Word Structure Part 1 The Structure of Words

- Slides: 31

Word Structure Part 1

The Structure of Words: Morphology • Fundamental concepts in how words are composed out of smaller parts • The nature of these parts • The nature of the rules that combine these parts into larger units • What it might mean to be a word

Today I. Morphemes II. Types of Morphemes III. Putting Morphemes together into larger structures – – Words with internal structure Interesting properties of compounds

I. Morphemes • Remember that in phonology the basic distinctive units of sound are phonemes • In morphology, the basic unit is the morpheme • Basic definition: A morpheme is a minimal unit of sound and meaning (this can be modified in various ways; see below)

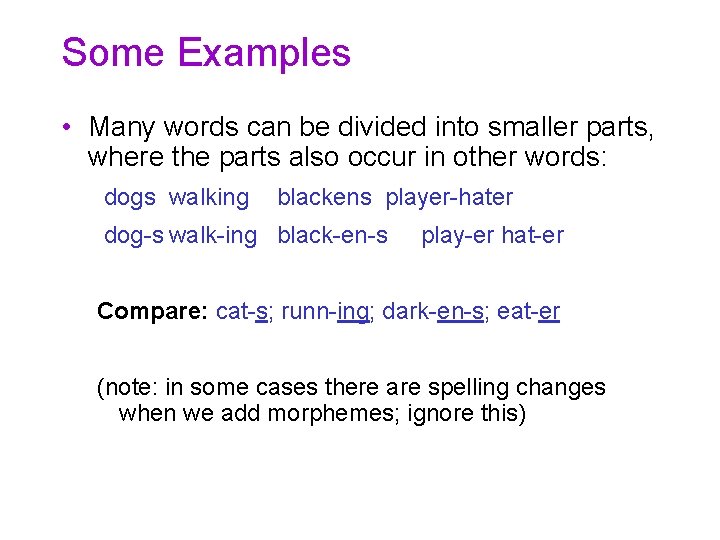

Some Examples • Many words can be divided into smaller parts, where the parts also occur in other words: dogs walking blackens player-hater dog-s walk-ing black-en-s play-er hat-er Compare: cat-s; runn-ing; dark-en-s; eat-er (note: in some cases there are spelling changes when we add morphemes; ignore this)

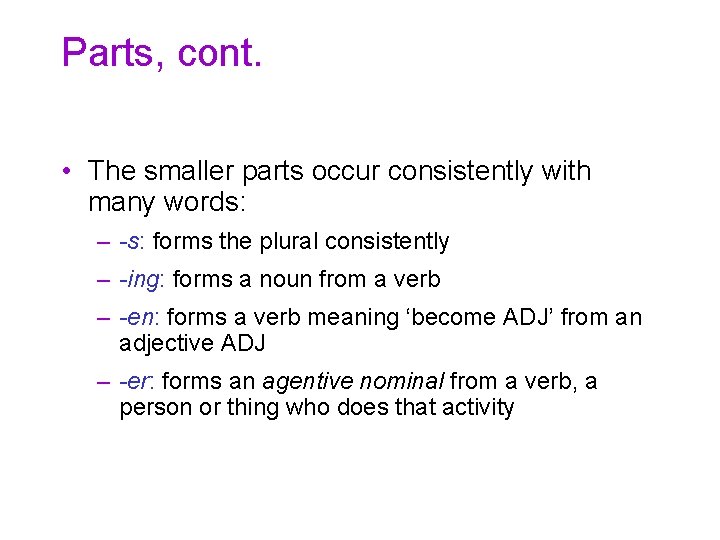

Parts, cont. • The smaller parts occur consistently with many words: – -s: forms the plural consistently – -ing: forms a noun from a verb – -en: forms a verb meaning ‘become ADJ’ from an adjective ADJ – -er: forms an agentive nominal from a verb, a person or thing who does that activity

