XML XPath and XQuery Zachary G Ives University

- Slides: 47

XML, XPath, and XQuery Zachary G. Ives University of Pennsylvania CIS 550 – Database & Information Systems October 18, 2005 Some slide content courtesy of Susan Davidson & Raghu Ramakrishnan

Administrivia § Upcoming: recitation section on the RSS feeder § Project plans due 11/1 § For projects other than RSS feeder: description of project goals § In all cases: Describe how you will be dividing up the work § List of project milestones (remember to leave time for integration!) § Homework 4 (XML) will be due 11/3 2

Why XML? XML is the confluence of several factors: § § § The Web needed a more declarative format for data Documents needed a mechanism for extended tags Database people needed a more flexible interchange format “Lingua franca” of data It’s parsable even if we don’t know what it means! Original expectation: § The whole web would go to XML instead of HTML Today’s reality: § Not so… But XML is used all over “under the covers” 3

Why DB People Like XML Can get data from all sorts of sources § Allows us to touch data we don’t own! § This was actually a huge change in the DB community Interesting relationships with DB techniques § Useful to do relational-style operations § Leverages ideas from object-oriented, semistructured data Blends schema and data into one format § Unlike relational model, where we need schema first § … But too little schema can be a drawback, too! 4

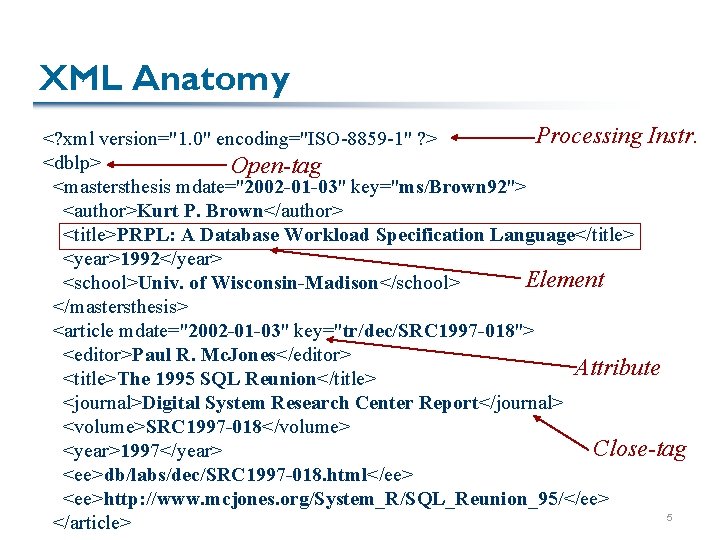

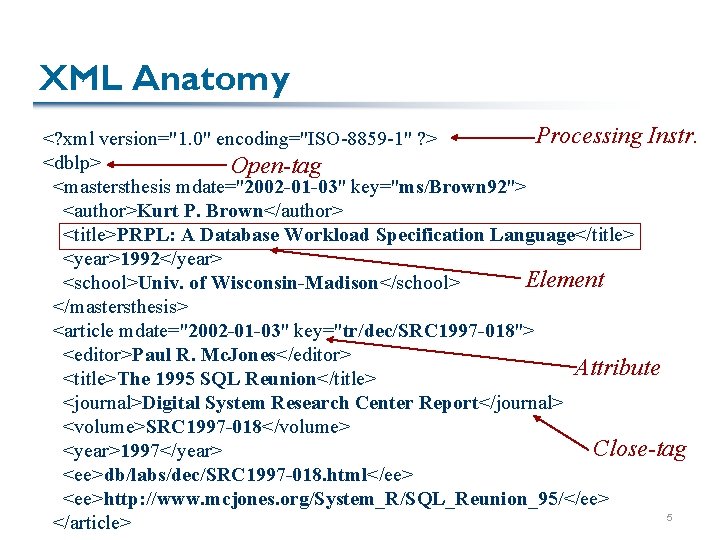

XML Anatomy Processing Instr. <? xml version="1. 0" encoding="ISO-8859 -1" ? > <dblp> Open-tag <mastersthesis mdate="2002 -01 -03" key="ms/Brown 92"> <author>Kurt P. Brown</author> <title>PRPL: A Database Workload Specification Language</title> <year>1992</year> Element <school>Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison</school> </mastersthesis> <article mdate="2002 -01 -03" key="tr/dec/SRC 1997 -018"> <editor>Paul R. Mc. Jones</editor> Attribute <title>The 1995 SQL Reunion</title> <journal>Digital System Research Center Report</journal> <volume>SRC 1997 -018</volume> Close-tag <year>1997</year> <ee>db/labs/dec/SRC 1997 -018. html</ee> <ee>http: //www. mcjones. org/System_R/SQL_Reunion_95/</ee> 5 </article>

Well-Formed XML A legal XML document – fully parsable by an XML parser § All open-tags have matching close-tags (unlike so many HTML documents!), or a special: <tag/> shortcut for empty tags (equivalent to <tag></tag> § Attributes (which are unordered, in contrast to elements) only appear once in an element § There’s a single root element § XML is case-sensitive 6

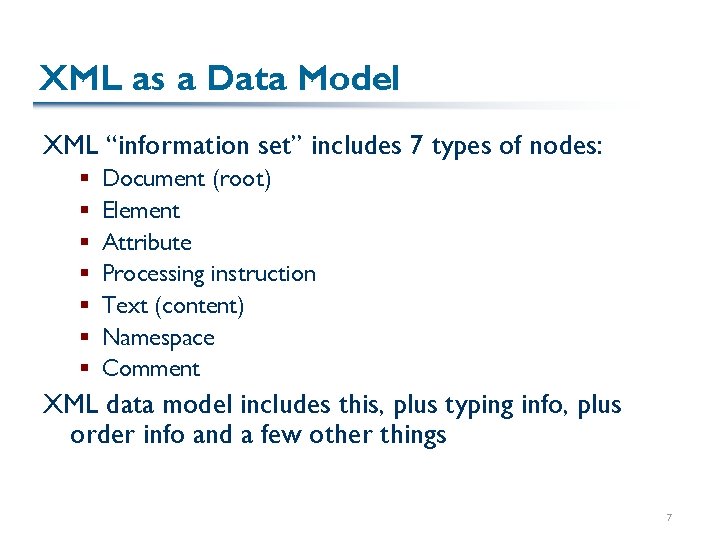

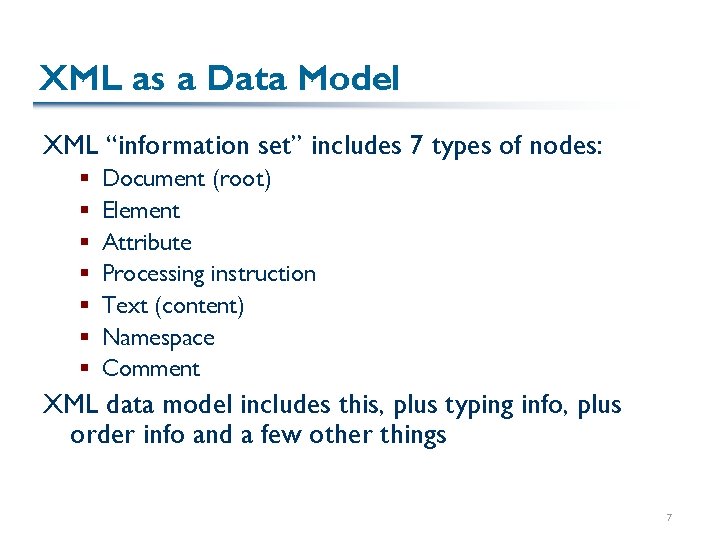

XML as a Data Model XML “information set” includes 7 types of nodes: § § § § Document (root) Element Attribute Processing instruction Text (content) Namespace Comment XML data model includes this, plus typing info, plus order info and a few other things 7

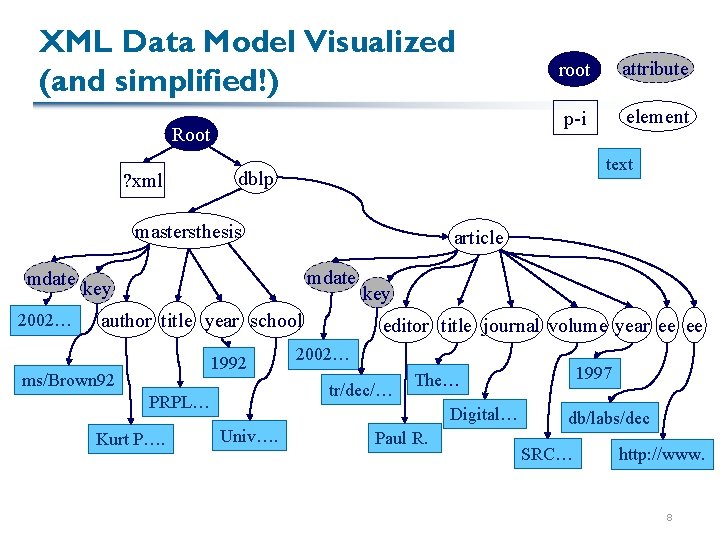

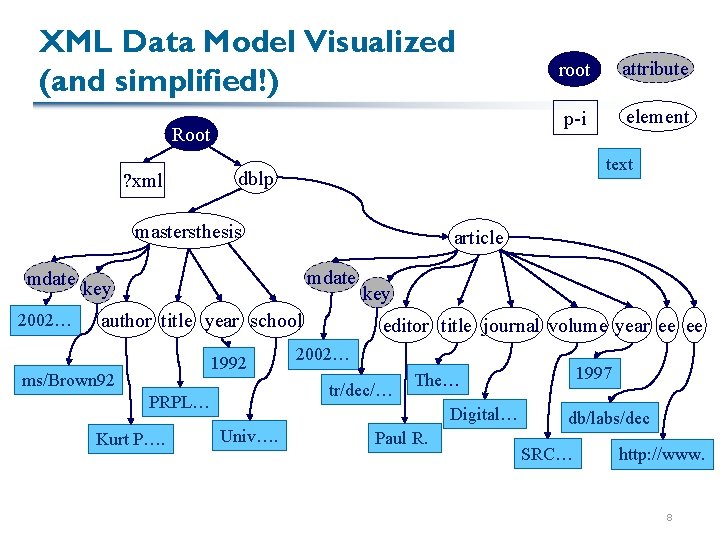

XML Data Model Visualized (and simplified!) Root ? xml 2002… element article mdate author title year school 1992 key editor title journal volume year ee ee 2002… tr/dec/… PRPL… Kurt P…. p-i dblp key ms/Brown 92 attribute text mastersthesis mdate root Digital… Univ…. 1997 The… Paul R. db/labs/dec SRC… http: //www. 8

