Using multidimensional analysis to explore possible universal patterns

Using multi-dimensional analysis to explore possible universal patterns of register variation Doug Biber

Outline of the talk A. Introduce the Biber and Conrad (2009) framework for analyses of registers and register variation B. Discuss methodological problems for cross domain and cross linguistic analyses of register variation C. Present Multi Dimensional (MD) Analysis as an approach that can address those methodological problems – – – Briefly introduce the goals and methods of MD Analysis (Biber, 1988) Survey MD studies of different discourse domains in English Survey MD studies of register variation in other languages D. Twin research generalizations: 1) – Possible ‘universal’ dimensions of register variation Especially the ‘oral’ versus ‘literate’ dimension of variation • – 2) Regardless of discourse domain Also narrative discourse and stance Dimensions of register variation that are unique to each language

Defining characteristics of registers, genres, and styles [From Biber and Conrad (2009), Register, Genre, and Style. Cambridge Univ Press] Defining characteristic Register Genre Style Corpus sample of text excerpts complete texts sample of text excerpts Linguistic characteristics potentially any lexicogrammatical feature specialized expressions, rhetorical organization, formatting any lexico-grammatical feature Distribution of linguistic characteristics frequent and pervasive in texts usually once-occurring in the text, in a particular place in the text frequent and pervasive in texts from the variety Interpretation features are frequent because they serve communicative functions features are conventionally associated with the genre: the expected format, but often not functional features are not directly functional; they are preferred because they are aesthetically valued

Major components in a register analysis SITUATIONAL characteristics Frequent LINGUISTIC features FUNCTION

Analytical goals of (cross linguistic) studies of register variation • Linguistic: Identify the lexico grammatical similarities and differences between two registers, or among a set of multiple registers • Quantitative: Describe the extent of linguistic differences • Interpretive: Describe the functional correlates of observed linguistic differences • Cross linguistic: Do registers vary along similar linguistic parameters, and do they differ to similar extents?

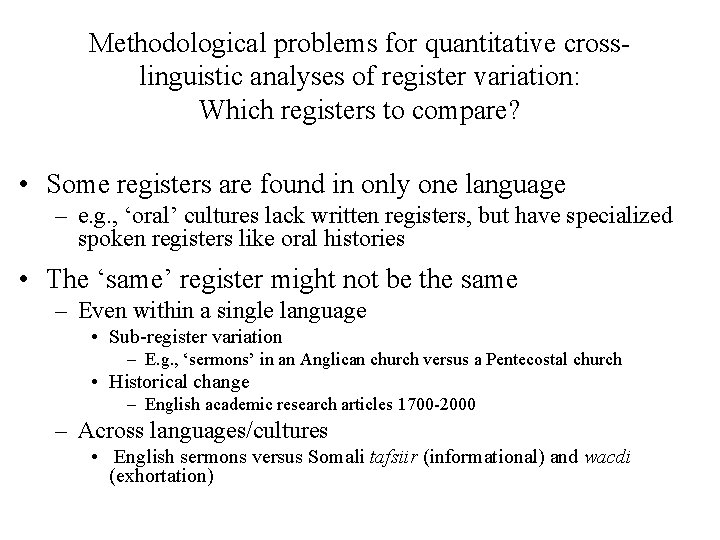

Methodological problems for quantitative cross linguistic analyses of register variation: Which registers to compare? • Some registers are found in only one language – e. g. , ‘oral’ cultures lack written registers, but have specialized spoken registers like oral histories • The ‘same’ register might not be the same – Even within a single language • Sub register variation – E. g. , ‘sermons’ in an Anglican church versus a Pentecostal church • Historical change – English academic research articles 1700 2000 – Across languages/cultures • English sermons versus Somali tafsiir (informational) and wacdi (exhortation)

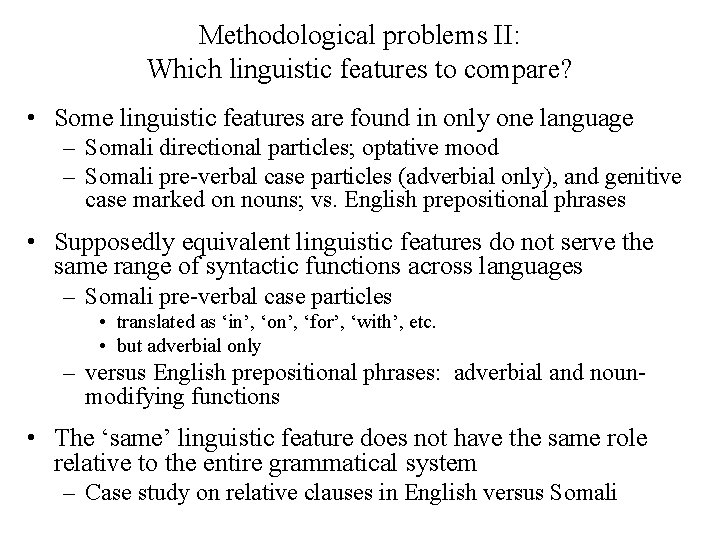

Methodological problems II: Which linguistic features to compare? • Some linguistic features are found in only one language – Somali directional particles; optative mood – Somali pre verbal case particles (adverbial only), and genitive case marked on nouns; vs. English prepositional phrases • Supposedly equivalent linguistic features do not serve the same range of syntactic functions across languages – Somali pre verbal case particles • translated as ‘in’, ‘on’, ‘for’, ‘with’, etc. • but adverbial only – versus English prepositional phrases: adverbial and noun modifying functions • The ‘same’ linguistic feature does not have the same role relative to the entire grammatical system – Case study on relative clauses in English versus Somali

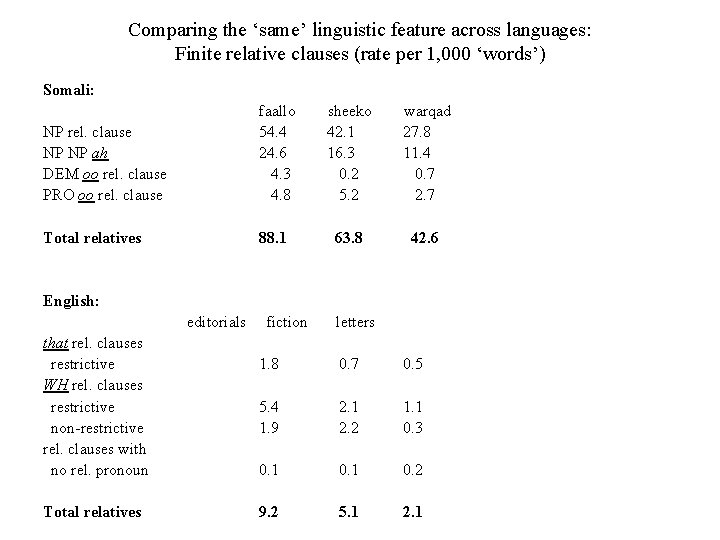

Comparing the ‘same’ linguistic feature across languages: Finite relative clauses (rate per 1, 000 ‘words’) Somali: NP rel. clause NP NP ah DEM oo rel. clause PRO oo rel. clause faallo 54. 4 24. 6 4. 3 4. 8 sheeko 42. 1 16. 3 0. 2 5. 2 warqad 27. 8 11. 4 0. 7 2. 7 Total relatives 88. 1 63. 8 42. 6 English: editorials that rel. clauses restrictive WH rel. clauses restrictive non restrictive rel. clauses with no rel. pronoun Total relatives fiction letters 1. 8 0. 7 0. 5 5. 4 1. 9 2. 1 2. 2 1. 1 0. 3 0. 1 0. 2 9. 2 5. 1 2. 1

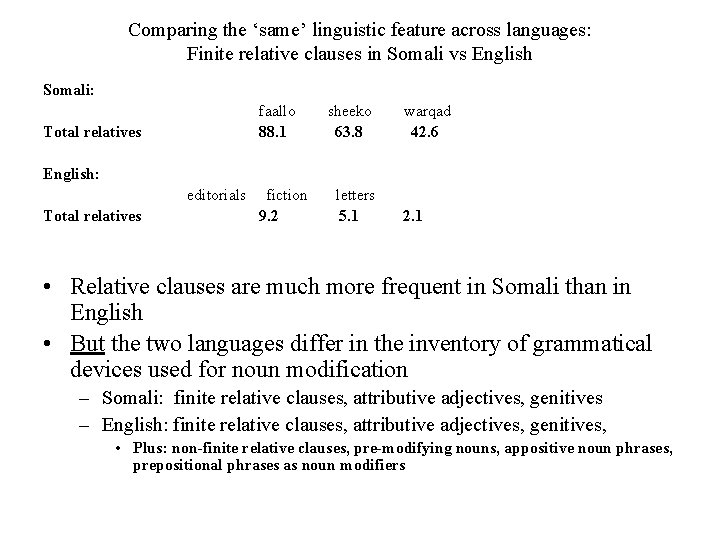

Comparing the ‘same’ linguistic feature across languages: Finite relative clauses in Somali vs English Somali: faallo 88. 1 Total relatives sheeko 63. 8 warqad 42. 6 English: editorials Total relatives fiction 9. 2 letters 5. 1 2. 1 • Relative clauses are much more frequent in Somali than in English • But the two languages differ in the inventory of grammatical devices used for noun modification – Somali: finite relative clauses, attributive adjectives, genitives – English: finite relative clauses, attributive adjectives, genitives, • Plus: non-finite relative clauses, pre-modifying nouns, appositive noun phrases, prepositional phrases as noun modifiers

