What is a human being The Meaning of

What is a human being? The Meaning of Morality in Court of Justice of the European Union Maj-Britt Höglund, Ph. D Hanken School of Economics VAKKI, 6 th-7 th February, 2020

Law and Linguistics - Applying Critical Discourse Analysis in Reading Two CJEU Cases Caveat: A very small pilot study CDA applied to jurisprudence texts only recently: work-in-progress

This study using CDA is one of many within an extensive research project Academy of Finland Funded Research Project FAirness, Morality and Equality in international and European Intellectual Property Law (FAME-IP) Ø All other studies in the project set within jurisprudence studies Ø Project coordinator: Nari Lee Professor of Intellectual Property Law Hanken Vaasa & Helsinki

Introduction Ø Law uses various value ridden concepts such as fairness, equality, and morality. Ø One example: the European patent law basically defines what may be subject to property relationship, and prohibits patenting on inventions whose commercial exploitation would be against morality such as invention on human beings. The EU biotechnology directive categorically prohibits patenting on inventions based on human embryos. Gene-editing & the need to promote morality require a proper understanding of the meaning of “human beings” as used in the terminology of the CJEU = a step in understanding the meaning of “morality” as promoted by the law.

Discourse Constructing Reality “discursive practices or systems of meaning” (Foucault, 1972: 49) which by naming objects call them into existence (Foucault, 2004: 94). (Thus, is there a reality without discourse? )

Critical Discourse Analysis - dominance and power A suitable tool to investigate a field where discourses struggle with each other for dominance A tool to interpret legal, but also extra-legal concepts. A tool to investigate who has the power over the discourse. (see, e. g. , Fairclough, 2001: 45; Mills, 2004: 38) Rarely applied to jurisprudence texts.

Point of entry: discourse of the CJEU Rhetorics for jurisprudence texts? (Ethos, Pathos & Logos; credibility & trust; values & emotions; logic & proof) Instead repertoire analysis: Gilbert, G. Nigel and Michael Mulkay (1984). Opening Pandora’s Box. A Sociological Analysis of Scientists’ Discourse. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Ten stages according to: Wetherell, Margaret & Jonathan Potter (1988). “Discourse Analysis and the Identification of Interpretive Repertoires. ” In Analysing Everyday Explanation. A Casebook of Methods. Ed. Charles Antaki. London: Sage. 168– 183.

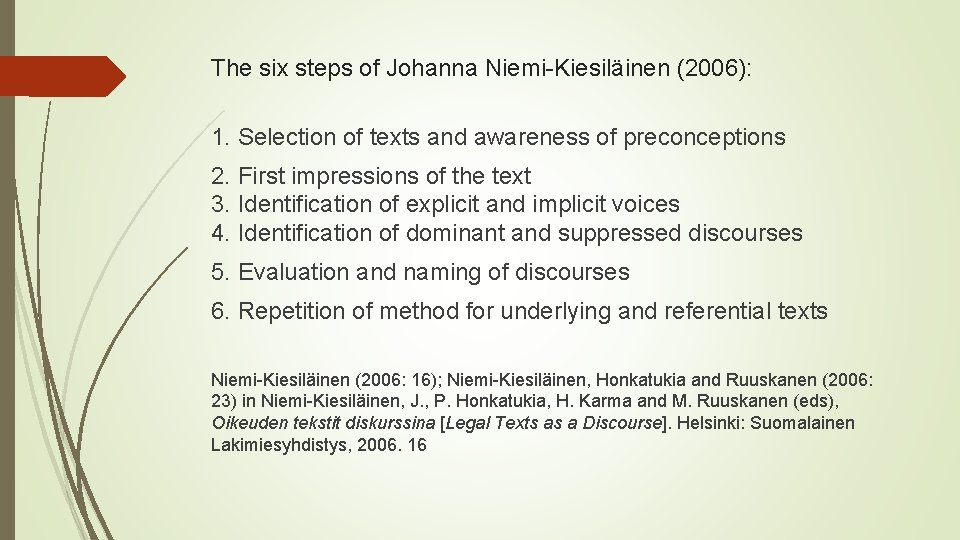

Previous research: CDA methods for jurisprudence texts Kalimo, Meyer, Mylly (2018). ”Of Values and Legitimacy Discourse Analytical Insights on the Copyright Law Case of the Court of Justice of the European Union”. The Modern Law Review. John Wiley & Sons: Oxford Also methods of Discourse Analysis: Niemi-Kiesiläinen, Honkatukia, Karma and Ruuskanen (2006: 9 -20) Niemi-Kiesiläinen, Honkatukia and Ruuskanen (2006: 21 -42) Both in Niemi-Kiesiläinen, J. , P. Honkatukia, H. Karma and M. Ruuskanen (eds), Oikeuden tekstit diskurssina [Legal Texts as a Discourse]. Helsinki: Suomalainen Lakimiesyhdistys, 2006.

