WORDS FORMS MEANING TRANSPARENT OPAQUE One of the

- Slides: 41

WORDS FORMS & MEANING TRANSPARENT & OPAQUE

• One of the assumptions with which linguists have been operating so far and which may now be made explicit is that words have meaning as well as form. • Lyons (1995) stated that one form word may have more than one meaning ( head, chief, leader , start, top) and vice versa , different forms may indicate the same meaning ( happy , cheerful, glad )

• In any language, not only English, which is associated with a writing system, whether alphabetic or non alphabetic, words have both a spoken form and a conventionally accepted written form. • In certain cases, the same spoken language is associated with different writing systems, so that the same spoken word may have several different written forms. • Conversely phonologically distinct spoken languages may be associated, not only with the same writing system, but with the same written language, provided that, as is the case with the so called dialects of Modern Chinese, there is a sufficient degree of grammatical and lexical isomorphism among the different spoken languages

word form meaning written

citing written spoken

inflectional

English, as far as verbs are concerned, there are two alternative conventions. • The more traditional everyday convention, which is less commonly adopted these days by linguists, is the infinitive form, (to + the stem form ): e. g. , to love, to sing, To be, etc. • The less traditional convention, is to use the stem form (or one of the stem forms), e. g. love, sing, be, etc. • In English language , the stem form (or one of the stem forms) is the citation form.

