Writing a historical essay Jorge Cham PHD Comics

- Slides: 25

Writing a historical essay © Jorge Cham ‘PHD Comics’ 7/28/2014 accessed at http: //phdcomics. com/comics/archive. php? comicid=1734 on 20 October 2017

What Makes a Good Essay? • Argument! Evidence! Argument! • Structure • Clarity • Writing • References Top Tip: Prepare, don’t panic!

Framing your essay: Defining a historical ‘problem’ • Set up a historical problem: what remains unresolved, highly debated, or unknown about the topic you intend to discuss? • If ‘an argument is something someone could reasonably disagree with, ’ what will your argument be? • State your argument as clearly as possible at the beginning of your essay. This is you ‘thesis statement’

Tips When you are framing your argument, think about these things: • How long can my essay be? Reason: shorter essay lengths limit the space you have to make and prove your argument; you need lots of space to develop and support controversial claims and/or very broad arguments. • What kind of evidence do I need to address this topic? Reason: some very good and interesting historical questions may not be answerable with the evidence we have available to us, or the evidence that you can access readily. • How much time do I have? Reason: as well as researching your essay, you need to leave time for developing a structure; checking that you have appropriate evidence to support each claim; revising for clarity and to improve your argument; and PROOF-READING.

Exercise: Frame an essay about the French Revolution: 1. What ‘historical problem’ do you want to address? (Remember: this involves defining a topic that is ‘unresolved’, ‘highly debated’, or ‘unknown’. ) 2. Once you have picked your historical problem, think about what you want to argue. (Remember: you need to assert a claim with which others COULD disagree. Your essay will convince the reader to agree with your perspective. ) 3. Write your thesis statement. (This can take the form of a question, but use this technique sparingly. ) With the person next to you, please define a relevant historical problem, choose an argument, and draft a thesis statement.

Support your argument with evidence • You need empirical evidence to support your argument. This includes material drawn from scholarly secondary sources (that is, evidence drawn from books and articles written by professional historians and other research professionals) AND – especially as you progress into years 2 and 3 – material drawn from primary sources like historical texts, images, objects and testimony. • Evidence cannot ‘speak for itself’. You need to interpret each piece of evidence you use, to show the reader how it proves your point. • Without evidence to support your argument, it remains a mere assertion!

Terms • An essay which brings together evidence drawn from other scholarly sources is ‘synthetic’. Synthetic arguments can be creative when they bring together information and perspectives that are not usually considered together but the risk is that you just regurgitate established facts or positions. • An essay is ‘analytical’ when you go beyond bringing together the evidence you have drawn from the wider scholarly literature to offer a new interpretation or perspective. You are no longer repeating in your own words what is already known, but challenging, expanding, or re-framing existing knowledge. There are risks here too. For instance, if your research base is narrow, what you are saying may not really be original – and might just be wrong! • An essay is ‘argumentative’ (or ‘polemical’) when it strongly supports one side of a debate. The key to a successful argumentative essay is ensuring that you know and thoroughly address the claims of the opposite side, as well as supporting your own view.

Exercise: Finding evidence… Using thesis statement you generated (or the one we liked best as a group), think about what kinds of evidence you would need to write a convincing essay. • Scholarly evidence: go to JSTOR or Project MUSE, and the Warwick Library catalogue and find one book and at least two different articles covering your topic. (Remember that when you writing your real essays, you will also have lots of useful readings identified in your syllabus!) • Primary source evidence: what kinds of primary sources might be useful? Where might you FIND those pieces of evidence?

Creating a structure for your essay • The logic of your argument creates the structure of your paper. • Be explicit and up-front about the logic (say what you plan to argue and indicate how you will support your argument in the introduction paragraph) • Follow the logic /structure you indicate at the beginning (if it is a long essay or you have a complicated argument, you will want to incude milemarkers) • Make sure that the paper actually argues what you say it will argue in the introduction

Introductions matter! Use the introduction to: • Develop the historical problem the essay will discuss. • Create space for debate and disagreement. For example, point to a debate in the historical literature and say how your argument challenges the literature. • Present your solution to the problem you are dealing with. • Give a sense of how the argument will proceed.

Introductions matter! What not to do in the introduction • Don’t just give a general and factual account of what happened. • Don’t just list arguments by different historians: engage with them. • Keep it focused!