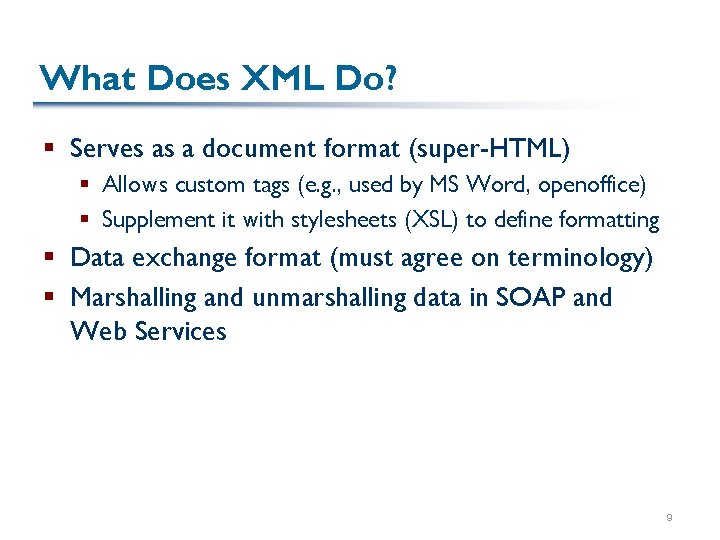

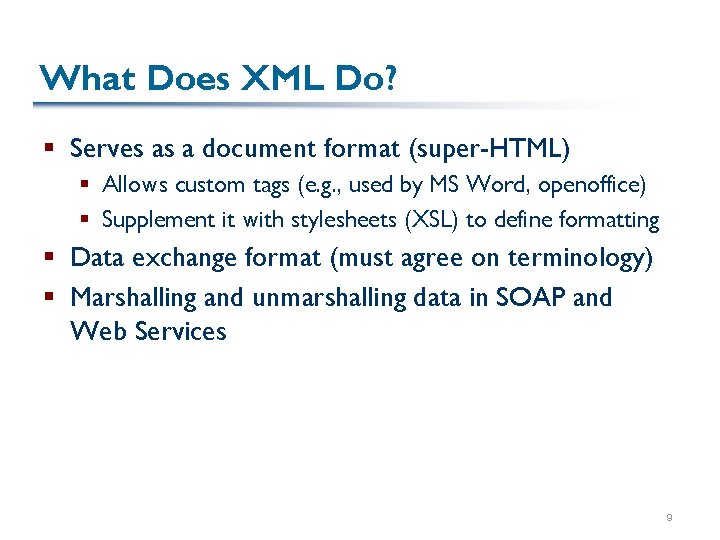

What Does XML Do? § Serves as a document format (super-HTML) § Allows custom tags (e. g. , used by MS Word, openoffice) § Supplement it with stylesheets (XSL) to define formatting § Data exchange format (must agree on terminology) § Marshalling and unmarshalling data in SOAP and Web Services 9

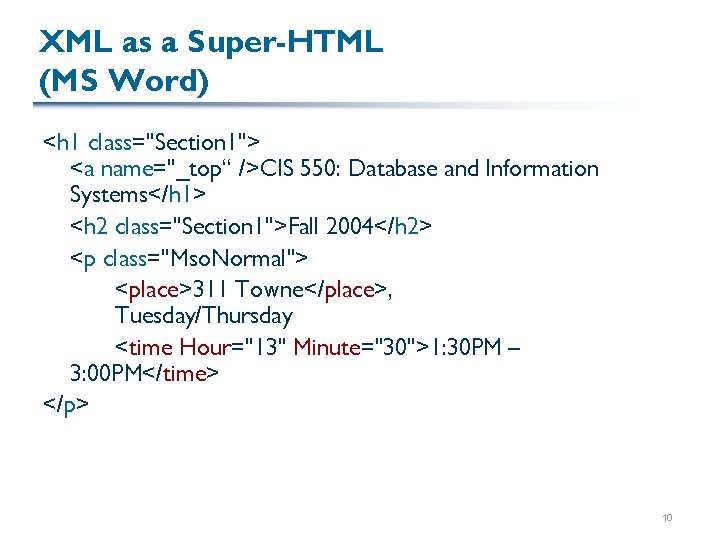

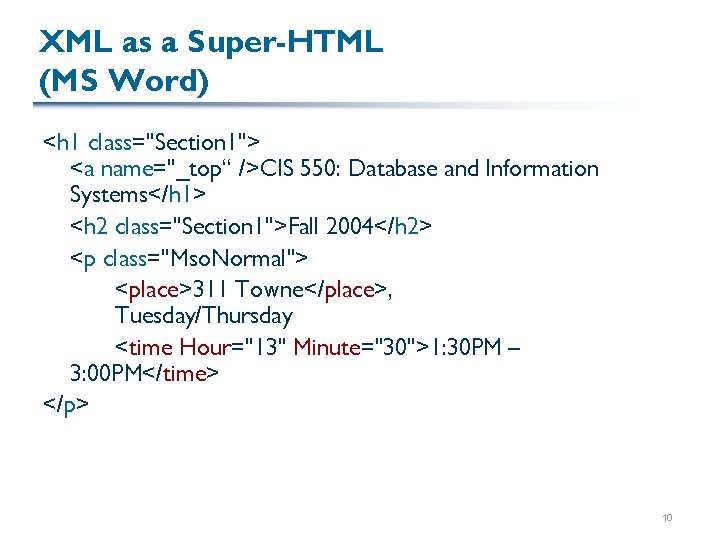

XML as a Super-HTML (MS Word) <h 1 class="Section 1"> <a name="_top“ />CIS 550: Database and Information Systems</h 1> <h 2 class="Section 1">Fall 2004</h 2> <p class="Mso. Normal"> <place>311 Towne</place>, Tuesday/Thursday <time Hour="13" Minute="30">1: 30 PM – 3: 00 PM</time> </p> 10

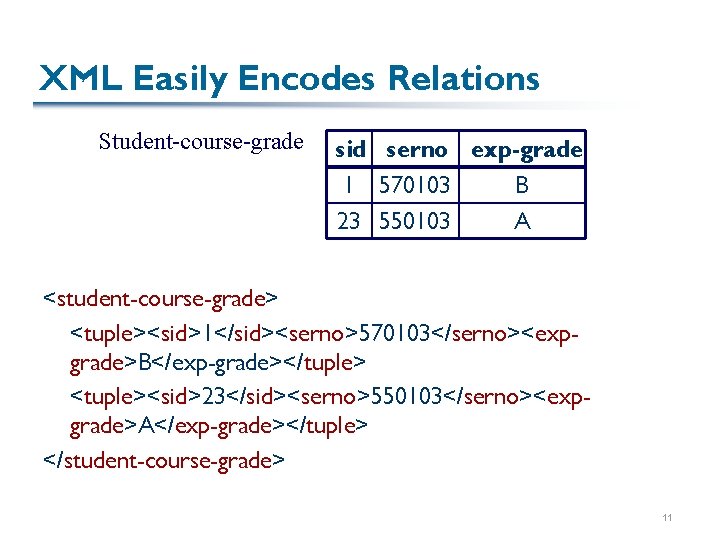

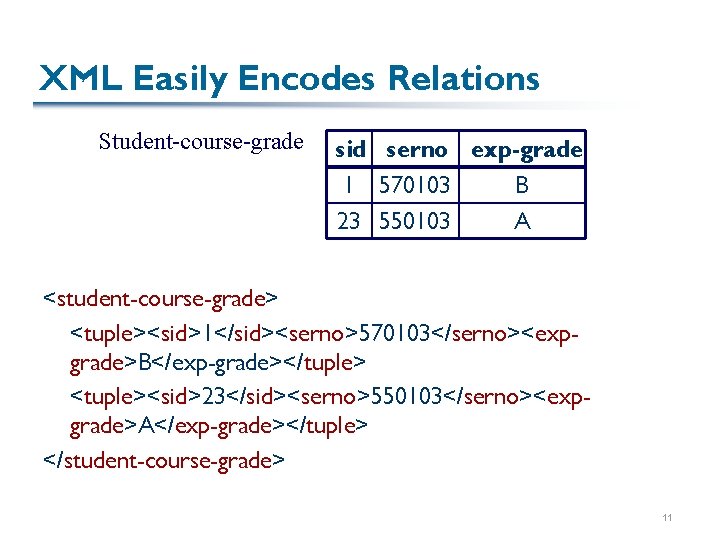

XML Easily Encodes Relations Student-course-grade sid serno exp-grade 1 570103 B 23 550103 A <student-course-grade> <tuple><sid>1</sid><serno>570103</serno><expgrade>B</exp-grade></tuple> <tuple><sid>23</sid><serno>550103</serno><expgrade>A</exp-grade></tuple> </student-course-grade> 11

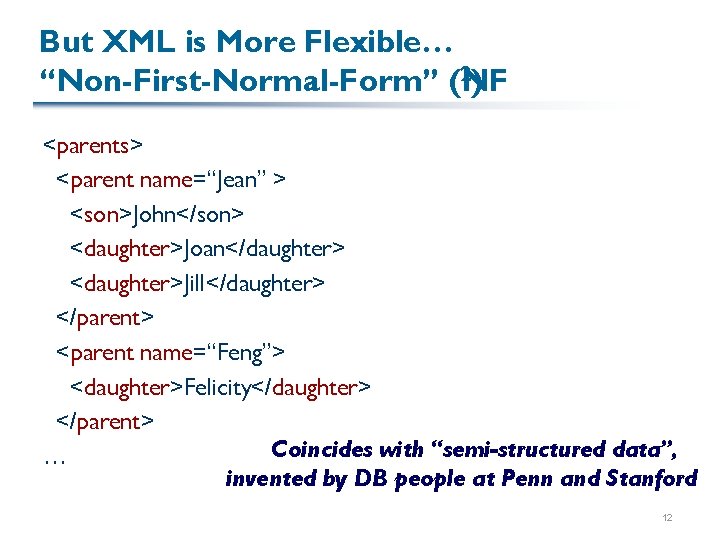

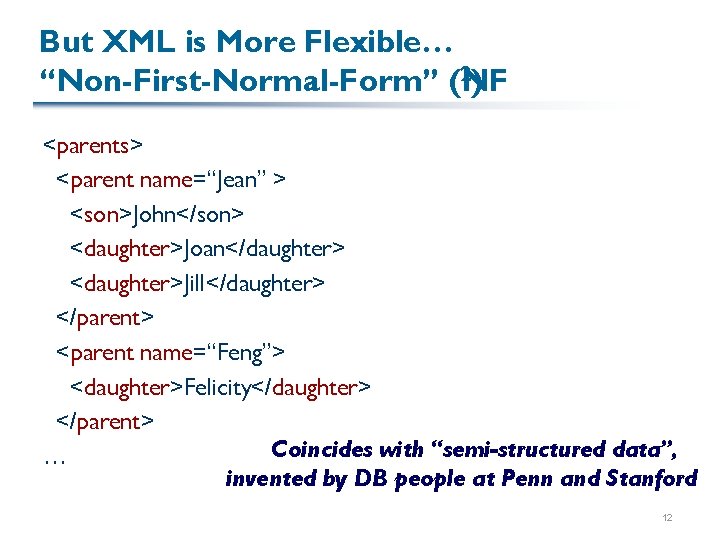

But XML is More Flexible… 2) “Non-First-Normal-Form” (NF <parents> <parent name=“Jean” > <son>John</son> <daughter>Joan</daughter> <daughter>Jill</daughter> </parent> <parent name=“Feng”> <daughter>Felicity</daughter> </parent> Coincides with “semi-structured data”, … invented by DB people at Penn and Stanford 12

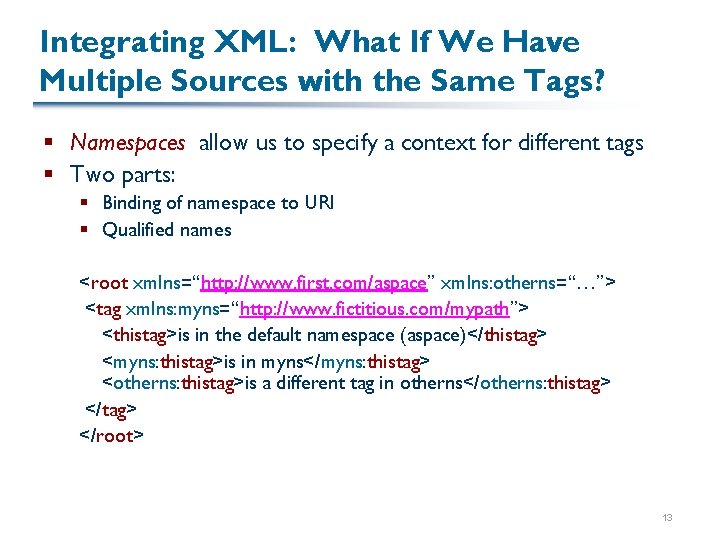

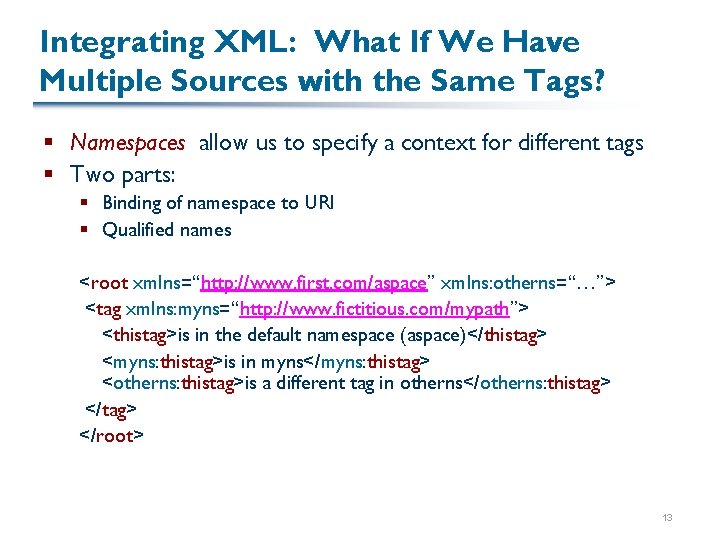

Integrating XML: What If We Have Multiple Sources with the Same Tags? § Namespaces allow us to specify a context for different tags § Two parts: § Binding of namespace to URI § Qualified names <root xmlns=“http: //www. first. com/aspace” xmlns: otherns=“…”> <tag xmlns: myns=“http: //www. fictitious. com/mypath”> <thistag>is in the default namespace (aspace)</thistag> <myns: thistag>is in myns</myns: thistag> <otherns: thistag>is a different tag in otherns</otherns: thistag> </root> 13

