What is a Revolution Although the term revolution

- Slides: 11

What is a Revolution? Although the term “revolution” is used a great deal in contemporary culture, an actual revolution that completely transforms a society is quite rare. However, during the period 1950 -1990, a number of the world’s regions witnessed events that could legitimately be termed revolutionary. Historian Mehran Kamrava provides us with a solid working definition of the term “revolution” – a definition that will help us to understand better many of the events portrayed in Satrapi’s Persepolis.

Mehran Kamrava’s Definition of “Revolution” Revolutions involve “ingredients not always easy to come by: millions of people for whom pursuing a cause has become more pressing than the chores of daily life; the collapse of state institutions and their replacement by other, new ones; and the reconstitution of a political order radically different from that of the old order. These changes resonate not only domestically, but also regionally and globally, affecting balance-of-power equations, alliances, and international economics” (138).

Planned vs. Spontaneous Revolutions Kamrava notes that the Iranian Revolution was spontaneous in nature, meaning that it evolved in a haphazard, unstructured way. For contrast, he points to the Chinese or Cuban Revolutions, which were planned carefully over long periods of timely by highly organized guerrilla movements (139). Why is the distinction important? Spontaneous revolutions often enable inexperienced or highly radical individuals to rise quickly to power, thus increasing the possibility for violence and instability.

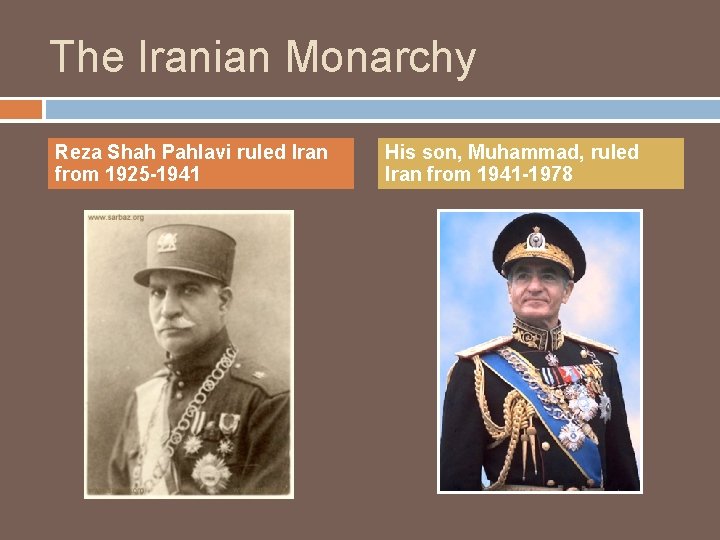

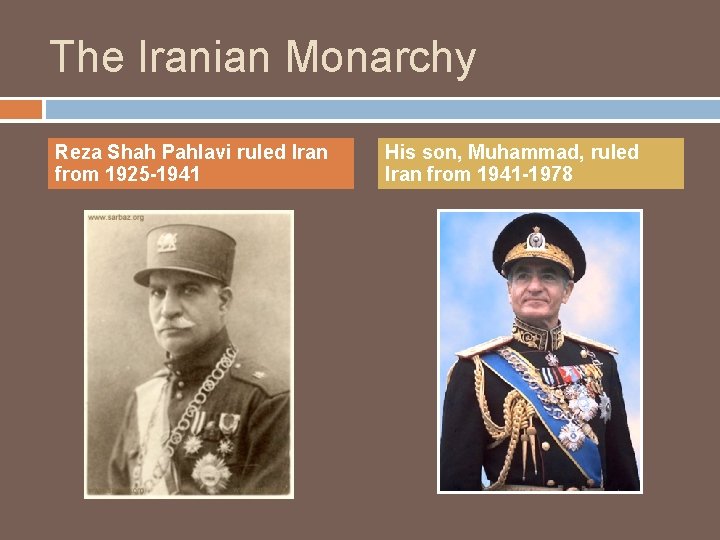

The Iranian Monarchy Reza Shah Pahlavi ruled Iran from 1925 -1941 His son, Muhammad, ruled Iran from 1941 -1978

