Using discrete choice analysis to understand tradeoffs in

- Slides: 49

Using discrete choice analysis to understand tradeoffs in climate and air pollution Brian Sergi Doctoral Student, Engineering & Public Policy Advisors: Inês Azevedo, Alex Davis CEDM Annual Meeting May 24, 2017 Carnegie Mellon University

Motivation • Scientific agreement on the need to reduce emissions, but support required from the public • Power sector interventions likely to have some cost to consumers. . . what tradeoffs are individuals willing to make? 2 Carnegie Mellon University

Broad questions of interest • How do individuals value tradeoffs across climate change, air quality, and the cost of electricity? • How does providing information related to climate or health affect respondents’ preferences? • Are levels of air pollution a mediator of support for reducing air pollution or mitigating climate related emissions? Assessed using two similarly structured discrete choice studies in the United States and China 3 Carnegie Mellon University

Discrete choice studies • Stated preference survey in which respondents indicate preferences by making choices between discrete alternatives • Well-established method in marketing, transportation research (Train, 2009) • Emerging method in the energy & environment space: • Climate change and energy security (Longo et. al. , 2008) • Estimating implicit discount rates for lighting (Min et. al. , 2014) • Preferences for electric vehicles (Helveston et. al. , 2015) • Energy efficiency (Davis & Metcalf, 2014) • Renewables and electricity bills in Germany (Kaenzig et. al. , 2013) • Preferences for electricity generation in Korea (Byun & Lee, 2017) • Our survey: Individuals respond to 16 comparisons of discrete electricity “futures” with different attribute levels 4 Carnegie Mellon University