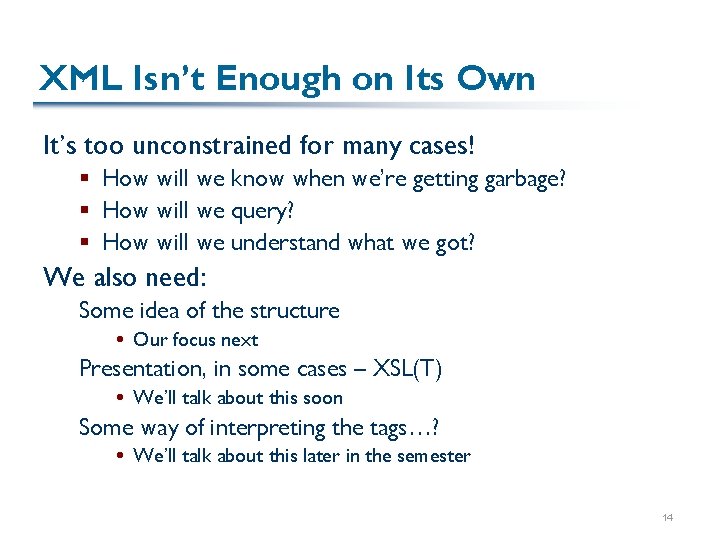

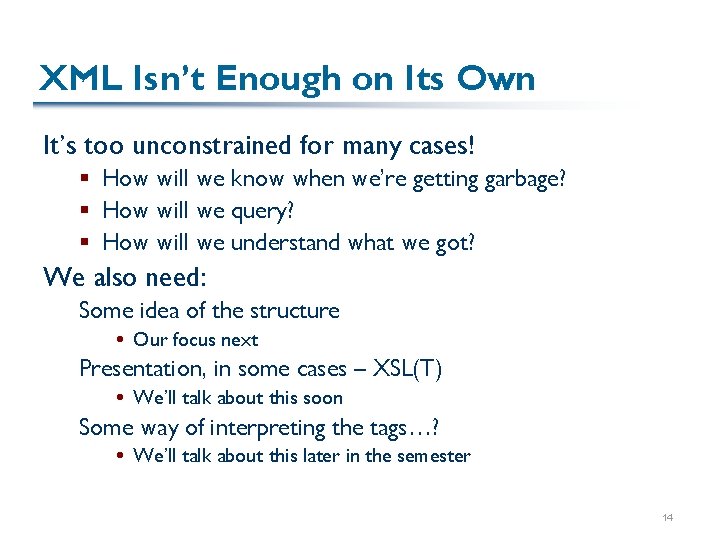

XML Isn’t Enough on Its Own It’s too unconstrained for many cases! § How will we know when we’re getting garbage? § How will we query? § How will we understand what we got? We also need: Some idea of the structure Our focus next Presentation, in some cases – XSL(T) We’ll talk about this soon Some way of interpreting the tags…? We’ll talk about this later in the semester 14

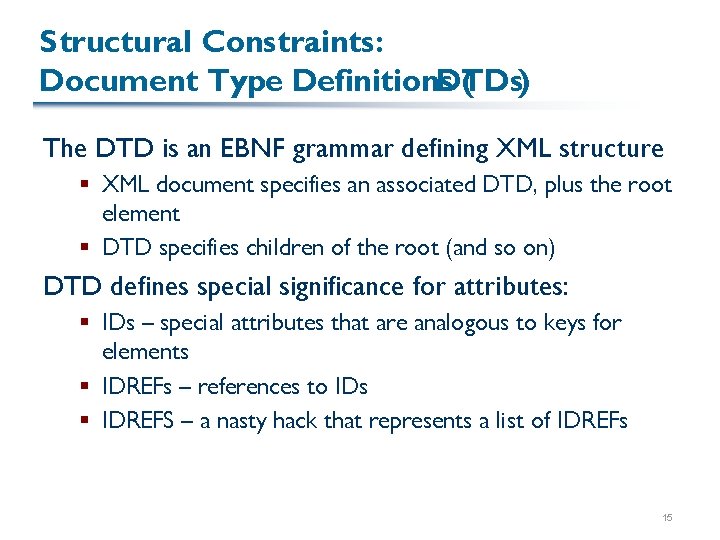

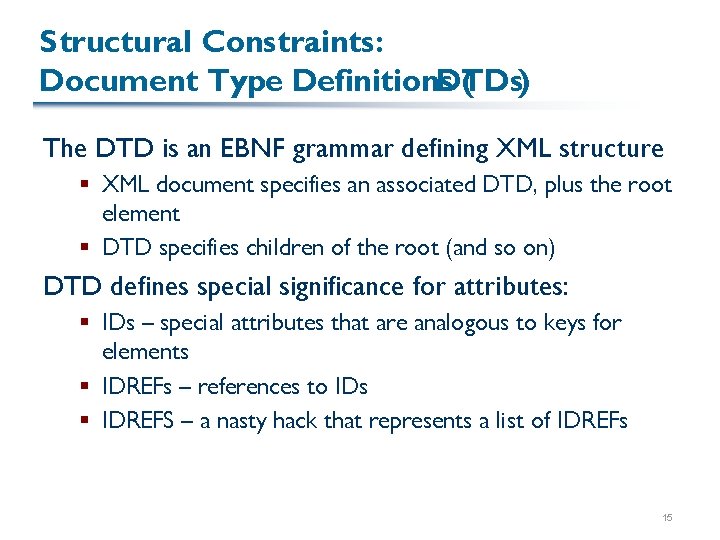

Structural Constraints: Document Type Definitions DTDs) ( The DTD is an EBNF grammar defining XML structure § XML document specifies an associated DTD, plus the root element § DTD specifies children of the root (and so on) DTD defines special significance for attributes: § IDs – special attributes that are analogous to keys for elements § IDREFs – references to IDs § IDREFS – a nasty hack that represents a list of IDREFs 15

An Example DTD: <!ELEMENT dblp((mastersthesis | article)*)> <!ELEMENT mastersthesis(author, title, year, school, committeemember*)> <!ATTLIST mastersthesis(mdate CDATA #REQUIRED key ID #REQUIRED advisor CDATA #IMPLIED> <!ELEMENT author(#PCDATA)> … Example use of DTD in XML file: <? xml version="1. 0" encoding="ISO-8859 -1" ? > <!DOCTYPEdblp SYSTEM my. dtd “ "> <dblp>… 16

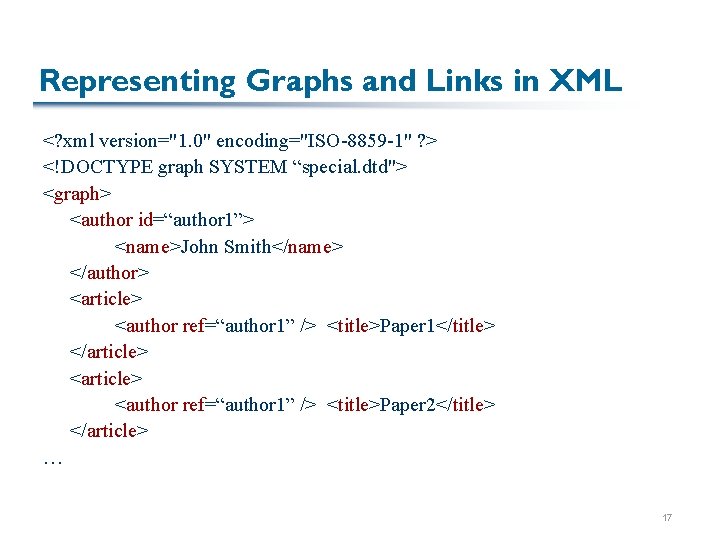

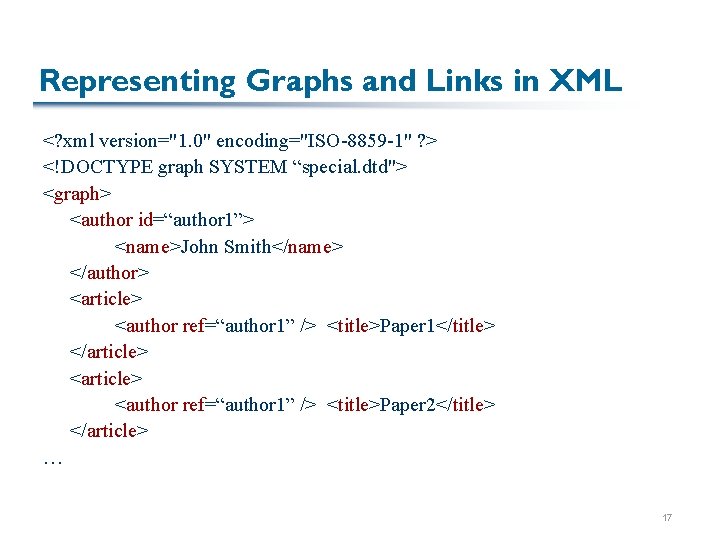

Representing Graphs and Links in XML <? xml version="1. 0" encoding="ISO-8859 -1" ? > <!DOCTYPE graph SYSTEM “special. dtd"> <graph> <author id=“author 1”> <name>John Smith</name> </author> <article> <author ref=“author 1” /> <title>Paper 1</title> </article> <author ref=“author 1” /> <title>Paper 2</title> </article> … 17

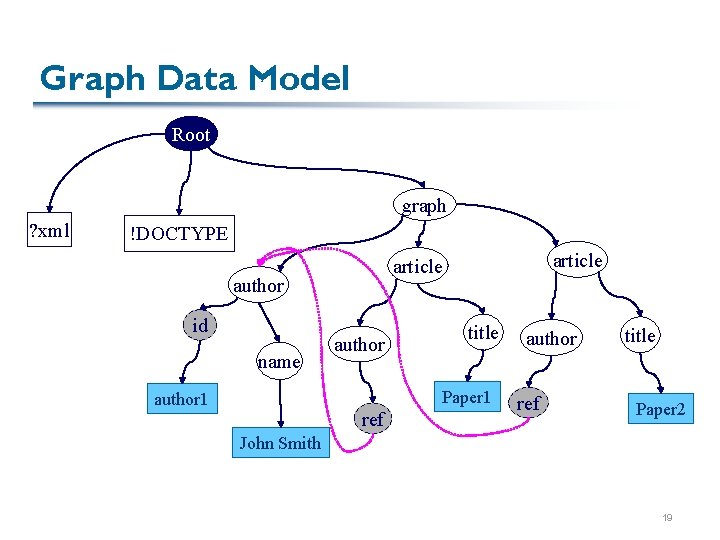

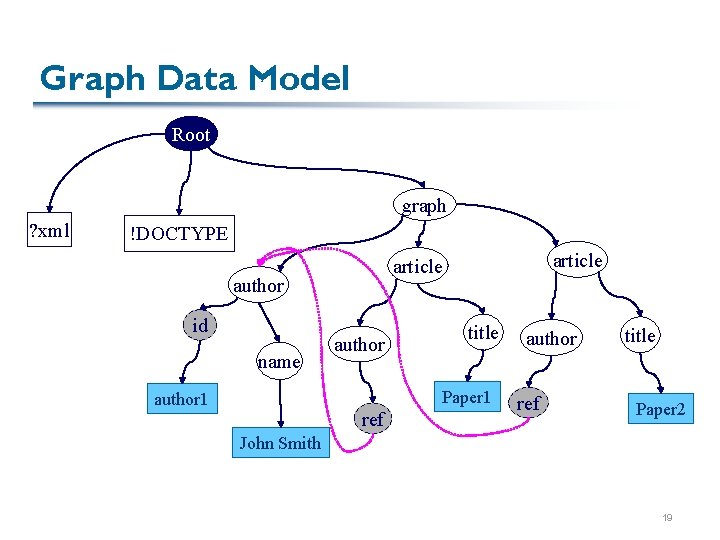

Graph Data Model Root graph ? xml !DOCTYPE author id name article author title Paper 1 author 1 ref author ref title Paper 2 John Smith author 1 18

