Web Graphics WWW uses graphical info as well

Web Graphics · WWW uses graphical info as well as text. · We have already seen how to incorporate images into HTML. · This lecture looks at some of the issues in more detail. - graphics file formats - the RGB colour model - colour depth and resolution - the PPM format - compression - web graphics formats - GIF and JPEG - transparent and interlaced gifs - problems with colour - image processing © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 1

Types of Graphics File Formats · A graphics (or image) file format is a standardized convention for storing graphics as files. · These files formats fall into a number of different categories. · The choice of which category you use depends on the nature of the graphics you are interested in and the capabilities of the software which you will use to create/modify/view the images. · Categories - Raster - Vector - 3 D · Raster (or bitmap) formats store images in terms of pixels. In their simplest form, they can store monochrome images in terms of a 2 dimensional grid of squares, each of which can be coloured in black or white. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 2

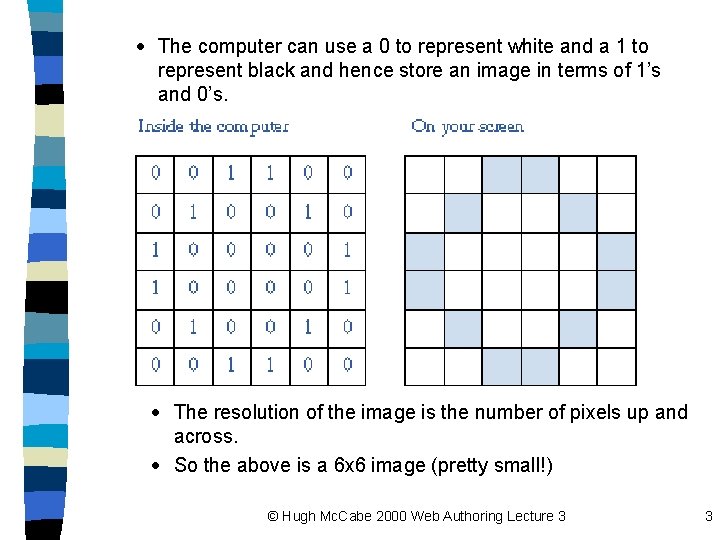

· The computer can use a 0 to represent white and a 1 to represent black and hence store an image in terms of 1’s and 0’s. · The resolution of the image is the number of pixels up and across. · So the above is a 6 x 6 image (pretty small!) © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 3

· Raster images suffer from problems when we resize them. · If the previous image was displayed at the correct size (e. g. 6 x 6 pixels) it would appear as a tiny circle. · In the previous slide we magnified it hugely and hence it doesn’t look very good anymore. · Examples of raster file formats are GIF, JPEG, PNG, BMP. · Vector images look good at any size because instead of being simply squares on a grid, vector images store shapes in terms of their underlying maths. · For example a vector representation of a circle would store the equation of the circle. · When you create images using a drawing package you are usually using vector graphics. · The resultant files are smaller in size but can’t really represent photographic style images like raster formats can. · A common vector format is EPS (encapsulated postscript) · Macromedia’s Flash format is also vector based. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 4

· 3 D formats describe three-dimensional objects and environments. These descriptions can be used by appropriate software to produce images of these objects and environments. · For example, Computer Aided Design (CAD) packages like Auto. Cad, use the DXF format. · Another example is the VRML format which is used to add 3 D objects and worlds to web pages. If the browser has the capability of viewing VRML then the user will see an image on the page and be able to move around, rotate objects etc. . · This discussion will be primarily about raster formats as the bulk of the graphics on the web uses these techniques. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 5

Colours · Raster formats allow the specification of coloured images by making use of the RGB (Red Green Blue) colour model. · This model represents colours as numerical triples, where each element of the triple represents the proportion of each of the three primary colours which are present. · So each element of the triple may vary from 0 to 255. · So a colour might be (120, 46, 0) · which intuitively means “ a lot of red, some blue, no green”. · Note that this technique allows us to specify about 16 million different colours (256 x 256). · This is called 24 -bit colour (or true colour). Why ? © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 6

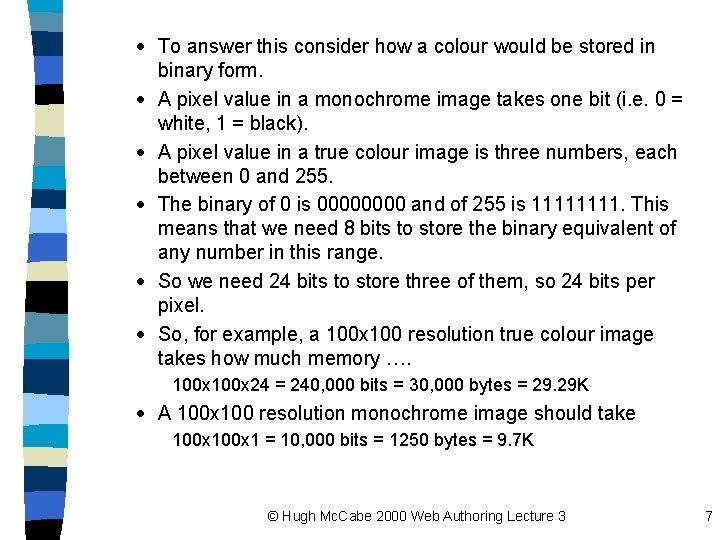

· To answer this consider how a colour would be stored in binary form. · A pixel value in a monochrome image takes one bit (i. e. 0 = white, 1 = black). · A pixel value in a true colour image is three numbers, each between 0 and 255. · The binary of 0 is 0000 and of 255 is 1111. This means that we need 8 bits to store the binary equivalent of any number in this range. · So we need 24 bits to store three of them, so 24 bits per pixel. · So, for example, a 100 x 100 resolution true colour image takes how much memory …. 100 x 24 = 240, 000 bits = 30, 000 bytes = 29. 29 K · A 100 x 100 resolution monochrome image should take 100 x 1 = 10, 000 bits = 1250 bytes = 9. 7 K © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 7

