WEEK 5 WOMEN IN THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION TEXTILES

- Slides: 24

WEEK 5 WOMEN IN THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION – TEXTILES frances. richardson@conted. ox. ac. uk http: //open. conted. ox. ac. uk/series/womans-work-never-donewomens-work-england-wales-1600 -1914

Week 4 key points on proto-industry • Take-off in 18 c due to growing consumer society, home market and exports • Typically started as part of household economy as a by-employment, but increasingly undertaken by the labouring poor • Enabled married women to make a vital contribution to family living standards at a time when women’s casual work in agriculture decreasing • Hand spinning the biggest women’s manufacture over most of the country – decline due to mechanisation brought immense hardship to many families • Women worked for husband in some proto-industries, e. g. framework knitting • Usually low paid and insecure. Below-subsistence earnings assumed women’s earnings an adjunct to male wage • Decline between 1770 s and 1870 s due to mechanisation, foreign competition, changes in fashion

Women in the Industrial Revolution Textiles - key themes • Considerable debate about whether the Industrial Revolution had a positive or negative impact on women’s employment and wages • Cotton the first industrializes sector • Why employ women and girls? • Changes to the gender division of labour – men’s influence • Regional differences and de-industrialisation

DISCUSSION 1. What do we learn from Sir Edward Baines’ History of the Cotton Manufacture in Great Britain about the type of work, wages, and conditions of women working in cotton factories in 1835? OR 2. How have historians explained the changing gender division of labour with the transition to factory production of cotton?

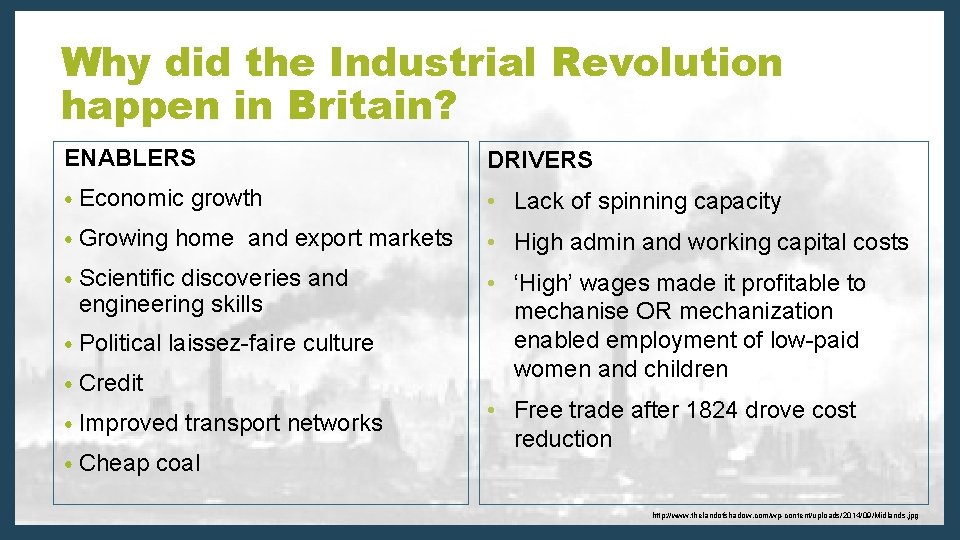

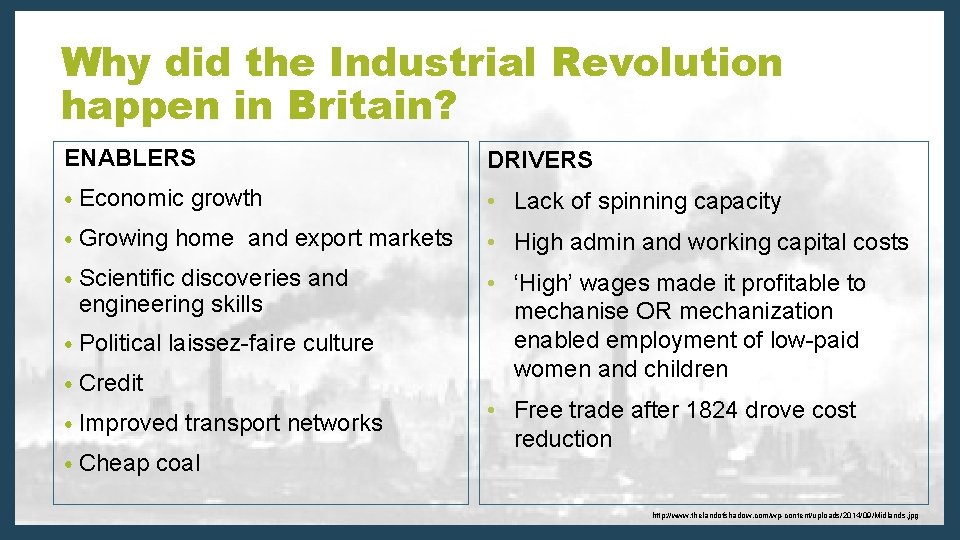

Why did the Industrial Revolution happen in Britain? ENABLERS DRIVERS • Economic growth • Lack of spinning capacity • Growing home and export markets • High admin and working capital costs • Scientific discoveries and • ‘High’ wages made it profitable to mechanise OR mechanization enabled employment of low-paid women and children engineering skills • Political laissez-faire culture • Credit • Improved transport networks • Cheap coal • Free trade after 1824 drove cost reduction http: //www. thelandofshadow. com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Midlands. jpg