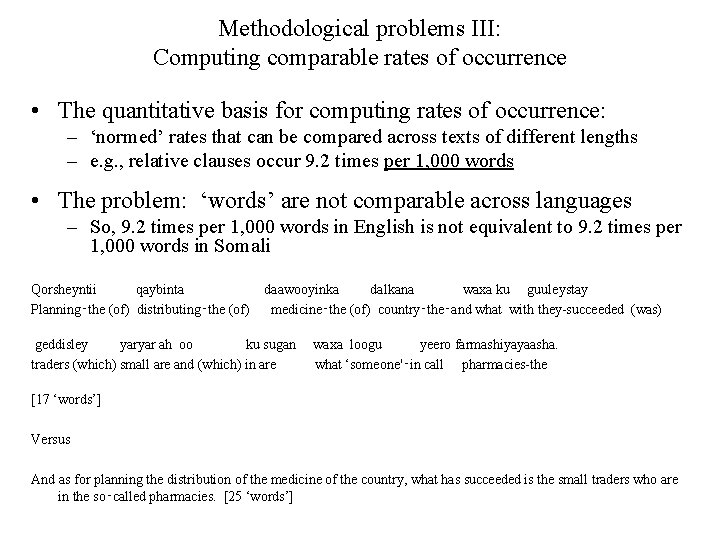

Methodological problems III: Computing comparable rates of occurrence • The quantitative basis for computing rates of occurrence: – ‘normed’ rates that can be compared across texts of different lengths – e. g. , relative clauses occur 9. 2 times per 1, 000 words • The problem: ‘words’ are not comparable across languages – So, 9. 2 times per 1, 000 words in English is not equivalent to 9. 2 times per 1, 000 words in Somali Qorsheyntii qaybinta Planning‑the (of) distributing‑the (of) daawooyinka dalkana waxa ku guuleystay medicine‑the (of) country‑the‑and what with they succeeded (was) geddisley yaryar ah oo ku sugan traders (which) small are and (which) in are waxa loogu yeero farmashiyayaasha. what ‘someone'‑in call pharmacies the [17 ‘words’] Versus And as for planning the distribution of the medicine of the country, what has succeeded is the small traders who are in the so‑called pharmacies. [25 ‘words’]

Bottom line A direct comparison of quantitative linguistic patterns of register variation across languages is difficult (!!) An alternative approach: Multi-Dimensional (MD) analysis • Comprehensive analyses of each language in its own terms (an MD analysis of each language) • Then compare the dimensions across languages – Linguistic composition of the dimensions – Functional correlates of each dimension – Register distributions along each dimension

Research goals of Multi Dimensional (MD) analysis • To identify and interpret the major parameters of linguistic variation in a language (or discourse domain) = the ‘dimensions’ • Each dimension = a set of linguistic features that tend to co occur in texts • Registers can be described and compared – For their linguistic characteristics • – For their functional associations • – the interpretation of each dimension For their quantitative similarities and differences • • determined by the linguistic composition of each dimension with respect to the full set of dimensions Each language and discourse domain is analyzed on its own terms – Based on the set of lexico grammatical features that occur in the language – Based on the set of registers found in the language/culture/domain

Steps in Multi Dimensional (MD) analysis 1. Compilation of the corpus, to ‘represent’ the range of registers in a language or specific discourse domain 2. Survey previous research studies to identify the set of relevant linguistic features 3. Grammatically annotate texts through automatic tagging 4. Establish adequate levels of reliability; interactive tag editing if required 5. Count frequencies and compute normed rates of occurrence for linguistic features 6. Factor analysis, to identify underlying co occurrence patterns among linguistic features 7. Interpretation of the factors as ‘dimensions’ 8. Analysis of the multi dimensional patterns of register variation

Back to the beginning… General spoken and written registers in English (Biber 1988; cf. 1983, 1984)

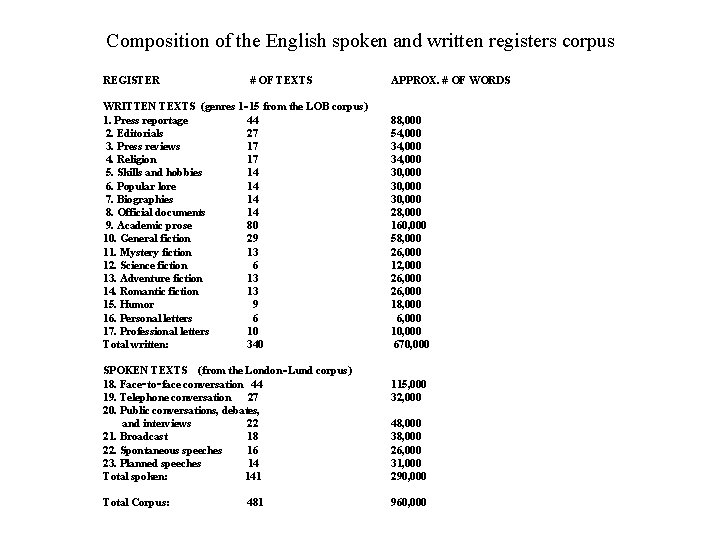

Composition of the English spoken and written registers corpus REGISTER # OF TEXTS WRITTEN TEXTS (genres 1‑ 15 from the LOB corpus) 1. Press reportage 44 2. Editorials 27 3. Press reviews 17 4. Religion 17 5. Skills and hobbies 14 6. Popular lore 14 7. Biographies 14 8. Official documents 14 9. Academic prose 80 10. General fiction 29 11. Mystery fiction 13 12. Science fiction 6 13. Adventure fiction 13 14. Romantic fiction 13 15. Humor 9 16. Personal letters 6 17. Professional letters 10 Total written: 340 SPOKEN TEXTS (from the London‑Lund corpus) 18. Face‑to‑face conversation 44 19. Telephone conversation 27 20. Public conversations, debates, and interviews 22 21. Broadcast 18 22. Spontaneous speeches 16 23. Planned speeches 14 Total spoken: 141 Total Corpus: 481 APPROX. # OF WORDS 88, 000 54, 000 34, 000 30, 000 28, 000 160, 000 58, 000 26, 000 12, 000 26, 000 18, 000 6, 000 10, 000 670, 000 115, 000 32, 000 48, 000 38, 000 26, 000 31, 000 290, 000 960, 000

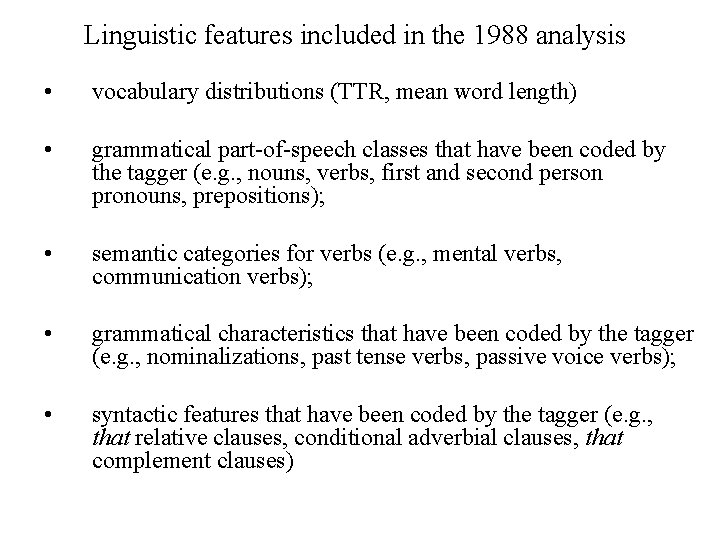

Linguistic features included in the 1988 analysis • vocabulary distributions (TTR, mean word length) • grammatical part of speech classes that have been coded by the tagger (e. g. , nouns, verbs, first and second person pronouns, prepositions); • semantic categories for verbs (e. g. , mental verbs, communication verbs); • grammatical characteristics that have been coded by the tagger (e. g. , nominalizations, past tense verbs, passive voice verbs); • syntactic features that have been coded by the tagger (e. g. , that relative clauses, conditional adverbial clauses, that complement clauses)

Counting the features • Calculate the normalized rate of occurrence for each linguistic feature in each text – Note: Each text is an observation in the research design • Allows descriptive comparisons of registers, with respect to mean scores and standard deviations

Factor analysis to identify the ‘dimensions’ Each ‘dimension’ is a group of linguistic features that tend to co occur in texts – The co occurrence patterns are identified statistically using factor analysis – Each dimension is composed of a different set of co occurring linguistic features – Dimensions are interpreted to try to capture the functions shared by the co occurring features – Because dimensions have a functional basis, there is a distinctive pattern of register variation associated with each dimension

Overview of the 1988 factor analysis 67 linguistic features used in the analysis Five major factors; Promax rotation 1) 2) 3) 4) 5) ‘Involved vs Informational Production’ ‘Narrative Discourse’ ‘Situation dependent vs Elaborated Reference’ ‘Overt Expression of Argumentation’ ‘Abstract Style’

Dimension 1 Oral versus literate discourse: ‘Involved vs Informational Production’

![Dimension 1: Involved vs informational production [‘oral’ versus ‘literate’] Positive features: Verbs: present tense Dimension 1: Involved vs informational production [‘oral’ versus ‘literate’] Positive features: Verbs: present tense](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9b0e32c1220df9fd5b0116598d4de8ba/image-21.jpg)

Dimension 1: Involved vs informational production [‘oral’ versus ‘literate’] Positive features: Verbs: present tense verbs, mental verbs, do as pro‑verb, be as main verb, possibility modals Pronouns: 1 st person pronouns, 2 nd person pronouns, it, demonstrative pronouns, indefinite pronouns Adverbs: general emphatics, hedges, amplifiers Dependent clauses: that complement clauses (with that deletion), causative adverbial clauses, WH clauses Other: contractions, analytic negation, discourse particles, sentence relatives, WH questions, clause coordination ================= Negative features: Nouns, long words, prepositional phrases, attributive adjectives, lexical diversity

Compute ‘dimension scores’ for each text Dimension 1 Score = (present tense verbs + mental verbs + 1 st person pronouns + 2 nd person pronouns + emphatics + hedges + that complement clauses + causative adverbial clauses + WH clauses + contractions + etc…) (nouns + long words + prepositional phrases + attributive adjectives + type/token ratio) • Linguistic counts are converted to ‘standardized scores’ before computing dimension scores – Mean for the feature in the entire corpus = 0 – Standard deviation = 1 • Dimension scores are computed for each text • It is then possible to compute mean dimension scores for each register, and to compare registers quantitatively with respect to the linguistic composition of the dimension

