William Makepeace Thackeray 18071811 24121863 Vanity Fair Contents

- Slides: 18

William Makepeace Thackeray 18/07/1811 -24/12/1863 Vanity Fair

Contents: - William Makepeace Thackeray’s biography - Vanity Fair

William Makepeace Thackeray’s William Makepeace Thackeray was born 18 July 1811, first and only child of biography Richmond Thackeray and Anne Becher Thackeray. He was born in India, where his father worked for the East India Company, and sent to school in England, as was the fashion for colonial-born children, in 1817. His father had died in 1815, and shortly after William left, she remarried to her first love, Captain Henry Carmichael-Smyth. They joined William in England in 1820. Like most English children, William was miserable at school. He wasn't good at sports, though he was fairly popular in spite of that, and suffered through two poor headmasters. He also had his nose broken during a boxing match with another student named George Venables. While in school he developed two habits that were to stay with him all his life: sketching and reading novels. He later attended Cambridge, where he lost a poetry contest to one Alfred Tennyson, though several of William's satirical poems were published around this time. William also met Edward Fitz. Gerald who remained his best friend to the end of his life. William never quite took a degree in anything. He started studying law, though he never actually got anywhere with it. He supported himself by selling sketches and working at a bill discounting firm. He'd fallen in with a bad crowd on the Continent, and he had some rather large gambling debts to pay off. After a brief flirtation with running his own newspaper, William was even more briefly an art student before falling in love with one Isabella Shawe. Since he needed enough money to marry on, William's mother and stepfather, mostly broke due to an economic collapse in India, scraped together all of the funds they could find and started a newspaper called the Constitution. William was appointed the paper's Paris correspondent at £ 450 per year. He'd also had a little book of satirical essays on the ballet published. After a few rocky patches, William and Isabella were married on 20 August 1836.

Their first child, Anne Isabella, was born in June of 1837. Her birth was rapidly followed by the collapse of the Constitution. The sketch market had pretty much dried up, so William began writing as many articles as humanly possible and sending them to any newspaper that would print them. This was a precarious sort of existence which would continue for most of the rest of his life. He was fortunate enough to get two popular series going in two different publications. His personal life, however, wasn't going so well. His second daughter died at less than a year old, and though a third daughter, Harriet Marian, was born in 1840 and thrived, Isabella did not. She fell victim to some sort of mental illness and after a few months was so suicidal and difficult to control that she was placed in a private institution. She remained in one institution or another for the rest of her life and outlived her husband by thirty years. Now William's life got really busy. Over the next few years, he wrote The History of Henry Esmond, The Newcombes, and Vanity Fair, made two lecture tours of America, carried on a protracted flirtation with one Jane Brookfield, wife of an old school friend, and stood as an independent candidate in an Oxford by-election. Through all this, he was continually ill with recurrent kidney infections caused by a bout with syphillis in his youth, but he still managed to have an impressive house built and settle generous dowries on his daughters. In 1859, he and a friend named George Smith started an inexpensive monthly called the Cornhill Magazine, which set a first issue sales record at over 110, 000 copies. William, besides editing, contributed a great series of essays called the Roundabout Papers In 1863, William, who felt his health was now seriously bad, travelled around visiting old haunts and friends to say goodbye. Sure enough, on Christmas Eve, 1863, he died of a cerebral effusion (a burst blood vessel). His funeral drew around 2, 000 mourners, including Dickens. William's recently widowed mother continued to stay with his daughters and was a terrible burden on them until she died in 1864. Minnie, the younger daughter, married Leslie Stephen, had one daughter, and died suddenly at 35. Leslie, besides editing Cornhill, later remarried and had another daughter who became Virginia Woolf.

Vanity Fair - Plot - Concept - Themes - Main Characters

Plot The story opens at Miss Pinkerton's Academy for Young Ladies, where the principal protagonists Becky Sharp and Amelia Sedley have just completed their studies and are preparing to depart for Amelia's house in Russell Square. Becky is portrayed as a strong-willed and cunning young woman determined to make her way in society, and Amelia Sedley is a good natured though simple-minded young girl. However, by the end of the novel, the reader will realize that neither character is unblemished. At Russell Square, Miss Sharp is introduced to Captain George Osborne and to Amelia's brother Joseph Sedley, a clumsy and vainglorious but rich civil-servant fresh from India. Becky entices him and hopes to marry him, though eventually fails as a result of warnings from Captain Osbourne and his own native shyness and embarrassment that Becky had witnessed his foolish behaviour at Vauxhall.