Graph Data Model Root graph ? xml !DOCTYPE author id name article author title Paper 1 author 1 ref author ref title Paper 2 John Smith 19

DTDs Aren’t Expressive Enough DTDs capture grammatical structure, but have some drawbacks: § Not themselves in XML – inconvenient to build tools for them § Don’t capture database datatypes’ domains § IDs aren’t a good implementation of keys Why not? § No way of defining OO-like inheritance 20

XML Schema Aims to address the shortcomings of DTDs § XML syntax § Can define keys using XPaths § Type subclassing that’s more complex than in a programming language Programming languages don’t consider order of member variables! Subclassing “by extension” and “by restriction” § … And, of course, domains and built-in datatypes 21

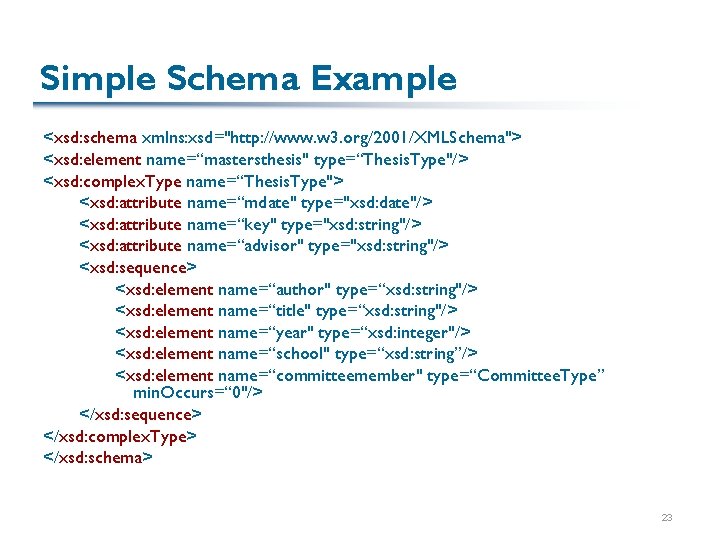

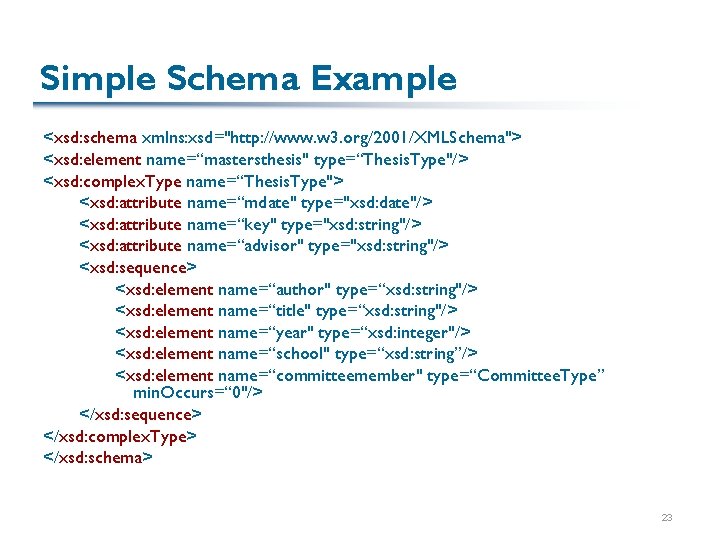

Basics of XML Schema Need to use the XML Schema namespace (generally named xsd) § simple. Types are a way of restricting domains on scalars § Can define a simple. Type based on integer, with values within a particular range § complex. Types are a way of defining element/attribute structures § Basically equivalent to !ELEMENT, but more powerful § Specify sequence, choice between child elements § Specify min. Occurs and max. Occurs (default 1) § Must associate an element/attribute with a simple. Type, or an element with a complex. Type 22

Simple Schema Example <xsd: schema xmlns: xsd="http: //www. w 3. org/2001/XMLSchema"> <xsd: element name=“mastersthesis" type=“Thesis. Type"/> <xsd: complex. Type name=“Thesis. Type"> <xsd: attribute name=“mdate" type="xsd: date"/> <xsd: attribute name=“key" type="xsd: string"/> <xsd: attribute name=“advisor" type="xsd: string"/> <xsd: sequence> <xsd: element name=“author" type=“xsd: string"/> <xsd: element name=“title" type=“xsd: string"/> <xsd: element name=“year" type=“xsd: integer"/> <xsd: element name=“school" type=“xsd: string”/> <xsd: element name=“committeemember" type=“Committee. Type” min. Occurs=“ 0"/> </xsd: sequence> </xsd: complex. Type> </xsd: schema> 23

Designing an XML Schema/DTD Not as formalized as relational data design § We can still use ER diagrams to break into entity, relationship sets § ER diagrams have extensions for “aggregation” – treating smaller diagrams as entities – and for composite attributes § Note that often we already have our data in relations and need to design the XML schema to export them! Generally orient the XML tree around the “central” objects Big decision: element vs. attribute § Element if it has its own properties, or if you *might* have more than one of them § Attribute if it is a single property – or perhaps not! 24

Recap: XML as a Data Model XML is a non-first-normal-form (NF 2) representation § Can represent documents, data § Standard data exchange format § Several competing schema formats – esp. , DTD and XML Schema – provide typing information 25

Querying XML How do you query a directed graph? a tree? The standard approach used by many XML, semistructured-data, and object query languages: § Define some sort of a template describing traversals from the root of the directed graph § In XML, the basis of this template is called an XPath 26

XPaths In its simplest form, an XPath is like a path in a file system: /mypath/subpath/*/morepath § The XPath returns a node set representing the XML nodes (and their subtrees) at the end of the path § XPaths can have node tests at the end, returning only particular node types, e. g. , text(), processing-instruction(), comment(), element(), attribute() § XPath is fundamentally an ordered language: it can query in order-aware fashion, and it returns nodes in order 27

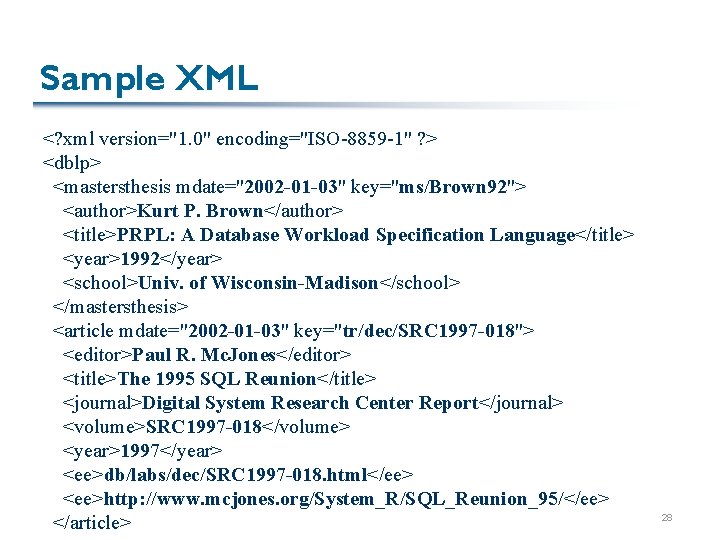

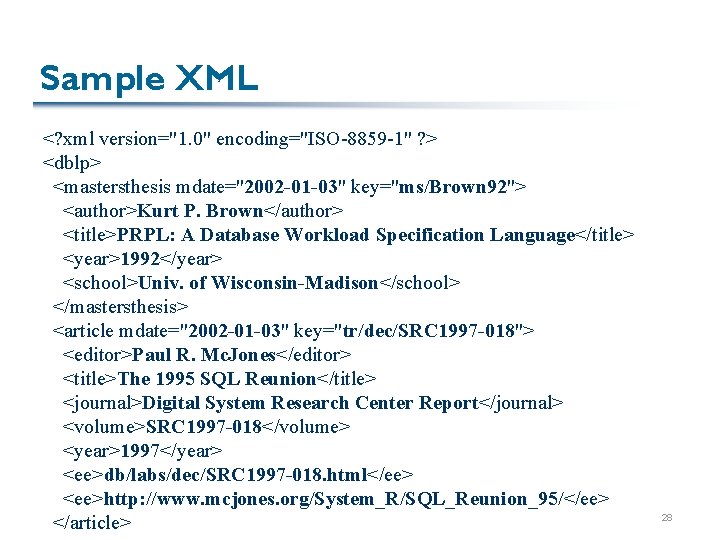

Sample XML <? xml version="1. 0" encoding="ISO-8859 -1" ? > <dblp> <mastersthesis mdate="2002 -01 -03" key="ms/Brown 92"> <author>Kurt P. Brown</author> <title>PRPL: A Database Workload Specification Language</title> <year>1992</year> <school>Univ. of Wisconsin-Madison</school> </mastersthesis> <article mdate="2002 -01 -03" key="tr/dec/SRC 1997 -018"> <editor>Paul R. Mc. Jones</editor> <title>The 1995 SQL Reunion</title> <journal>Digital System Research Center Report</journal> <volume>SRC 1997 -018</volume> <year>1997</year> <ee>db/labs/dec/SRC 1997 -018. html</ee> <ee>http: //www. mcjones. org/System_R/SQL_Reunion_95/</ee> </article> 28

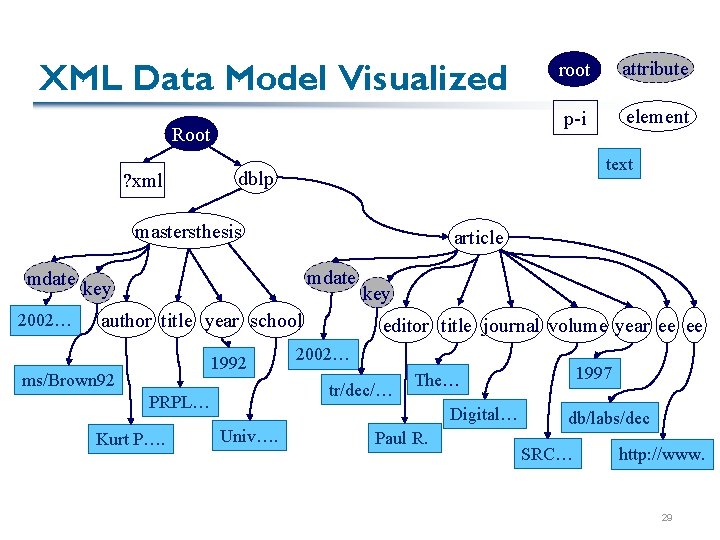

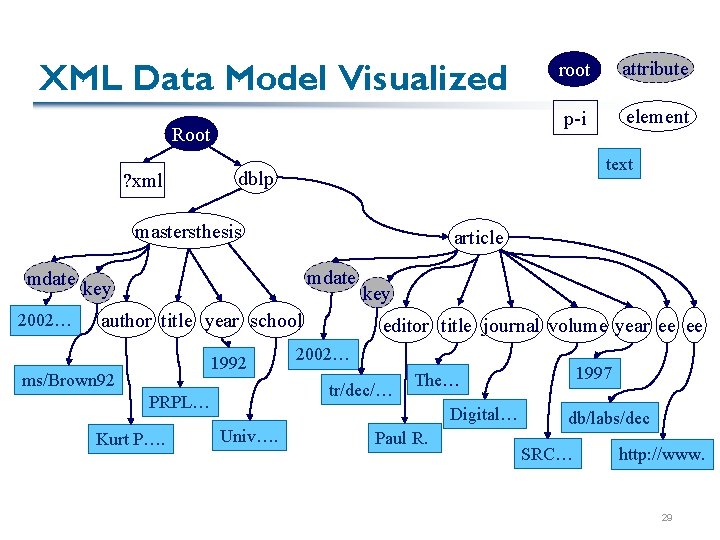

XML Data Model Visualized Root ? xml 2002… element article mdate author title year school 1992 key editor title journal volume year ee ee 2002… tr/dec/… PRPL… Kurt P…. p-i dblp key ms/Brown 92 attribute text mastersthesis mdate root Digital… Univ…. 1997 The… Paul R. db/labs/dec SRC… http: //www. 29