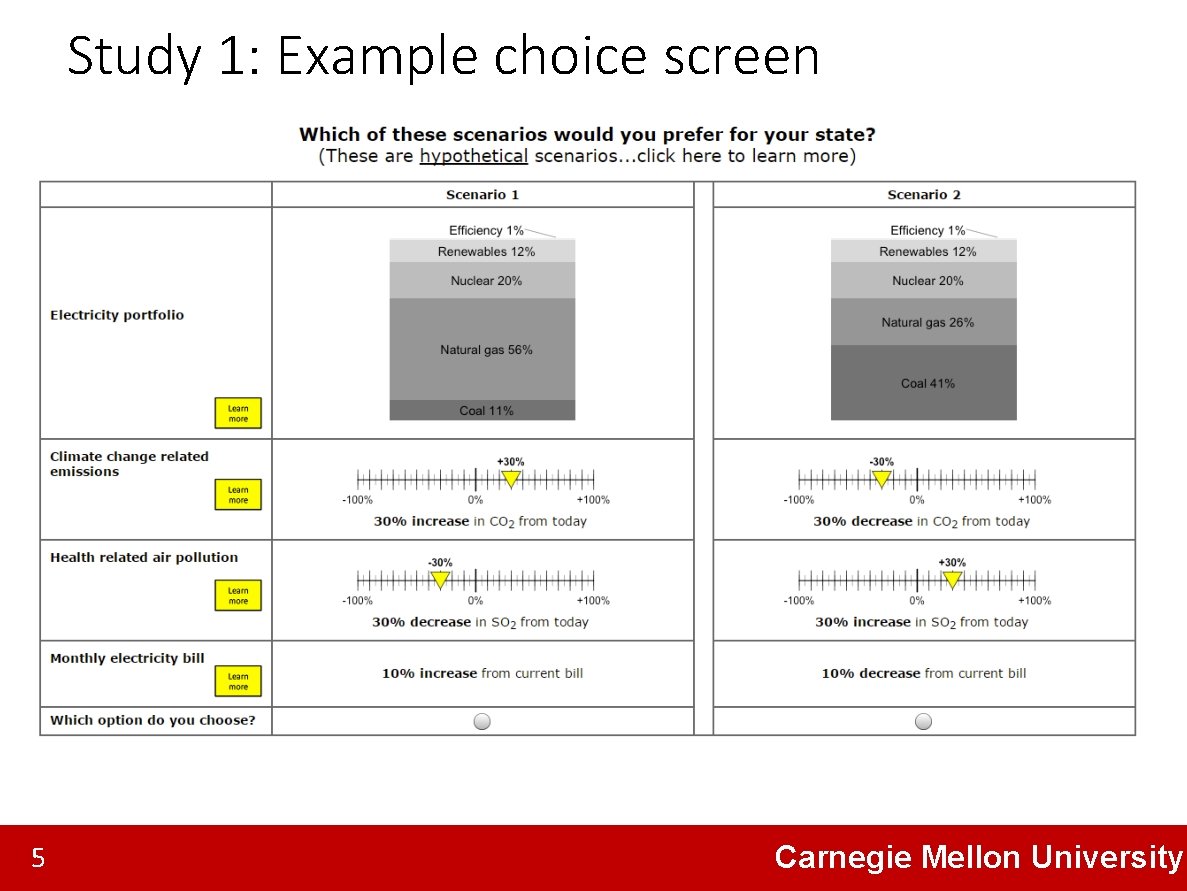

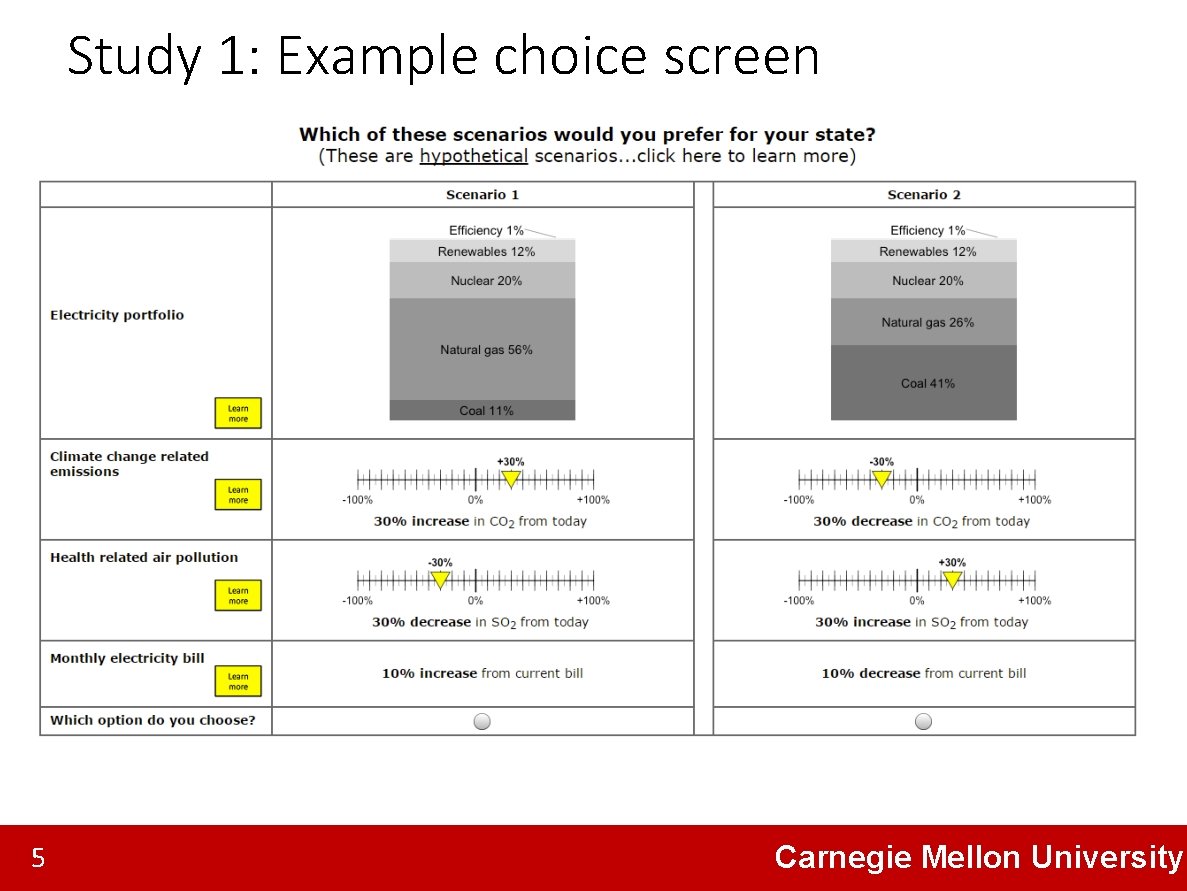

Study 1: Example choice screen 5 Carnegie Mellon University

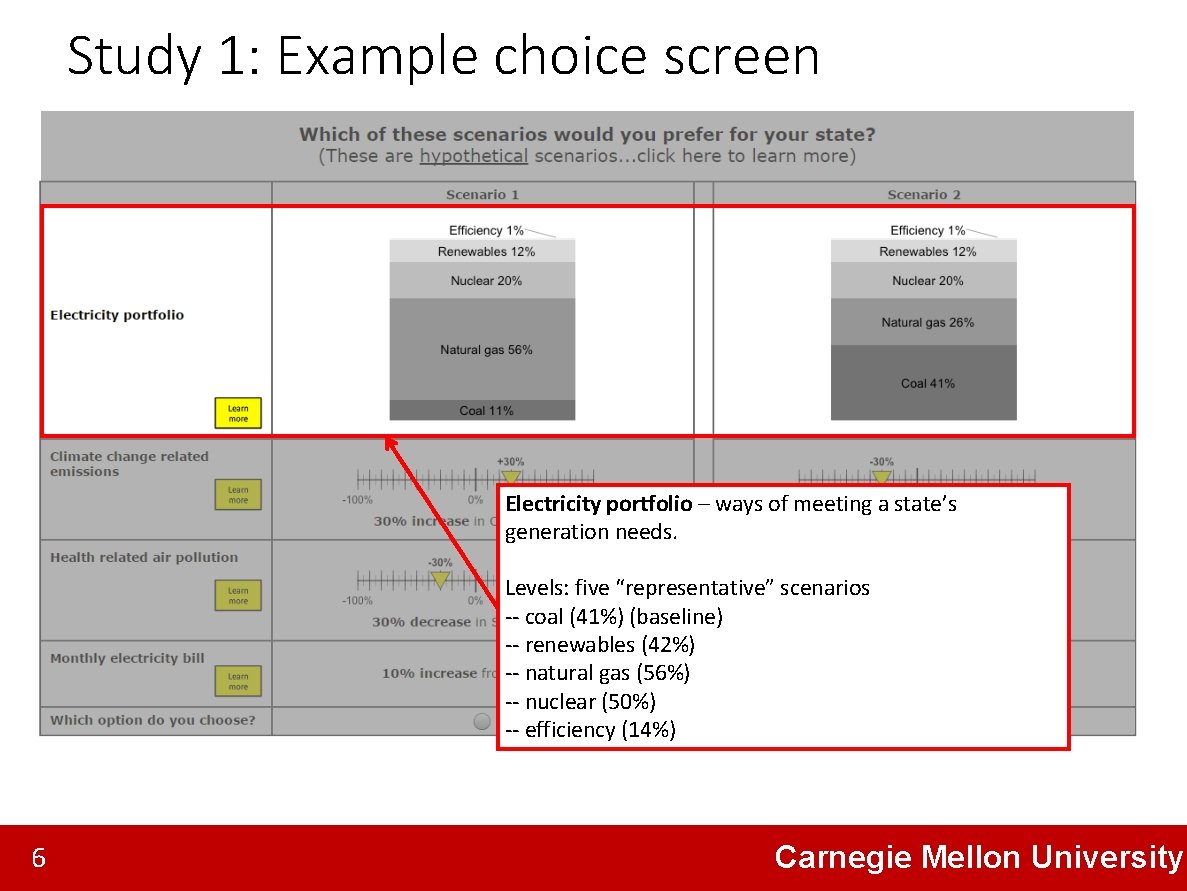

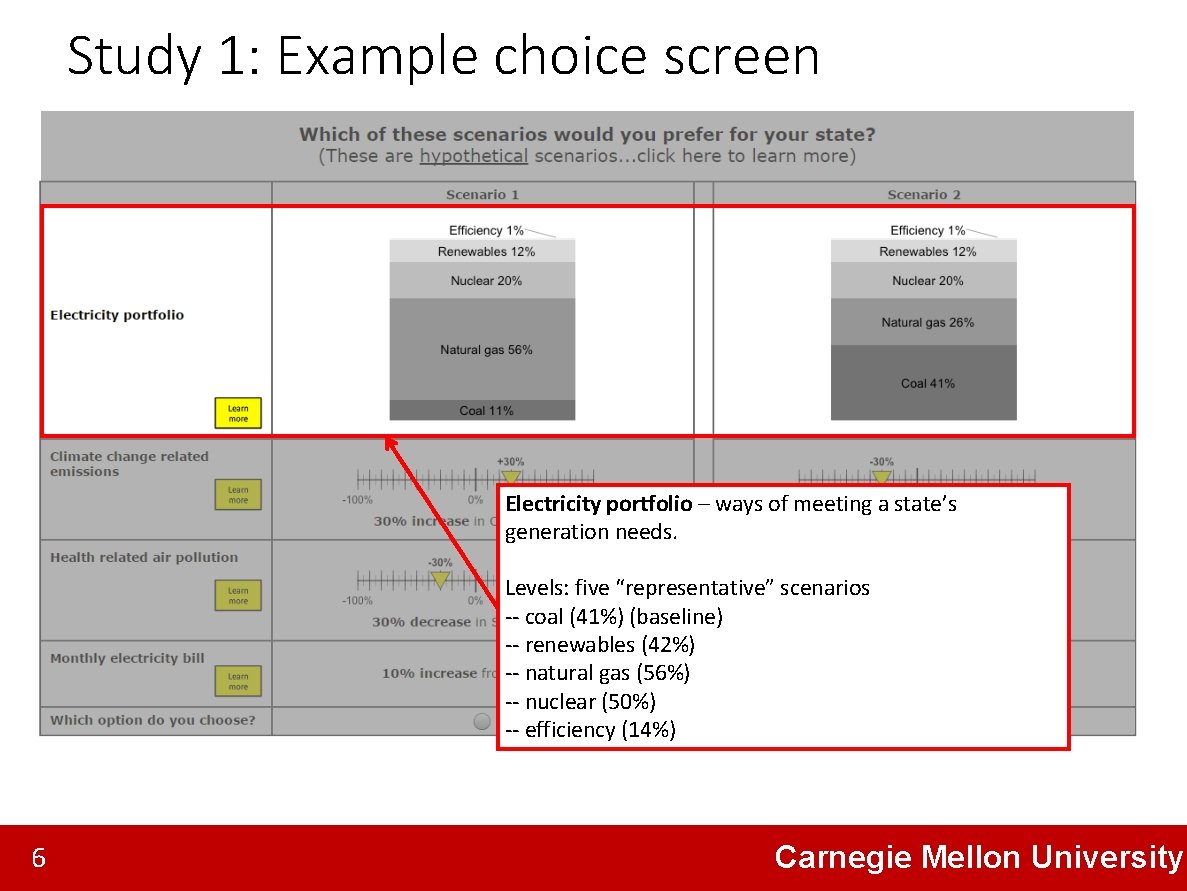

Study 1: Example choice screen Electricity portfolio – ways of meeting a state’s generation needs. Levels: five “representative” scenarios -- coal (41%) (baseline) -- renewables (42%) -- natural gas (56%) -- nuclear (50%) -- efficiency (14%) 6 Carnegie Mellon University

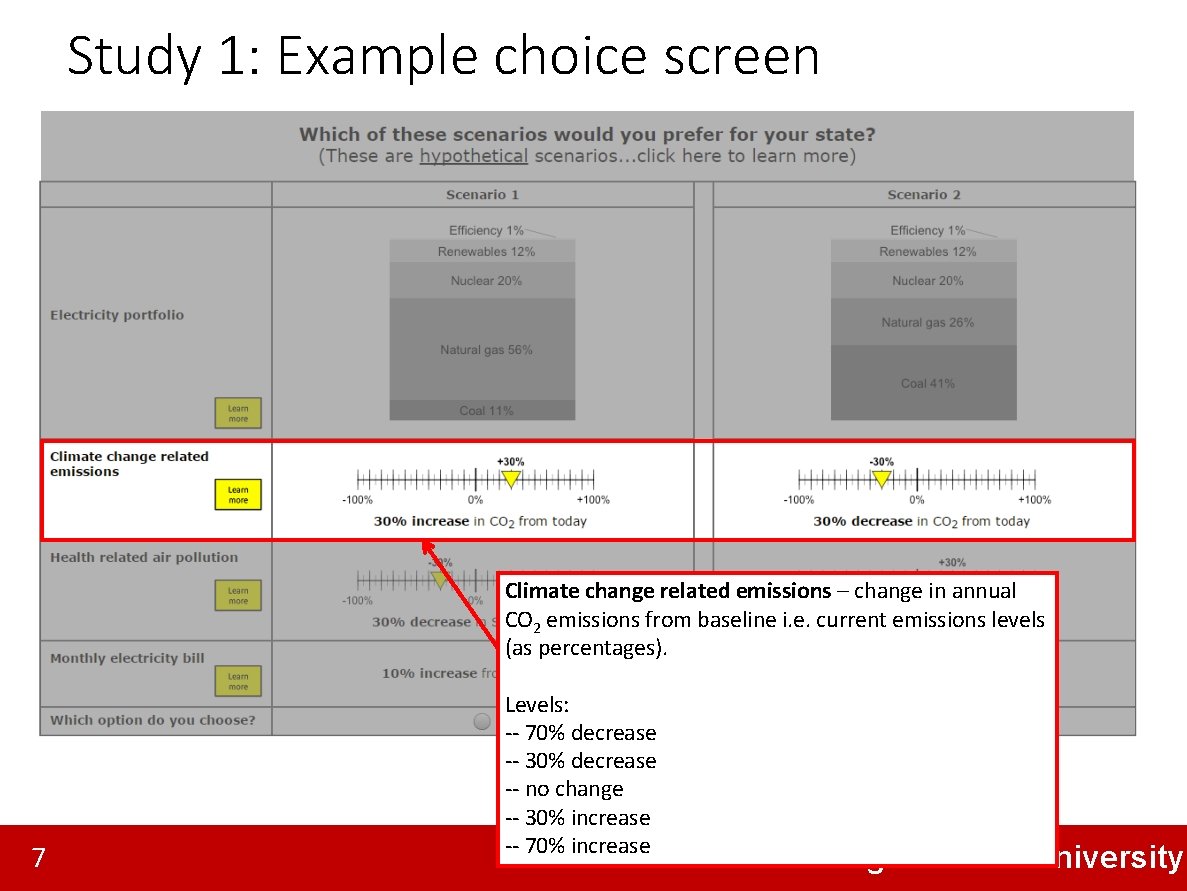

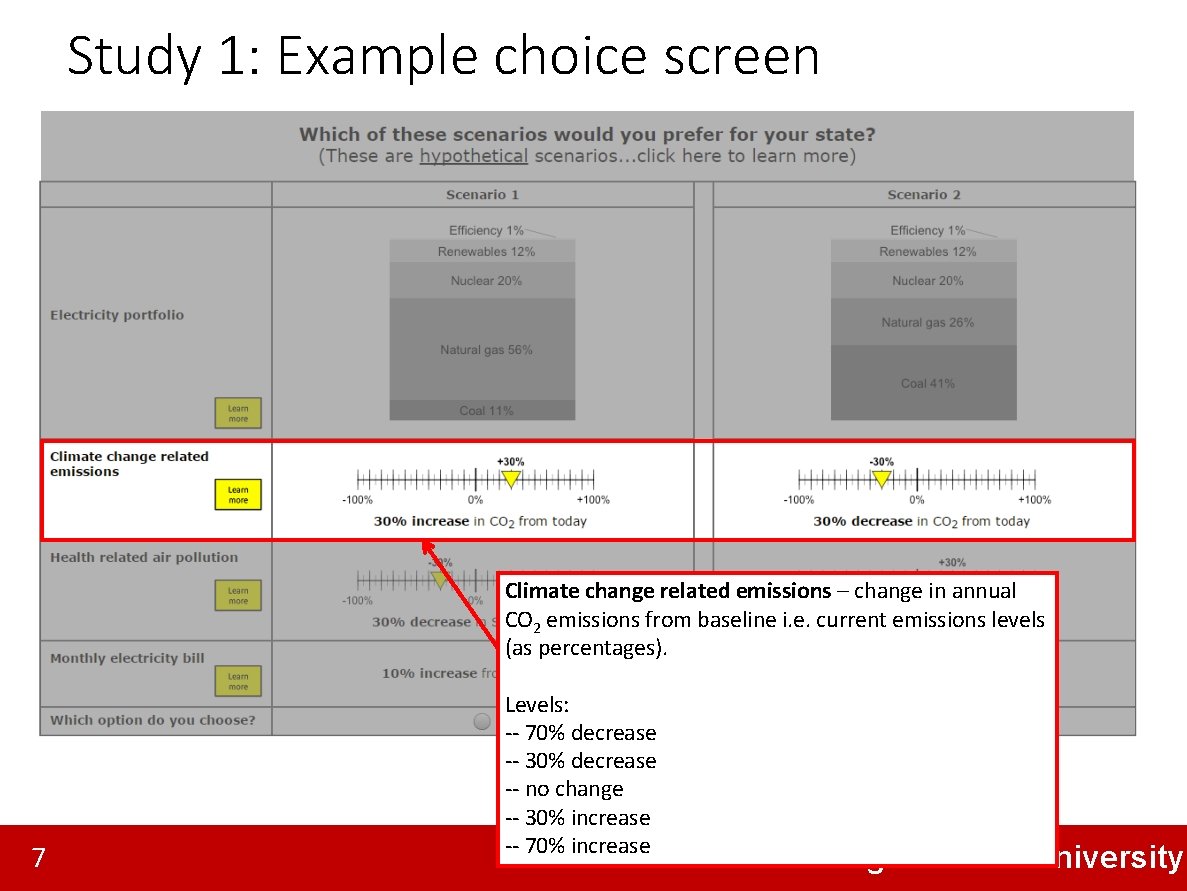

Study 1: Example choice screen Climate change related emissions – change in annual CO 2 emissions from baseline i. e. current emissions levels (as percentages). 7 Levels: -- 70% decrease -- 30% decrease -- no change -- 30% increase -- 70% increase Carnegie Mellon University

