Using Newtons Laws Friction Circular Motion Drag Forces

- Slides: 65

Using Newton’s Laws: Friction, Circular Motion, Drag Forces Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

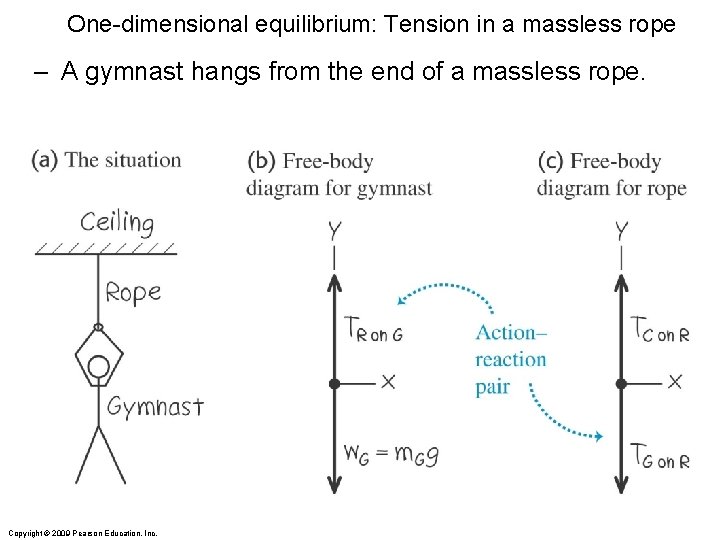

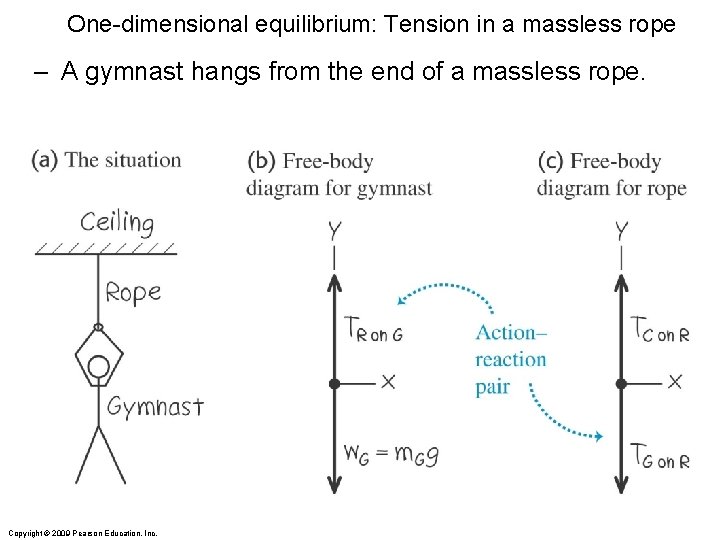

One-dimensional equilibrium: Tension in a massless rope – A gymnast hangs from the end of a massless rope. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

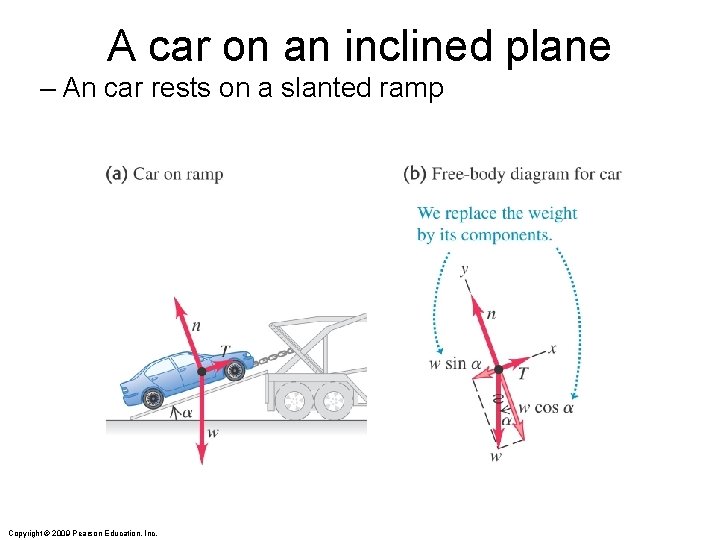

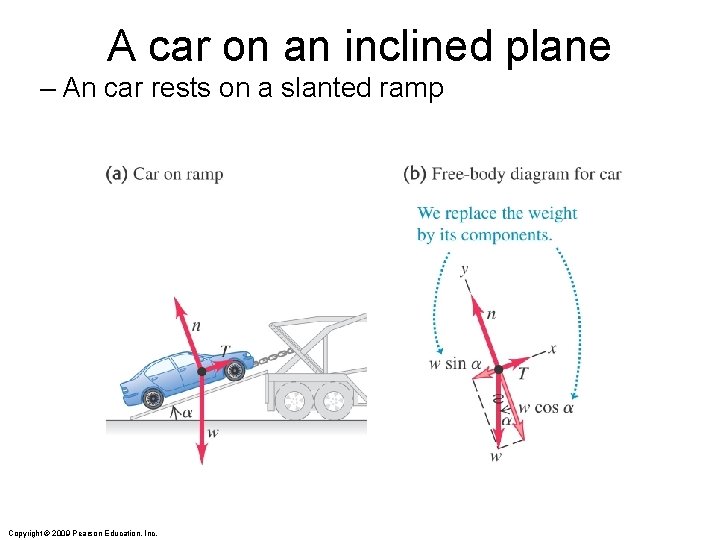

A car on an inclined plane – An car rests on a slanted ramp Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

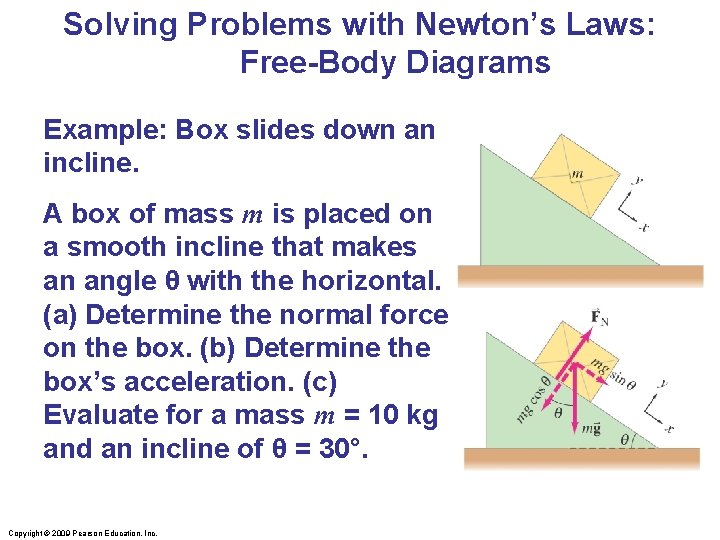

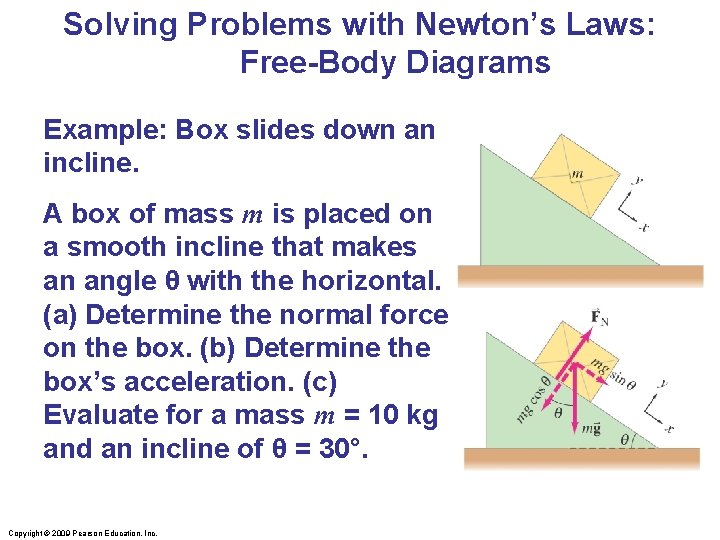

Solving Problems with Newton’s Laws: Free-Body Diagrams Example: Box slides down an incline. A box of mass m is placed on a smooth incline that makes an angle θ with the horizontal. (a) Determine the normal force on the box. (b) Determine the box’s acceleration. (c) Evaluate for a mass m = 10 kg and an incline of θ = 30°. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

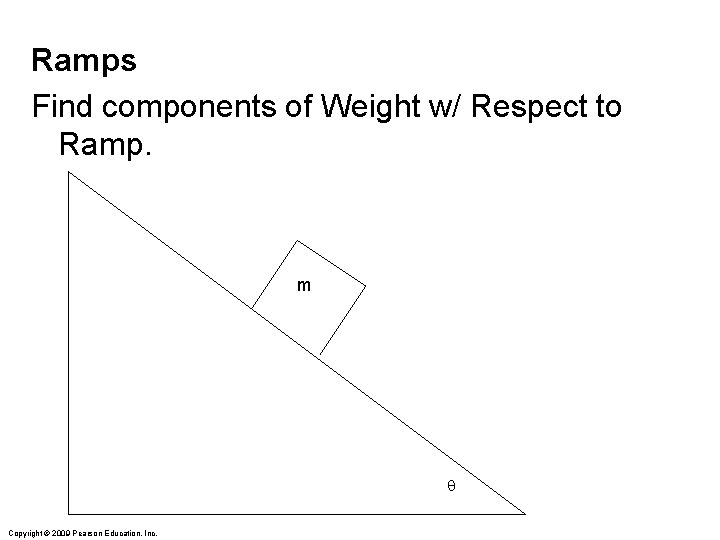

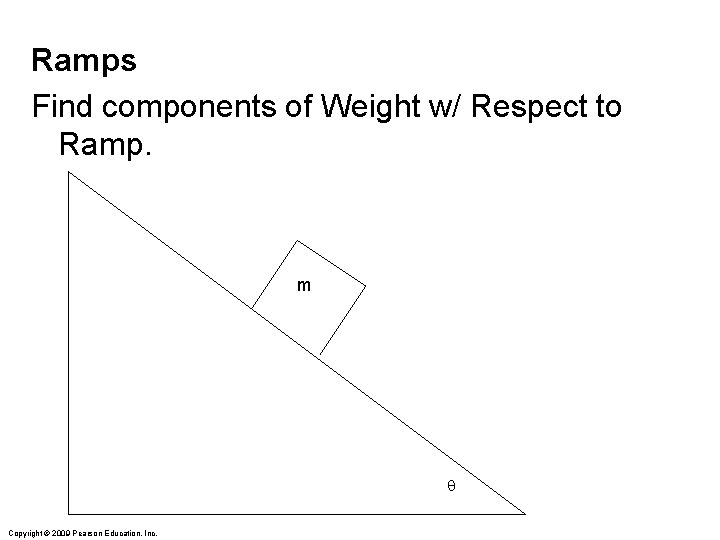

Ramps Find components of Weight w/ Respect to Ramp. m q Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Example: Find the force parallel on 25 kg object at the top of a 150 incline. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Ramps Find components of Weight w/ Respect to Ramp. m q Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Example: Find the force normal on 25 kg object at the top of a 150 incline. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

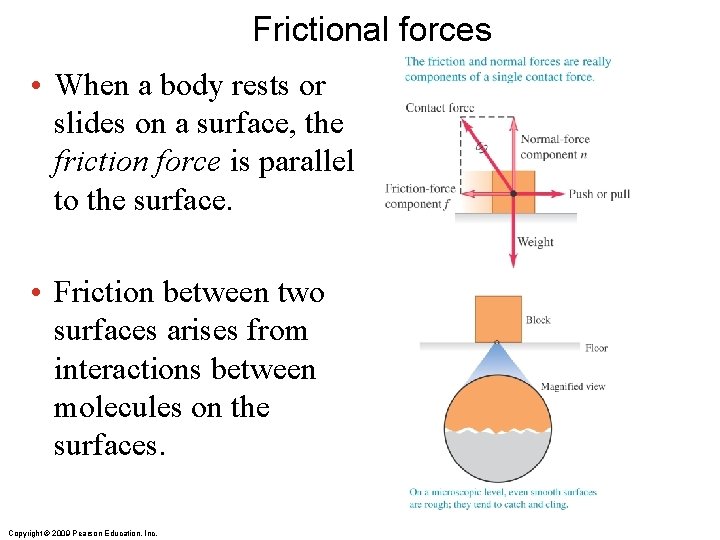

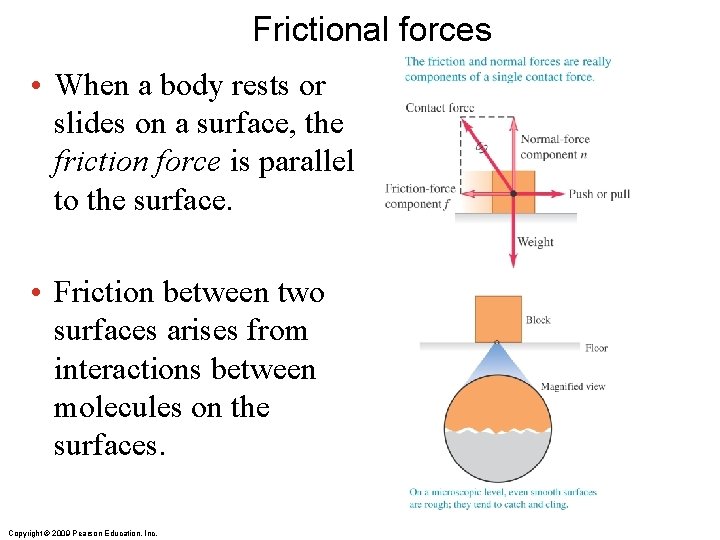

Frictional forces • When a body rests or slides on a surface, the friction force is parallel to the surface. • Friction between two surfaces arises from interactions between molecules on the surfaces. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