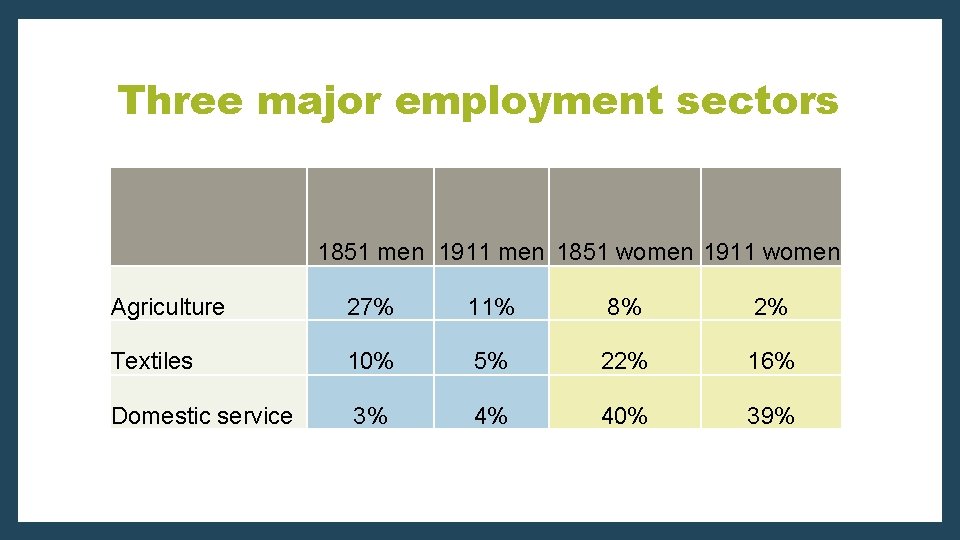

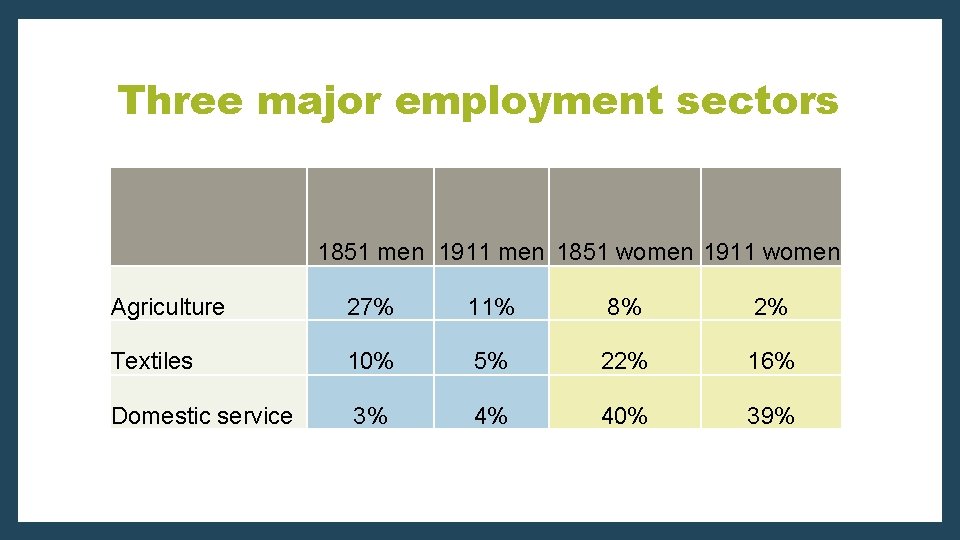

Three major employment sectors 1851 men 1911 men 1851 women 1911 women Agriculture 27% 11% 8% 2% Textiles 10% 5% 22% 16% Domestic service 3% 4% 40% 39%