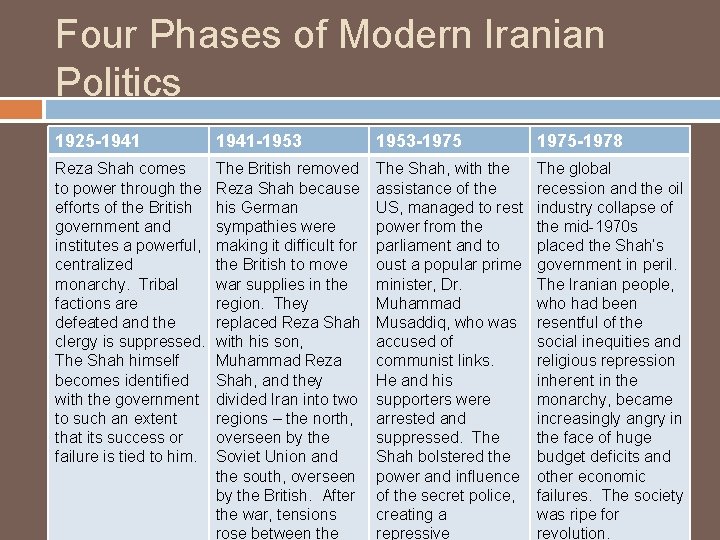

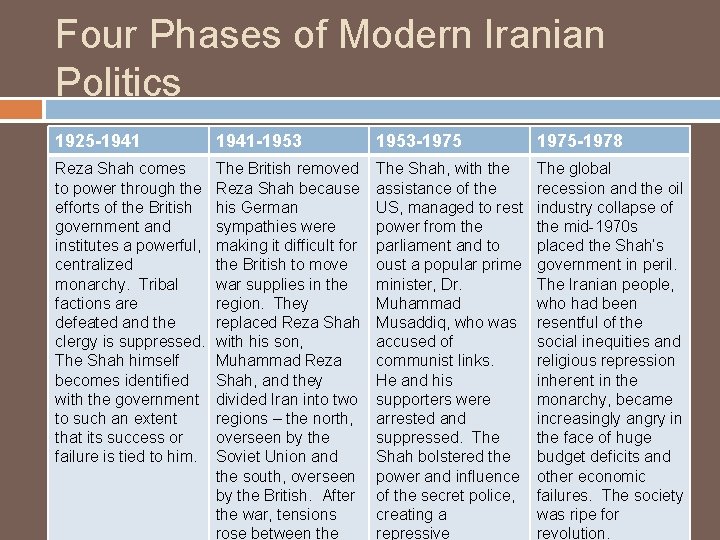

Four Phases of Modern Iranian Politics 1925 -1941 -1953 -1975 -1978 Reza Shah comes to power through the efforts of the British government and institutes a powerful, centralized monarchy. Tribal factions are defeated and the clergy is suppressed. The Shah himself becomes identified with the government to such an extent that its success or failure is tied to him. The British removed Reza Shah because his German sympathies were making it difficult for the British to move war supplies in the region. They replaced Reza Shah with his son, Muhammad Reza Shah, and they divided Iran into two regions – the north, overseen by the Soviet Union and the south, overseen by the British. After the war, tensions rose between the The Shah, with the assistance of the US, managed to rest power from the parliament and to oust a popular prime minister, Dr. Muhammad Musaddiq, who was accused of communist links. He and his supporters were arrested and suppressed. The Shah bolstered the power and influence of the secret police, creating a repressive The global recession and the oil industry collapse of the mid-1970 s placed the Shah’s government in peril. The Iranian people, who had been resentful of the social inequities and religious repression inherent in the monarchy, became increasingly angry in the face of huge budget deficits and other economic failures. The society was ripe for revolution.