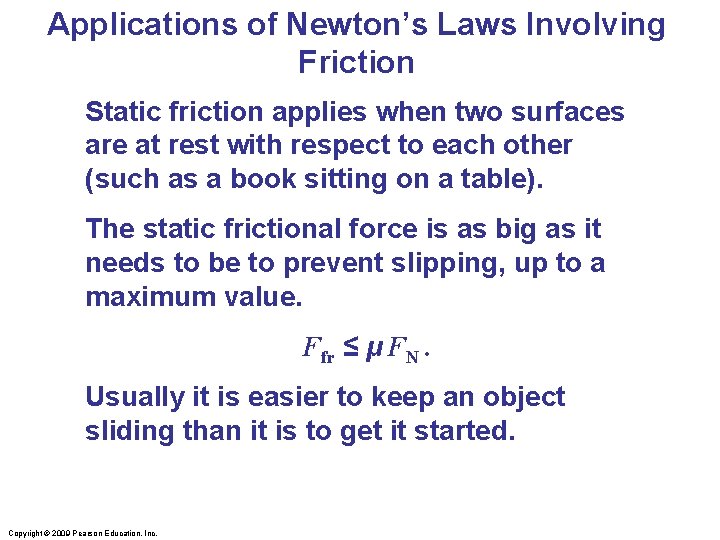

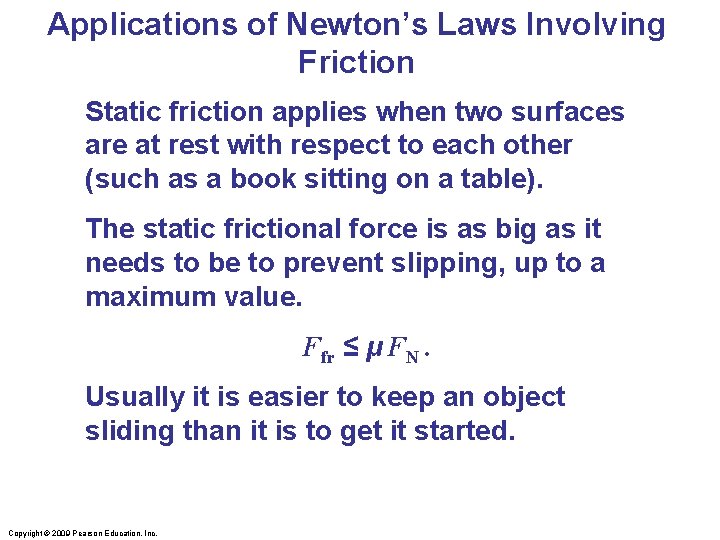

Applications of Newton’s Laws Involving Friction Static friction applies when two surfaces are at rest with respect to each other (such as a book sitting on a table). The static frictional force is as big as it needs to be to prevent slipping, up to a maximum value. Ffr ≤ μ FN. Usually it is easier to keep an object sliding than it is to get it started. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Example: Find the minimum coefficient of friction between surfaces where 25 N is needed to push a 5 kg box. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Example: Find the frictional force holding a 25 kg object in equilibrium at the top of a 150 incline. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

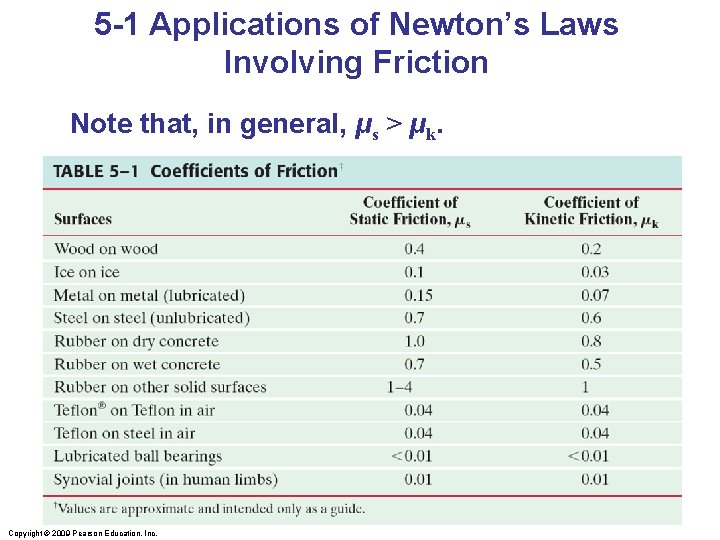

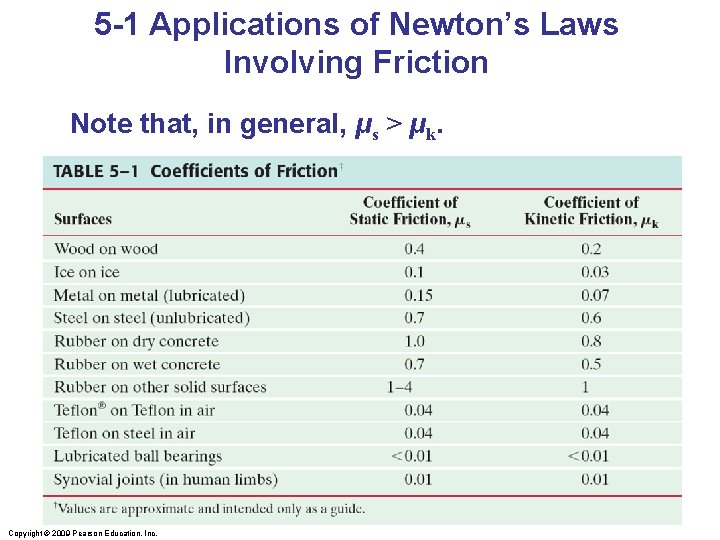

5 -1 Applications of Newton’s Laws Involving Friction Note that, in general, μs > μk. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

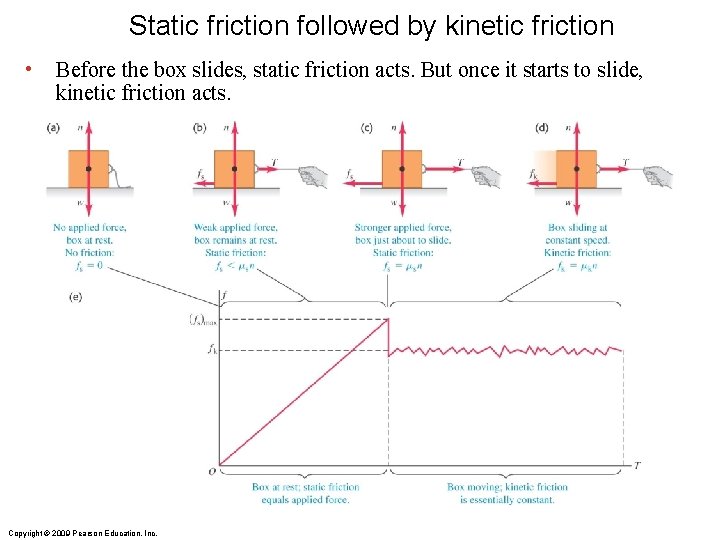

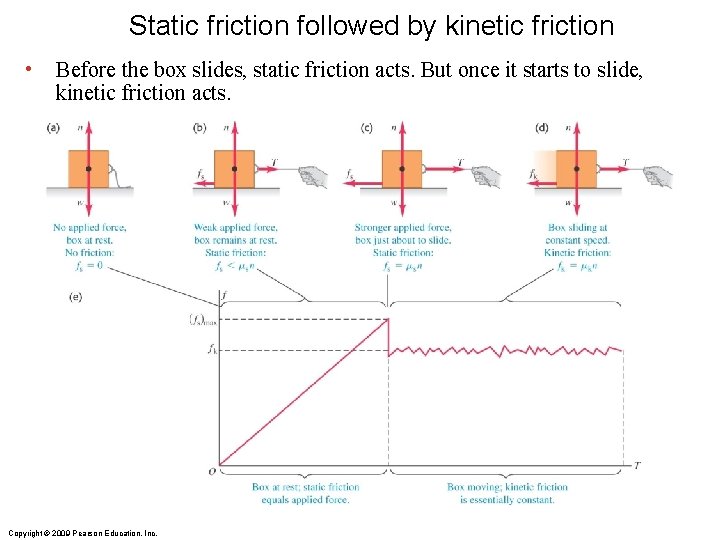

Static friction followed by kinetic friction • Before the box slides, static friction acts. But once it starts to slide, kinetic friction acts. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

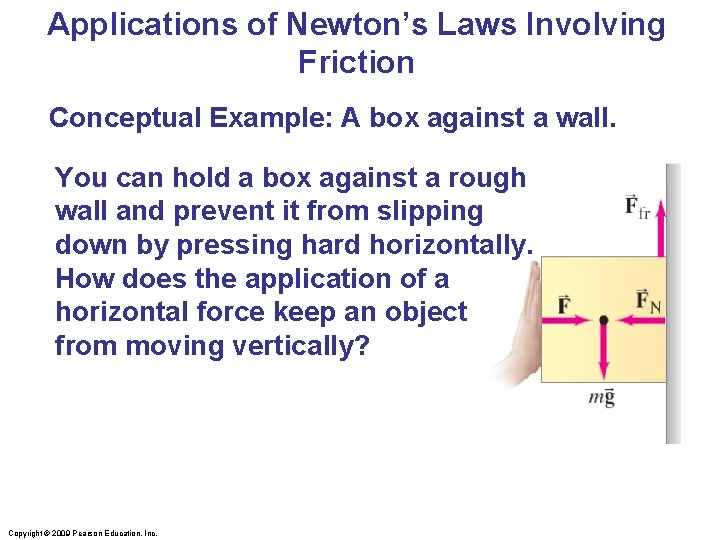

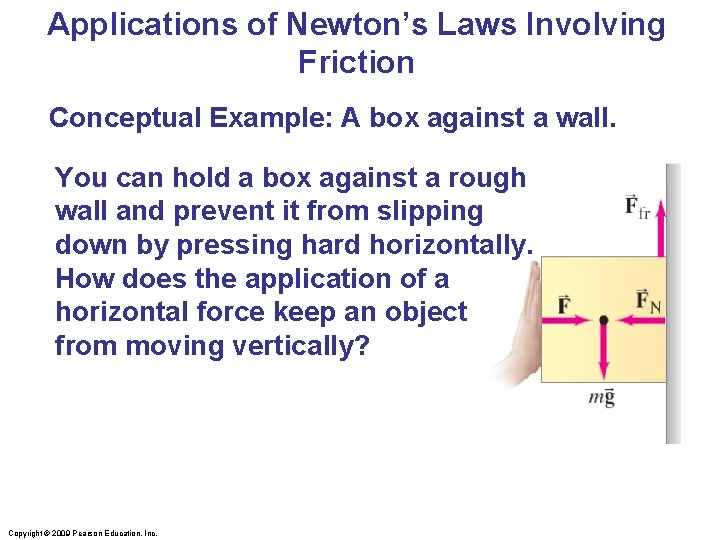

Applications of Newton’s Laws Involving Friction Conceptual Example: A box against a wall. You can hold a box against a rough wall and prevent it from slipping down by pressing hard horizontally. How does the application of a horizontal force keep an object from moving vertically? Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

