WorkinProgress Capital Costs and Tradeoffs Robert W Grubbstrm

Work-in-Progress, Capital Costs and Tradeoffs Robert W. Grubbström FVR RI, FLO K Linköping Institute of Technology, Sweden Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Studies, Šempeter pri Gorici, Slovenia robert@grubbstrom. com Keynote Address, XVI SUMMER SCHOOL "FRANCESCO TURCO" Abano, September 14 -16, 2011

To Alessandro and all Italian Colleagues and Friends: Thank you very much for inviting me and my wife Anne-Marie to the XVI SUMMER SCHOOL "FRANCESCO TURCO"

The Italian Marquis and engineer Vilfredo Pareto, 1848 -1923, was born i Paris. He wrote a thesis in solid mechanics with the title Principes fondamentaux de l’équilibre de corps solides, which he defended at the Technical University of Turin in 1869. He was appointed ”ordinary” Professor of economie politique at the University of Lausanne in 1894. He created ”Pareto’s law”, which later has become known as the ” 80/20 -rule”. He contributed to the foundation of welfare economics, by defining optimality in an economic system as a state from which no one can become better off without somebody else becoming worse off (Pareto Optimality).

The First Industrial Engineer Vilfredo Pareto, 1848 -1923

Abstract Production is the transformation from one set of resources into a second set of – hopefully - more valuable resources. This transformation takes time and creates a need for capital with consequential capital costs, since resources are utilised before resulting products are in place. In the meantime resources are earmarked as work-in-progress. This keynote lecture discusses the methodology for determining capital costs from a financial point of view enabling the capital costs of work-in-progress to be evaluated in a compatible way as any other capital costs pertaining to investments in general. The main emphasis is laid on thesis that payments are the ultimate consequences of economic activities. Therefore for determining the true capital costs, monetary payments should be traced and measured as closely as possible as to their amount, timing and risk. Topics to be included are tradeoffs between work-in-progress and capital costs, and methodology for determining capital costs for production with complex structures including recycling activities, dynamic lotsizing, inter alia. The traditional Average Cost (AC) method is contrasted with the Net Present Value (NPV) principle and its related Annuity Stream measure.

Today’s Agenda ØBrief on financial methodology ØApplication to EOQ/EPQ problem types ØDynamic lotsizing ØMRP systems ØRecycling ØBalancing Queueing and Capacity Costs ØConclusions

Brief on Financial Methodology

(i) Arguments for emphasising monetary streams (rather than cost assumptions) • The ultimate economic consequences of all activities in a company are in the form of monetary streams. This is the closest one can come to measuring the real economic performance of the firm. • This is emphasised in particular, when a company is created, and when it is on the verge of collapsing. • Modern legislation stresses the need to keep track of monetary consequences, for instance by requiring a statement of changes in financial position. • Overwhelming theory requires that cash flows should be evaluated by their resulting Net Present Value (NPV), or by some equivalent measure such as their corresponding Annuity Stream.

(i) Arguments for using continuous time (rather than discrete time) • A discrete time scale is embedded in a continuous time scale, so continuous time is more general. • Globalisation makes time more continuous than before from a practical point of view. • Often it is easier to solve problems with continuous variables. • In discrete problems, there might be periods with no events, but empty periods do not exist in continuous time.

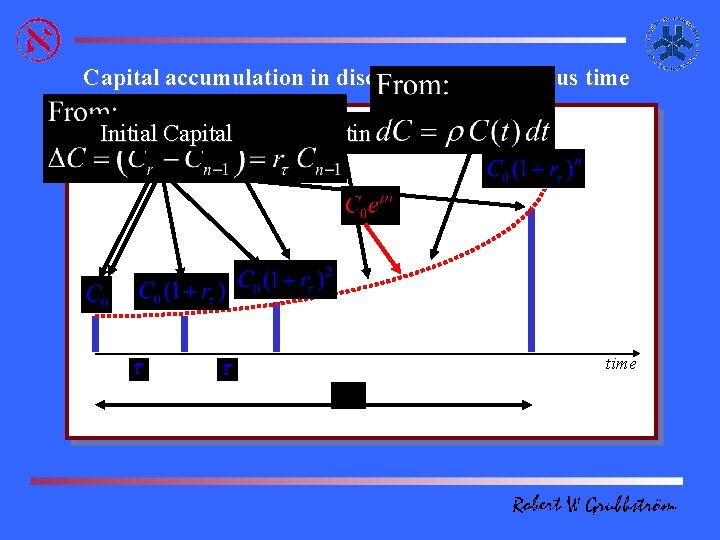

Capital accumulation in discrete and continuous time Initial Capital Discrete Continuous time

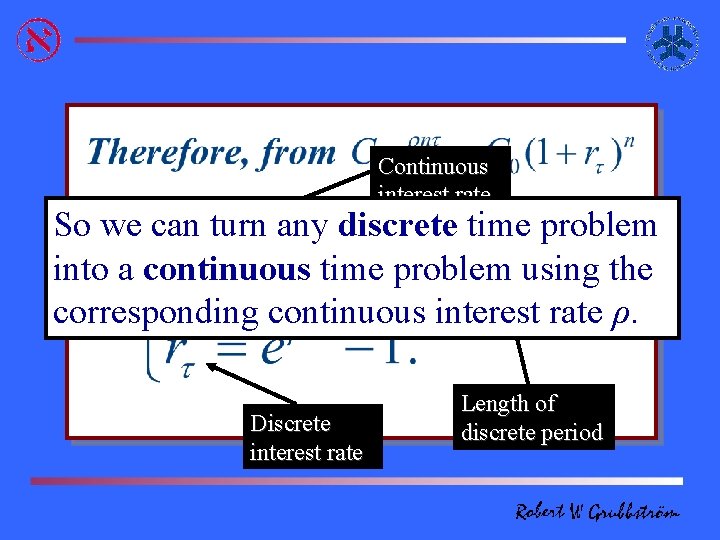

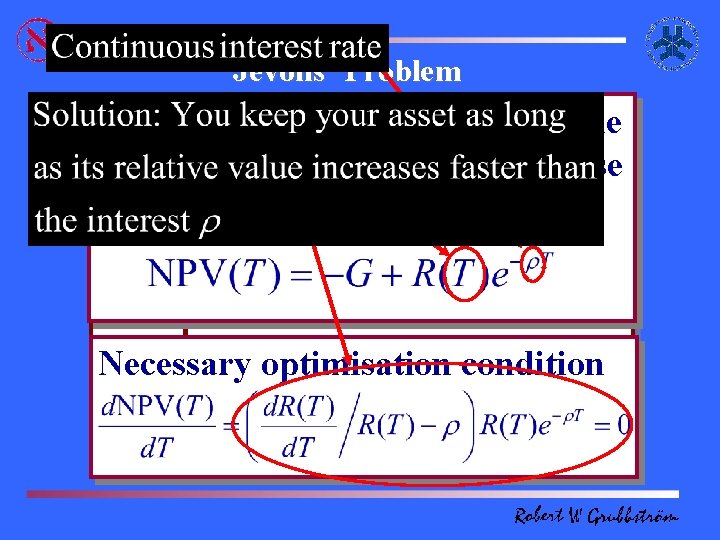

Continuous interest rate So we can turn any discrete time problem into a continuous time problem using the corresponding continuous interest rate ρ. Discrete interest rate Length of discrete period