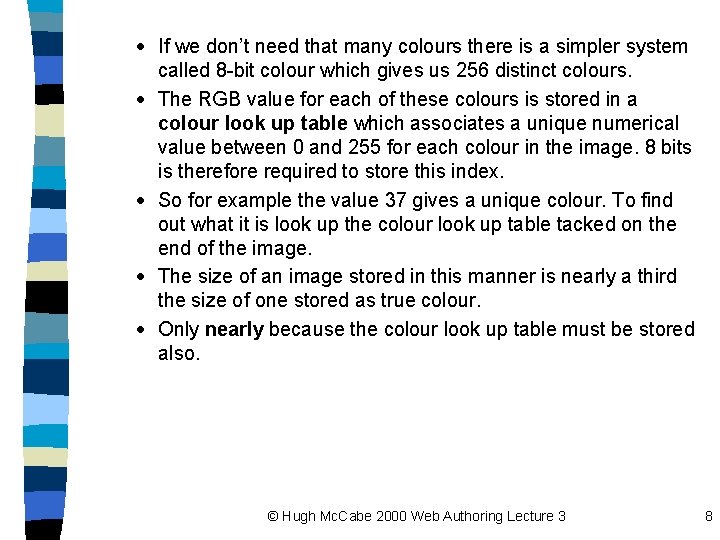

· If we don’t need that many colours there is a simpler system called 8 -bit colour which gives us 256 distinct colours. · The RGB value for each of these colours is stored in a colour look up table which associates a unique numerical value between 0 and 255 for each colour in the image. 8 bits is therefore required to store this index. · So for example the value 37 gives a unique colour. To find out what it is look up the colour look up table tacked on the end of the image. · The size of an image stored in this manner is nearly a third the size of one stored as true colour. · Only nearly because the colour look up table must be stored also. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 8

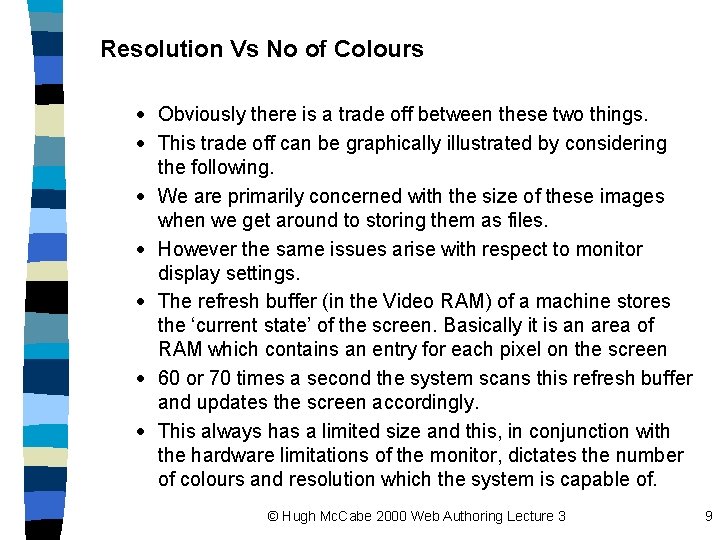

Resolution Vs No of Colours · Obviously there is a trade off between these two things. · This trade off can be graphically illustrated by considering the following. · We are primarily concerned with the size of these images when we get around to storing them as files. · However the same issues arise with respect to monitor display settings. · The refresh buffer (in the Video RAM) of a machine stores the ‘current state’ of the screen. Basically it is an area of RAM which contains an entry for each pixel on the screen · 60 or 70 times a second the system scans this refresh buffer and updates the screen accordingly. · This always has a limited size and this, in conjunction with the hardware limitations of the monitor, dictates the number of colours and resolution which the system is capable of. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 9

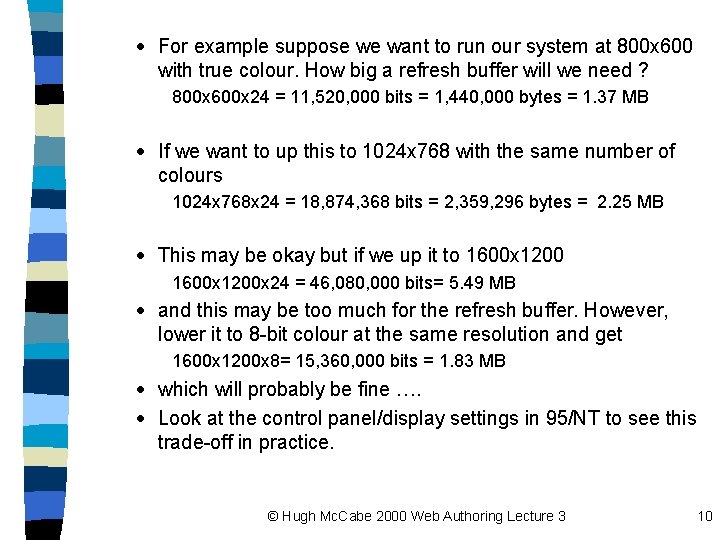

· For example suppose we want to run our system at 800 x 600 with true colour. How big a refresh buffer will we need ? 800 x 600 x 24 = 11, 520, 000 bits = 1, 440, 000 bytes = 1. 37 MB · If we want to up this to 1024 x 768 with the same number of colours 1024 x 768 x 24 = 18, 874, 368 bits = 2, 359, 296 bytes = 2. 25 MB · This may be okay but if we up it to 1600 x 1200 x 24 = 46, 080, 000 bits= 5. 49 MB · and this may be too much for the refresh buffer. However, lower it to 8 -bit colour at the same resolution and get 1600 x 1200 x 8= 15, 360, 000 bits = 1. 83 MB · which will probably be fine …. · Look at the control panel/display settings in 95/NT to see this trade-off in practice. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 10