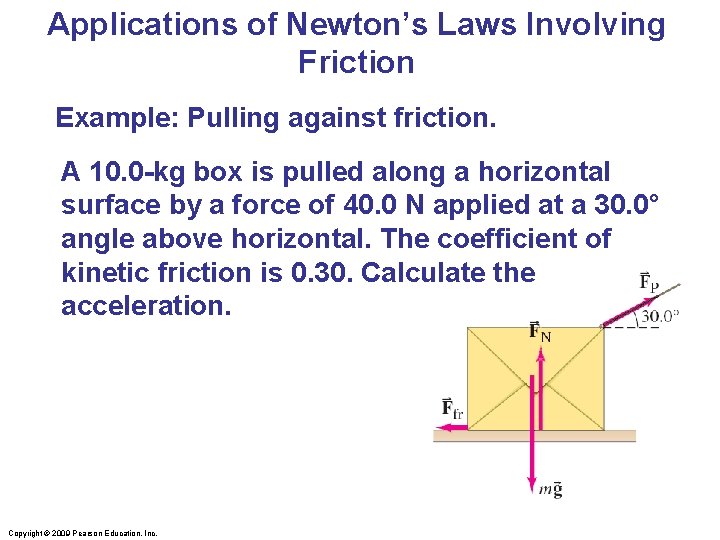

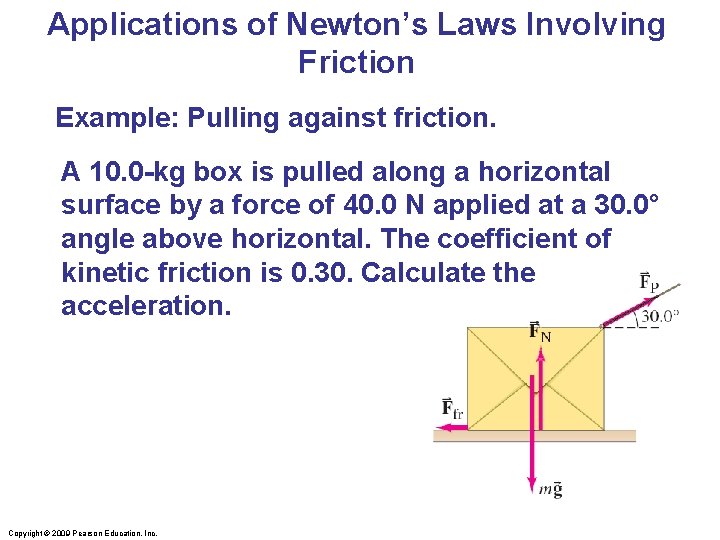

Applications of Newton’s Laws Involving Friction Example: Pulling against friction. A 10. 0 -kg box is pulled along a horizontal surface by a force of 40. 0 N applied at a 30. 0° angle above horizontal. The coefficient of kinetic friction is 0. 30. Calculate the acceleration. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

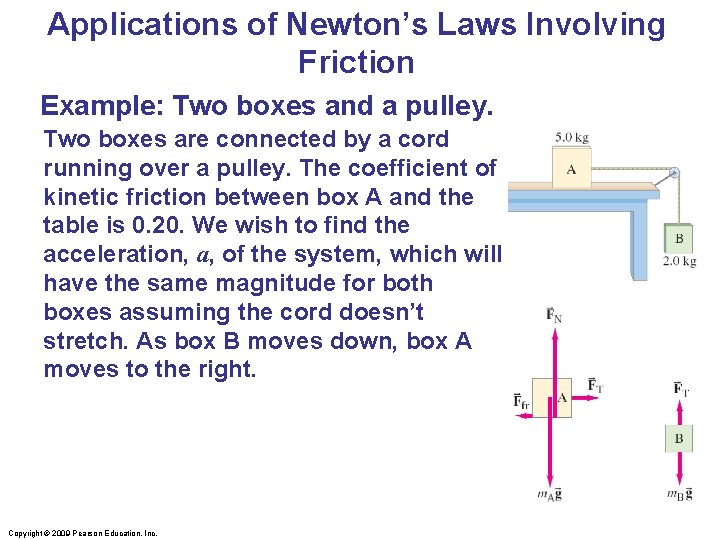

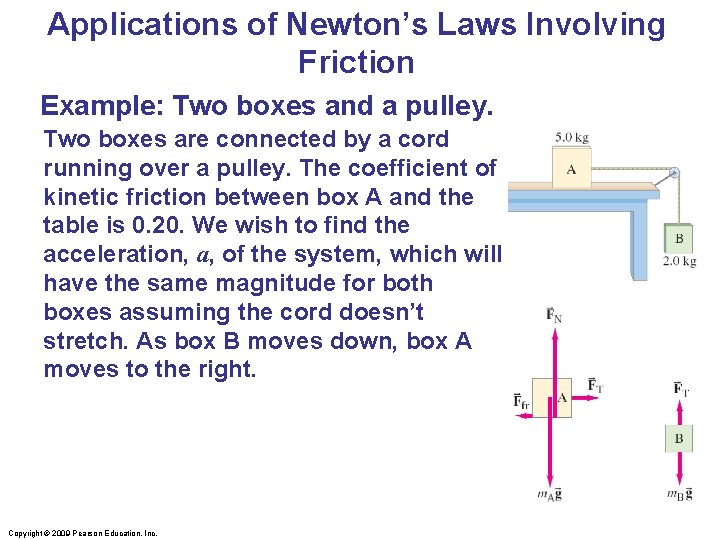

Applications of Newton’s Laws Involving Friction Example: Two boxes and a pulley. Two boxes are connected by a cord running over a pulley. The coefficient of kinetic friction between box A and the table is 0. 20. We wish to find the acceleration, a, of the system, which will have the same magnitude for both boxes assuming the cord doesn’t stretch. As box B moves down, box A moves to the right. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

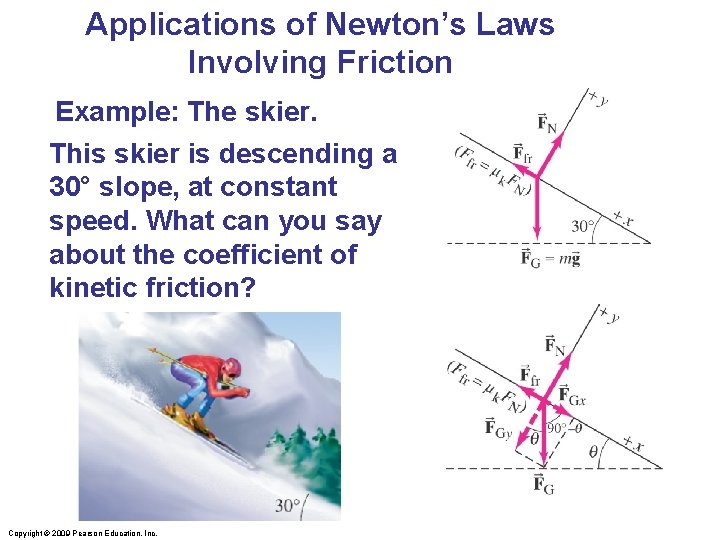

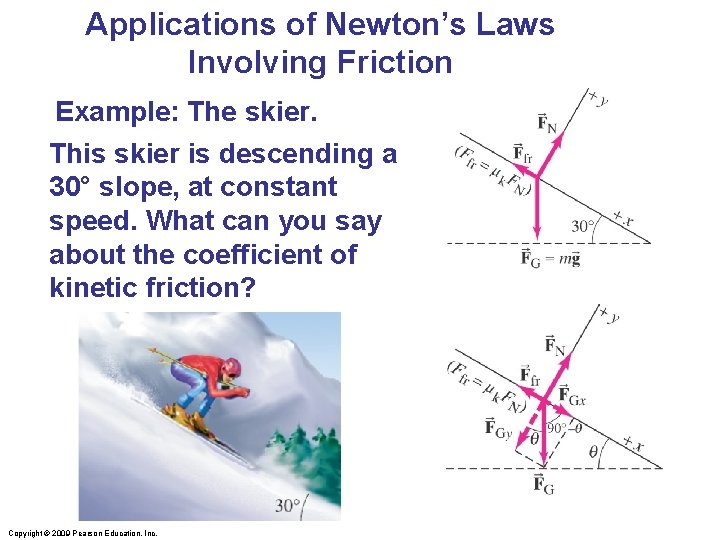

Applications of Newton’s Laws Involving Friction Example: The skier. This skier is descending a 30° slope, at constant speed. What can you say about the coefficient of kinetic friction? Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

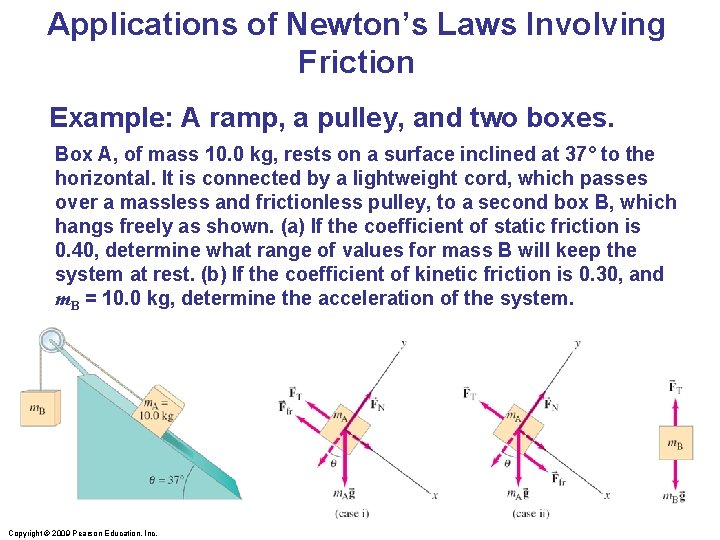

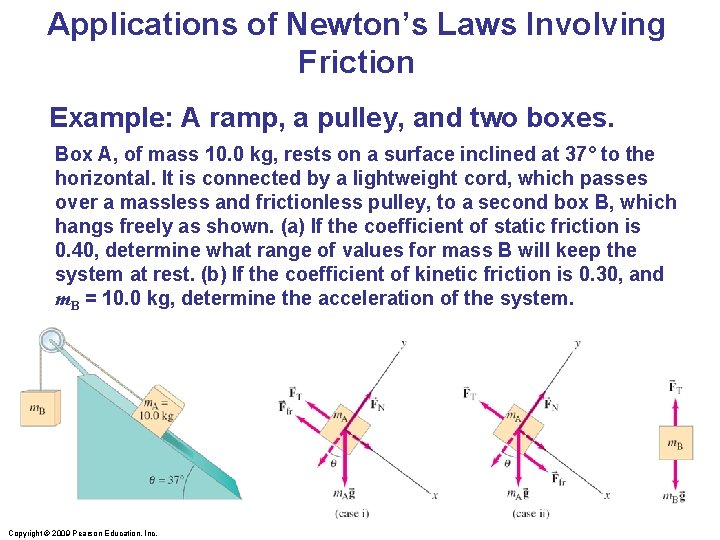

Applications of Newton’s Laws Involving Friction Example: A ramp, a pulley, and two boxes. Box A, of mass 10. 0 kg, rests on a surface inclined at 37° to the horizontal. It is connected by a lightweight cord, which passes over a massless and frictionless pulley, to a second box B, which hangs freely as shown. (a) If the coefficient of static friction is 0. 40, determine what range of values for mass B will keep the system at rest. (b) If the coefficient of kinetic friction is 0. 30, and m. B = 10. 0 kg, determine the acceleration of the system. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

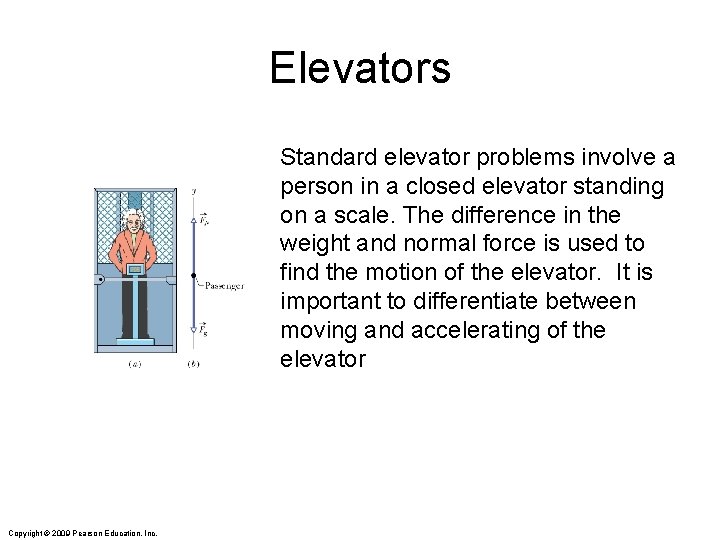

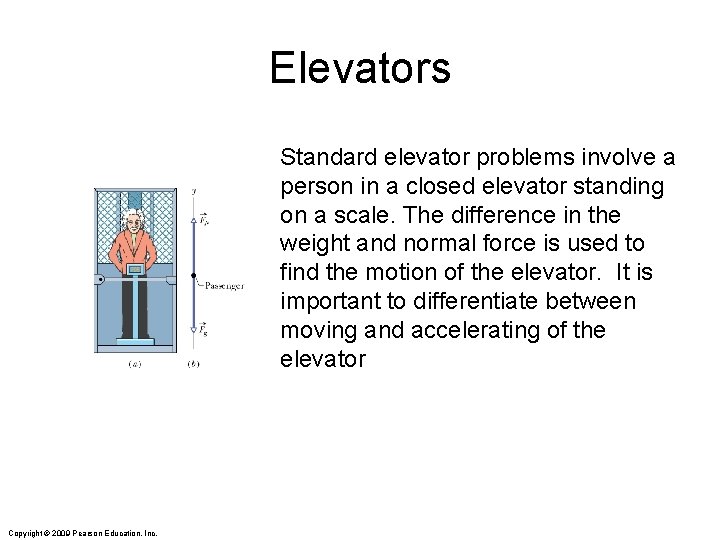

Elevators Standard elevator problems involve a person in a closed elevator standing on a scale. The difference in the weight and normal force is used to find the motion of the elevator. It is important to differentiate between moving and accelerating of the elevator Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Drop Zone Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