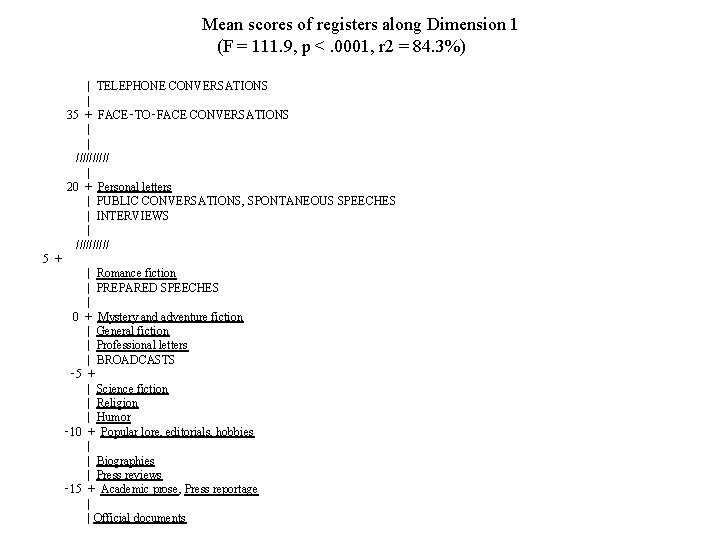

Mean scores of registers along Dimension 1 (F = 111. 9, p <. 0001, r 2 = 84. 3%) | TELEPHONE CONVERSATIONS | 35 + FACE‑TO‑FACE CONVERSATIONS | | ///// | 20 + Personal letters | PUBLIC CONVERSATIONS, SPONTANEOUS SPEECHES | INTERVIEWS | ///// 5 + | Romance fiction | PREPARED SPEECHES | 0 + Mystery and adventure fiction | General fiction | Professional letters | BROADCASTS ‑ 5 + | Science fiction | Religion | Humor ‑ 10 + Popular lore, editorials, hobbies | | Biographies | Press reviews ‑ 15 + Academic prose, Press reportage | | Official documents

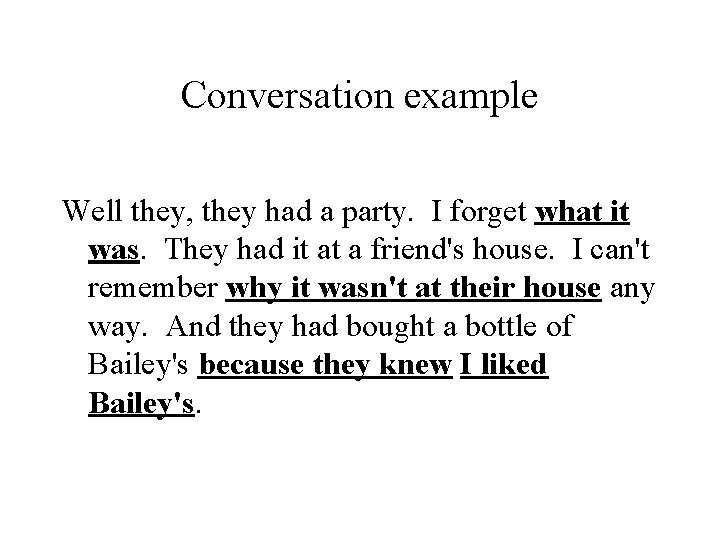

Conversation example Well they, they had a party. I forget what it was. They had it at a friend's house. I can't remember why it wasn't at their house any way. And they had bought a bottle of Bailey's because they knew I liked Bailey's.

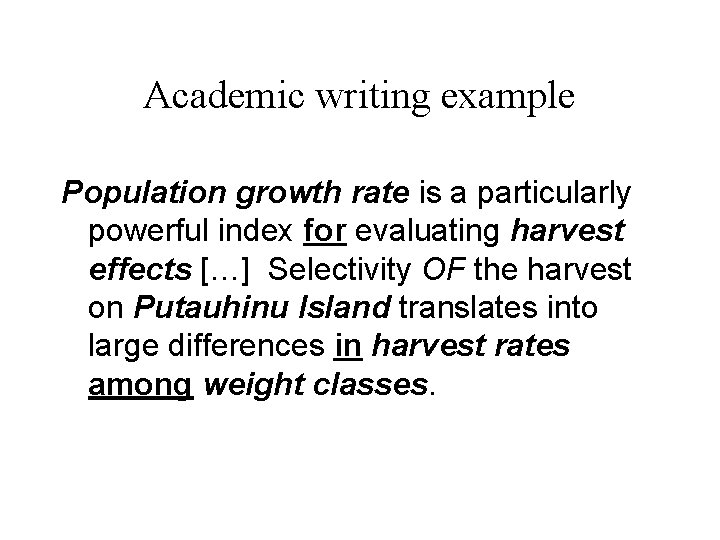

Academic writing example Population growth rate is a particularly powerful index for evaluating harvest effects […] Selectivity OF the harvest on Putauhinu Island translates into large differences in harvest rates among weight classes.

Another dimension from the 1988 analysis: Dimension 2: Narrative Discourse

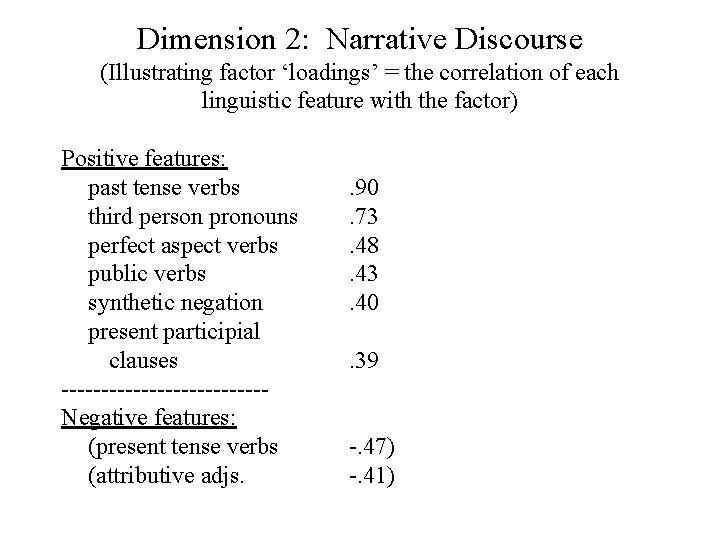

Dimension 2: Narrative Discourse (Illustrating factor ‘loadings’ = the correlation of each linguistic feature with the factor) Positive features: past tense verbs third person pronouns perfect aspect verbs public verbs synthetic negation present participial clauses Negative features: (present tense verbs (attributive adjs. . 90. 73. 48. 43. 40. 39 . 47) . 41)

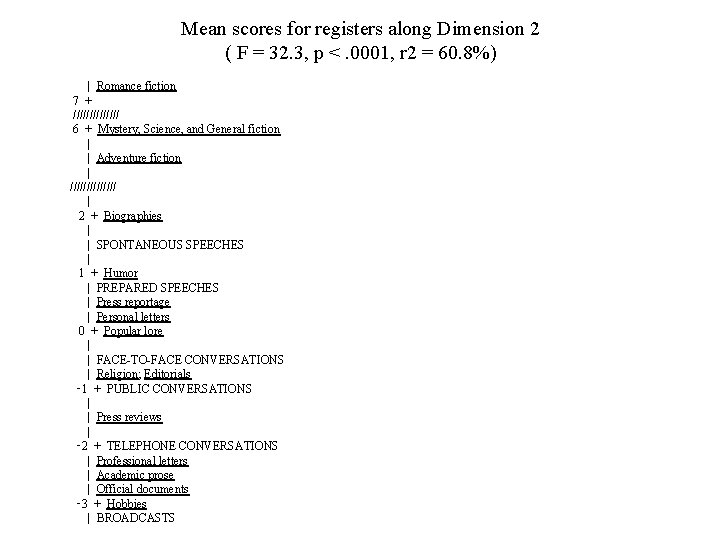

Mean scores for registers along Dimension 2 ( F = 32. 3, p <. 0001, r 2 = 60. 8%) | Romance fiction 7 + /////// 6 + Mystery, Science, and General fiction | | Adventure fiction | /////// | 2 + Biographies | | SPONTANEOUS SPEECHES | 1 + Humor | PREPARED SPEECHES | Press reportage | Personal letters 0 + Popular lore | | FACE TO FACE CONVERSATIONS | Religion; Editorials ‑ 1 + PUBLIC CONVERSATIONS | | Press reviews | ‑ 2 + TELEPHONE CONVERSATIONS | Professional letters | Academic prose | Official documents ‑ 3 + Hobbies | BROADCASTS

![Functional interpretation [Summarized in the dimension titles] Based on: • The shared functional associations Functional interpretation [Summarized in the dimension titles] Based on: • The shared functional associations](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9b0e32c1220df9fd5b0116598d4de8ba/image-29.jpg)

Functional interpretation [Summarized in the dimension titles] Based on: • The shared functional associations of the co occurring linguistic features grouped on the dimension • The communicative/situational associations of the similarities/differences among registers along the dimension • Detailed consideration of these co occurring linguistic features in particular texts from those registers

Subsequent applications of MD analysis • To carry out an analysis of register variation within more restricted discourse domains • To carry out ‘comprehensive’ linguistic comparisons of spoken and written registers in other languages – Modeled after the 1988 study of English

Generalizable findings across MD studies 1) Possible ‘universal’ dimensions of register variation – – – Narrative versus Non narrative Discourse Oral versus Literate Discourse Found across languages and across different discourse domains 2) ‘Unique’ dimensions in each language/domain – Reflect the distinctive linguistic resources of the language and the distinctive set of registers found in the language

![‘Universal’ dimensions [I]: Narrative versus Non-narrative ‘Universal’ dimensions [I]: Narrative versus Non-narrative](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9b0e32c1220df9fd5b0116598d4de8ba/image-32.jpg)

‘Universal’ dimensions [I]: Narrative versus Non-narrative

![‘Universal’ dimensions [I]: Narrative versus Non-narrative • Linguistic correlates – – Past/preterit/imperfect/perfect tense Communication ‘Universal’ dimensions [I]: Narrative versus Non-narrative • Linguistic correlates – – Past/preterit/imperfect/perfect tense Communication](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9b0e32c1220df9fd5b0116598d4de8ba/image-33.jpg)

‘Universal’ dimensions [I]: Narrative versus Non-narrative • Linguistic correlates – – Past/preterit/imperfect/perfect tense Communication verbs, activity verbs 3 rd person pronouns Time adverbials • Register distribution – Novels, short stories, folktales, personal narratives, (informational reportage) versus – Other spoken and written registers • Not so surprising, given that ‘narration’ has long been regarded as a basic mode of discourse – But more surprising that the other ‘modes’ (description, exposition, argumentation) are not represented as dimensions

