Why do we need models There are many

![Broadcasting using shared memory Each process j {Process 0} x[0] : = v {Process Broadcasting using shared memory Each process j {Process 0} x[0] : = v {Process](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/c0a288dc15710d280ab89e5a8731c0c0/image-17.jpg)

- Slides: 21

Why do we need models? There are many dimensions of variability in distributed systems. Examples: interprocess communication mechanisms, failure classes, security mechanisms etc. Models are simple abstractions that help understand the variability -- abstractions that preserve the essential features, but hide the implementation details from observers who view the system at a higher level.

A message passing model System is a graph G = (V, E). V= set of nodes (sequential processes) E = set of edges (links or channels) (bi/unidirectional) Four types of actions by a process: - Internal action - Communication action - Input action - Output action

A reliable FIFO channel • Axiom 1. Message m sent message m received P • Axiom 2. Message propagation delay is arbitrary but finite. • Axiom 3. m 1 sent before m 2 m 1 received before m 2. Q

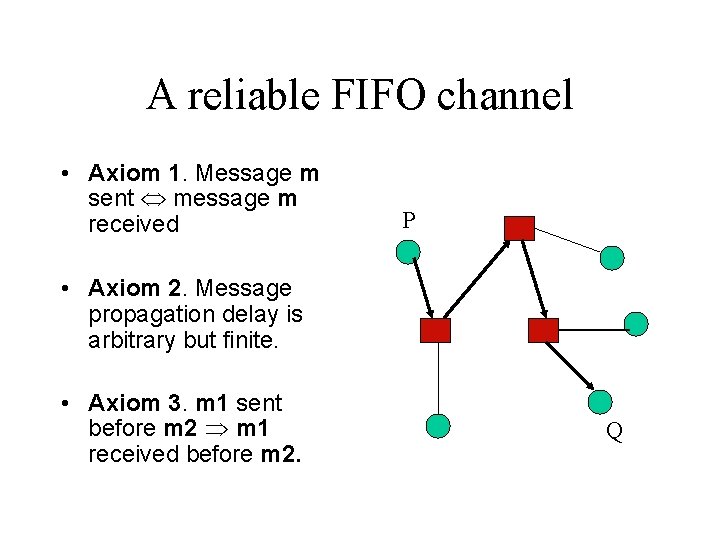

Life of a process When a message m is received Evaluate 1. predicate a with m and the local variables; 2. if predicate = true then - update internal variables; -send k (k≥ 0) messages; else skip {do nothing} end if