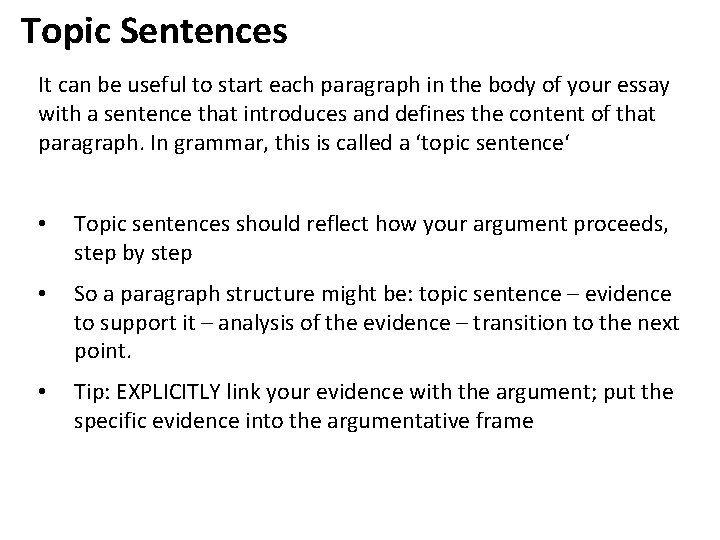

Topic Sentences It can be useful to start each paragraph in the body of your essay with a sentence that introduces and defines the content of that paragraph. In grammar, this is called a ‘topic sentence‘ • Topic sentences should reflect how your argument proceeds, step by step • So a paragraph structure might be: topic sentence – evidence to support it – analysis of the evidence – transition to the next point. • Tip: EXPLICITLY link your evidence with the argument; put the specific evidence into the argumentative frame

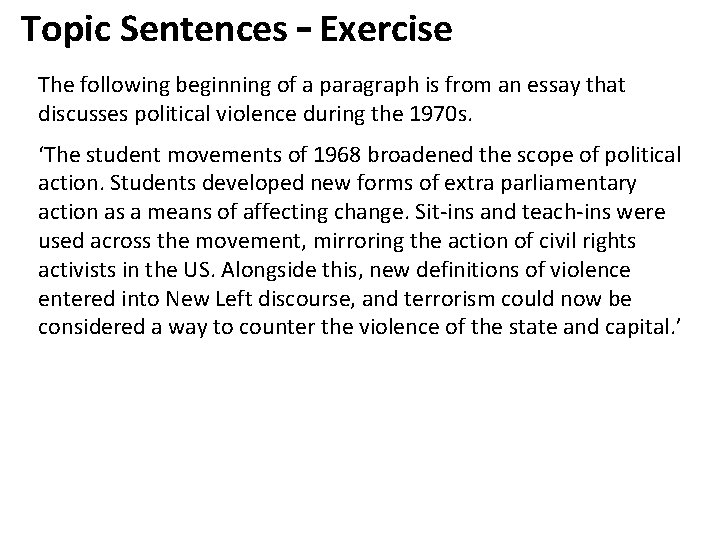

Topic Sentences – Exercise The following beginning of a paragraph is from an essay that discusses political violence during the 1970 s. ‘The student movements of 1968 broadened the scope of political action. Students developed new forms of extra parliamentary action as a means of affecting change. Sit-ins and teach-ins were used across the movement, mirroring the action of civil rights activists in the US. Alongside this, new definitions of violence entered into New Left discourse, and terrorism could now be considered a way to counter the violence of the state and capital. ’

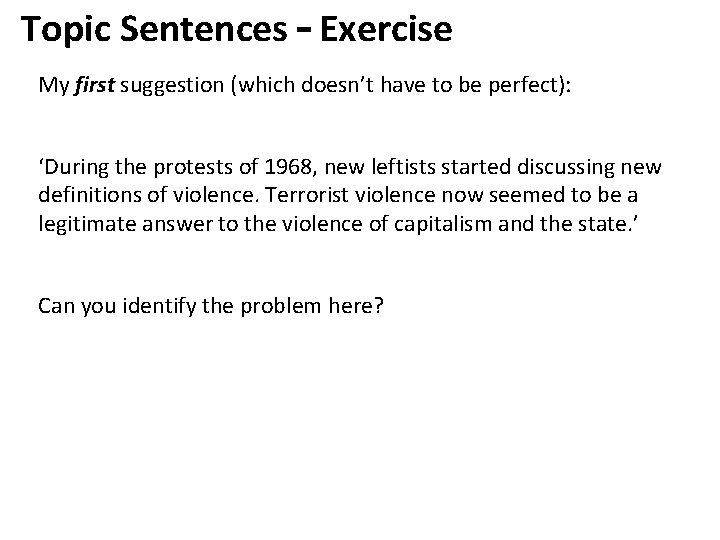

Topic Sentences – Exercise My first suggestion (which doesn’t have to be perfect): ‘During the protests of 1968, new leftists started discussing new definitions of violence. Terrorist violence now seemed to be a legitimate answer to the violence of capitalism and the state. ’ Can you identify the problem here?