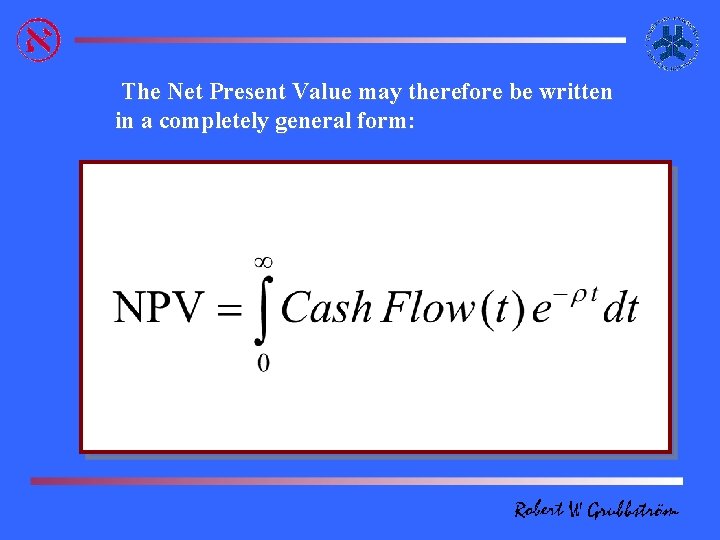

The Net Present Value may therefore be written in a completely general form:

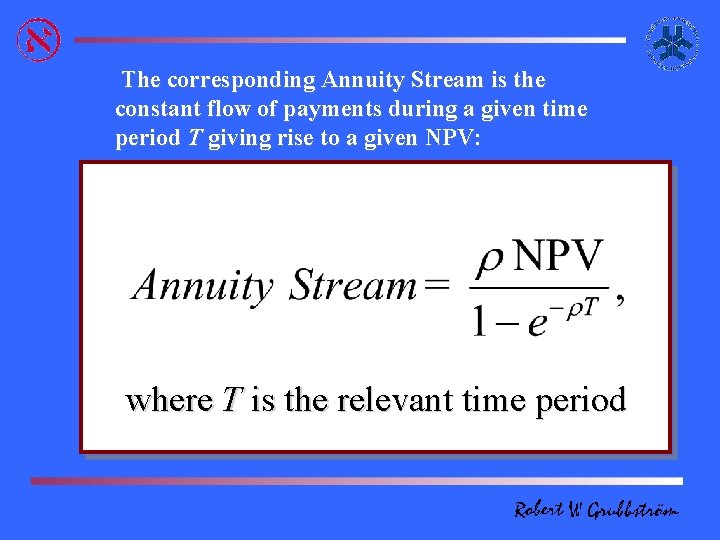

The corresponding Annuity Stream is the constant flow of payments during a given time period T giving rise to a given NPV: where T is the relevant time period

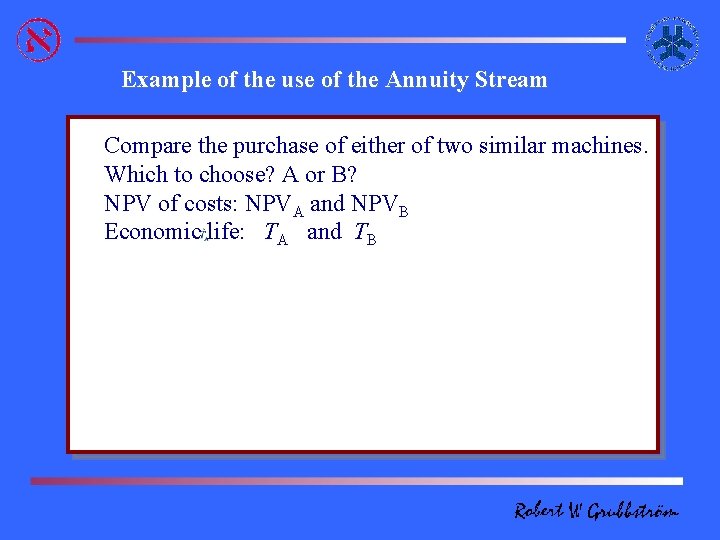

Example of the use of the Annuity Stream Compare the purchase of either of two similar machines. Which to choose? A or B? NPV of costs: NPVA and NPVB Economic life: TA and TB Choose the one with the lowest of:

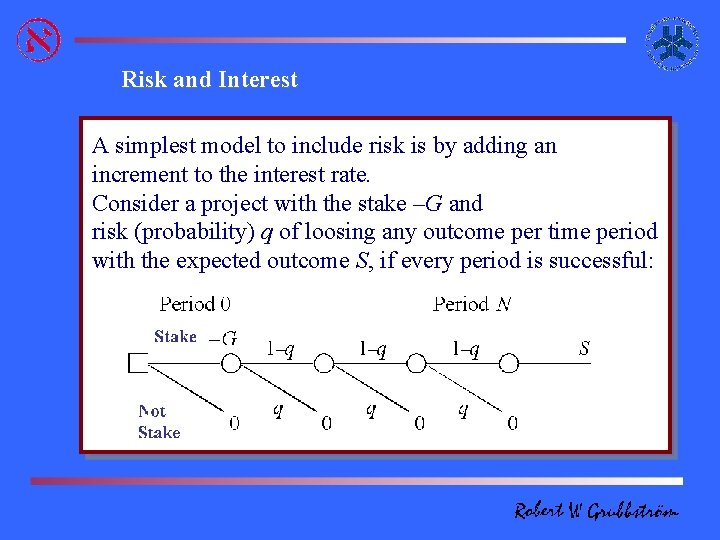

Risk and Interest A simplest model to include risk is by adding an increment to the interest rate. Consider a project with the stake –G and risk (probability) q of loosing any outcome per time period with the expected outcome S, if every period is successful:

Risk and Interest II The project is successful with the probability (1 -q)-N yielding the outcome S. Assume that the project outcome grows with time N. This is a simple interpretation of the according to S = G(1+r) to tradeoff between The interest increment r The expected NPV then becomes compensating risk q is risk (security) and interest therefore for a risk-neutral person. So if

Application to EOQ/EPQ Problems

Hadley, G. , A comparison of order quantities computed using the annual cost and the discounted cost, Management Science, 10(3), 1964, 472 -476.

Grubbström, R. W. , A principle for determining the correct capital costs of inventory and work-in-progress, IJPR, 18(2), 1980, 259 -271.

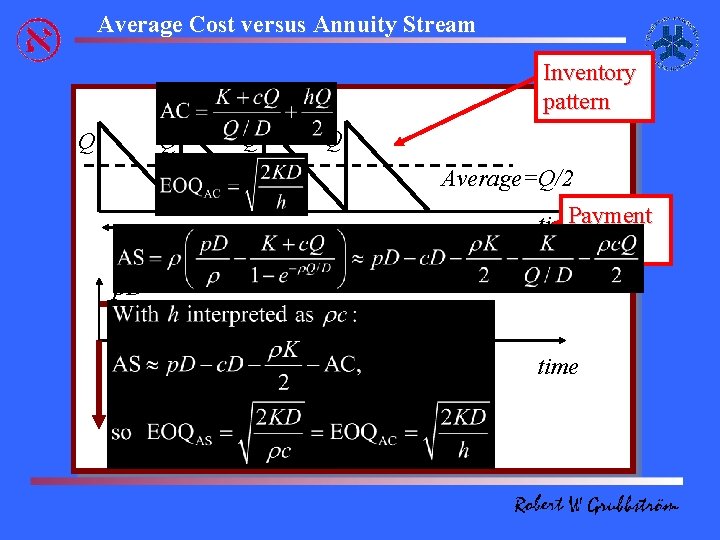

Average Cost versus Annuity Stream Inventory pattern Q Q Average=Q/2 time. Payment streams Q/D p. D time -K-c. Q