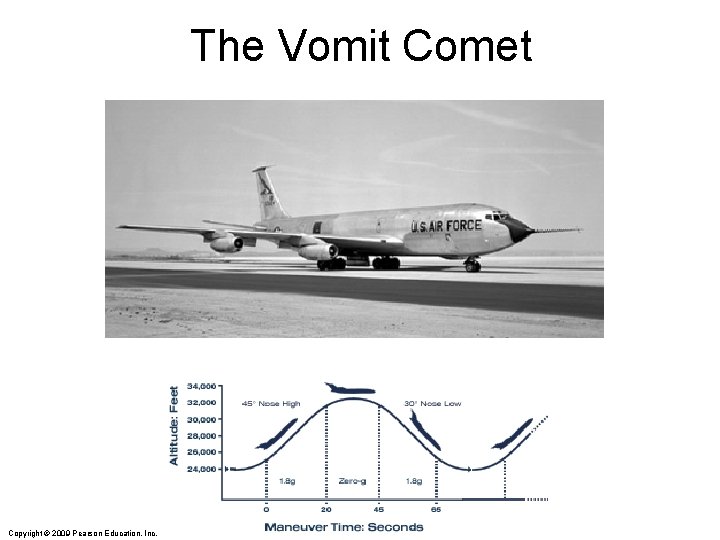

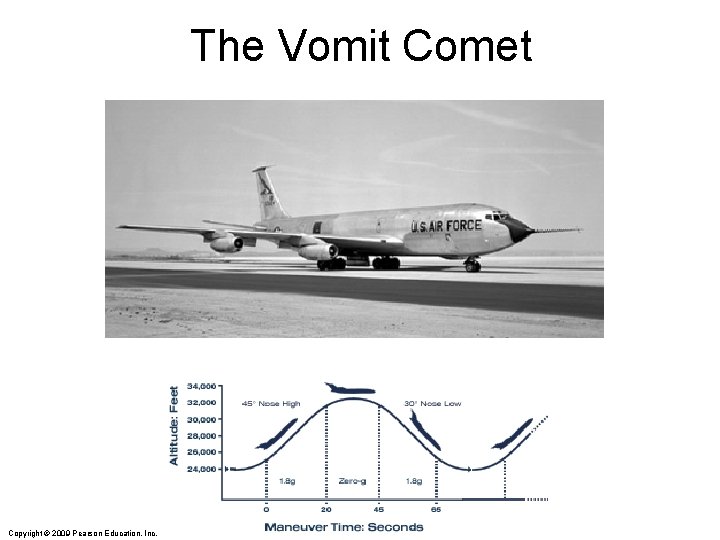

The Vomit Comet Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

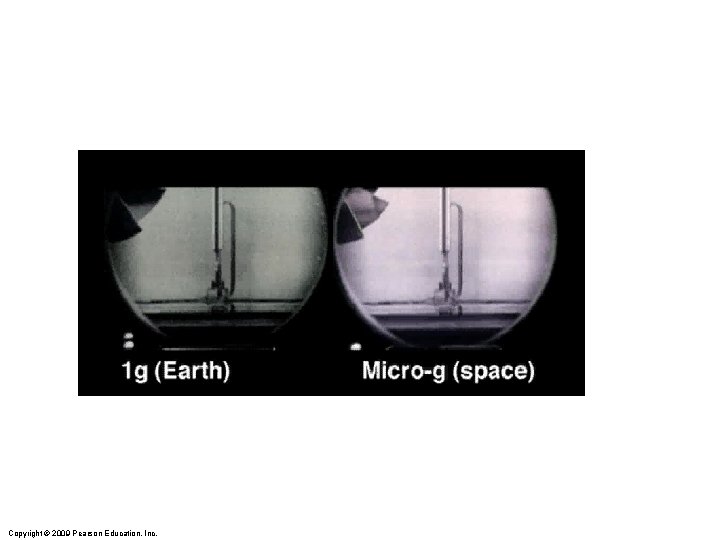

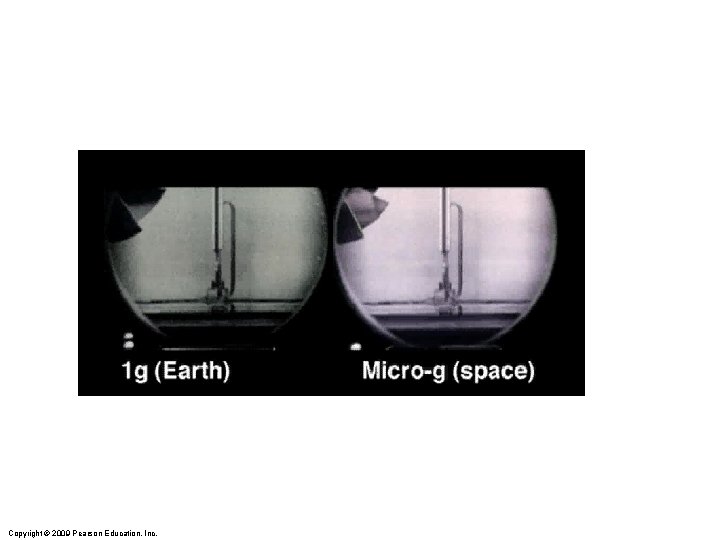

Weightlessness Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

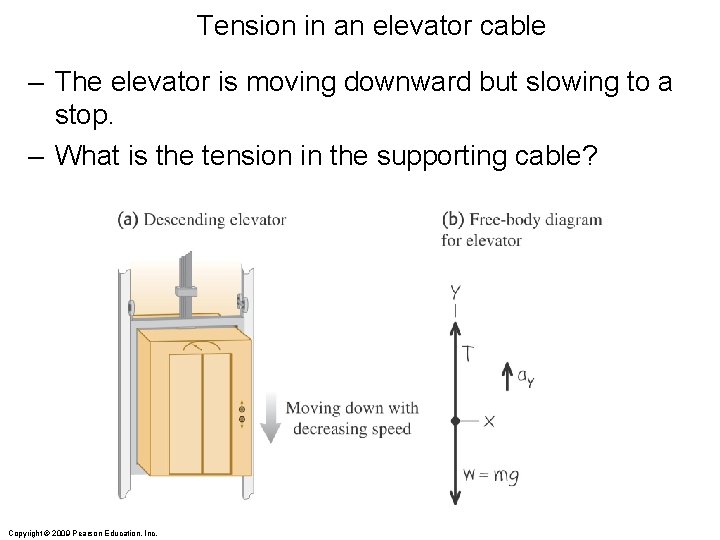

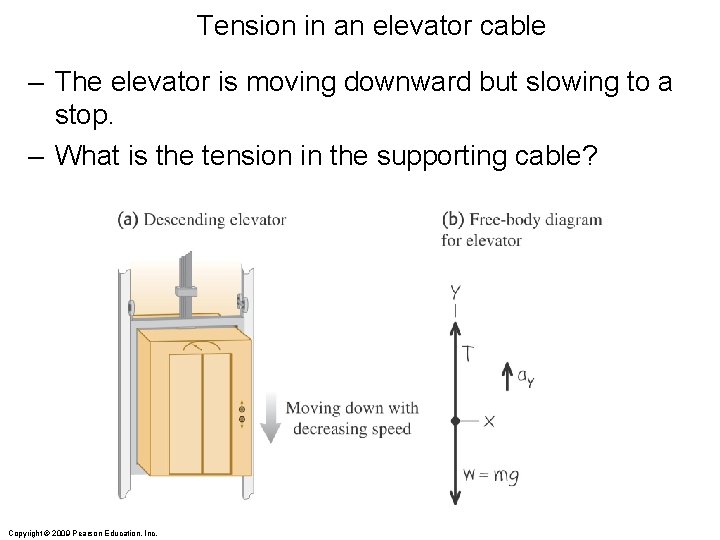

Tension in an elevator cable – The elevator is moving downward but slowing to a stop. – What is the tension in the supporting cable? Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

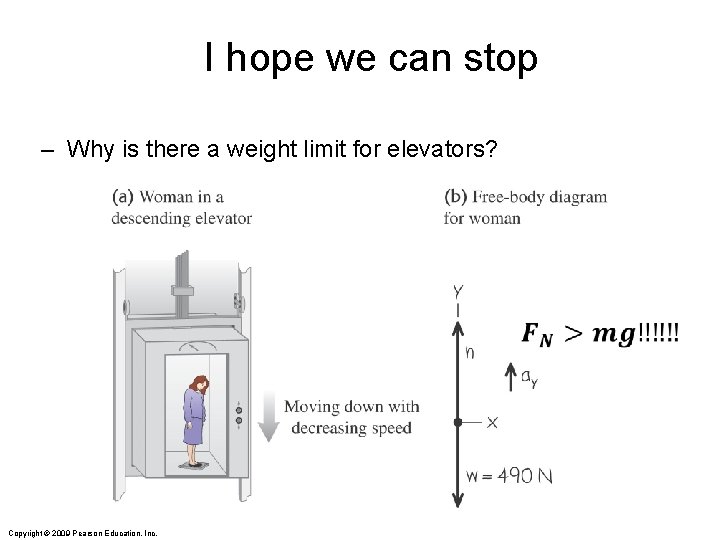

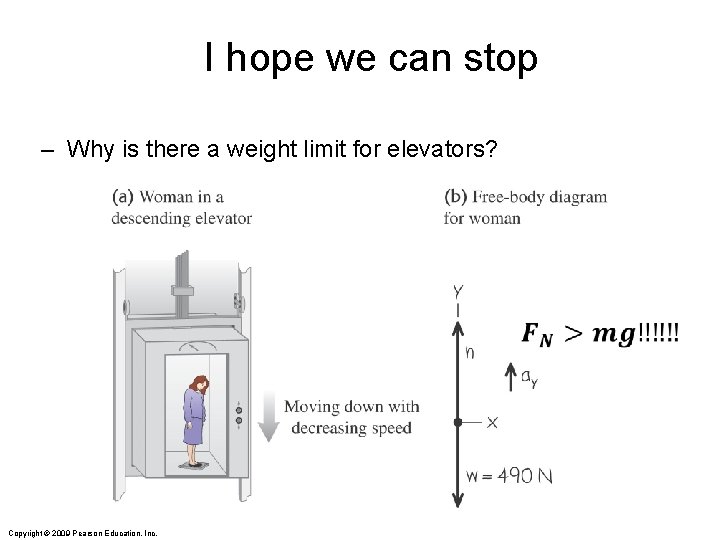

I hope we can stop – Why is there a weight limit for elevators? Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Example: Calculate the acceleration of an elevator in which a 75 kg banana slug feels a normal force of 500 N. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

• Example: A 40 kg child stands on a scale in an elevator that accelerates up at 3 m/s 2. What does the scale read? Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Atwood Machines A natural extension of the elevator problem is the Atwood machine. This is simply a pulley with a mass hanging over each side. It is easy to see that the system will not be in equilibrium if the masses are not the same. We can use free body diagrams and summation of forces to find the acceleration of the system. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Example: An Atwood machine is constructed with a 6 kg mass and a 4 kg mass hanging on opposite sides of a frictionless pulley. Find the acceleration of the 6 kg mass. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

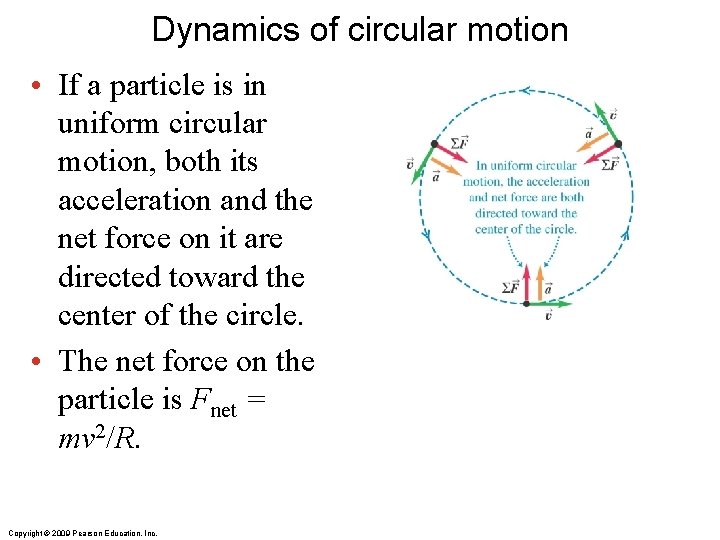

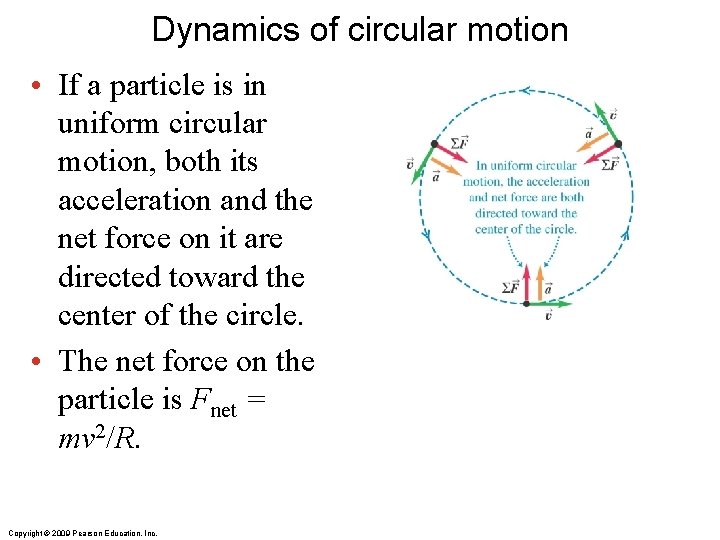

Dynamics of circular motion • If a particle is in uniform circular motion, both its acceleration and the net force on it are directed toward the center of the circle. • The net force on the particle is Fnet = mv 2/R. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

