Why to Randomize a Randomized Controlled Trial and

- Slides: 24

Why to Randomize a Randomized Controlled Trial? (and how to do it) John Matthews University of Newcastle upon Tyne

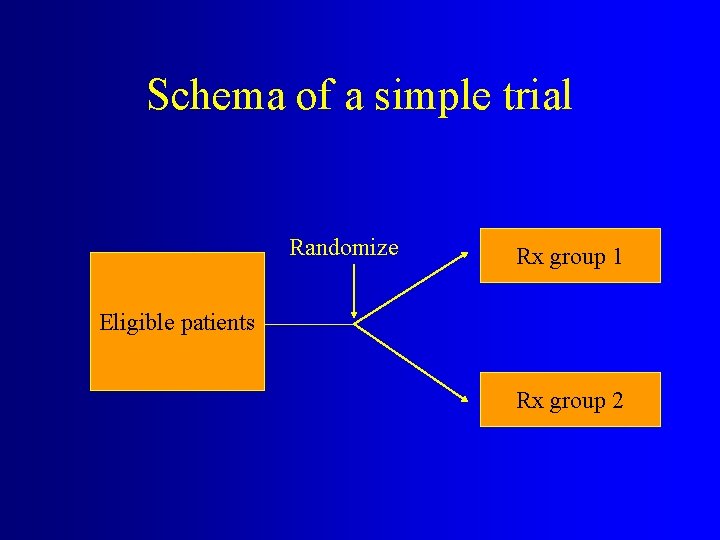

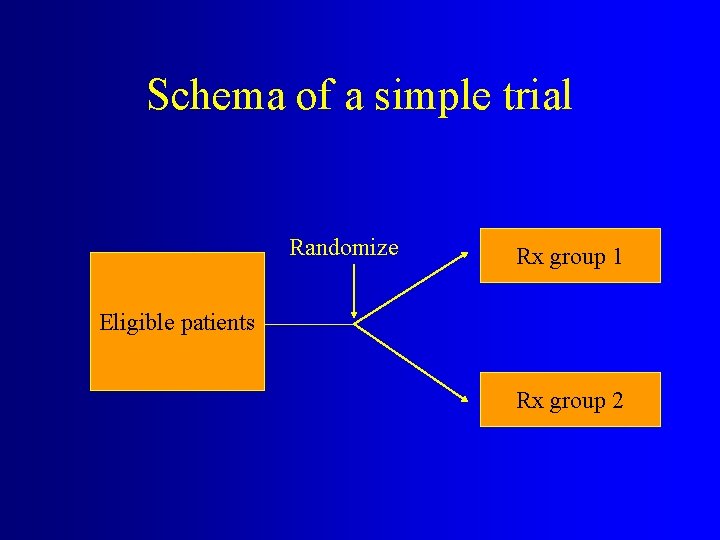

Schema of a simple trial Randomize Rx group 1 Eligible patients Rx group 2

Outline of talk • Many aspects to a trial: this talk focuses on just two • Why you should randomize – benefits of doing so – dangers of failing to do so • How to randomize – often glossed over & unspecified

Why Randomize? • • Compare groups at the end of the trial Difference is because of the Rx For this you need comparable groups Purpose of randomization is to make the treatment groups comparable • Ensures that only difference in groups is due to trial treatments

How does it do it? • Each group is a random sample of eligible patients, so both are representative of that same population • In this sense they are comparable – same proportions of males, stage IV tumours, ambulant cases, elderly patients etc. • Anything which subsequently changes the groups will destroy this balance.

Why Randomize? • Other benefits are – Randomization is largely unpredictable • Why this is a good thing and why it might not obtain will emerge in the talk – Randomization provides a valid basis for statistical inference • This is important but is not addressed at all in this talk

What is wrong with nonrandomized studies? • Two main types of study, those with and those without concurrent control groups

Non-randomized studies II • Without concurrent controls – Uncontrolled • cannot really make much of such studies if there is any variation in outcomes. – Historical controls • type of patient may change, due to eligibility criteria • environment changes, due to trial • data quality often quite different between groups

Non-randomized studies III • Non-randomized concurrent controls – Alternation – Odd/Even hospital no. or date of birth – First letter of surname • Difficult to argue that one group is different from another but allocation is predictable, so bias can arise from selection of patients: see Keirse (1988) – so randomization must be unpredictable

Features of a RCT • Provide reliable evidence of Rx efficacy • Essentially simple • Much attendant methodology – ensure reliability of evidence – give credibility to results • CONSORT statements www. consort-statement. org indicate good practice in trial reporting

How to Randomize • • Toss a coin Essentially the right thing to do Try not to do it in front of the patient More sophisticated implementations possible

Is coin tossing OK? • OK for big trials • For small trials, such ‘simple randomization’ can lead to imbalance in group sizes

Example: trial with 30 patients • If 30 patients are in a trial randomized using coin tossing there is a 14% chance of 15: 15 split • For 16: 14 chance is 27% • ‘Worse’ than 20: 10 is 10% • Why ‘worse’? • Because imbalance leads to loss of power

Alternatives • Could use a restricted randomization scheme – legitimate, intended to protect power – but often not mentioned in trial report: see Altman & Doré, 1990; Schulz et al. , 1994 • Needs to be done properly • Only ensures similar numbers in groups • Combine with stratification to ensure comparability for prognostic factors

Random Permuted Blocks • An allocation sequence is, e. g. , A, B, A, A, B, B, B, A i. e. 6 As, 4 Bs • This sequence built up by using a computer to ‘toss a coin’ • Random Permuted Blocks (RPBs) is an alternative method which ensures imbalance can never be substantial

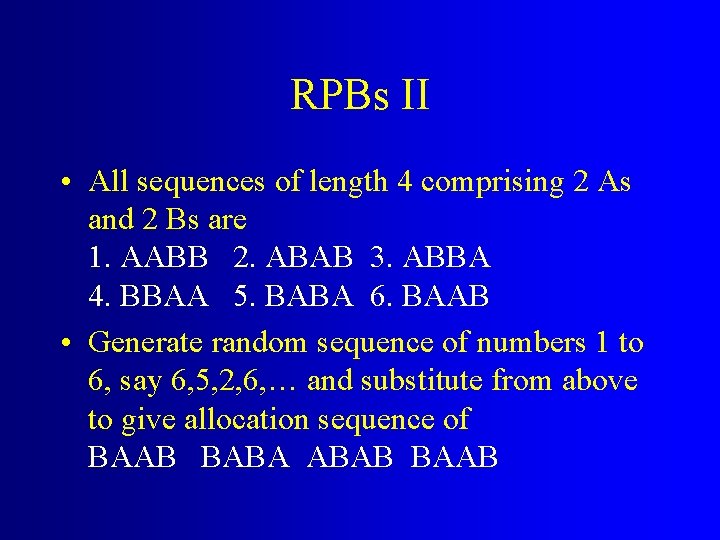

RPBs II • All sequences of length 4 comprising 2 As and 2 Bs are 1. AABB 2. ABAB 3. ABBA 4. BBAA 5. BABA 6. BAAB • Generate random sequence of numbers 1 to 6, say 6, 5, 2, 6, … and substitute from above to give allocation sequence of BAAB BABA ABAB BAAB

RPBs III • Such sequences cannot be more than two out of balance • Must be in exact balance after 4, 8, 12, etc. patients have been recruited • So RPBs are, to some extent, predictable • To avoid this, vary block length at random: use blocks of length six (3 t) as well as 4 (2 t)

Is it enough to equalise numbers? • No, can still have imbalance in important prognostic factors – E. g. two groups of size 15: one comprises 14 young children and the other comprises 14 adolescents in a trial for diabetes • Stratify recruitment with respect to age – i. e. use separate allocation sequence within each stratum

Stratification • RPBs can be used without stratification • Stratification without using RPB (or an equivalent device) is nonsensical • Separate allocation sequence in each stratum can become cumbersome with many prognostic factors • e. g. ambulant/not, over/under 55, M/F gives 8 allocation sequences

Minimisation • More complicated, in principle • ensures balance on each factor separately, not for all combinations • keeps track of patients already in trial, computes an imbalance score and allocates to minimise this • can include a random element • Less cumbersome, in practice • largely because you need a computer • Good if there are many prognostic factors

How to serve it all up • Methods for delivering randomisation sequences to the clinic are important. • They hold the key to ensuring adequate concealment of the allocation until the patient has been randomized.

Implementation methods • Need to separate the person who generates allocation from those who assess eligibility • Third party schemes • Telephone randomization service • Pharmacy randomization • Web-based service? • Envelopes • Serially numbered, sealed and opaque

Then what? • You will have two groups that are comparable and free from bias • Well, sort of • You have the best start, certainly • Drop-outs, protocol violations etc. disturb the comparability • Might not have been comparable to start with! • Need to allow for baseline imbalance and stratifying variables

Conclusion • Randomization is needed in all clinical trials • As with most aspects of trial design, the details of how you randomize are important • The analysis needs to respect the design (esp. stratification) and make sensible adjustment for baselines • All looking more awkward if there isn’t a statistician involved. • Some details given at www. mas. ncl. ac. uk/~njnsm/talks/titles. htm