source – venison: 572 cals per 100 g – fruit/veg <100 cals per 100 g • Reduced risk of seasonality, esp. in Northern temperate zones

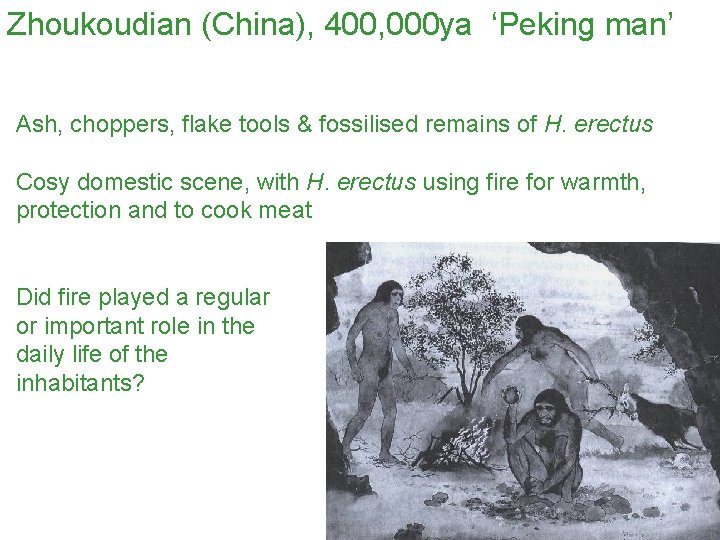

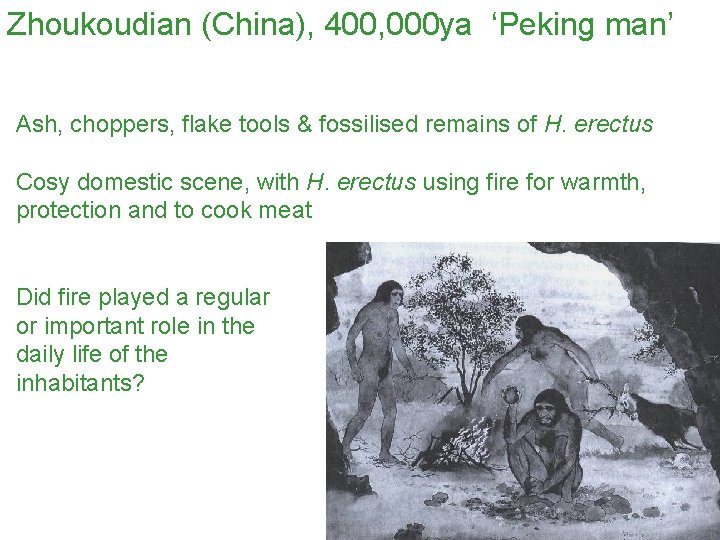

Zhoukoudian (China), 400, 000 ya ‘Peking man’ Ash, choppers, flake tools & fossilised remains of H. erectus Cosy domestic scene, with H. erectus using fire for warmth, protection and to cook meat Did fire played a regular or important role in the daily life of the inhabitants?

Zhoukoudian (China), 400, 000 ya ‘Peking man’ • Certainly some evidence of fire, but Lewis Binford : – Many of the extensive ash layers may be results of the decalcification of massive organic deposits (including bird droppings, bat guana, hyena faeces) – Fires could have been a result of the accidental ignition of the organic material, which then smouldered for some time • Binford found no hearths, or any association between ash, stone tools and H. erectus fossils • So although had all the ingredients of a cosy domestic scene the ingredients were not related