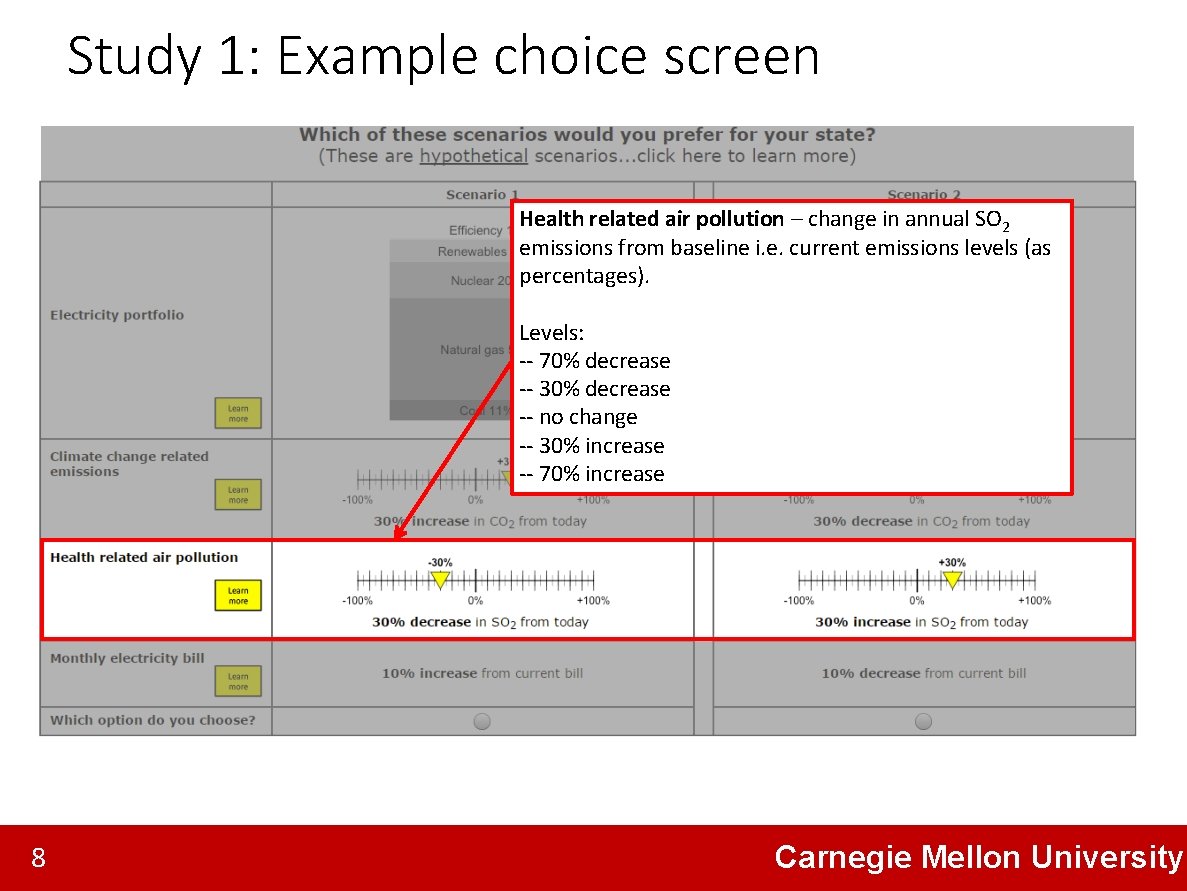

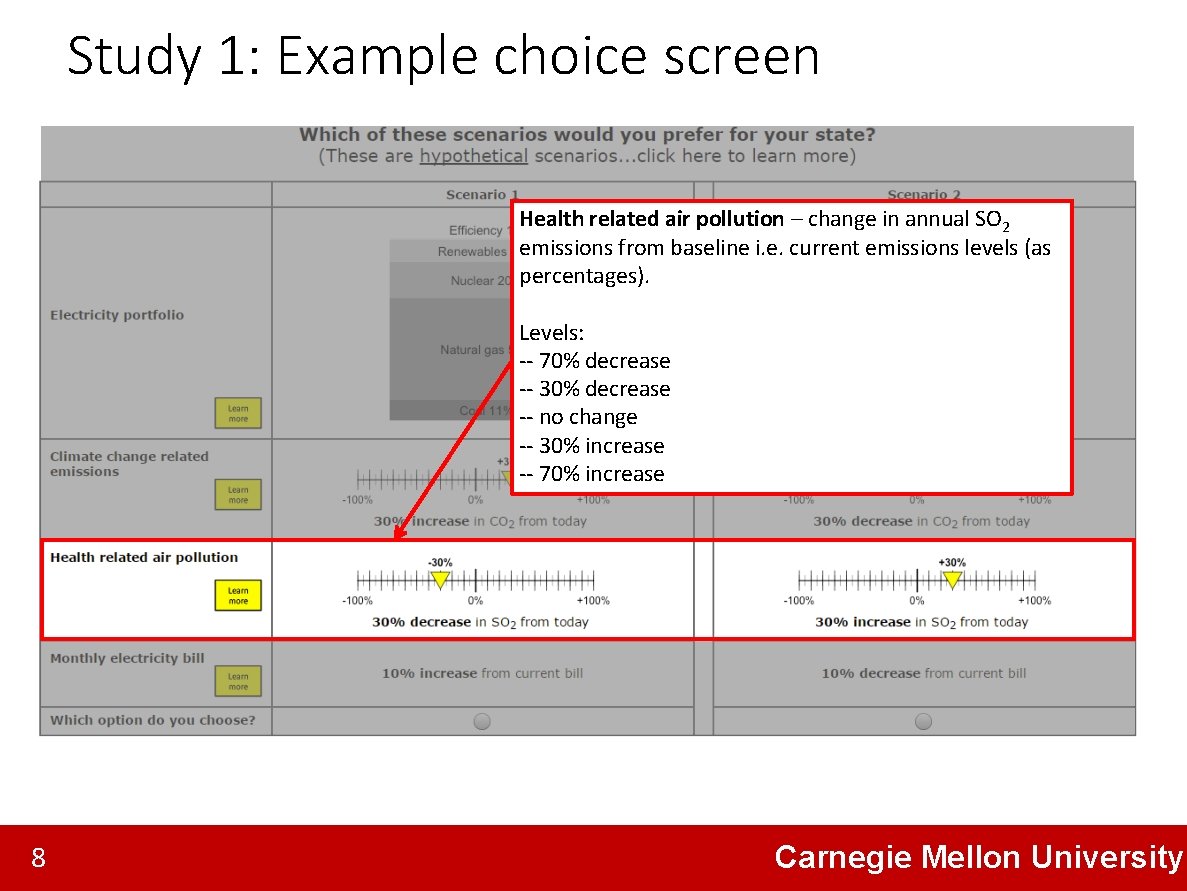

Study 1: Example choice screen Health related air pollution – change in annual SO 2 emissions from baseline i. e. current emissions levels (as percentages). Levels: -- 70% decrease -- 30% decrease -- no change -- 30% increase -- 70% increase 8 Carnegie Mellon University

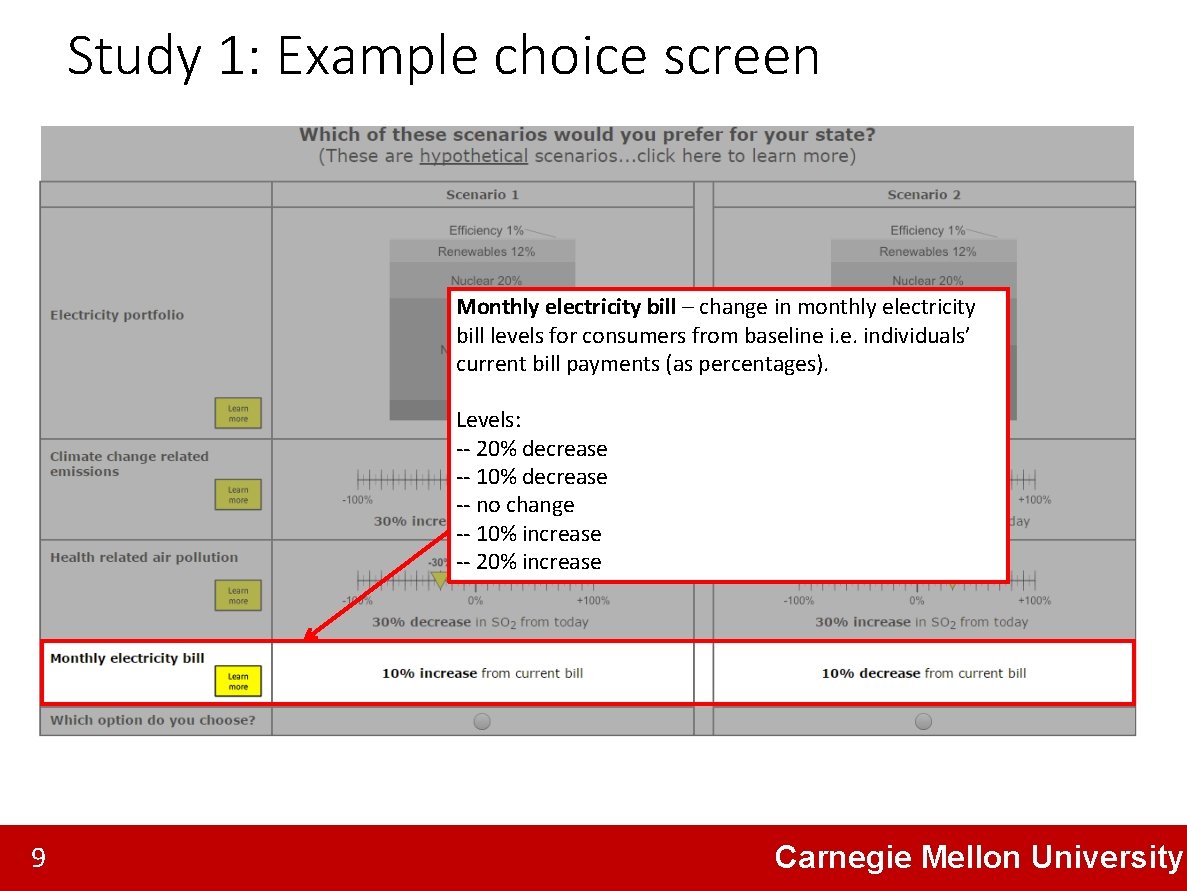

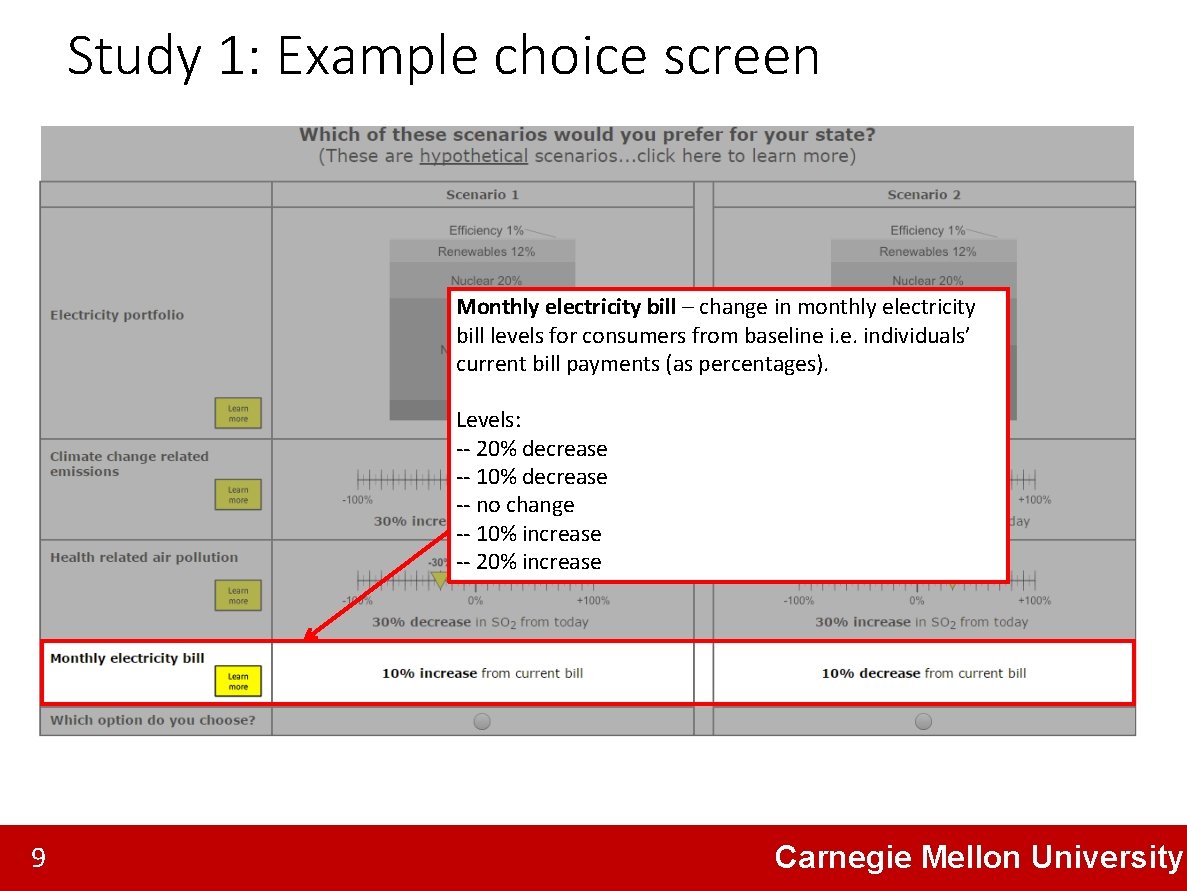

Study 1: Example choice screen Monthly electricity bill – change in monthly electricity bill levels for consumers from baseline i. e. individuals’ current bill payments (as percentages). Levels: -- 20% decrease -- 10% decrease -- no change -- 10% increase -- 20% increase 9 Carnegie Mellon University