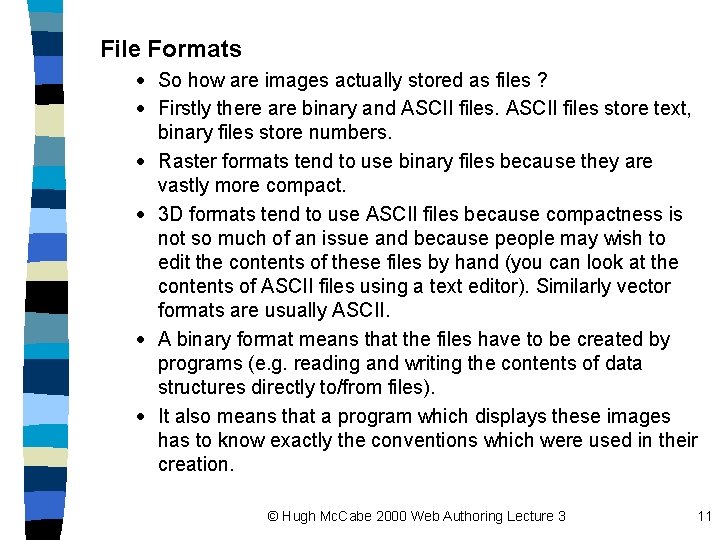

File Formats · So how are images actually stored as files ? · Firstly there are binary and ASCII files store text, binary files store numbers. · Raster formats tend to use binary files because they are vastly more compact. · 3 D formats tend to use ASCII files because compactness is not so much of an issue and because people may wish to edit the contents of these files by hand (you can look at the contents of ASCII files using a text editor). Similarly vector formats are usually ASCII. · A binary format means that the files have to be created by programs (e. g. reading and writing the contents of data structures directly to/from files). · It also means that a program which displays these images has to know exactly the conventions which were used in their creation. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 11

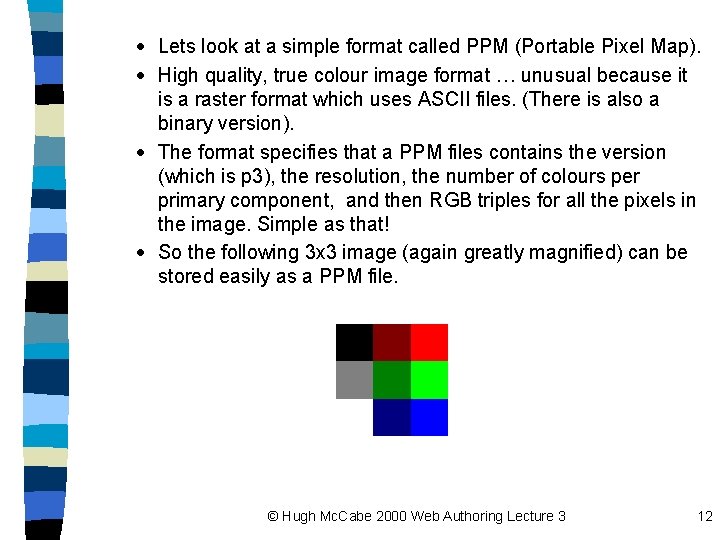

· Lets look at a simple format called PPM (Portable Pixel Map). · High quality, true colour image format … unusual because it is a raster format which uses ASCII files. (There is also a binary version). · The format specifies that a PPM files contains the version (which is p 3), the resolution, the number of colours per primary component, and then RGB triples for all the pixels in the image. Simple as that! · So the following 3 x 3 image (again greatly magnified) can be stored easily as a PPM file. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 12

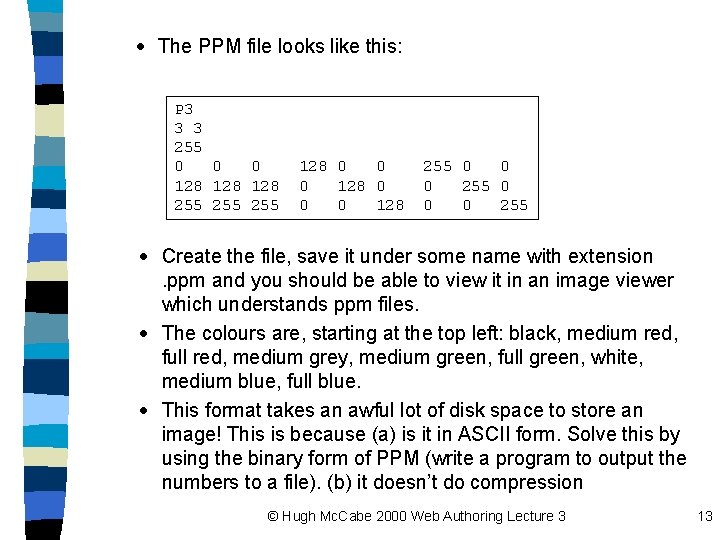

· The PPM file looks like this: P 3 3 3 255 0 0 0 128 128 255 255 128 0 0 0 128 255 0 0 0 255 · Create the file, save it under some name with extension. ppm and you should be able to view it in an image viewer which understands ppm files. · The colours are, starting at the top left: black, medium red, full red, medium grey, medium green, full green, white, medium blue, full blue. · This format takes an awful lot of disk space to store an image! This is because (a) is it in ASCII form. Solve this by using the binary form of PPM (write a program to output the numbers to a file). (b) it doesn’t do compression © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 13