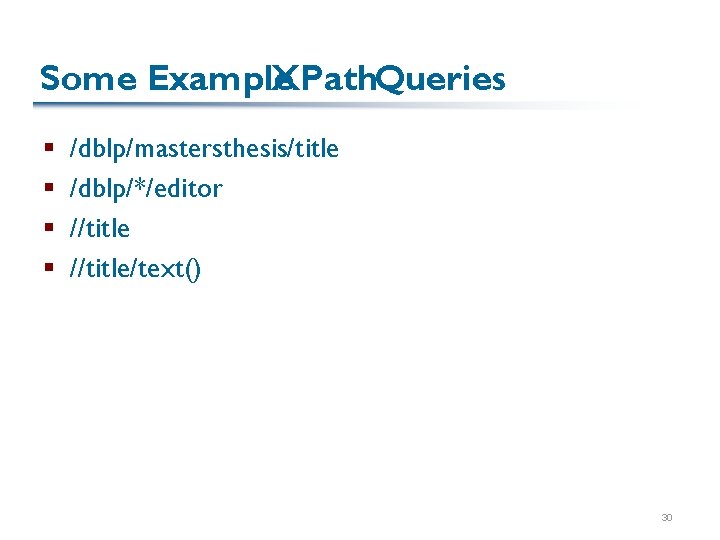

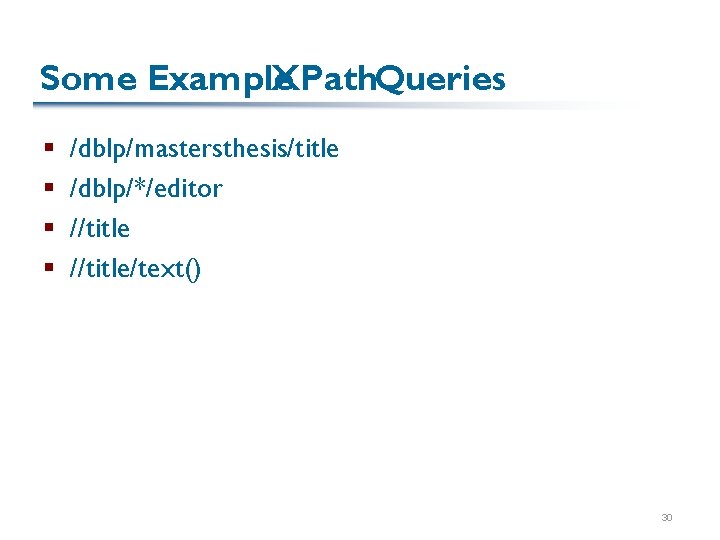

Some Example XPath. Queries § § /dblp/mastersthesis/title /dblp/*/editor //title/text() 30

Context Nodes and Relative Paths XPath has a notion of a context node: it’s analogous to a current directory § “. ” represents this context node § “. . ” represents the parent node § We can express relative paths: subpath/sub-subpath/. . gets us back to the context node Ø By default, the document root is the context node 31

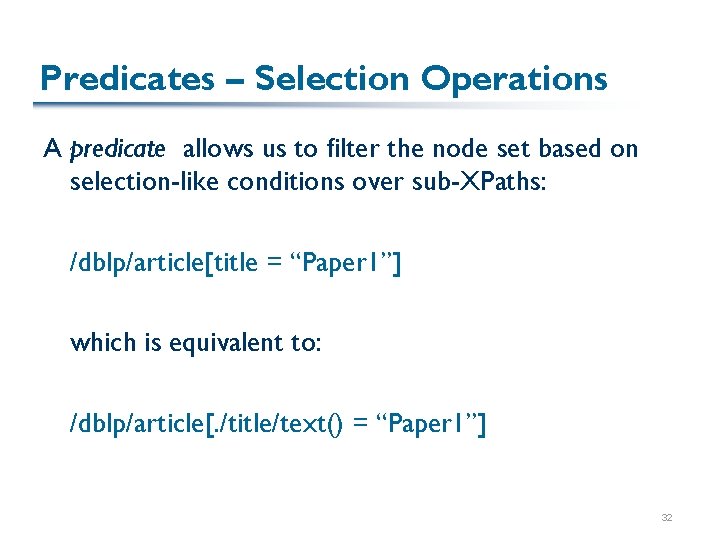

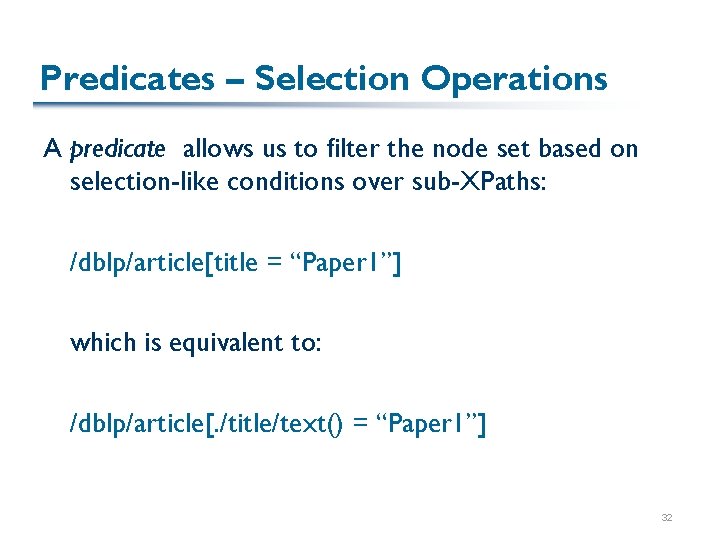

Predicates – Selection Operations A predicate allows us to filter the node set based on selection-like conditions over sub-XPaths: /dblp/article[title = “Paper 1”] which is equivalent to: /dblp/article[. /title/text() = “Paper 1”] 32

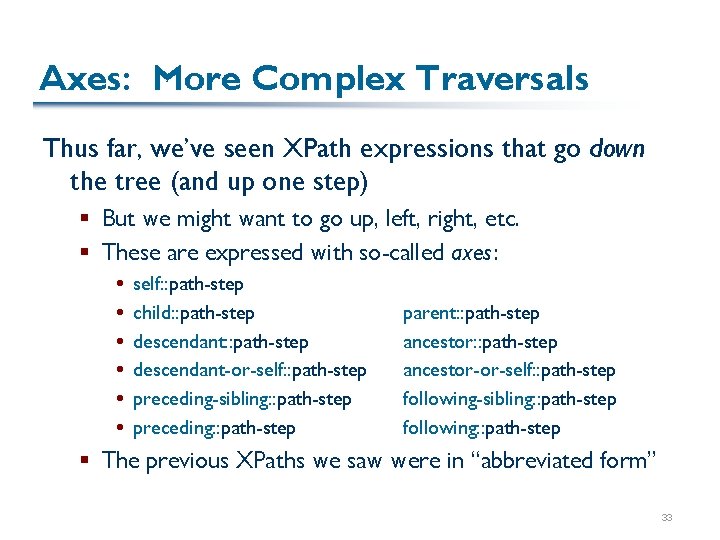

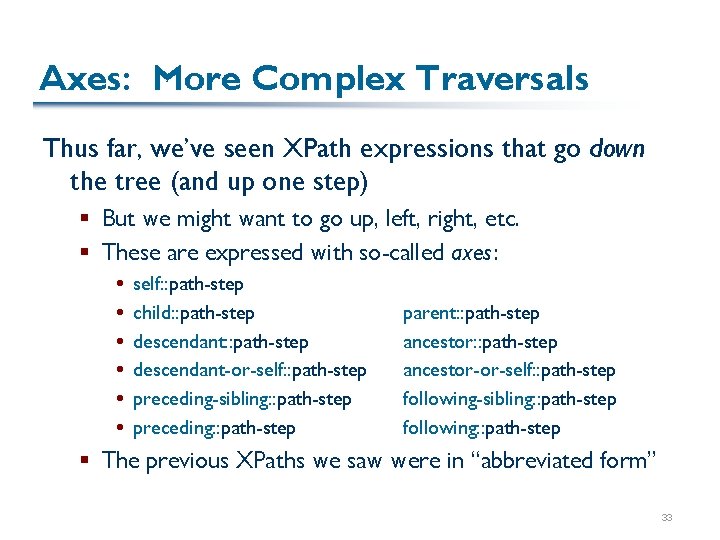

Axes: More Complex Traversals Thus far, we’ve seen XPath expressions that go down the tree (and up one step) § But we might want to go up, left, right, etc. § These are expressed with so-called axes : self: : path-step child: : path-step descendant-or-self: : path-step preceding-sibling: : path-step preceding: : path-step parent: : path-step ancestor-or-self: : path-step following-sibling: : path-step following: : path-step § The previous XPaths we saw were in “abbreviated form” 33

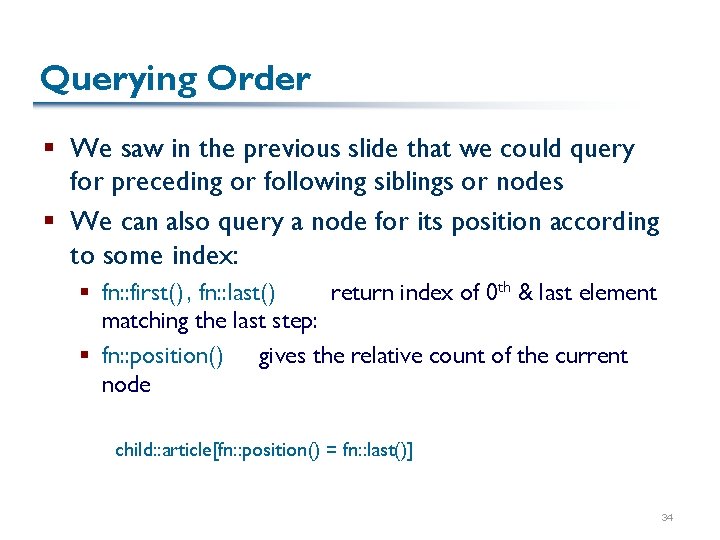

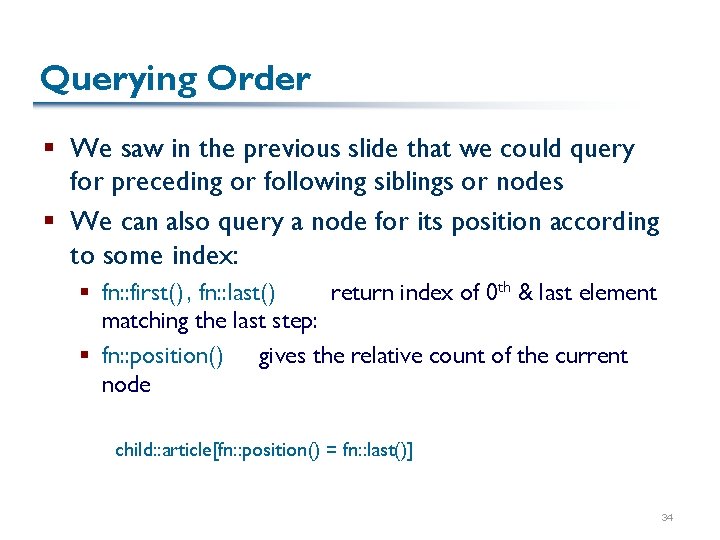

Querying Order § We saw in the previous slide that we could query for preceding or following siblings or nodes § We can also query a node for its position according to some index: § fn: : first() , fn: : last() return index of 0 th & last element matching the last step: § fn: : position() gives the relative count of the current node child: : article[fn: : position() = fn: : last()] 34

