Why study policy and policy processes Why study

- Slides: 20

Why study policy and policy processes?

Why study policy and policy processes? “In implementing a new paradigm, foresters will not be accorded the luxury of passive observation” – John C. Gordon (JOF, July 1994) “The challenge is to help citizens make sense of the confusing array of facts, falsehoods, metaphors, unknowns, and value statements, and to understand the consequences of policy options. ” David Cleaves (JOF, March 1994)

Why study policy and policy processes? As a natural resource professional, your life is entwined with policy. You may be: • An implementer of policy because it is your job to do it (like it or not!). • A developer/promoter of policy because you know what you want, what to do about it, and you can and do contribute toward attaining it. • A victim (possible!) of policy because you did not know about it, or chose not to do anything about it.

Chapter 2: Policy and Political Processes Text: Cubbage et al. , 1992

Why study policy and policy processes?

Four approaches to studying forest/ natural resource policy 1. Historical 2. Institutional 3. Process or Analysis 4. Integrated (Processes, Participants, & Programs) – current approach

Objectives of forest (nat. res. ) policy • General Aim: assure all actions contribute to socially desirable ends/goals • Hierarchy of goals: Some goals are means to attain other goals – Primal social goal: society’s survival – Examples of other social goals leading to it: • food/shelter/clothing • sustained economic stability & growth, employment • environmental protection

Four types of conflicts among forest policy objectives 1. physical impossibility 2. economic conflict 3. value conflicts 4. time perspectives

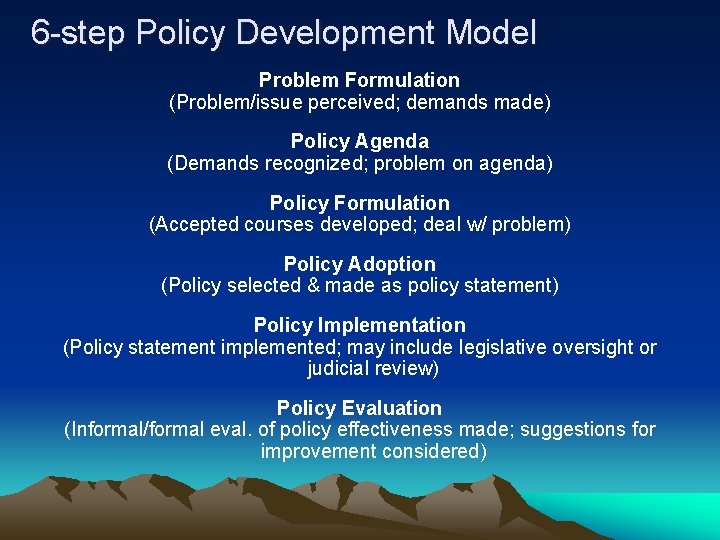

Six steps in policy development (Anderson’s model) 1. problem formulation 2. policy agenda 3. policy formulation 4. policy adoption 5. policy implementation 6. policy evaluation

6 -step Policy Development Model Problem Formulation (Problem/issue perceived; demands made) Policy Agenda (Demands recognized; problem on agenda) Policy Formulation (Accepted courses developed; deal w/ problem) Policy Adoption (Policy selected & made as policy statement) Policy Implementation (Policy statement implemented; may include legislative oversight or judicial review) Policy Evaluation (Informal/formal eval. of policy effectiveness made; suggestions for improvement considered)

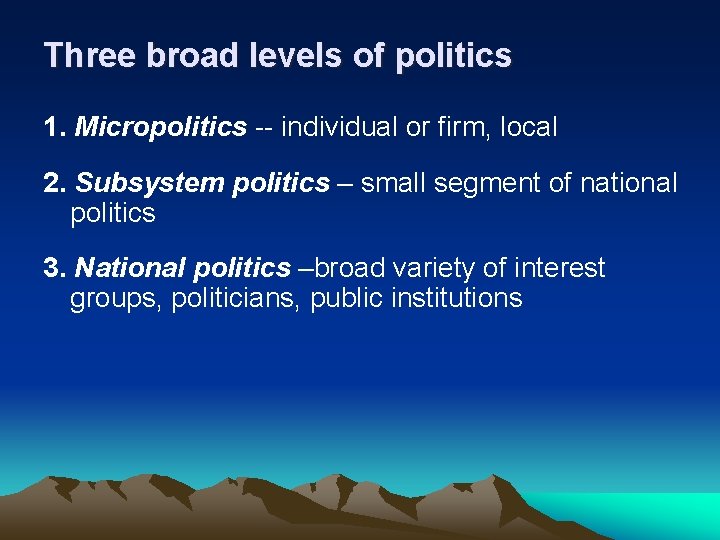

Three broad levels of politics 1. Micropolitics -- individual or firm, local 2. Subsystem politics – small segment of national politics 3. National politics –broad variety of interest groups, politicians, public institutions