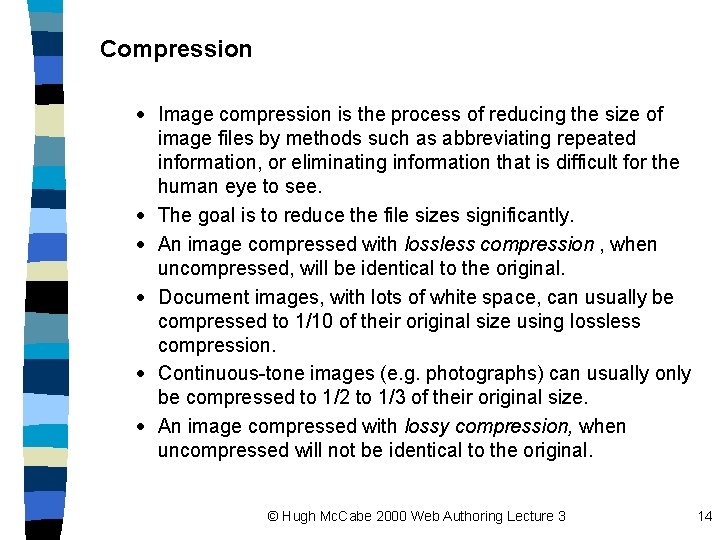

Compression · Image compression is the process of reducing the size of image files by methods such as abbreviating repeated information, or eliminating information that is difficult for the human eye to see. · The goal is to reduce the file sizes significantly. · An image compressed with lossless compression , when uncompressed, will be identical to the original. · Document images, with lots of white space, can usually be compressed to 1/10 of their original size using lossless compression. · Continuous-tone images (e. g. photographs) can usually only be compressed to 1/2 to 1/3 of their original size. · An image compressed with lossy compression, when uncompressed will not be identical to the original. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 14

· In other words, some data will be lost. However, a well designed lossy compression algorithm for images, will try to ensure that the lost data will not affect the image (i. e. the difference will not be noticeable to the human eye). · Many different techniques can be used to achieve compression of images. · For example, run-length encoding works as follows. · Take each horizontal row of the image in turn. · Suppose one row is all white pixels (e. g. RGB value 255 255). · If the row is 100 pixels wide then this will need 100 x 24 bits of storage (assume true colour). This is 300 bytes. · Run-length encoding divides a row of pixels into ‘runs’. · Each run is a sequence of pixels with the same RGB value. · So the example above has a run of white pixels 100 in length. · This is then stored not as 100 RGB values but as one RGB value and a number indicating the length of the run. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 15

· So it will be stored as 100 255 255. This will take up 4 bytes of memory, a considerable saving. · This is a lossless compression method. · Sophisticated lossy compression methods work by analysing sections of the image and ‘averaging out’ values within these subsections. For example suppose we divide the image up into 8 x 8 sections. · Suppose we find one of these sections contains RGB values which are the same. We then only need to store the RGB value once, along with the location of the section. · Suppose the section contains nearly the same values. Then a lossy compression method may simply average them out and store that. · In general they work by noting that subtle changes in colour are not that visible to the eye so they can be discarded without significant degradation in quality. · Significant changes in relative brightness however, are significant, so these have to be retained as much as possible. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 16

Image File Formats for the Web · A piece of software can only display an image in a particular format if it is programmed to do so. · Since a web browser is a piece of software this applies to web browsers also. · Generally web browsers understand three image file formats GIF JPEG PNG The GIF format · This format is limited to 256 colour images. · Not a lot but sufficient for logos, buttons, backgrounds and most web graphics © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 17

· This limitation on the number of colours has advantages however …. · 1. The 256 colour problem ! · Many users may be browsing on computers which are only capable of viewing 256 colours anyway. By using images which have more than 256 colours you are creating problems for them · Basically they will not see the image as you designed it as their browser will be forced to display the image with less colours than it really has and this leads to distortion and unpredictable results. · Solution is to use GIFS which automatically restrict you to 256 colours anyway …. right ? · Well, not quite, because the 256 colours used in your image may not necessarily be the same 256 which the browser at the other end is capable of displaying. So the colours will change … sometimes subtly …. sometimes drastically. · This is the colour mapping problem. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 18

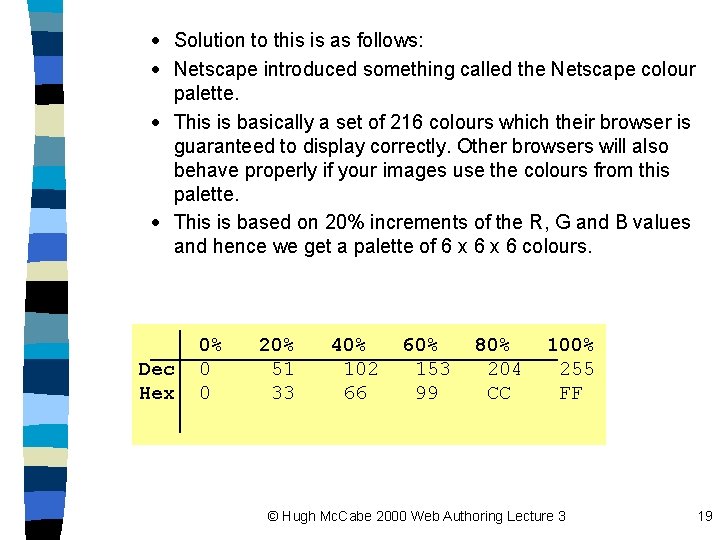

· Solution to this is as follows: · Netscape introduced something called the Netscape colour palette. · This is basically a set of 216 colours which their browser is guaranteed to display correctly. Other browsers will also behave properly if your images use the colours from this palette. · This is based on 20% increments of the R, G and B values and hence we get a palette of 6 x 6 colours. Dec Hex 0% 0 0 20% 51 33 40% 102 66 60% 153 99 80% 204 CC 100% 255 FF © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 19