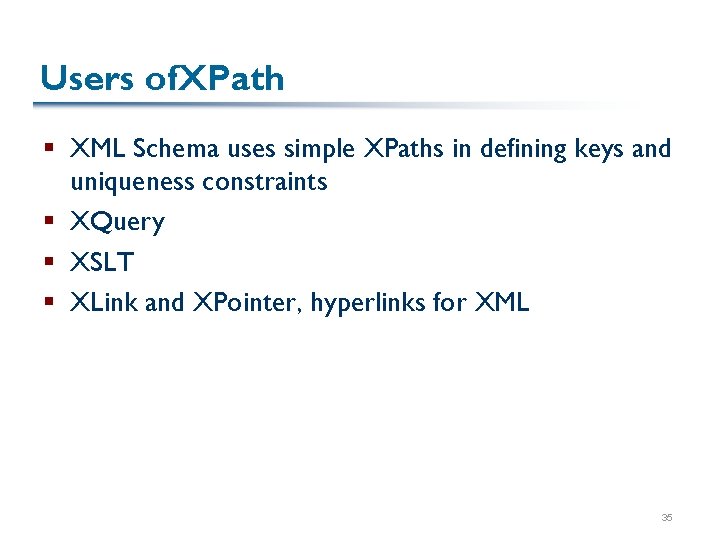

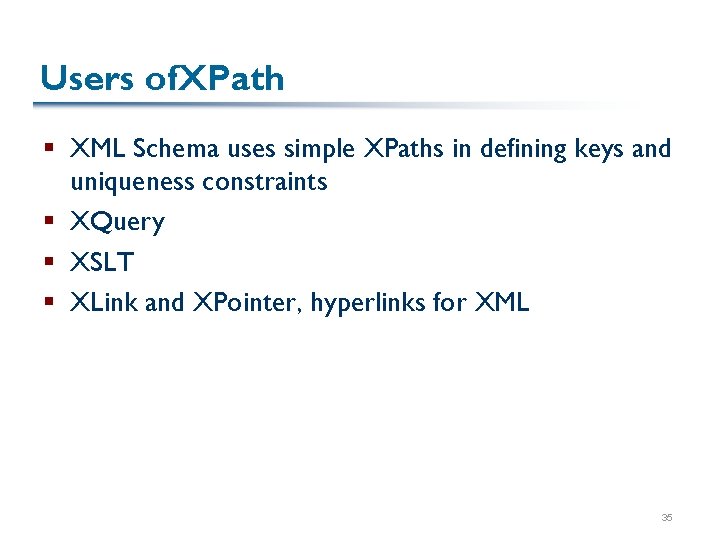

Users of. XPath § XML Schema uses simple XPaths in defining keys and uniqueness constraints § XQuery § XSLT § XLink and XPointer, hyperlinks for XML 35

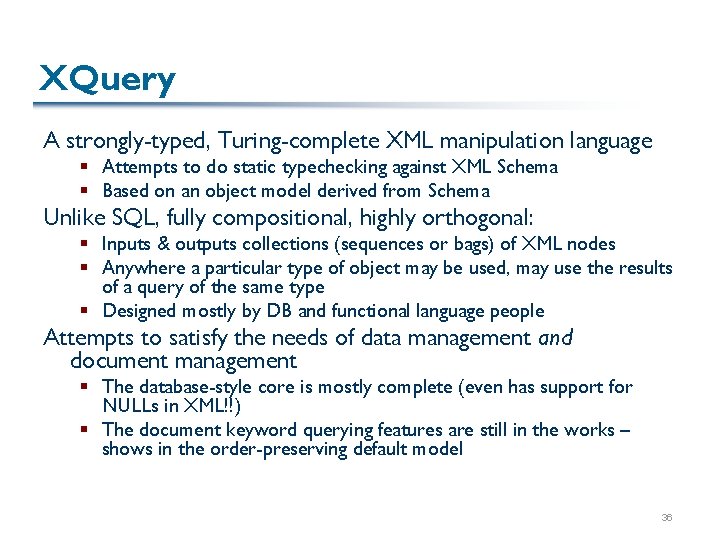

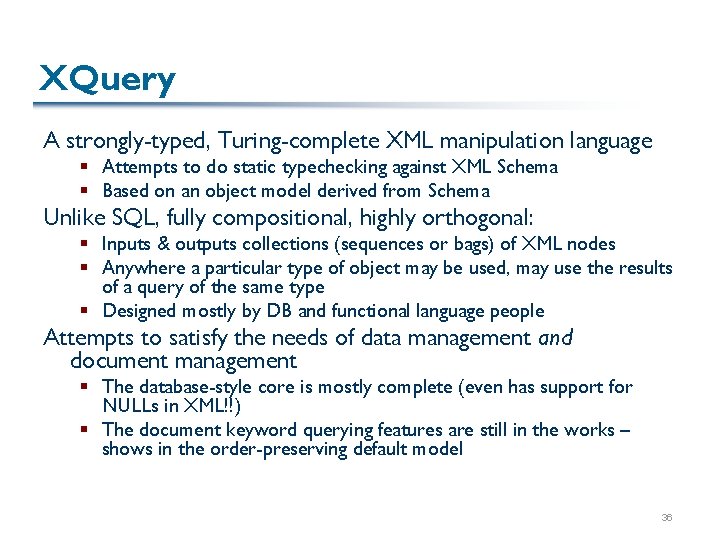

XQuery A strongly-typed, Turing-complete XML manipulation language § Attempts to do static typechecking against XML Schema § Based on an object model derived from Schema Unlike SQL, fully compositional, highly orthogonal: § Inputs & outputs collections (sequences or bags) of XML nodes § Anywhere a particular type of object may be used, may use the results of a query of the same type § Designed mostly by DB and functional language people Attempts to satisfy the needs of data management and document management § The database-style core is mostly complete (even has support for NULLs in XML!!) § The document keyword querying features are still in the works – shows in the order-preserving default model 36

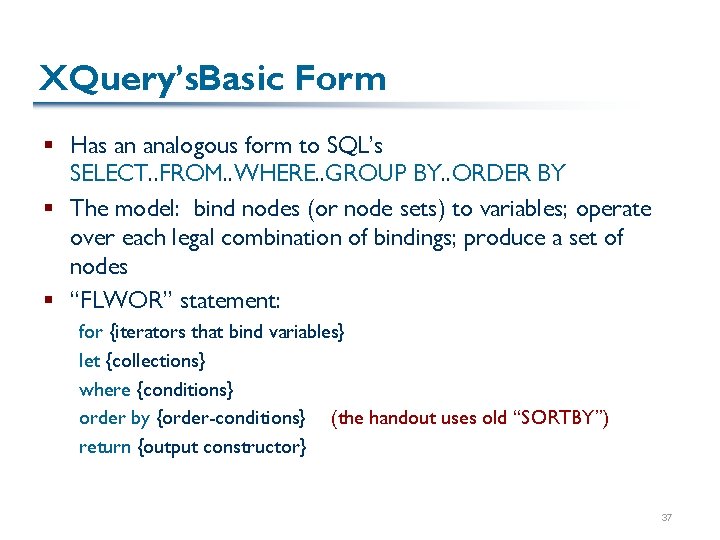

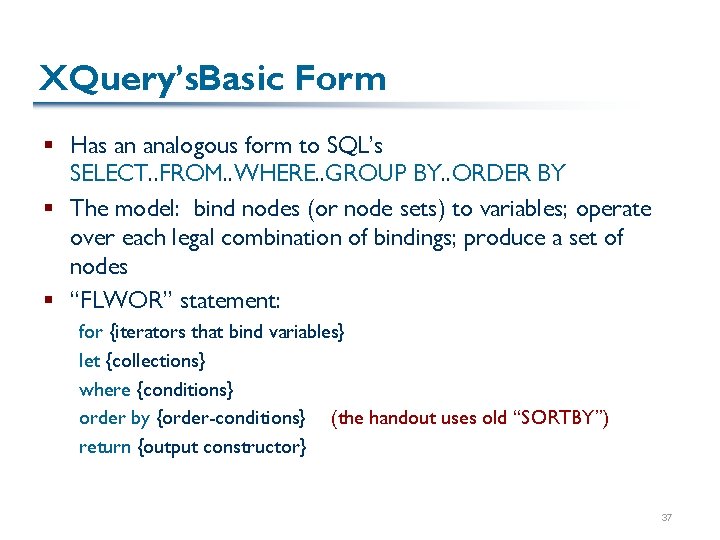

XQuery’s. Basic Form § Has an analogous form to SQL’s SELECT. . FROM. . WHERE. . GROUP BY. . ORDER BY § The model: bind nodes (or node sets) to variables; operate over each legal combination of bindings; produce a set of nodes § “FLWOR” statement: for {iterators that bind variables} let {collections} where {conditions} order by {order-conditions} (the handout uses old “SORTBY”) return {output constructor} 37

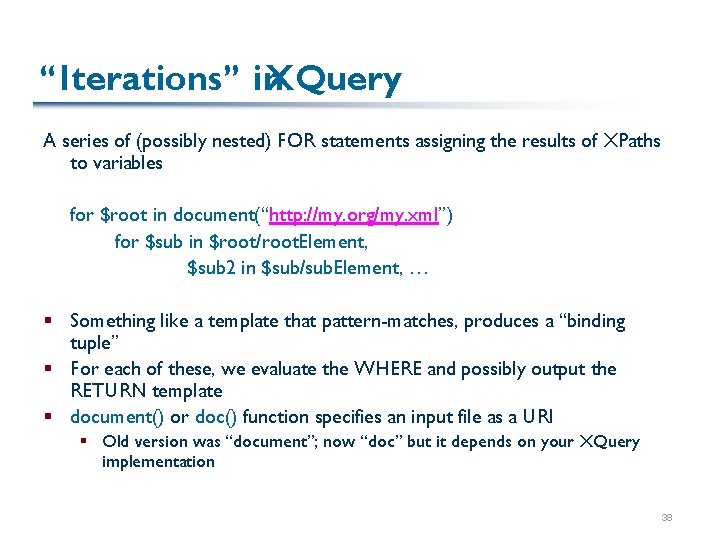

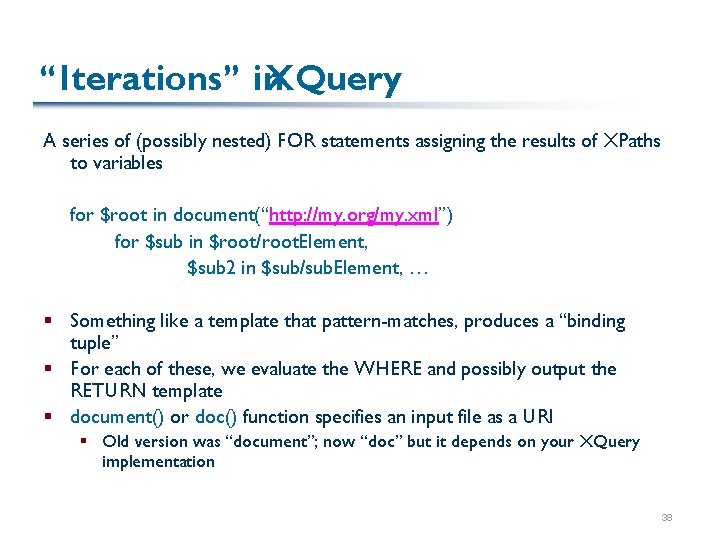

“Iterations” in XQuery A series of (possibly nested) FOR statements assigning the results of XPaths to variables for $root in document(“http: //my. org/my. xml”) for $sub in $root/root. Element, $sub 2 in $sub/sub. Element, … § Something like a template that pattern-matches, produces a “binding tuple” § For each of these, we evaluate the WHERE and possibly output the RETURN template § document() or doc() function specifies an input file as a URI § Old version was “document”; now “doc” but it depends on your XQuery implementation 38