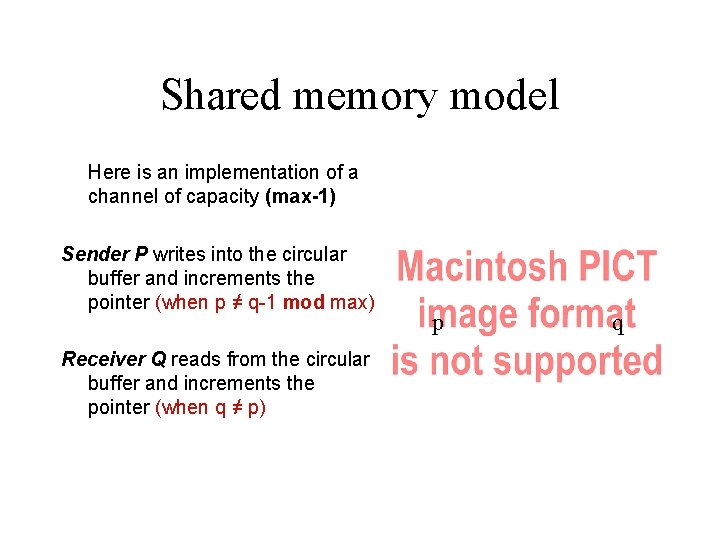

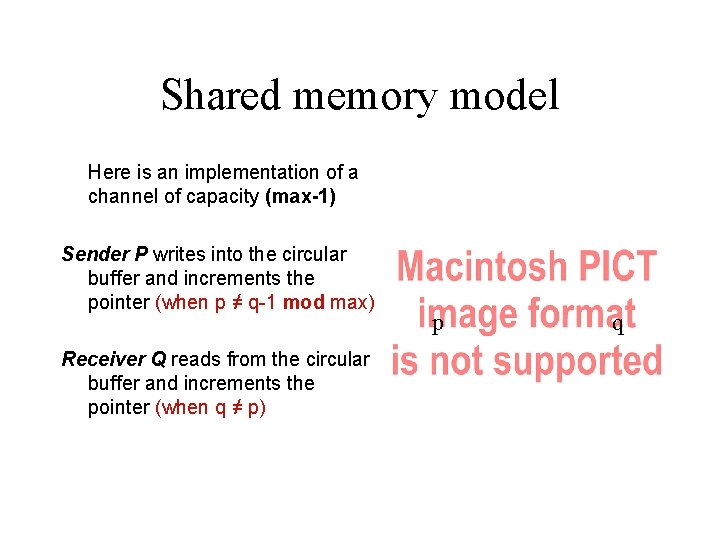

Synchrony vs. Asynchrony Synchronous clocks Local physical clocks synchronized Synchronous processes Lock-step synchrony Synchronous channels Bounded delay Synchronous message-order First-in first-out channels Synchronous Communication via communication handshaking Send & receive can be blocking or nonblocking Postal communication is asynchronous: Telephone communication is synchronous Synchronous communication or not? (1) RPC, (2) Email

Shared memory model Here is an implementation of a channel of capacity (max-1) Sender P writes into the circular buffer and increments the pointer (when p ≠ q-1 mod max) Receiver Q reads from the circular buffer and increments the pointer (when q ≠ p) p q

