Visual Knowledge Studying Imagery We have many different

- Slides: 19

Visual Knowledge

Studying Imagery We have many different types of knowledge: concepts, smells, tastes, sounds, tactile sensations, and, of course, visual images. Given the general importance we place on our visual sense, we will focus on “visual imagery. When asked to create an image in your mind, what are you looking at with your “mind’s eye? Is it similar to a photograph? I can’t simply ask you to “describe” your mental images, because the manner in which you describe images may not be the same way I describe images.

Studying Imagery (con’t) Researchers use “chronometric” studies (i. e. , RT). If asked to “describe” a cat, you would likely mention specific features of cats (e. g. , whiskers, claws, fangs, etc). Thus, a “description” will contain distinctive features strongly associated with the object. If asked to “draw” a cat, you would certainly put a head on it, but you probably didn’t mention that in your description. Thus, a “depiction” contains size and position information. What information is provided depends on the mode of presentation.

Studying Imagery (con’t) Which is the case with “mental images”? It depends on whether we’re asked to “visualize a cat” or simply “think of a cat. ” Volunteers respond more quickly to “Does a the cat have a head? ” than to “Does the cat have claws? ” when asked to “visualize” a cat, but just the opposite when asked to “think” of a cat. We can think of cats or visualize cats and the pattern of information availability changes. This implies our mental images are “picture-like. ”

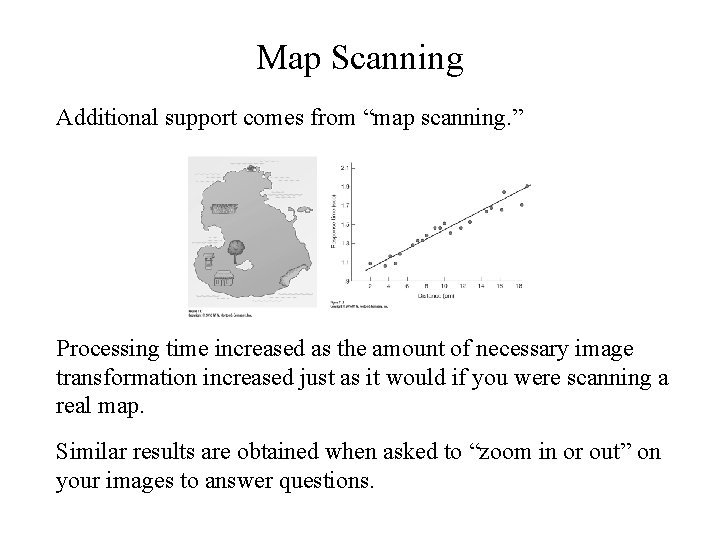

Map Scanning Additional support comes from “map scanning. ” Processing time increased as the amount of necessary image transformation increased just as it would if you were scanning a real map. Similar results are obtained when asked to “zoom in or out” on your images to answer questions.