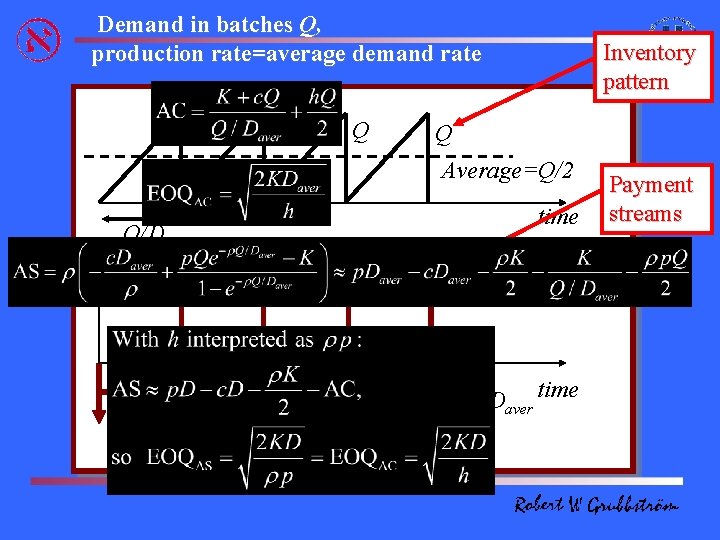

Demand in batches Q, production rate=average demand rate Q Q Q Inventory pattern Q Average=Q/2 time Q/Daver p. Q -K -K p. Q -c. Daver time Payment streams

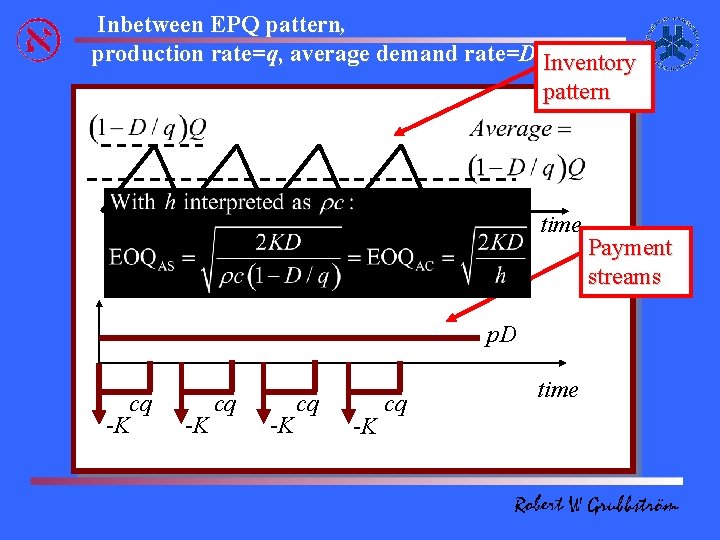

Inbetween EPQ pattern, production rate=q, average demand rate=D Inventory pattern time Q/D p. D cq -K -K cq time Payment streams

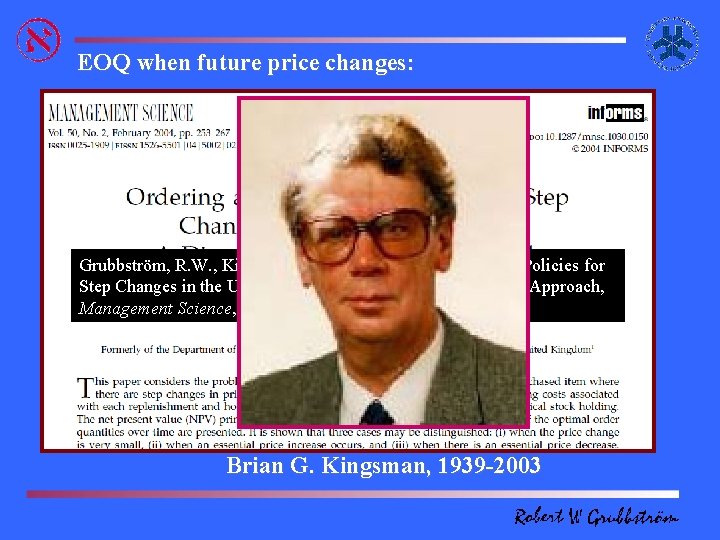

EOQ when future price changes: Grubbström, R. W. , Kingsman, B. G. , Ordering and Inventory Policies for Step Changes in the Unit Item Cost: A Discounted Cash Flow Approach, Management Science, 50(2), 2004, 253– 267. Brian G. Kingsman, 1939 -2003

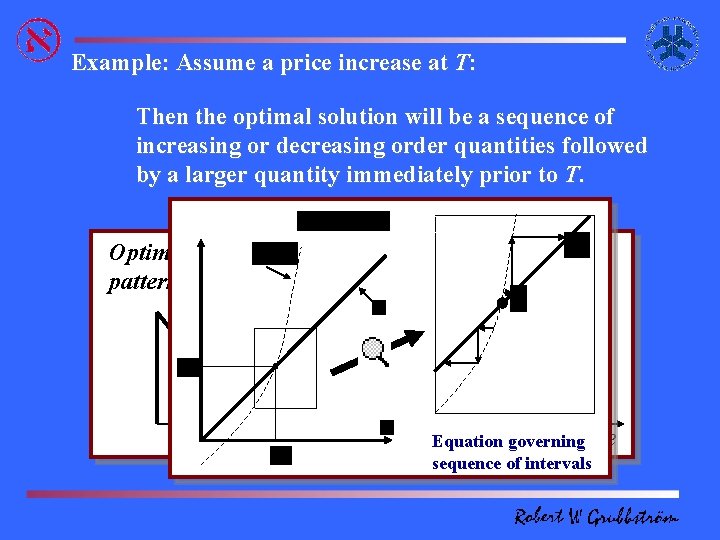

Example: Assume a price increase at T: Then the optimal solution will be a sequence of increasing or decreasing order quantities followed by a larger quantity immediately prior to T. Optimal inventory pattern Stationary sequence at new price T time Equation governing sequence of intervals

The Classical Newsboy Problem

Background The Newsboy (Newsvendor) problem is probably the simplest of all stochastic inventory problems, involving a one-time purchase decision and a stochastic sales outcome. As an investment, it can be interpreted as the simplest stochastic version of the point-in, point-out investment problem of William Stanley Jevons (1871). William Stanley Jevons 1835 -1882

Bertrand Russel: Forethought – Which involves doing unpleasant things now for the sake of pleasant things in the future, is one of the most important marks of the development of man. Bertrand Russel 1872 -1970

Jevons’ Problem To choose the optimal time for the asset to mature, which is to choose T that Time maximises Reward of investment T R(T) Outlay Necessary optimisation condition -G

A Newsboy problem with Compound Renewal Demand One of simplest business problems is when you bring a bundle of products to the market place, but you don’t know how much to bring. If too much, then you’ll have a loss from discarding the leftovers, and if to few, you will loose customers to someone else. This is the classical Newsboy problem. But life can be much more complicated. Your customers may come at intervals to your outlet, and they each require different amounts. Here, there are two uncertainties, one concerning the timing, and one concerning the amounts. However, this second much more involved situation can be modelled in exactly the same way as the first simple case, if the probability distribution is designed in a special way and you want to maximise your Net Present Value.

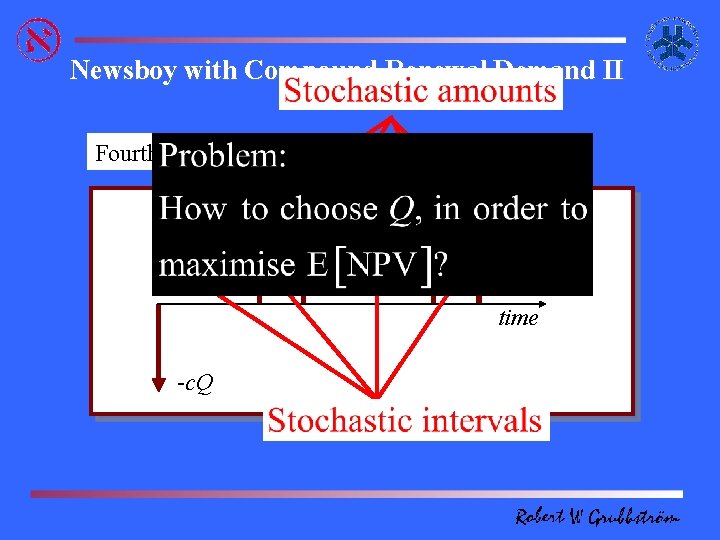

Newsboy with Compound Renewal Demand II First customer arrives buying Second customer arrives buying Third customer arrives buying Fourth customer arrives buying Buy/make/purchase Q items DD 1 DD items 3 items 4 items 2 items time -c. Q

Grubbström, R. W. , The Newsboy problem when customer demand is a compound renewal process, EJOR, 203(1), 2010, 134 -142.