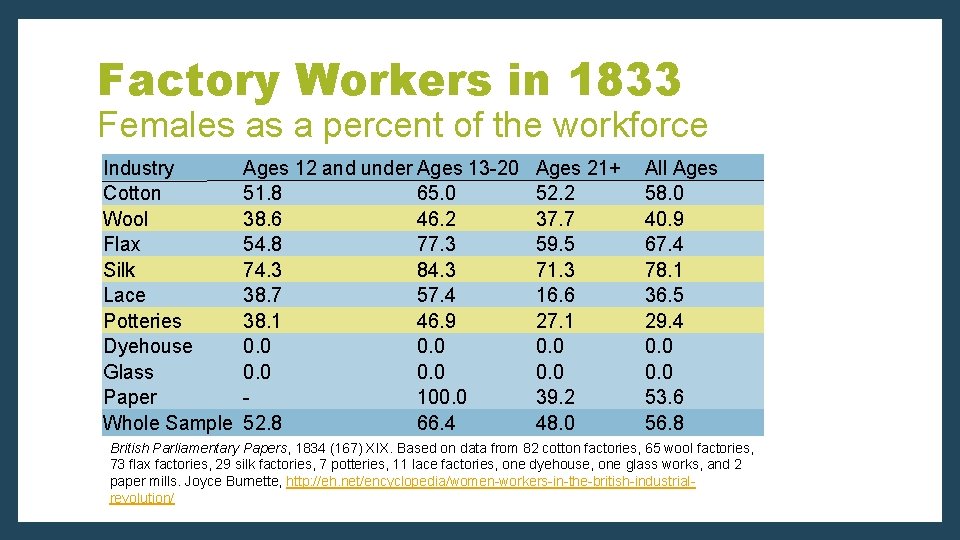

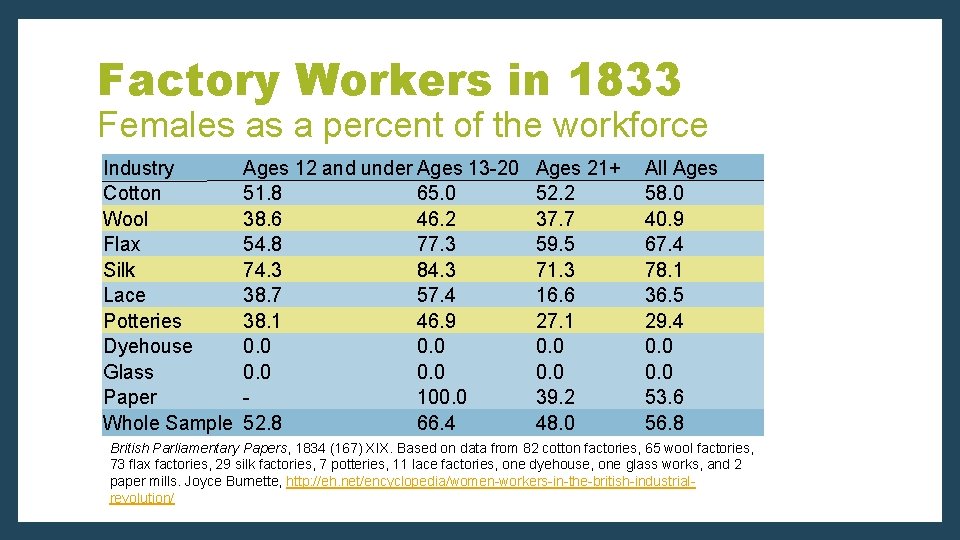

Factory Workers in 1833 Females as a percent of the workforce Industry Cotton Wool Flax Silk Lace Potteries Dyehouse Glass Paper Whole Sample Ages 12 and under Ages 13 -20 51. 8 65. 0 38. 6 46. 2 54. 8 77. 3 74. 3 84. 3 38. 7 57. 4 38. 1 46. 9 0. 0 100. 0 52. 8 66. 4 Ages 21+ 52. 2 37. 7 59. 5 71. 3 16. 6 27. 1 0. 0 39. 2 48. 0 All Ages 58. 0 40. 9 67. 4 78. 1 36. 5 29. 4 0. 0 53. 6 56. 8 British Parliamentary Papers, 1834 (167) XIX. Based on data from 82 cotton factories, 65 wool factories, 73 flax factories, 29 silk factories, 7 potteries, 11 lace factories, one dyehouse, one glass works, and 2 paper mills. Joyce Burnette, http: //eh. net/encyclopedia/women-workers-in-the-british-industrialrevolution/