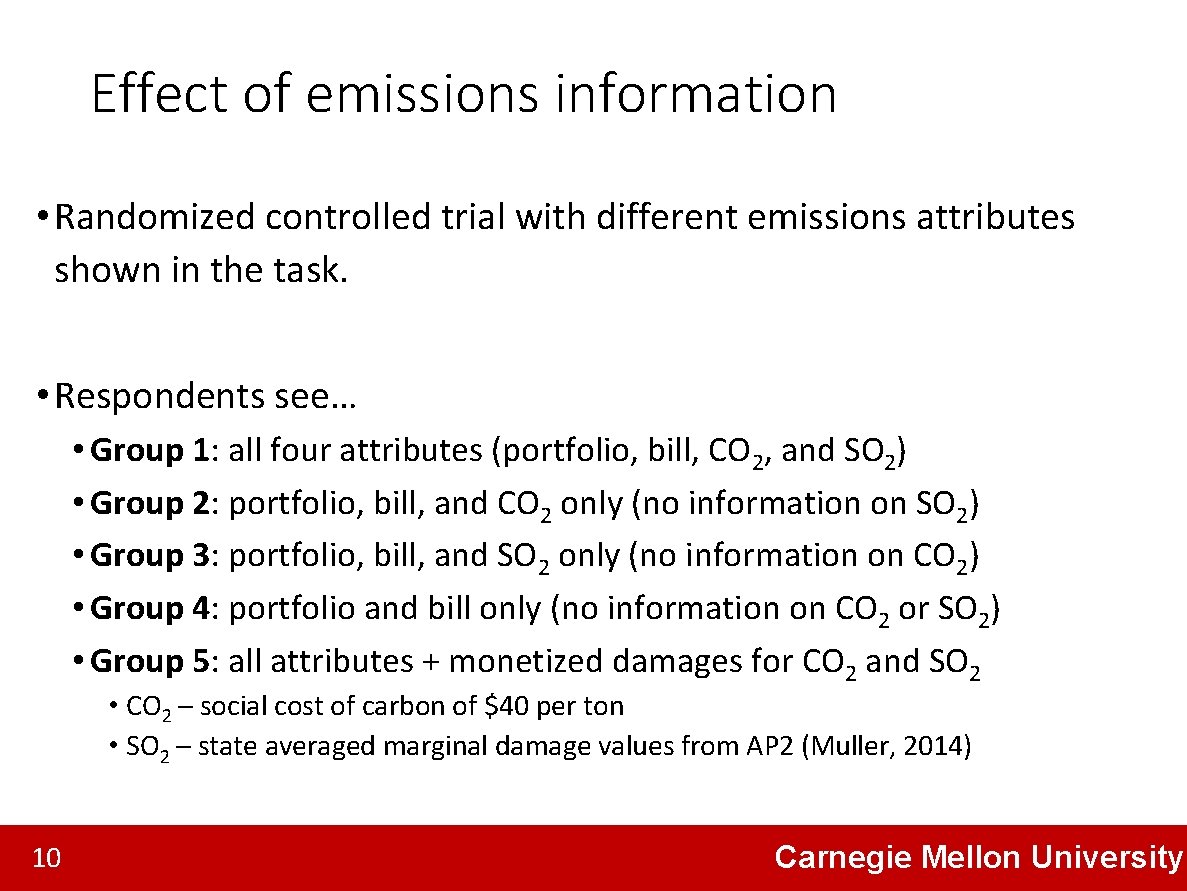

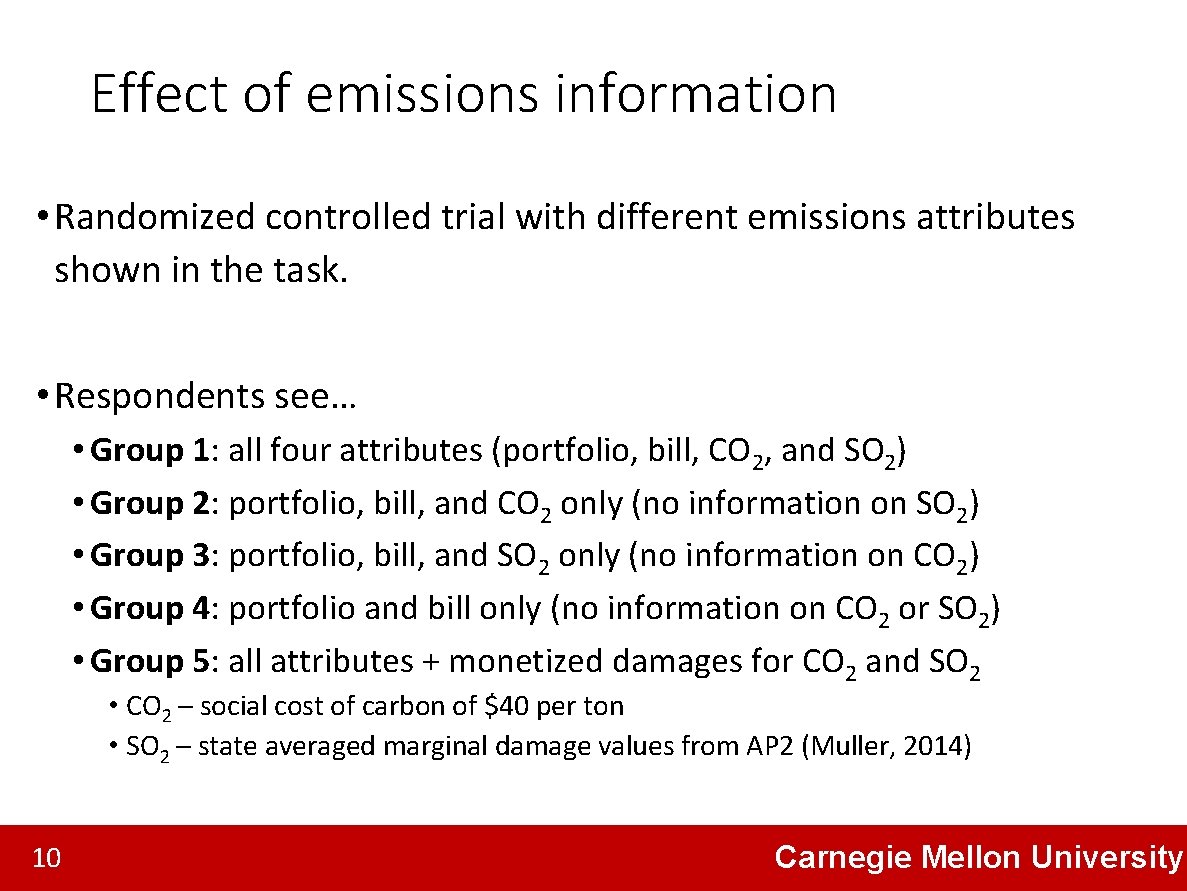

Effect of emissions information • Randomized controlled trial with different emissions attributes shown in the task. • Respondents see… • Group 1: all four attributes (portfolio, bill, CO 2, and SO 2) • Group 2: portfolio, bill, and CO 2 only (no information on SO 2) • Group 3: portfolio, bill, and SO 2 only (no information on CO 2) • Group 4: portfolio and bill only (no information on CO 2 or SO 2) • Group 5: all attributes + monetized damages for CO 2 and SO 2 • CO 2 – social cost of carbon of $40 per ton • SO 2 – state averaged marginal damage values from AP 2 (Muller, 2014) 10 Carnegie Mellon University

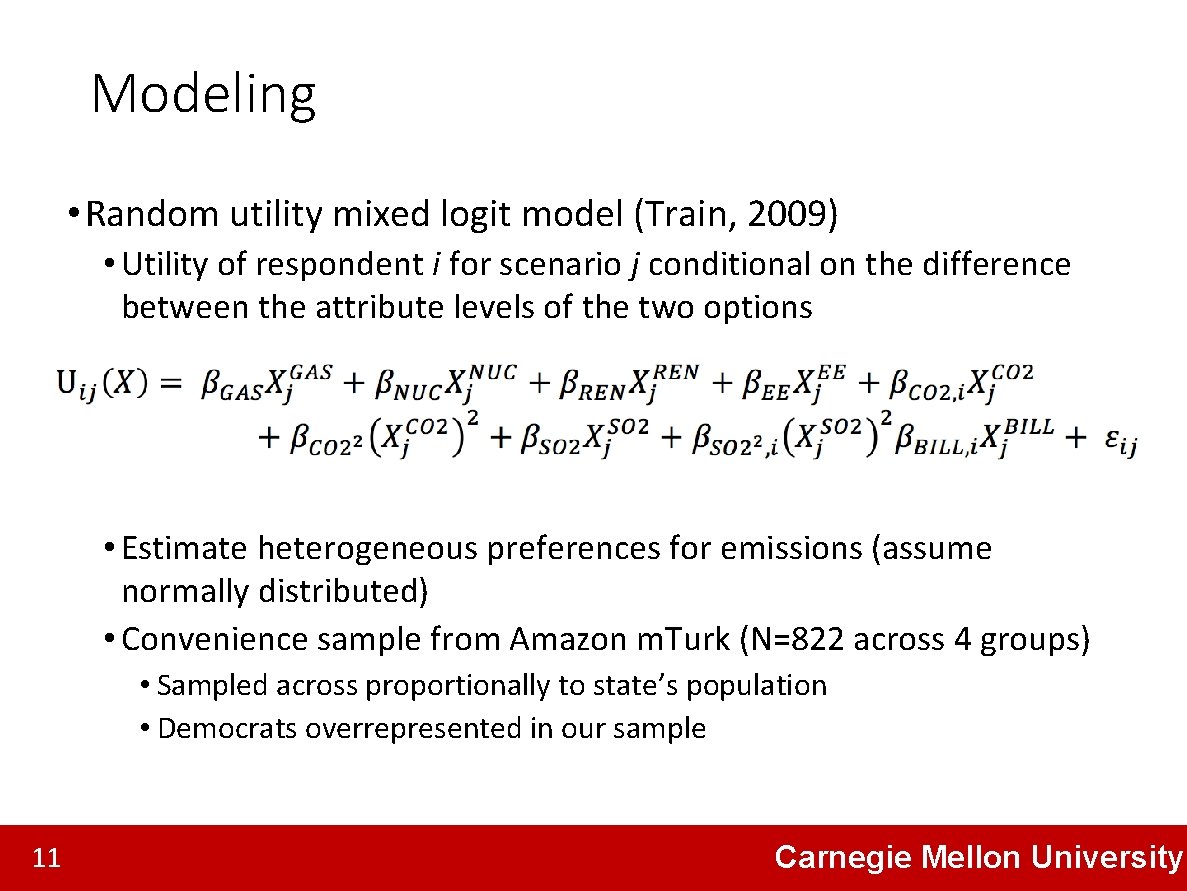

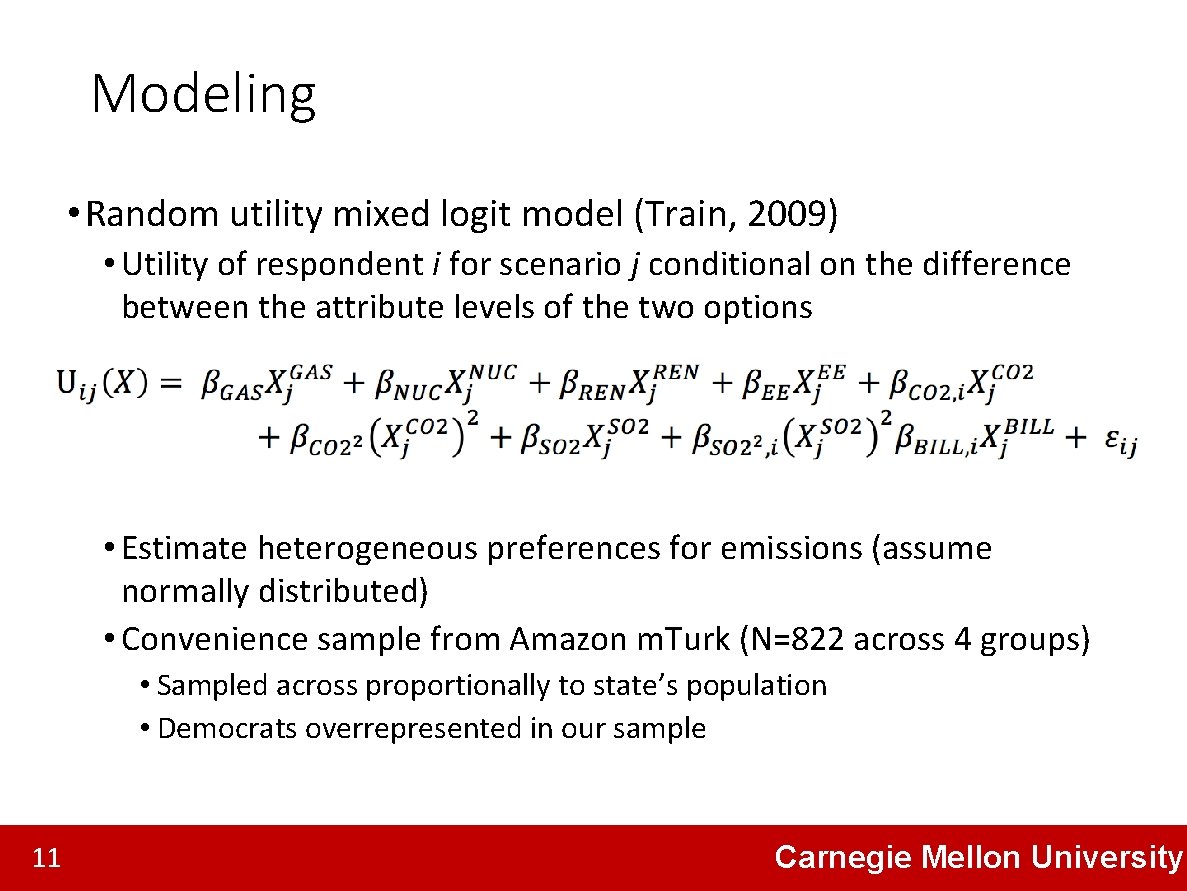

Modeling • Random utility mixed logit model (Train, 2009) • Utility of respondent i for scenario j conditional on the difference between the attribute levels of the two options • Estimate heterogeneous preferences for emissions (assume normally distributed) • Convenience sample from Amazon m. Turk (N=822 across 4 groups) • Sampled across proportionally to state’s population • Democrats overrepresented in our sample 11 Carnegie Mellon University