Narrative versus Non narrative across discourse domains in English

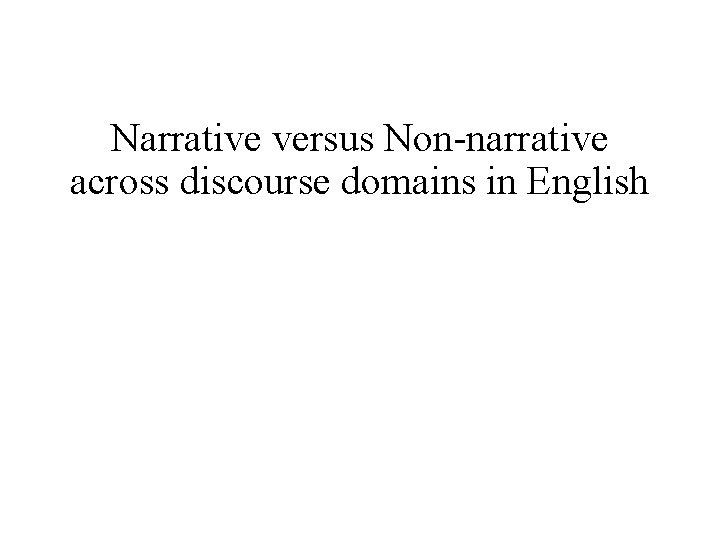

Discourse domain Linguistic features defining the dimension General spoken and written past tense, perfect registers; Biber (1883, aspect, 3 rd person 1988) pronouns, communication verbs VERSUS present tense, attributive adjectives University spoken and 3 rd person pronouns, written registers; human nouns, Biber (2006) communication verbs, mental verbs, past tense, stance verb + that clause, stance noun + that clause Register pattern along the dimension fiction VERSUS informational writing, broadcasts, telephone conversations Elementary school spoken and written registers; Reppen (2001) fiction, social studies textbooks VERSUS science textbooks, spoken monologues past tense, perfect aspect communication verbs, diversified vocabulary VERSUS present tense, infinitives office hours, study groups VERSUS textbooks, course packs, institutional writing

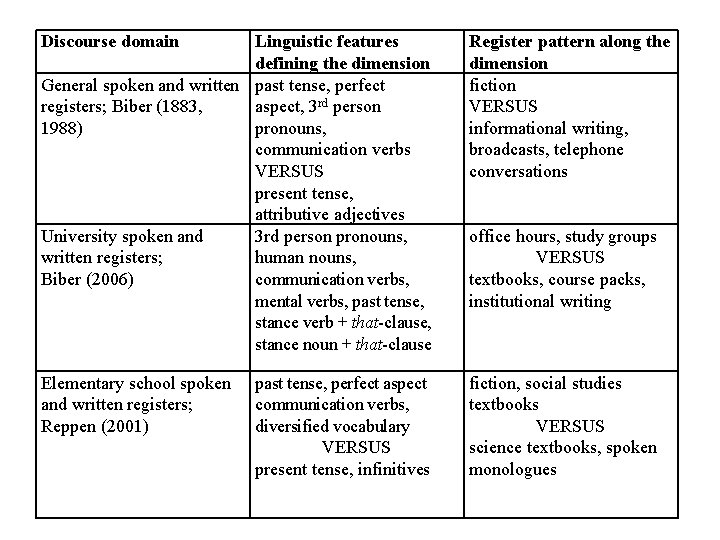

Discourse domain Linguistic features defining the Register pattern along the dimension ESL spoken and written exam responses; Biber and Gray (2012) past tense, 1 st person pronouns VERSUS present tense Conversational text types; Biber (2008) past tense, 3 rd person pronouns, communication verb + that clause VERSUS present tense spoken, independent tasks VERSUS integrated tasks

Discourse domain 19 th c. fictional novels; Egbert (2012) Linguistic features defining the dimension past tense verbs, simple occurrence verbs, 3 rd person pronouns VERSUS present tense verbs, have as main verb, 1 st and 2 nd person pronouns, modals, WH questions Register pattern along the dimension Hawthorne, Melville VERSUS Alcott, Twain, James Academic research articles across disciplines; Gray (2011) past tense verbs, aspectual verbs, perfect aspect qualitative history / political science / applied verbs, communication verbs, present progressive linguistics verbs, 3 rd person pronouns, group nouns, nominalizations, animate nouns, time attributive adjectives, coordinating conjunctions, that relative clauses, that clauses controlled by non factive verbs, to clauses controlled by verbs of desire, modality, causation and effort, long words VERSUS technical nouns, quantity nouns, concrete nouns, VERSUS attributive adjectives indicating size, passive theoretical / quantitative physics voice verbs Moves in biochemistry research articles; Kanoksilapatham (2007) (cf. Biber and Jones 2007) past tense, passives methodological moves: VERSUS describing procedures and definite articles, nominalizations, materials prepositions VERSUS all other moves from introduction, results, and discussion

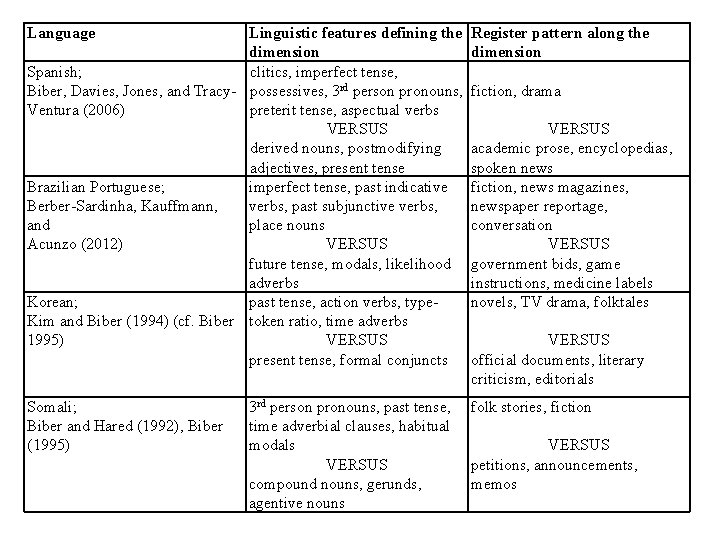

Narrative versus Non narrative across languages

Language Linguistic features defining the dimension Spanish; clitics, imperfect tense, Biber, Davies, Jones, and Tracy possessives, 3 rd person pronouns, Ventura (2006) preterit tense, aspectual verbs VERSUS derived nouns, postmodifying adjectives, present tense Brazilian Portuguese; imperfect tense, past indicative Berber Sardinha, Kauffmann, verbs, past subjunctive verbs, and place nouns Acunzo (2012) VERSUS future tense, modals, likelihood adverbs Korean; past tense, action verbs, type Kim and Biber (1994) (cf. Biber token ratio, time adverbs 1995) VERSUS present tense, formal conjuncts Register pattern along the dimension Somali; Biber and Hared (1992), Biber (1995) folk stories, fiction 3 rd person pronouns, past tense, time adverbial clauses, habitual modals VERSUS compound nouns, gerunds, agentive nouns fiction, drama VERSUS academic prose, encyclopedias, spoken news fiction, news magazines, newspaper reportage, conversation VERSUS government bids, game instructions, medicine labels novels, TV drama, folktales VERSUS official documents, literary criticism, editorials VERSUS petitions, announcements, memos

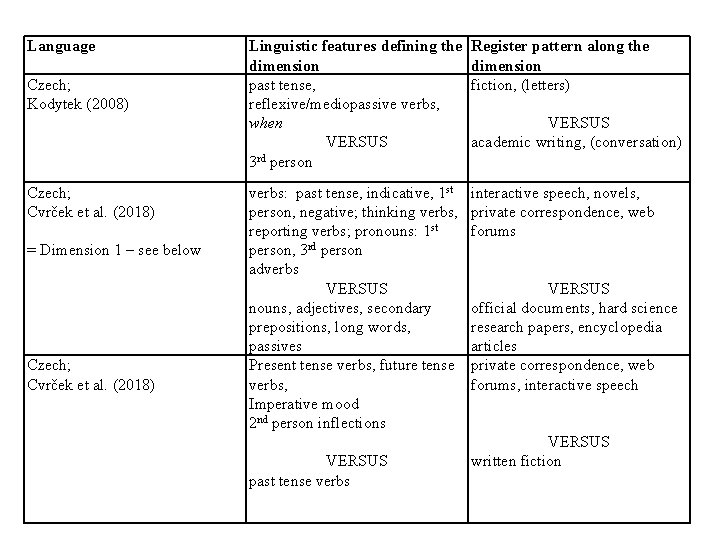

Language Czech; Kodytek (2008) Czech; Cvrček et al. (2018) = Dimension 1 – see below Czech; Cvrček et al. (2018) Linguistic features defining the dimension past tense, reflexive/mediopassive verbs, when VERSUS 3 rd person Register pattern along the dimension fiction, (letters) verbs: past tense, indicative, 1 st person, negative; thinking verbs, reporting verbs; pronouns: 1 st person, 3 rd person adverbs VERSUS nouns, adjectives, secondary prepositions, long words, passives Present tense verbs, future tense verbs, Imperative mood 2 nd person inflections interactive speech, novels, private correspondence, web forums VERSUS past tense verbs VERSUS academic writing, (conversation) VERSUS official documents, hard science research papers, encyclopedia articles private correspondence, web forums, interactive speech VERSUS written fiction

![‘Universal’ dimensions [II]: ‘Oral’ versus ‘Literate’ Discourse ‘Universal’ dimensions [II]: ‘Oral’ versus ‘Literate’ Discourse](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9b0e32c1220df9fd5b0116598d4de8ba/image-41.jpg)

‘Universal’ dimensions [II]: ‘Oral’ versus ‘Literate’ Discourse

![‘Universal’ dimensions [II]: ‘Oral’ versus ‘Literate’ Discourse • Linguistic correlates – verbs and clauses, ‘Universal’ dimensions [II]: ‘Oral’ versus ‘Literate’ Discourse • Linguistic correlates – verbs and clauses,](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9b0e32c1220df9fd5b0116598d4de8ba/image-42.jpg)