With this Becky Sharp says farewell to Sedley's family and enters the service of the baronet Sir Pitt Crawley who has engaged her as a governess to his daughters. Her behaviour at Sir Pitt's house gains the favour of Sir Pitt, who after the premature death of his second wife, eventually proposes to her. Unfortunately for Becky (who would have gladly consented to becoming the next Lady Crawley) she is already secretly married to his son Rawdon Crawley. Sir Pitt's half sister, the spinster Miss Crawley, is very rich having inherited her mother's fortune of £ 70, 000. Where she will leave her great wealth is a source of constant conflict between the branches of the Crawley family who vie shamelessly for her affections; initially her favourite is Sir Pitt's younger son, Captain Rawdon Crawley. Miss Sharp elopes with him; but this misalliance so enrages Miss Crawley, that she eventually disinherits her nephew in favour of his elder brother. While Becky Sharp is rising in the world, Amelia's father goes bankrupt. Captain George Osborne, persuaded by his friend Dobbin, marries Amelia despite her poverty and his ambitious father's fierce objections. His father wishes him to marry Miss Schwartz, a sugar plantation heiress from the West Indies and a contemporary of Amelia's at Miss Pinkerton's.

When all these personal incidents are going on, the Napoleonic Wars have been gearing up, and George Osborne and William Dobbin are suddenly deployed to Brussels, but not before an encounter with Becky and Captain Crawley at Brighton. The holiday is interrupted with orders to march to Brussels. Already, the newly wedded Osborne is growing tired of Amelia, and he becomes increasingly attracted to Becky. At a ball in Brussels (based on the Duchess of Richmond's ball the night before Waterloo), George gives Becky a note inviting her to run away with him. The morning after, he is sent to Waterloo and dies in the battle. Amelia bears him a posthumous son, who is also named George. With the death of Osborne, Dobbin, who is young George's godfather, gradually begins to express his love for the widowed Amelia, but she is too much in love with George's memory to return his affections. Saddened, he goes to India for many years. Meanwhile, Becky continues her ascent first in post-war Paris and then in London where she is patronised by the great Marquess of Steyne who covertly subsidises her and introduces to London society. Her success is unstoppable despite her iniquitous origins and she eventually meets the Prince Regent himself. At the summit of her success, Becky's unsuitable relationship with the rich and omnipotent Marquess of Steyne is discovered by Rawdon, who leaves his wife and through the offices of Lord Steyne is made Governor of Coventry Island to get him out of England. Mrs Crawley, having lost both husband credibility, is warned by Steyne to quit England she becomes a wanderer on the continent. Wherever she goes, she is stalked by the shadow of Lord Steyne. No sooner has she established herself in some respectable company then one of Steyne's men somehow finds her and spreads rumours of her disreputable history - destroying her. As Amelia's adored son George grows up, his grandfather becomes fond of him and takes him from poor Amelia who knows the rich and bitter old man will give him a much better start in life materially than she or her family could ever manage. Meanwhile both Joseph Sedley and William Dobbin return to England.

Dobbin professes his unchanged love to Amelia, but although Amelia is also affectionate to Dobbin, she tells him she cannot forget the memory of her dead husband. While in England, Dobbin manages a reconciliation between Amelia and her father-in-law. The death of George's grandfather gives Amelia and young George a large fortune. After the death of old Mr Osborne, Amelia, Joseph, George and Dobbin go on a trip to Germany, where they encounter the destitute Becky. Dobbin quarrells with Amelia, and finally realizes that he is wasting his love on a woman too shallow to return it. However, Becky, in a moment of conscience, shows Amelia the note that George (Amelia's dead husband) had given her, asking her to run away with him. This breaks George's idealised image in Amelia's mind, thus eventually bringing Dobbin and Amelia together. Becky resumes her seduction of Joseph Sedley and gains control over him. He eventually dies of a suspicious ailment after signing a portion of his money to Becky as life insurance. In the original illustrations, which were done by Thackeray, Becky is shown behind a curtain with a phial (presumably of poison) in her hand; the picture is labelled 'Becky's second appearance in the character of Clytemnestra. ' (She had played Clytemnestra during charades at a party earlier in the book. ) His death appears to have made her fortune. By a twist of fate Rawdon Crawley dies weeks before his elder brother whose son has already died. Thus the baronetcy descends to Rawdon's son. Had he outlived his brother by even a day he would have become Sir Rawdon Crawley and Becky would have become Lady Crawley - the title she uses regardless in later life. The reader is informed at the end that although Dobbin married Amelia, and always treated her with great kindness, he never fully regained the love that he had once had for her.