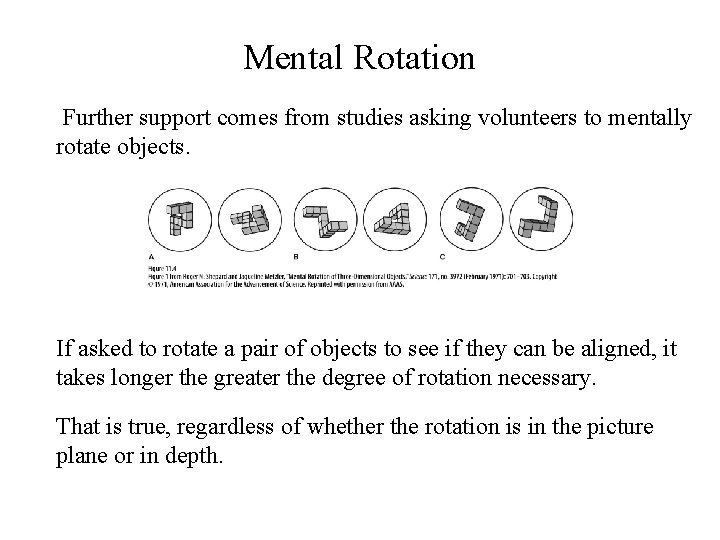

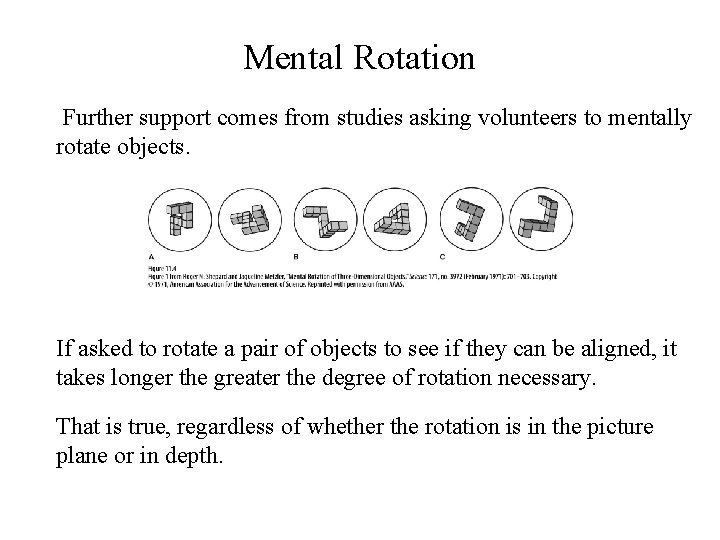

Mental Rotation Further support comes from studies asking volunteers to mentally rotate objects. If asked to rotate a pair of objects to see if they can be aligned, it takes longer the greater the degree of rotation necessary. That is true, regardless of whether the rotation is in the picture plane or in depth.

Imagery and Perception If images are similar to actual pictures, are images subject to the same mental processes of perception as viewing real pictures? In short, “yes. ” • • Interference Priming Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) Brain damage Those results support the idea that images are subject to the same kinds of mental processes as perception, even at the neurological level!

Spatial Images and Visual Images Studies have examined individuals who were blind since birth on the same tasks we’ve been discussing and have found the same kinds of results: the greater the imaged transformation, the longer it takes. Since the blind can’t see, however, they use “spatial imagery” to accomplish the tasks. It seems reasonable, then, that a sighted person could use either type of imagery (although about 10% of the population report having no visual imagery ability at all). How is a spatial imagery different than visual imagery?

Spatial Images and Visual Images (con’t) One difference is brain localization. Brain scanning studies confirm different areas of the brain are used for visual (occipital lobe) than for spatial tasks (parietal lobe). Additionally, damage to visual areas does not interfere with spatial imagery and damage to spatial areas does not interfere with visual imagery. Nature of the task: a visual task (e. g. , imagine what something looks like) would likely call for visual imagery, while a spatial task (e. g. , navigating to a particular location, like the Equestrian Center) would likely call for spatial imagery. Some tasks can be approached with either type of imagery (e. g. , map scanning), and so you may choose the type of imagery at which you are better.