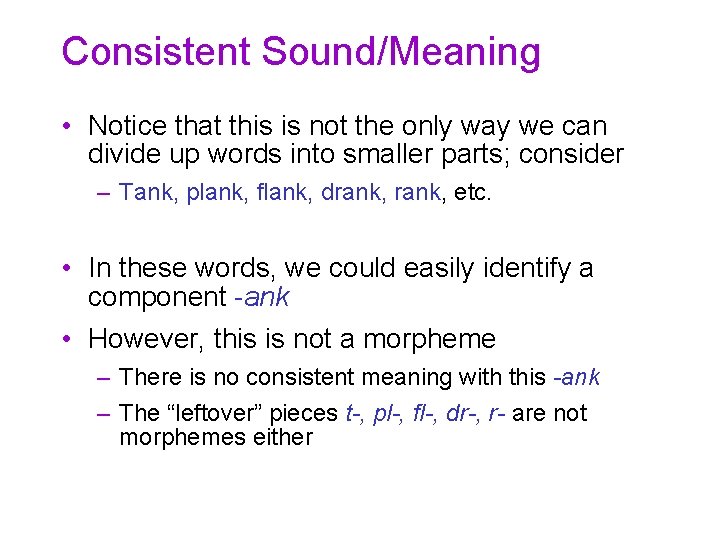

Consistent Sound/Meaning • Notice that this is not the only way we can divide up words into smaller parts; consider – Tank, plank, flank, drank, etc. • In these words, we could easily identify a component -ank • However, this is not a morpheme – There is no consistent meaning with this -ank – The “leftover” pieces t-, pl-, fl-, dr-, r- are not morphemes either

Connections between Sound and Meaning • Remember that a phoneme sometimes has more than one sound form, while being the same abstract unit: /p/ with [p] and [ph] • A related thing happens with morphemes as well • In order to see this, we have to look at slightly more complex cases

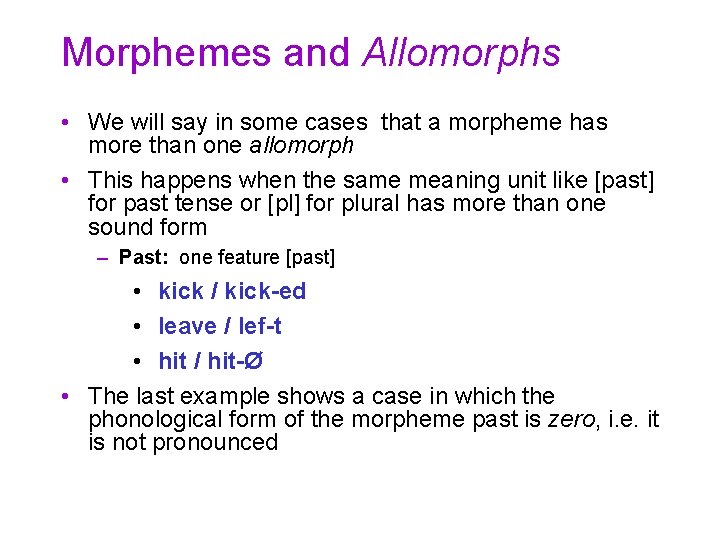

Morphemes and Allomorphs • We will say in some cases that a morpheme has more than one allomorph • This happens when the same meaning unit like [past] for past tense or [pl] for plural has more than one sound form – Past: one feature [past] • kick / kick-ed • leave / lef-t • hit / hit-Ø • The last example shows a case in which the phonological form of the morpheme past is zero, i. e. it is not pronounced

Allomorphy, cont. • In the case of phonology, we said that the different allophones of a phoneme are part of the same phoneme, but are found in particular contexts • The same is true of the different allomorphs of a morpheme • Which allomorph of a morpheme is found depends on its context; in this case, what it is attached to: – Example: consider [pl] for English plural. It normally has the pronunciation –s (i. e. /z/), but • moose / moose- Ø • ox / ox-en • box/*box-en/box-es • So, the special allomorphs depend on the noun

An Additional Point: Regular and Irregular • In the examples above, the different allomorphs have a distinct status. One of them is regular. – This is the default form that appears when speakers are using e. g. new words (one blork, two blorks) – For other allomorphs, speakers simply have to memorize the fact that the allomorph is what it is – Example: It cannot be predicted from other facts that the plural of ox is ox-en – Demonstration: The regular plural is /z/; consider one box, two box-es. • Default cases like the /z/ plural are called regular. Allomorphs that have to be memorized are called irregular. • Irregular allomorphs block regular allomorphs from occurring (ox-en, not *ox-es or *ox-en-s).