‘Universal’ dimensions [II]: ‘Oral’ versus ‘Literate’ Discourse • Linguistic correlates – verbs and clauses, pronouns, adverbs, finite complement clauses, finite adverbial clauses, stance devices versus – nouns, adjectives, prepositional phrases, diverse vocabulary • Functional associations – Interaction, personal involvement, discussion/evaluation versus informational focus – Real time production versus planned/revised/edited discourse – Elaborated versus compressed styles • Register distribution – Often speech (and popular writing) versus informational writing – But…

![‘Universal’ dimensions [II]: ‘Oral’ versus ‘Literate’ Discourse • The most surprising finding to emerge ‘Universal’ dimensions [II]: ‘Oral’ versus ‘Literate’ Discourse • The most surprising finding to emerge](http://slidetodoc.com/presentation_image_h2/9b0e32c1220df9fd5b0116598d4de8ba/image-43.jpg)

‘Universal’ dimensions [II]: ‘Oral’ versus ‘Literate’ Discourse • The most surprising finding to emerge from MD studies • Found regardless of mode, discourse domain, language • Almost always the first dimension • Accounts for the greatest amount of shared linguistic variation in the text sample • The linguistic composition (clausal versus phrasal) and functional associations of this dimension are remarkably stable across discourse domains and languages • BUT the particular registers that are distinguished vary according to the language/culture/discourse domain

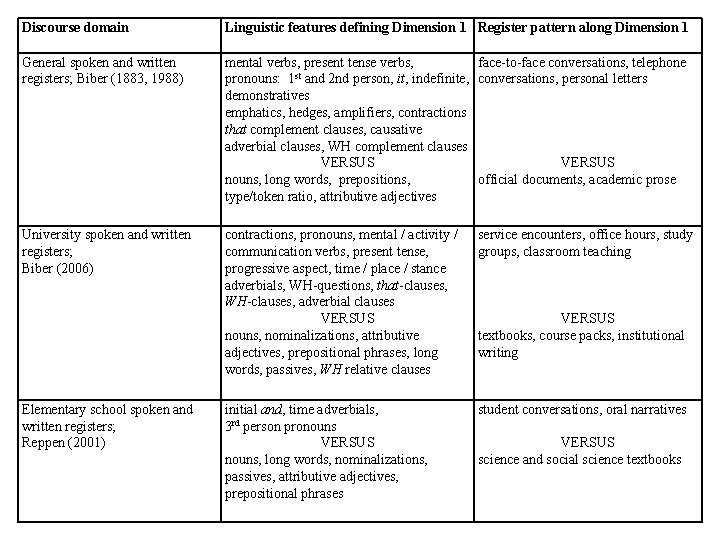

The ‘Oral versus Literate’ dimension across discourse domains in English

Discourse domain Linguistic features defining Dimension 1 Register pattern along Dimension 1 General spoken and written registers; Biber (1883, 1988) mental verbs, present tense verbs, face to face conversations, telephone st pronouns: 1 and 2 nd person, it, indefinite, conversations, personal letters demonstratives emphatics, hedges, amplifiers, contractions that complement clauses, causative adverbial clauses, WH complement clauses VERSUS nouns, long words, prepositions, official documents, academic prose type/token ratio, attributive adjectives University spoken and written registers; Biber (2006) contractions, pronouns, mental / activity / communication verbs, present tense, progressive aspect, time / place / stance adverbials, WH questions, that clauses, WH clauses, adverbial clauses VERSUS nouns, nominalizations, attributive adjectives, prepositional phrases, long words, passives, WH relative clauses service encounters, office hours, study groups, classroom teaching initial and, time adverbials, 3 rd person pronouns VERSUS nouns, long words, nominalizations, passives, attributive adjectives, prepositional phrases student conversations, oral narratives Elementary school spoken and written registers; Reppen (2001) VERSUS textbooks, course packs, institutional writing VERSUS science and social science textbooks

Discourse domain Linguistic features defining Dimension 1 Register pattern along Dimension 1 ESL spoken and written exam responses; Biber and Gray (2012) mental verbs, present tense, modals, 3 rd person pronouns, that clauses, adverbial clauses VERSUS nouns, attributive adjectives, prepositional phrases, long words, passives spoken, independent tasks (low scoring) VERSUS written, integrated tasks (high scoring)

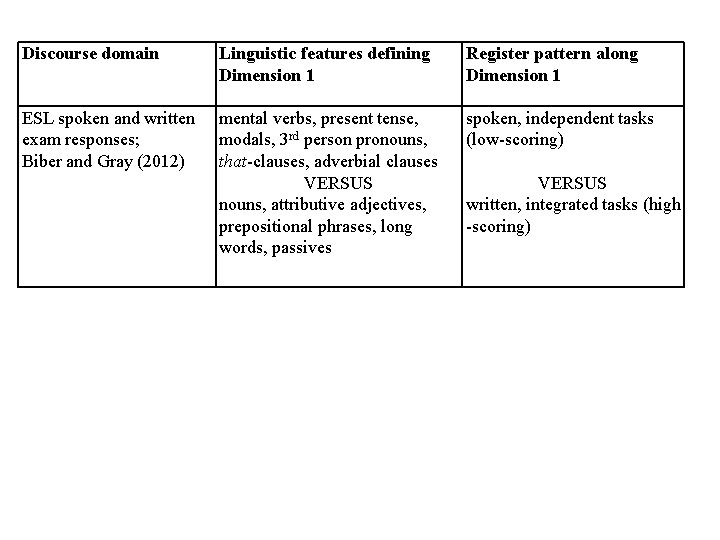

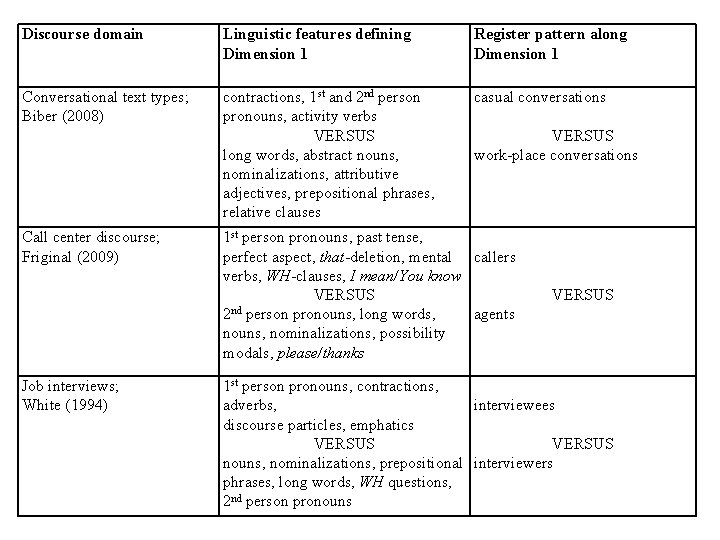

The ‘Oral versus Literate’ dimension in spoken discourse domains

Discourse domain Linguistic features defining Dimension 1 Register pattern along Dimension 1 Conversational text types; Biber (2008) contractions, 1 st and 2 nd person pronouns, activity verbs VERSUS long words, abstract nouns, nominalizations, attributive adjectives, prepositional phrases, relative clauses casual conversations Call center discourse; Friginal (2009) Job interviews; White (1994) VERSUS work place conversations 1 st person pronouns, past tense, perfect aspect, that deletion, mental callers verbs, WH clauses, I mean/You know VERSUS nd 2 person pronouns, long words, agents nouns, nominalizations, possibility modals, please/thanks VERSUS 1 st person pronouns, contractions, adverbs, interviewees discourse particles, emphatics VERSUS nouns, nominalizations, prepositional interviewers phrases, long words, WH questions, 2 nd person pronouns

The ‘Oral versus Literate’ dimension in written discourse domains

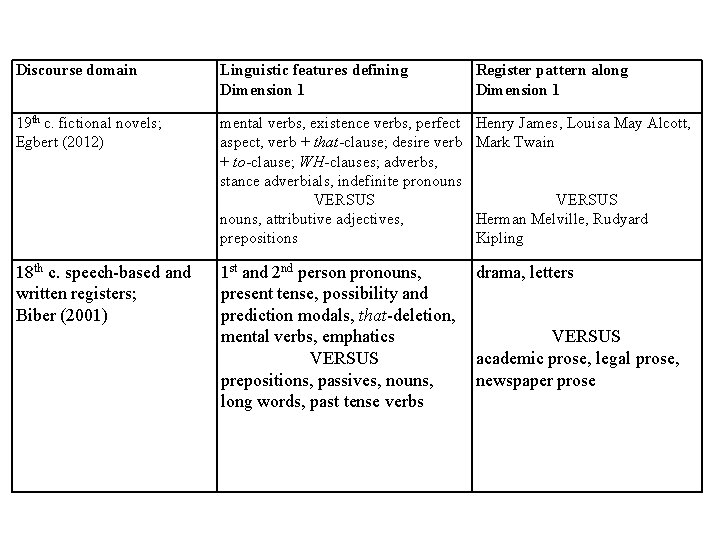

Discourse domain Linguistic features defining Dimension 1 Register pattern along Dimension 1 19 th c. fictional novels; Egbert (2012) mental verbs, existence verbs, perfect aspect, verb + that clause; desire verb + to clause; WH clauses; adverbs, stance adverbials, indefinite pronouns VERSUS nouns, attributive adjectives, prepositions Henry James, Louisa May Alcott, Mark Twain 1 st and 2 nd person pronouns, present tense, possibility and prediction modals, that deletion, mental verbs, emphatics VERSUS prepositions, passives, nouns, long words, past tense verbs drama, letters 18 th c. speech based and written registers; Biber (2001) VERSUS Herman Melville, Rudyard Kipling VERSUS academic prose, legal prose, newspaper prose

Discourse domain Linguistic features defining Dimension 1 Moves in biochemistry research articles; Kanoksilapatham (2007) (cf. Biber and Jones 2007) 0 methodological moves describing VERSUS procedures and materials long words, nouns, attributive VERSUS adjectives, numerals, technical jargon moves introducing the topic and the study Written legal registers; Goźdź pronouns: 3 rd person, demonstrative, Roszkowski (2011) indefinite; past tense, perfect aspect mental verbs; stance adverbs, downtoners; causative adverbial clauses, that relative clauses that complement clauses (controlled by verbs, adjectives, and nouns) VERSUS prepositions, phrasal coordination, nominalizations, quantity nouns, shall, passives Register pattern along Dimension 1 textbooks, academic articles, legal briefs VERSUS contracts, legislation