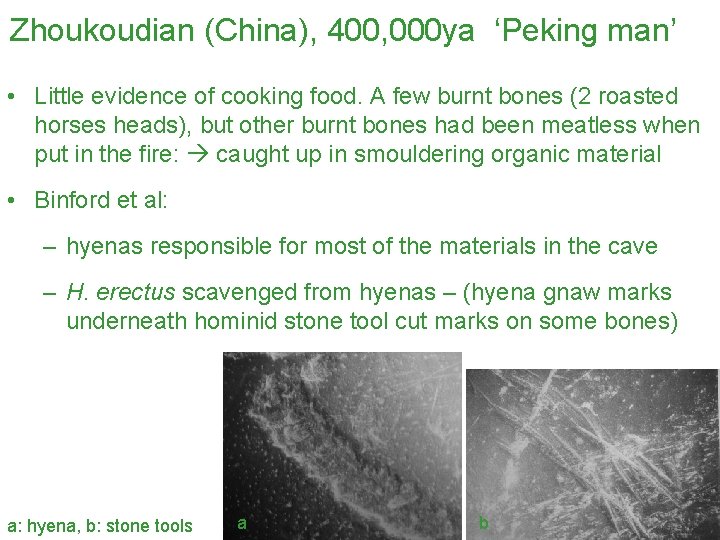

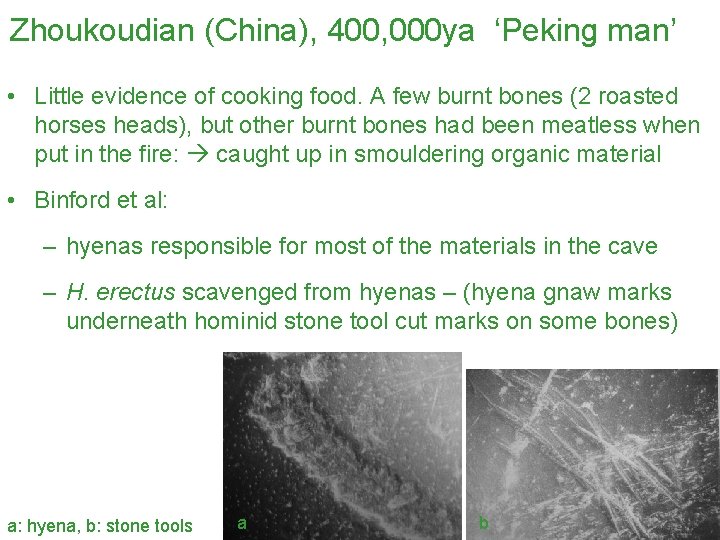

Zhoukoudian (China), 400, 000 ya ‘Peking man’ • Little evidence of cooking food. A few burnt bones (2 roasted horses heads), but other burnt bones had been meatless when put in the fire: caught up in smouldering organic material • Binford et al: – hyenas responsible for most of the materials in the cave – H. erectus scavenged from hyenas – (hyena gnaw marks underneath hominid stone tool cut marks on some bones) a: hyena, b: stone tools a b

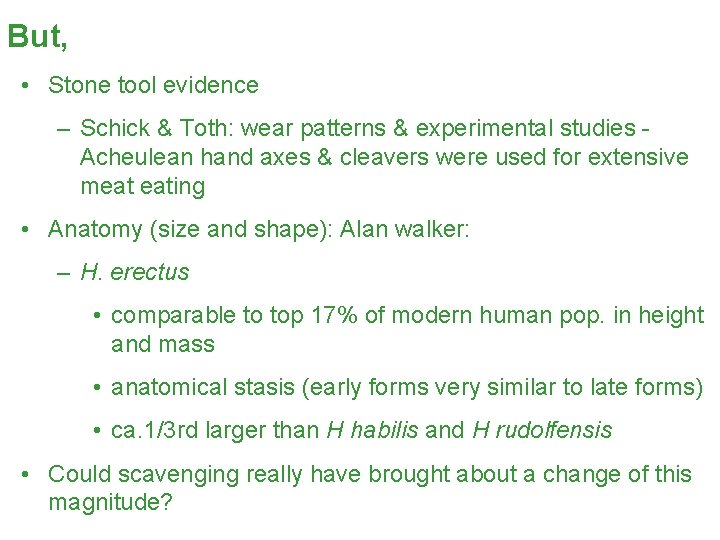

But, • Stone tool evidence – Schick & Toth: wear patterns & experimental studies Acheulean hand axes & cleavers were used for extensive meat eating • Anatomy (size and shape): Alan walker: – H. erectus • comparable to top 17% of modern human pop. in height and mass • anatomical stasis (early forms very similar to late forms) • ca. 1/3 rd larger than H habilis and H rudolfensis • Could scavenging really have brought about a change of this magnitude?