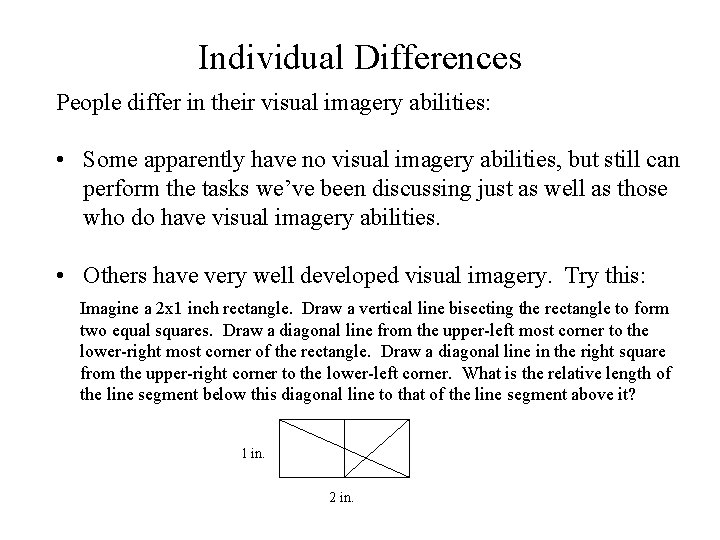

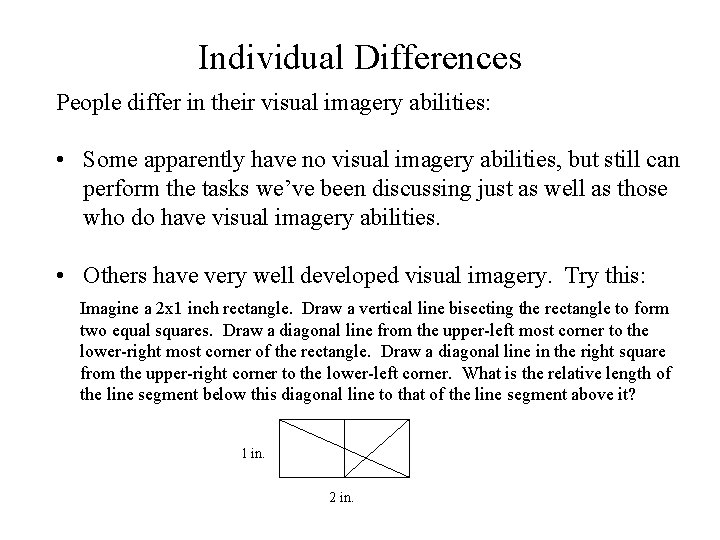

Individual Differences People differ in their visual imagery abilities: • Some apparently have no visual imagery abilities, but still can perform the tasks we’ve been discussing just as well as those who do have visual imagery abilities. • Others have very well developed visual imagery. Try this: Imagine a 2 x 1 inch rectangle. Draw a vertical line bisecting the rectangle to form two equal squares. Draw a diagonal line from the upper-left most corner to the lower-right most corner of the rectangle. Draw a diagonal line in the right square from the upper-right corner to the lower-left corner. What is the relative length of the line segment below this diagonal line to that of the line segment above it? 1 in. 2 in. .

Individual Differences (con’t) At the extreme end are those individuals with “eidetic imagery” (i. e. , photographic memory). Let’s see how much you can remember… That level of visual imagery ability, however, is quite rare and we do not know much about that form of imagery.