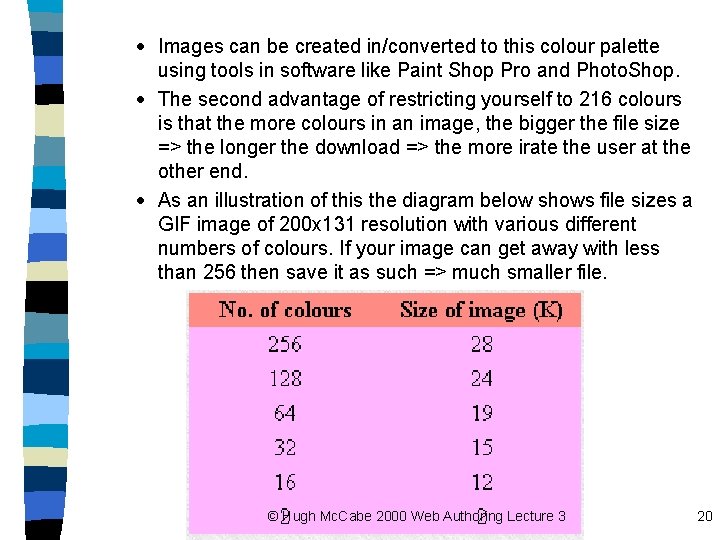

· Images can be created in/converted to this colour palette using tools in software like Paint Shop Pro and Photo. Shop. · The second advantage of restricting yourself to 216 colours is that the more colours in an image, the bigger the file size => the longer the download => the more irate the user at the other end. · As an illustration of this the diagram below shows file sizes a GIF image of 200 x 131 resolution with various different numbers of colours. If your image can get away with less than 256 then save it as such => much smaller file. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 20

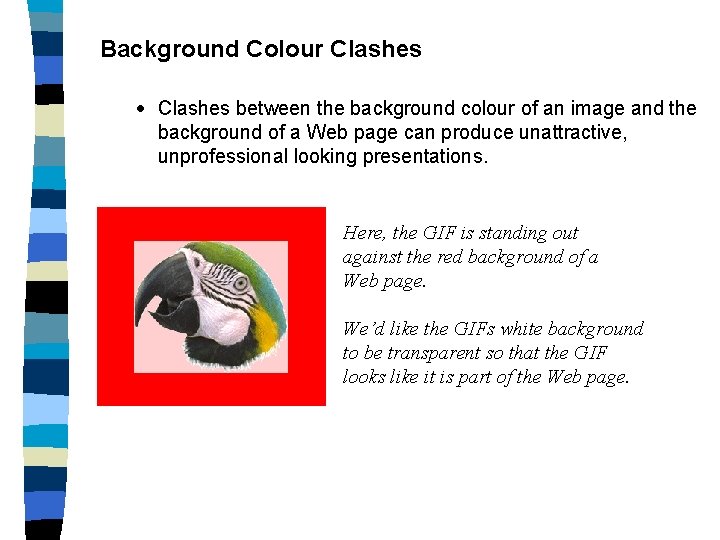

Background Colour Clashes · Clashes between the background colour of an image and the background of a Web page can produce unattractive, unprofessional looking presentations. Here, the GIF is standing out against the red background of a Web page. We’d like the GIFs white background to be transparent so that the GIF looks like it is part of the Web page.

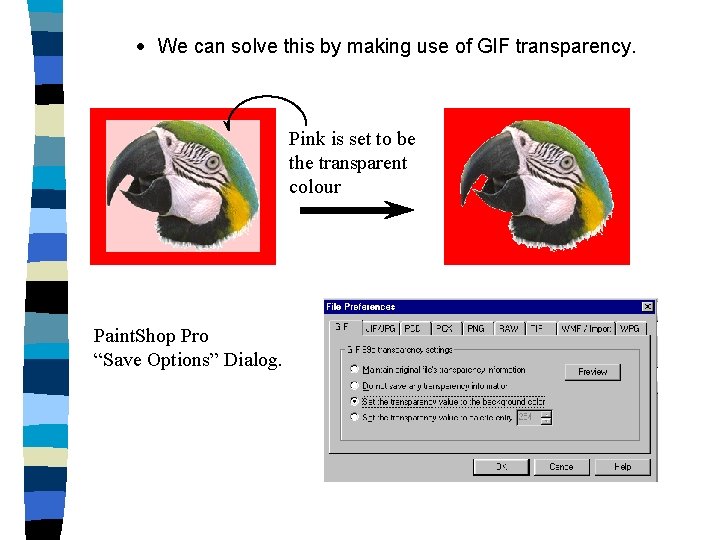

· We can solve this by making use of GIF transparency. Pink is set to be the transparent colour Paint. Shop Pro “Save Options” Dialog.

Global Colour Replacement · Transparent colour selections may occur throughout an image. · Watch out for anti-aliasing halos! No Transparency Halos and Transparency Artefacts

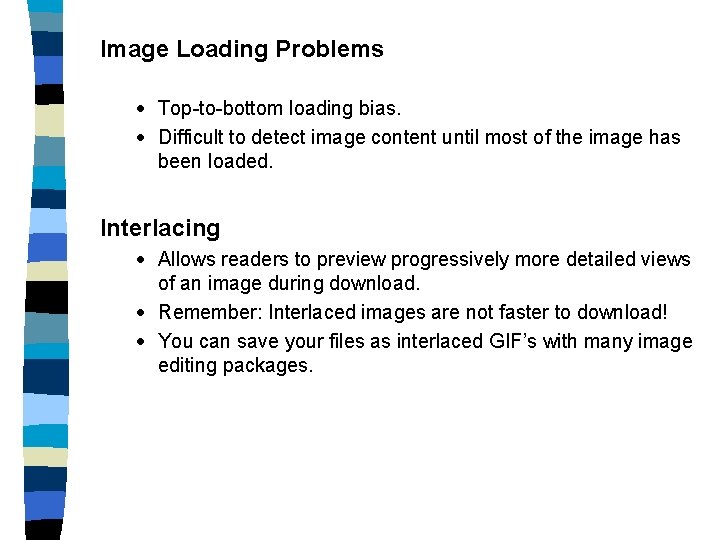

Image Loading Problems · Top-to-bottom loading bias. · Difficult to detect image content until most of the image has been loaded. Interlacing · Allows readers to preview progressively more detailed views of an image during download. · Remember: Interlaced images are not faster to download! · You can save your files as interlaced GIF’s with many image editing packages.