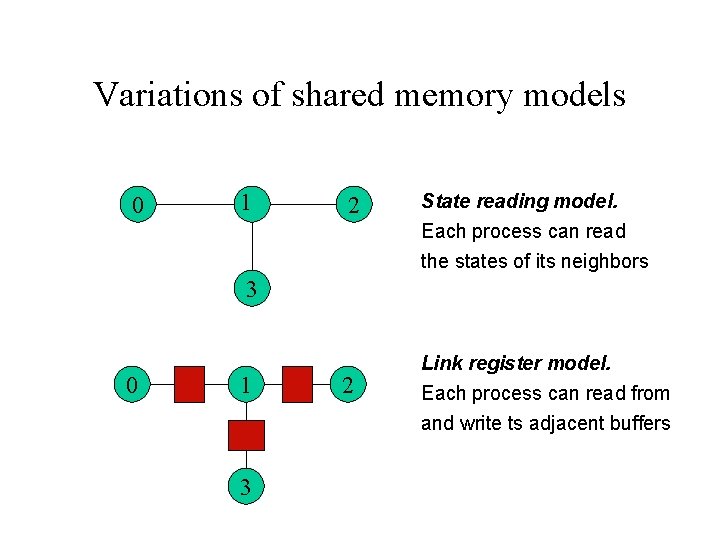

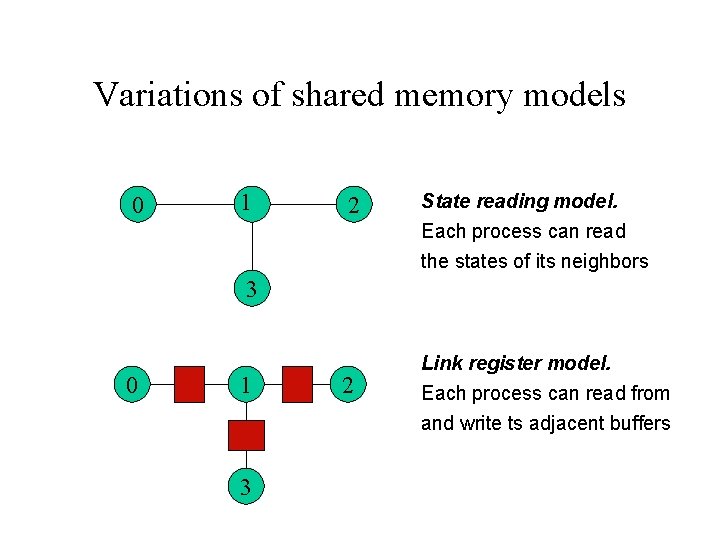

Variations of shared memory models 0 1 2 State reading model. Each process can read the states of its neighbors 3 0 1 3 2 Link register model. Each process can read from and write ts adjacent buffers

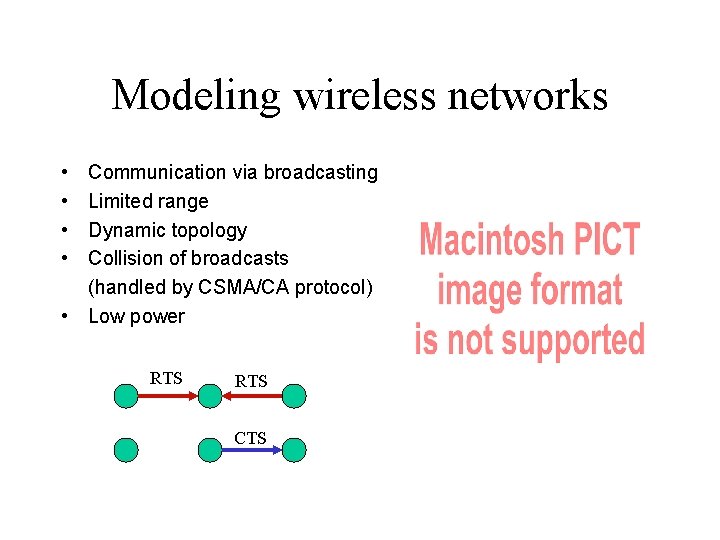

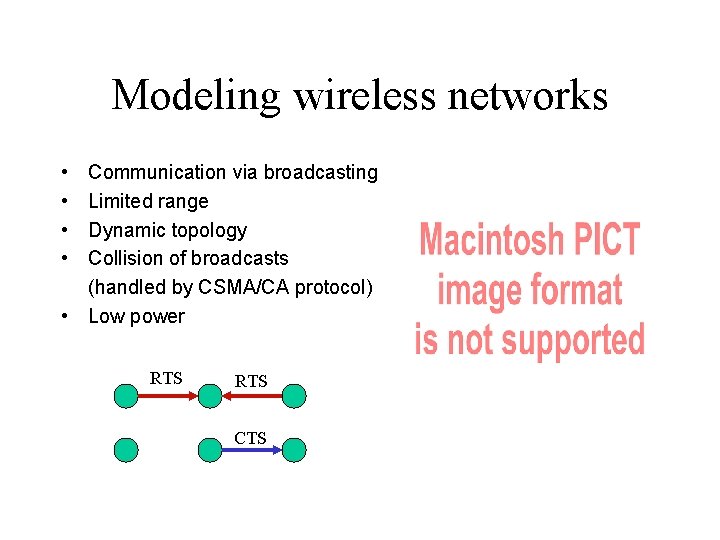

Modeling wireless networks • • Communication via broadcasting Limited range Dynamic topology Collision of broadcasts (handled by CSMA/CA protocol) • Low power RTS CTS