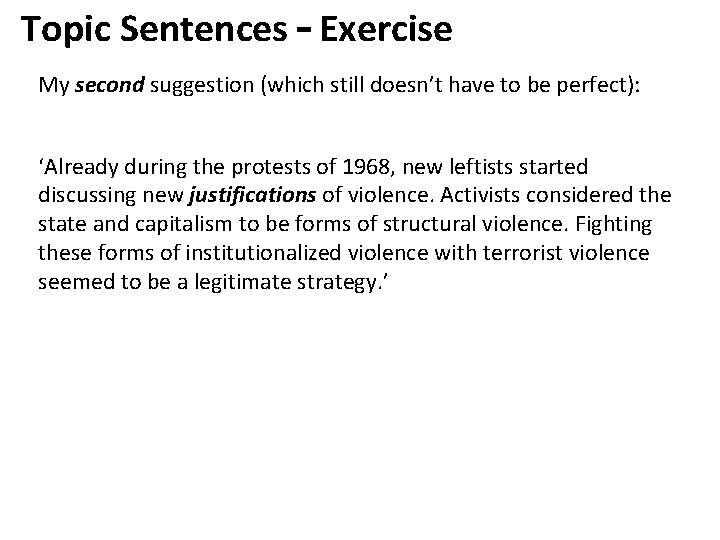

Topic Sentences – Exercise My second suggestion (which still doesn’t have to be perfect): ‘Already during the protests of 1968, new leftists started discussing new justifications of violence. Activists considered the state and capitalism to be forms of structural violence. Fighting these forms of institutionalized violence with terrorist violence seemed to be a legitimate strategy. ’

Please don’t try this at Warwick… Clear writing Is essential! ©Bill Waterson, The Complete Calvin and Hobbes Paperback (Riverside, NJ: Andrews Mc. Meel Publishing, 2012)

Writing – Clear Writing Is Essential! Issues to look out for: • Who are your actors? ‘The UK experienced a period of change that attempted to modernize the country. ’ The subject for ‘attempted’ is ‘change’, but ‘change’ cannot do something. • How are sentences connected? ‘Social Democrats often equated Communists and Nazis. Most people killed during the street fighting in Weimar were Communists. ’ no link between the sentences.

Writing – Clear Writing Is Essential! Things to avoid • Long and complicated sentences. If you can write concise sentences, do so. They are easier to read. Long and complicated sentences do not make you sound smart! • Long and complicated paragraphs. My rule of thumb is: 250 -300 words per paragraph. If your paragraph has more than 400 words, there is usually a problem. It’s easy to check! • A paragraph should focus on one key idea that you present at the beginning of the paragraph with a topic sentence. Make sure that you keep focusing on this idea. If you introduce a new idea, consider starting a new paragraph.

Writing – Clear Writing Is Essential! Things to avoid • Passive voice – ‘it is argued that’ or ‘it will be shown that’; ‘this view was criticised’. If you wonder why we discourage passive voice, think about this sentence: ‘Chips were eaten by Fred. ’ Not only does it sound awkward, but it uses two more words than ‘Fred ate chips’. So use active verbs. • Generalisations – ‘historians have argued’; ‘critics have written’: WHICH historians or critics?

Writing – Clear Writing Is Essential! More things to avoid: ‘Potential argument’: ‘It could be argued …’ – We want to know what you argue! ‘I feel’ – tutors differ whether you can use ‘I’ or not, but do not talk about your feelings or opinions. We want to know your well-supported arguments.

Writing – Clear Writing Is Essential! And some more things to avoid: ‘Therefore’ (and also ‘thus’) where it does not belong. ‘Therefore’ implies a causality. Make sure you actually talk about causalities when you use ‘therefore’. Repetitions – both in terms of content and in terms of word choice. Pseudo-paraphrasing: this is when you borrow text from another author, changing only a few words from the original to ‘make it your own’. THIS IS A SUBTLE FORM OF PLAGIARISM, and many students do it inadvertently.

Writing – correct English is essential too! • Avoid sentence fragments. A complete sentence includes a subject (generally a noun or pronoun) and a predicate (at least a verb). It does not depend on the preceding or following sentence to make sense • Avoid contractions (It is, not It’s; cannot can’t) • Take care with possessives and plurals. Its is the correct equivalent of his and hers for non-human subjects (‘The guillotine performed its gruesome task. ’) Plural nouns should be made possessive with a final apostrophe, not an apostrophe s (‘The cats’ tails were tangled’. ) • USE SPELL-CHECK and GRAMMAR CHECK – but remember that these tools won’t find EVERY mistake (think about ‘public’ and ‘pubic’ for example…)

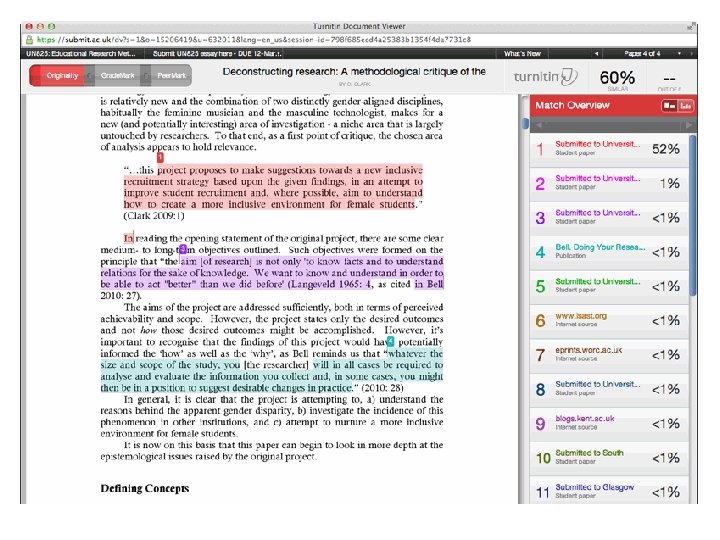

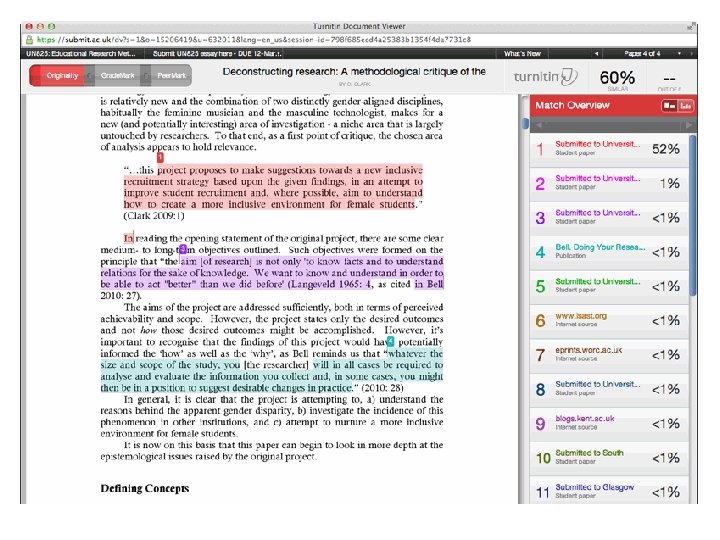

Why avoid plagiarism? Well… • Intellectual integrity and honesty is a crucial part of scholarly culture. Theft of ideas and their expression is theft. • The tool YOU will experience directly is an anti-cheating software system called Turnitin • Presumptions of intellectual integrity and honesty are baked in to the degree classification system. It would be unfair for cheaters to receive the same marks and degrees as students who are honest. • How does Turnitin work? It digitally adds and compares your essays to both published works and a huge and growing international database of essays submitted by students year-onyear. All similarities (including pseudo-plagarism) are identified for your markers to assess whether or not they constitute cheating. • Therefore, the University has invested heavily in tools to catch plagiarism and other forms of cheating (like buying essays).

Resources: • First stop should be the Department’s own advice in your Handbook and here: https: //www 2. warwick. ac. uk/fac/arts/history/students/refe rencing/ • The University curates a whole range of useful online courses to support you as researchers and writers. You can find some of these here: https: //www 2. warwick. ac. uk/services/skills/pgr/elearning • Beyond the University, you can also find great advice from other historians. One site that offers useful practical advice for students from a teaching historian is Dr. George Gosling’s blog: https: //gcgosling. wordpress. com/advice/