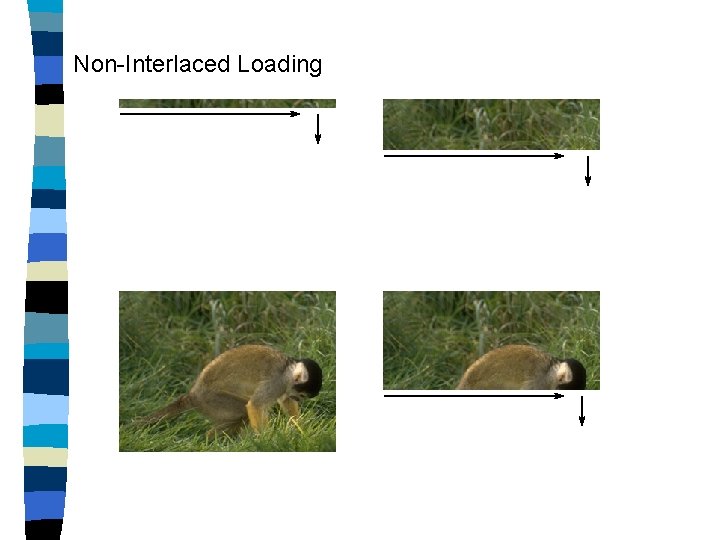

Non-Interlaced Loading

Interlaced Loading

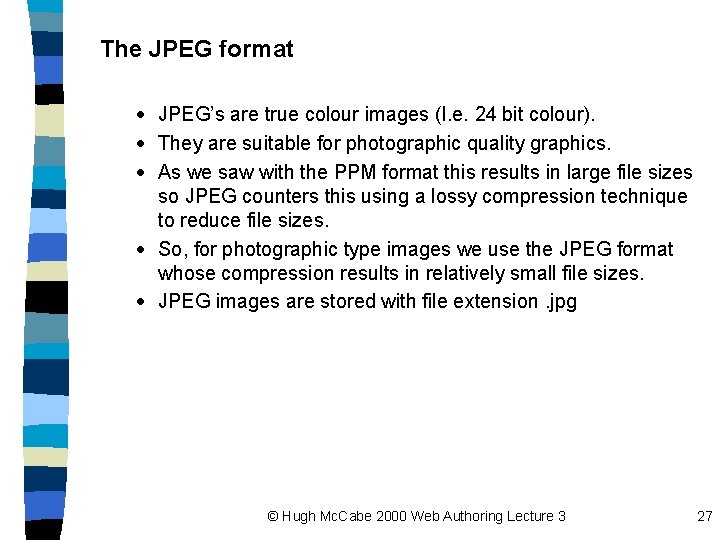

The JPEG format · JPEG’s are true colour images (I. e. 24 bit colour). · They are suitable for photographic quality graphics. · As we saw with the PPM format this results in large file sizes so JPEG counters this using a lossy compression technique to reduce file sizes. · So, for photographic type images we use the JPEG format whose compression results in relatively small file sizes. · JPEG images are stored with file extension. jpg © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 27

Image Processing · Image processing is the science of manipulating digital images to alter their appearance in some way. · There is a myriad of image processing operations which can be applied to images …. for example : - Changing the image size - Changing the colours (either operating individually or on the image as a whole) - Reducing or increasing the colour depth - Enhancing the contrast - Brightening/darkening the image - Blurring, distorting, morphing the image - Stretching the image - many more …. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 28

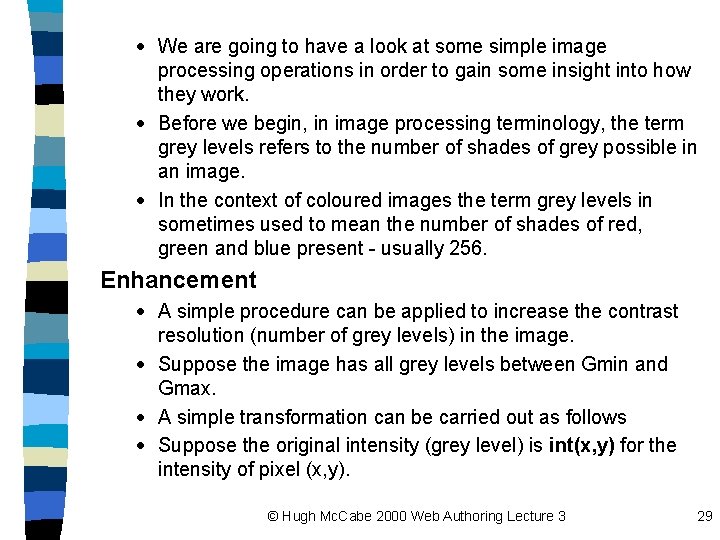

· We are going to have a look at some simple image processing operations in order to gain some insight into how they work. · Before we begin, in image processing terminology, the term grey levels refers to the number of shades of grey possible in an image. · In the context of coloured images the term grey levels in sometimes used to mean the number of shades of red, green and blue present - usually 256. Enhancement · A simple procedure can be applied to increase the contrast resolution (number of grey levels) in the image. · Suppose the image has all grey levels between Gmin and Gmax. · A simple transformation can be carried out as follows · Suppose the original intensity (grey level) is int(x, y) for the intensity of pixel (x, y). © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 29