Until the publication of Vanity Fair, Thackeray was known as humorous writer; he wrote regularly for Punch. Thackeray regarded humour as doing more than making readers laugh, ‘the best humour is that which contains most humanity, that which is favoured throughout with tenderness and kindness. ’ He was compelled to write the truth about what he saw and how he understood what he saw: To describe it otherwise than it seems to me would be falsehood in that calling in which it has pleased heaven to place me; treason to that conscience which says that men are weak; that truth must e told; that faults must be owned; that pardon must be prayed for; and that love reigns supreme over all. Concept

There may be wishful thinking in his statement that as the writer ‘finds, and speaks, and feels the truth best, we regard him, esteem him -sometimes love him. ’ In order to tell the truth, the novelist must ‘convey as strongly as possible the sentiment of reality. ’ Language should identify exactly, not elevate or exaggerate; for instance, a poker was just that- a poker, not a great red-hot instrument and a coat was only a coat, not an embroidered tunic. He dislikes Dickens’s emotional outbursts and vivid personification of objects; Thackeray protested that the very trees in Dickens’s novels ‘ squint, shiver, leer, grin and smoke pipes. ’ A realist, Thackeray consistently deflated the heroic and sentimental in life and in literature. Thackeray saw the writer as serving a necessary function- to raise the consciousness of his readers. Concerned, he asked his mother in a letter, ‘Who is conscious? ’ He came to himself as a Satirical- Moralist, with a responsibility both to amuse and to teach, ‘A few years ago I should have sneered at the idea of setting up as a teacher at all… but I have got to believe in the business, and in my other things since them. And our profession seems to me as serious as the Parson’s own. ’ He aimed not only to expose the false values and practices of society and its instruments and to portray the selfish, callous behaviour of individuals, but also to affirm the value of truth, justice and kindness. This double aim is reflected in his description of himself as satiric and kind: ‘under the mask satirical there walks about a sentimental gentleman who means not unkindly to any mortal person. ’ Though Thackeray set his novel a generation earlier, he was really writing about his own society (he even used contemporary clothing in his illustrations for the novel). Thackeray saw how capitalism and imperialism with their emphasis on wealth, material goods, and ostentation had corrupted society and how the inherited social order and institutions, including the aristocracy, the church, the military, and the foreign service, regarded own family, rank, power, and appearance. These values morally crippled and emotionally bankrupted every social class from servants through middle classes to the aristocracy.