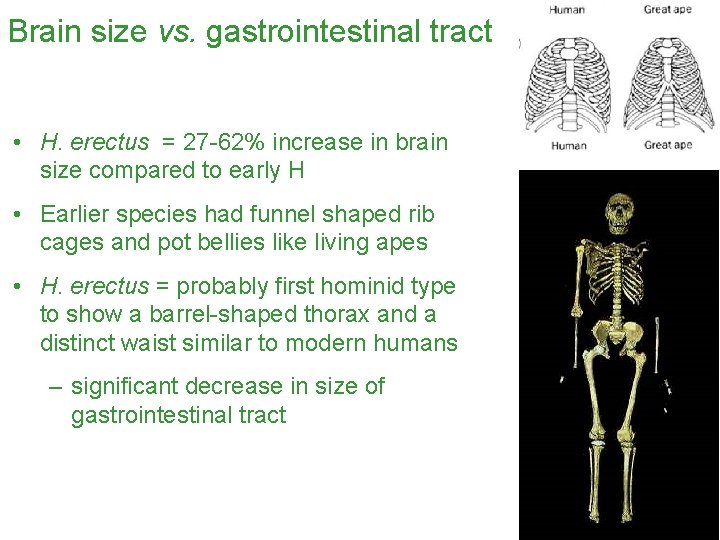

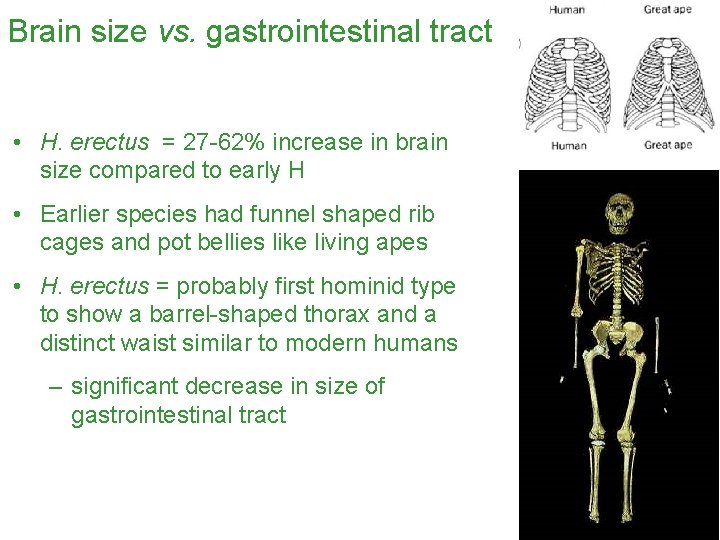

Brain size vs. gastrointestinal tract • H. erectus = 27 -62% increase in brain size compared to early H • Earlier species had funnel shaped rib cages and pot bellies like living apes • H. erectus = probably first hominid type to show a barrel-shaped thorax and a distinct waist similar to modern humans – significant decrease in size of gastrointestinal tract

Mass-specific organ metabolic rates in humans Brain: mass specific metabolic rate c. 9 x average rate for body Liver/gastrointestinal tract: mass specific metabolic rate c. 9. 8 x average rate for body 2 ways to accommodate the increased energy demands of the large brain of HE: • raise the overall basal metabolism rate of the body or • compensate for brain growth by reducing the size of another metabolically expensive organ Organ Metabolic weight in W. Kg-1 (watts per kg) Brain 11. 2 Heart 32. 2 Kidney 23. 3 Liver & gastrointestinal tract 12. 2 Skeletal muscle 0. 5 Lung 6. 7 Skin 0. 3