Results • Probability of support for scenarios with emissions reductions • Willingness to pay (% increase in monthly electricity and implied $ per ton) 12 Carnegie Mellon University

Support for renewables with 20% increase in electricity bills 13 Carnegie Mellon University

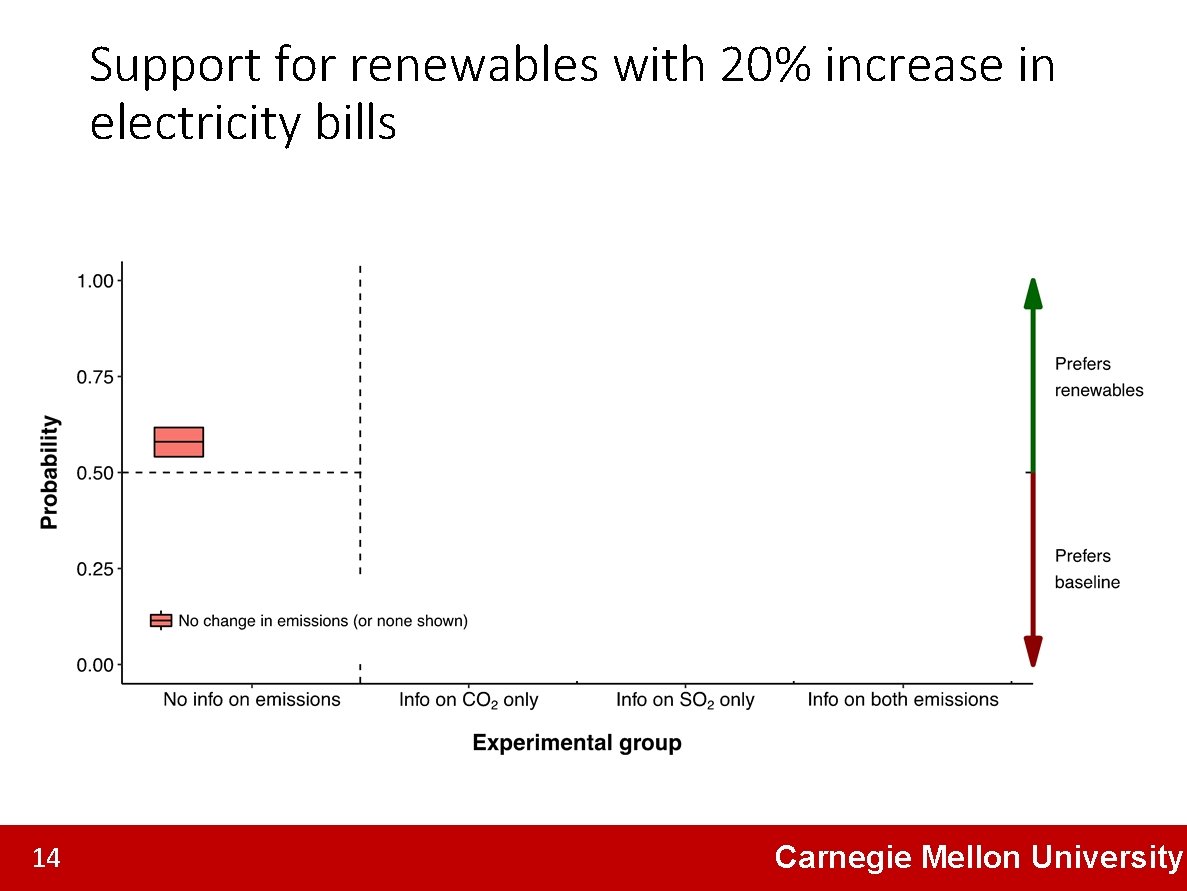

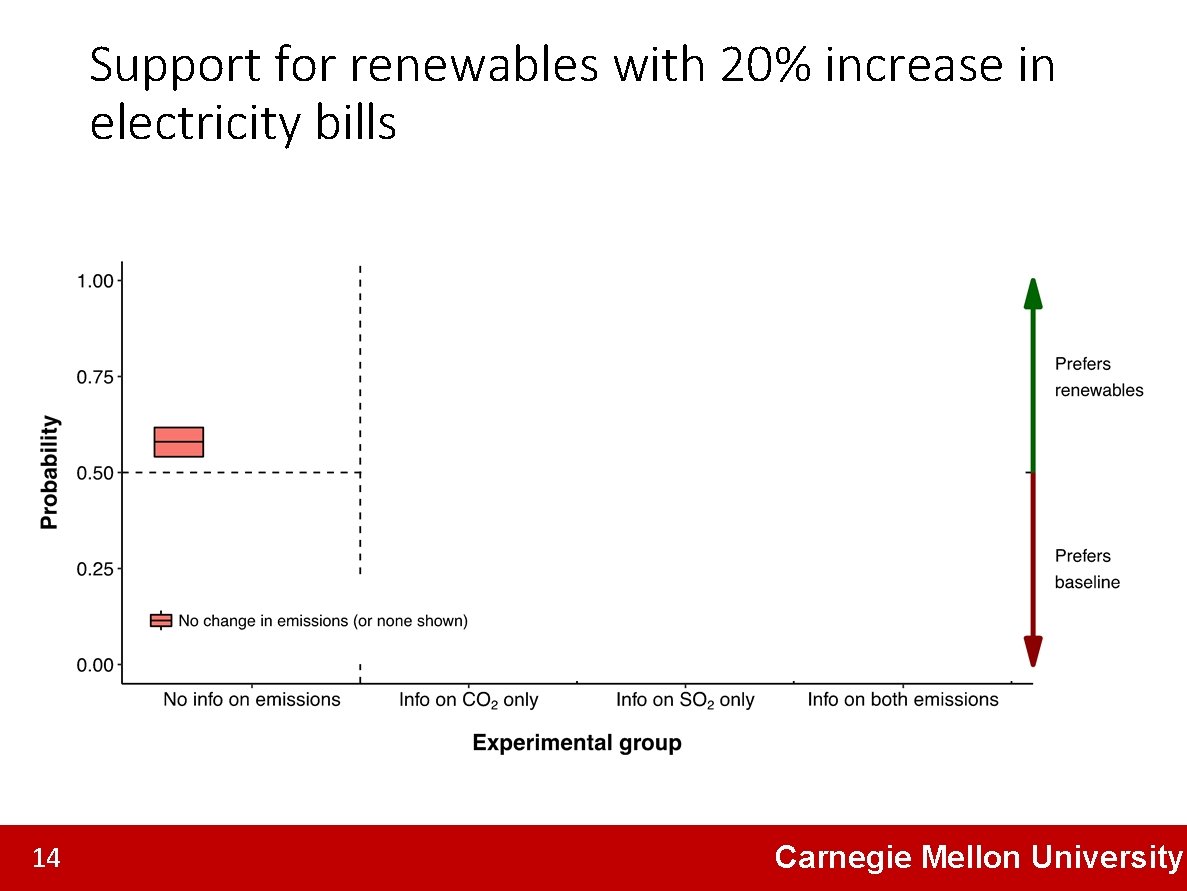

Support for renewables with 20% increase in electricity bills 14 Carnegie Mellon University