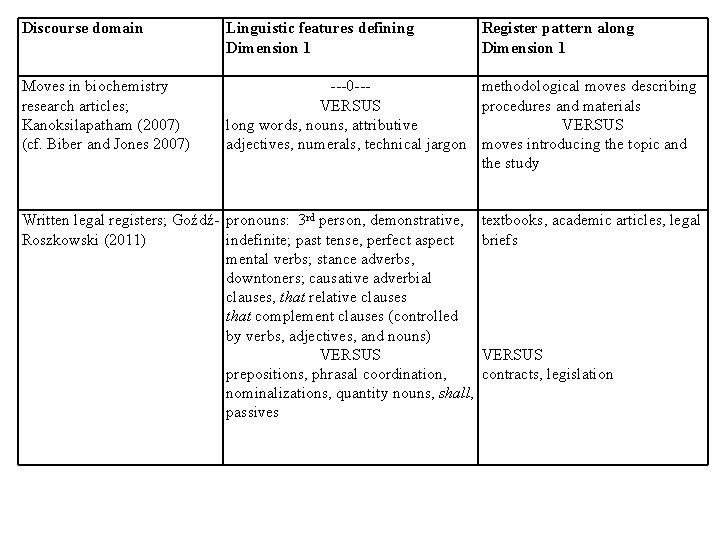

Discourse domain Linguistic features defining Dimension 1 Register pattern along Dimension 1 Academic research articles across disciplines; Gray (2011) pronoun it, 1 st person pronouns , demonstrative pronouns, be as main verb, have as main verb, causative verbs, modals of prediction, possibility, necessity; general adverbs, stance adverbials, adverbials of time; nouns of cognition, predicative adjectives, evaluative attributive adjectives; conditional adverbial clauses, that clauses controlled by nouns of likelihood, that clauses controlled by verbs of likelihood, that clauses controlled by factive adjectives, that clauses controlled by attitudinal nouns, that clauses controlled by factive nouns, wh clauses; to clauses controlled by stance adjectives, to clauses controlled by verbs of probability VERSUS nouns, process nouns, past tense verbs, prepositions, type token ratio, word length; passive postnominal clauses, agentless passive voice verbs past tense verbs, aspectual verbs, perfect aspect verbs, communication verbs, present progressive verbs, 3 rd person pronouns, group nouns, nominalizations, animate nouns, time attributive adjectives, coordinating conjunctions, that relative clauses, that clauses controlled by non factive verbs, to clauses controlled by verbs of desire, modality, causation and effort, long words VERSUS technical nouns, quantity nouns, concrete nouns, attributive adjectives indicating size, passive voice verbs theoretical philosophy Cf. Academic research articles across disciplines; Gray (2011) [oral/literate + narrative] VERSUS quantitative biology, quantitative physics qualitative history / political science / applied linguistics VERSUS theoretical / quantitative physics

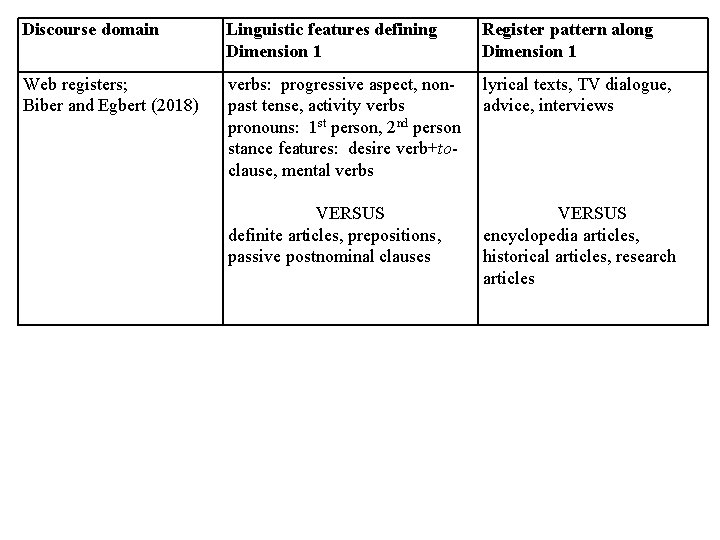

Discourse domain Linguistic features defining Dimension 1 Register pattern along Dimension 1 Web registers; Biber and Egbert (2018) verbs: progressive aspect, non past tense, activity verbs pronouns: 1 st person, 2 nd person stance features: desire verb+to clause, mental verbs lyrical texts, TV dialogue, advice, interviews VERSUS definite articles, prepositions, passive postnominal clauses VERSUS encyclopedia articles, historical articles, research articles

The ‘Oral versus Literate’ dimension across languages

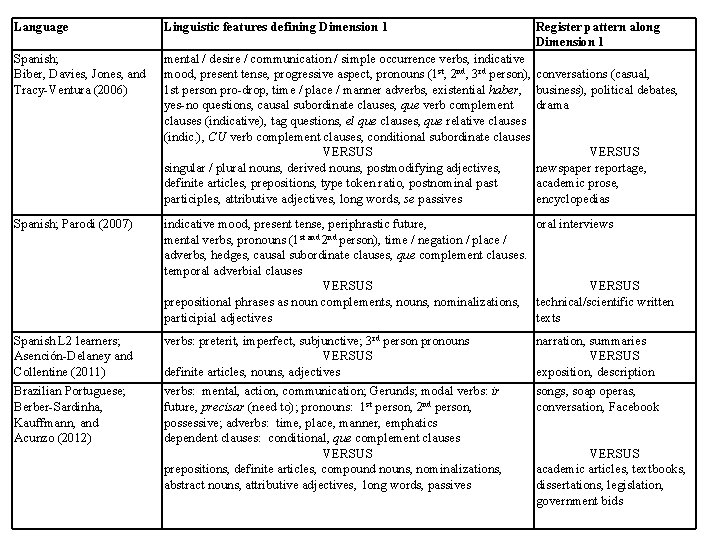

Language Linguistic features defining Dimension 1 Spanish; Biber, Davies, Jones, and Tracy Ventura (2006) mental / desire / communication / simple occurrence verbs, indicative mood, present tense, progressive aspect, pronouns (1 st, 2 nd, 3 rd person), 1 st person pro drop, time / place / manner adverbs, existential haber, yes no questions, causal subordinate clauses, que verb complement clauses (indicative), tag questions, el que clauses, que relative clauses (indic. ), CU verb complement clauses, conditional subordinate clauses VERSUS singular / plural nouns, derived nouns, postmodifying adjectives, definite articles, prepositions, type token ratio, postnominal past participles, attributive adjectives, long words, se passives Register pattern along Dimension 1 conversations (casual, business), political debates, drama VERSUS newspaper reportage, academic prose, encyclopedias Spanish; Parodi (2007) indicative mood, present tense, periphrastic future, oral interviews mental verbs, pronouns (1 st and 2 nd person), time / negation / place / adverbs, hedges, causal subordinate clauses, que complement clauses. temporal adverbial clauses VERSUS prepositional phrases as noun complements, nouns, nominalizations, technical/scientific written participial adjectives texts Spanish L 2 learners; Asención Delaney and Collentine (2011) Brazilian Portuguese; Berber Sardinha, Kauffmann, and Acunzo (2012) verbs: preterit, imperfect, subjunctive; 3 rd person pronouns VERSUS definite articles, nouns, adjectives verbs: mental, action, communication; Gerunds; modal verbs: ir future, precisar (need to); pronouns: 1 st person, 2 nd person, possessive; adverbs: time, place, manner, emphatics dependent clauses: conditional, que complement clauses VERSUS prepositions, definite articles, compound nouns, nominalizations, abstract nouns, attributive adjectives, long words, passives narration, summaries VERSUS exposition, description songs, soap operas, conversation, Facebook VERSUS academic articles, textbooks, dissertations, legislation, government bids

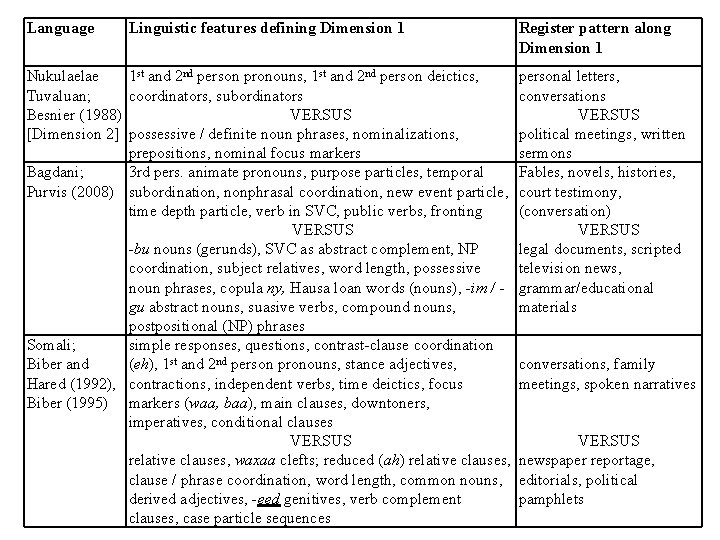

Language Linguistic features defining Dimension 1 Nukulaelae 1 st and 2 nd person pronouns, 1 st and 2 nd person deictics, Tuvaluan; coordinators, subordinators Besnier (1988) VERSUS [Dimension 2] possessive / definite noun phrases, nominalizations, prepositions, nominal focus markers Bagdani; 3 rd pers. animate pronouns, purpose particles, temporal Purvis (2008) subordination, nonphrasal coordination, new event particle, time depth particle, verb in SVC, public verbs, fronting VERSUS -bu nouns (gerunds), SVC as abstract complement, NP coordination, subject relatives, word length, possessive noun phrases, copula ny, Hausa loan words (nouns), -im / gu abstract nouns, suasive verbs, compound nouns, postpositional (NP) phrases Somali; simple responses, questions, contrast clause coordination Biber and (eh), 1 st and 2 nd person pronouns, stance adjectives, Hared (1992), contractions, independent verbs, time deictics, focus Biber (1995) markers (waa, baa), main clauses, downtoners, imperatives, conditional clauses VERSUS relative clauses, waxaa clefts; reduced (ah) relative clauses, clause / phrase coordination, word length, common nouns, derived adjectives, -eed genitives, verb complement clauses, case particle sequences Register pattern along Dimension 1 personal letters, conversations VERSUS political meetings, written sermons Fables, novels, histories, court testimony, (conversation) VERSUS legal documents, scripted television news, grammar/educational materials conversations, family meetings, spoken narratives VERSUS newspaper reportage, editorials, political pamphlets