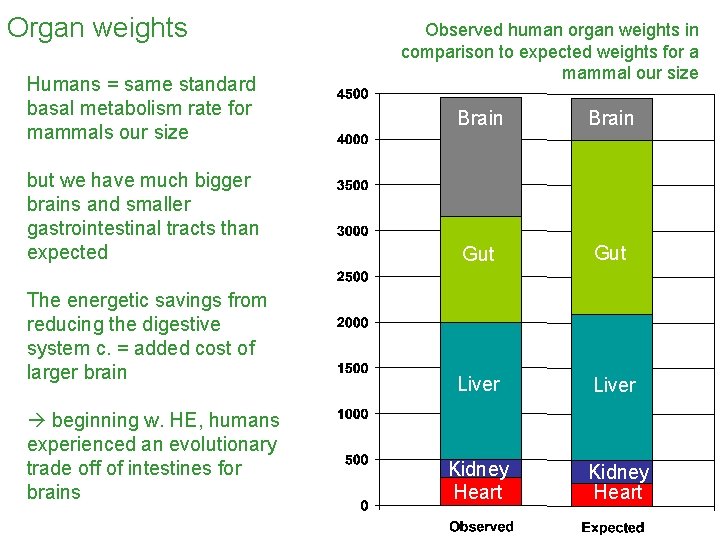

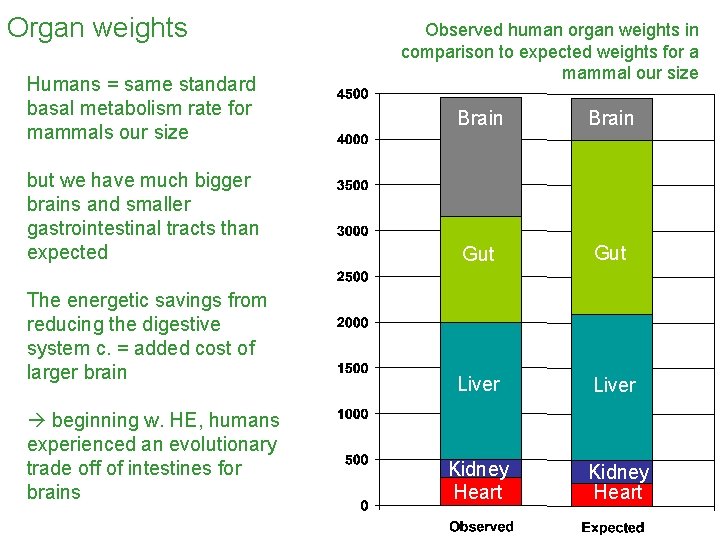

Organ weights Observed human organ weights in comparison to expected weights for a mammal our size but we have much bigger brains and smaller gastrointestinal tracts than expected The energetic savings from reducing the digestive system c. = added cost of larger brain beginning w. HE, humans experienced an evolutionary trade off of intestines for brains Organ weight in grams Humans = same standard basal metabolism rate for mammals our size Brain Gut Liver Kidney Heart