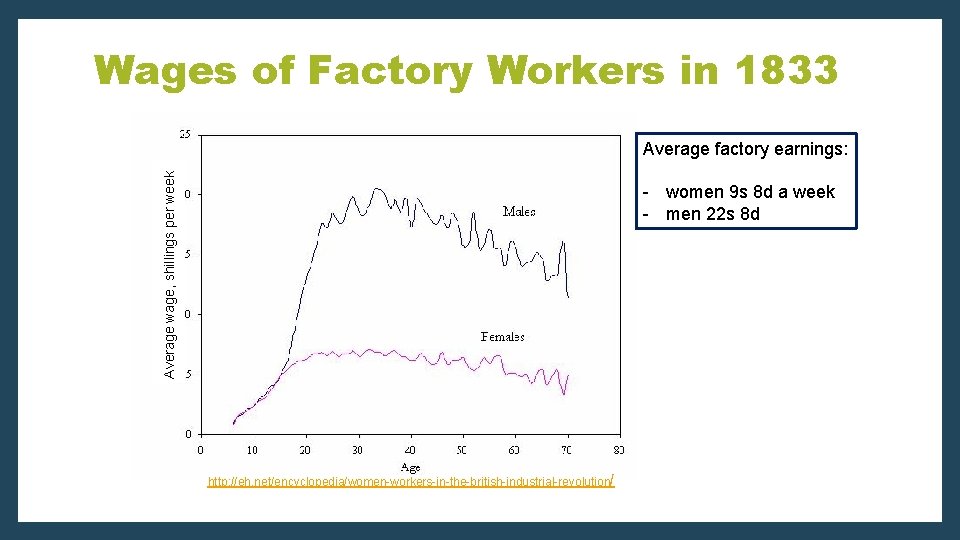

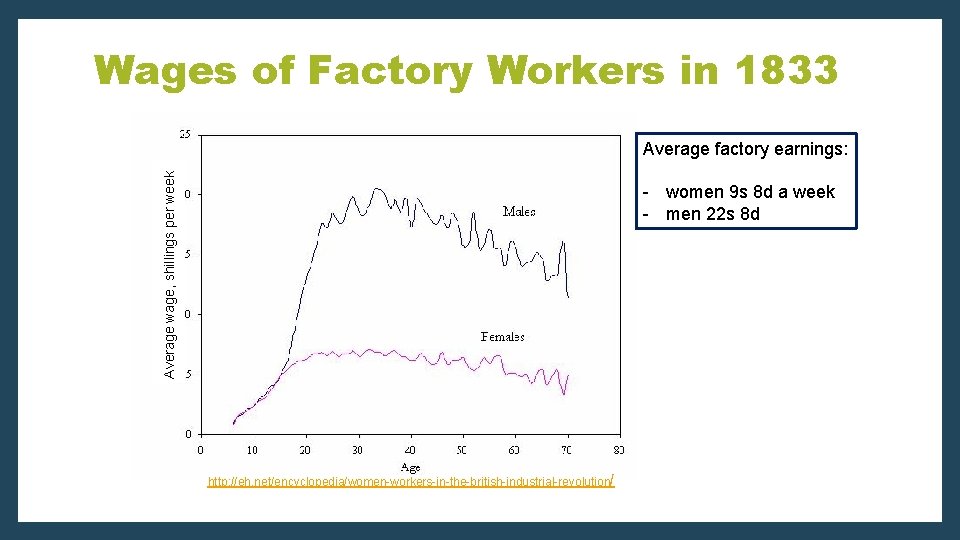

Wages of Factory Workers in 1833 Average wage, shillings per week Average factory earnings: - women 9 s 8 d a week - men 22 s 8 d http: //eh. net/encyclopedia/women-workers-in-the-british-industrial-revolution/

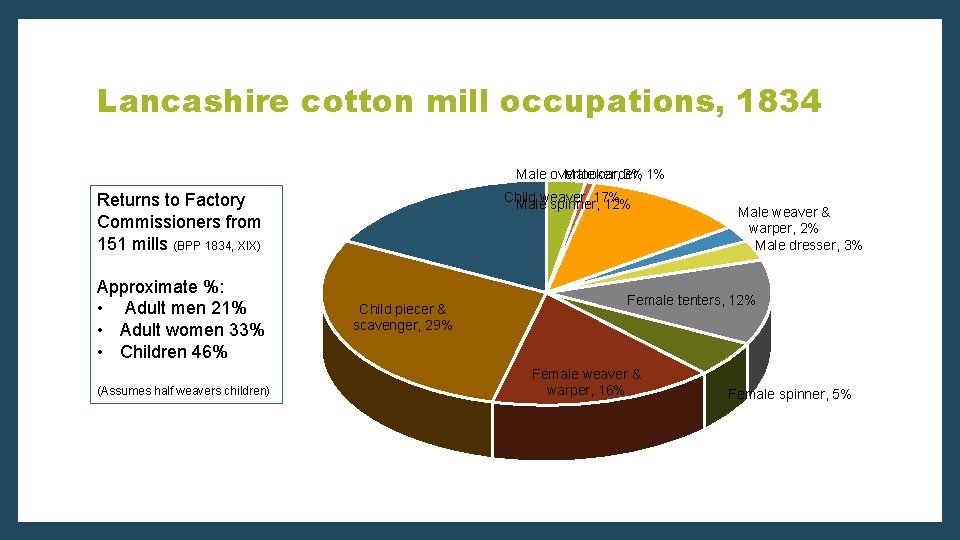

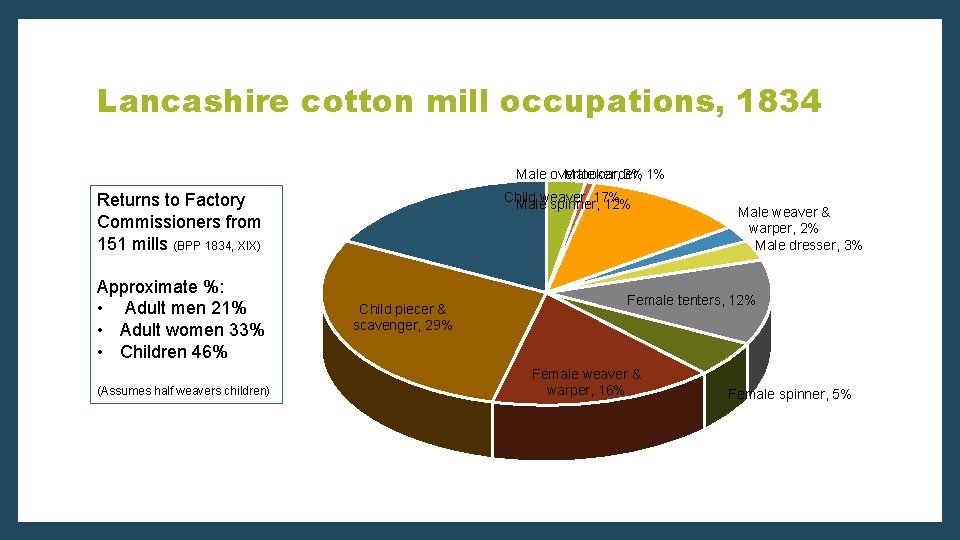

Lancashire cotton mill occupations, 1834 Male overlooker, 3% Male carder, 1% Child weaver, 17% Male spinner, 12% Returns to Factory Commissioners from 151 mills (BPP 1834, XIX) Approximate %: • Adult men 21% • Adult women 33% • Children 46% (Assumes half weavers children) Child piecer & scavenger, 29% Male weaver & warper, 2% Male dresser, 3% Female tenters, 12% Female weaver & warper, 16% Female spinner, 5%