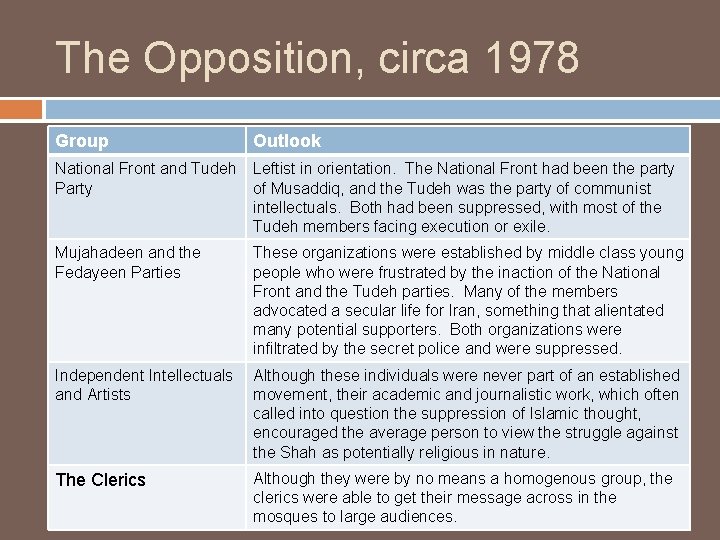

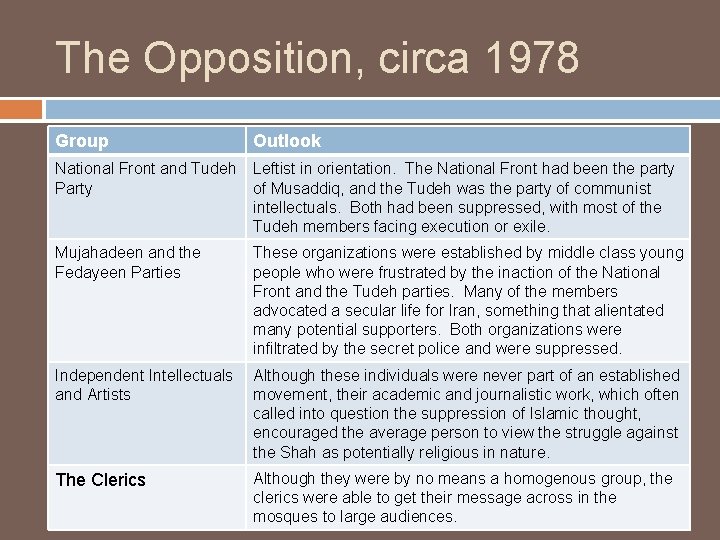

The Opposition, circa 1978 Group Outlook National Front and Tudeh Party Leftist in orientation. The National Front had been the party of Musaddiq, and the Tudeh was the party of communist intellectuals. Both had been suppressed, with most of the Tudeh members facing execution or exile. Mujahadeen and the Fedayeen Parties These organizations were established by middle class young people who were frustrated by the inaction of the National Front and the Tudeh parties. Many of the members advocated a secular life for Iran, something that alientated many potential supporters. Both organizations were infiltrated by the secret police and were suppressed. Independent Intellectuals and Artists Although these individuals were never part of an established movement, their academic and journalistic work, which often called into question the suppression of Islamic thought, encouraged the average person to view the struggle against the Shah as potentially religious in nature. The Clerics Although they were by no means a homogenous group, the clerics were able to get their message across in the mosques to large audiences.