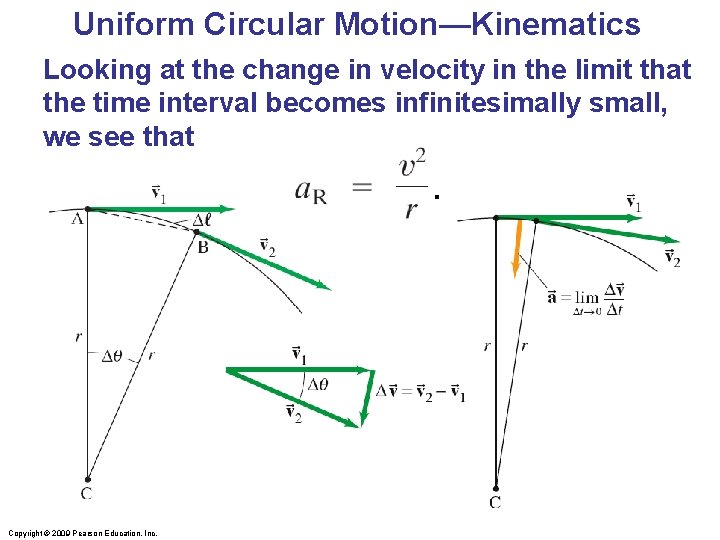

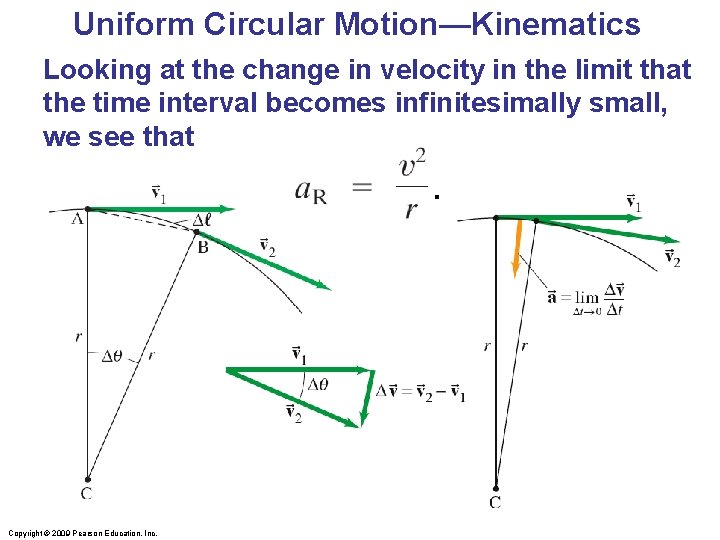

Uniform Circular Motion—Kinematics Looking at the change in velocity in the limit that the time interval becomes infinitesimally small, we see that. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

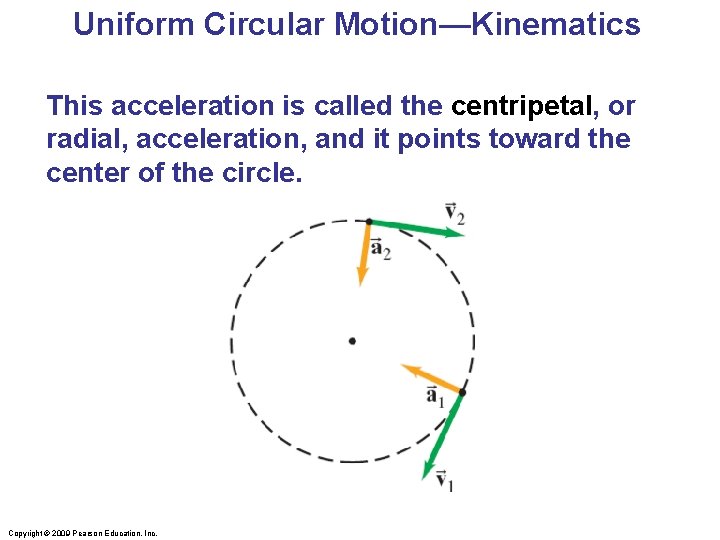

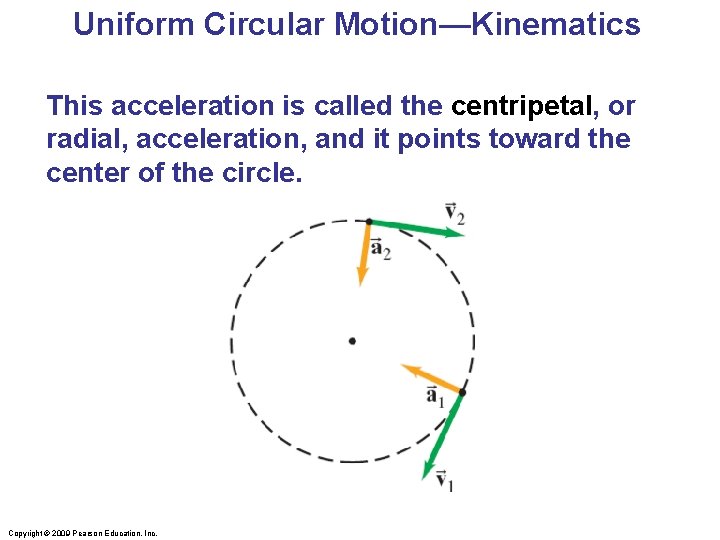

Uniform Circular Motion—Kinematics This acceleration is called the centripetal, or radial, acceleration, and it points toward the center of the circle. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

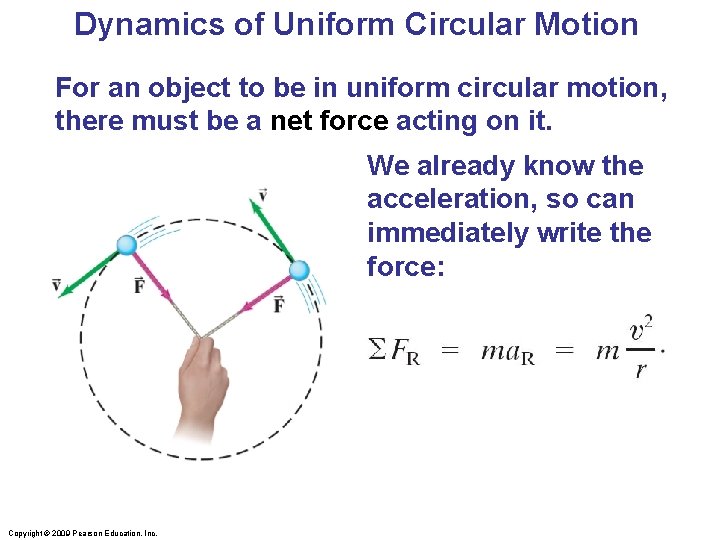

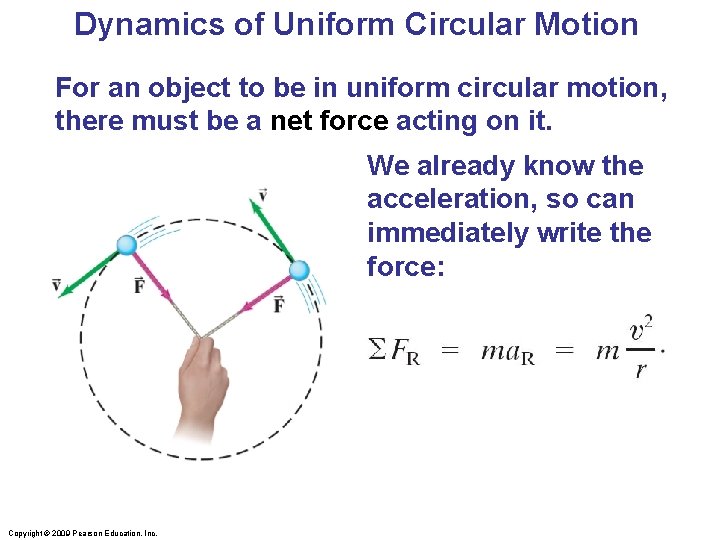

Dynamics of Uniform Circular Motion For an object to be in uniform circular motion, there must be a net force acting on it. We already know the acceleration, so can immediately write the force: Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

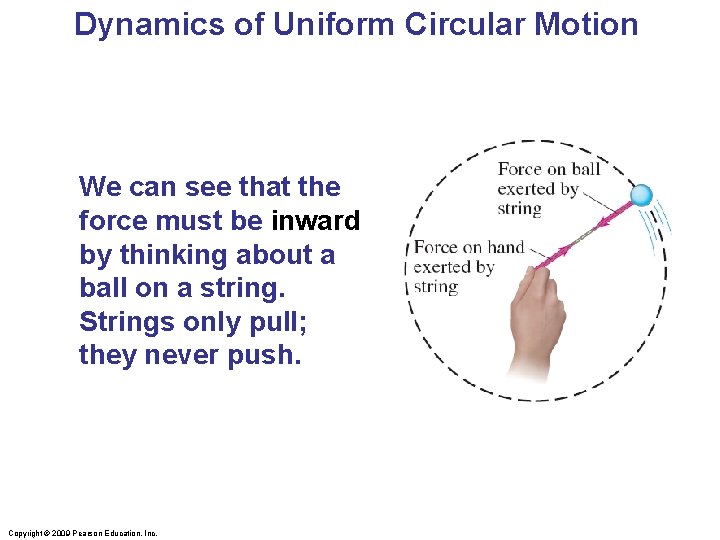

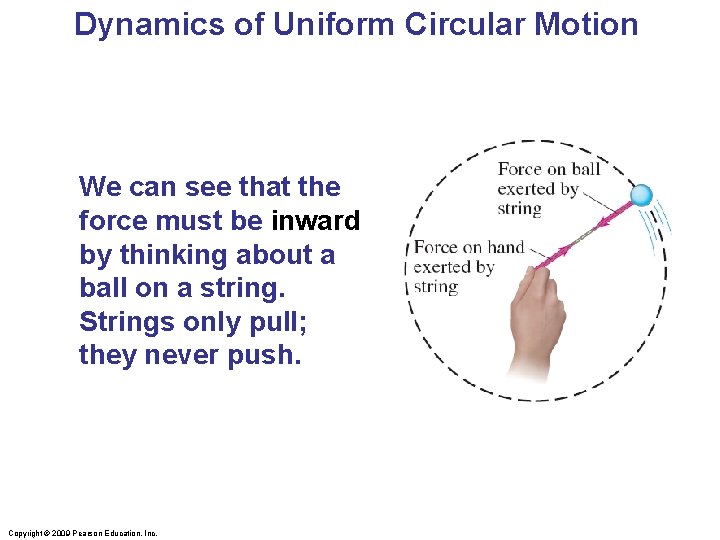

Dynamics of Uniform Circular Motion We can see that the force must be inward by thinking about a ball on a string. Strings only pull; they never push. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