Time reference point for discounting Very recent article suggesting an explanation to differences in Average Cost Approach and Beullens, P. , Janssens, G. K. , Holding Costs under Push or Pull Conditions Annuity Stream Principle for - The Impact of the Anchor Point, EJOR, 215(1), 2011, 895 -908. EOQ/EPQ models

Dynamic Lotsizing

Background The Wagner-Whitin (optimal, 1958) and the Silver-Meal (heuristic, 1973) algorithms for dynamic lotsizing are normally presented in terms of an average cost function in discrete time. An additional forward optimal dynamic lotsizing algorithm has been presented • Single product recently called the Triple Algorithm. This new algorithm may be applied either time is discrete or • No backlogging allowed continuous, and either the traditional average cost or the Net • Finite horizon Present Value (Annuity • Given requirements di Stream) is the objective function. at given times ti

Problem To choose the amount to produce (or not to produce) at each time satisfying given requirements and optimising an objective function (NPV or AC)

Obvious observations (i) When the setup cost K is very high compared to the holding cost h, there can only be one setup at the very beginning of the process (the All-At-Once, @1, solution). (ii) With a very low setup cost K, there must be a setup at every time a non-zero requirement occurs (the Lot-For-Lot, L 4 L, solution). Therefore, the domain in which dynamic lotsizing exists as a non-trivial problem, is when this ratio is neither high, nor low.

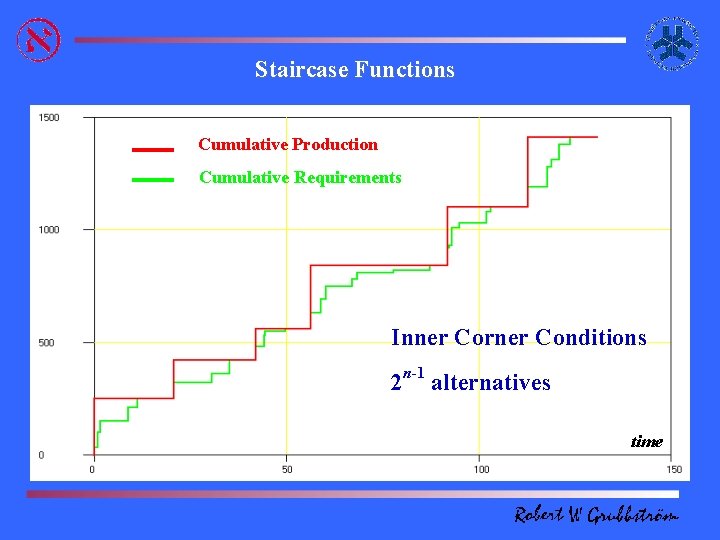

Inner Corner Property The Inner-Corner Condition is. Cannot valid be foroptimal! either for optimality) Discrete(necessary or Continuous Time problems and either the Average Cost Approach or the NPV/Annuity Stream This turns the Principle is used. requirements Dynamic Lotsizing Problem production Furthermore, this condition applies also to production into a zero/one problem: any Multi-Product Assembly System with inner corner contact To Produce Not to Produce arbitrarily complexor. Product Structures. time

Grubbström, R. W. , Bogataj, M. , Bogataj, L. , Optimal Lotsizing within MRP Theory, Annual Reviews in Control, 34(1), 2010, 89– 100.

Staircase Functions Cumulative Production Cumulative Requirements Inner Corner Conditions 2 n-1 alternatives time

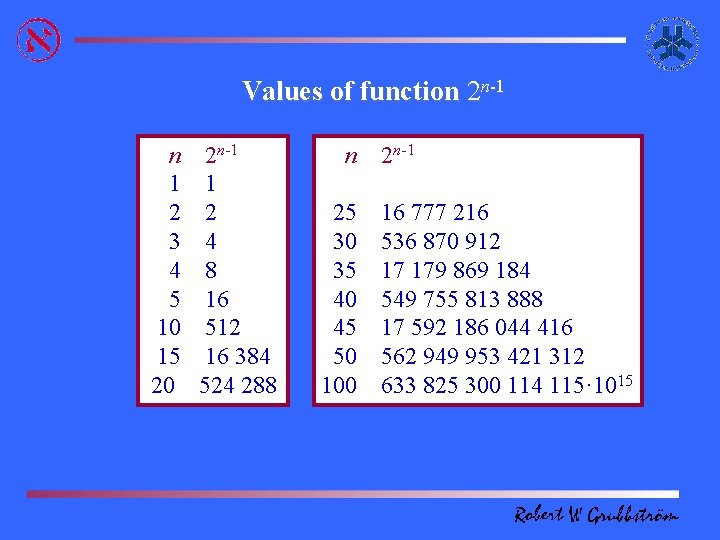

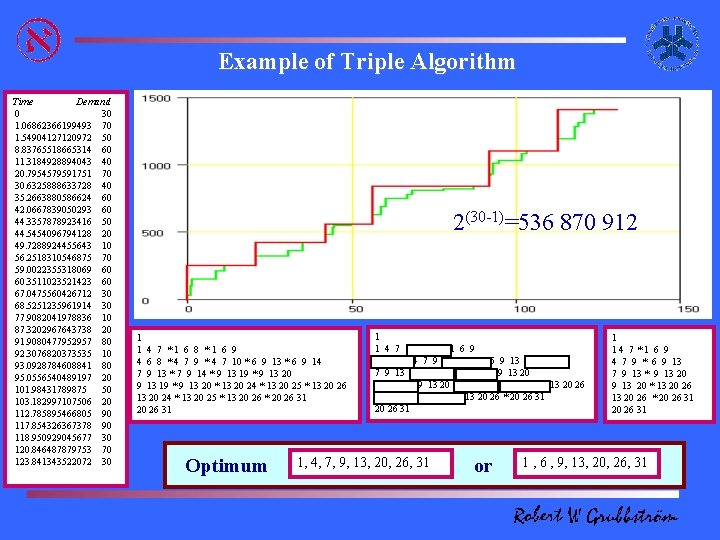

Values of function 2 n-1 n 2 n-1 1 1 2 2 3 4 4 8 5 16 10 512 15 16 384 20 524 288 n 2 n-1 25 16 777 216 30 536 870 912 35 17 179 869 184 40 549 755 813 888 45 17 592 186 044 416 50 562 949 953 421 312 100 633 825 300 114 115· 1015

Complexity issues for general assembly systems are studied in: Grubbström, R. W. , Tang, O. , The space of solution alternatives in the optimal lotsizing problem for general assembly systems applying MRP theory, IJPE, Article in Press, 2010, doi: 10. 1016/j. ijpe. 2011. 012.

