VIRTUE ETHICS Virtue ethics is a broad term

VIRTUE ETHICS

• Virtue ethics is a broad term for theories that emphasize the role of character and virtue rather than duty or good consequences. • A virtue ethicist is likely to give you this kind of moral advice: “Act as a virtuous person would act in your situation. ” • What does that mean? • Most virtue ethics theories derive from Aristotle (384 -322 BCE) who argued that a virtuous person is one who has ideal character traits. These traits derive from natural internal tendencies, but need to be nurtured; once established, they will become stable. • For example, a virtuous person is someone who is kind across many situations over a lifetime because that is her character and not because she wants to maximize utility or gain favors or simply do her duty.

• Virtue Ethics emphasizes Virtues (Strengths) and Vices (Weaknesses) of Character • Unlike deontological and consequentialist theories, virtue ethics does not aim primarily to identify universal principles that can be applied in any moral situation. • Not “What Should I Do? ” (both Deontology and Teleology) but “What Kind of Person Should I Be? ”

The Goal of Human Existence Eudaimonia Flourishing, Happiness activity, exhibiting virtue in accordance with reason. Eudaimonia derives from Aristotle's understanding of human nature: that reason is unique to human beings the ideal function of a human being is the most perfect exercise of reason.

The Goal of Human Existence & Eudaimonia Goal is flourishing through virtuous activity. Human happiness is the activity of the soul (reasoning well) in accordance with perfect virtue (excellence). Aristotle defines Eudaimonia (living well) as the good. It is our ‘final end’, and we never seek it for any other purpose. But this doesn’t tell us what Eudaimonia is.

FUNCTION AND VIRTUE ‘The ‘characteristic activity’ provides an insight into what type of thing Eudaimonia is. If the function of a knife is to cut, a good knife cuts well; a good eye sees well; a good plant flourishes (it grows well, produces flowers well, etc. , according to its species). In order to fulfil its function, a thing will need certain qualities. An that aid the fulfilment of a thing’s function. A quality is an ‘excellence’, or more specifically, a ‘virtue’. So sharpness is a virtue in a knife designed to cut. Good focus is a virtue in an eye.

Aristotle applies this entire account to human beings. Virtues for human beings will be those traits that enable them to fulfil their function. So, what is the ‘characteristic activity’ or function of human beings? A human life is distinctively the life of a being that can be guided by reason. We are, distinctively, rational animals.

Now, a knife, eye, tool, etc. ) is one that performs its function well, and that it will need certain qualities–virtues–to enable it to do this. Our function will be living in accordance with reason, and the virtues of a human being will be what enables this. Only the virtuous person can achieve Eudaimonia. To fulfil our function and live well, we must be guided by the ‘right’ reasons. So Eudaimonia consists in the activity of the soul which exhibits the virtues by being in accordance with reason. Finally, we must add that this must apply to a person’s life as a whole. A day or even year of living well doesn’t amount to a good life

There are three thing that are good for us ◦ 1 goods of the mind (e. g. intelligence, wisdom, etc. ) ◦ 2. goods of the body (e. g. strength, health, etc. ) ◦ 3. ‘external’ goods (e. g. wealth, food, etc. ). Eudaimonia centrally concerns goods ‘of the soul’. To simply possess virtue is not enough; Eudaimonia requires that one acts on it as well. The employment of good qualities and the achievement of good purposes are better than simply having the disposition to do so. A virtuous person loves living virtuously. Eudaimonia is therefore both good and pleasant. In order to live virtuously, e. g. to be generous, we will also need a certain amount of external goods. And so, enough good fortune is needed for a fully good life.

Because our function is the activity of the soul in accordance with reason, a virtue is a trait of a person’s ‘soul’. We can divide the soul into an a-rational part, and a rational part. The a-rational part can be further divided in two: ◦ the part that is related to ‘growth and nutrition’ ◦ the part related to desire and emotion. The desiring part we share with other animals, Virtues are traits that enable us to live in accordance with reason. They are, therefore, of two kinds: ◦ virtues of the intellect (traits of the reasoning part) ◦ virtues of character (traits of the part characterized by desire and emotion)

The Virtues Intellectual Virtues ◦ Wisdom, Understanding, ◦ Taught through instruction Moral Virtues ◦ Prudence, Justice, Fortitude, Temperance ◦ The result of habit ◦ Not natural or inborn but acquired through practice ◦ Habit or disposition of the soul (our fundamental character) which involves both feeling and action

Virtues Prudence Compassion Generosity Benevolence Wisdom Justice Courage Temperance

The Doctrine of the Mean Proper position between ◦ Vice of excess ◦ Vice of deficiency two extremes Not an arithmetic median ◦ Relative to us and not the thing ◦ Not the same for all of us, or ◦ “In this way, then, every knowledgeable person avoids excess and deficiency, but looks for the mean and chooses it” (II. 6)