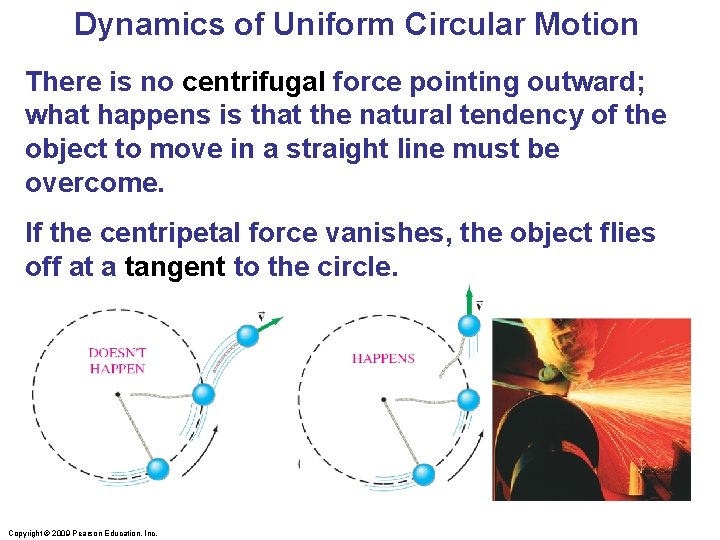

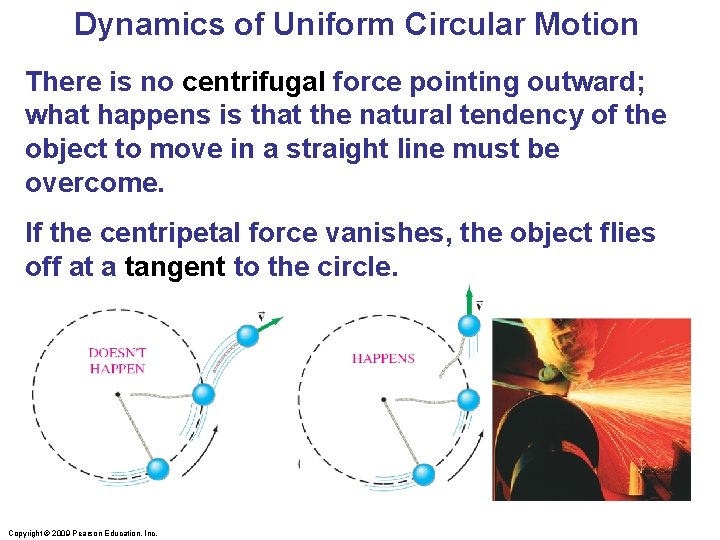

Dynamics of Uniform Circular Motion There is no centrifugal force pointing outward; what happens is that the natural tendency of the object to move in a straight line must be overcome. If the centripetal force vanishes, the object flies off at a tangent to the circle. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Uniform Circular Motion—Kinematics Example: Calculate the centripetal force needed to make a 20 kg mass move in a 3 m circle at 15 m/s. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Uniform Circular Motion—Kinematics Example: Find the tension in a 1. 3 m string used to swing a 2 kg mass in a horizontal circle at 6 m/s. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

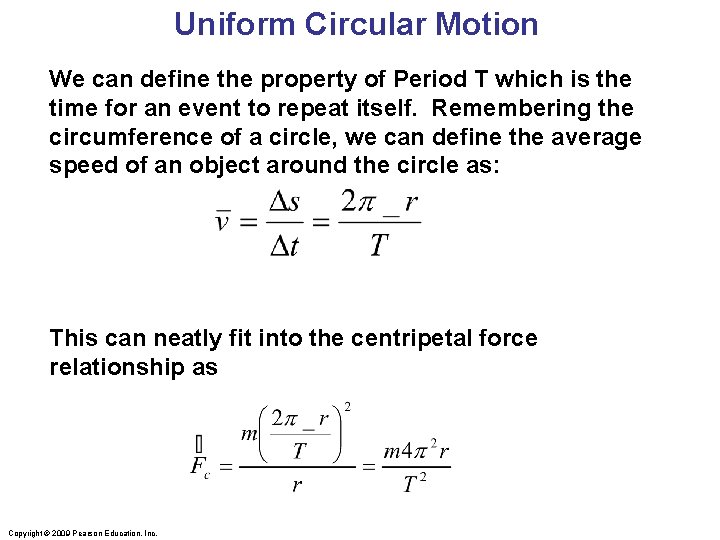

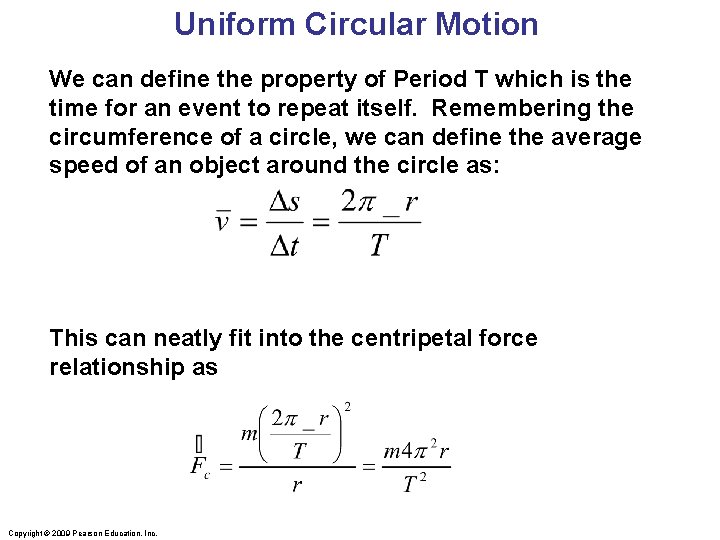

Uniform Circular Motion We can define the property of Period T which is the time for an event to repeat itself. Remembering the circumference of a circle, we can define the average speed of an object around the circle as: This can neatly fit into the centripetal force relationship as Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Example: A record player spins at 33 rpm. Find the friction required to keep a 100 g mass on the turntable 15 cm from the center. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

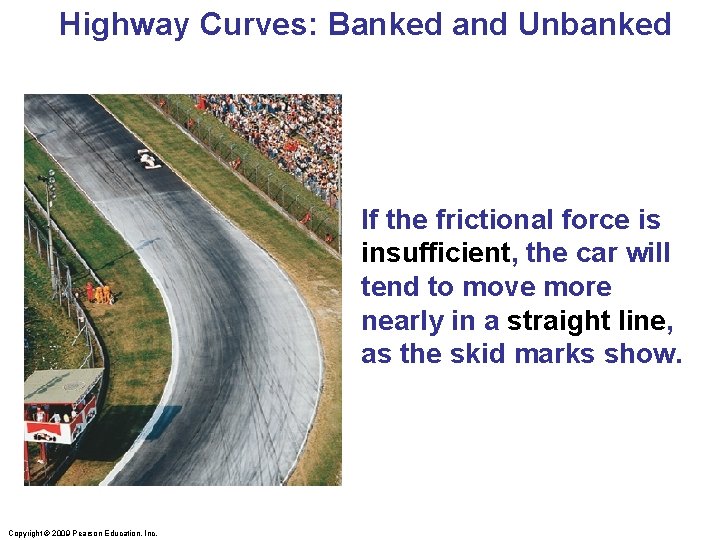

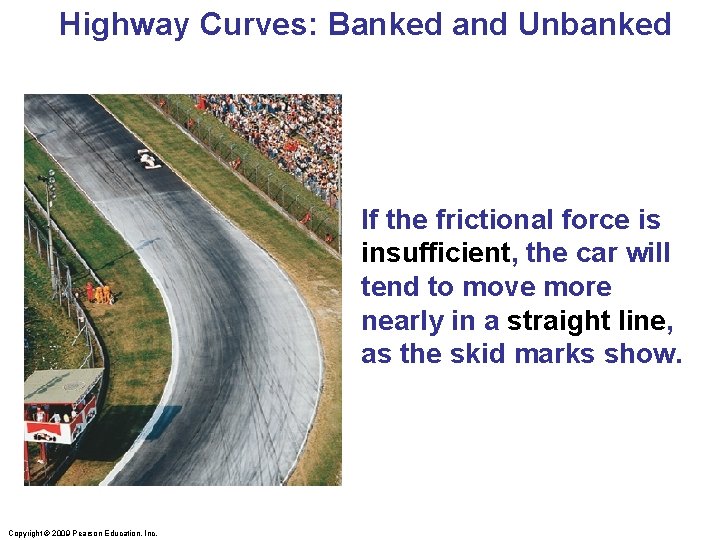

Highway Curves: Banked and Unbanked If the frictional force is insufficient, the car will tend to move more nearly in a straight line, as the skid marks show. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

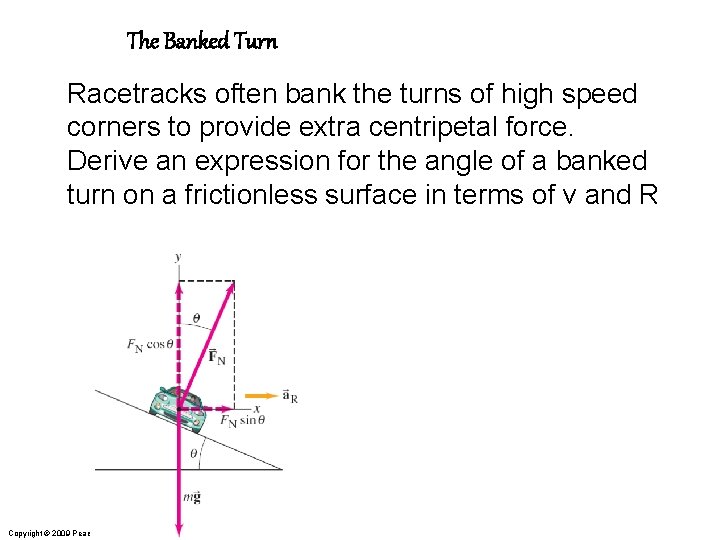

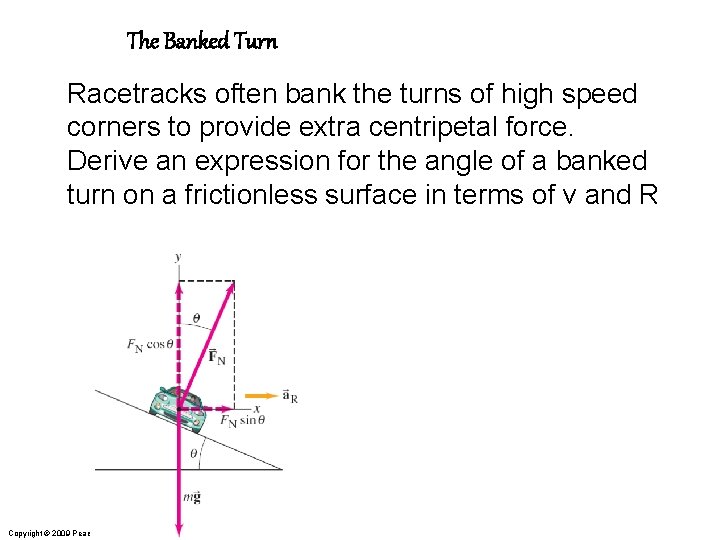

The Banked Turn Racetracks often bank the turns of high speed corners to provide extra centripetal force. Derive an expression for the angle of a banked turn on a frictionless surface in terms of v and R Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Example: At what angle should a racetrack be banked if cars can take a 500 m radius turn at 50 m/s without friction? Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

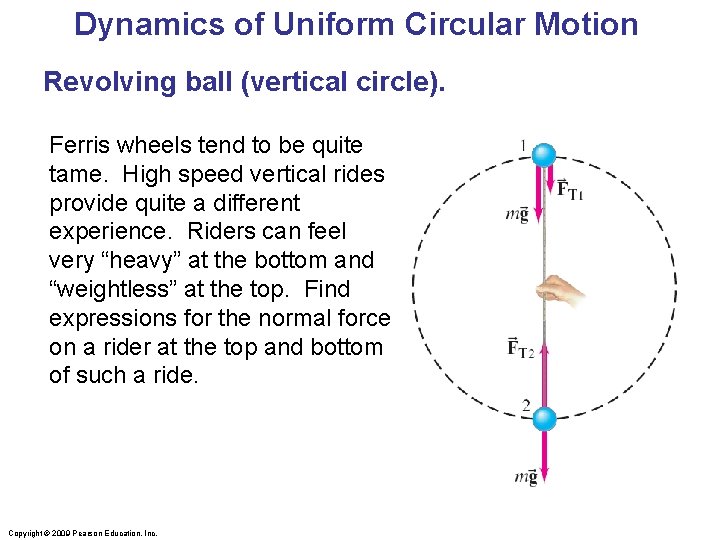

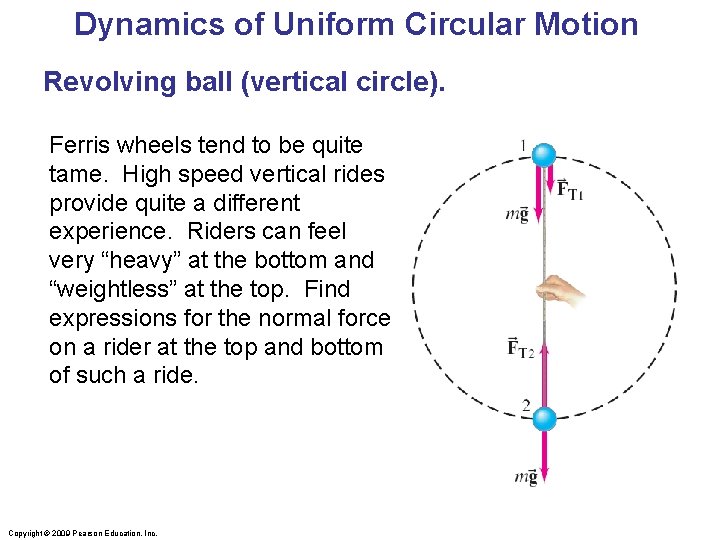

Dynamics of Uniform Circular Motion Revolving ball (vertical circle). Ferris wheels tend to be quite tame. High speed vertical rides provide quite a different experience. Riders can feel very “heavy” at the bottom and “weightless” at the top. Find expressions for the normal force on a rider at the top and bottom of such a ride. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