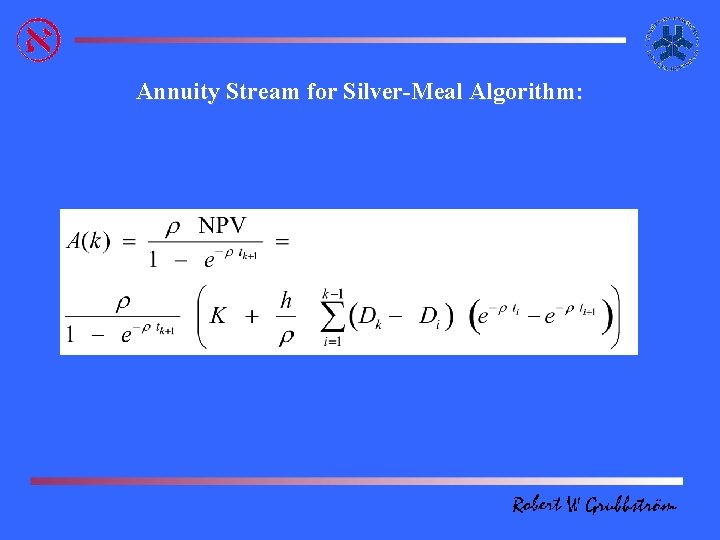

Silver-Meal Algorithm According to the Silver-Meal algorithm the time average of a setup cost and holding costs is computed starting at the time of each replenishment and proceeding in steps of one time unit. As soon as there is an increase in this average cost measure, it is time for a new replenishment. In our terminology, we interpret the average cost expression as the annuity of the out-payments. Therefore, A(k) is computed for k = 2, 3, …. When A(k+1) > A(k), the order at is determined as .

Thomson M. Whitin, b. 1923 Edward A. Silver, b. 1937

Annuity Stream for Silver-Meal Algorithm:

Thomson M. Whitin, b. 1923 Harvey M. Wagner b. 1931 Thomson M. Whitin b. 1923

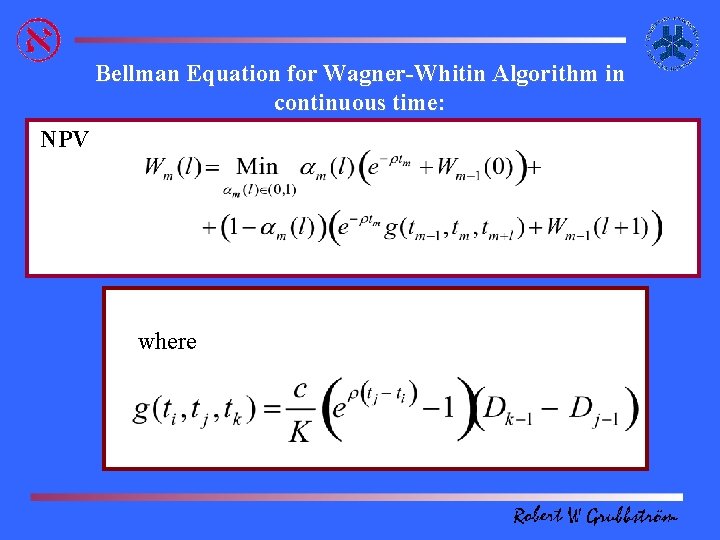

Bellman Equation for Wagner-Whitin Algorithm in continuous time: NPV where

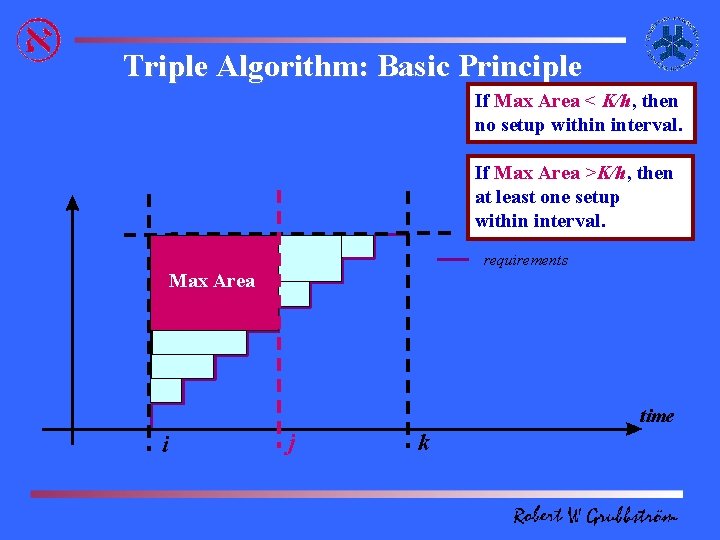

Triple Algorithm: Basic Principle If Max Area < K/h, then no setup within interval. If Max Area >K/h, then at least one setup within interval. requirements Max Area time i j k

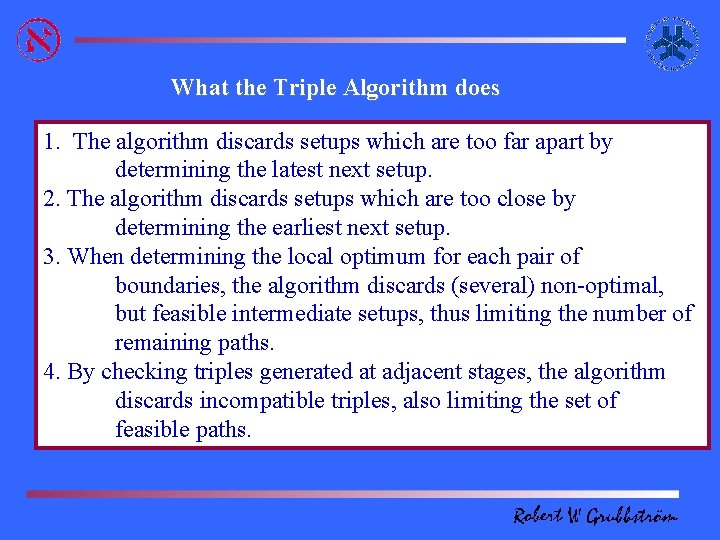

What the Triple Algorithm does 1. The algorithm discards setups which are too far apart by determining the latest next setup. 2. The algorithm discards setups which are too close by determining the earliest next setup. 3. When determining the local optimum for each pair of boundaries, the algorithm discards (several) non-optimal, but feasible intermediate setups, thus limiting the number of remaining paths. 4. By checking triples generated at adjacent stages, the algorithm discards incompatible triples, also limiting the set of feasible paths.

Example of Triple Algorithm Time Demand 0 30 1. 06862366199493 70 1. 54904127120972 50 8. 83765518665314 60 11. 3184928894043 40 20. 7954579591751 70 30. 6325888633728 40 35. 2663880586624 60 42. 0667839050293 60 44. 3357878923416 50 44. 5454096794128 20 49. 7288924455643 10 56. 2518310546875 70 59. 0022355318069 60 60. 3511023521423 60 67. 0475560426712 30 68. 5251235961914 30 77. 9082041978836 10 87. 3202967643738 20 91. 9080477952957 80 92. 3076820373535 10 93. 0928784608841 80 95. 0556540489197 20 101. 98431789875 50 103. 182997107506 20 112. 785895466805 90 117. 854326367378 90 118. 950929045677 30 120. 846487879753 70 123. 841343522072 30 2(30 -1)=536 870 912 1 1 4 7 * 1 6 8 * 1 6 9 4 6 8 * 4 7 9 * 4 7 10 * 6 9 13 * 6 9 14 7 9 13 * 7 9 14 * 9 13 19 * 9 13 20 * 13 20 24 * 13 20 25 * 13 20 26 * 20 26 31 Optimum 1 1 4 7 * 1 6 8 * 1 6 9 4 6 8 * 4 7 9 * 4 7 10 * 6 9 13 * 6 9 14 7 9 13 * 7 9 14 * 9 13 19 * 9 13 20 * 13 20 24 * 13 20 25 * 13 20 26 * 20 26 31 1, 4, 7, 9, 13, 20, 26, 31 or 1 1 4 7 * 1 6 9 4 7 9 * 6 9 13 7 9 13 * 9 13 20 * 13 20 26 * 20 26 31 1 , 6 , 9, 13, 20, 26, 31