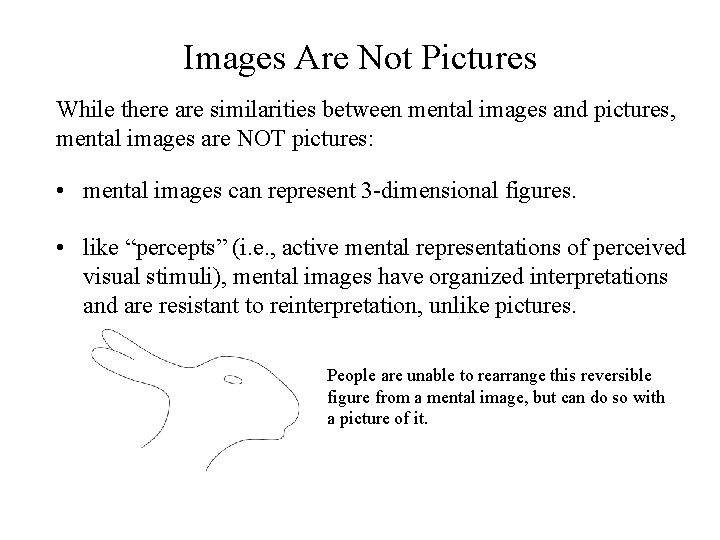

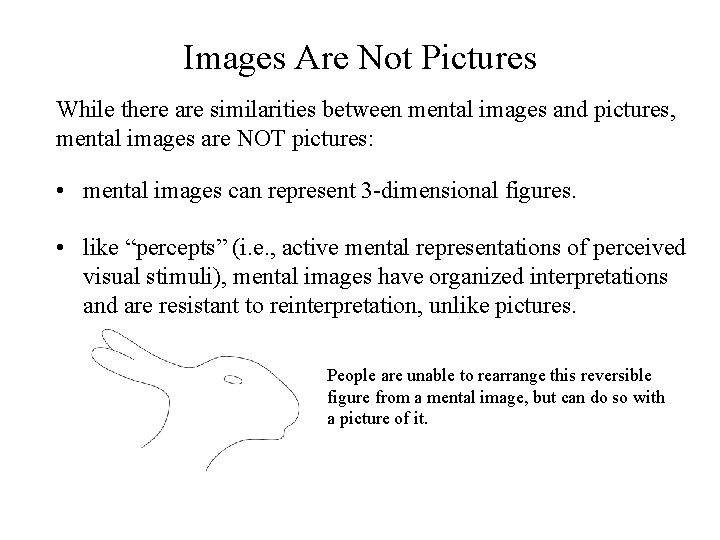

Images Are Not Pictures While there are similarities between mental images and pictures, mental images are NOT pictures: • mental images can represent 3 -dimensional figures. • like “percepts” (i. e. , active mental representations of perceived visual stimuli), mental images have organized interpretations and are resistant to reinterpretation, unlike pictures. People are unable to rearrange this reversible figure from a mental image, but can do so with a picture of it.

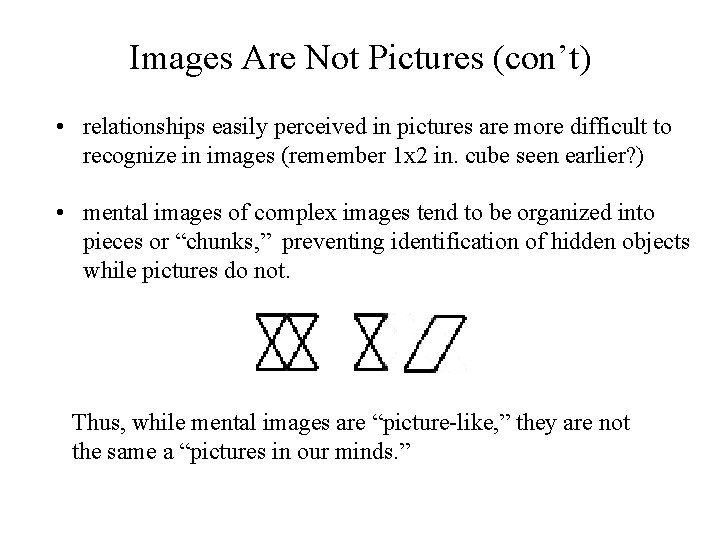

Images Are Not Pictures (con’t) • relationships easily perceived in pictures are more difficult to recognize in images (remember 1 x 2 in. cube seen earlier? ) • mental images of complex images tend to be organized into pieces or “chunks, ” preventing identification of hidden objects while pictures do not. Thus, while mental images are “picture-like, ” they are not the same a “pictures in our minds. ”

Long-Term Visual Memory Is visual information in LTM represented in the same way as “active” images in working memory? Research indicates you first activate the appropriate “image frame” (i. e. , the form’s general, global shape), and then add other pieces to fill out the image (think of a police sketch kit). You can add as many or as few pieces as needed to achieve the desired degree of detail in the image. The “instructions” of how to assemble the image are contained in a set of “verbal” instructions represented by “propositions” (think of describing a suspect to a sketch artist).