Technological change – cotton carding and spinning Proto-industrial production: • Picking over cotton to remove seeds using hand gin • Hand carding, spinning twice, into rovings, then yarn Early mechanisation: • 1770 s – Hargreaves’ spinning jenny bought by spinners, enabled women to spin multiple yarn threads. Carding and roving still done by hand • 1780 s - larger jennies introduced in workshops, more likely operated by men • Crompton’s mule added rollers to jenny, spun finer thread – initially small enough for domestic putting-out system, but more expensive

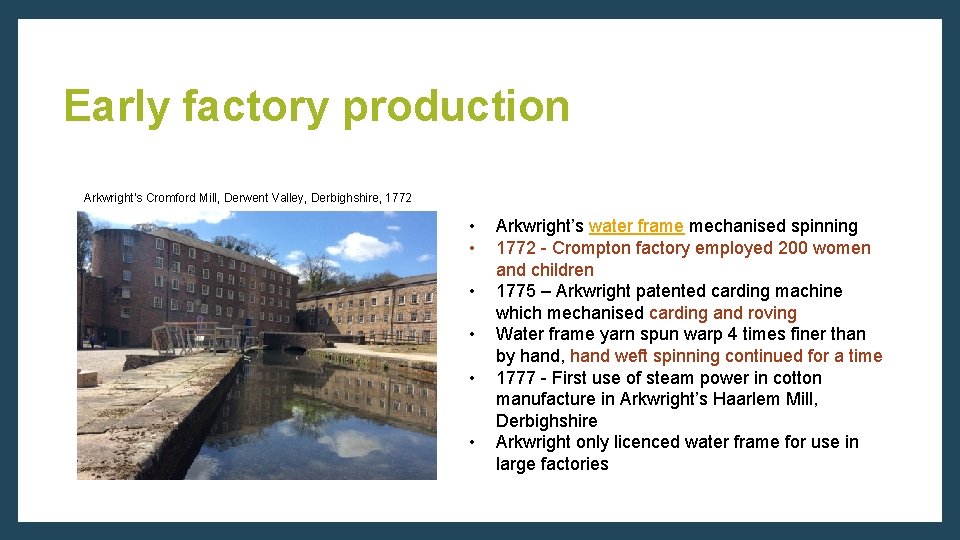

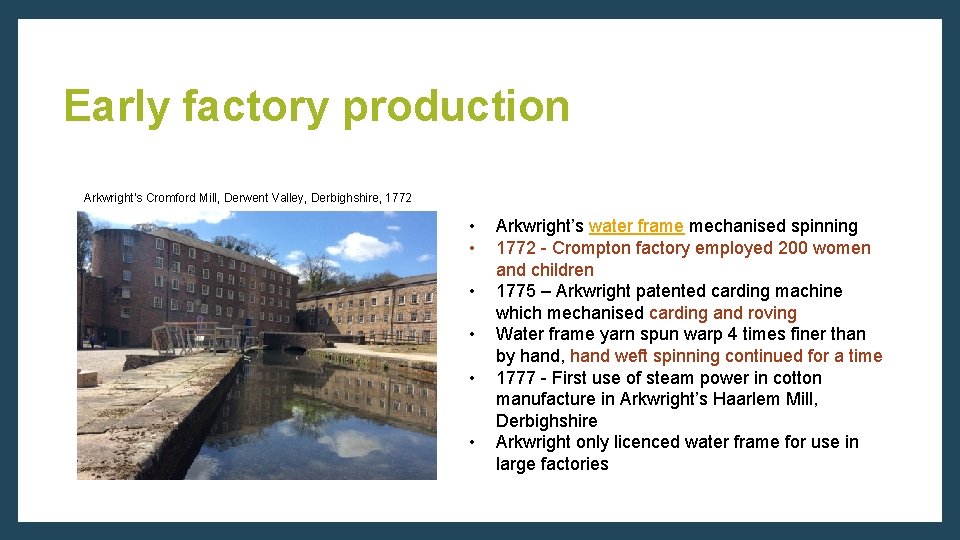

Early factory production Arkwright’s Cromford Mill, Derwent Valley, Derbighshire, 1772 • • • Arkwright’s water frame mechanised spinning 1772 - Crompton factory employed 200 women and children 1775 – Arkwright patented carding machine which mechanised carding and roving Water frame yarn spun warp 4 times finer than by hand, hand weft spinning continued for a time 1777 - First use of steam power in cotton manufacture in Arkwright’s Haarlem Mill, Derbighshire Arkwright only licenced water frame for use in large factories

Factory production – mule spinning • Factory communities in rural locations to attract women • Girl apprentices, often from workhouse • Larger mules initially heavy – became men’s work • 1790 s - when mechanised using water power, often remained well paid men’s work • Steam driven from late 1790 s All pictures www. nationaltrust. org. uk/quarry-bank Workers’ cottages, Styal Quarry Bank Mill, Cheshire