Two types • There are in fact two types of allomorphy. Think back to phonology… – The Plural morpheme in English has different sound -forms: dog-s/cat-s/church-es • These are predictable, based on the phonological context – In the case of Past Tense allomorphy, it is not predictable from the phonology which affix appears • We can find verbs with the same (or similar) sound form, but with different allomorphs: break/broke, not stake/*stoke • If you think about this case for a while, though, you will notice some patterns; more on this later

II. Morpheme Types We’ll now set out some further distinctions among morpheme types • Our working definition of morpheme was ‘minimal unit of sound and meaning’ • A further division among morphemes involves whether they can occur on their own or not: – No: -s in dog-s; -ed in kick-ed; cran- in cran-berry – Yes: dog, kick, berry

Some Definitions • Bound Morphemes: Those that cannot appear on their own • Free Morphemes: Those that can appear on their own • In a complex word: – The root or stem is the basic or core morpheme – The things added to this are the affixes – Example: in dark-en the root or stem is dark, while the affix– in this case a suffix– is -en

Further points • In some cases, works will use root and stem in slightly different ways • Affixes are divided into prefixes and suffixes depending on whether they occur before or after the thing they attach to. Infixes-- middle of a word (e. g. fan-f*ing-tastic) • For the most part, prefixes and suffixes are always bound, except for isolated instances

Content and Function Words Another distinction: • Content Morphemes: morphemes that have a referential function that is independent of grammatical structure; e. g. dog, kick, etc. – Sometimes these are called “open-class” because speakers can add to this class at will • Function morphemes: morphemes that are bits of syntactic structure– e. g. prepositions, or morphemes that express grammatical notions like [past] for past tense. – Sometimes called “closed-class” because speakers cannot add to this class

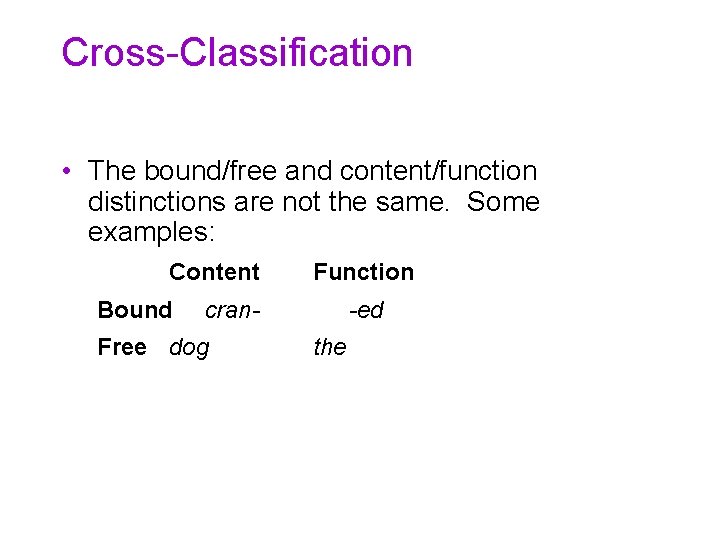

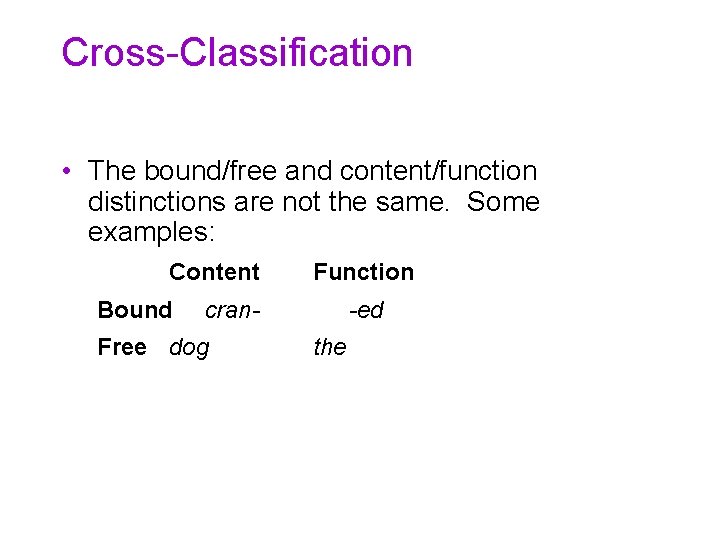

Cross-Classification • The bound/free and content/function distinctions are not the same. Some examples: Content Bound Function cran- Free dog -ed the