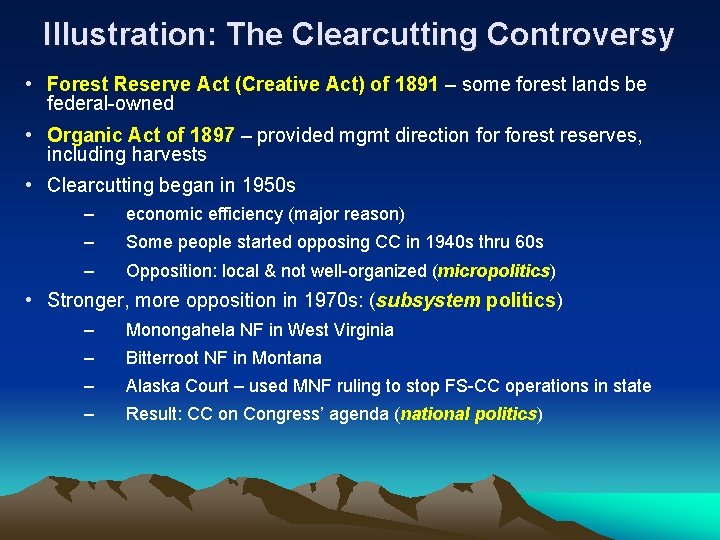

Illustration: The Clearcutting Controversy • Forest Reserve Act (Creative Act) of 1891 – some forest lands be federal-owned • Organic Act of 1897 – provided mgmt direction forest reserves, including harvests • Clearcutting began in 1950 s – economic efficiency (major reason) – Some people started opposing CC in 1940 s thru 60 s – Opposition: local & not well-organized (micropolitics) • Stronger, more opposition in 1970 s: (subsystem politics) – Monongahela NF in West Virginia – Bitterroot NF in Montana – Alaska Court – used MNF ruling to stop FS-CC operations in state – Result: CC on Congress’ agenda (national politics)

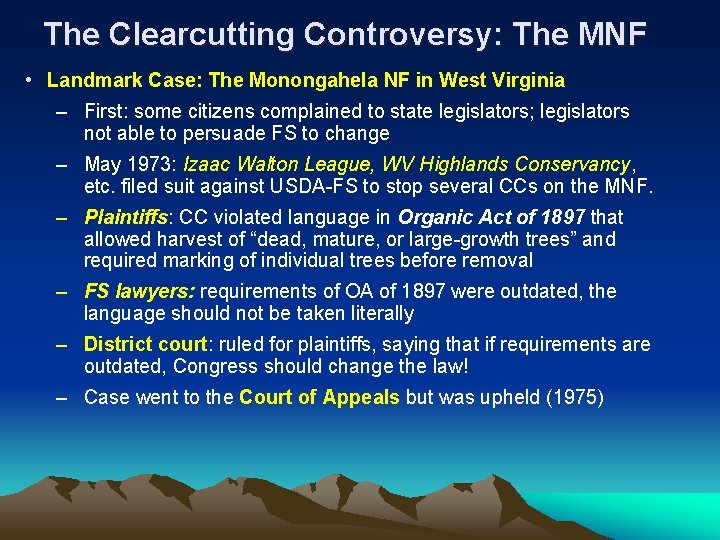

The Clearcutting Controversy: The MNF • Landmark Case: The Monongahela NF in West Virginia – First: some citizens complained to state legislators; legislators not able to persuade FS to change – May 1973: Izaac Walton League, WV Highlands Conservancy, etc. filed suit against USDA-FS to stop several CCs on the MNF. – Plaintiffs: CC violated language in Organic Act of 1897 that allowed harvest of “dead, mature, or large-growth trees” and required marking of individual trees before removal – FS lawyers: requirements of OA of 1897 were outdated, the language should not be taken literally – District court: ruled for plaintiffs, saying that if requirements are outdated, Congress should change the law! – Case went to the Court of Appeals but was upheld (1975)

The Clearcutting Controversy: The BNF • Bitterroot National Forest in MT– Another Landmark Case – Similar to MNF. – Sen Metcalf asked Dean Arnold Bolle of Univ of Montana School of Forestry to conduct study of FS practices – Bolle Report (1970) criticized the FS: concluded CC units were too large, CC were used where other methods would have been appropriate, reforestation costs much higher than revenues from poor sites – BNF issues attracted national attention – 1971: Sierra Club published CC: The deforestation of America; discussed the MNF case and called for a new forest policy

The Clearcutting Controversy Result: CC on Congress’ agenda (national politics) • Congressional hearings (Sen. Church of Idaho, led) –> developed harvest guidelines, FS accepted guidelines • NFMA (1976) – passed as result of CC being on Congress’ agenda • NFMA - USDA Sec to develop regulations • To include IDTs (interdisciplinary teams) in planning • Mandated public participation in planning • Indication that past harvest policy (given in OA of 1897) was no longer acceptable, and there was a need to modify old policy • Today – Is CC still an issue?

Initial Realities About the Political Process: About Problems 1. Events in society are interpreted in different ways by different people at different times. 2. Many problems may result from the same event. 3. Not all public problems are acted on in government. 4. Many private problems are acted on in government. 5. Many private problems are acted on in government as though they were public problems. 6. Most problems are not solved by government, though many are acted on there. 7. Policymakers are not faced with a given problem. 8. Most people do not maintain interest in other people’s problems. 9. Public problems may lack a supporting public among those directly affected.