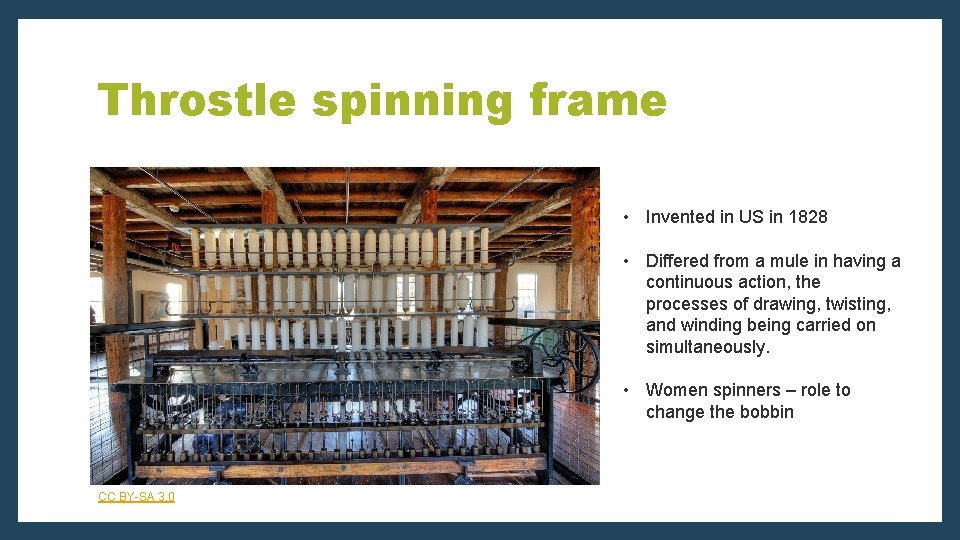

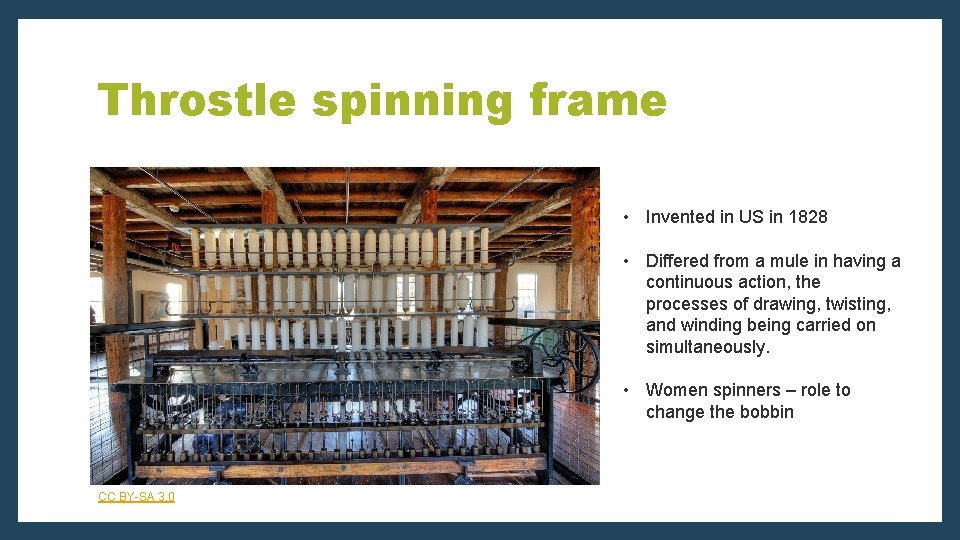

Throstle spinning frame • Invented in US in 1828 • Differed from a mule in having a continuous action, the processes of drawing, twisting, and winding being carried on simultaneously. • Women spinners – role to change the bobbin CC BY-SA 3. 0

Calico printing • English printers perfected techniques of designing, engraving and colouring printed textiles after 1750 • Served both quality and mass market, expanded demand for cotton • Hand-block printing and pencilling done by women • Cylinder printing introduced 1785 • One man and a boy could do the work of 100 hand-printers • By 1835, 75% of cotton printed by machine Cylinder printer from Baines, History of Cotton Manufacturing (1835)

Weaving • Weaving traditionally a male role, but could be assisted by wife, e. g. on broad loom • Breakdown of apprenticeship in late 18 c • Mechanisation of spinning created demand for extra weavers • Rapid increase in women weavers replacing lost spinning work - 40% in some areas by 1800 • Women mainly produced lighter fabrics such as muslin, worsted and flannel • Power loom invented in 1785, but not widely used till improved in late 1820 s Clem Rutter, Rochester, Kent CC BY 3. 0 F W Jackson - Manchester Art Gallery, CC BY-SA 3. 0

The plight of the handloom weavers • Wages fell progressively after 1815, even before widespread use of power loom • Even with whole family working, wages below subsistence, had to be supplemented by poor relief in 1820 s • Yorkshire weavers tramped 8 miles carrying their bales of cloth to sell in Huddersfield. After working a 12 -14 hour day, they earned 5 s a week, and generally lived on porridge and potatoes. (1834) • Families responded by working longer hours, setting younger children to work. • Where possible, women weavers went into factories and became power loom weavers ‘It is truly lamentable to behold so many thousands of men who formerly earned 20 to 30 shillings per week, now compelled to live upon 5 s, 4 s, or even less. ’ William Cobbett, 1832