MRP Systems

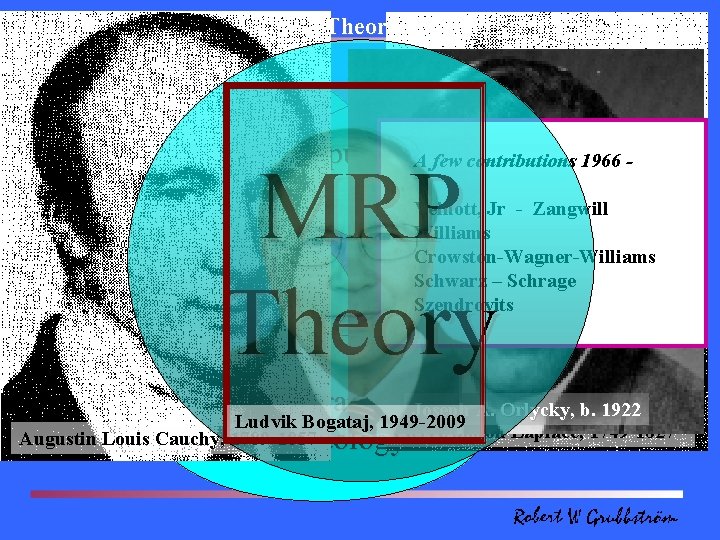

Ingredients of MRP Theory MRP, Input-Output (Activity) A few contributions 1966 CRP, DRP MRP Theory Analysis Veinott, Jr - Multi-Echelon Production- Inventory Systems Andrew 1916 -2004 Wassily Vazsonyi Leontief, , 1906 -1999 Zangwill Williams Crowston-Wagner-Williams Schwarz – Schrage Szendrovits Scientific Programming (Gozinto) Laplace transform Joseph A. Orlycky, b. 1922 Ludvik Bogataj, 1949 -2009 Augustin Louis Cauchy, 1789 -1857 methodology. Pierre Simon Laplace, 1749 -1827

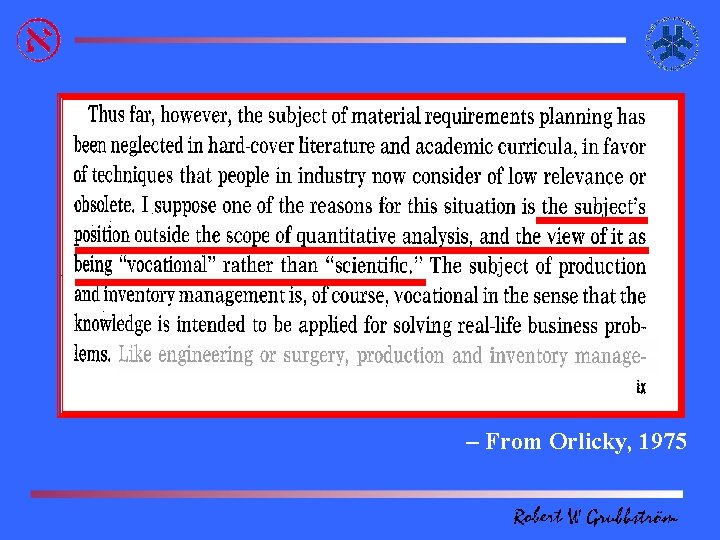

– From Orlicky, 1975

Example illustrating MRP Theory Input Matrix Product Structure Lead Times Lead Time Matrix Generalised Leontief Inverse s = Laplace frequency Robert W. Grubbström

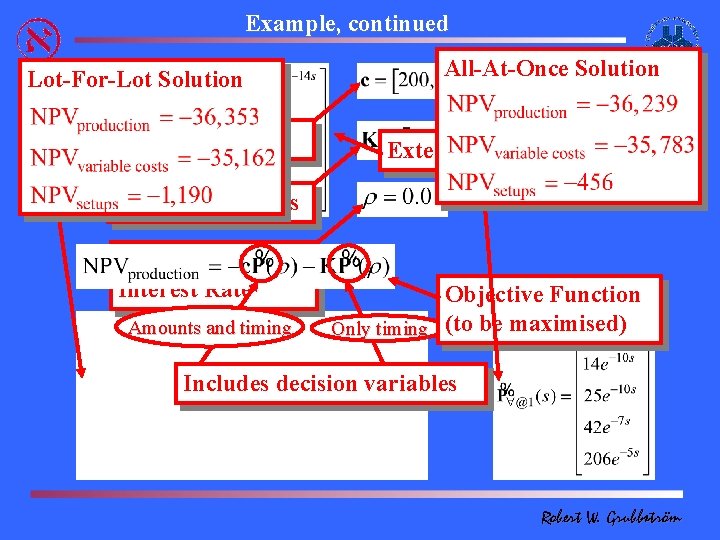

Example, continued Lot-For-Lot Solution Production Costs All-At-Once Solution External Demand Fixed Setup Costs Continuous Interest Rate Amounts and timing Objective Function Only timing (to be maximised) Includes decision variables Robert W. Grubbström

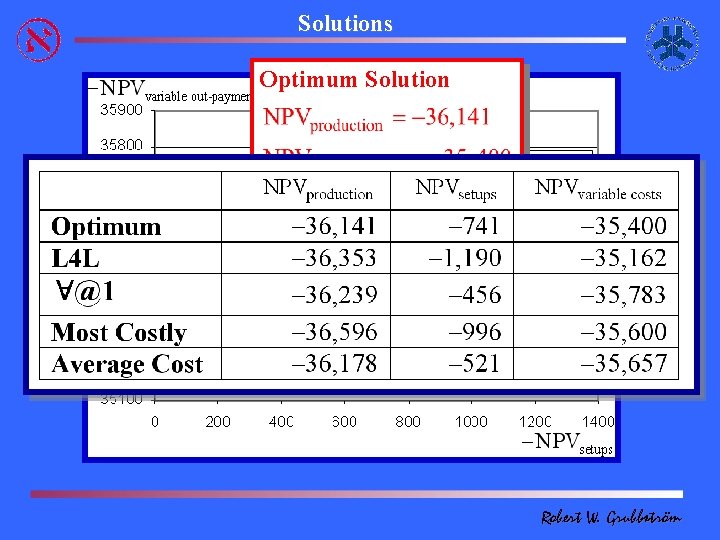

Solutions Optimum Solution Robert W. Grubbström

Recycling

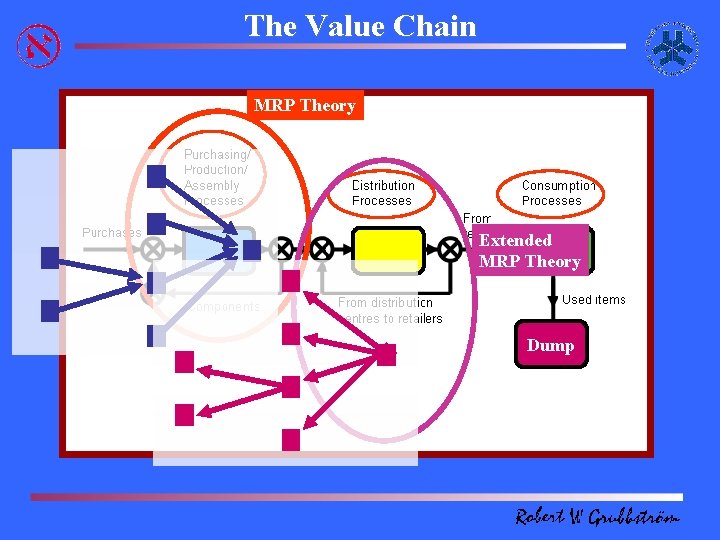

The Value Chain MRP Theory Extended MRP Theory Dump

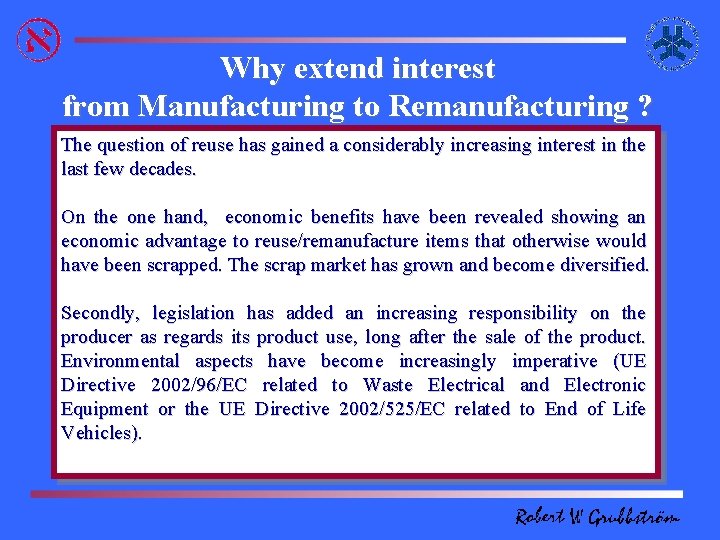

Why extend interest from Manufacturing to Remanufacturing ? The question of reuse has gained a considerably increasing interest in the last few decades. On the one hand, economic benefits have been revealed showing an economic advantage to reuse/remanufacture items that otherwise would have been scrapped. The scrap market has grown and become diversified. Secondly, legislation has added an increasing responsibility on the producer as regards its product use, long after the sale of the product. Environmental aspects have become increasingly imperative (UE Directive 2002/96/EC related to Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment or the UE Directive 2002/525/EC related to End of Life Vehicles).

So what’s the difference between Manufacturing and Remanufacturing ? It turns out that it is not just the question of having more source alternatives available. The new alternatives are shown to have new properties. New properties concern: • product structures, • timing, • material flows (including disposals), • inventory patterns, • financial evaluation (especially holding costs).

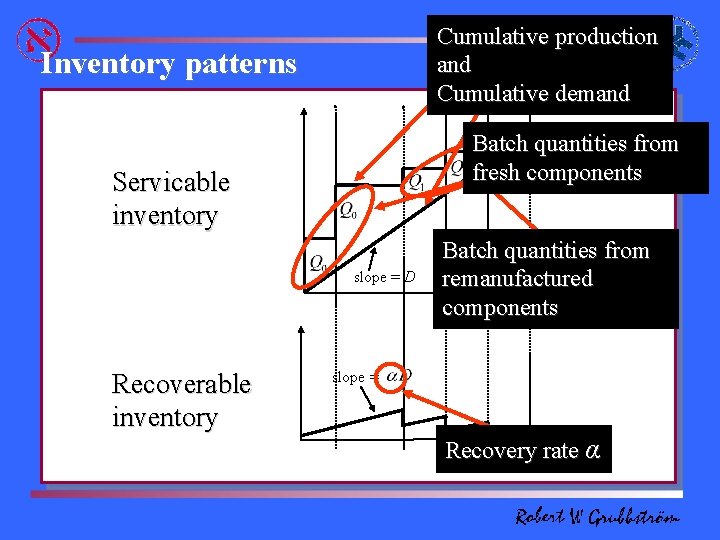

Cumulative production and Cumulative demand Inventory patterns Batch quantities from fresh components Servicable inventory slope = D Recoverable inventory Batch quantities from remanufactured time components slope = time Recovery rate α

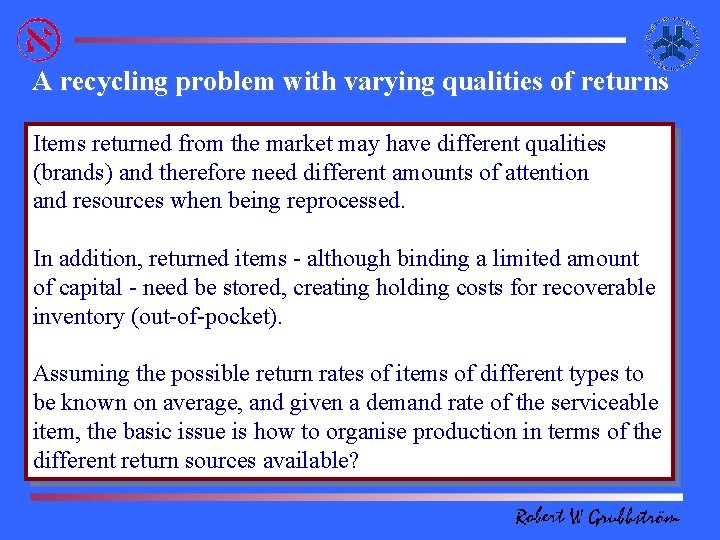

A recycling problem with varying qualities of returns Items returned from the market may have different qualities (brands) and therefore need different amounts of attention and resources when being reprocessed. In addition, returned items - although binding a limited amount of capital - need be stored, creating holding costs for recoverable inventory (out-of-pocket). Assuming the possible return rates of items of different types to be known on average, and given a demand rate of the serviceable item, the basic issue is how to organise production in terms of the different return sources available?

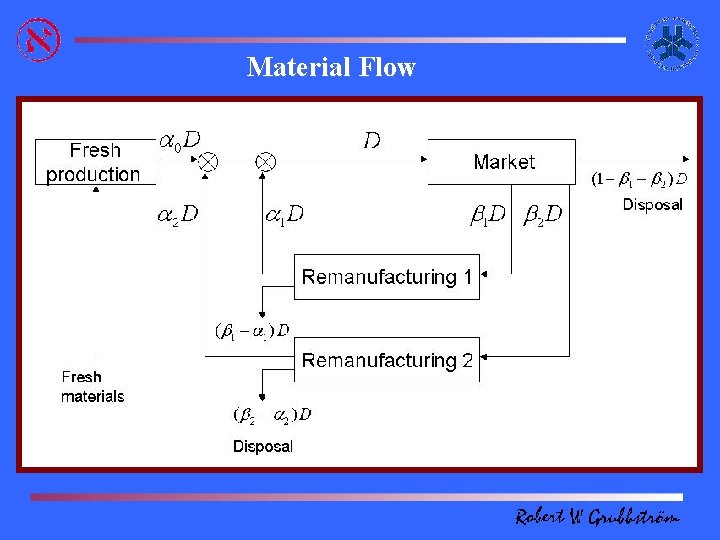

Material Flow

AC Approximation Solution

Balancing Queueing and Capacity Costs

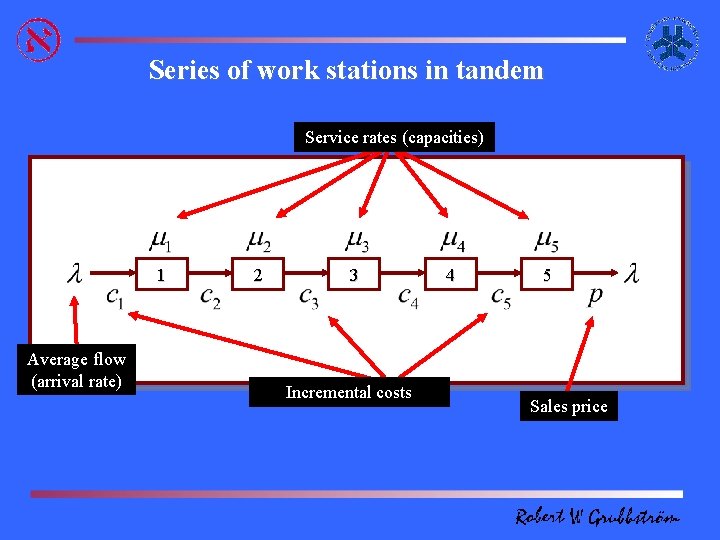

Series of work stations in tandem Service rates (capacities) 1 Average flow (arrival rate) 2 3 Incremental costs 4 5 Sales price