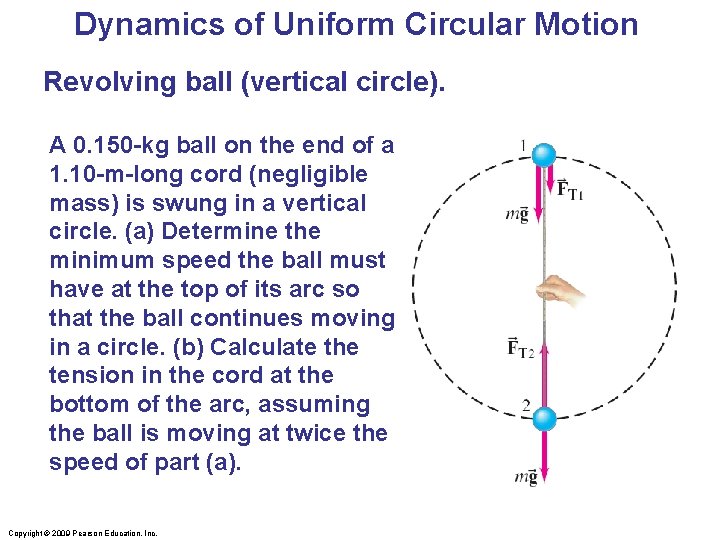

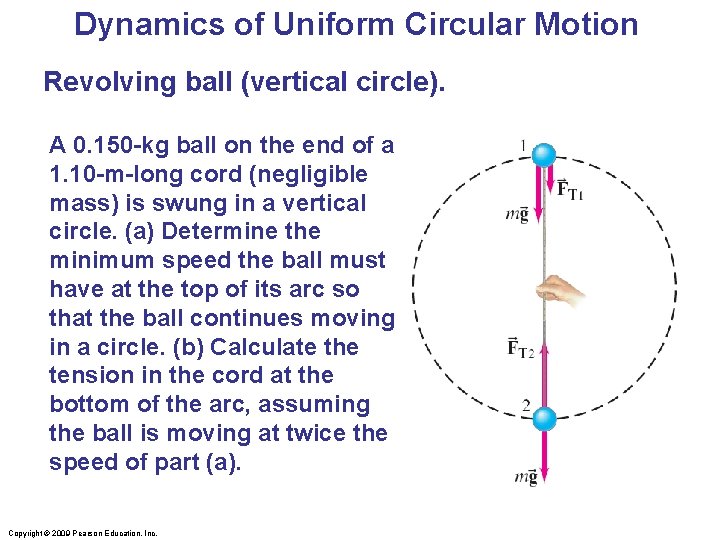

Dynamics of Uniform Circular Motion Revolving ball (vertical circle). A 0. 150 -kg ball on the end of a 1. 10 -m-long cord (negligible mass) is swung in a vertical circle. (a) Determine the minimum speed the ball must have at the top of its arc so that the ball continues moving in a circle. (b) Calculate the tension in the cord at the bottom of the arc, assuming the ball is moving at twice the speed of part (a). Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

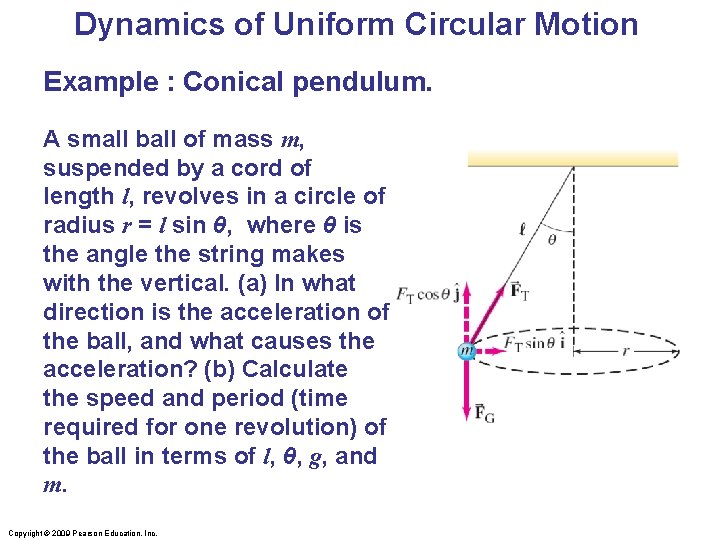

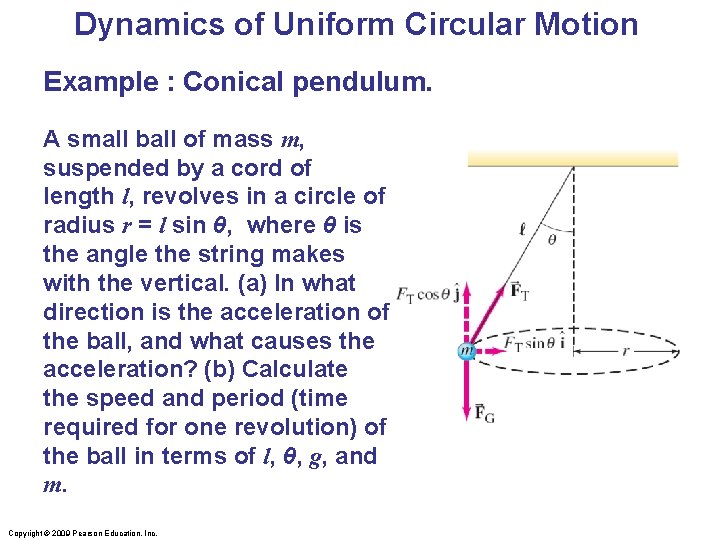

Dynamics of Uniform Circular Motion Example : Conical pendulum. A small ball of mass m, suspended by a cord of length l, revolves in a circle of radius r = l sin θ, where θ is the angle the string makes with the vertical. (a) In what direction is the acceleration of the ball, and what causes the acceleration? (b) Calculate the speed and period (time required for one revolution) of the ball in terms of l, θ, g, and m. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

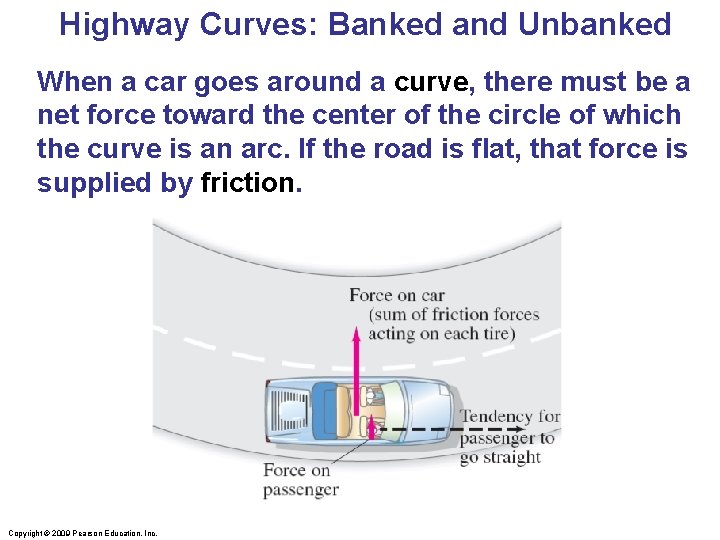

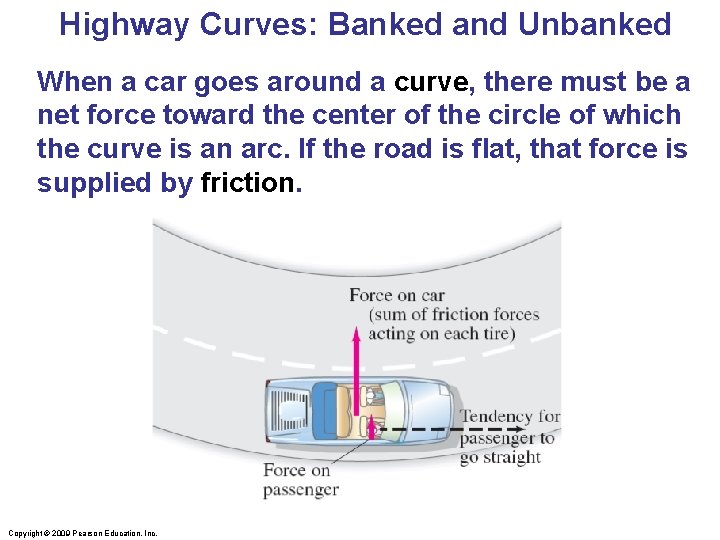

Highway Curves: Banked and Unbanked When a car goes around a curve, there must be a net force toward the center of the circle of which the curve is an arc. If the road is flat, that force is supplied by friction. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

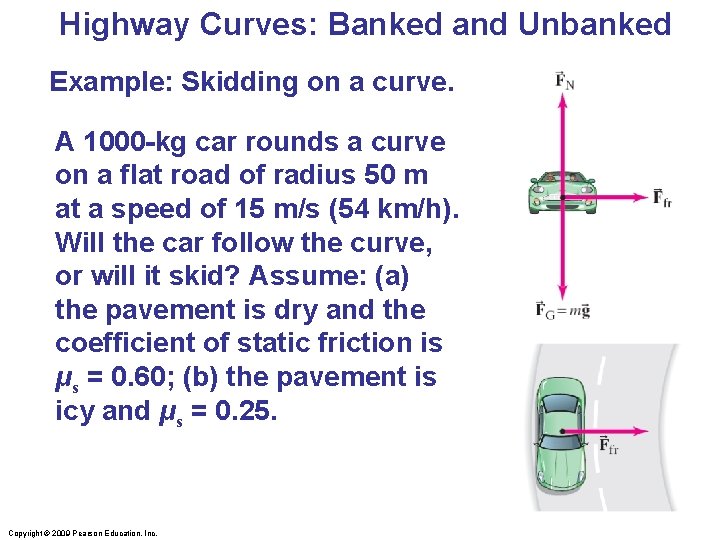

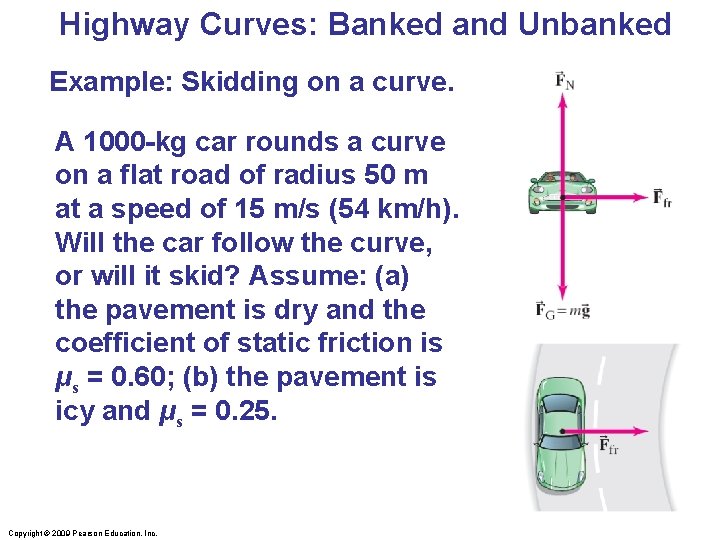

Highway Curves: Banked and Unbanked Example: Skidding on a curve. A 1000 -kg car rounds a curve on a flat road of radius 50 m at a speed of 15 m/s (54 km/h). Will the car follow the curve, or will it skid? Assume: (a) the pavement is dry and the coefficient of static friction is μs = 0. 60; (b) the pavement is icy and μs = 0. 25. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