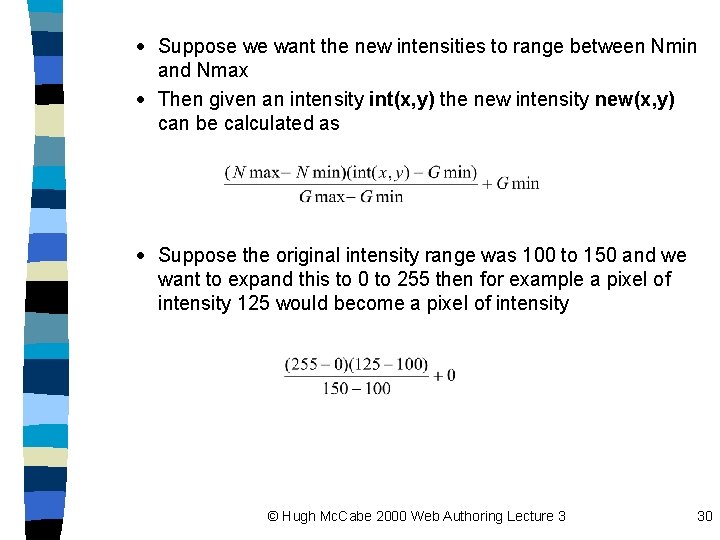

· Suppose we want the new intensities to range between Nmin and Nmax · Then given an intensity int(x, y) the new intensity new(x, y) can be calculated as · Suppose the original intensity range was 100 to 150 and we want to expand this to 0 to 255 then for example a pixel of intensity 125 would become a pixel of intensity © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 30

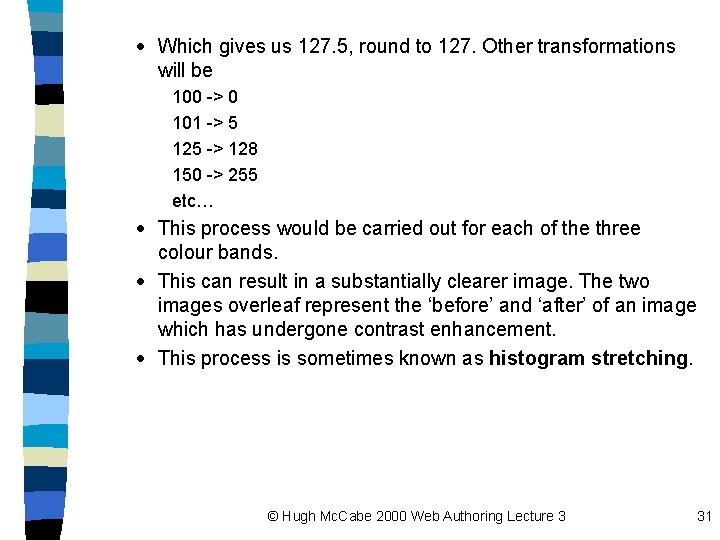

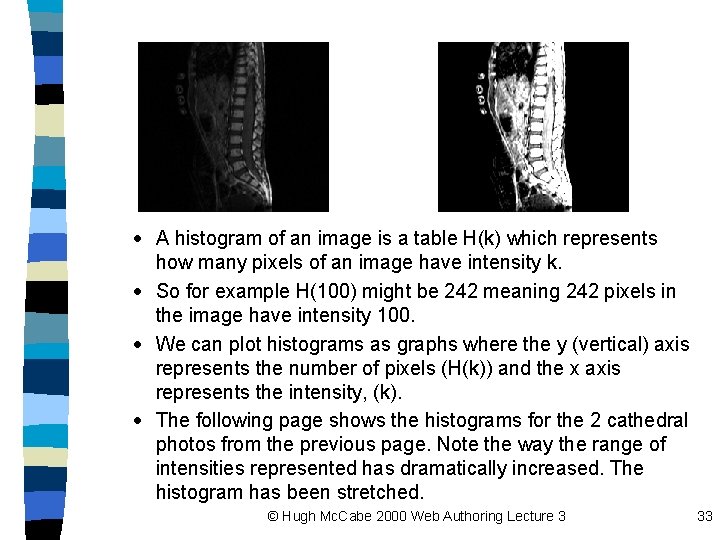

· Which gives us 127. 5, round to 127. Other transformations will be 100 -> 0 101 -> 5 125 -> 128 150 -> 255 etc… · This process would be carried out for each of the three colour bands. · This can result in a substantially clearer image. The two images overleaf represent the ‘before’ and ‘after’ of an image which has undergone contrast enhancement. · This process is sometimes known as histogram stretching. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 31

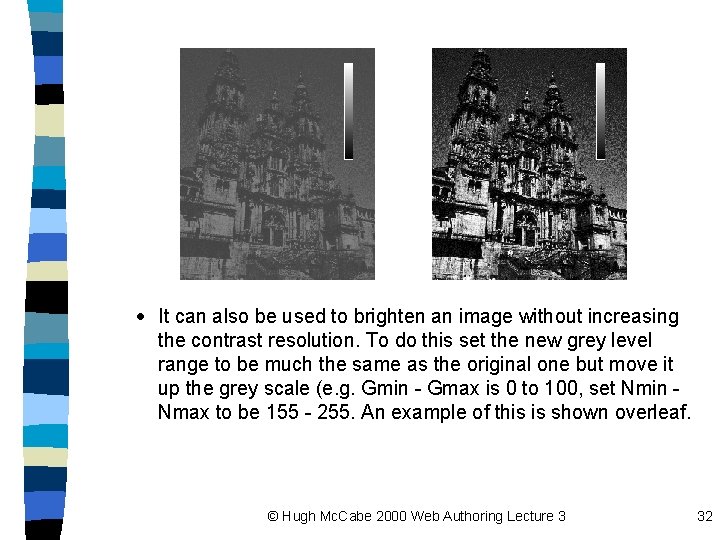

· It can also be used to brighten an image without increasing the contrast resolution. To do this set the new grey level range to be much the same as the original one but move it up the grey scale (e. g. Gmin - Gmax is 0 to 100, set Nmin Nmax to be 155 - 255. An example of this is shown overleaf. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 32

