Week 6 Golden Age II Dorothy L Sayers

- Slides: 10

Week 6: Golden Age II Dorothy L. Sayers Gaudy Night (1935)

Dorothy Leigh Sayers (1893 -1957) • Born 1893 in Oxford. Her father was headteacher of Christ Church Cathedral school. The family later moved to Cambridge. She was educated at home and then at Godolphin School, Salisbury. • Sayers won a scholarship to study medieval and modern languages at Somerville College, Oxford. In 1915 she finished with first-class honours (and was later awarded a degree). • After her studies, Sayers worked for the publisher Blackwell’s. From 1922 -29, she was a copywriter for the London advertising firm Benson’s. • In 1926 she married journalist Oswald Atherton Fleming. She’d already had a child with Bill White, a car salesman. The son was cared for by her aunt and cousin and passed off as her nephew. • In 1923, she published her first novel, Whose Body? , which introduced the aristocratic sleuth Lord Peter Wimsey. He would go on to feature in 14 volumes of novels and short stories. Harriet Vane first appeared in Strong Poison (1930). • Sayers was President of the Detection Club from 1949 -57. • A prolific writer – she was also a poet, playwright, essayist, translator, and Christian humanist (she was Anglican). Well-known for her radio drama, The Man Born to be King (1941 -2). She considered her translation of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1949) to be her best work. • She died from heart failure in 1957, still writing.

Gaudy Night (1935) • Tenth novel featuring Lord Peter Wimsey, and third featuring Harriet Vane. • Shift in tone: first story told from Harriet’s own perspective. • More psychological realism. • Set in the fictional Shrewsbury College – based on Sayers’s own experiences at Somerville. • Secluded, cloistered environment – trying to contain a scandal. • Engages with prejudice surrounding women’s education – • fears about how the incidents might undermine the cause; • stereotypes of unmarried, educated women. • Theme: conflicts between academic integrity/ intellectual life and personal relationships. • Hugely popular – sold out first edition upon publication. Drew mixed critical reviews. • Tension in Sayers’s career: popular fiction vs. serious literature.

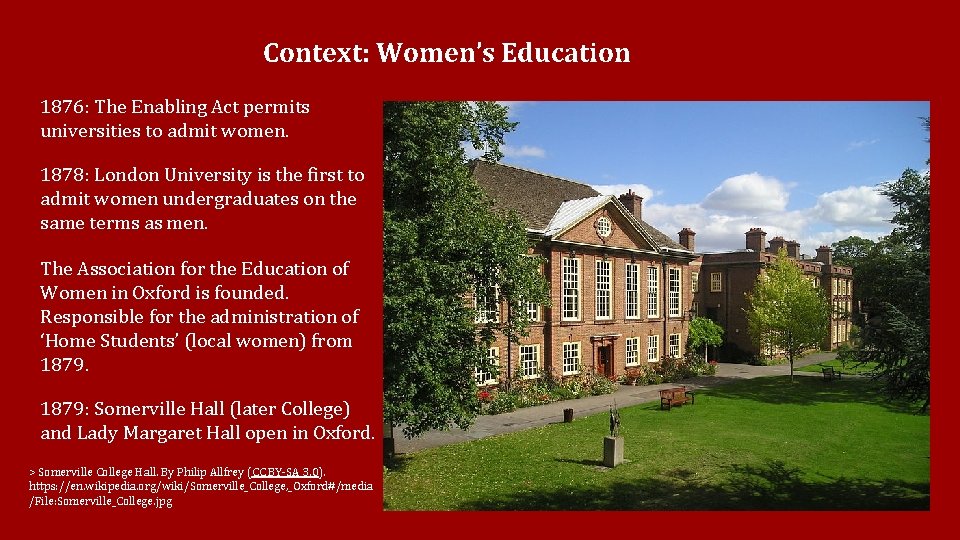

Context: Women’s Education 1876: The Enabling Act permits universities to admit women. 1878: London University is the first to admit women undergraduates on the same terms as men. The Association for the Education of Women in Oxford is founded. Responsible for the administration of ‘Home Students’ (local women) from 1879: Somerville Hall (later College) and Lady Margaret Hall open in Oxford. > Somerville College Hall. By Philip Allfrey (CC BY-SA 3. 0). https: //en. wikipedia. org/wiki/Somerville_College, _Oxford#/media /File: Somerville_College. jpg

Context: Women’s Education 1881: Women are allowed to sit the Cambridge Tripos (but not to graduate officially). 1880 s: Universities such as Nottingham and Bristol become co-educational. 1884: Oxford degree examinations are opened to women (but no certificate for those who pass). 1886: St Hugh’s College, Oxford founded. 1893: St Hilda’s College, Oxford opens. 1908: Edith Morley (Reading) becomes the first woman university professor in England. 1919: The Sex Disqualification Removal Act. 1920: Women are awarded degrees at Oxford. 1948: Women students at Cambridge are officially allowed to graduate. 1959: The five women’s ‘societies’ (Somerville, Lady Margaret Hall, St Hugh’s, St Hilda’s, and St Anne’s) become full members of the University of Oxford.