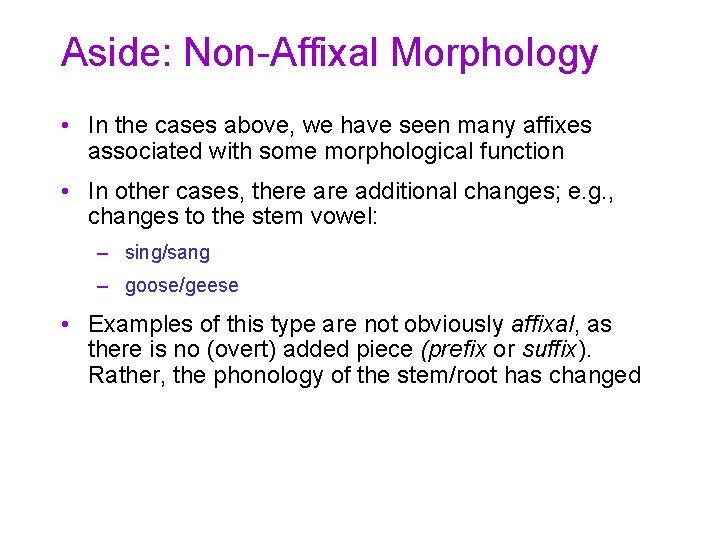

Aside: Non-Affixal Morphology • In the cases above, we have seen many affixes associated with some morphological function • In other cases, there additional changes; e. g. , changes to the stem vowel: – sing/sang – goose/geese • Examples of this type are not obviously affixal, as there is no (overt) added piece (prefix or suffix). Rather, the phonology of the stem/root has changed

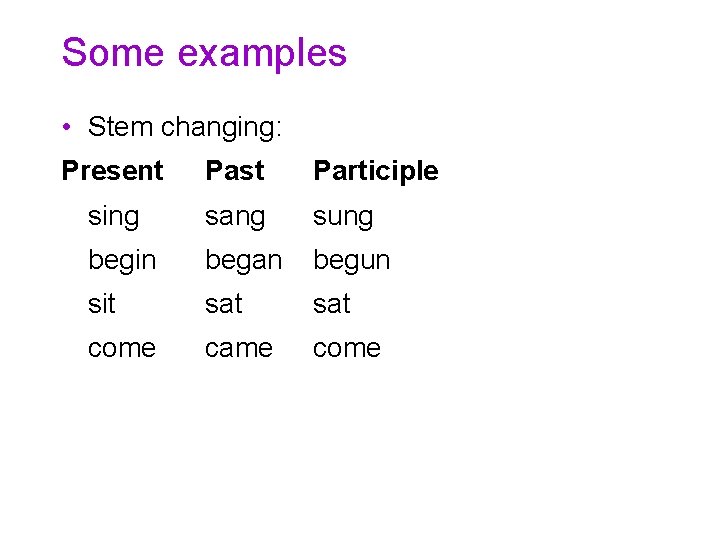

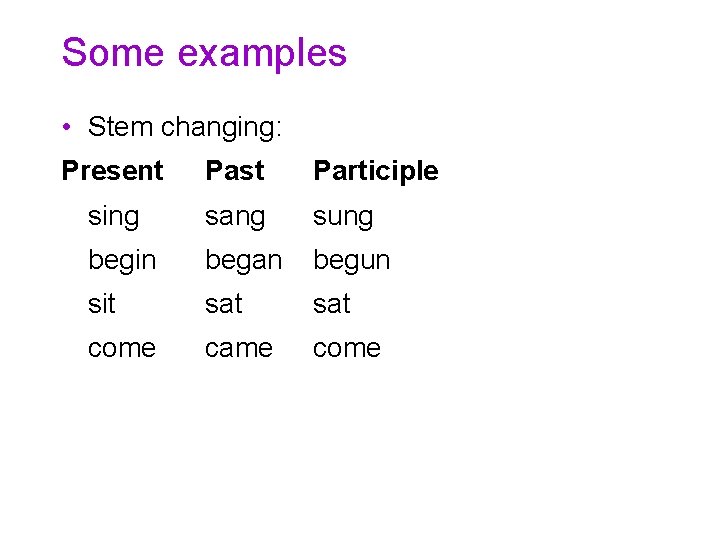

Some examples • Stem changing: Present Past Participle sing sang sung begin began begun sit sat come came come