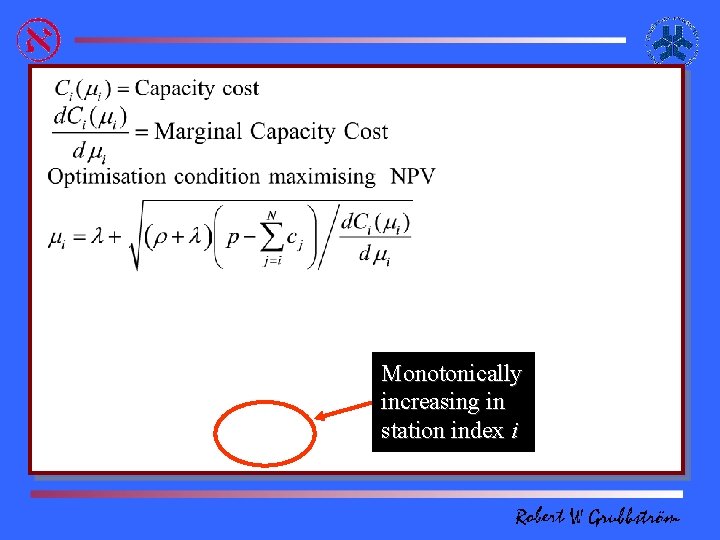

Monotonically increasing in station index i

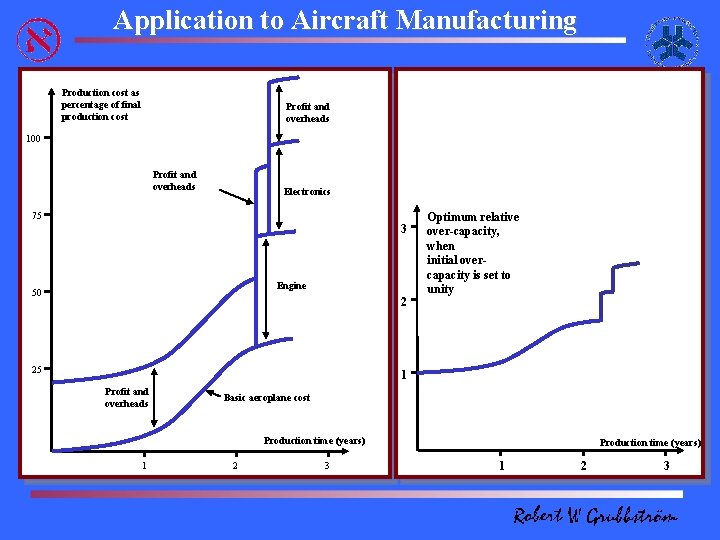

Application to Aircraft Manufacturing Production cost as percentage of final production cost Profit and overheads 100 Profit and overheads Electronics 75 3 Engine 50 2 25 Optimum relative over-capacity, when initial overcapacity is set to unity 1 Profit and overheads Basic aeroplane cost Production time (years) 1 2 3

Conclusions

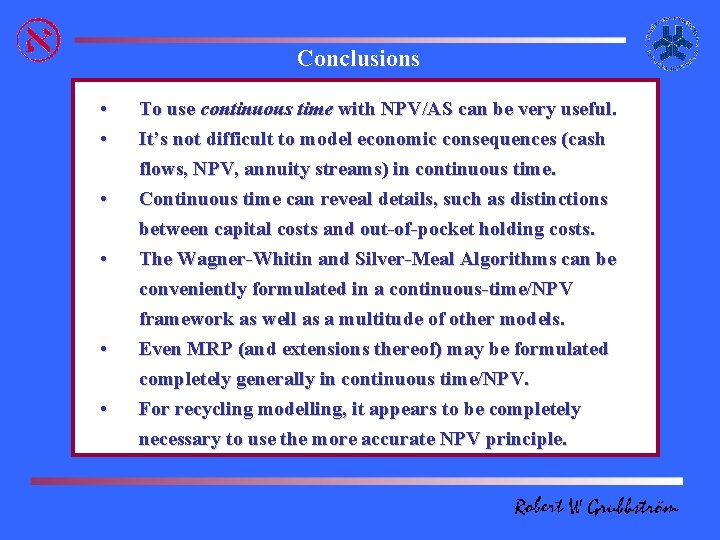

Conclusions • • • To use continuous time with NPV/AS can be very useful. It’s not difficult to model economic consequences (cash flows, NPV, annuity streams) in continuous time. Continuous time can reveal details, such as distinctions between capital costs and out-of-pocket holding costs. The Wagner-Whitin and Silver-Meal Algorithms can be conveniently formulated in a continuous-time/NPV framework as well as a multitude of other models. Even MRP (and extensions thereof) may be formulated completely generally in continuous time/NPV. For recycling modelling, it appears to be completely necessary to use the more accurate NPV principle.

References

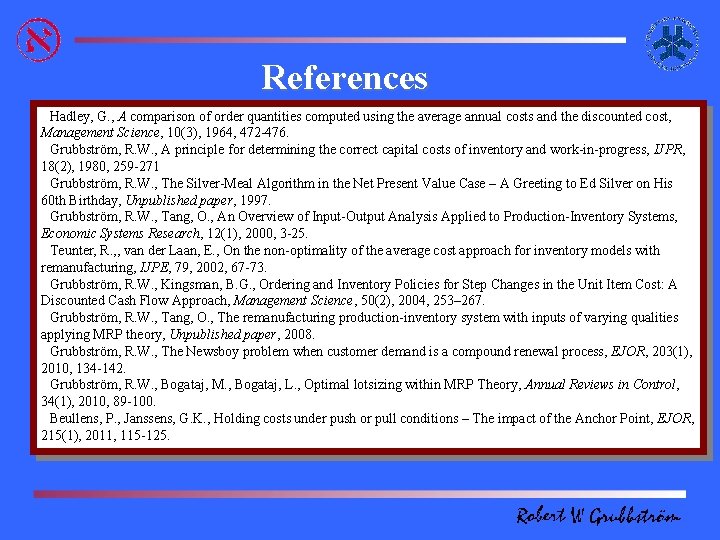

References ØHadley, G. , A comparison of order quantities computed using the average annual costs and the discounted cost, Management Science, 10(3), 1964, 472 -476. ØGrubbström, R. W. , A principle for determining the correct capital costs of inventory and work-in-progress, IJPR, 18(2), 1980, 259 -271 ØGrubbström, R. W. , The Silver-Meal Algorithm in the Net Present Value Case – A Greeting to Ed Silver on His 60 th Birthday, Unpublished paper, 1997. ØGrubbström, R. W. , Tang, O. , An Overview of Input-Output Analysis Applied to Production-Inventory Systems, Economic Systems Research, 12(1), 2000, 3 -25. ØTeunter, R. , , van der Laan, E. , On the non-optimality of the average cost approach for inventory models with remanufacturing, IJPE, 79, 2002, 67 -73. ØGrubbström, R. W. , Kingsman, B. G. , Ordering and Inventory Policies for Step Changes in the Unit Item Cost: A Discounted Cash Flow Approach, Management Science, 50(2), 2004, 253– 267. ØGrubbström, R. W. , Tang, O. , The remanufacturing production-inventory system with inputs of varying qualities applying MRP theory, Unpublished paper, 2008. ØGrubbström, R. W. , The Newsboy problem when customer demand is a compound renewal process, EJOR, 203(1), 2010, 134 -142. ØGrubbström, R. W. , Bogataj, M. , Bogataj, L. , Optimal lotsizing within MRP Theory, Annual Reviews in Control, 34(1), 2010, 89 -100. ØBeullens, P. , Janssens, G. K. , Holding costs under push or pull conditions – The impact of the Anchor Point, EJOR, 215(1), 2011, 115 -125.

Thank you very much for your kind attention Robert W. Grubbström

- Slides: 77