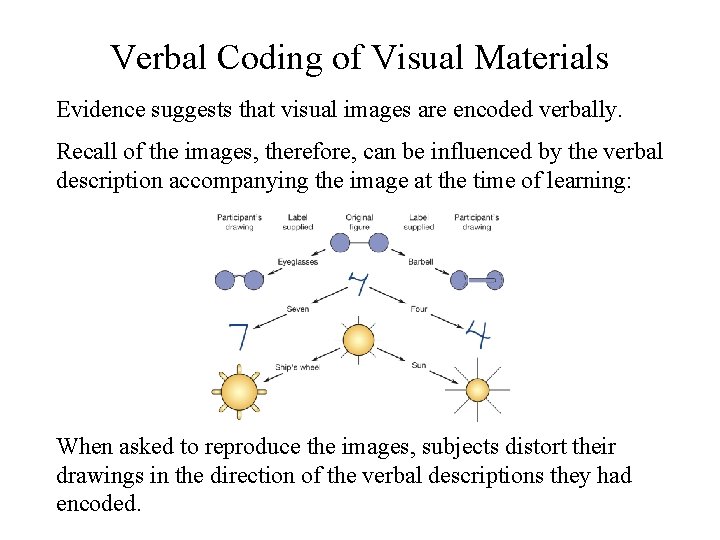

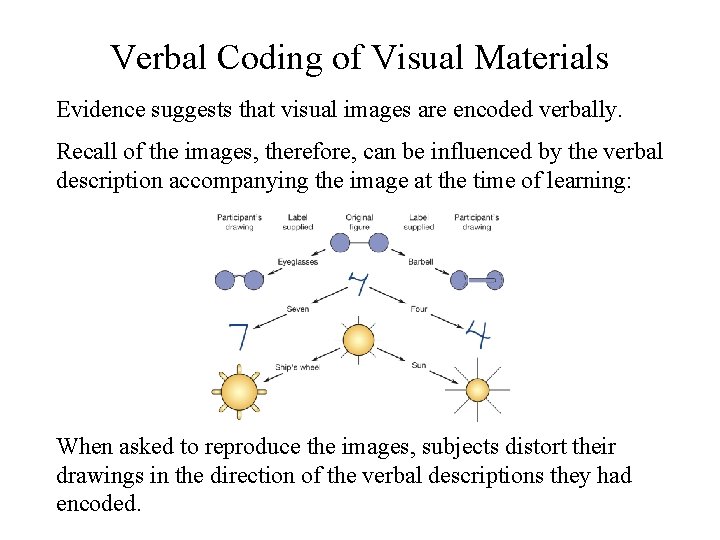

Verbal Coding of Visual Materials Evidence suggests that visual images are encoded verbally. Recall of the images, therefore, can be influenced by the verbal description accompanying the image at the time of learning: When asked to reproduce the images, subjects distort their drawings in the direction of the verbal descriptions they had encoded.

Imagery Helps Memory Even though our images may be represented as propositions, images are very helpful in memory. Materials accompanied by images are easier to recall: • high-imagery words (e. g. , church) are more likely recalled than low-imagery words (e. g. , virtue) • imagery mnemonics are superior (generally) to other methods of remembering (e. g. , rote rehearsal, sentence construction), but only if images of objects are interacting in some way (i. e. , it helps provide “organization” of the material)

Dual Coding How does imagery improve memory? • First, it can provide organization of information: organized information is easier to recall. • Secondly, high-imagery words have “dual coding. ” That is, they are coded verbally and visually. The dual coding provides two chances to locate the desired information at recall: you may remember the verbal label or the image.

Memory For Pictures Visual information is subject to the same influences we previously discussed regarding verbal material: primacy and recency effects, spread of activation, encoding specificity, and etc. For example, schemata influences can be observed in same/different comparisons. Subjects were shown a series of pictures (e. g. , a kitchen) containing some “unexpected” items (e. g. , a fireplace). When viewed again at a later time and asked if the picture was the same or had been altered, subjects made errors consistent with their schemata for the objects “Boundary Extension” – people misrecall a picture showing more than the actual boundaries of the photograph.

The Diversity Of Knowledge Despite the differences between images and verbal information, it seems that images are stored in LTM in the same was as verbal information and are subject to the same principles (e. g. , rehearsal improves recall). We have yet to research other categories of information (e. g. , smells, tastes, etc) very extensively. The question remains, then, of whether those other categories of information are also subject to the same LTM principles.