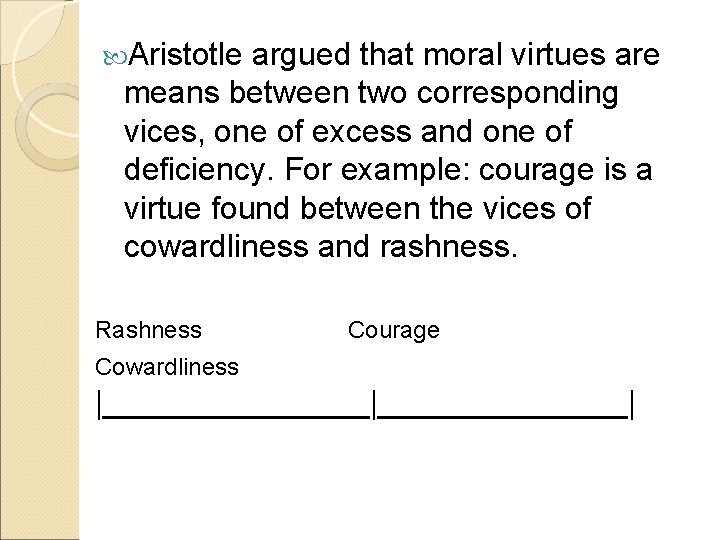

Aristotle argued that moral virtues are means between two corresponding vices, one of excess and one of deficiency. For example: courage is a virtue found between the vices of cowardliness and rashness. Rashness Courage Cowardliness |________|_______|

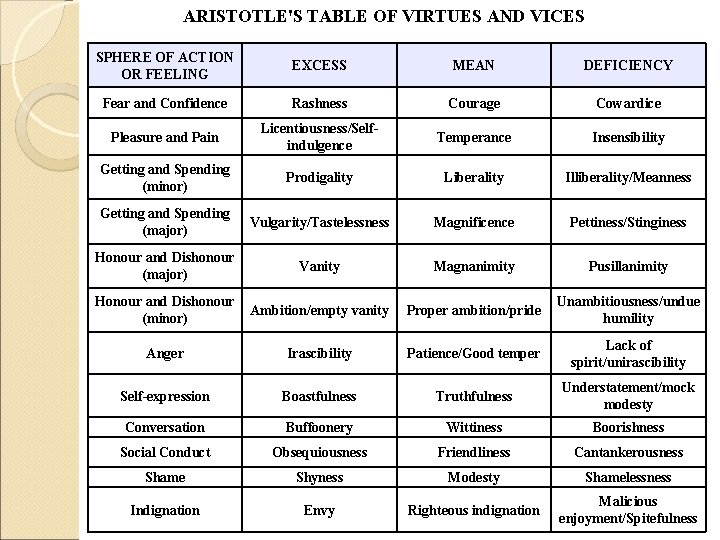

ARISTOTLE'S TABLE OF VIRTUES AND VICES SPHERE OF ACTION OR FEELING EXCESS MEAN DEFICIENCY Fear and Confidence Rashness Courage Cowardice Pleasure and Pain Licentiousness/Selfindulgence Temperance Insensibility Getting and Spending (minor) Prodigality Liberality Illiberality/Meanness Getting and Spending (major) Vulgarity/Tastelessness Magnificence Pettiness/Stinginess Honour and Dishonour (major) Vanity Magnanimity Pusillanimity Honour and Dishonour (minor) Ambition/empty vanity Proper ambition/pride Unambitiousness/undue humility Anger Irascibility Patience/Good temper Lack of spirit/unirascibility Self-expression Boastfulness Truthfulness Understatement/mock modesty Conversation Buffoonery Wittiness Boorishness Social Conduct Obsequiousness Friendliness Cantankerousness Shame Shyness Modesty Shamelessness Indignation Envy Righteous indignation Malicious enjoyment/Spitefulness

Other Virtue Ethicists Elizabeth Anscombe In 1958 she published “Modern Moral Philosophy” arguing. She criticized modern moral philosophy's pre-occupation with a law conception of ethics. A law conception of ethics deals exclusively with obligation and duty. Mill's utilitarianism and Kant's deontology rely on rules of morality that were claimed to be applicable to any moral situation. This approach to ethics relies on universal principles and results in a rigid moral code. Further, these rigid rules are based on a notion of obligation that is meaningless in modern, secular society because they make no sense without assuming the existence of a lawgiver—God.

Other Virtue Ethicists Philippa Foot Tries to modernise Aristotle. Ethics should not be about dry theorising, but about making the world a better place (she was one of the founders of Oxfam) Virtue contributes to the good life.

Other Virtue Ethicists Alasdair Mac. Intyre A large number of historical accounts of virtue that differ in their lists of the virtues and have incompatible theories of the virtues. He concludes that these differences are attributable to different practices that generate different conceptions of the virtues. Each account of virtue requires a prior account of social and moral features in order to be understood. Thus, in order to understand Homeric virtue you need to look its social role in Greek society. Virtues, then, are exercised within practices that are coherent, social forms of activity and seek to realize goods internal to the activity. The virtues enable us to achieve these goods. There is an end that transcends all particular practices and it constitutes the good of a whole human life.

Other Virtue Ethicists Rosalind Hursthouse A neo-Aristotelian – Aristotle was wrong on women and slaves, and there is no need to be limited to his list of virtues. We acquire virtues individually, and so flourish, but we do so together and not at each other’s expense.

Other Virtue Ethicists Carol In Gilligan a Different Voice (1982) Developmental theories have been built on observations and assumptions about men’s lives and thereby distort views of female personality. The kinds of virtues one honors depend on the power brokers of one’s society. The Ethics of Care

- Slides: 20