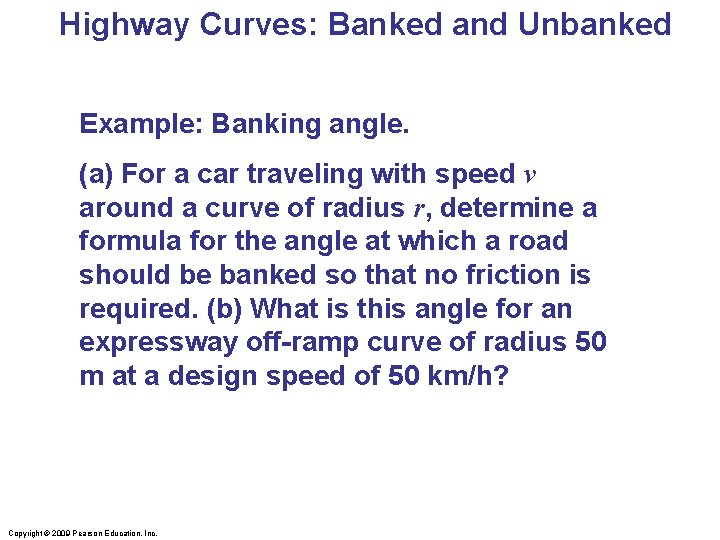

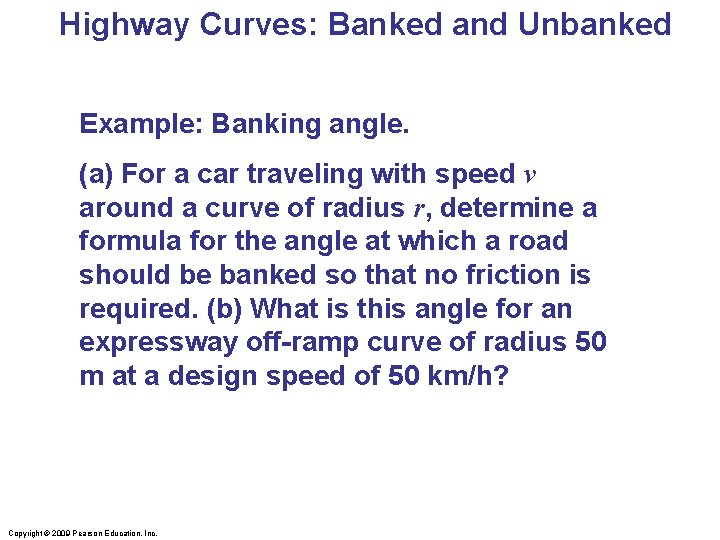

Highway Curves: Banked and Unbanked Example: Banking angle. (a) For a car traveling with speed v around a curve of radius r, determine a formula for the angle at which a road should be banked so that no friction is required. (b) What is this angle for an expressway off-ramp curve of radius 50 m at a design speed of 50 km/h? Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

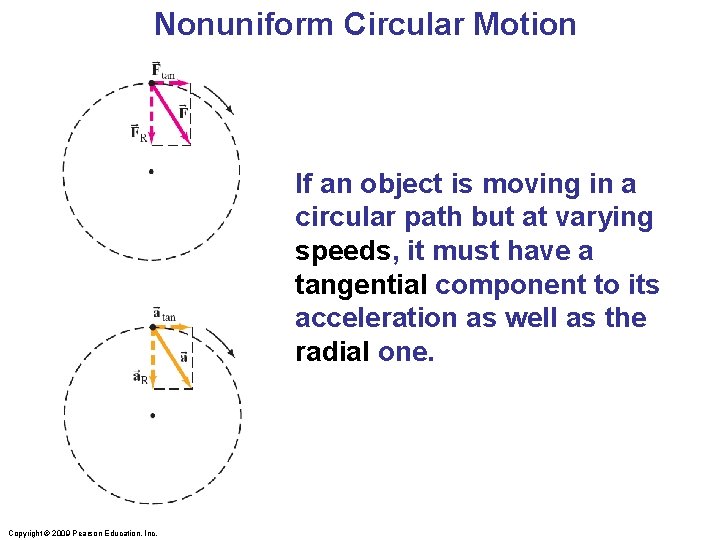

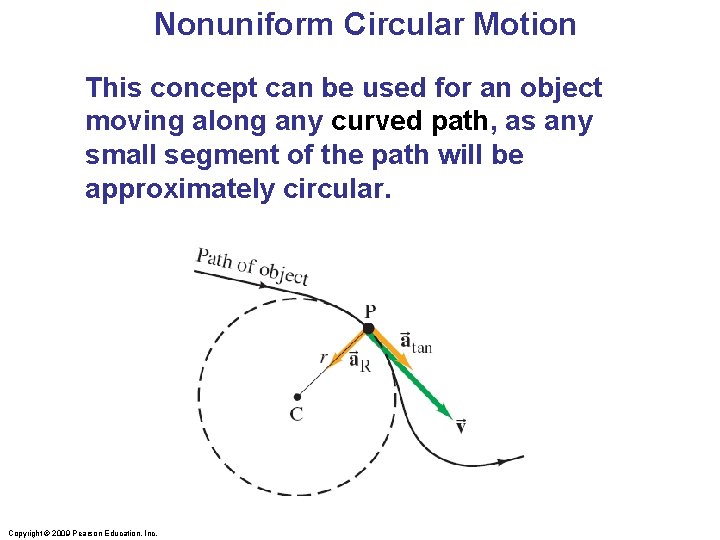

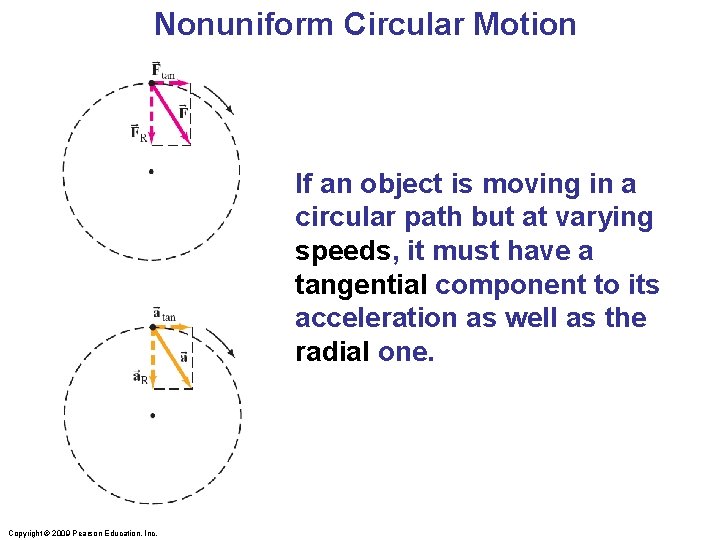

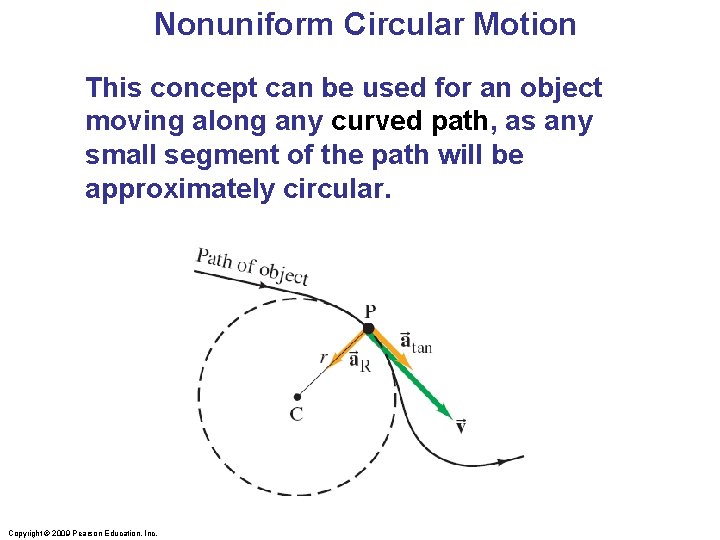

Nonuniform Circular Motion If an object is moving in a circular path but at varying speeds, it must have a tangential component to its acceleration as well as the radial one. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Nonuniform Circular Motion This concept can be used for an object moving along any curved path, as any small segment of the path will be approximately circular. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

Velocity-Dependent Forces: Drag and Terminal Velocity When an object moves through a fluid, it experiences a drag force that depends on the velocity of the object. For small velocities, the force is approximately proportional to the velocity; for higher speeds, the force is approximately proportional to the square of the velocity. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

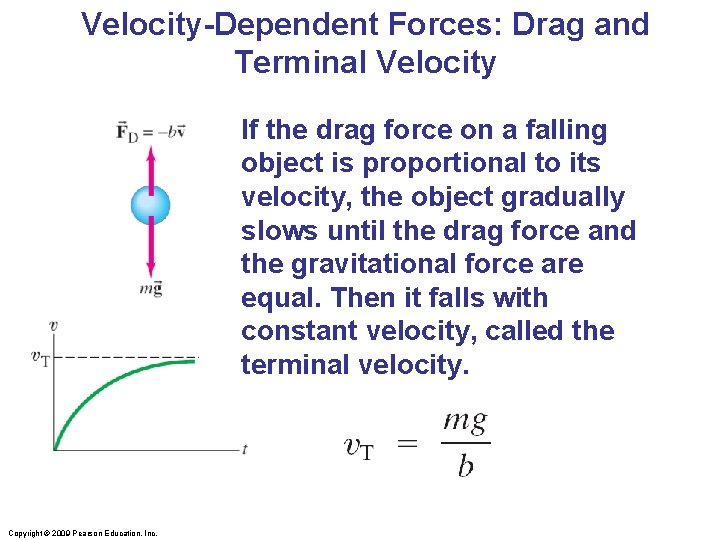

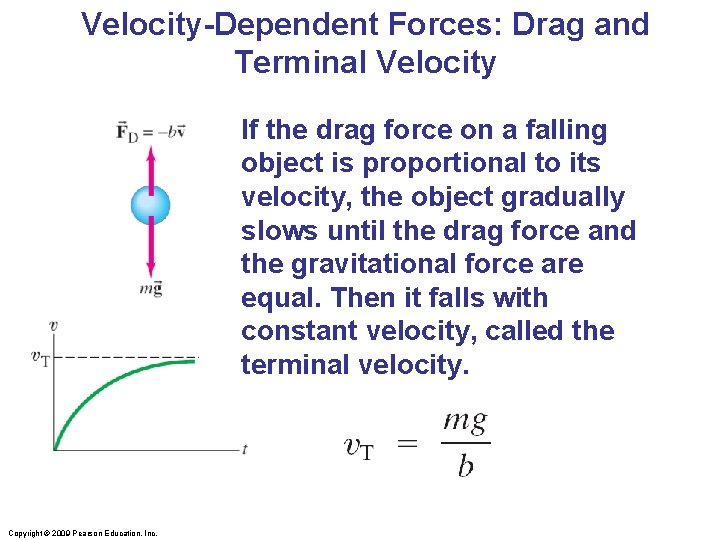

Velocity-Dependent Forces: Drag and Terminal Velocity If the drag force on a falling object is proportional to its velocity, the object gradually slows until the drag force and the gravitational force are equal. Then it falls with constant velocity, called the terminal velocity. Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.

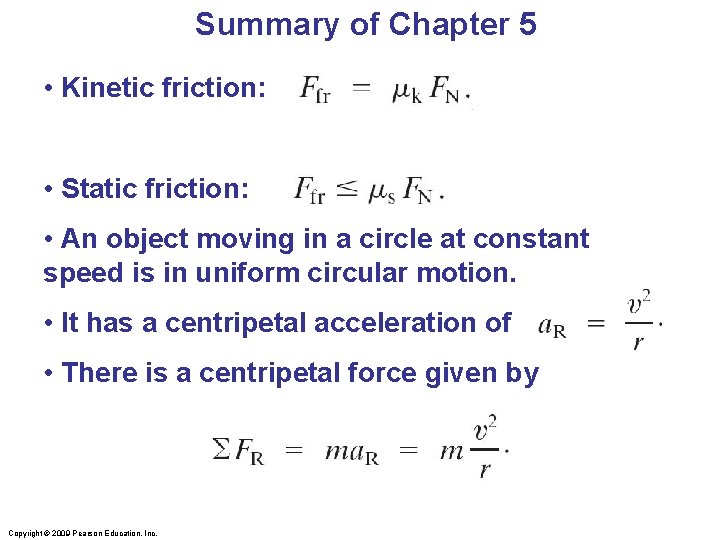

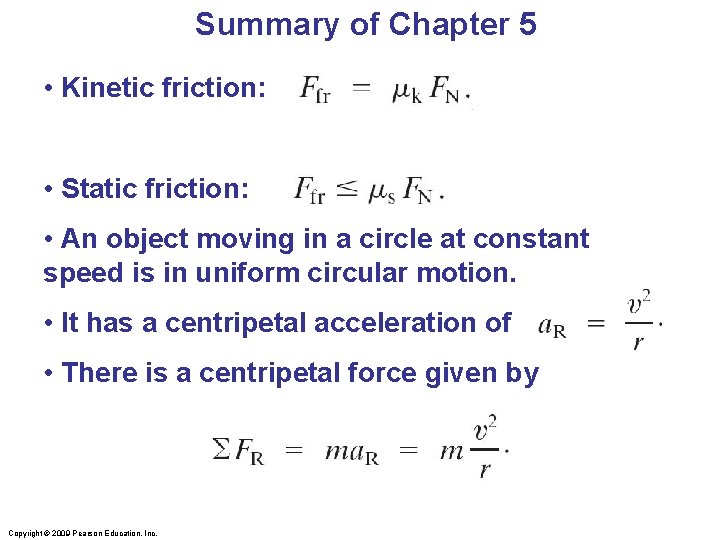

Summary of Chapter 5 • Kinetic friction: • Static friction: • An object moving in a circle at constant speed is in uniform circular motion. • It has a centripetal acceleration of • There is a centripetal force given by Copyright © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc.