What Does It Mean to be a Female

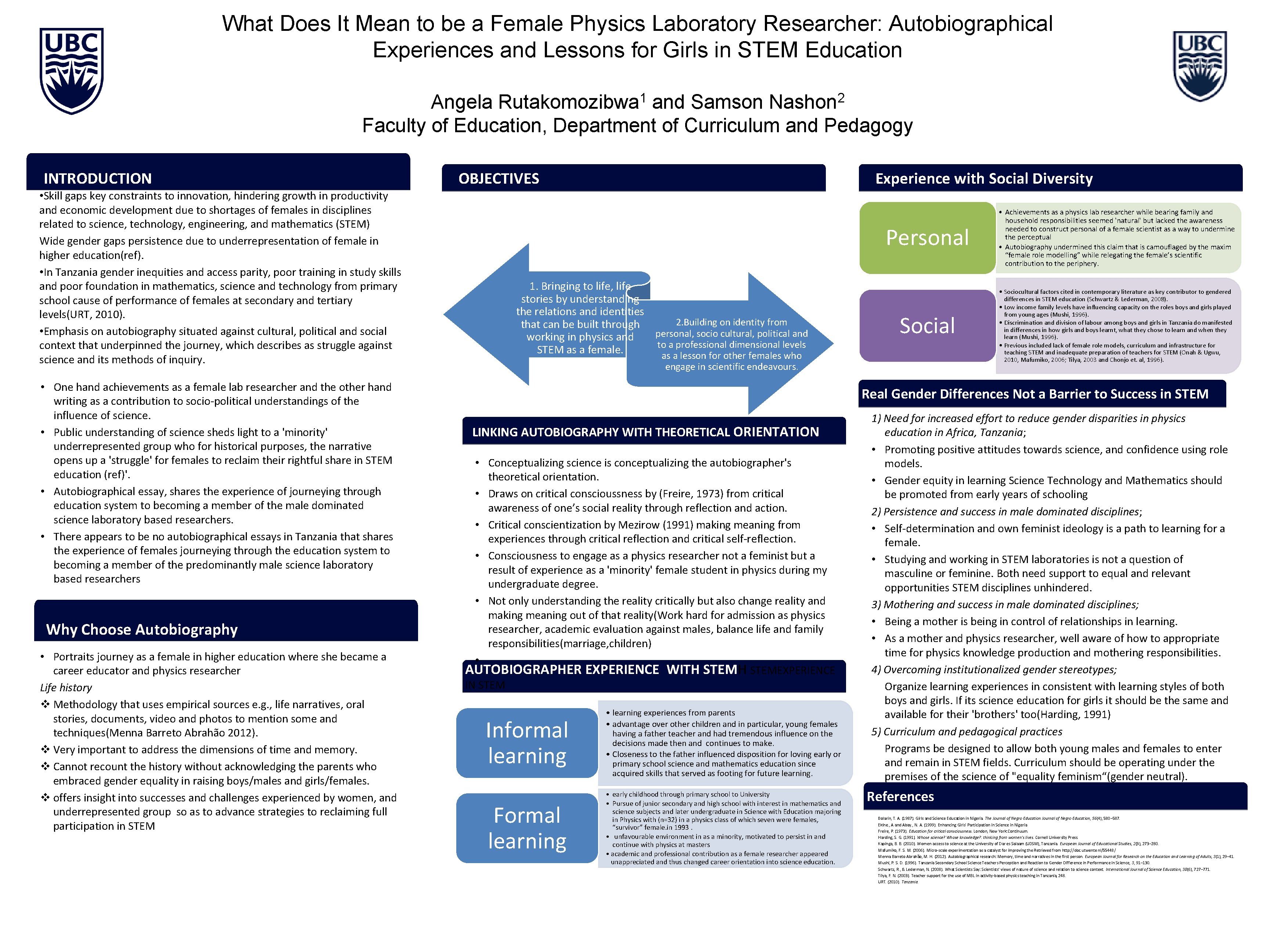

What Does It Mean to be a Female Physics Laboratory Researcher: Autobiographical Experiences and Lessons for Girls in STEM Education 1 Rutakomozibwa Angela and Samson Faculty of Education, Department of Curriculum and Pedagogy INTRODUCTION OBJECTIVES • Skill gaps key constraints to innovation, hindering growth in productivity and economic development due to shortages of females in disciplines related to science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) Wide gender gaps persistence due to underrepresentation of female in higher education(ref). • In Tanzania gender inequities and access parity, poor training in study skills and poor foundation in mathematics, science and technology from primary school cause of performance of females at secondary and tertiary levels(URT, 2010). • Emphasis on autobiography situated against cultural, political and social context that underpinned the journey, which describes as struggle against science and its methods of inquiry. • One hand achievements as a female lab researcher and the other hand writing as a contribution to socio-political understandings of the influence of science. • Public understanding of science sheds light to a 'minority' underrepresented group who for historical purposes, the narrative opens up a 'struggle' for females to reclaim their rightful share in STEM education (ref)'. • Autobiographical essay, shares the experience of journeying through education system to becoming a member of the male dominated science laboratory based researchers. • There appears to be no autobiographical essays in Tanzania that shares the experience of females journeying through the education system to becoming a member of the predominantly male science laboratory based researchers Why Choose Autobiography • Portraits journey as a female in higher education where she became a career educator and physics researcher Life history v Methodology that uses empirical sources e. g. , life narratives, oral stories, documents, video and photos to mention some and techniques(Menna Barreto Abrahão 2012). v Very important to address the dimensions of time and memory. v Cannot recount the history without acknowledging the parents who embraced gender equality in raising boys/males and girls/females. v offers insight into successes and challenges experienced by women, and underrepresented group so as to advance strategies to reclaiming full participation in STEM 2 Nashon Experience with Social Diversity 1. Bringing to life, life stories by understanding the relations and identities 2. Building on identity from that can be built through personal, socio cultural, political and working in physics and to a professional dimensional levels STEM as a female. as a lesson for other females who Personal • Achievements as a physics lab researcher while bearing family and household responsibilities seemed 'natural' but lacked the awareness needed to construct personal of a female scientist as a way to undermine the perceptual • Autobiography undermined this claim that is camouflaged by the maxim “female role modelling” while relegating the female’s scientific contribution to the periphery. Social • Sociocultural factors cited in contemporary literature as key contributor to gendered differences in STEM education (Schwartz & Lederman, 2008). • Low income family levels have influencing capacity on the roles boys and girls played from young ages (Mushi, 1996). • Discrimination and division of labour among boys and girls in Tanzania do manifested in differences in how girls and boys learnt, what they chose to learn and when they learn (Mushi, 1996). • Previous included lack of female role models, curriculum and infrastructure for teaching STEM and inadequate preparation of teachers for STEM (Onah & Ugwu, 2010, Mafumiko, 2006; Tilya, 2003 and Chonjo et. al, 1996). engage in scientific endeavours. Real Gender Differences Not a Barrier to Success in STEM LINKING AUTOBIOGRAPHY WITH THEORETICAL ORIENTATION • Conceptualizing science is conceptualizing the autobiographer's theoretical orientation. • Draws on critical conscioussness by (Freire, 1973) from critical awareness of one’s social reality through reflection and action. • Critical conscientization by Mezirow (1991) making meaning from experiences through critical reflection and critical self-reflection. • Consciousness to engage as a physics researcher not a feminist but a result of experience as a 'minority' female student in physics during my undergraduate degree. • Not only understanding the reality critically but also change reality and making meaning out of that reality(Work hard for admission as physics researcher, academic evaluation against males, balance life and family responsibilities(marriage, children) • AUTOBIOGRAPHER EXPERIENCE WITH STEMEXPERIENCE IN STEM. Informal learning • learning experiences from parents • advantage over other children and in particular, young females having a father teacher and had tremendous influence on the decisions made then and continues to make. • Closeness to the father influenced disposition for loving early or primary school science and mathematics education since acquired skills that served as footing for future learning. Formal learning • early childhood through primary school to University • Pursue of junior secondary and high school with interest in mathematics and science subjects and later undergraduate in Science with Education majoring in Physics with (n=32) in a physics class of which seven were females, “survivor” female. in 1993. • unfavourable environment in as a minority, motivated to persist in and continue with physics at masters • academic and professional contribution as a female researcher appeared unappreciated and thus changed career orientation into science education. 1) Need for increased effort to reduce gender disparities in physics education in Africa, Tanzania; • Promoting positive attitudes towards science, and confidence using role models. • Gender equity in learning Science Technology and Mathematics should be promoted from early years of schooling 2) Persistence and success in male dominated disciplines; • Self-determination and own feminist ideology is a path to learning for a female. • Studying and working in STEM laboratories is not a question of REFERENCES masculine or feminine. Both need support to equal and relevant opportunities STEM disciplines unhindered. 3) Mothering and success in male dominated disciplines; • Being a mother is being in control of relationships in learning. • As a mother and physics researcher, well aware of how to appropriate time for physics knowledge production and mothering responsibilities. 4) Overcoming institutionalized gender stereotypes; Organize learning experiences in consistent with learning styles of both boys and girls. If its science education for girls it should be the same and available for their 'brothers' too(Harding, 1991) 5) Curriculum and pedagogical practices Programs be designed to allow both young males and females to enter and remain in STEM fields. Curriculum should be operating under the premises of the science of "equality feminism“(gender neutral). References Bolarin, T. A. (1987). Girls and Science Education in Nigeria. The Journal of Negro Education, 56(4), 580– 587. Ekine. , A and Abay. , N. A. (1999). Enhancing Girls’ Participation in Science in Nigeria. Freire, P. (1973). Education for critical consciousness. London, New York: Continuum. Harding, S. G. (1991). Whose science? Whose knowledge? : thinking from women’s lives. Cornell University Press. Kapinga, B. B. (2010). Women access to science at the University of Dar es Salaam (UDSM), Tanzania. European Journal of Educational Studies, 2(3), 273– 280. Mafumiko, F. S. M. (2006). Micro-scale experimentation as a catalyst for improving the Retrieved from http: //doc. utwente. nl/55448/ Menna Barreto Abrahão, M. H. (2012). Autobiographical research: Memory, time and narratives in the first person. European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults, 3(1), 29– 41. Mushi, P. S. D. (1996). Tanzania Secondary School Science Teachers Perception and Reaction to Gender Difference in Performance in Science, 3, 91– 130. Schwartz, R. , & Lederman, N. (2008). What Scientists Say: Scientists’ views of nature of science and relation to science context. International Journal of Science Education, 30(6), 727– 771. Tilya, F. N. (2003). Teacher support for the use of MBL in activity-based physics teaching in Tanzania, 248. URT. (2010). Tanzania.

- Slides: 1