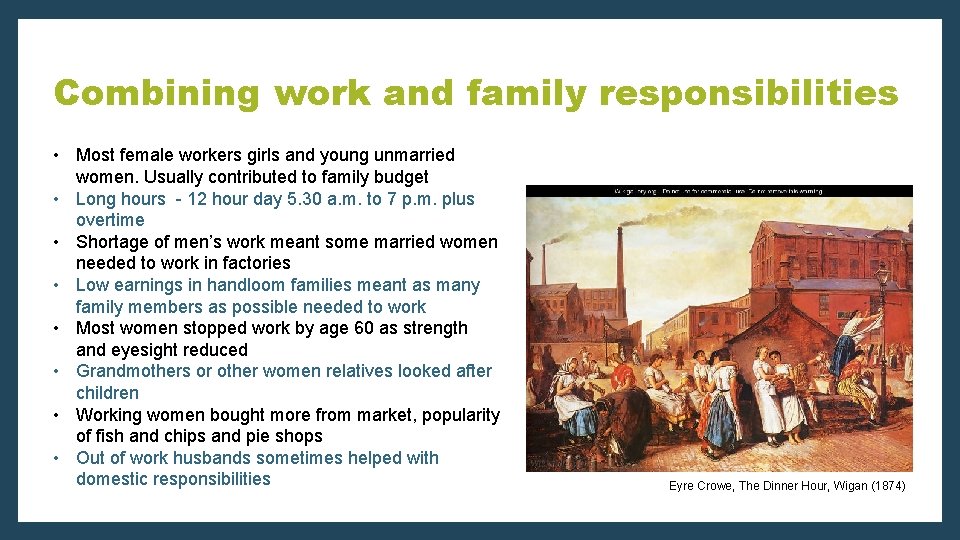

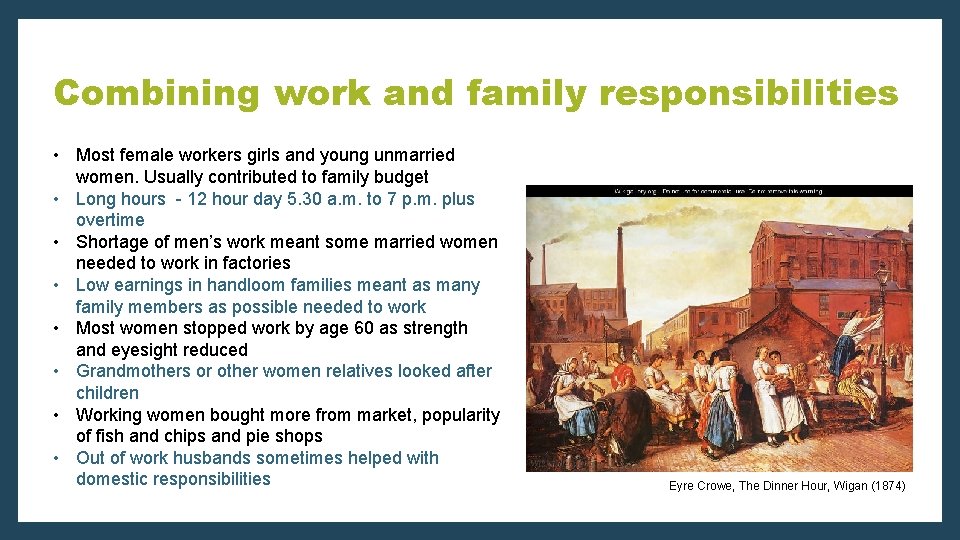

Combining work and family responsibilities • Most female workers girls and young unmarried women. Usually contributed to family budget • Long hours - 12 hour day 5. 30 a. m. to 7 p. m. plus overtime • Shortage of men’s work meant some married women needed to work in factories • Low earnings in handloom families meant as many family members as possible needed to work • Most women stopped work by age 60 as strength and eyesight reduced • Grandmothers or other women relatives looked after children • Working women bought more from market, popularity of fish and chips and pie shops • Out of work husbands sometimes helped with domestic responsibilities Eyre Crowe, The Dinner Hour, Wigan (1874)

Increased gender division of labour • Strength sometimes a factor, but often not • Repeal of Statute of Artificers in 1814 did away with requirement for apprenticeship • Employers hired women (and children) when cheaper • Male workers reluctant to do same jobs as women due to threat of lower pay • Male trade unionists excluded women from better-paid or more skilled roles • Women rarely employed in supervisory positions • Women moved into low-paid low-tech work such as handloom weaving, then power-loom weaving