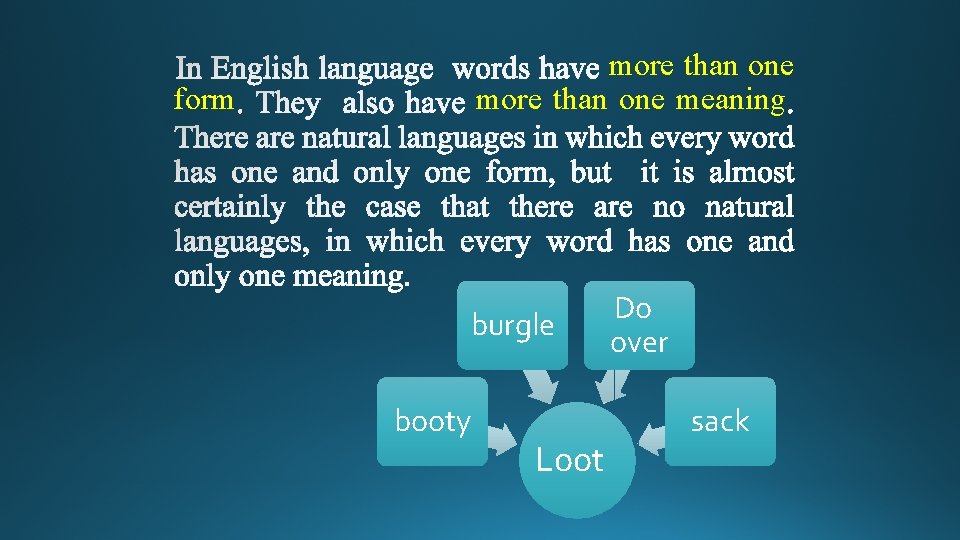

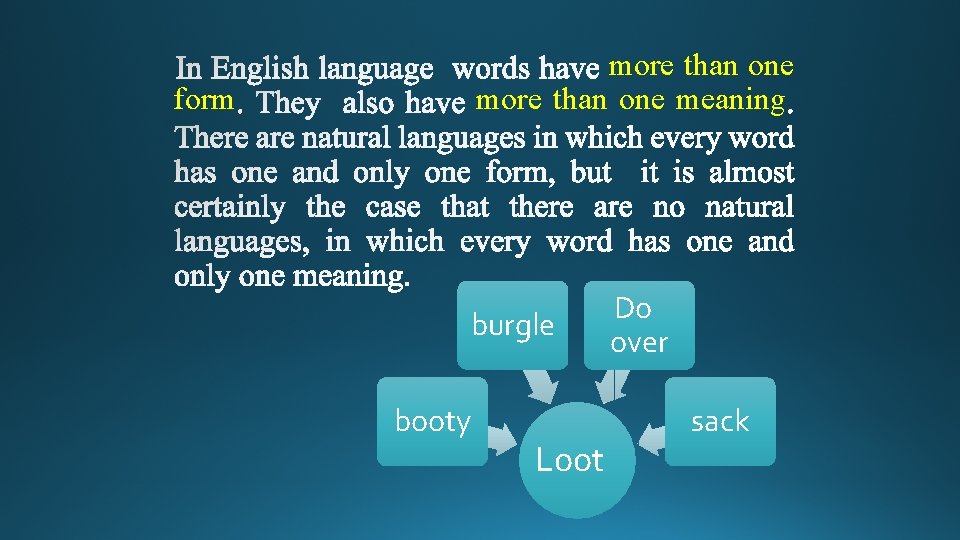

more than one meaning form burgle booty Loot Do over sack

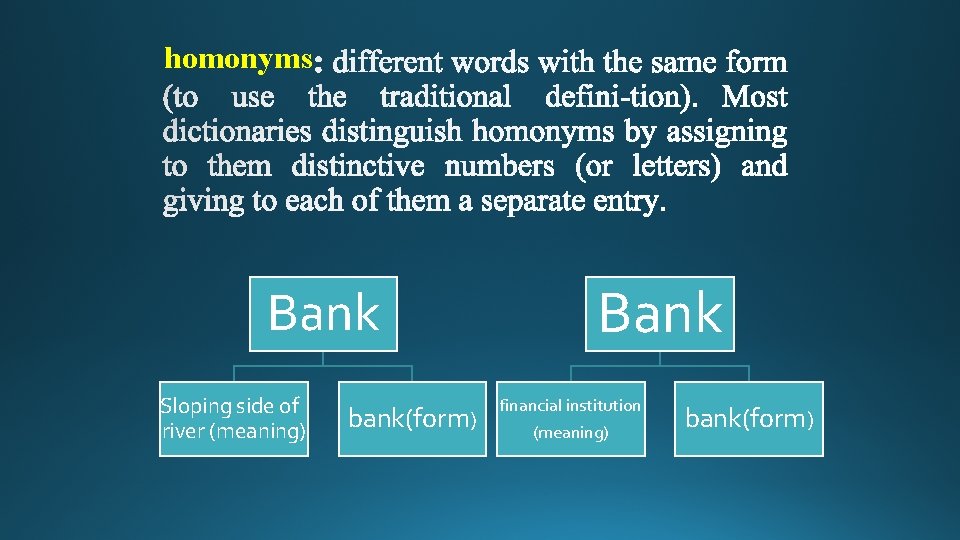

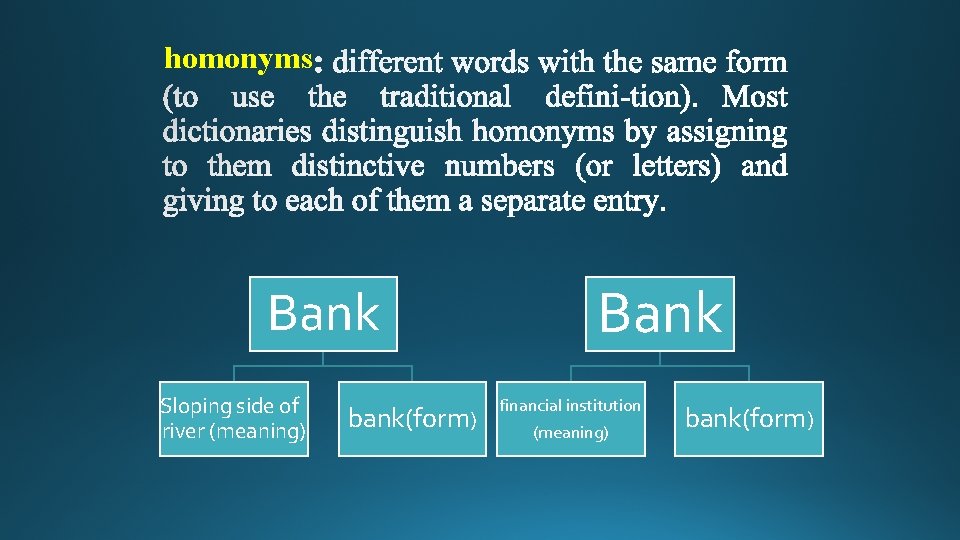

homonyms Bank Sloping side of river (meaning) bank(form) Bank financial institution (meaning) bank(form)

it is taken for granted, for example, that those consulting the dictionary will agree that bank 1 is a different word from bank 2. There are two reasons why bank 1 and bank 2 are traditionally regarded as homonyms. First of all, they differ etymologically: bank 1 was borrowed from Italian (cf. the Modern Italian banca). bank 2 can be traced back through Middle English, and beyond, to a Scandinavian word related ultimately to the German source of the Italian banca but differing from it in its historical development. Sec ond, they are judged to be semantically unrelated: there is assumed to be no connection more precisely, no synchronically obvious connection between the meanings of bank 1 and the meanings of bank 2