The six steps of Johanna Niemi-Kiesiläinen (2006): 1. Selection of texts and awareness of preconceptions 2. First impressions of the text 3. Identification of explicit and implicit voices 4. Identification of dominant and suppressed discourses 5. Evaluation and naming of discourses 6. Repetition of method for underlying and referential texts Niemi-Kiesiläinen (2006: 16); Niemi-Kiesiläinen, Honkatukia and Ruuskanen (2006: 23) in Niemi-Kiesiläinen, J. , P. Honkatukia, H. Karma and M. Ruuskanen (eds), Oikeuden tekstit diskurssina [Legal Texts as a Discourse]. Helsinki: Suomalainen Lakimiesyhdistys, 2006. 16

Previous research: “CJEU jurisprudence as a discourse” ”In EU law, the CJEU is an active agent that uses its authority to decide on meanings and on the most suitable interpretation of a given word or larger text: it determines the ways in which words should be used in specific EU law contexts. ” Kalimo, Meyer, Mylly (2018: 289) 9

![Kalimo, Meyer, Mylly (2018: 283 -285) Objective of the study: [. . . ] Kalimo, Meyer, Mylly (2018: 283 -285) Objective of the study: [. . . ]](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h/0fba519f9a39065c1527cd3ad0d6c8a9/image-11.jpg)

Kalimo, Meyer, Mylly (2018: 283 -285) Objective of the study: [. . . ] ”to contribute to the discussion on the institutional role of the CJEU in the European value discourse, using European copyright law as an exploratory case study. ” Issues investigated: 1) Substantive law: copyright 2) CJEU as an institution 3) Method: introducing CDA Kalimo, Harri, Meyer, Trisha and Mylly, Tuomas (2018). ”Of Values and Legitimacy - Discourse Analytical Insights on the Copyright Law Case of the Court of Justice of the European Union”. The Modern Law Review. John Wiley & Sons: Oxford

Previous research: The style of the Advocate General ”From a discourse analytical perspective, the opinions of the Advocates General, which prepare but in no way bind the Court in its decision-making, are rather colourful, active, abundant and detailed. ” (Paso, 2009: 197) The AG’s style = a given. Paso, M. (2009)Viimeisellä tuomiolla. Suomen korkeimman oikeuden ja Euroopan yhteisöjen tuomioistuimen en- nakkopäätösten retoriikka [At the Last Judgment. The Rhetoric in the Precedents of the Supreme Court of Finland the European Court of Justice] Helsinki: Lakimiesliiton kustannus.

Höglund & Lee: Purpose of current study to gain an understanding of how the concepts of ’human beings’ and 'morality’ are constructed in biotechnological cases related to human embryos

Data of current case study Case C-34/10, Oliver Brüstle v. Greenpeace e. V, judgment given on 18 th October, 2011. Advocate General Y. Bot; the opinion delivered on 11 th March, 2011. Case C-364/13, the International Stem Cell Corporation v. Comptroller General of Patents, Designs and Trade Marks, given on 18 th December, 2014. Advocate General P. Cruz Villalòn; the opinion delivered on 17 th July, 2014.

Sample chosen for pilot study analysis: AG Cruz Villalón to Case C‐ 364/13 Looking for recurring patterns in the text (as in grounded theory) Rising out of the text: Turning points of the argumentation (Positioning? Rhetorical devices? )

Preliminary findings The text in itself is “objective” Formal use of legal sources BUT the writer speaks with his own voice: authorial voice The writer positions himself

Positioning “I take the floor” 24. I propose to exclude unfertilised human ova whose division and further development have been stimulated by parthenogenesis from the notion of ‘human embryos’ in the sense of [. . . ] 32. [. . . ] I consider it necessary to discuss the meaning and scope of the list of prohibitions of patentability [. . . ] 46. I do not think this is the case.