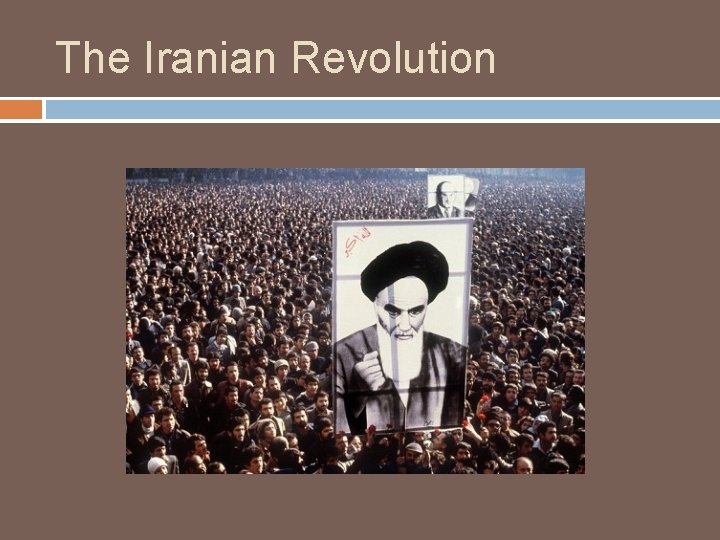

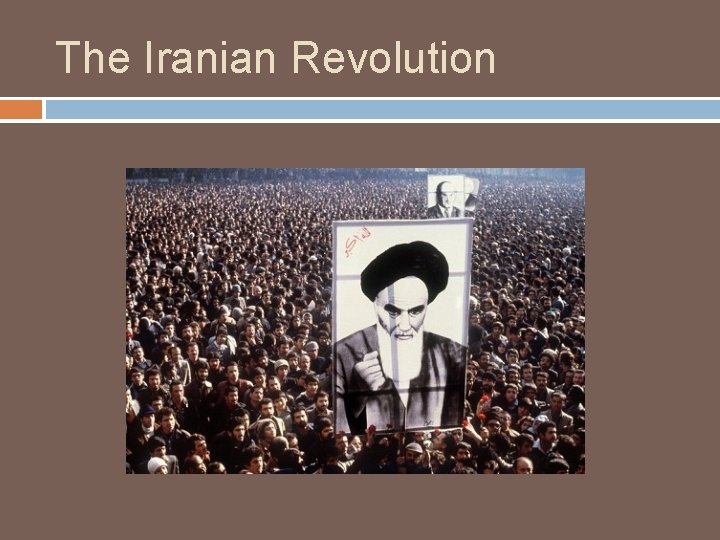

The Iranian Revolution

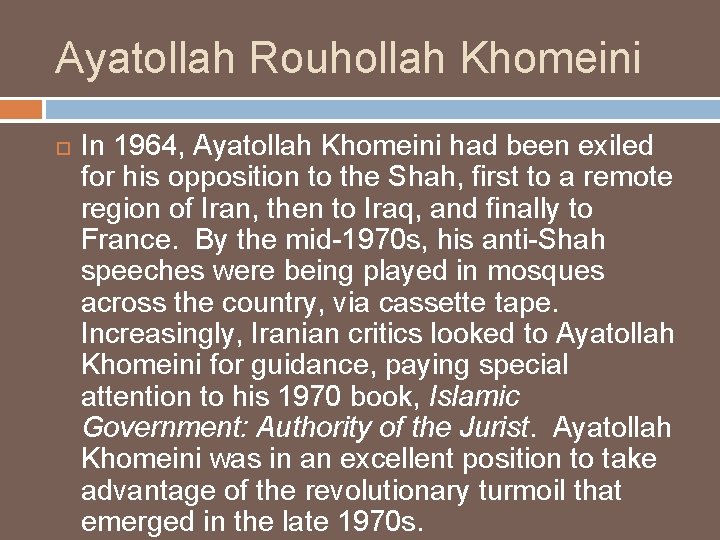

Ayatollah Rouhollah Khomeini In 1964, Ayatollah Khomeini had been exiled for his opposition to the Shah, first to a remote region of Iran, then to Iraq, and finally to France. By the mid-1970 s, his anti-Shah speeches were being played in mosques across the country, via cassette tape. Increasingly, Iranian critics looked to Ayatollah Khomeini for guidance, paying special attention to his 1970 book, Islamic Government: Authority of the Jurist. Ayatollah Khomeini was in an excellent position to take advantage of the revolutionary turmoil that emerged in the late 1970 s.

The End of the Shah’s Rule On January 18, 1979, the Shah left Iran due to “medical reasons, ” and on February 1, 1979, Ayatollah Khomeini returned to Iran – over a million people rallied in the streets of Tehran in welcome. On February 11, 1979, the military capitulated, and on March 30, 1979, the people voted to establish an Islamic Republic, with Ayatollah Khomeini as its leader.