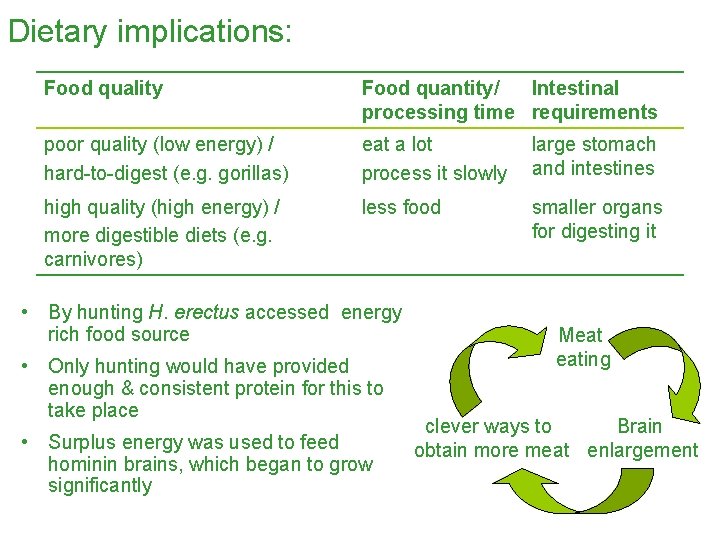

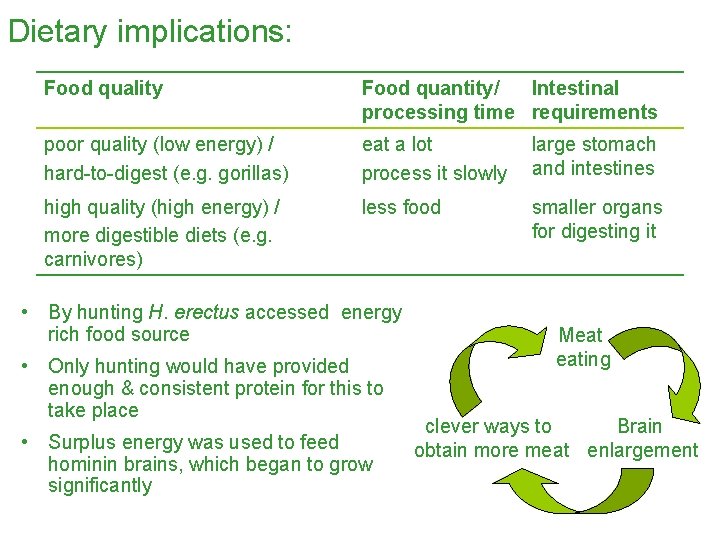

Dietary implications: Food quality Food quantity/ Intestinal processing time requirements poor quality (low energy) / hard-to-digest (e. g. gorillas) eat a lot process it slowly large stomach and intestines high quality (high energy) / more digestible diets (e. g. carnivores) less food smaller organs for digesting it • By hunting H. erectus accessed energy rich food source • Only hunting would have provided enough & consistent protein for this to take place • Surplus energy was used to feed hominin brains, which began to grow significantly Meat eating Brain clever ways to obtain more meat enlargement