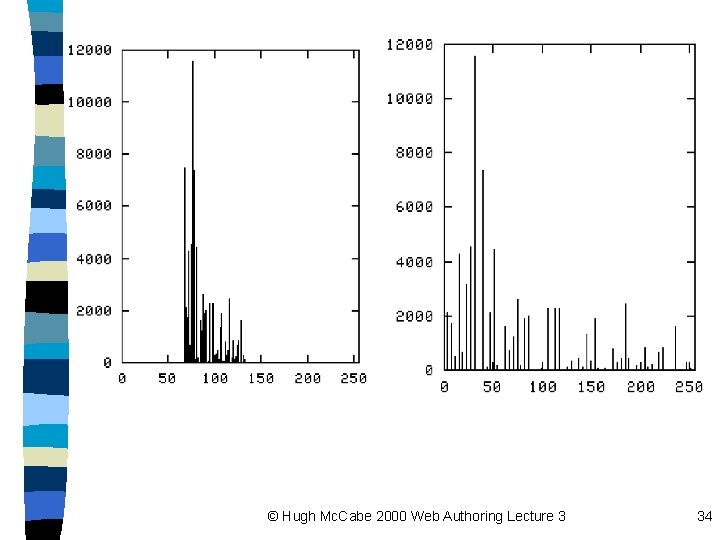

· A histogram of an image is a table H(k) which represents how many pixels of an image have intensity k. · So for example H(100) might be 242 meaning 242 pixels in the image have intensity 100. · We can plot histograms as graphs where the y (vertical) axis represents the number of pixels (H(k)) and the x axis represents the intensity, (k). · The following page shows the histograms for the 2 cathedral photos from the previous page. Note the way the range of intensities represented has dramatically increased. The histogram has been stretched. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 33

© Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 34

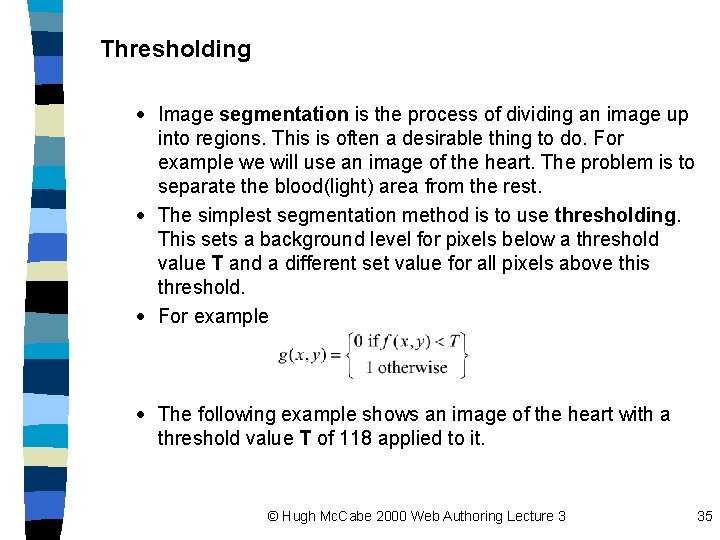

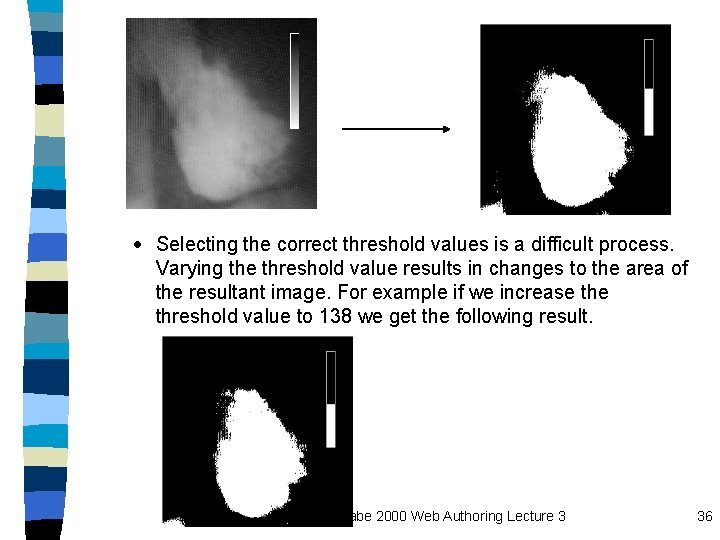

Thresholding · Image segmentation is the process of dividing an image up into regions. This is often a desirable thing to do. For example we will use an image of the heart. The problem is to separate the blood(light) area from the rest. · The simplest segmentation method is to use thresholding. This sets a background level for pixels below a threshold value T and a different set value for all pixels above this threshold. · For example · The following example shows an image of the heart with a threshold value T of 118 applied to it. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 35

· Selecting the correct threshold values is a difficult process. Varying the threshold value results in changes to the area of the resultant image. For example if we increase threshold value to 138 we get the following result. © Hugh Mc. Cabe 2000 Web Authoring Lecture 3 36

- Slides: 36