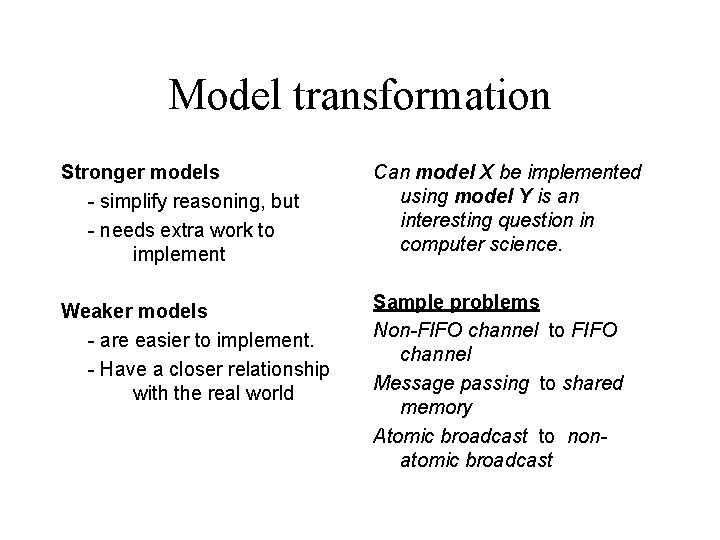

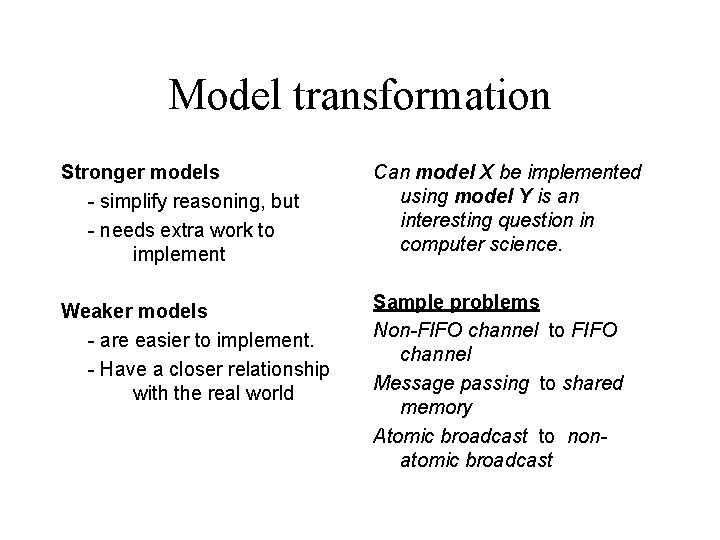

Weak vs. Strong Models One object (or operation) of a strong model = More than one objects (or operations) of a weaker model. Examples Often, weaker models are synonymous with fewer restrictions. Asynchronous is weaker than synchronous. One can add layers to create a stronger model from weaker one). HLL model is stronger than assembly language model. Bounded delay is stronger than unbounded delay (channel)

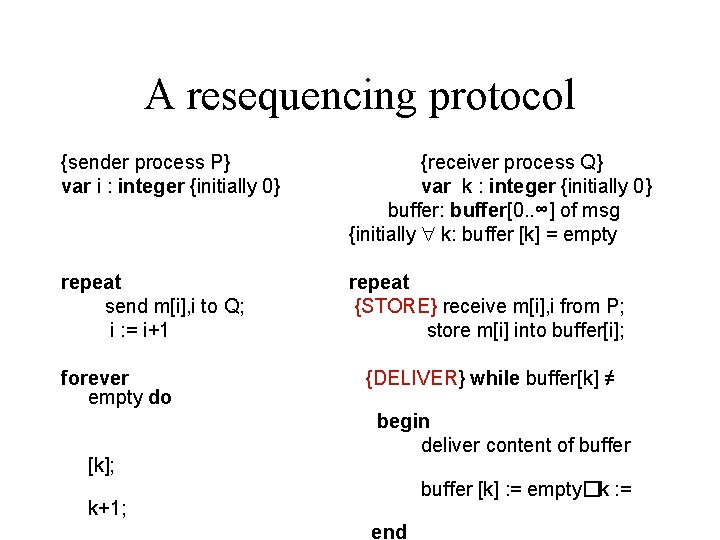

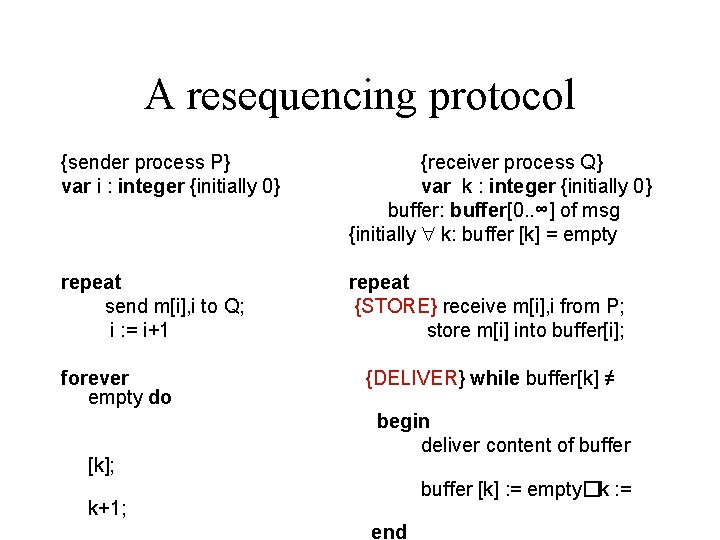

Model transformation Stronger models - simplify reasoning, but - needs extra work to implement Can model X be implemented using model Y is an interesting question in computer science. Weaker models - are easier to implement. - Have a closer relationship with the real world Sample problems Non-FIFO channel to FIFO channel Message passing to shared memory Atomic broadcast to nonatomic broadcast

A resequencing protocol {sender process P} var i : integer {initially 0} {receiver process Q} var k : integer {initially 0} buffer: buffer[0. . ∞] of msg {initially k: buffer [k] = empty repeat send m[i], i to Q; i : = i+1 repeat {STORE} receive m[i], i from P; store m[i] into buffer[i]; forever empty do [k]; {DELIVER} while buffer[k] ≠ begin deliver content of buffer [k] : = empty�k : = k+1; end

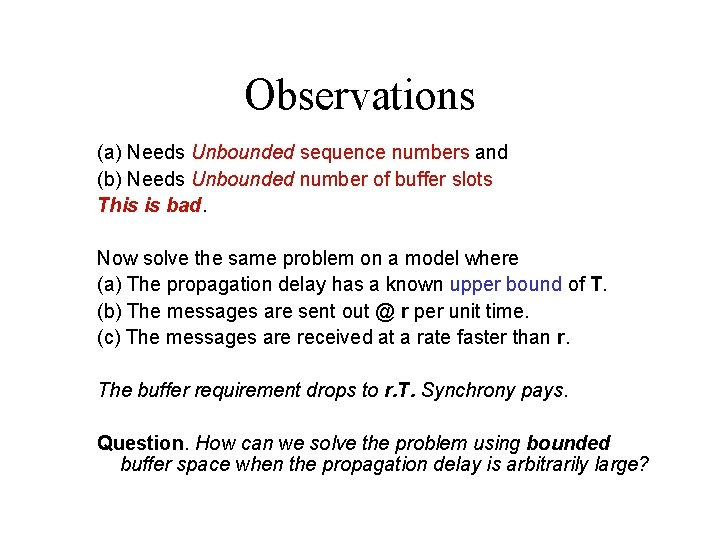

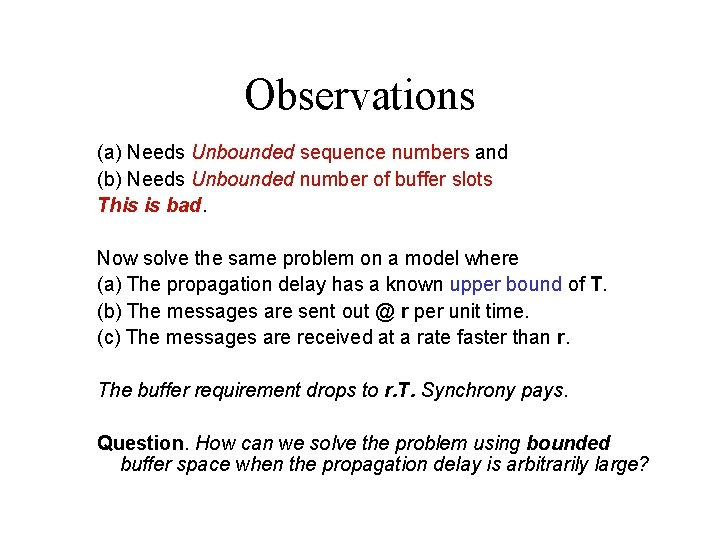

Observations (a) Needs Unbounded sequence numbers and (b) Needs Unbounded number of buffer slots This is bad. Now solve the same problem on a model where (a) The propagation delay has a known upper bound of T. (b) The messages are sent out @ r per unit time. (c) The messages are received at a rate faster than r. The buffer requirement drops to r. T. Synchrony pays. Question. How can we solve the problem using bounded buffer space when the propagation delay is arbitrarily large?

Non-atomic to atomic broadcast We now include crash failure as a part of our model. First realize what the difficulty is with a naïve approach: {process i is the sender} for j = 1 to N-1 (j ≠ i) send message m to neighbor[j] What if the sender crashes at the middle? Suggest an algorithm for atomic broadcast.

Other classifications Reactive vs Transformational systems A reactive system never sleeps (like: a server, or a token ring) A transformational (or non-reactive systems) reaches a fixed point after which no further change occurs in the system Named vs Anonymous systems In named systems, process id is a part of the algorithm. In anonymous systems, it is not so. All are equal. (-) Symmetry breaking is often a challenge. (+) Saves log N bits. Easy to switch one process by another with no side effect)

Model and complexity Many measures o o o Space complexity Time complexity Message complexity Bit complexity Round complexity Consider broadcasting in an n-cube (n=3) source

Broadcasting using messages {Process 0} sends m to neighbors {Process i > 0} repeat receive message m {m contains the value}; if m is received for the first time then x[i] : = m. value; send x[i] to each neighbor j > I else discard m end if forever What is the (1) message complexity (2) space complexity per process? Each process j has a variable x[j] initially undefined

![Broadcasting using shared memory Each process j Process 0 x0 v Process Broadcasting using shared memory Each process j {Process 0} x[0] : = v {Process](https://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image/c0a288dc15710d280ab89e5a8731c0c0/image-17.jpg)

Broadcasting using shared memory Each process j {Process 0} x[0] : = v {Process i > 0} repeat if a neighbor j < i : x[i] ≠ x[j] then x[i] : = x[j] {this is a step} else skip end if forever What is the time complexity? How many steps are needed? Can be arbitrarily large! has a variable x[j] initially undefined

Broadcasting using shared memory Each process j Now, use “large atomicity”, where in one step, a process can read the states of ALL its neighbors. What is the time complexity? How many steps are needed? The time complexity is now O(n 2) has a variable x[j] initially undefined

Complexity in rounds Rounds are truly defined for synchronous systems. An asynchronous round consists of a number of steps where every process (including the slowest one) takes at least one step. How many rounds do you need to complete the broadcast? Each process j has a variable x[j] initially undefined

Exercises Consider an anonymous distributed system consisting of N processes. The topology is a completely connected network, and the links are bidirectional. Propose an algorithm using which processes can acquire unique identifiers. (Hint: use coin flipping, and organize the computation in rounds).

Exercises Alice and Bob enter into an agreement: whenever one falls sick, (s)he will call the other person. Since making the agreement, no one called the other person, so both concluded that they are in good health. Assume that the clocks are synchronized, communication links are perfect, and a telephone call requires zero time to reach. What kind of interprocess communication model is this?