Lyons concluded certain the fact: • that there may be a mismatch between the spoken and the written form (or forms) of words; and • that there are different ways in which forms may be identical with one another or not. The use of the term form (and even more so of its deriv ativeformal) in linguistics is at times both confused and confusing. we can now say that two forms are identical if they have the same form. For example, two spoken forms will be phonetically identical if they have the same pronunciation; and two written forms will be orthographically identical if they have the same spelling. A further distinction can be drawn, as far as the spoken language is concerned, between phonetic and phonological identity.

The fact that two (or more) written forms may be phonetically identical is illustrated from English (in many, if not all, dialects): cf. soul and sole, great and grate, or red and read. The fact that two or more phonetically different forms may be orthographically identical is also readily illustrated from English: cf. blessed (in The bishop blessed the congregation vs Blessed are the peacemakers), The kind of identity that has just been discussed and exemplified may be called material identity. it is dependent on the physical medium in which the form is realized. Extensions and refinements of the notion of material identity are possible.

In English, words may have two or more grammatically distinct forms: Man , man‘s, men and men‘s. Typically, as with the four forms of man, the grammatically distinct more specifically, the inflectionally distinct forms of a word are materially different But material identity is neither a sufficient nor a necessary condition of the grammatical identity of forms. For example, the form come serves as one of the present tense forms of come (they come) and also as what is traditionally called its past participle form (they have come). Is come the same form in both cases? The answer is; in one sense, yes; and, in another sense, no. The come of they come is the same as the come of they have come in the sense that it is materially identical with it (in both the spoken and the written language). But the come of they come and the come of they have come are different inflectional forms of the verb come.

TRANSPARENT AND OPAQUE Transparent words are those whose meaning can be determined from the meaning of their parts. Opaque words those for which this is not possible. Thus, chopper and doorman are transparent, but axe and porter are opaque (Ullmann, 1962).

ØThe naturalists ØConventionalists • Rabelais

conventional character conventional motivated opaque transparent motivated

sense connection name

name sense connection

a. Primary acoustic experience b. Secondary movement

affinity elementary

2. Sounds are not expressive in themselves, it is only when they fit the meaning

3.

a word is only onomatopoeic only if it is felt as such evaluation of certain types of onomatopoeia will be a matter of personal opinion

• Morphological Motivation: words are motivated by their morphological structure. preacher is transparent because it can be analyzed into component morphemes which have themselves some meaning: (preach + suffix –er) which forms agent nouns from verbs. • Semantic Motivation: is of two types: a) Metaphoric: motivated by similarity between the garments and the objects referred to(bonnet and hood of a car). b) Metonymic: garments are associated with the person they designate (the cloth for the clergy).

Morphological and Semantic Motivation Morphological and semantic motivation have certain features in common distinguishing them from onomatopoeia: 1. A word is motivated both morphologically and semantically (blue bell). 2. Both kinds are relative: they enable us to analyze words to their elements but not explain these elements themselves (preacher = preach + er) but (preach or er) can’t be further explained. 3. Both involve a subjective element: for a word to be motivated it must be felt to be a compound, derivative, or figurative expression. • the main factors which may influence people’s awareness of words motivation will be clear by considering the ways in which motivation may change.

Two opposite tendencies are at work all the time in the development of language: 1. Many words lose their motivation. This loss is of two kinds: a) Loss of phonetic motivation. b) Loss of morphological and semantic motivation. 2. Others which were, or had grown, opaque become transparent in the course of the history. This is called “acquisition of motivation” and is of two kinds: a) Acquisition of phonetic motivation. b) acquisition of morphological and semantic motivation.

1. Loss of phonetic motivation: The main factor which tends to obscure the phonetic motivation of words is sound change. The best example is the Latin word barbarus which shows how far can a word drift and obscured its onomatopoeic effects: a) By an imitation of the bizarre noises made in an incomprehensible foreign language, but nothing of the original meaning and motivation is left in English brave. b) the learned forms borrowed directly from Latin, such as English barbarous and barbaric have retained some of the expressive force of their ancestry; the effect is not far removed from the original one.