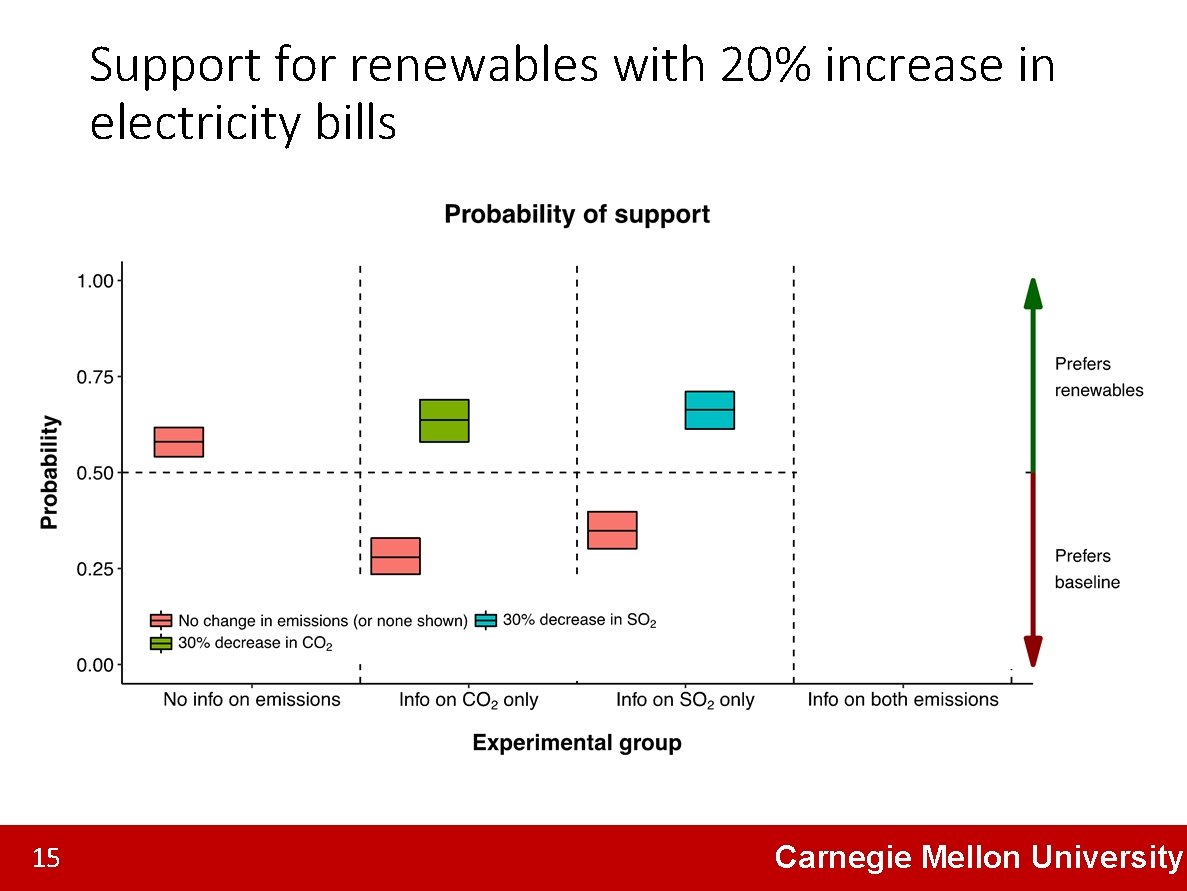

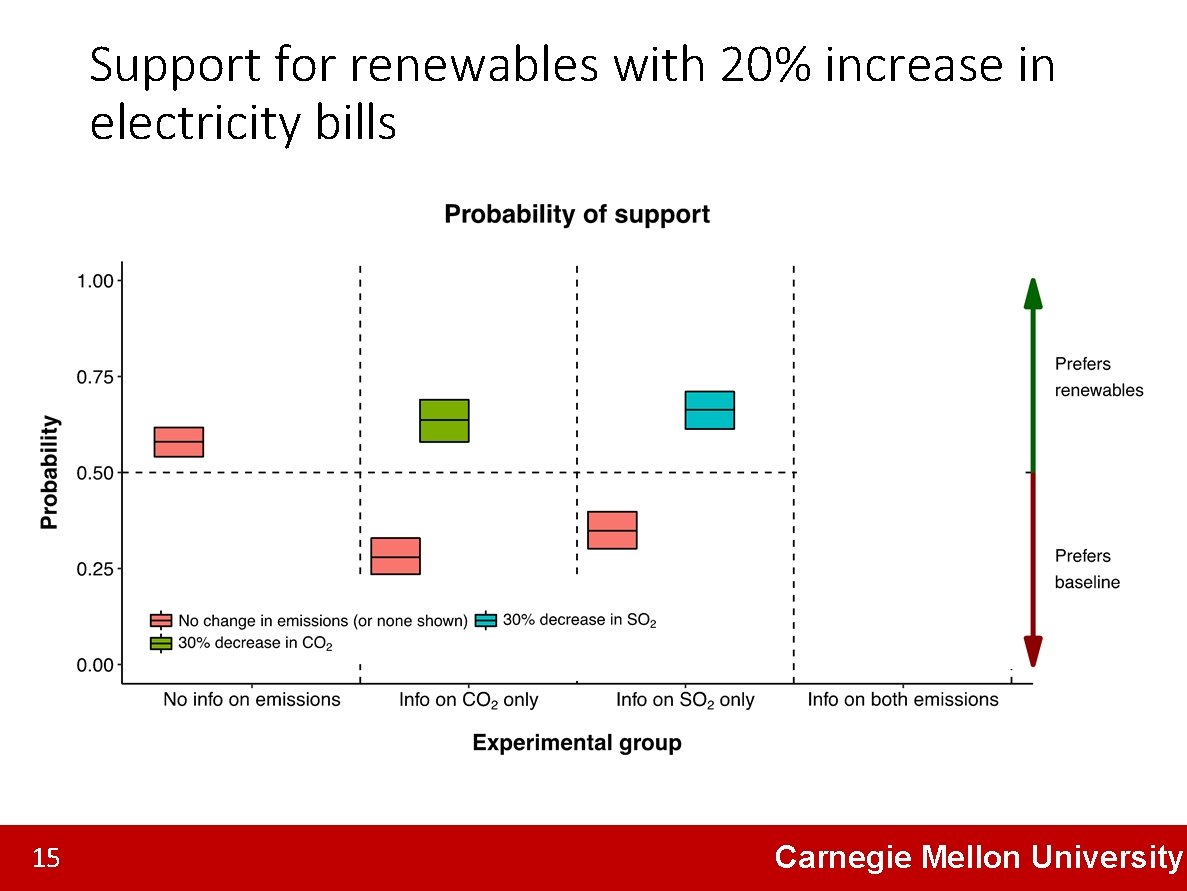

Support for renewables with 20% increase in electricity bills 15 Carnegie Mellon University

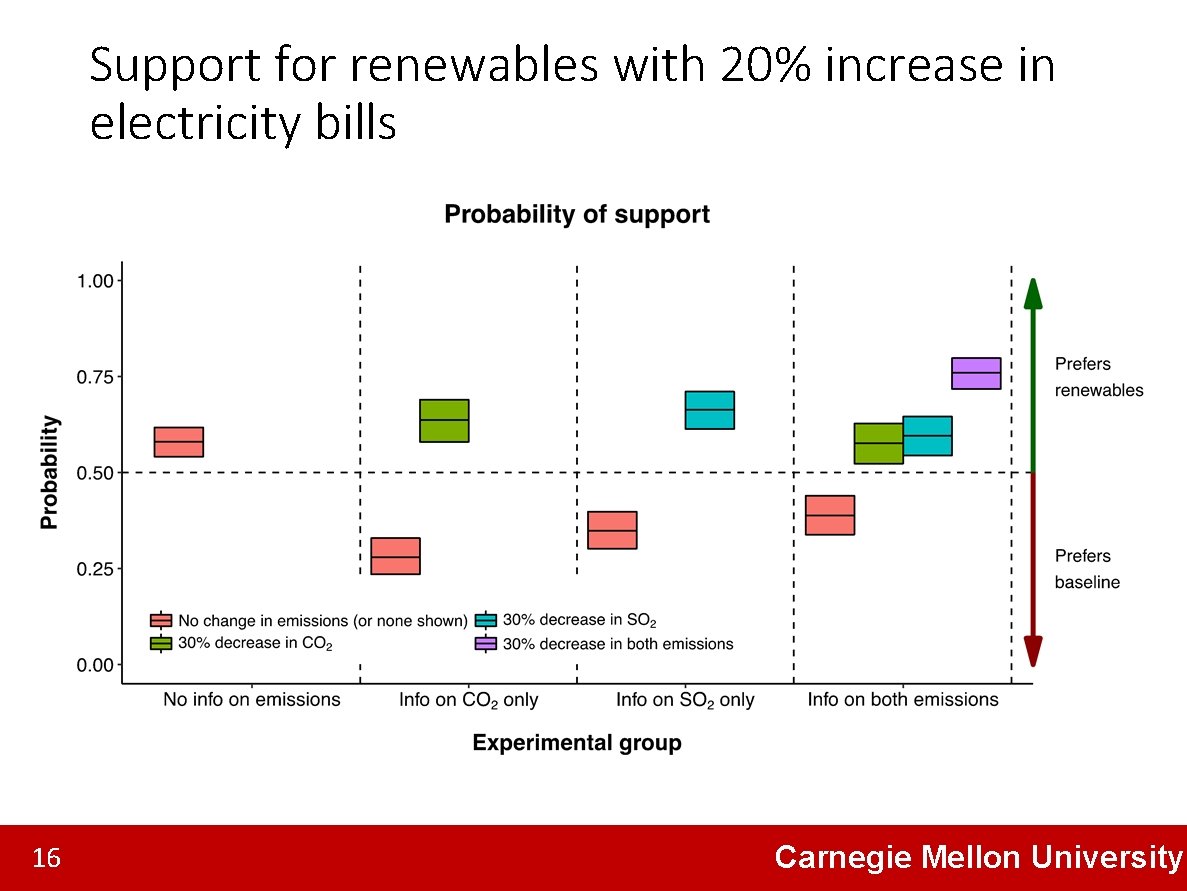

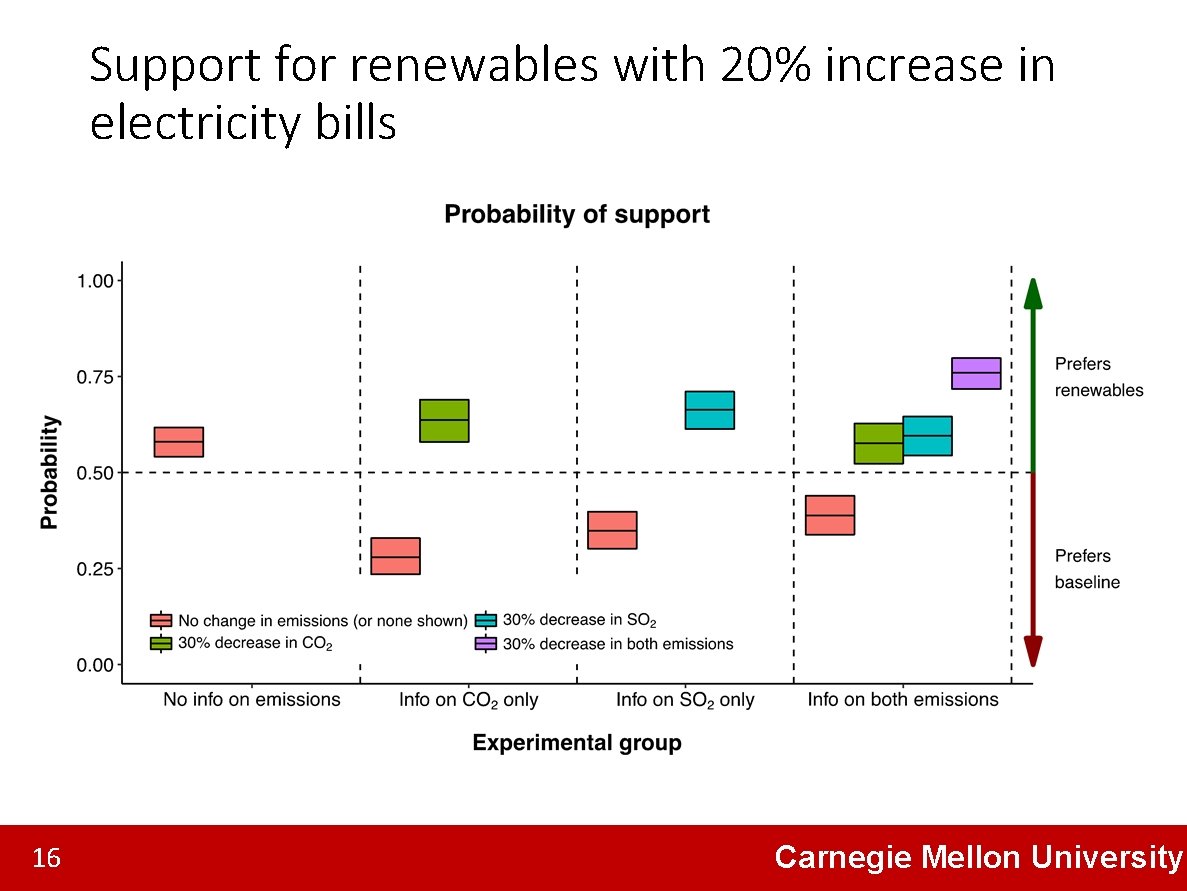

Support for renewables with 20% increase in electricity bills 16 Carnegie Mellon University