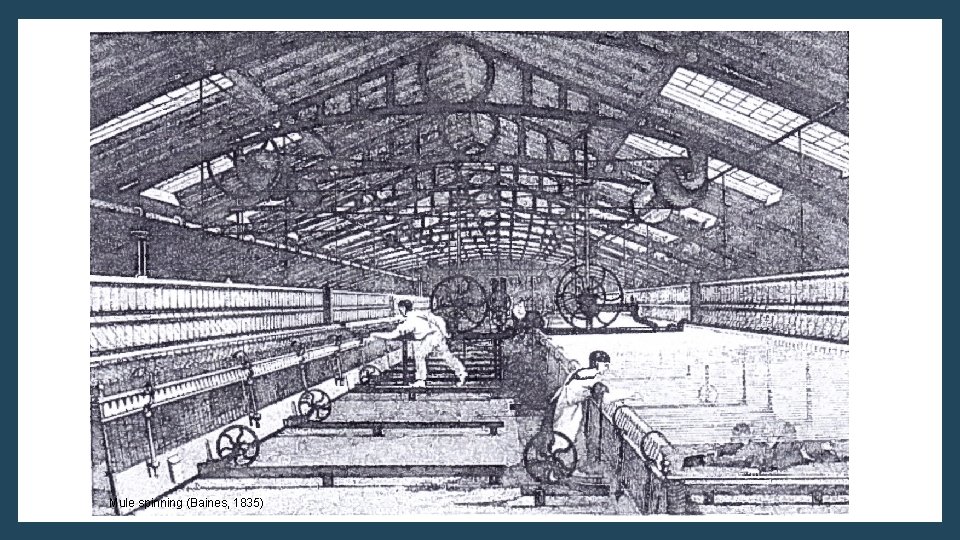

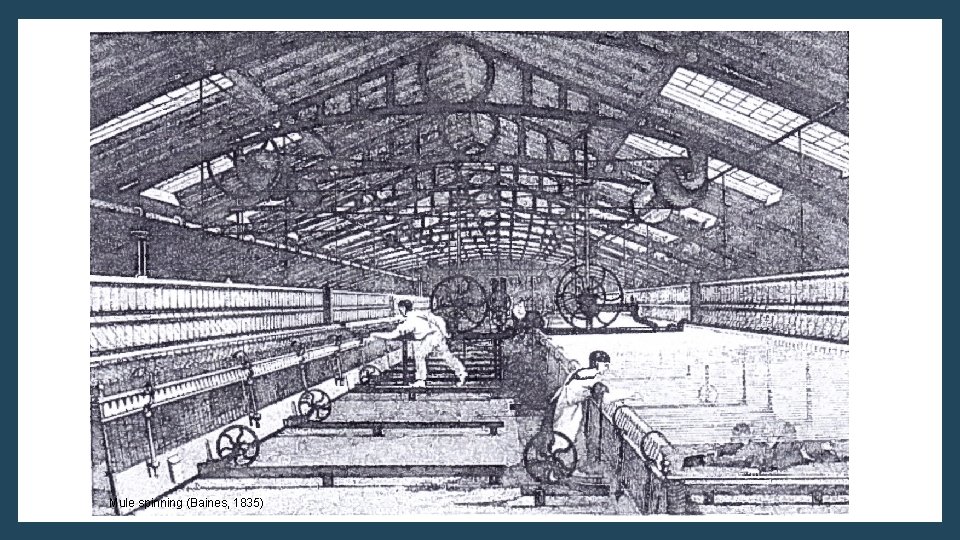

Men’s attempts to exclude women • Before mid-18 c, 7 year apprenticeship restricted entry to weaving • Weaving apprenticeship broke down late 18 c • Attempts by male craft workers in early 1800 s to defend their ‘property in skill’ by strikes, Parliamentary petitions and direct action failed due to: laissez-faire economic philosophy - middle class view that poor women’s work was virtuous and necessary - • Men in new industrial roles imported view of skilled status, defended against dilution by women – mechanics, mule spinners, cylinder printers, wool finishers • No case made for male breadwinner’s family wage in 1830 s Mule spinning (Baines, 1835)

Social attitudes to mill girls • Growth of domestic ideology among middle class by 1830 s - horrified fascination with mill girl • Pity for their long hours, unpleasant working conditions • Concern at breakdown of patriarchal family order – young women living in lodgings, dressing well • Moral condemnation for their scanty clothing, selfconfidence, course language, immodest behaviour including walking home at night • Belief that mill girls made bad housewives • Some commentators justified women’s low wages because it gave them less temptation to abandon the care of their offspring and homes • Reformers concentrated on reducing women’s hours, not increasing their pay

DISCUSSION Why did women in cotton factories earn so much less than men and why did they accept this?

Why did women accept lower factory wages? • 1833 factory report found men’s wages nearly 2 ½ times women’s • Factory wages good compared to other types of women’s work • Lack of alternative work after decline of hand spinning and reduced opportunities in agriculture • Regular employment • Not usually the family’s main breadwinner • Gave young women some spending money for better food and clothes • No support from male trade unionists or middle-class reformers

Summary - impact of textile industrialization on women • Expanded employment in major textile districts e. g. Lancashire and Yorkshire • Better paid than most other women’s work, but only 30% of men’s wage – women confined to low-skill, low-paid work • Difficult to combine with family responsibilities – married women less likely to work • Declining work in textile districts that failed to modernise and remain competitive – west country, Norwich, north Wales • Loss of hand spinning had a devastating impact on living standards for large proportion of working families • Lack of work for spinsters drove major expansion of domestic service • Widows and unmarried mothers found it even more difficult to support their children

Prep for Week 6 How did industrialization affect the gender division of labour in: the Birmingham metal trades or toy industry • *Ivy Pinchbeck, Women Workers and the Industrial Revolution 1750 -1850 (1930), Chapter XI, Metal trades. (Online in Resources room or Continuing Education Library - http: //solo. bodleian. ox. ac. uk/), 2 hard copies in Continuing Education Library. 2 class loan copies. ) • *Maxine Berg, The Age of Manufactures 1700 -1820, Chapter 12, ’The Birmingham toy trades’. (2 copies in Continuing Education Library. One copy for class loan) • AND/OR the Staffordshire pottery industry • R. Whipp, 'Women and the social organisation of work in the Staffordshire pottery industry, 1900 -1930', Midland History 12 (1987), pp. 103 -121. (Online in Resources room or Continuing Education Library - http: //solo. bodleian. ox. ac. uk/. ) • Marguerite Dupree, ‘Women as wives and workers in the Staffordshire potteries in the nineteenth century’, in N. Goose (ed. ), Women’s Work in Industrial England (Hertfordshire, 2007) (Conted. Library, 1 class loan copy) AND/OR the Midlands hosiery industry? • Nancy Grey Osterud, ‘'Gender divisions and the organisation of work in the Leicester hosiery industry', in A. V. John (ed. ), Unequal Opportunities: Women's Employment in England 1800 -1918 (Oxford, 1986). (In Continuing Education Library. 2 class loan copies).