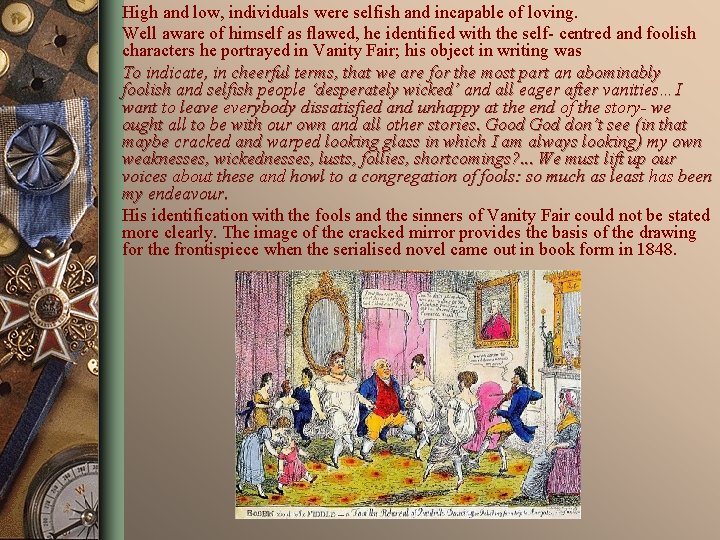

High and low, individuals were selfish and incapable of loving. Well aware of himself as flawed, he identified with the self- centred and foolish characters he portrayed in Vanity Fair; his object in writing was To indicate, in cheerful terms, that we are for the most part an abominably foolish and selfish people ‘desperately wicked’ and all eager after vanities…I want to leave everybody dissatisfied and unhappy at the end of the story- we ought all to be with our own and all other stories. Good God don’t see (in that maybe cracked and warped looking glass in which I am always looking) my own weaknesses, wickednesses, lusts, follies, shortcomings? . . . We must lift up our voices about these and howl to a congregation of fools: so much as least has been my endeavour. His identification with the fools and the sinners of Vanity Fair could not be stated more clearly. The image of the cracked mirror provides the basis of the drawing for the frontispiece when the serialised novel came out in book form in 1848.

Themes Vanity- Vanity, which takes a variety of forms, is a major motivation of individuals and characterises society. Consider the following definitions of vanity: ‘Vain and unprofitable conduct or employment of time’; ‘The quality of being fooling or of holding erroneous opinions’; ‘The quality of being personally vain; high opinion of oneself; self-conceit and desire for admiration. ’ Another meaning of vanity could possibly be the vanity mirror; this meaning relates to the use of mirrors in the text and the drawings. Society’s values- Individuals and society are driven by the worship of wealth, rank, power, and class and are corrupted by them. Consequences of this worship are: 1) the perversion of love, friendship, and hospitability and 2) the inability to love

Selfishness- Everyone is selfish in varying degrees. As little Georgy ironically writes in an essay. ‘An undue love of Self leads to the most monstrous crime and occasions the greatest misfortunes both in States and Families’. The selfishness of characters like Becky, Jos Sedley, and Lord Steyne is obvious; however, even apparently selfless characters like Amelia, Dobbin, and Lady Jane are selfish. Illusion and reality- Motivated by self-interest, the characters practise hypocrisy, they misrepresent themselves both to others and to themselves, and they lie. Some characters deliberately choose their illusions over the truth. Thus, every character deludes others and/or is self-deluded. Heroism- Men and women are not heroic; the heroic poses and pretences of characters, literature and society are consistently deflated. Fiction versus reality- The false portrayal of human nature and activities in novels, romance and literary conventions is distinguished from real life. The subtitle, A Novel Without a Hero; Hero Thackeray’s identifying various characters as the hero or heroine; the marriages of Amelia and Becky early in the novel- all violate novelistic conventions. George Osborne parodies the conventional hero. Married and parental relationships- In a novel of domestic life, there are no happy marriages because of the egotism, selfishness, folly, and false values of individuals and of society. Similarly, selfishness, vanity, snobbery and/or materialism affect every child-parent relationship. The gentleman- Thackeray rejects the older concept of a gentleman as a man of rank and leisure, i. e. member of gentry or aristocracy. The true gentleman, as well as the true lady, is recognised by moral character, being considerate, benevolent and diligent. Amelia, Lady Jane and Dobbin are among the few real ladies and gentlemen in this novel. Time- Thackeray’s concern with time has caused him to be called the novelist of memory. The action is set in the past, and the narrator compares and contrasts the past with the present as he moves between them; occasionally he tells us a future event or outcome. The characters’ memories of the past help to characterise them in the present. Thackeray shows the effect which the passage of time has on the characters. The concern with time is reflected in the structure; the narrator occasionally interrupts the chronology, jumps back in time, and returns to the point where he stopped the chronology.

Main Characters - Society - The hero - Character development

Society Like Austen in Emma, Thackeray identifies the place or status characters have in society and the nature of their relationship to society in Vanity Fair. Unlike Austen, who portrays the limited world of Highbury, Thackeray fills his novel with people, places, and travel. Almost all his characters are individualized, no matter how briefly they appear. We know their attitudes, their values, their hypocrisies and pettiness, their class, their desires and feelings. Taken together they make up the society that Thackeray calls Vanity Fair. His characters also satirize the institutions they serve or represent: Lord Steyne and Sir Pitt Crawley (both the father and the son) show up Parliament, the rotten election system, and the aristocracy; religion is satirized with the Rev. Bute Crawley (the Church of England) and Mr. Pitt Crawley and Lady Southdown (Dissent); the army leadership is satirized with General Tufto; the Colonial and foreign service, with Joseph Sedley, Rawdon Crawley, Mr. Pitt Crawley, and Tapeworm; the financial system, with Osborne senior. One class, however, is excluded, the poor.

Amelia The question of whether the novel has a heroine is more complex. Amelia seems to be the conventional heroine–sweet, passive, self-sacrificing, gentle, tender, and loving. And Thackeray calls her a heroine–at times, but he contradicts himself at other times and says she is not a heroine (he also refers to Becky as a heroine and not a heroine). In addition, he repeatedly calls Amelia "weak" and "selfish. " Of Dobbin's faithful love and decades-long submission to her, Thackeray wrote to a friend that finally "he will find her not worth having. " Thackeray wrote his mother that My object is not to make a perfect character or anything like it. Don't you see how odious all the people are in the book (with the exception of Dobbin)–behind whom all there lies a dark moral I hope. What I want is to make a set of people living without God in the world (only that is a cant phrase) greedy pompous mean perfectly self-satisfied for the most part and at ease about their superior virtue Becky has much more appeal than Amelia for most readers, as Thackeray acknowledged: The famous little Becky Puppet has been pronounced to be uncommonly flexible in the joints, and lively on the wire; the Amelia Doll, though it has had a smaller circle of admirers, has yet been carved and dressed with the greatest care by the artist. . . (x). Born with no advantages, in a society that values rank and wealth, Becky makes her way to the highest levels of society through her own resources, with determination, intelligence, hard work, and talent. She is resourceful and bounces back from every reversal. At the same time, her behaviour and character are morally indefensible; she constantly manipulates others, she lies, she cheats, she steals, she betrays Amelia, and perhaps she even commits a murder. As the novel progresses, some readers feel that she becomes more dangerous and villainous.

Dyson explains Becky's appeal in terms of the corrupt nature of society and her role in that society: . . surely we do admire Becky, and legitimately, however glad we are to be outside the range of her wiles? The fact is that she belongs to Vanity Fair, both as its true reflection, and as its victim; for both of which reasons, she very resoundingly serves it right. Like Jonson's Volpone, she is a fitting scourge for the world which created her–fitting aesthetically, in the way of poetic justice, and fittingly moral, in that much of her evil is effective only against those who share her taint. Dobbins is largely immune to her, since he is neither a trifler, a hypocrite nor a snob. The other characters are all vulnerable in one or other of these ways, and we notice that those who judge her most harshly are frequently the ones who have least earned such a right. A question arises about Becky's innocence in the last portion of the novel. Specifically, is she innocent of adultery? and/or of murder? Thackeray offers a variety of opinions from self-interested and self-righteous observers, who range from the servants to the highest levels of fashionable society; the narrator's opinion remains ambiguous. It is important to keep in mind that though what characters say about one another is significant, their judgments may reveal more about the speaker or society's values than about the person being discussed; the opinion offered may not be trustworthy. Character Development Edwin Muir describes Thackeray's presentation of his characters as a gradual "unfolding in a continuously widening present"; the characters have the same weaknesses, vanities and foibles throughout, the only change being "our knowledge of them. " them

Vanity of vanities, all is vanity

Vanity of vanities, all is vanity Vanity of vanities, all is vanity

Vanity of vanities, all is vanity Vanity fair storyline

Vanity fair storyline Idols of the heart and vanity fair

Idols of the heart and vanity fair Logbook example science fair

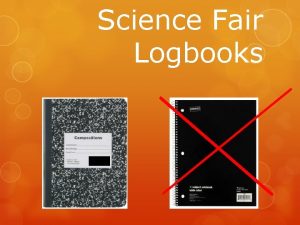

Logbook example science fair Logbook science fair

Logbook science fair Science fair logbook setup

Science fair logbook setup Rhetorical devices syntax

Rhetorical devices syntax Foul is fair and fair is foul literary device

Foul is fair and fair is foul literary device Play significa

Play significa Macbeth stylistic devices

Macbeth stylistic devices Examples of fair is foul and foul is fair in macbeth

Examples of fair is foul and foul is fair in macbeth Fair is foul and foul is fair

Fair is foul and foul is fair Shakespearean sonnet 14 lines examples

Shakespearean sonnet 14 lines examples Intellectual vanity

Intellectual vanity Appeal to vanity example

Appeal to vanity example Love is a fallacy logical fallacies

Love is a fallacy logical fallacies Example of appeal to force

Example of appeal to force Sanity and vanity

Sanity and vanity