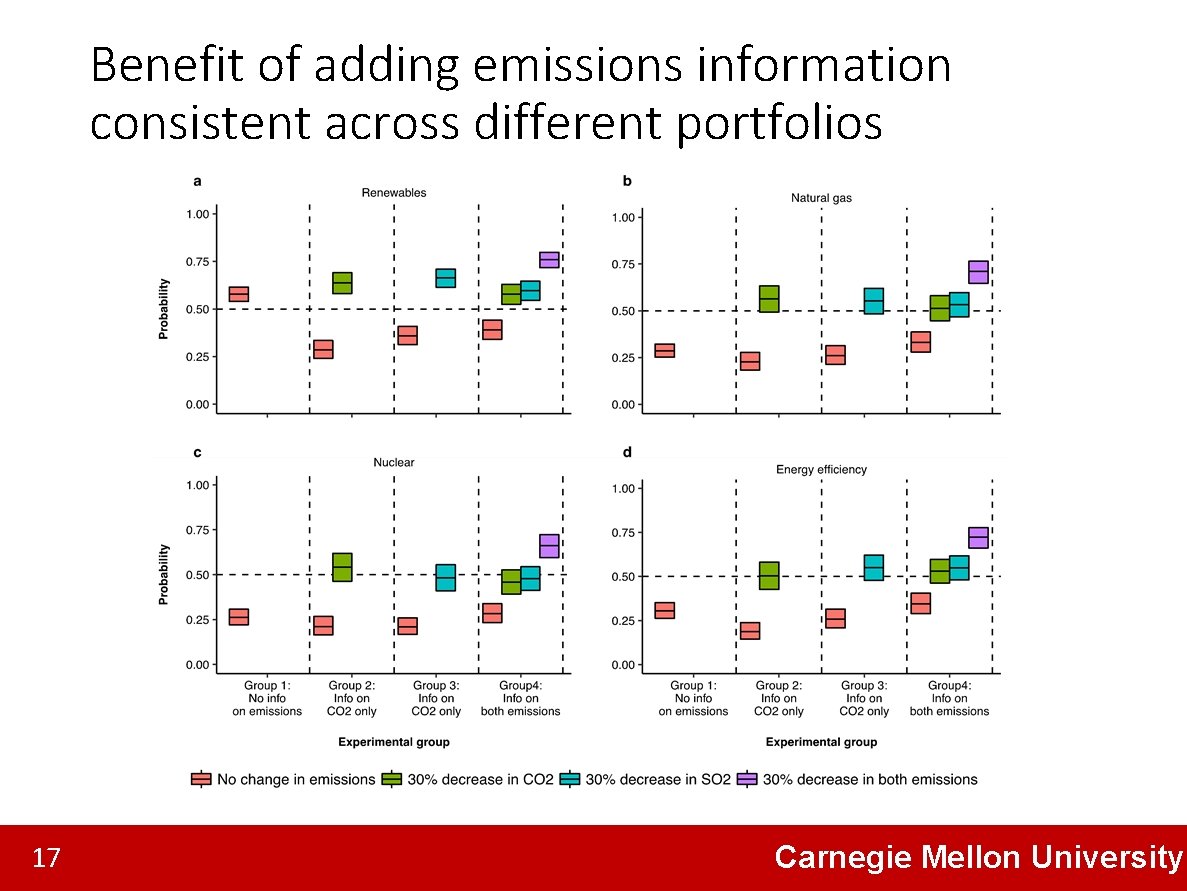

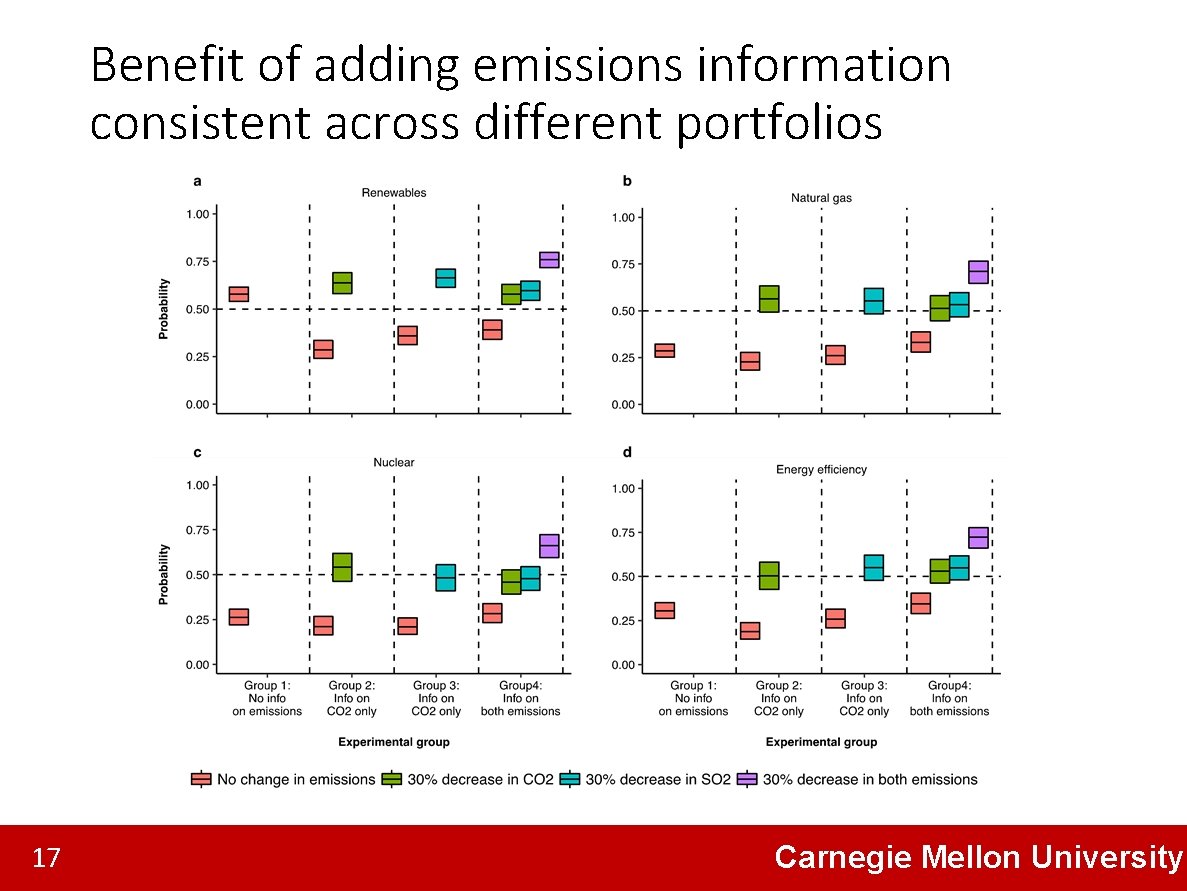

Benefit of adding emissions information consistent across different portfolios 17 Carnegie Mellon University

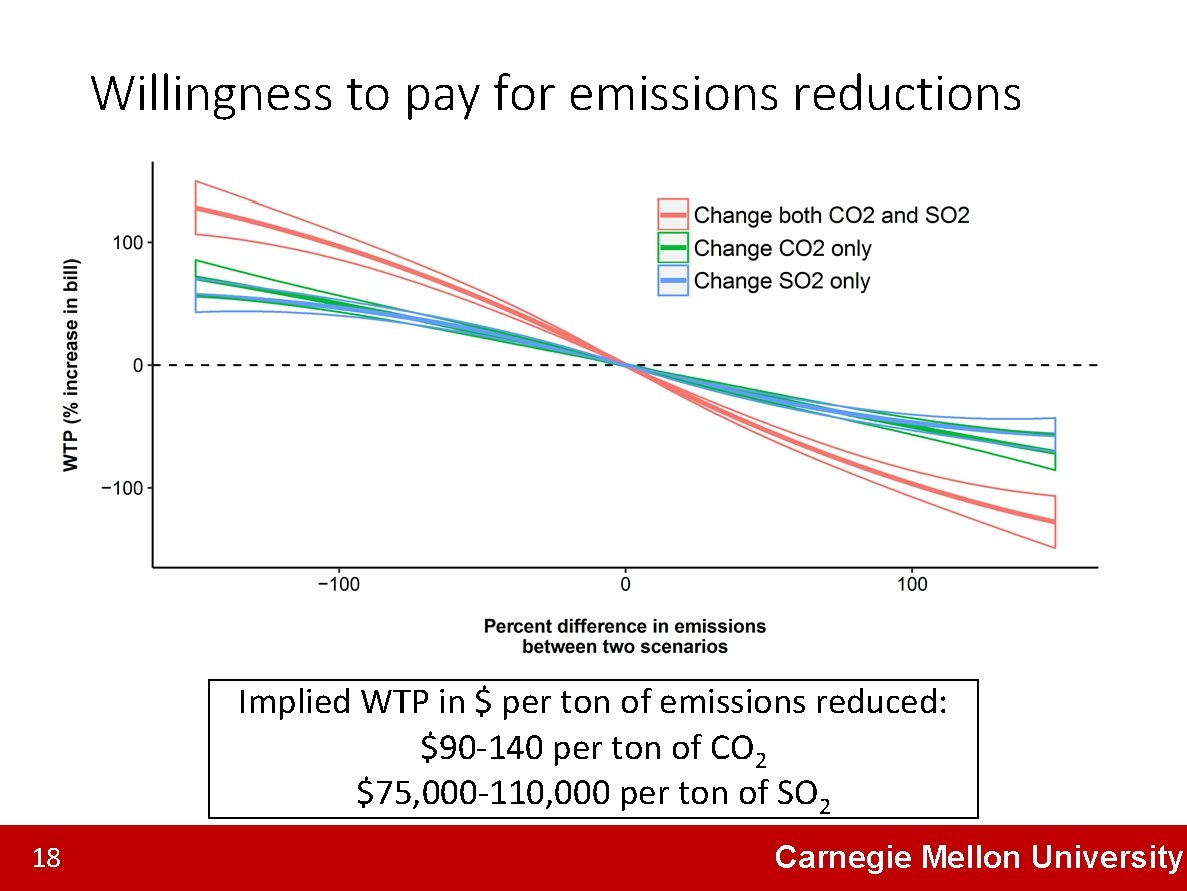

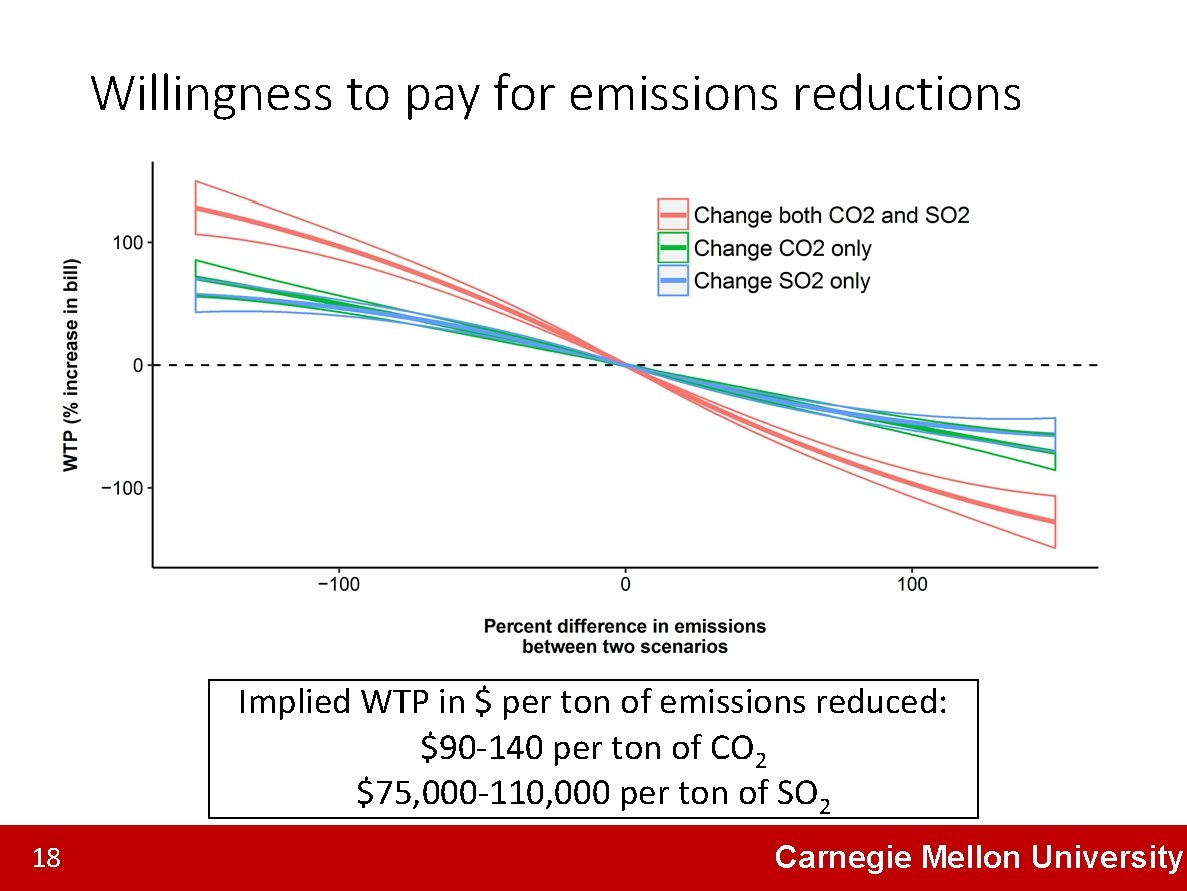

Willingness to pay for emissions reductions Implied WTP in $ per ton of emissions reduced: $90 -140 per ton of CO 2 $75, 000 -110, 000 per ton of SO 2 18 Carnegie Mellon University

Summary of findings – Study 1 • Public willing to support more expensive scenarios if they yield emissions reductions • Combined information from both climate and health related emissions elicits more support than one alone • Respondents performed well on attention and comprehension tasks within the survey • Difficult to discern any patterns in demographics, state level heterogeneity 19 Carnegie Mellon University

Study 2: Public perceptions of climate change and air pollution in China Brian Sergi, Inês Azevedo, Alex Davis XU Jianhua (徐建华), XIA Tian (夏田) 20 Carnegie Mellon University

Growing public pressure in China to act on emissions Source: The Economist Source: “Green protests on the rise in China” Nature News 21 Carnegie Mellon University