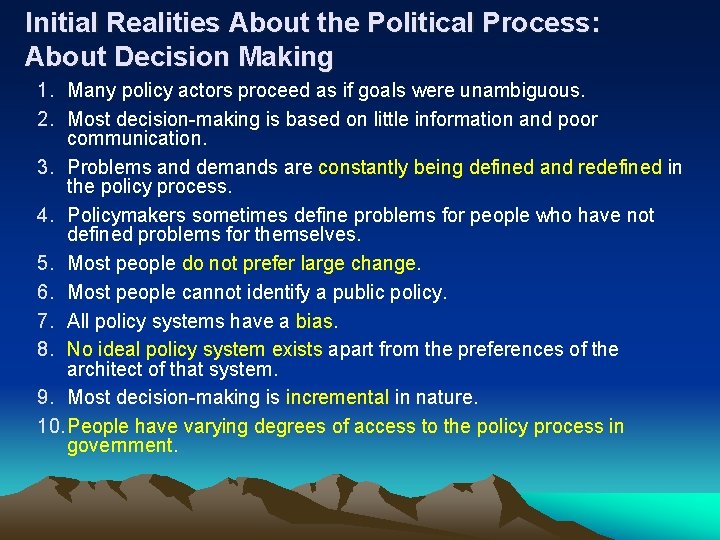

Initial Realities About the Political Process: About Decision Making 1. Many policy actors proceed as if goals were unambiguous. 2. Most decision-making is based on little information and poor communication. 3. Problems and demands are constantly being defined and redefined in the policy process. 4. Policymakers sometimes define problems for people who have not defined problems for themselves. 5. Most people do not prefer large change. 6. Most people cannot identify a public policy. 7. All policy systems have a bias. 8. No ideal policy system exists apart from the preferences of the architect of that system. 9. Most decision-making is incremental in nature. 10. People have varying degrees of access to the policy process in government.

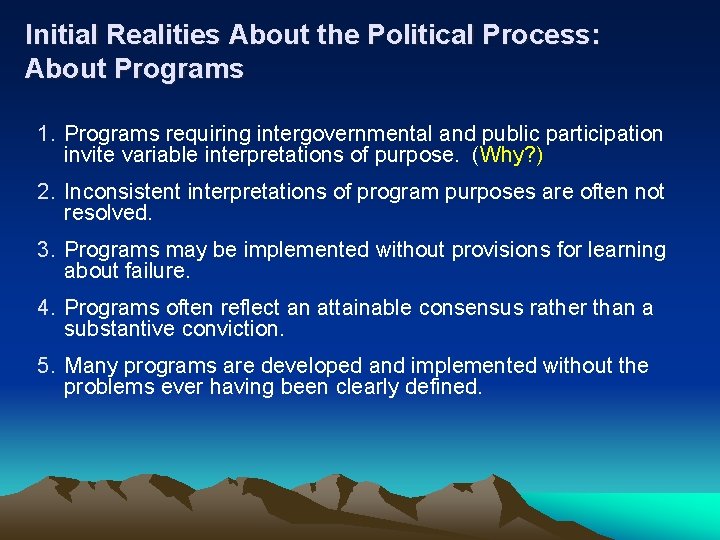

Initial Realities About the Political Process: About Programs 1. Programs requiring intergovernmental and public participation invite variable interpretations of purpose. (Why? ) 2. Inconsistent interpretations of program purposes are often not resolved. 3. Programs may be implemented without provisions for learning about failure. 4. Programs often reflect an attainable consensus rather than a substantive conviction. 5. Many programs are developed and implemented without the problems ever having been clearly defined.

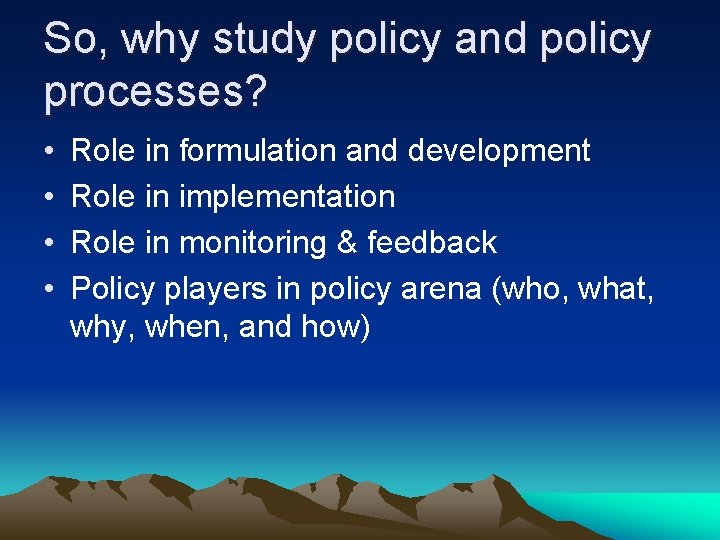

So, why study policy and policy processes? • • Role in formulation and development Role in implementation Role in monitoring & feedback Policy players in policy arena (who, what, why, when, and how)