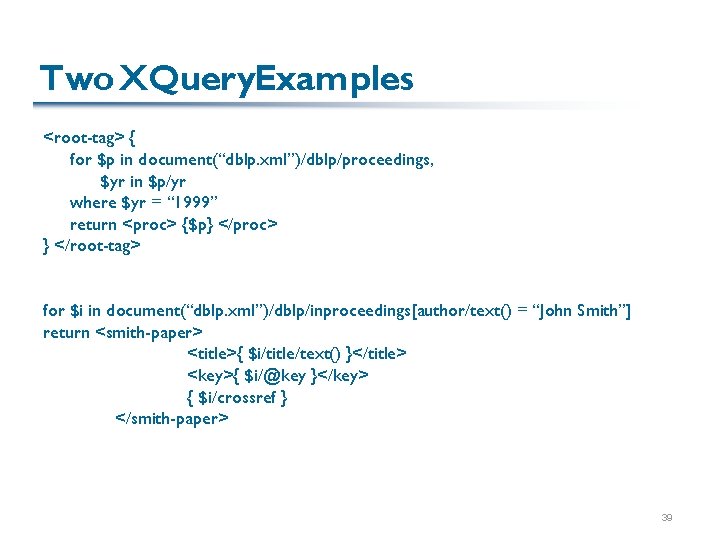

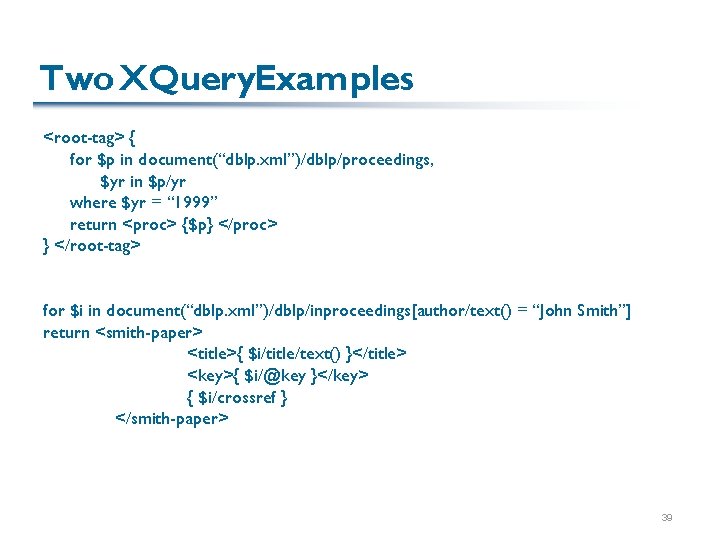

Two XQuery. Examples <root-tag> { for $p in document(“dblp. xml”)/dblp/proceedings, $yr in $p/yr where $yr = “ 1999” return <proc> {$p} </proc> } </root-tag> for $i in document(“dblp. xml”)/dblp/inproceedings[author/text() = “John Smith”] return <smith-paper> <title>{ $i/title/text() }</title> <key>{ $i/@key }</key> { $i/crossref } </smith-paper> 39

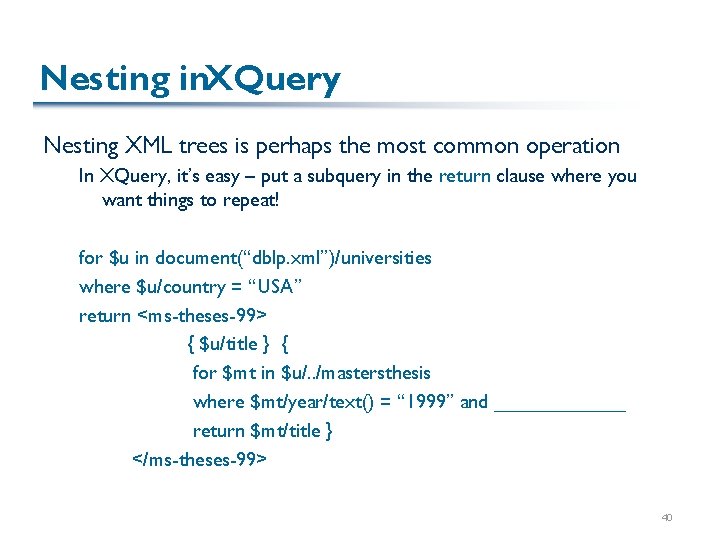

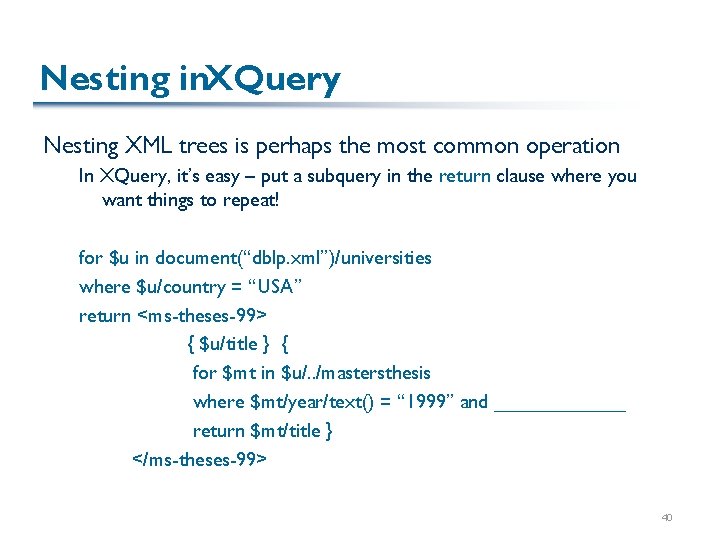

Nesting in. XQuery Nesting XML trees is perhaps the most common operation In XQuery, it’s easy – put a subquery in the return clause where you want things to repeat! for $u in document(“dblp. xml”)/universities where $u/country = “USA” return <ms-theses-99> { $u/title } { for $mt in $u/. . /mastersthesis where $mt/year/text() = “ 1999” and ______ return $mt/title } </ms-theses-99> 40

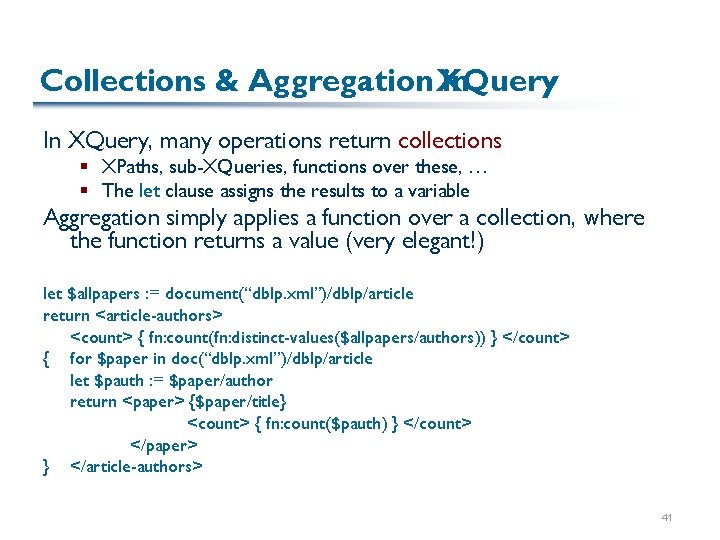

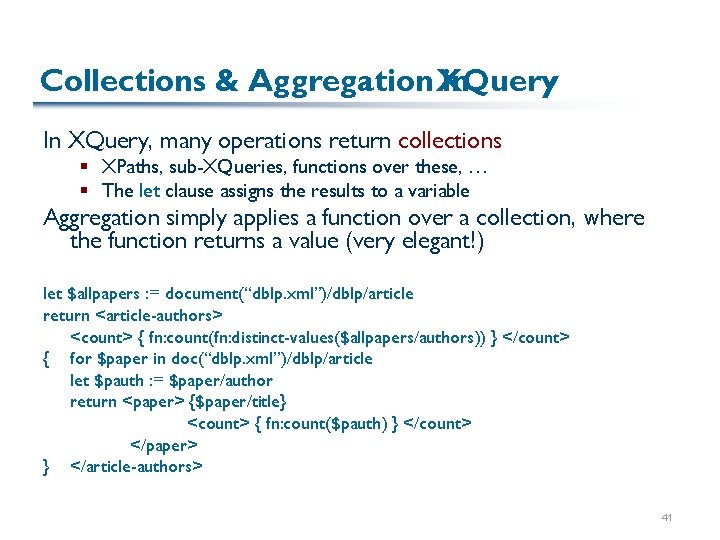

Collections & Aggregation XQuery in In XQuery, many operations return collections § XPaths, sub-XQueries, functions over these, … § The let clause assigns the results to a variable Aggregation simply applies a function over a collection, where the function returns a value (very elegant!) let $allpapers : = document(“dblp. xml”)/dblp/article return <article-authors> <count> { fn: count(fn: distinct-values($allpapers/authors)) } </count> { for $paper in doc(“dblp. xml”)/dblp/article let $pauth : = $paper/author return <paper> {$paper/title} <count> { fn: count($pauth) } </count> </paper> } </article-authors> 41

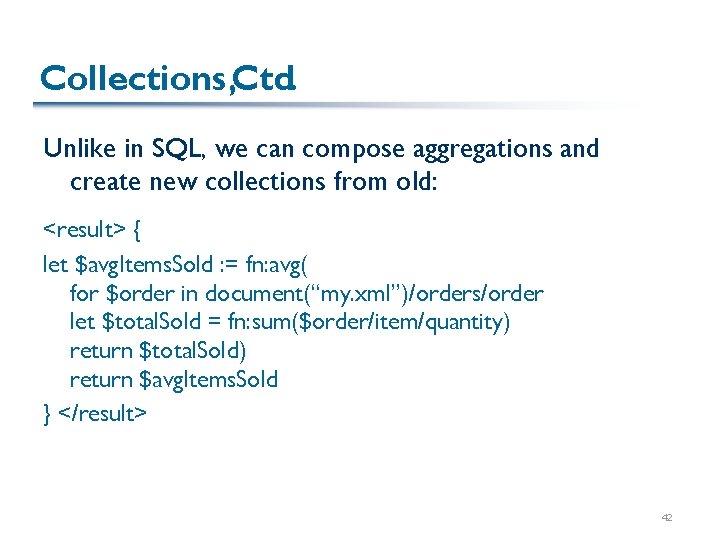

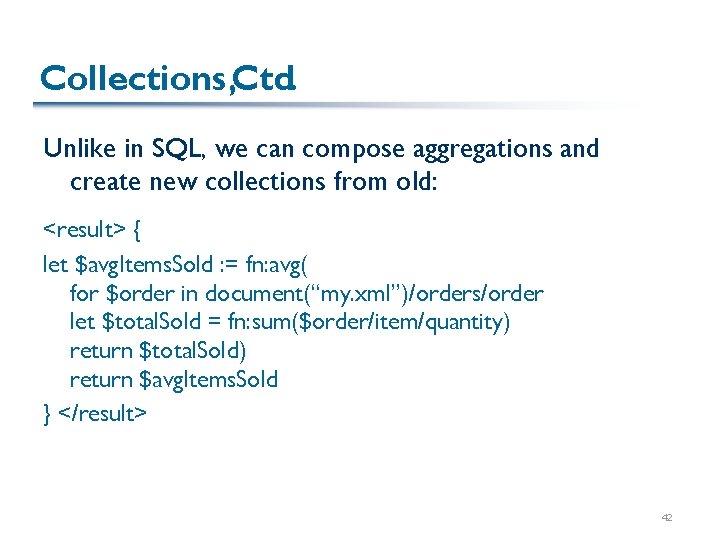

Collections, Ctd. Unlike in SQL, we can compose aggregations and create new collections from old: <result> { let $avg. Items. Sold : = fn: avg( for $order in document(“my. xml”)/orders/order let $total. Sold = fn: sum($order/item/quantity) return $total. Sold) return $avg. Items. Sold } </result> 42