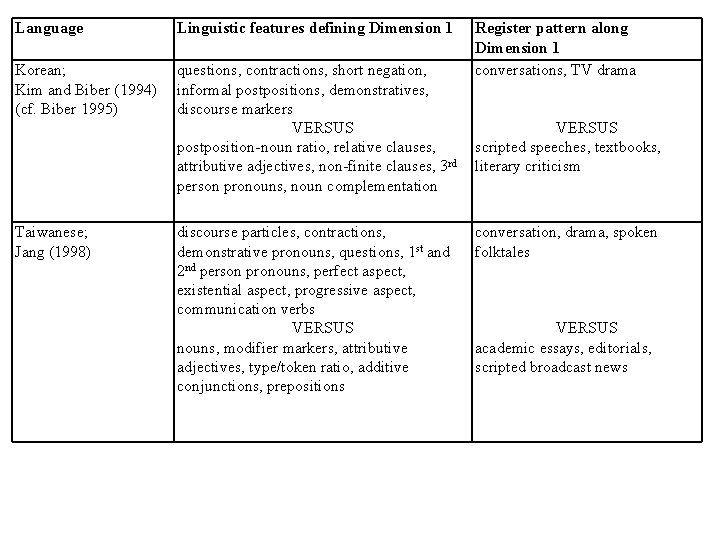

Language Linguistic features defining Dimension 1 Korean; Kim and Biber (1994) (cf. Biber 1995) questions, contractions, short negation, informal postpositions, demonstratives, discourse markers VERSUS postposition noun ratio, relative clauses, attributive adjectives, non finite clauses, 3 rd person pronouns, noun complementation Taiwanese; Jang (1998) discourse particles, contractions, demonstrative pronouns, questions, 1 st and 2 nd person pronouns, perfect aspect, existential aspect, progressive aspect, communication verbs VERSUS nouns, modifier markers, attributive adjectives, type/token ratio, additive conjunctions, prepositions Register pattern along Dimension 1 conversations, TV drama VERSUS scripted speeches, textbooks, literary criticism conversation, drama, spoken folktales VERSUS academic essays, editorials, scripted broadcast news

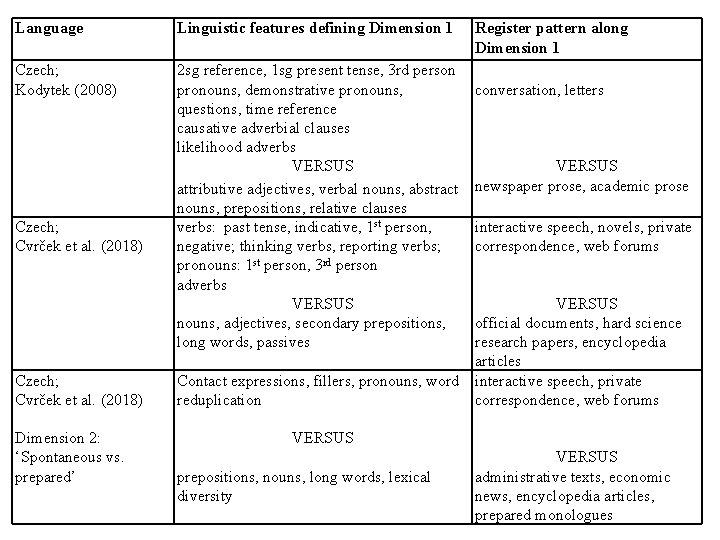

Language Linguistic features defining Dimension 1 Czech; Kodytek (2008) 2 sg reference, 1 sg present tense, 3 rd person pronouns, demonstrative pronouns, questions, time reference causative adverbial clauses likelihood adverbs VERSUS attributive adjectives, verbal nouns, abstract nouns, prepositions, relative clauses verbs: past tense, indicative, 1 st person, negative; thinking verbs, reporting verbs; pronouns: 1 st person, 3 rd person adverbs VERSUS nouns, adjectives, secondary prepositions, long words, passives Czech; Cvrček et al. (2018) Dimension 2: ‘Spontaneous vs. prepared’ Register pattern along Dimension 1 conversation, letters VERSUS newspaper prose, academic prose interactive speech, novels, private correspondence, web forums VERSUS official documents, hard science research papers, encyclopedia articles Contact expressions, fillers, pronouns, word interactive speech, private reduplication correspondence, web forums VERSUS prepositions, nouns, long words, lexical diversity VERSUS administrative texts, economic news, encyclopedia articles, prepared monologues

‘Unique’ dimensions

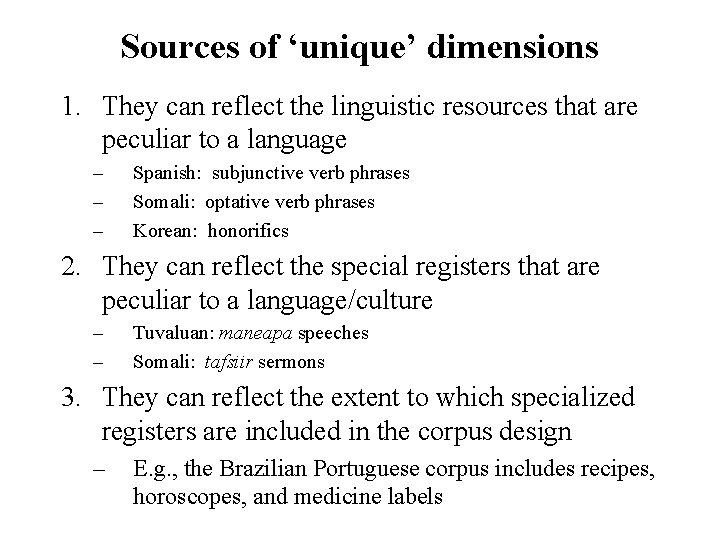

Sources of ‘unique’ dimensions 1. They can reflect the linguistic resources that are peculiar to a language – – – Spanish: subjunctive verb phrases Somali: optative verb phrases Korean: honorifics 2. They can reflect the special registers that are peculiar to a language/culture – – Tuvaluan: maneapa speeches Somali: tafsiir sermons 3. They can reflect the extent to which specialized registers are included in the corpus design – E. g. , the Brazilian Portuguese corpus includes recipes, horoscopes, and medicine labels

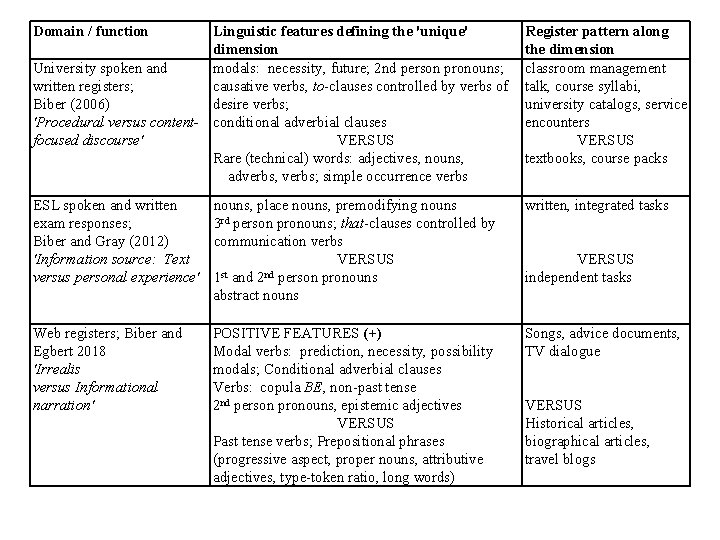

‘Unique’ dimensions in English discourse domains

Domain / function Linguistic features defining the 'unique' dimension University spoken and modals: necessity, future; 2 nd person pronouns; written registers; causative verbs, to clauses controlled by verbs of Biber (2006) desire verbs; 'Procedural versus content- conditional adverbial clauses focused discourse' VERSUS Rare (technical) words: adjectives, nouns, adverbs, verbs; simple occurrence verbs Register pattern along the dimension classroom management talk, course syllabi, university catalogs, service encounters VERSUS textbooks, course packs ESL spoken and written exam responses; Biber and Gray (2012) 'Information source: Text versus personal experience' nouns, place nouns, premodifying nouns 3 rd person pronouns; that clauses controlled by communication verbs VERSUS st nd 1 and 2 person pronouns abstract nouns written, integrated tasks Web registers; Biber and Egbert 2018 'Irrealis versus Informational narration' POSITIVE FEATURES (+) Modal verbs: prediction, necessity, possibility modals; Conditional adverbial clauses Verbs: copula BE, non past tense 2 nd person pronouns, epistemic adjectives VERSUS Past tense verbs; Prepositional phrases (progressive aspect, proper nouns, attributive adjectives, type token ratio, long words) Songs, advice documents, TV dialogue VERSUS independent tasks VERSUS Historical articles, biographical articles, travel blogs

