Whatever I got you gonna get HIV risk

- Slides: 27

Whatever I got, you gonna get: HIV risk and perception of male condoms among incarcerated African American women in North Carolina Chaunetta Jones, MA, MPH Office of Health Communication and Education Food and Drug Administration

Background • HIV disproportionately affects African American women in the Southeastern U. S. 1 -3 • For reasons not completely understood, women who have been in prison carry a greater lifetime risk of HIV. 4 • HIV is five times as prevalent among incarcerated African American (AA) women in North Carolina (NC) as among their unincarcerated AA counterparts. 5, 6

Background • Outside prison, HIV transmission is primarily driven by sex with men; however, decisionmaking surrounding condom use is incompletely understood. • Incarceration, substance abuse, lifetime trauma, and transactional sex (TS) are closely linked HIV risk factors in our study population and impact perceptions and decision-making surrounding condom use.

Background • History of incarceration has been associated with unstable partnerships and partner concurrency. 7 • Sexual and physical abuse are important contributors to sexual risk behavior and specifically HIV risk. 8 -10 • Childhood sexual abuse (CSA), intimate partner violence (IPV), and resulting psychological trauma play a central role in the lives of incarcerated HIVpositive and at-risk women and affect their decisionmaking surrounding condom use. 11 -13

Methods • These data are part of a parent study designed to explore the differences in HIV risk factors between HIV-positive and HIV-negative women in prison in NC. – The Social Ecological Model was used as a conceptual framework to explore risk on multiple levels. 14 • Audiotaped qualitative interviews were conducted with 29 AA women (15 HIV-positive, 14 HIV-negative) by two interviewers.

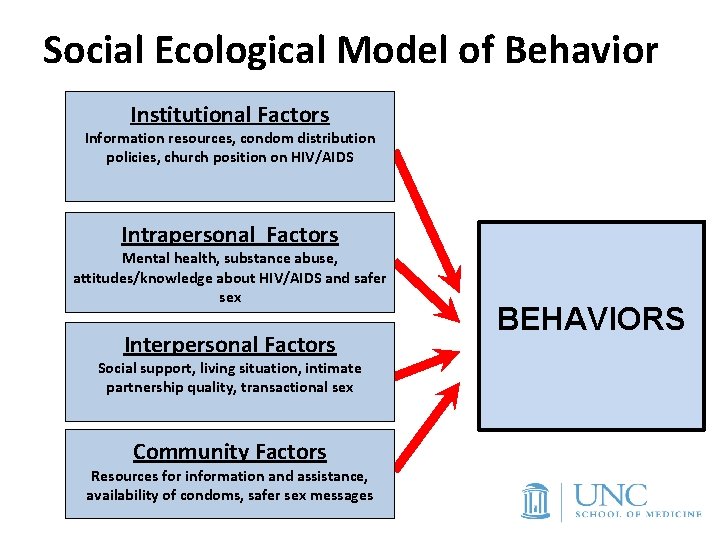

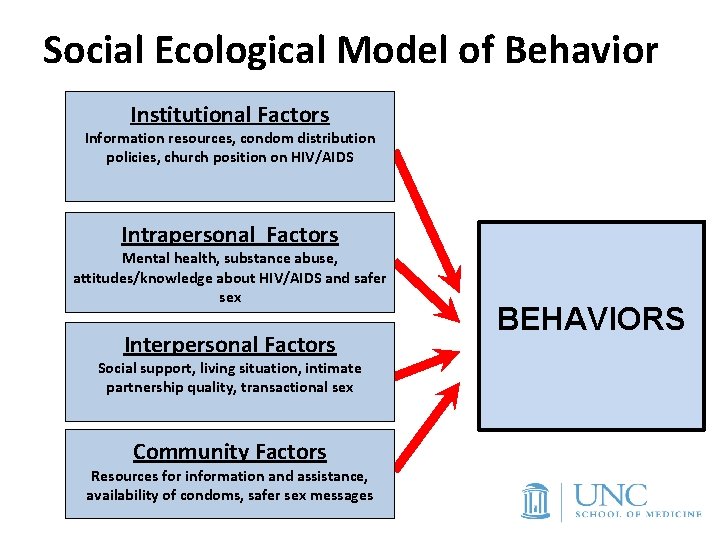

Social Ecological Model of Behavior Institutional Factors Information resources, condom distribution policies, church position on HIV/AIDS Intrapersonal Factors Mental health, substance abuse, attitudes/knowledge about HIV/AIDS and safer sex Interpersonal Factors Social support, living situation, intimate partnership quality, transactional sex Community Factors Resources for information and assistance, availability of condoms, safer sex messages BEHAVIORS

Methods • Interviews explored potential pre-incarceration HIV risk factors on multiple levels (e. g. community, interpersonal, intrapersonal). • Participants were interviewed within three months after entry into the NC prison system. • Following social ecological theory, we explored pre-incarceration HIV risk factors from community-level (e. g. condom accessibility) to intrapersonal (e. g. sexual practices).

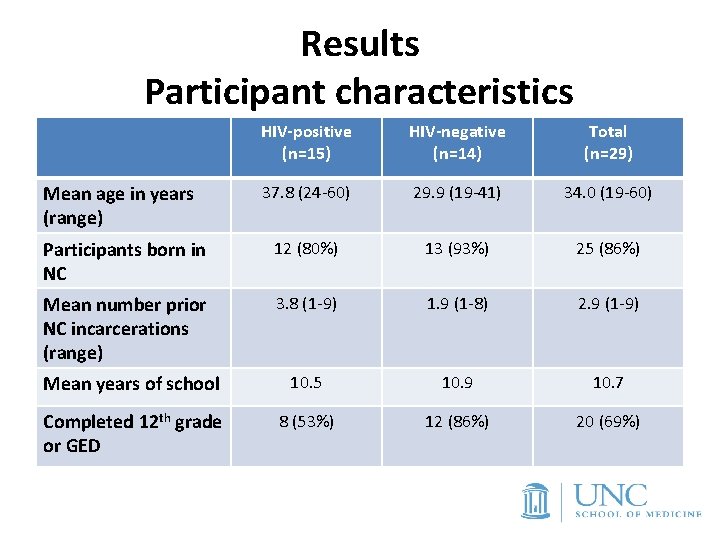

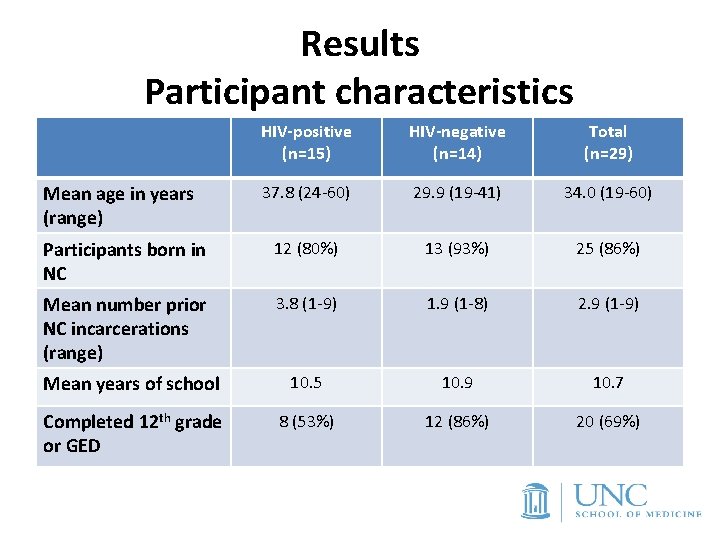

Results Participant characteristics HIV-positive (n=15) HIV-negative (n=14) Total (n=29) 37. 8 (24 -60) 29. 9 (19 -41) 34. 0 (19 -60) Participants born in NC 12 (80%) 13 (93%) 25 (86%) Mean number prior NC incarcerations (range) 3. 8 (1 -9) 1. 9 (1 -8) 2. 9 (1 -9) Mean years of school 10. 5 10. 9 10. 7 Completed 12 th grade or GED 8 (53%) 12 (86%) 20 (69%) Mean age in years (range)

Results Participant characteristics HIV-positive (n=15) HIV-negative (n=14) Total (n=29) Biological 14 (93%) 9 (64%) children Gender of pre-incarceration sexual partners 23 (79%) Male 11 (73%) 7 (50%) 18 (62%) Male and female 4 (27%) 3 (21%) 7 (24%) 0 4 (29%) 4 (14%) Female

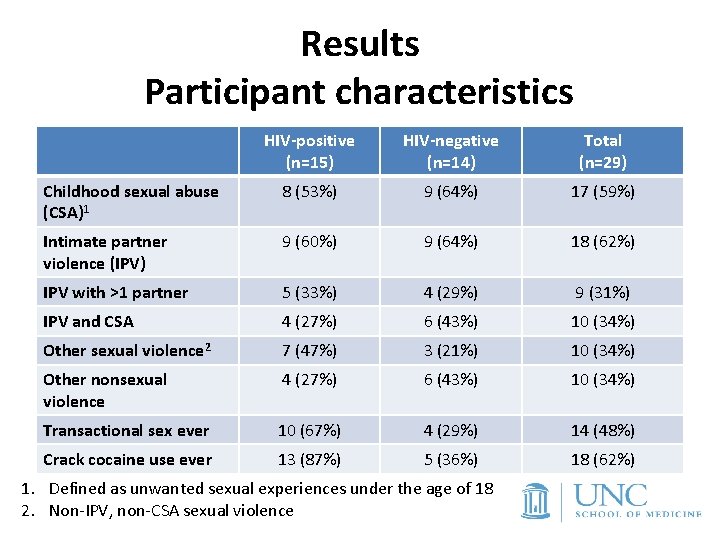

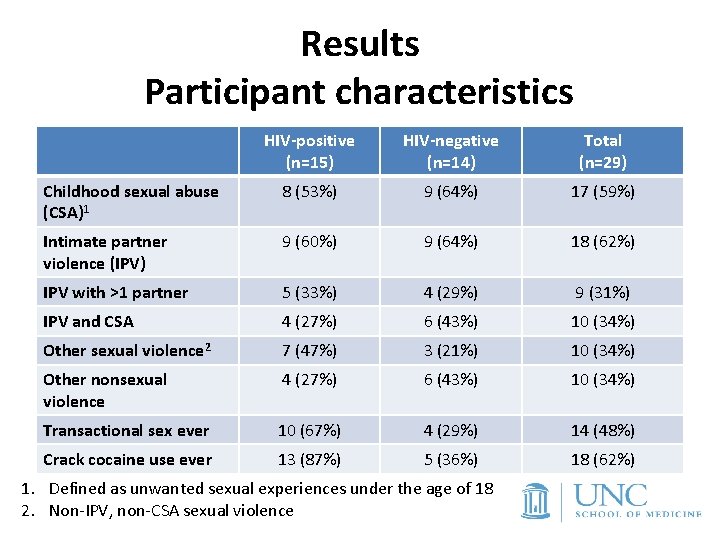

Results Participant characteristics HIV-positive (n=15) HIV-negative (n=14) Total (n=29) Childhood sexual abuse (CSA)1 8 (53%) 9 (64%) 17 (59%) Intimate partner violence (IPV) 9 (60%) 9 (64%) 18 (62%) IPV with >1 partner 5 (33%) 4 (29%) 9 (31%) IPV and CSA 4 (27%) 6 (43%) 10 (34%) Other sexual violence 2 7 (47%) 3 (21%) 10 (34%) Other nonsexual violence 4 (27%) 6 (43%) 10 (34%) Transactional sex ever 10 (67%) 4 (29%) 14 (48%) Crack cocaine use ever 13 (87%) 5 (36%) 18 (62%) 1. Defined as unwanted sexual experiences under the age of 18 2. Non-IPV, non-CSA sexual violence

Results: Condom use in partnerships • Women reported low rates of consistent condom use with male partners and no barrier methods with female partners. • Condoms were described in contrast to relationship trust: among women with children (n=23), few used condoms with fathers of their children. • Several women described continued unprotected sex with men who gave them STIs or had concurrent female partners.

Results: Decision-making and condom use Participants reported three main factors that they considered when making decisions about whether or not to use condoms: 1) How much they could “trust” their partner, a word that encompassed emotional trust as well as an assumption that both partners were monogamous and free of HIV/STI or that HIV/STI status had been disclosed 2) Their desire for children or lack of opposition to becoming pregnant, and/or 3) Deferring to a male partner’s preference.

Results: Decision-making and condom use • A 28 -year-old HIV-negative woman with both male and female sexual partners discusses her decisionmaking about condom use with male partners on her perception of exclusivity in the relationship: “With my boyfriend, we use a condom most of the time. With my friend, we used a condom all the time because he has a girlfriend. ”

Results: Decision-making and condom use • A 27 -year-old HIV-positive woman with children described her choices regarding condom use in what she thought was a committed relationship: “Myself, let’s see, I’m not going to say, because I wasn’t having casual sex. I was in a relationship. So back then I would say being stupid. Thinking I could trust him not wanting to wear a condom anymore. He my boyfriend, he okay. And not understanding that okay wasn’t okay. ”

Results: Decision-making and condom use • A 48 -year-old HIV-positive woman with three children and both male and female past sexual partners also addressed perceived commitment as a factor in forgoing condoms: “In oral sex, as well as sex, I always use a condom, no matter what. Unless later on down the line, we decide to be girlfriend and boyfriend. They want a live-in partner then, so I just don’t use them. ”

Results: Barriers to condom use • At the individual level, women worried about HIV and sexually transmitted infections and described the relevance of condoms to these concerns. • Interpersonal-level barriers to condom use included relationship power dynamics and widespread intimate partner violence. • At the community level, all participants described ready availability of condoms.

Results: Condoms, transactional sex and substance use: • Prevalent transactional sex (TS) and crack cocaine use among HIV -positive women was described in association with low condom use. • All HIV-positive and HIV-negative women reporting TS also reported crack cocaine use. • Most of the HIV-negative women related small numbers of incidents in which they accepted money or goods for a sexual act. HIV-positive women related periods of time in which TS was linked to prolonged substance use and was a regular occurrence. • Most of the women who related a history of TS linked their TS to drug use, trading sex for drugs or for money to buy drugs.

Condoms, transactional sex and substance use: A 48 -year-old HIV-positive woman “So if I’m out here with all of you guys and y’all don’t carry condoms and I’m in this circle and we sleeping with all the same different tricks, we probably sleeping with all the same men that’s out here getting high together, it’s all going to be a circle. Whatever I got, you gonna get. Whatever you got, I’m a get, if I’m not safe. ”

Condoms, transactional sex and substance use: Another 48 year-old HIV -positive woman “I moved to [another city] one time and I was on crack real bad. These drug dealers or so-called pimps or whatever, I wanted to get high. I ain’t care how I got high, so I tricked without condoms or I’ll have sex with a couple boyfriends without condoms. Who does that? You don’t know these people for real, now that I got [HIV]. You don’t know these people. ”

Next steps: Quantitative phase • Qualitative data was used to build a quantitative instrument reflecting conceptual model. • Quantitative instrument (administered via ACASI) uses a combination of previously validated and newly created measures to assess HIV risk on multiple levels. – e. g. Condom Use Self Efficacy Scale 15 – Targeted questions to assess decision-making surrounding sexual practices (e. g. sex with women, fertility desire, transactional sex)

Conclusions • Study participants described a high level of condom awareness and accessibility, however, multiple factors limited consistent condom use. • HIV risk reduction efforts must extend beyond condom promotion to address women's self-efficacy 16 or provide female-controlled methods of HIV prevention. • Women who have sex only occasionally with male partners, particularly in a situation involving fertility desire or TS or other coercive circumstances may not disclose these practices or see themselves as at risk for HIV. 17

Conclusions • The social harms conveyed by TS, crack cocaine, and lack of economic power warrant development of interventions to decrease HIV risk, target and improve lifetime health for these women. • Many of the factors limiting condom use on this population reflected structural risk factors for HIV, such as poverty, limited partner choice, acceptance of concurrency, and prevalent incarceration. • These results and research in similar populations underscore the urgency of understanding the forces shaping disproportionately high HIV incidence in this population in addition to traditional individual-level factors.

Acknowledgements • • • Sharon D. Parker Kathryn Muessig Catherine Grodensky Carol Golin Cathie Fogel David A. Wohl • The North Carolina Department of Correction • Wardens and staff of the study facilities • Study participants • The University of North Carolina CFAR • The UNC CFAR Criminal Justice Working Group This project was supported by the NIH (F 32 DA 030268). Additional support was provided by the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (P 30 AI 50410).

References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, et al. Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006 -2009. Plo. S One. 2011; 6(8): e 17502. Hodder SL, Justman J, Hughes JP, et al. HIV Acquisition Among Women From Selected Areas of the United States: A Cohort Study. Annals of Internal Medicine 2013; 158: 10 -8. Greenfeld LA, & Snell, T. L. . Women offenders (Bureau of Justice Special Report NCJ 175688). Washington, DC: Department of Justice. 1999. Staton-Tindall M, Leukefeld C, Palmer J, Oser C, Kaplan A, Krietemeyer J, et al. Relationships and HIV risk among incarcerated women. Prison J. 2007; 87(1): 143 -65. N. C. Epidemiologic Profile for HIV/STD Prevention and Care Planning (12/11) http: //epi. publichealth. nc. gov/cd/stds/figures/Epi_Profile_2011. pdf DOC RESEARCH AND PLANNING Automated System Query (A. S. Q. DOC 3. 0 b ) Prison Population 3 -31 -2012 http: //webapps 6. doc. state. nc. us/apps/asq. Ext/ASQ. Khan MR, Wohl DA, Weir SS, Adimora AA, Moseley C, Norcott K, et al. Incarceration and risky sexual partnerships in a southern US city. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2008; 85(1): 100 -13.

References 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. Campbell JC, Baty ML, Ghandour RM, Stockman JK, Francisco L, Wagman J. The intersection of intimate partner violence against women and HIV/AIDS: a review. International journal of injury control and safety promotion. 2008; 15(4): 221 -31. Pence BW, Mugavero MJ, Carter TJ, Leserman J, Thielman NM, Raper JL, et al. Childhood Trauma and Health Outcomes in HIV-Infected Patients: An Exploration of Causal Pathways. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes (1999). 2012; 59(4): 409 -16. Wingood GM, Di. Clemente RJ, Seth P. Improving health outcomes for IPVexposed women living with HIV. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013 Sep 1; 64(1): 1 -2. Machtinger EL, Wilson TC, Haberer JE, Weiss DS. Psychological Trauma and PTSD in HIV-Positive Women: A Meta-Analysis. AIDS and behavior. 2012. Whetten K, Leserman J, Lowe K, Stangl D, Thielman N, Swartz M, et al. Prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and physical trauma in an HIV-positive sample from the deep South. American journal of public health. 2006; 96(6): 1028 -30. Harlow CW. Prior Abuse Reported by Inmates and Probationers. Washington, DC: U. S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics. 1999.

References 14. Mc. Leroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health education quarterly. 1988; 15(4): 351 -77. 15. Brafford, LJ and Beck, KH. Development and validation of a condom self-efficacy scale for college students. Journal of American College Health. 1991, 39, 219– 225. 16. Raiford, JL, Wingood, GM, & Di. Clemente, RJ. Correlates of consistent condom use among HIV-positive African American women. Women & Health, 46(2 -3), 41 -58. 2007. 17. Farel CE, Parker SD, Muessig KE, Grodensky CA. , Jones C, Golin CE, Fogel, CI, Wohl DA. Sexuality, Sexual Practices, and HIV Risk among Incarcerated African American Women in North Carolina. Women's Health Issues, 23 -6 e 357–e 364. 2013.

Study contact PI: Claire Farel, MD, MPH UNC Institute for Global Health and Infectious Diseases cfarel@med. unc. edu