Golden Age and Fair Play: The Rules From S. S. Van Dine, ‘Twenty Rules for Writing Detective Stories’, The American Magazine (Sept 1928) > ‘There must be no love interest in the story. ’ Structured around the Harriet Vane – Peter Wimsey relationship. > ‘There simply must be a corpse in a detective novel… No lesser crime than murder will suffice. ’ A series of Poison Pen letters and vicious pranks – but perpetrator progresses to pushing a student to commit suicide and a physical attack. Implication: could end in murder. > ‘There must be but one detective…’ Harriet as the protagonist and narrator but Wimsey as the genius figure? > ‘Servants […] must not be chosen by the author as the culprit. ’ Annie the Scout: both insider/outsider figure? > ‘A detective novel should contain no long descriptive passages, no literary dallying with side issues, no subtly worked-out character analyses, and no “atmospheric” preoccupations. ’ Literary qualities of the novel – epigraphs, intertextuality. > ‘The motives for all the crimes in detective stories should be personal. ’ Annie’s personal vendetta: expands from Miss de Vine to the proponents of women’s education more generally.

Psychological Realism ‘these chapters convey more real eeriness and discomfort than you could get from gallons of blood. ’ - Dorothy L. Sayers, The Sunday Times, 16 July 1933. ‘Some readers prefer their detective stories to be of […] [the] conventional kind; they like to enjoy the surface excitement without the inward disturbance that comes of being forced to take things seriously. But I believe the future to be with those writers who can contrive to strike the note of sincerity and to persuade us that violence really hurts. ’ - Dorothy L. Sayers, The Sunday Times, 26 May 1935.

Psychological Realism ‘In Gaudy Night, she finally accomplishes her goal of marrying the detective plot to the English novel […] Gaudy Night is a mystery story, but in it, the focus is upon the human perplexities revealed through the mystery, rather than upon the detective problem per se. Thus, the novel raises more questions than it answers, and troubles the reader into thinking about real human problems and real human life. ’ - Catherine Kenney, The Remarkable Case of Dorothy L. Sayers (London: Kent State University Press, 1990), p. 81.

Critical Reception: Feminism ‘Gaudy Night is a wonderful feminist mystery and still an inspiration to women writing today. But I do not see feminism as the heart and soul of Gaudy Night. Important, integral, visionary, but not the heart and soul of that novel. The heart and soul of Gaudy Night is the importance of scholarship, which is, when all is said and done, the impartial search for the truth. ’ - Carolyn G. Hart, ‘Gaudy Night: Quintessential Sayers’, in Dorothy L. Sayers: The Centenary Celebration, ed. by Alzina Stone Dale (Lincoln: Walker, 1993).

Critical Reception: Feminism ‘either Gaudy Night is a successful feminist novel or it is woefully complicit with conservative gender ideology […] I argue the novel is both. ’ ‘Rather than providing an idealistic view of women in higher education and the possibilities that await them, Dorothy L. Sayers’s Gaudy Night provides a much more daunting, subtle view of the way societal expectations invade even the best intentions. ’ - Ann Mc. Clellan, ‘Alma Mater: Women, The Academy, and Mothering in Dorothy L. Sayers’s Gaudy Night’, Literature Interpretation Theory, 15 (2004): 321 -46 (p. 321, 340).

Sayers v harlow

Sayers v harlow Pete sayers

Pete sayers Iron age bronze age stone age timeline

Iron age bronze age stone age timeline Iron age bronze age stone age timeline

Iron age bronze age stone age timeline Week by week plans for documenting children's development

Week by week plans for documenting children's development Golden ratio the sacrament of the last supper

Golden ratio the sacrament of the last supper Modified fibonacci sequence

Modified fibonacci sequence The golden ratio in russian poetry

The golden ratio in russian poetry Weimar golden age

Weimar golden age Golden age of hollywood 1930s

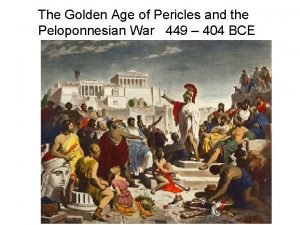

Golden age of hollywood 1930s Peloponnesian war

Peloponnesian war