• Loss of morphological transparency may come about in three main ways: a) Phonetic changes may once again play a key role in destroying motivation. The parts of which a compound is made up may coalesce in such a degree that it becomes an opaque, unanalyzable unit (hlafweard=hlaford=lord). b) Compounds and derivatives may also lose their motivation if any of their elements falls into disuse. The days of the week are a case in point. Only Sunday and, perhaps, Monday are fully analyzable in English; the rest have become opaque since the disappearance of the names of pagan divinities on which they were based. c) Even where the elements are alive and phonetically

• morphological and semantic motivation is to some extent a subjective matter. A writer interested in words, sensitive to their nuances and implications, and familiar with their history will be more aware of their derivation than an unsophisticated speaker. He might even attempt, when opportunity offers, to revitalize them by bringing them back to their etymological origins. This can be done either by: a) Explicit comment or b) Implicitly, by placing the word in a context which will suddenly reveal its hidden background. • T. S. Eliot chooses the more subtle technique of contrast effect when trying to restore to the word revision its full etymological value: And time yet for a hundred indecisions, And for a hundred visions and revisions, Before the taking of a toast and tea. The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock

• The sudden sound change, which cancels out the expressiveness of many words, may provide others with new onomatopoeic effects. • The French verbs gemir 'to groan, to moan, to wail' and geindre 'to whine, to whimper' have more onomatopoeic force than the Latin gemere from which they have developed through a series of phonetic and morphological changes.

Popular etymology is one of the best known aspects of semantics, it has four major characteristics: 1. In some cases, the new motivation will affect the meaning of a word but will leave its form intact. For example, the French adjective ouvrable is derived from the old verb ouvrer (Latin operari) 2. Conversely, there are cases where the new motivation will alter the form of a word while the meaning remains unchanged. A well known example is English bridegroom which comes from Old English brydguma. a compound of brýd 'bride' and guma 'man'. When the latter term dis appeared, the second element of the compound became opaque and was subsequently identified with the word groom 'lad'; hence the modern form which goes back to the sixteenth century.

3. Many cases, popular etymology will have an effect both on the form and on the meaning of words. An interesting example is the archaic and dialectal term sand-blind 'half blind, dim sighted, purblind'. This is usually considered to be a de formation of Old English samblind whose first syllable, the prefix sam 'half', became opaque and was wrongly identified with sand. 4. In languages with a non phonetic system of spelling, popular etymology may be confined to the written word without affecting its pronunciation. Thus, English island owes its s to the influence of the historically unconnected isle, and the g in sovereign (from French souverain, Mediaeval Latin superānus) is due to confusion with reign.

• Popular etymology can also furnish semantic motivation for a vague term. When two words are identical in sound and not too dissimilar in meaning, there will be a tendency to regard them as one word with a literal and a transferred sense. • An interesting example in English is ear, name of the organ, and its homonym ear which means a spike or head of corn. The two come from entirely different roots, the former being related to German Ohr and Latin auris, the latter to German Ahre and Latin acus, aceris. Their homonymy in English has led to the invention of a semantic link totally unjustified by history: most people would probably regard ear of corn as a metaphor based on the similarity between the spike and the organ (Bloomfield, Language, p. 436).

• It was one of Saussure's most important discoveries that the proportion of transparent and opaque words varies from one language to another and sometimes from one period to another in the same idiom. • He distinguishes between lexicological languages which have a preference for the conventional word, and grammatical languages. Although the terms ‘lexicological’ and ‘grammatical’ are not very happily chosen, Saussure had the merit of formulating the problem in all its main aspects. • Saussure’ s remarks apply only to morphological motivation. He said that English is less motivated than German.

there are other important effect of motivation which can be demonstrated far more precisely. : 1. The preponderance of the transparent or the opaque type in a given language will have a direct bearing on the treatment of foreign words. In a flexible idiom, rich in compounds and derivatives, purism and linguistic chauvinism will find a more fertile soil than in a language where such resources are sparingly used. 2. Motivation is of direct relevance to the learning and teaching of foreign languages. One could not say in general that transparent idioms are easier to acquire than opaque ones, for the advantages and disadvantages are very neatly balanced; but the methods of study ought to be adapted to the basic design of the language.

3 The contrast between transparent and opaque languages may also have important social and cultural consequences. In English, the presence of countless Greek and Latin words 'inkhorn terms', as they were called in the sixteenth century has helped to build a 'language bar' between those with and without a classical education.

THANK YOU