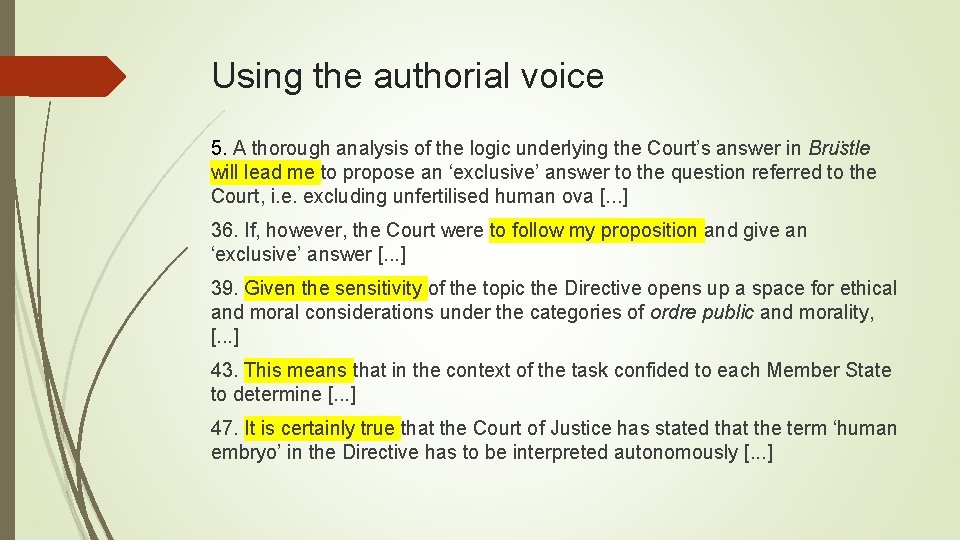

Using the authorial voice 5. A thorough analysis of the logic underlying the Court’s answer in Bru stle will lead me to propose an ‘exclusive’ answer to the question referred to the Court, i. e. excluding unfertilised human ova [. . . ] 36. If, however, the Court were to follow my proposition and give an ‘exclusive’ answer [. . . ] 39. Given the sensitivity of the topic the Directive opens up a space for ethical and moral considerations under the categories of ordre public and morality, [. . . ] 43. This means that in the context of the task confided to each Member State to determine [. . . ] 47. It is certainly true that the Court of Justice has stated that the term ‘human embryo’ in the Directive has to be interpreted autonomously [. . . ]

Fusing legal sources and authorial voice in argumentation 42. Thus, it does not appear to me as though the two paragraphs of Article 6 belong to different worlds, the first to that of ordre public and morality and the second to that of law. On the contrary, Article 6(2) expresses a minimum, Union-wide consensus for all Member States, in legal terms, on which inventions may not be considered patentable on the basis of considerations of ordre public and morality.

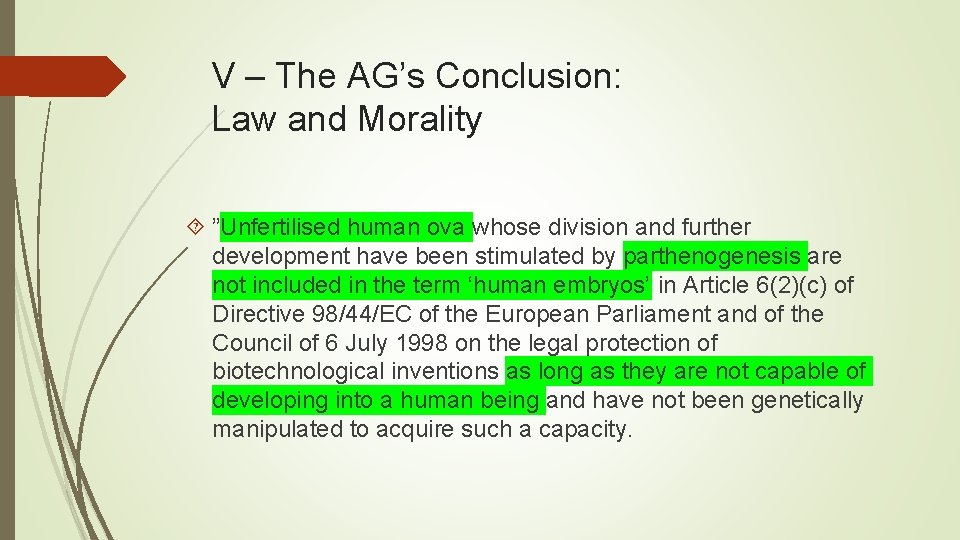

V – The AG’s Conclusion: Law and Morality ”Unfertilised human ova whose division and further development have been stimulated by parthenogenesis are not included in the term ‘human embryos’ in Article 6(2)(c) of Directive 98/44/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 6 July 1998 on the legal protection of biotechnological inventions as long as they are not capable of developing into a human being and have not been genetically manipulated to acquire such a capacity.

Summary: The AG uses the freedom of his position Ø to define morality = law; the concepts are fused Ø to define ‘human embryos’ through 3 functions 1) unfertilised human ova; 2) parthenogenesis; 3) lack of capability to develope into a human being The AG uses legal sources, positioning, and authorial voice to argue & provide definitions for the CJEU

Work in progress… Relationship of AG’s opinion to CJEU judgment in each case? Comparison of the voices of the AGs? Implications of the opinions of the AGs on the understanding of “morality” as promoted by legislation?

Thank you for your attention! Questions?

- Slides: 23