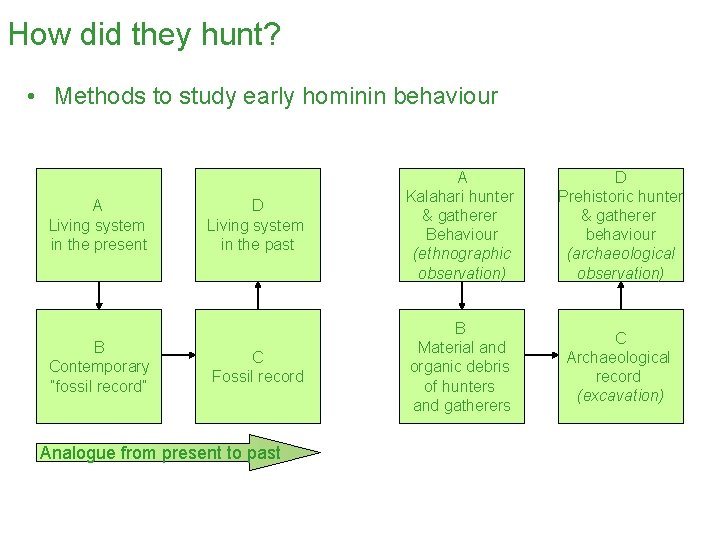

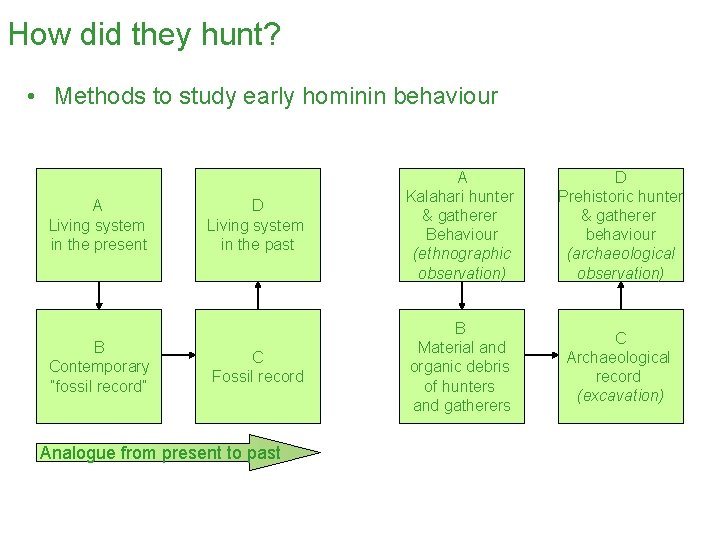

How did they hunt? • Methods to study early hominin behaviour A Living system in the present B Contemporary “fossil record” D Living system in the past A Kalahari hunter & gatherer Behaviour (ethnographic observation) D Prehistoric hunter & gatherer behaviour (archaeological observation) C Fossil record B Material and organic debris of hunters and gatherers C Archaeological record (excavation) Analogue from present to past

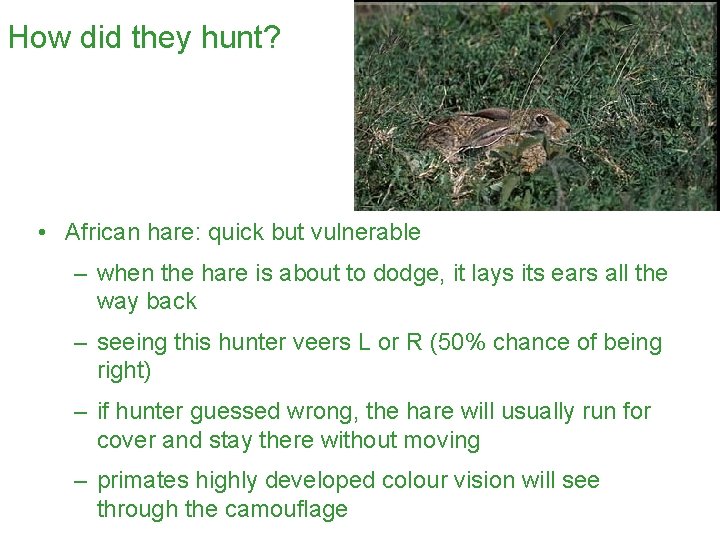

How did they hunt? • African hare: quick but vulnerable – when the hare is about to dodge, it lays its ears all the way back – seeing this hunter veers L or R (50% chance of being right) – if hunter guessed wrong, the hare will usually run for cover and stay there without moving – primates highly developed colour vision will see through the camouflage

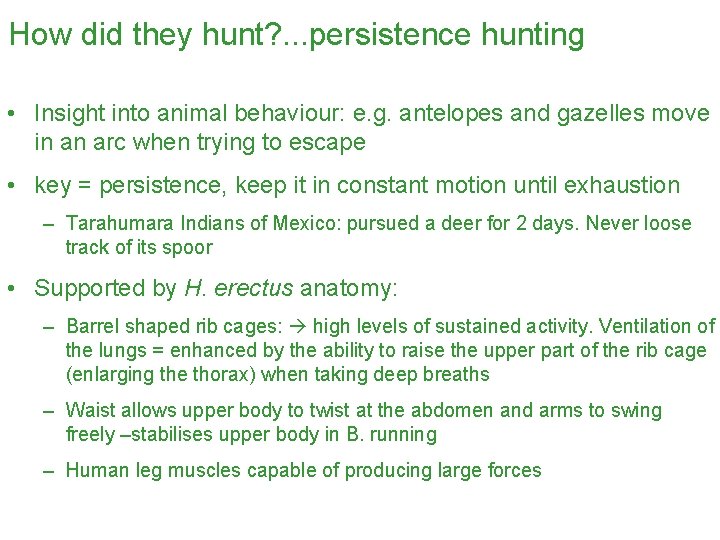

How did they hunt? . . . persistence hunting • Insight into animal behaviour: e. g. antelopes and gazelles move in an arc when trying to escape • key = persistence, keep it in constant motion until exhaustion – Tarahumara Indians of Mexico: pursued a deer for 2 days. Never loose track of its spoor • Supported by H. erectus anatomy: – Barrel shaped rib cages: high levels of sustained activity. Ventilation of the lungs = enhanced by the ability to raise the upper part of the rib cage (enlarging the thorax) when taking deep breaths – Waist allows upper body to twist at the abdomen and arms to swing freely –stabilises upper body in B. running – Human leg muscles capable of producing large forces

How did they hunt? . . . stalking, driving & ambush • Chimps do it • Torralba and Ambrona (Spain, 400 kya, Acheulean) H. erectus hunters driving elephants, horses, deer & rhinos into marshy bogs, killing them & butchering them • Reanalysis (Klein & Shipman 1980’s) hominins (H. erectus/ heidelbergensis) used some of the carcasses (cut marks), no conclusive evidence of actual hunting – ? scavenging the remains of animals that had died naturally or killed by carnivores • 1 st confirmed driving/ambush La Cotte de St. Brelade (Jersey): mammoth and rhino drives (240 kya 125, kya). H. heidelbergensis

Cannibalism • Zoukoudian: human skulls – faceless & had been opened at the base – ? cannibalism - eating the brains of the dead – a lack of ‘humanity’ or culture (spiritual notion that cannibalism could increase their powers) – cannibalism in recent times: the act is nearly always carried out as a ritual not for food – Distinction between dietary and ritual cannibalism = extremely important: its very rare for people to eat other people merely for food

Cannibalism but, … • Lewis Binford: hominin remains are found in deposits containing many other bone fragments, including numerous predators (e. g. Chinese hyena) • The removal of the faces/ destruction of the skull base = what happens when gnawing carnivores chew out the face of their prey • Fossils disappeared in WWII

Cannibalism • Middle awash in Ethiopia: – (Tim White) – curious marks on the skull of H. erectus: forehead of the individual and around and inside the left eye socket – ? scalping & removing tissue from the face • Why would another hominid have done such a thing? • Whether it remains cannibalism, head hunting, or some other behaviour remains a mystery at present • Indicates developed culture

Conclusion • Nomadic - following migrating herds = problems: transporting food and water – No direct evidence – ? bags made of animal hides; containers made of wood, leaves, clay? – Material for toolmaking - probably transported, tools often made at the butchery site – Cooler climates may have stimulated the control/use of fire and the construction of clothing (animal pelts, e. g. Terra Amata: bedding) • All these behaviours can be related to meat eating • Put an even higher premium on continued and better access to meat

Antigentest åre

Antigentest åre Beowulf alliterations

Beowulf alliterations They eat or eats

They eat or eats I would rather eat potatoes than to eat rice yay or nay

I would rather eat potatoes than to eat rice yay or nay People buy me to eat

People buy me to eat Eat meals that are nutritious agree or disagree

Eat meals that are nutritious agree or disagree Tell me what you eat and i shall tell you what you are

Tell me what you eat and i shall tell you what you are You eat what you touch

You eat what you touch “if you eat of the tree, you shall die”

“if you eat of the tree, you shall die” Macromolecules you are what you eat

Macromolecules you are what you eat Nucleic acid test

Nucleic acid test The digestive system you are what you eat worksheet answers

The digestive system you are what you eat worksheet answers Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể

Hát kết hợp bộ gõ cơ thể Frameset trong html5

Frameset trong html5 Bổ thể

Bổ thể Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em

Tỉ lệ cơ thể trẻ em Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào

Voi kéo gỗ như thế nào Glasgow thang điểm

Glasgow thang điểm Hát lên người ơi

Hát lên người ơi Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ đua

Môn thể thao bắt đầu bằng chữ đua Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất

Thế nào là hệ số cao nhất Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

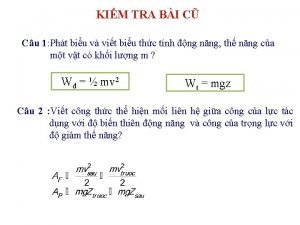

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Công thức tính thế năng

Công thức tính thế năng Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ

Trời xanh đây là của chúng ta thể thơ Mật thư anh em như thể tay chân

Mật thư anh em như thể tay chân Phép trừ bù

Phép trừ bù độ dài liên kết

độ dài liên kết Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới

Các châu lục và đại dương trên thế giới Thể thơ truyền thống

Thể thơ truyền thống Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra

Quá trình desamine hóa có thể tạo ra