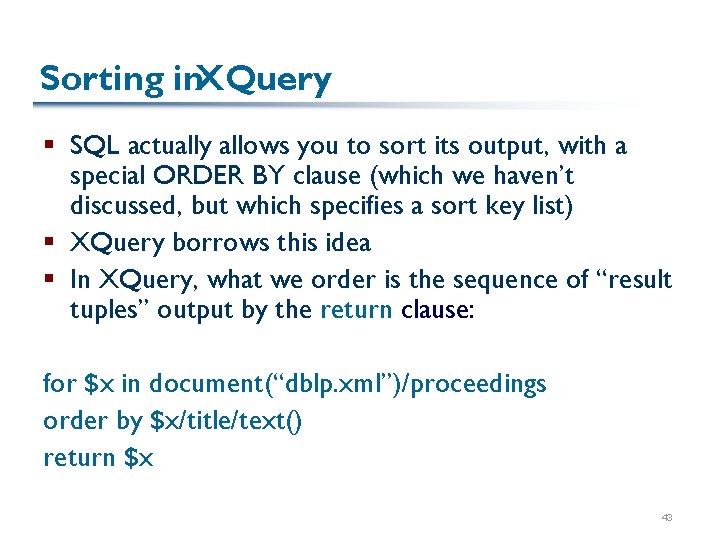

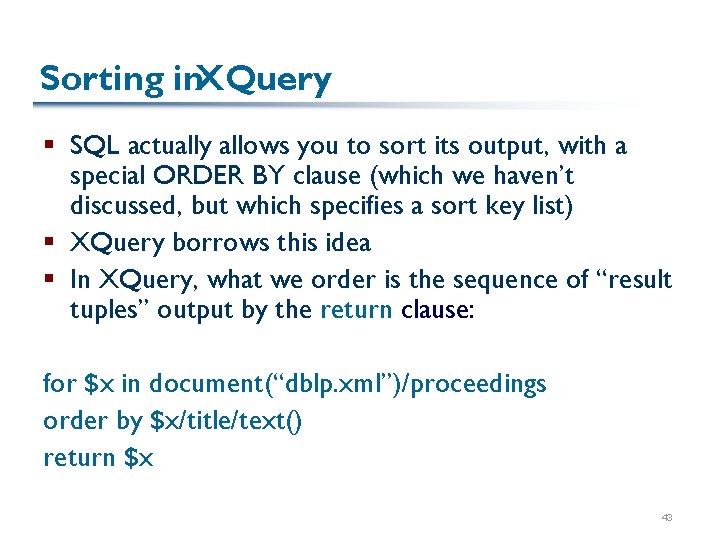

Sorting in. XQuery § SQL actually allows you to sort its output, with a special ORDER BY clause (which we haven’t discussed, but which specifies a sort key list) § XQuery borrows this idea § In XQuery, what we order is the sequence of “result tuples” output by the return clause: for $x in document(“dblp. xml”)/proceedings order by $x/title/text() return $x 43

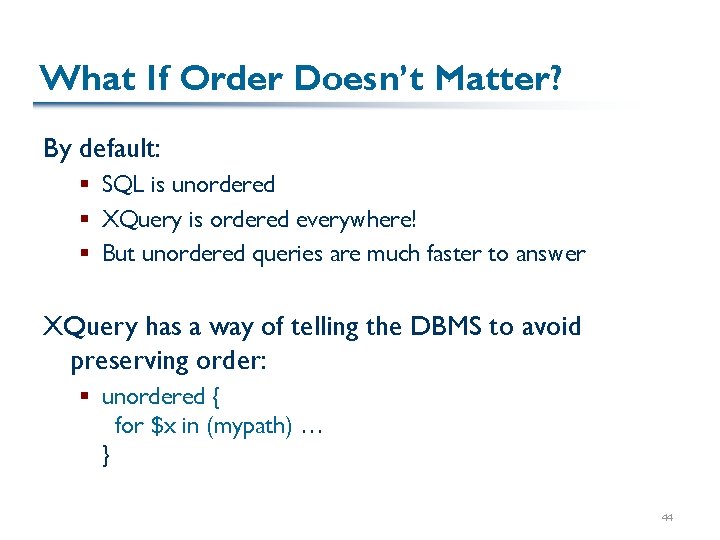

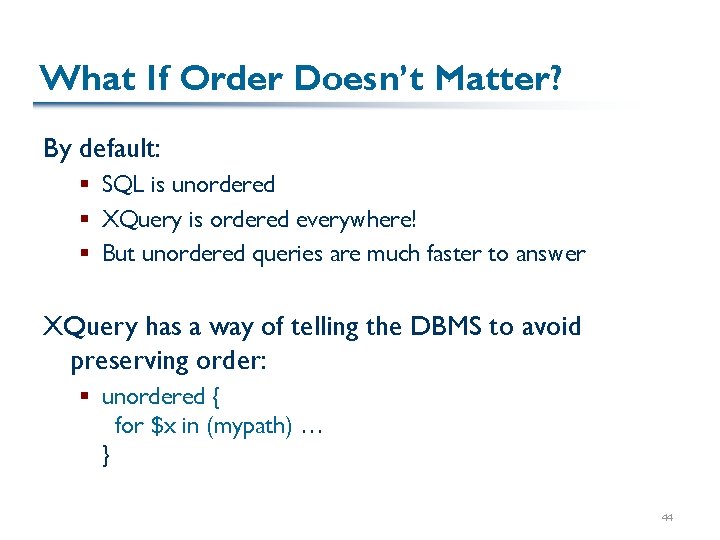

What If Order Doesn’t Matter? By default: § SQL is unordered § XQuery is ordered everywhere! § But unordered queries are much faster to answer XQuery has a way of telling the DBMS to avoid preserving order: § unordered { for $x in (mypath) … } 44

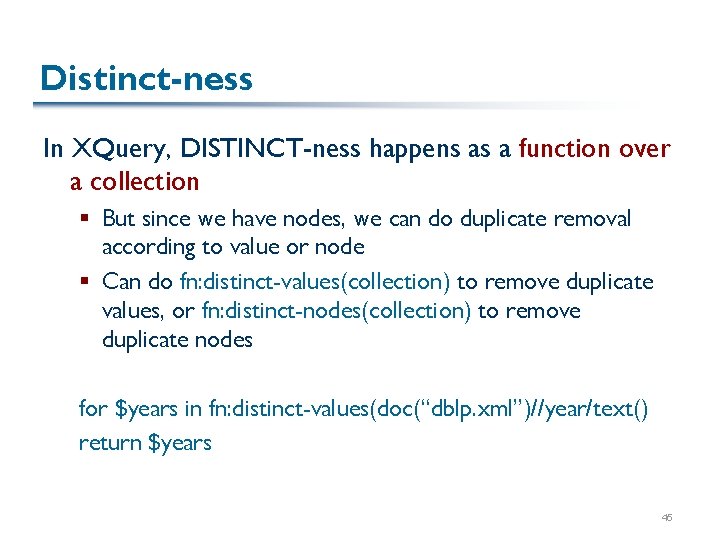

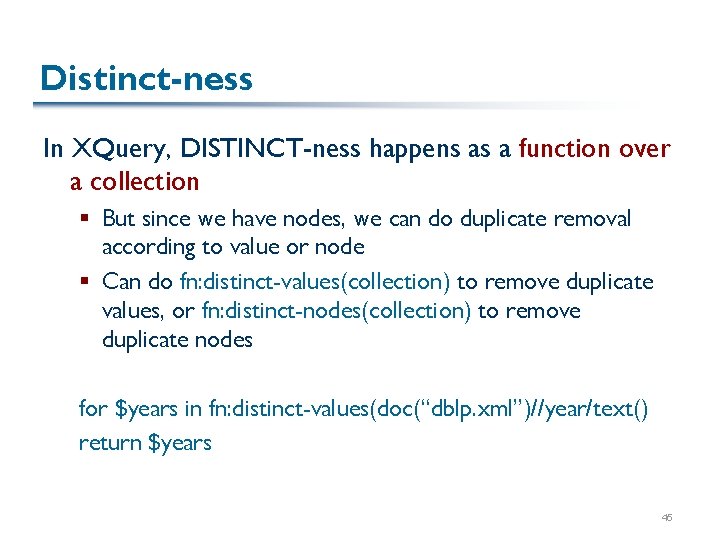

Distinct-ness In XQuery, DISTINCT-ness happens as a function over a collection § But since we have nodes, we can do duplicate removal according to value or node § Can do fn: distinct-values(collection) to remove duplicate values, or fn: distinct-nodes(collection) to remove duplicate nodes for $years in fn: distinct-values(doc(“dblp. xml”)//year/text() return $years 45

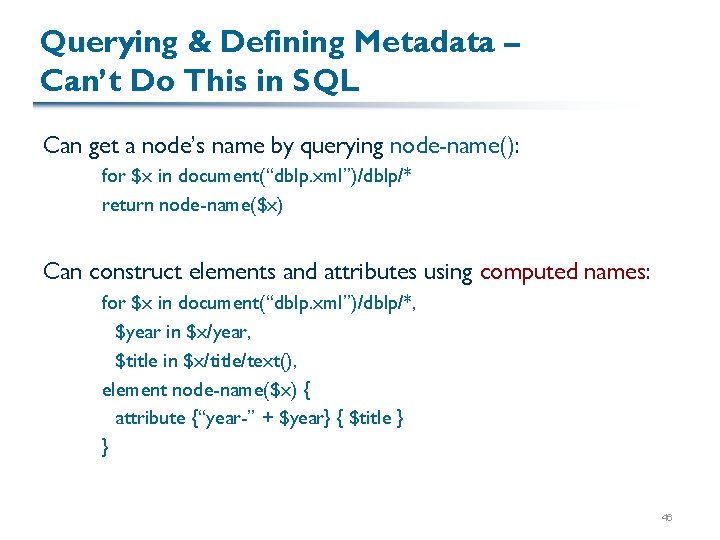

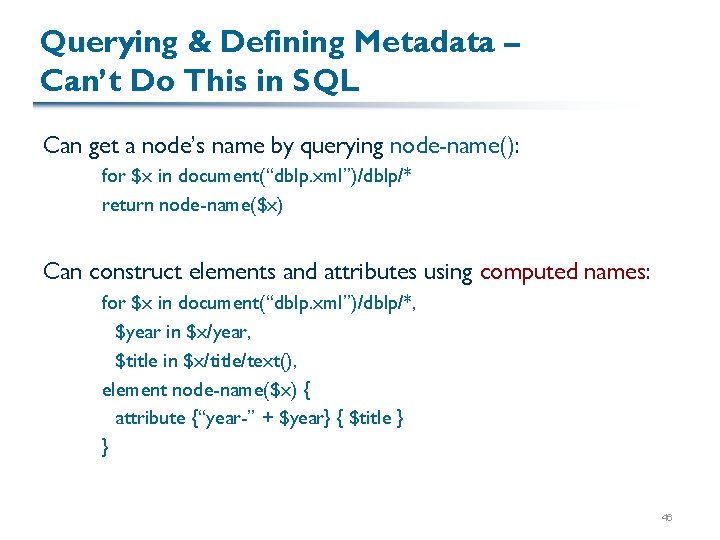

Querying & Defining Metadata – Can’t Do This in SQL Can get a node’s name by querying node-name(): for $x in document(“dblp. xml”)/dblp/* return node-name($x) Can construct elements and attributes using computed names: for $x in document(“dblp. xml”)/dblp/*, $year in $x/year, $title in $x/title/text(), element node-name($x) { attribute {“year-” + $year} { $title } } 46

XQuery. Summary Very flexible and powerful language for XML § Clean and orthogonal: can always replace a collection with an expression that creates collections § DB and document-oriented (we hope) § The core is relatively clean and easy to understand Turing Complete – we’ll talk more about XQuery functions soon 47