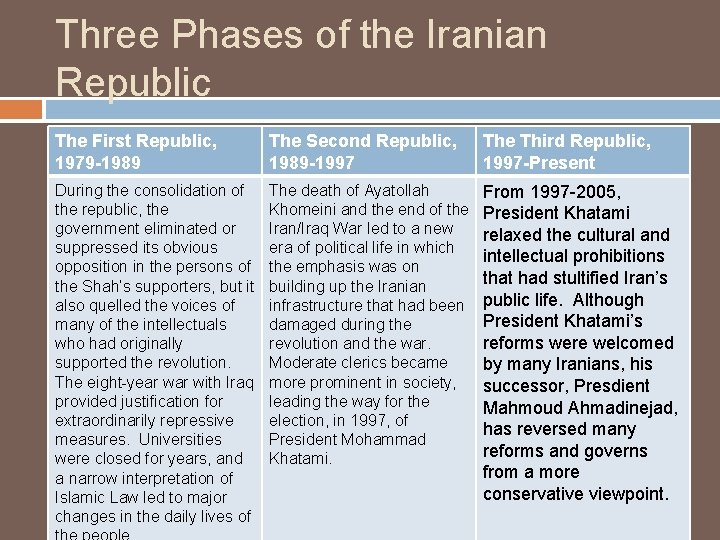

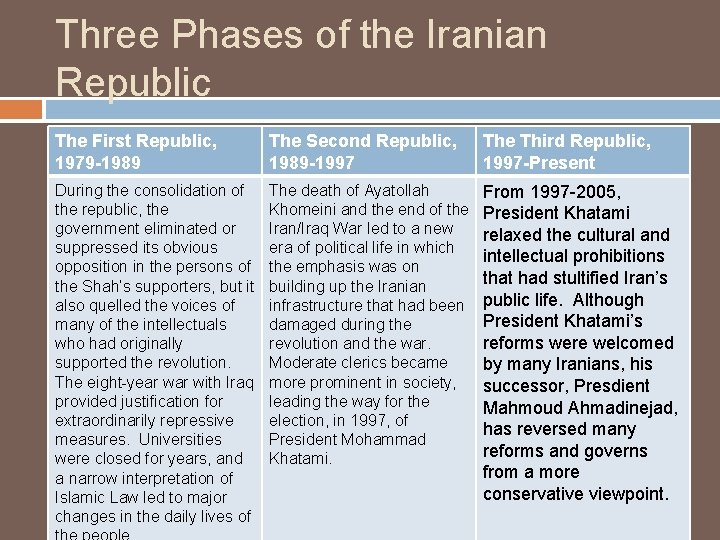

Three Phases of the Iranian Republic The First Republic, 1979 -1989 The Second Republic, 1989 -1997 The Third Republic, 1997 -Present During the consolidation of the republic, the government eliminated or suppressed its obvious opposition in the persons of the Shah’s supporters, but it also quelled the voices of many of the intellectuals who had originally supported the revolution. The eight-year with Iraq provided justification for extraordinarily repressive measures. Universities were closed for years, and a narrow interpretation of Islamic Law led to major changes in the daily lives of The death of Ayatollah Khomeini and the end of the Iran/Iraq War led to a new era of political life in which the emphasis was on building up the Iranian infrastructure that had been damaged during the revolution and the war. Moderate clerics became more prominent in society, leading the way for the election, in 1997, of President Mohammad Khatami. From 1997 -2005, President Khatami relaxed the cultural and intellectual prohibitions that had stultified Iran’s public life. Although President Khatami’s reforms were welcomed by many Iranians, his successor, Presdient Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, has reversed many reforms and governs from a more conservative viewpoint.

Satrapi’s Persepolis (20002003) This brief background presentation should help you to make sense of the politcal and cultural events that Satrapi describes in her graphic narrative, Persepolis. The primary source for this lecture was: � Kamrava, Mehran. The Modern Middle East: A Political History Since the First World War. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.