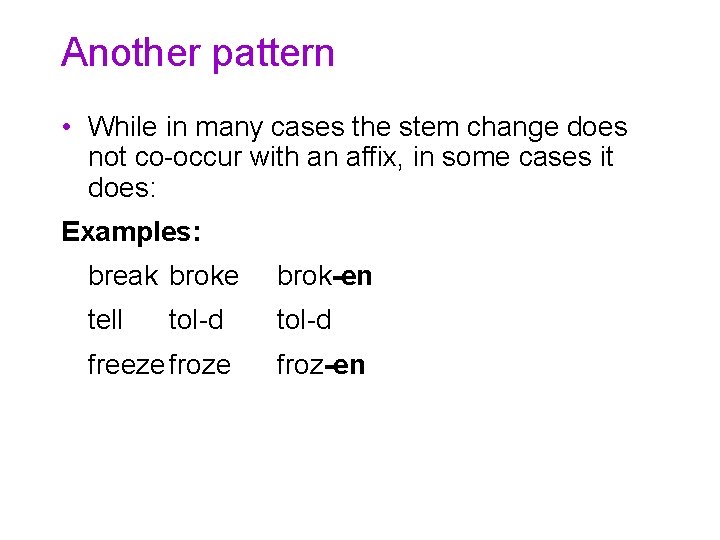

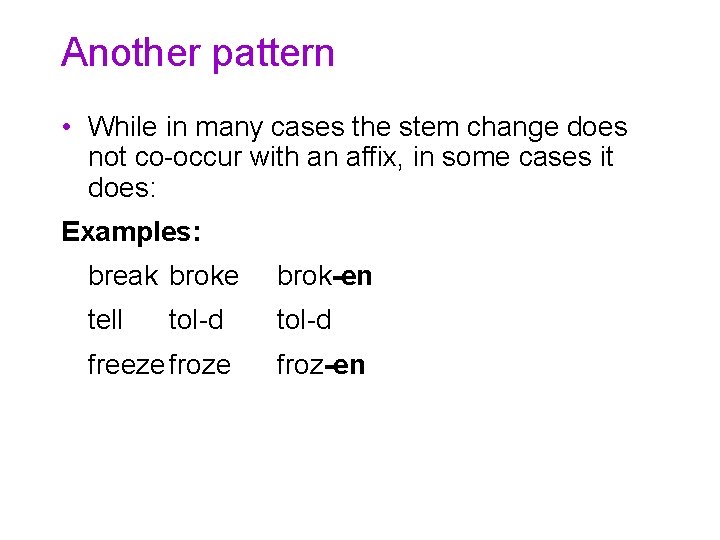

Another pattern • While in many cases the stem change does not co-occur with an affix, in some cases it does: Examples: break broke brok-en tell tol-d freeze froz-en

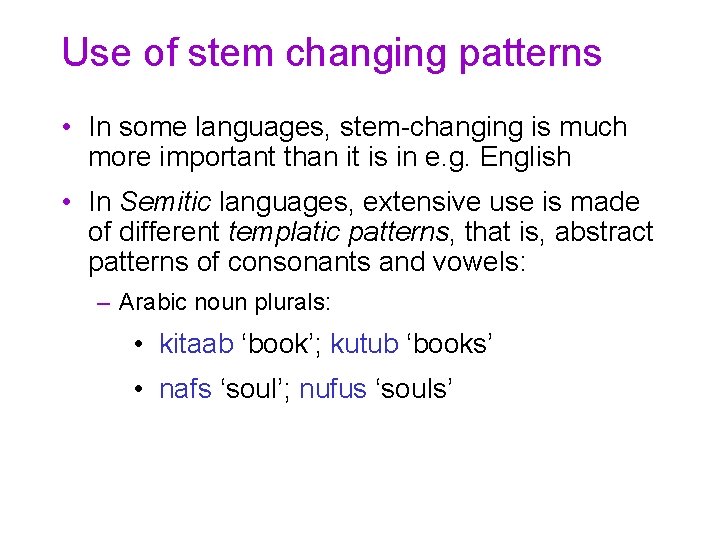

Use of stem changing patterns • In some languages, stem-changing is much more important than it is in e. g. English • In Semitic languages, extensive use is made of different templatic patterns, that is, abstract patterns of consonants and vowels: – Arabic noun plurals: • kitaab ‘book’; kutub ‘books’ • nafs ‘soul’; nufus ‘souls’

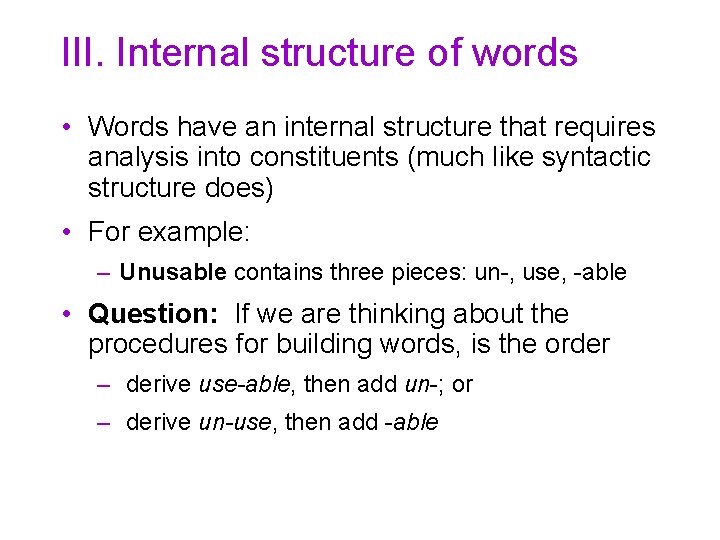

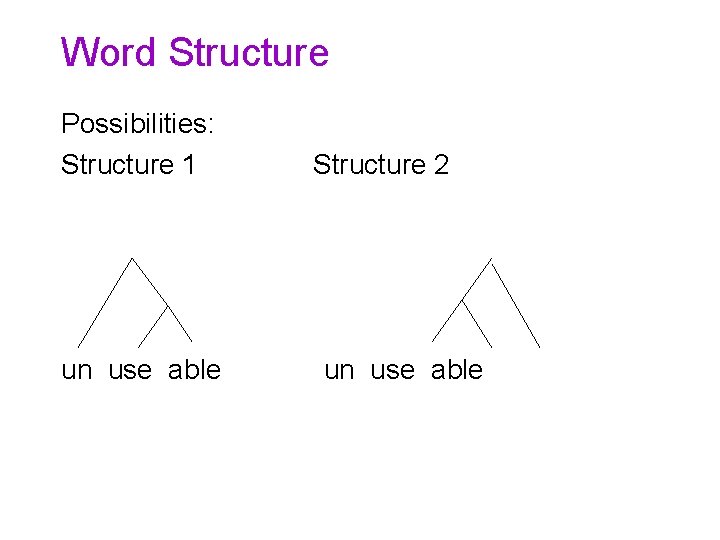

III. Internal structure of words • Words have an internal structure that requires analysis into constituents (much like syntactic structure does) • For example: – Unusable contains three pieces: un-, use, -able • Question: If we are thinking about the procedures for building words, is the order – derive use-able, then add un-; or – derive un-use, then add -able

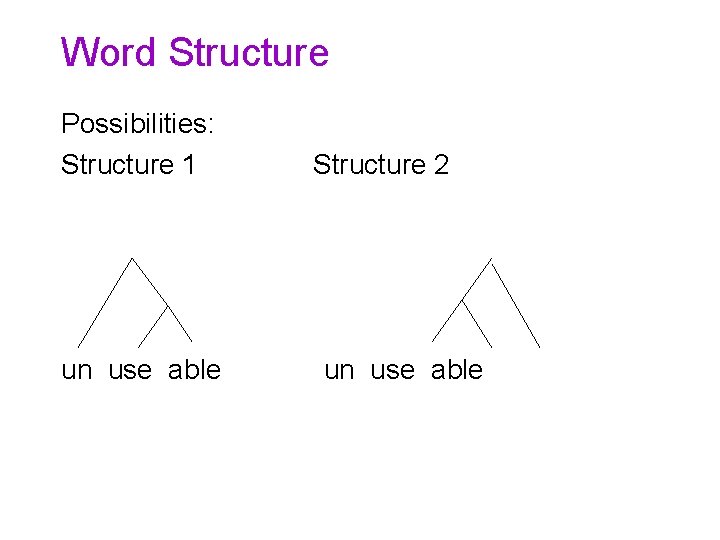

Word Structure Possibilities: Structure 1 un use able Structure 2 un use able

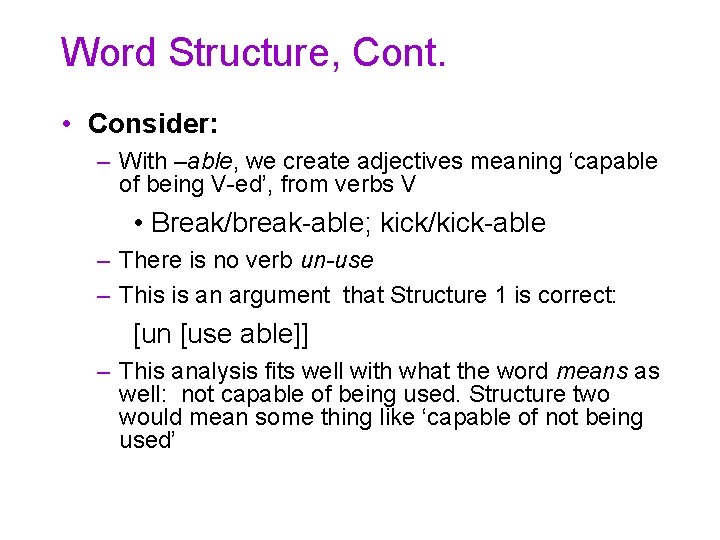

Word Structure, Cont. • Consider: – With –able, we create adjectives meaning ‘capable of being V-ed’, from verbs V • Break/break-able; kick/kick-able – There is no verb un-use – This is an argument that Structure 1 is correct: [un [use able]] – This analysis fits well with what the word means as well: not capable of being used. Structure two would mean some thing like ‘capable of not being used’

Another example • Consider another word (from the first class…): unlockable. Focus on un • Note that in addition to applying to adjectives (clear/unclear) to give a “contrary” meaning, unapplies to some verbs to give a kind of “undoing” or reversing meaning: do, undo zip, unzip tie, untie • Note now that unlockable has two meanings

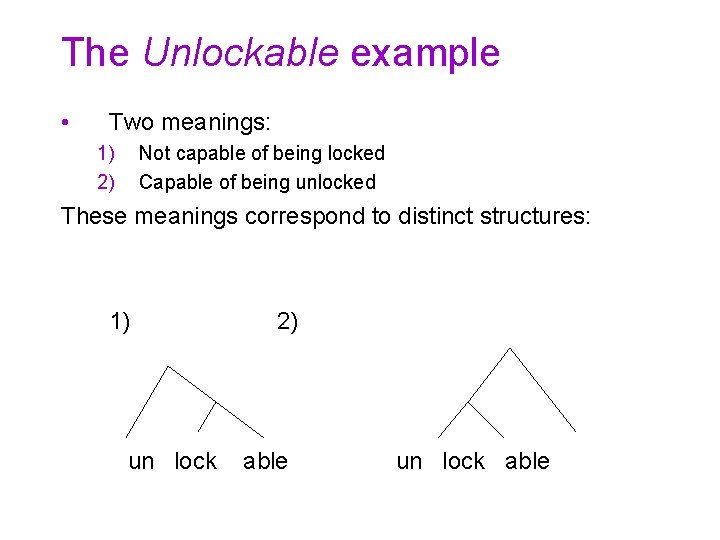

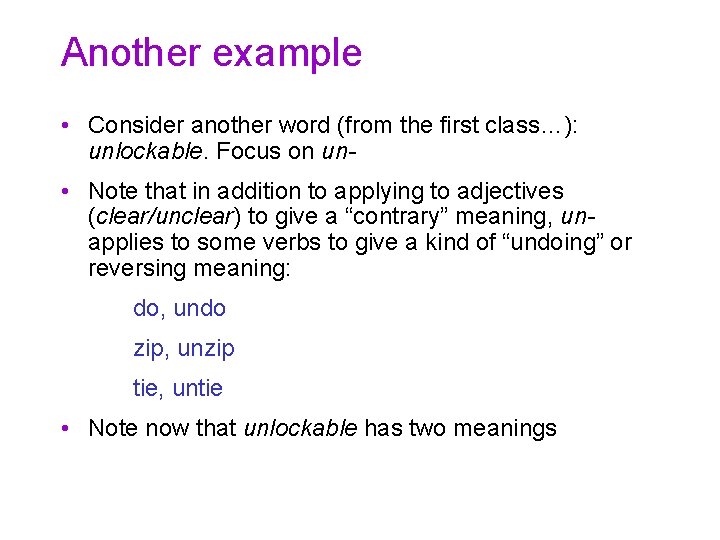

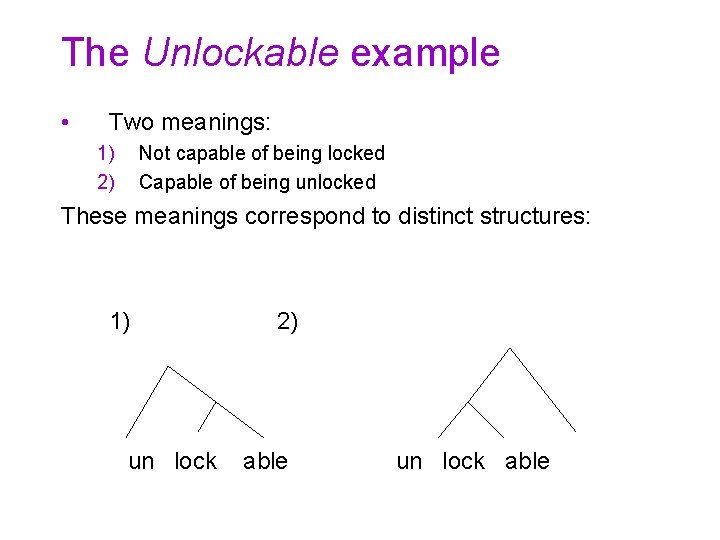

The Unlockable example • Two meanings: 1) 2) Not capable of being locked Capable of being unlocked These meanings correspond to distinct structures: 1) un lock 2) able un lock able

Unlockable, cont. • The second structure is one in which –able applies to the verb unlock • This verb is itself created from un- and lock • The meaning goes with this: ‘capable of being unlocked’ • In structure 1, there is no verb unlock • So the meaning is ‘not capable of being locked’

Some General Points • The system for analyzing words applies in many cases that are created on the fly • Complex words and their meanings are not simply stored; rather, the parts are assembled to create complex meanings • Another example of the same principle applies in the process of compounding

Introduction to Compounding • A compound is a complex word that is formed out of a combination of stems (as opposed to stem + affix) • These function in a certain sense as ‘one word’, and have distinctive phonological patterns • Examples: olive oil shop talk shoe polish truck driver Note that the different elements in these compounds relate to each other in different ways. . .

Internal structure • Like with other complex words, the internal structure of compounds is crucial • There are cases of ambiguities like that with unlockable • Example: obscure document shredder 1) Person who shreds obscure documents [[obscure document] shredder] 2) Obscure person who shreds documents [obscure [document shredder]]

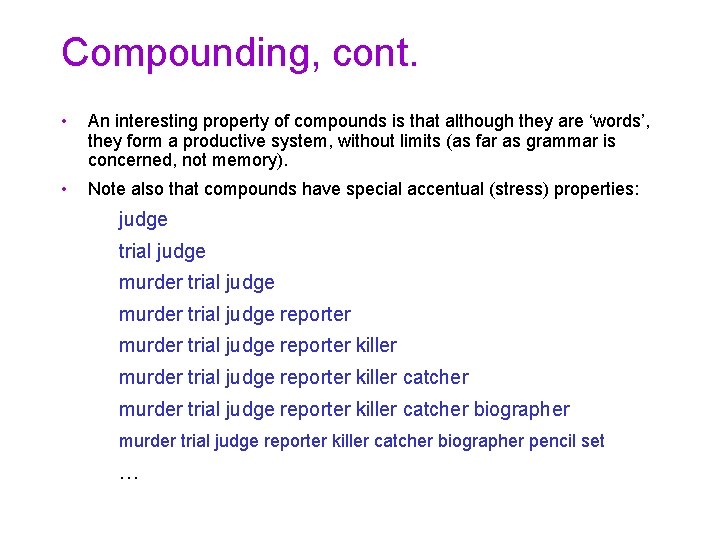

Compounding, cont. • An interesting property of compounds is that although they are ‘words’, they form a productive system, without limits (as far as grammar is concerned, not memory). • Note also that compounds have special accentual (stress) properties: judge trial judge murder trial judge reporter killer catcher murder trial judge reporter killer catcher biographer pencil set …