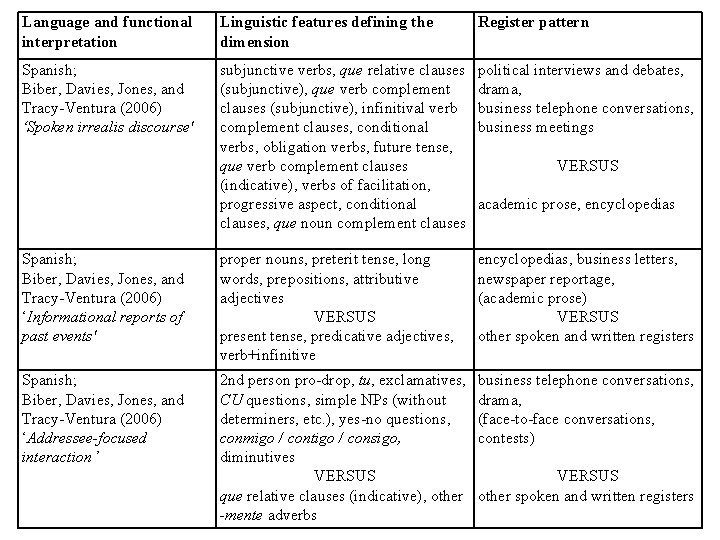

‘Unique’ dimensions across languages

Language and functional interpretation Linguistic features defining the dimension Register pattern Spanish; Biber, Davies, Jones, and Tracy Ventura (2006) ‘Spoken irrealis discourse' subjunctive verbs, que relative clauses (subjunctive), que verb complement clauses (subjunctive), infinitival verb complement clauses, conditional verbs, obligation verbs, future tense, que verb complement clauses (indicative), verbs of facilitation, progressive aspect, conditional clauses, que noun complement clauses political interviews and debates, drama, business telephone conversations, business meetings Spanish; Biber, Davies, Jones, and Tracy Ventura (2006) ‘Informational reports of past events' proper nouns, preterit tense, long words, prepositions, attributive adjectives VERSUS present tense, predicative adjectives, verb+infinitive encyclopedias, business letters, newspaper reportage, (academic prose) VERSUS other spoken and written registers Spanish; Biber, Davies, Jones, and Tracy Ventura (2006) ‘Addressee-focused interaction ’ 2 nd person pro drop, tu, exclamatives, CU questions, simple NPs (without determiners, etc. ), yes no questions, conmigo / contigo / consigo, diminutives VERSUS que relative clauses (indicative), other -mente adverbs business telephone conversations, drama, (face to face conversations, contests) VERSUS academic prose, encyclopedias VERSUS other spoken and written registers

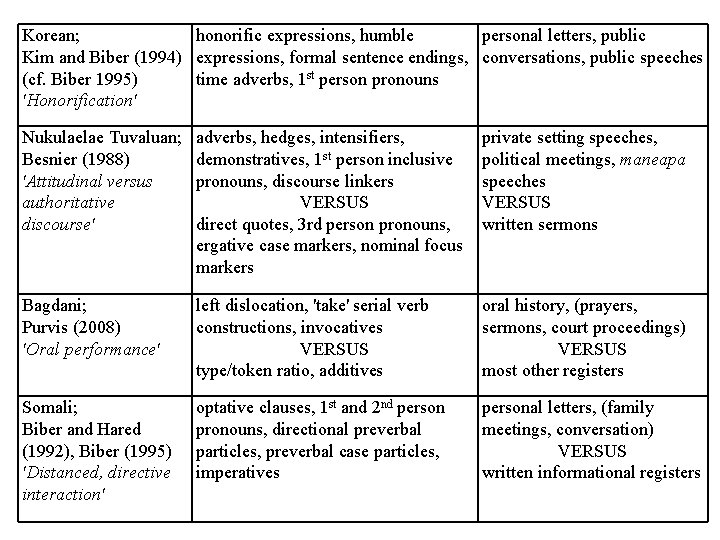

Korean; honorific expressions, humble personal letters, public Kim and Biber (1994) expressions, formal sentence endings, conversations, public speeches (cf. Biber 1995) time adverbs, 1 st person pronouns 'Honorification' Nukulaelae Tuvaluan; Besnier (1988) 'Attitudinal versus authoritative discourse' adverbs, hedges, intensifiers, demonstratives, 1 st person inclusive pronouns, discourse linkers VERSUS direct quotes, 3 rd person pronouns, ergative case markers, nominal focus markers private setting speeches, political meetings, maneapa speeches VERSUS written sermons Bagdani; Purvis (2008) 'Oral performance' left dislocation, 'take' serial verb constructions, invocatives VERSUS type/token ratio, additives oral history, (prayers, sermons, court proceedings) VERSUS most other registers Somali; Biber and Hared (1992), Biber (1995) 'Distanced, directive interaction' optative clauses, 1 st and 2 nd person pronouns, directional preverbal particles, preverbal case particles, imperatives personal letters, (family meetings, conversation) VERSUS written informational registers

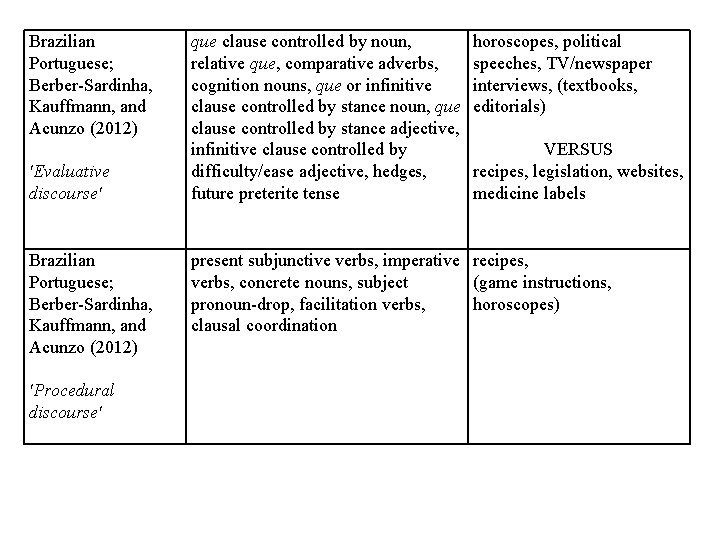

Brazilian Portuguese; Berber Sardinha, Kauffmann, and Acunzo (2012) 'Evaluative discourse' Brazilian Portuguese; Berber Sardinha, Kauffmann, and Acunzo (2012) 'Procedural discourse' que clause controlled by noun, relative que, comparative adverbs, cognition nouns, que or infinitive clause controlled by stance noun, que clause controlled by stance adjective, infinitive clause controlled by difficulty/ease adjective, hedges, future preterite tense horoscopes, political speeches, TV/newspaper interviews, (textbooks, editorials) VERSUS recipes, legislation, websites, medicine labels present subjunctive verbs, imperative recipes, verbs, concrete nouns, subject (game instructions, pronoun drop, facilitation verbs, horoscopes) clausal coordination

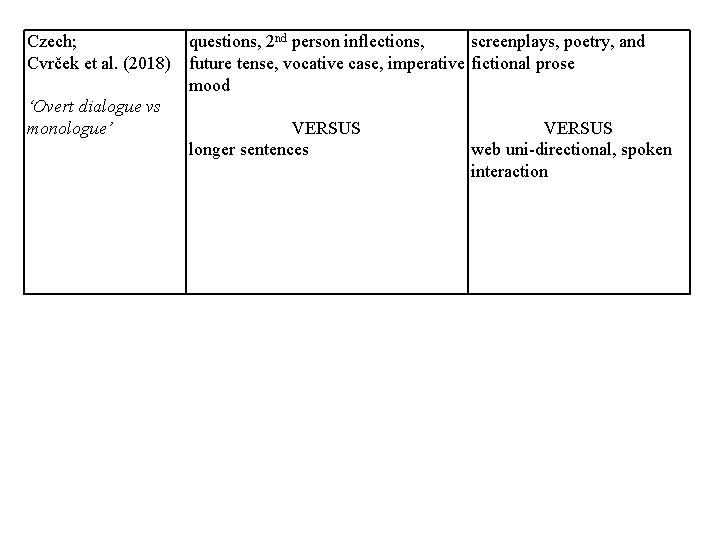

Czech; Cvrček et al. (2018) ‘Overt dialogue vs monologue’ questions, 2 nd person inflections, screenplays, poetry, and future tense, vocative case, imperative fictional prose mood VERSUS longer sentences VERSUS web uni directional, spoken interaction

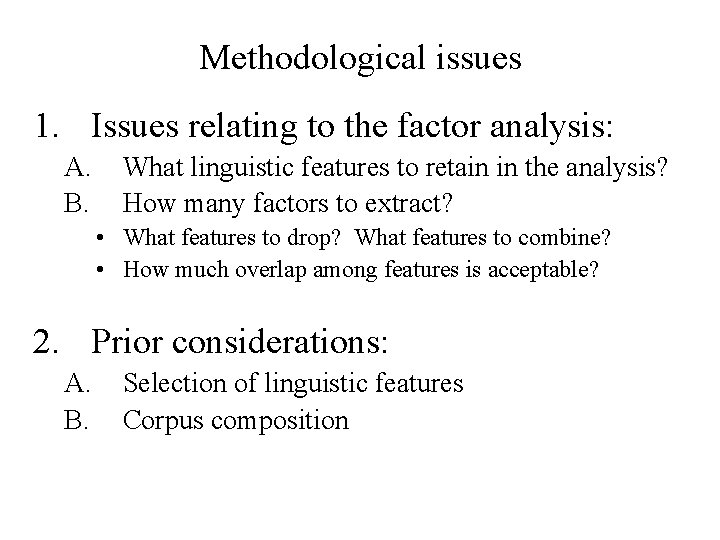

Methodological issues 1. Issues relating to the factor analysis: A. B. What linguistic features to retain in the analysis? How many factors to extract? • What features to drop? What features to combine? • How much overlap among features is acceptable? 2. Prior considerations: A. B. Selection of linguistic features Corpus composition

Prior considerations 1. Selection of linguistic features – – – Goal: be as inclusive as possible Lexical features: Include individual words? Collocations? Lexical bundles? Include features that are (completely? ) restricted to a few texts/registers?

Prior considerations 2. Corpus composition -- Three approaches: 1) Include ‘big enough’ samples from the range of registers – hope that balance does not have a major influence on the dimensions – e. g. , Biber 1988 2) Carefully match and ‘balance’ the sub samples from each register – i. e. , a careful stratified design with equal samples from each register – e. g. , Berber Sardinha, Kauffmann, and Acunzo (2012); Cvrček et al. (2018) 3) Select a large, random sample from the discourse domain – the proportions for each register mirror their proportions in the larger population e. g. , Biber and Egbert (2018) + How determine the set of registers to include?

Conclusion I The analysis of every language (and each specific discourse domain) reveals distinctive dimensions that are unique to that language/domain

Conclusion II But two dimensions are represented across discourse domains and across languages – These are candidates for cross linguistic universals = fundamental parameters of variation for human discourse – Narrative versus non narrative discourse • Past tense verbs, 3 rd person pronouns, time adverbials • Not so surprising – but no other ‘mode’ of discourse emerges as a dimension consistently across languages/domains – Oral vs literate discourse – much more surprising – A ‘perfect storm’ of intersecting factors: • Grammatical: clausal vs. phrasal • Purpose/style: involved/elaborated vs. informational/compressed • Production: real time vs. edited

- Slides: 72