YEAR 8 HISTORY ASSIGNMENT Contrasting Journal accounts Due

- Slides: 20

YEAR 8 HISTORY ASSIGNMENT Contrasting Journal accounts

Due dates DATE GIVEN: WEEK 4 DRAFT DUE: WEEK 5 DATE DUE: WEEK 6 MONDAY 11 TH MONDAY 18 TH MONDAY 25 TH

Assessment Outline: ◦ Your task is to write two contrasting journal entries which cover the same historical event. You must write from the perspective of: ◦ (1) A White Settler and ◦ (2) An Indigenous Australian.

The historical event must be ONE of the following: ◦ The Battle of Pinjarra ◦ Myall Creek Massacre ◦ Canning Stock Route ◦ First crossing of the Blue Mountains ◦ The Black Wars

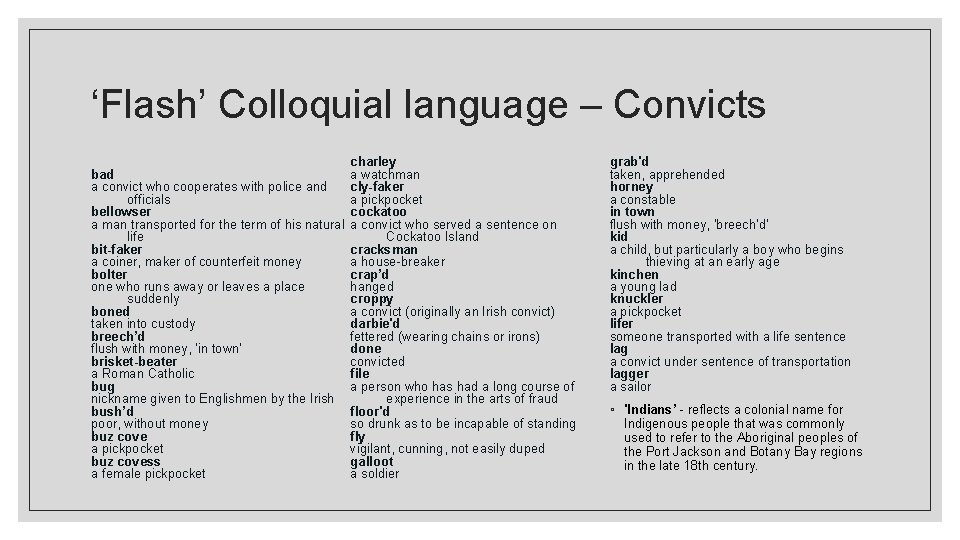

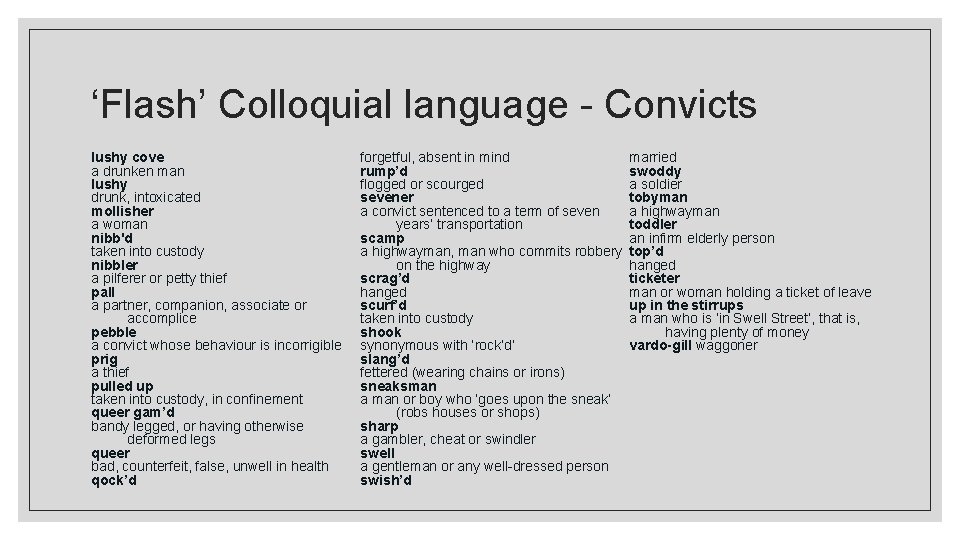

You must: ◦ Put yourself in the shoes of both the Settler and Indigenous Australian (in other words, empathise with them). Consider their respective attitudes, cultures, expectations, histories and what motivates them. ◦ Aim to incorporate colloquial language from the period and respective individual/group to ensure your writing is authentic. ◦ Apply a range of historical facts, terms and concepts ◦ Ensure your chosen event is historically correct. ◦ Use size 12 font, Calibri (or respective) and double space your writing. ◦ Meet the overall word count of 800 words (in total) – 300 -400 words per journal entry. ◦ Provide a reference list, which references all sources of information. Use APA (American Psychological Association), or Harvard format. You must use in-text citation (footnoting) when you refer to a source in your writing.

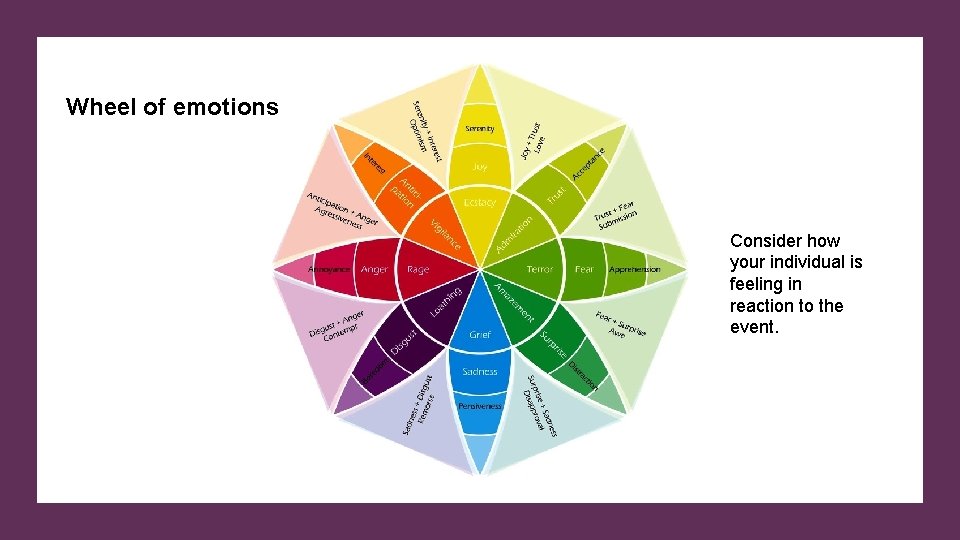

Journal entries – writing tips ◦ A diary entry is a record of an individual’s thoughts, feelings and emotions. ◦ You are to write two journal entries from the perspective of contrasting groups in Colonial Australia in relation to a key event. ◦ Your journal entries should be reflective, and expand on how the individual is feeling in reaction to the event. ◦ You should write in first person, and past tense. ◦ You may spend some time detailing the event (partial recount), though most of it should be your thoughts. ◦ Consider the progression of your feelings in reaction to the event (first, anger? Then sorrow? Confusion? ) ◦ Write in paragraphs! ◦ Choose your moments carefully to show a progression of clarity or a sense of realisation for the individual. ◦ Be as specific as possible to showcase your detailed understanding and appreciation of the event. ◦ Use colloquial language to convey complexity and to demonstrate authenticity in your writing. ◦ Write your journal entry AFTER the event has taken place. ◦ End by revealing your future intentions – what will you do moving forward?

Journal entries – format ◦ Date in the top right-hand corner (E. g. 18 th May 1804) ◦ You may have a subject as a title – e. g. “Pinjarra” ◦ Address line – ‘Dear Diary/Journal’ or: My trusted friend, Let’s turn a new leaf, etc. ◦ Paragraph your ideas. ◦ End with a sign off and your name – ‘I’ll write again soon, Sam’

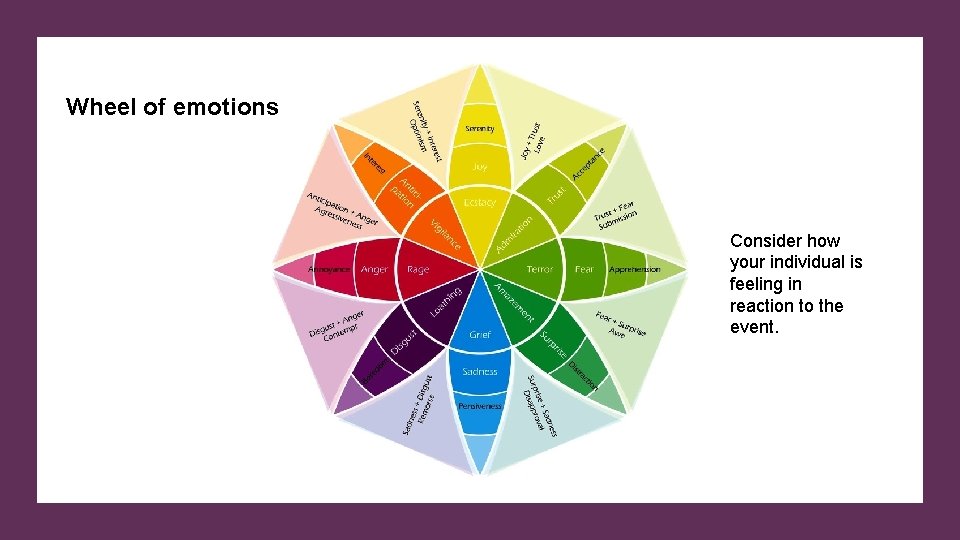

Wheel of emotions Consider how your individual is feeling in reaction to the event.

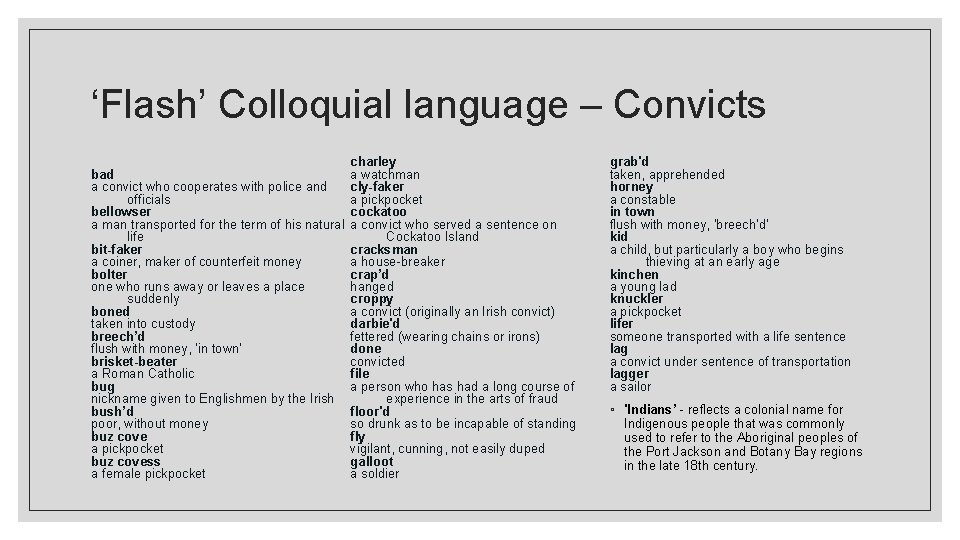

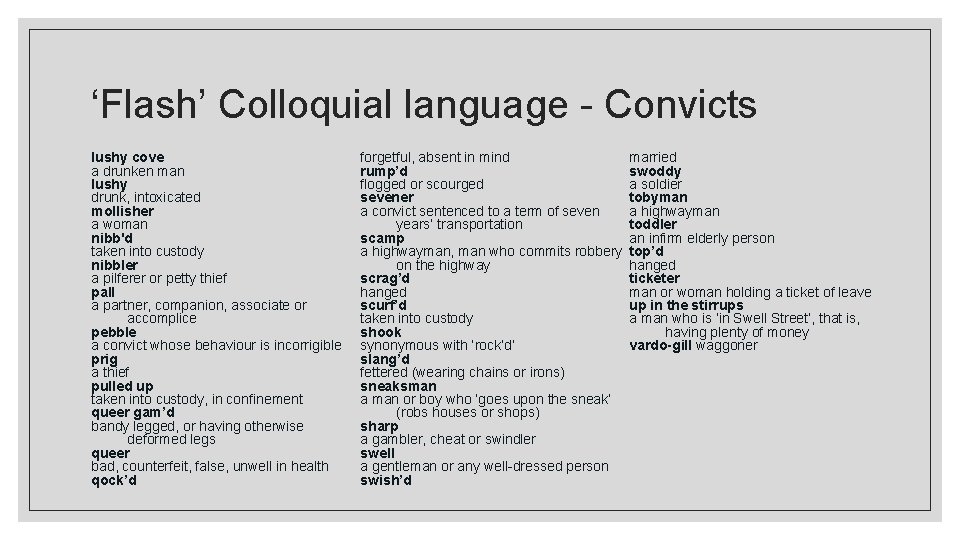

‘Flash’ Colloquial language – Convicts bad a convict who cooperates with police and officials bellowser a man transported for the term of his natural life bit-faker a coiner, maker of counterfeit money bolter one who runs away or leaves a place suddenly boned taken into custody breech’d flush with money, ‘in town’ brisket-beater a Roman Catholic bug nickname given to Englishmen by the Irish bush’d poor, without money buz cove a pickpocket buz covess a female pickpocket charley a watchman cly-faker a pickpocket cockatoo a convict who served a sentence on Cockatoo Island cracksman a house-breaker crap’d hanged croppy a convict (originally an Irish convict) darbie'd fettered (wearing chains or irons) done convicted file a person who has had a long course of experience in the arts of fraud floor'd so drunk as to be incapable of standing fly vigilant, cunning, not easily duped galloot a soldier grab'd taken, apprehended horney a constable in town flush with money, ‘breech’d’ kid a child, but particularly a boy who begins thieving at an early age kinchen a young lad knuckler a pickpocket lifer someone transported with a life sentence lag a convict under sentence of transportation lagger a sailor ◦ 'Indians’ - reflects a colonial name for Indigenous people that was commonly used to refer to the Aboriginal peoples of the Port Jackson and Botany Bay regions in the late 18 th century.

‘Flash’ Colloquial language - Convicts lushy cove a drunken man lushy drunk, intoxicated mollisher a woman nibb'd taken into custody nibbler a pilferer or petty thief pall a partner, companion, associate or accomplice pebble a convict whose behaviour is incorrigible prig a thief pulled up taken into custody, in confinement queer gam’d bandy legged, or having otherwise deformed legs queer bad, counterfeit, false, unwell in health qock’d forgetful, absent in mind rump’d flogged or scourged sevener a convict sentenced to a term of seven years’ transportation scamp a highwayman, man who commits robbery on the highway scrag’d hanged scurf’d taken into custody shook synonymous with ‘rock’d’ slang’d fettered (wearing chains or irons) sneaksman a man or boy who ‘goes upon the sneak’ (robs houses or shops) sharp a gambler, cheat or swindler swell a gentleman or any well-dressed person swish’d married swoddy a soldier tobyman a highwayman toddler an infirm elderly person top’d hanged ticketer man or woman holding a ticket of leave up in the stirrups a man who is ‘in Swell Street’, that is, having plenty of money vardo-gill waggoner

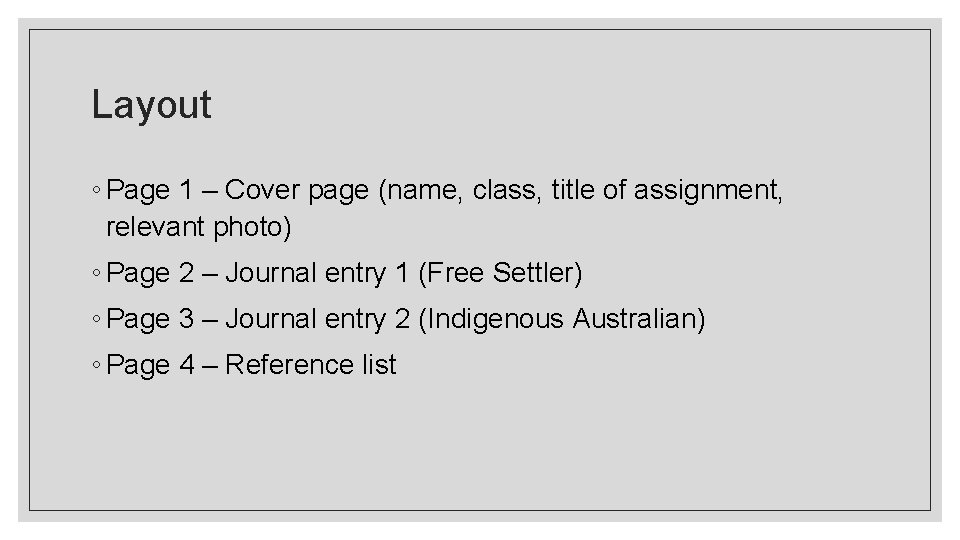

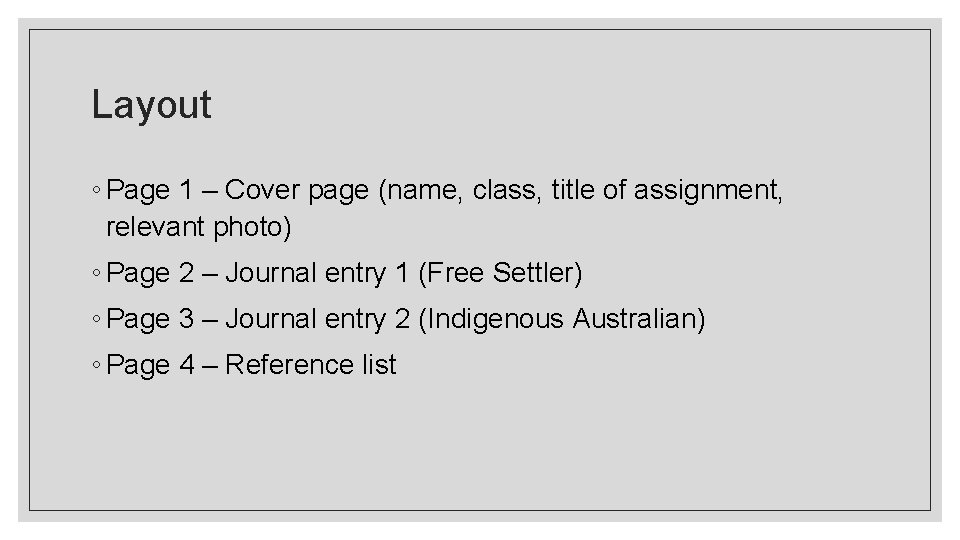

Layout ◦ Page 1 – Cover page (name, class, title of assignment, relevant photo) ◦ Page 2 – Journal entry 1 (Free Settler) ◦ Page 3 – Journal entry 2 (Indigenous Australian) ◦ Page 4 – Reference list

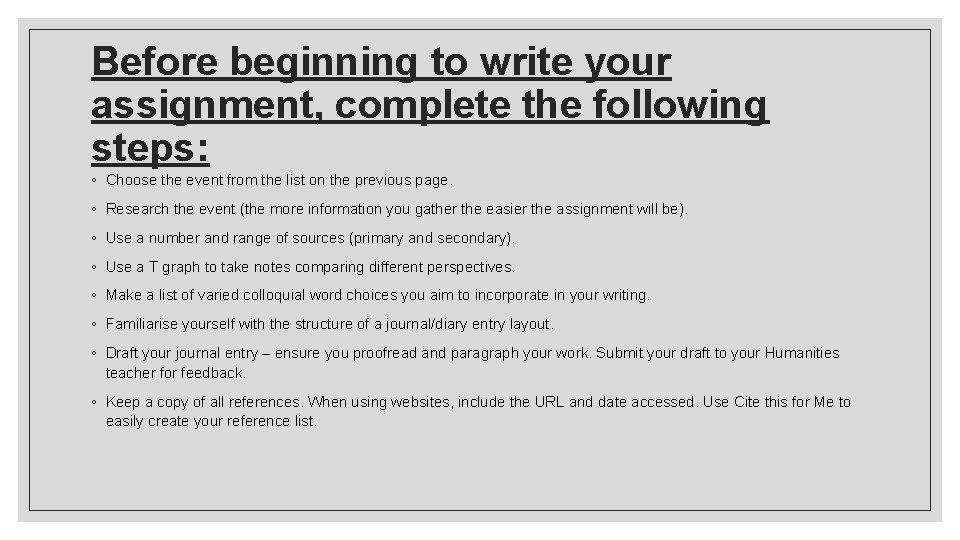

Before beginning to write your assignment, complete the following steps: ◦ Choose the event from the list on the previous page. ◦ Research the event (the more information you gather the easier the assignment will be). ◦ Use a number and range of sources (primary and secondary). ◦ Use a T graph to take notes comparing different perspectives. ◦ Make a list of varied colloquial word choices you aim to incorporate in your writing. ◦ Familiarise yourself with the structure of a journal/diary entry layout. ◦ Draft your journal entry – ensure you proofread and paragraph your work. Submit your draft to your Humanities teacher for feedback. ◦ Keep a copy of all references. When using websites, include the URL and date accessed. Use Cite this for Me to easily create your reference list.

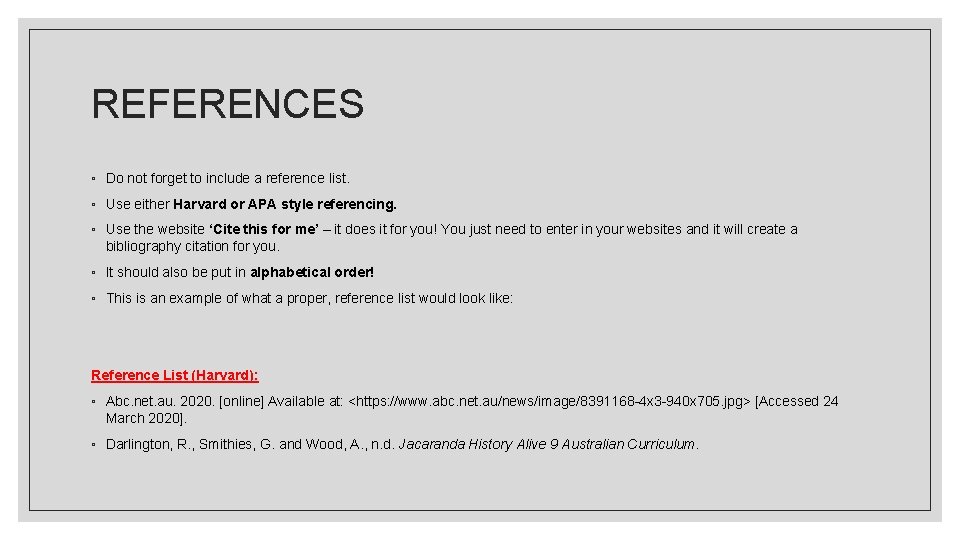

REFERENCES ◦ Do not forget to include a reference list. ◦ Use either Harvard or APA style referencing. ◦ Use the website ‘Cite this for me’ – it does it for you! You just need to enter in your websites and it will create a bibliography citation for you. ◦ It should also be put in alphabetical order! ◦ This is an example of what a proper, reference list would look like: Reference List (Harvard): ◦ Abc. net. au. 2020. [online] Available at: <https: //www. abc. net. au/news/image/8391168 -4 x 3 -940 x 705. jpg> [Accessed 24 March 2020]. ◦ Darlington, R. , Smithies, G. and Wood, A. , n. d. Jacaranda History Alive 9 Australian Curriculum.

EXAMPLES Use these as a guide only.

MYALL CREEK MASSACRE

Indigenous Perspective: Davy (An Aboriginal man who was an employee of Henry Danger (the owner of Myall Creek Station) 27 th of November, 1938 Today was the day of the second trial. It was finally decided that 7 of the 11 stockmen were going to be hung the following month. I was disgusted by the behavior of these men. They deserve something far worse than death. Shouldn’t they be beheaded, slashed and burnt like those poor Wirrayaraay people? They shouldn’t get the right to invade our traditional land then kill us original owners just because we’re in their way of establishing a settlement. Does it give them gratitude when they kill us Aboriginals? The day of the massacre I was with my brother Billy along with George Anderson and Charles Kilmeister who were both convicts. The Wirrayaraay tribe had come to the Myall Creek station a few days ago after being invited by Charles Kilmeister. Near the station huts, around 35 of them were camping. A few of the young men were at a nearby station cutting bark. Thomas Foster and William Mace from a nearby station came to borrow them this evening. The other Wirrayaraay people were left in the supervision of Kilmeister and Anderson. Soon, a group of white stockmen rid into the station. The Wirrayaraay people suddenly got up and ran into Anderson and Kilmeister’s hut of fear. Charles Kilmeister had a small chat with the stockmen before leaving to get his horse. The Wirrayaraay people quivered in fear, the women trying to assure their children. Anderson tried to argue but it didn’t work. 25 of the Wirrayaraay were then tied up at their necks. Billy and I spotted Anderson grab a girl’s hand hide her from the stockmen. I couldn’t let all these innocent people die, it was too cruel. I politely asked the stockmen if they would spare one of the Wirrayaraay for me. Anderson did too. The stockmen agreed, releasing two of the woman but then they ventured off to a nearby gully. The Aboriginals were begging for help, but there was nothing we could do. I watched as the sun set, wondering how people could possibly be so cruel. And how helpless I was. Soon after, I heard 2 gunshots. I waited an hour or two before running to the gully. I had seen the Wirrayaraay lying dead on the ground, with no head on their shoulders. I don’t know what happened to those men cutting bark but I do know that these stockmen completely deserved their punishment. I don’t understand why these white settlers think it’s okay to massacre Aboriginal and Indigenous people. (430 WORDS)

White settler Perspective: George Anderson 9 th June, 1838 We were resting up during the heat of the day when we heard horses to the south - galloping towards the station at full speed. Suddenly the Wirrayaraay tribe people camped at our station came running in, begging us to protect them. Three of the 11 armed stockmen who were now waiting outside called for convict stockman Charles Kilmeister and me to come out and speak with them. Once outside we recognised some of them, including John Fleming, who is the overseer at Mungie Bundie station, George Russell, George Palliser and many others who were unwelcome. They demanded that we hand over the Aborigines seeking refuge at our station. When I asked them what they were going to do, Fleming said that they were going to “take them over the back of the range to frighten them”. After pushing past us, the men rounded up the Aborigines with a long rope which they tied around their wrists, then to each other. They led them away while another man kept watch with his pistol drawn. The Aborigines still inside called for my help but there was nothing I could have done, we were hopelessly outnumbered. The stockmen led them off, leaving only dust in their wake. Kilmeister then grabbed his pistol, mounted up a horse and followed the stockmen. Fifteen minutes after Kilmeister had left, two gunshots went off in rapid succession and soon smoke started to weave its way through the treetops. After the shots went off, one of the Aboriginal cattle drovers, Davy, left to follow the stockmen and see what had happened. After a few tense minutes he came back and told me what he had seen. He told us how he had seen Kilmeister helping the stockmen, and how he had seen all of the innocent Aboriginals lying in pools of their own blood. Some had been decapitated, some shot and one had even been killed by being thrown into the flames. A few Wirrayaraay people came out of the bush once the stockmen had gone and in fear we locked ourselves in the shack, in case the stockmen came back. After some time there were knocks on the door and the rest of the Wirrayaraay people who had been working on another station arrived back. We begged them to leave and told them to take the few other Aboriginal people left and make haste to Andrew Eaton at Macintyre’s Run, 40 miles east. It was a terrible day that I shall never forget and I am glad that most of those criminals hanged for their crimes.

THE BATTLE OF PINJARRA

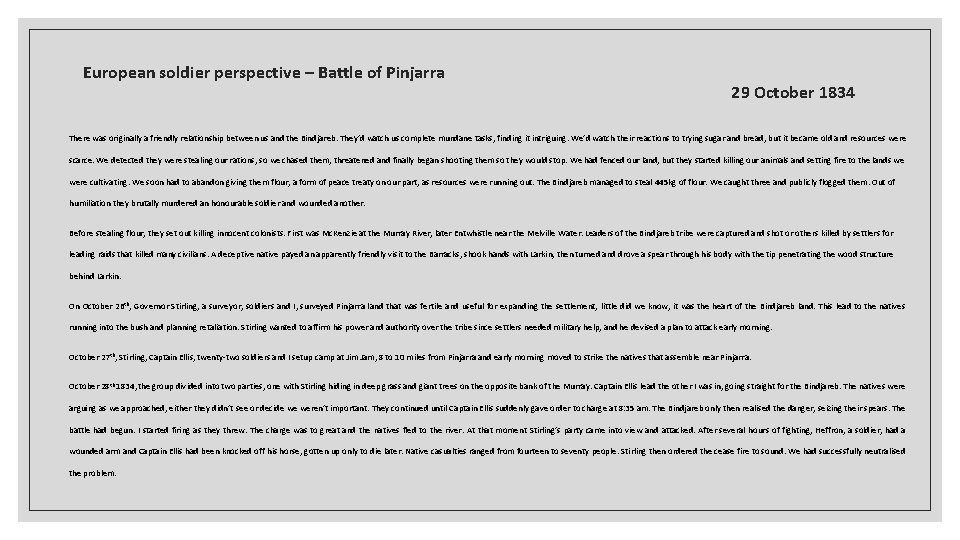

European soldier perspective – Battle of Pinjarra 29 October 1834 There was originally a friendly relationship between us and the Bindjareb. They’d watch us complete mundane tasks, finding it intriguing. We’d watch their reactions to trying sugar and bread, but it became old and resources were scarce. We detected they were stealing our rations, so we chased them, threatened and finally began shooting them so they would stop. We had fenced our land, but they started killing our animals and setting fire to the lands we were cultivating. We soon had to abandon giving them flour, a form of peace treaty on our part, as resources were running out. The Bindjareb managed to steal 445 kg of flour. We caught three and publicly flogged them. Out of humiliation they brutally murdered an honourable soldier and wounded another. Before stealing flour, they set out killing innocent colonists. First was Mc. Kenzie at the Murray River, later Entwhistle near the Melville Water. Leaders of the Bindjareb tribe were captured and shot or others killed by settlers for leading raids that killed many civilians. A deceptive native payed an apparently friendly visit to the Barracks, shook hands with Larkin, then turned and drove a spear through his body with the tip penetrating the wood structure behind Larkin. On October 26 th, Governor Stirling, a surveyor, soldiers and I, surveyed Pinjarra land that was fertile and useful for expanding the settlement, little did we know, it was the heart of the Bindjareb land. This lead to the natives running into the bush and planning retaliation. Stirling wanted to affirm his power and authority over the tribe since settlers needed military help, and he devised a plan to attack early morning. October 27 th, Stirling, Captain Ellis, twenty-two soldiers and I setup camp at Jim Jam, 8 to 10 miles from Pinjarra and early morning moved to strike the natives that assemble near Pinjarra. October 28 th 1834, the group divided into two parties, one with Stirling hiding in deep grass and giant trees on the opposite bank of the Murray. Captain Ellis lead the other I was in, going straight for the Bindjareb. The natives were arguing as we approached, either they didn’t see or decide we weren’t important. They continued until Captain Ellis suddenly gave order to charge at 8: 35 am. The Bindjareb only then realised the danger, seizing their spears. The battle had begun. I started firing as they threw. The charge was to great and the natives fled to the river. At that moment Stirling’s party came into view and attacked. After several hours of fighting, Heffron, a soldier, had a wounded arm and Captain Ellis had been knocked off his horse, gotten up only to die later. Native casualties ranged from fourteen to seventy people. Stirling then ordered the cease fire to sound. We had successfully neutralised the problem.

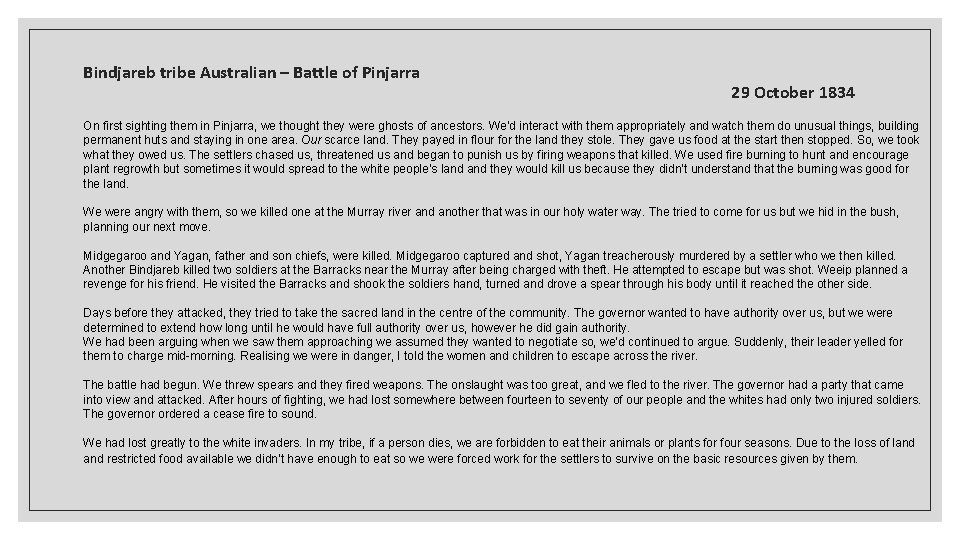

Bindjareb tribe Australian – Battle of Pinjarra 29 October 1834 On first sighting them in Pinjarra, we thought they were ghosts of ancestors. We’d interact with them appropriately and watch them do unusual things, building permanent huts and staying in one area. Our scarce land. They payed in flour for the land they stole. They gave us food at the start then stopped. So, we took what they owed us. The settlers chased us, threatened us and began to punish us by firing weapons that killed. We used fire burning to hunt and encourage plant regrowth but sometimes it would spread to the white people’s land they would kill us because they didn’t understand that the burning was good for the land. We were angry with them, so we killed one at the Murray river and another that was in our holy water way. The tried to come for us but we hid in the bush, planning our next move. Midgegaroo and Yagan, father and son chiefs, were killed. Midgegaroo captured and shot, Yagan treacherously murdered by a settler who we then killed. Another Bindjareb killed two soldiers at the Barracks near the Murray after being charged with theft. He attempted to escape but was shot. Weeip planned a revenge for his friend. He visited the Barracks and shook the soldiers hand, turned and drove a spear through his body until it reached the other side. Days before they attacked, they tried to take the sacred land in the centre of the community. The governor wanted to have authority over us, but we were determined to extend how long until he would have full authority over us, however he did gain authority. We had been arguing when we saw them approaching we assumed they wanted to negotiate so, we’d continued to argue. Suddenly, their leader yelled for them to charge mid-morning. Realising we were in danger, I told the women and children to escape across the river. The battle had begun. We threw spears and they fired weapons. The onslaught was too great, and we fled to the river. The governor had a party that came into view and attacked. After hours of fighting, we had lost somewhere between fourteen to seventy of our people and the whites had only two injured soldiers. The governor ordered a cease fire to sound. We had lost greatly to the white invaders. In my tribe, if a person dies, we are forbidden to eat their animals or plants for four seasons. Due to the loss of land restricted food available we didn’t have enough to eat so we were forced work for the settlers to survive on the basic resources given by them.