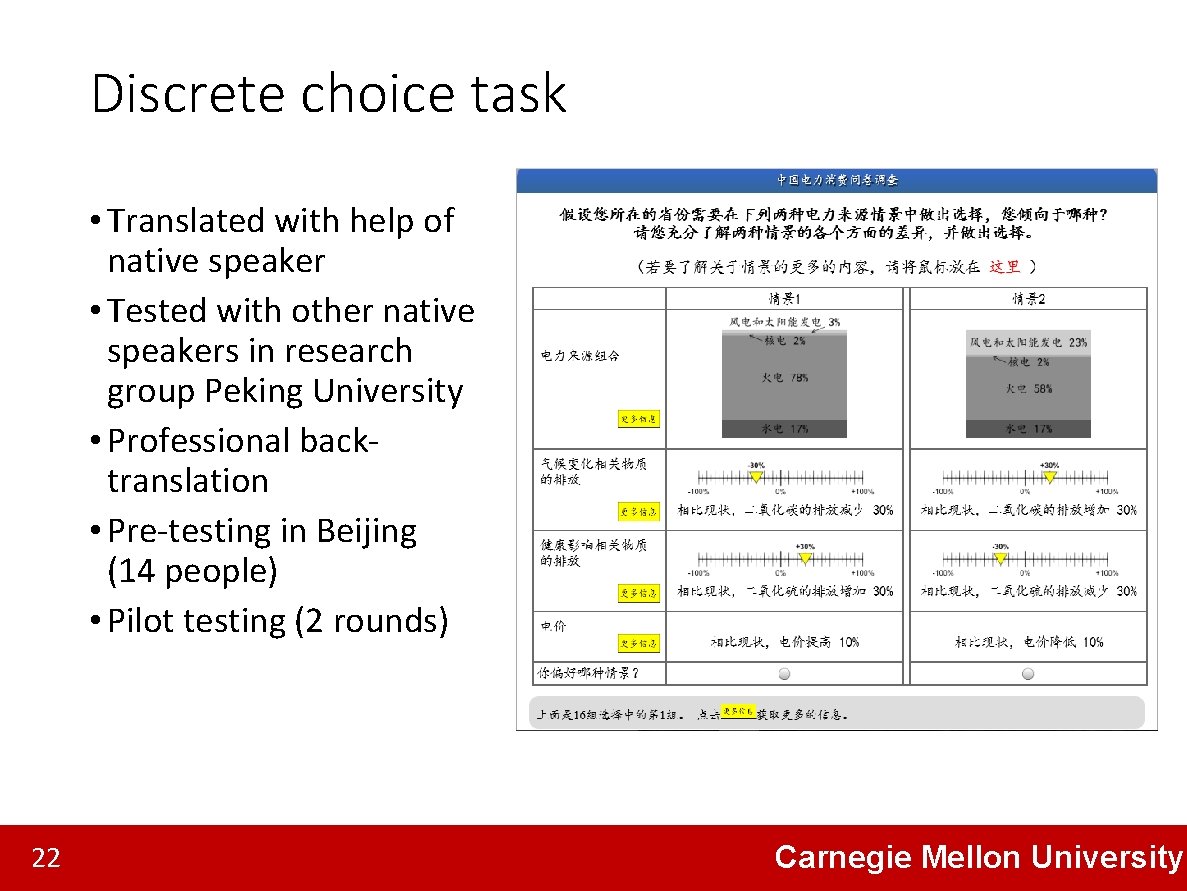

Discrete choice task • Translated with help of native speaker • Tested with other native speakers in research group Peking University • Professional backtranslation • Pre-testing in Beijing (14 people) • Pilot testing (2 rounds) 22 Carnegie Mellon University

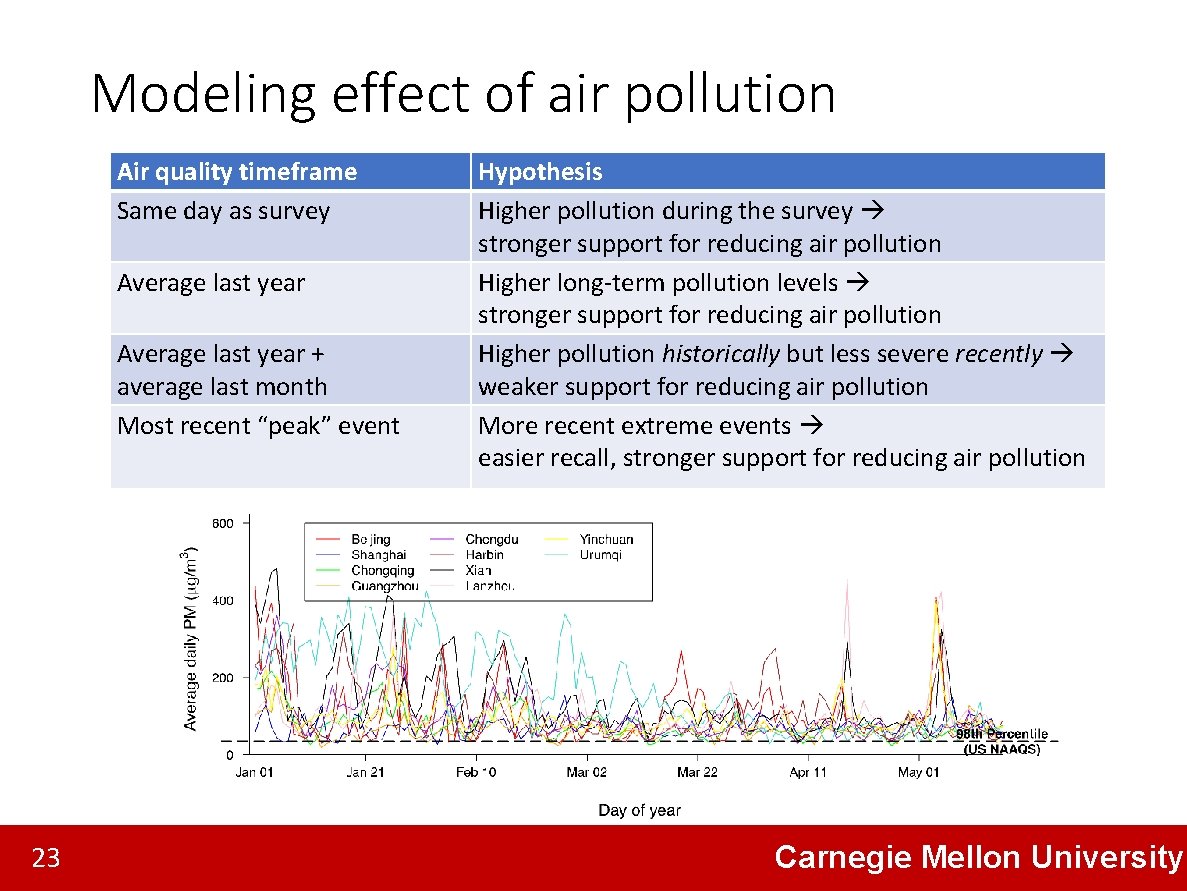

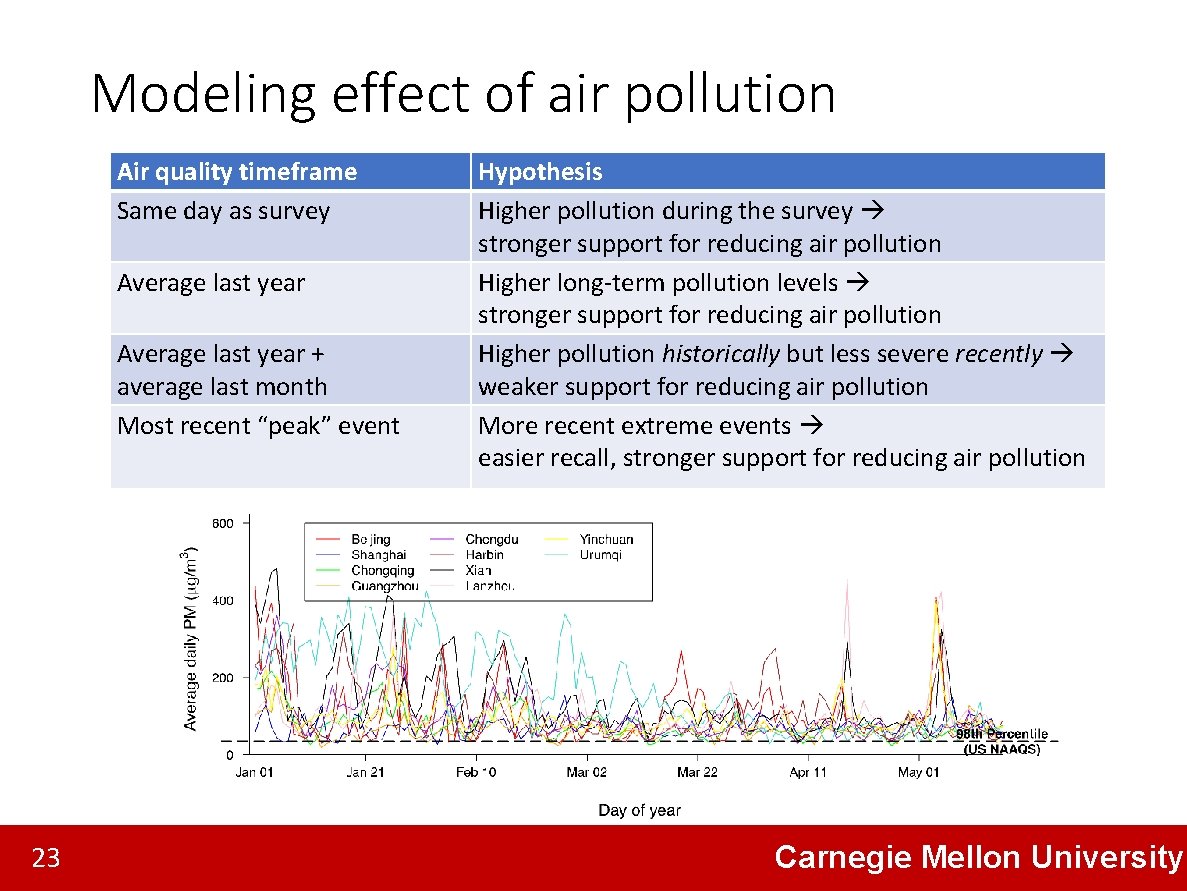

Modeling effect of air pollution Air quality timeframe Same day as survey Average last year + average last month Most recent “peak” event 23 Hypothesis Higher pollution during the survey stronger support for reducing air pollution Higher long-term pollution levels stronger support for reducing air pollution Higher pollution historically but less severe recently weaker support for reducing air pollution More recent extreme events easier recall, stronger support for reducing air pollution Carnegie Mellon University

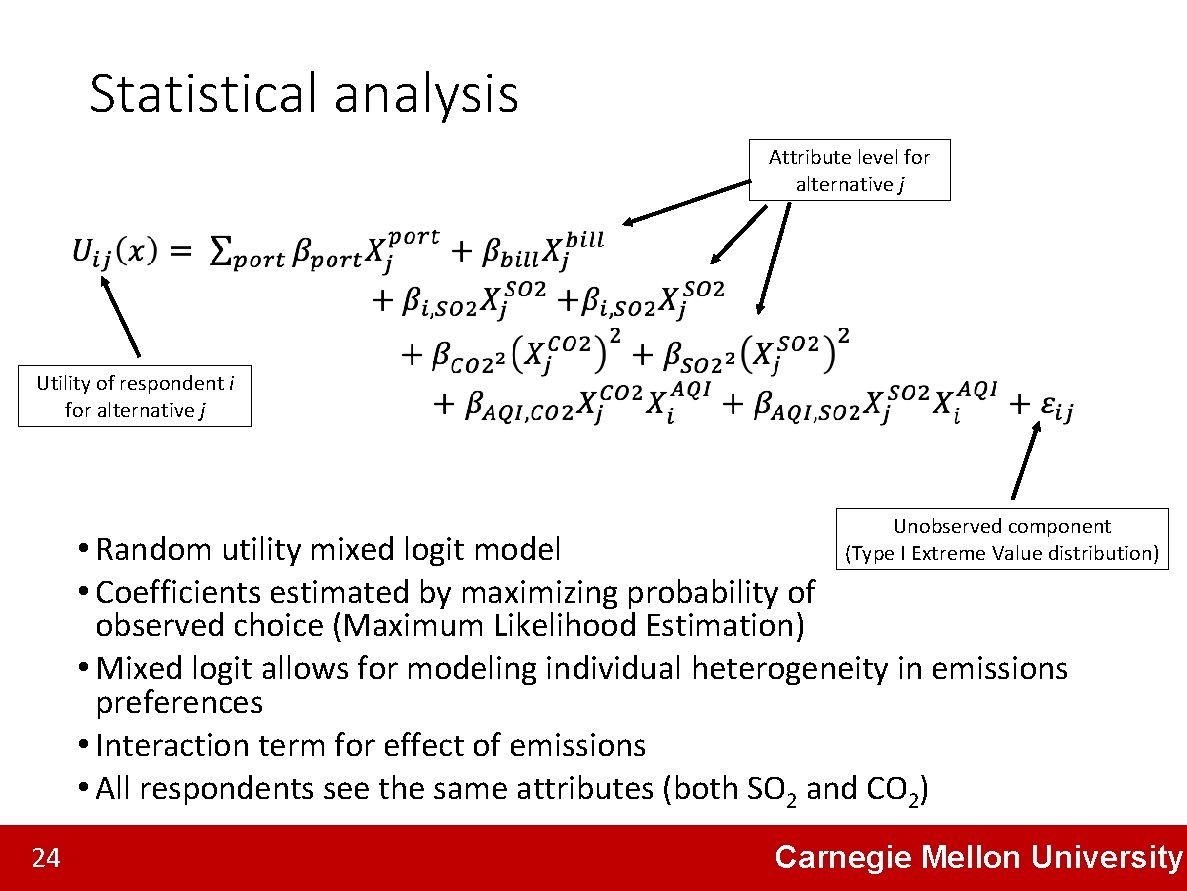

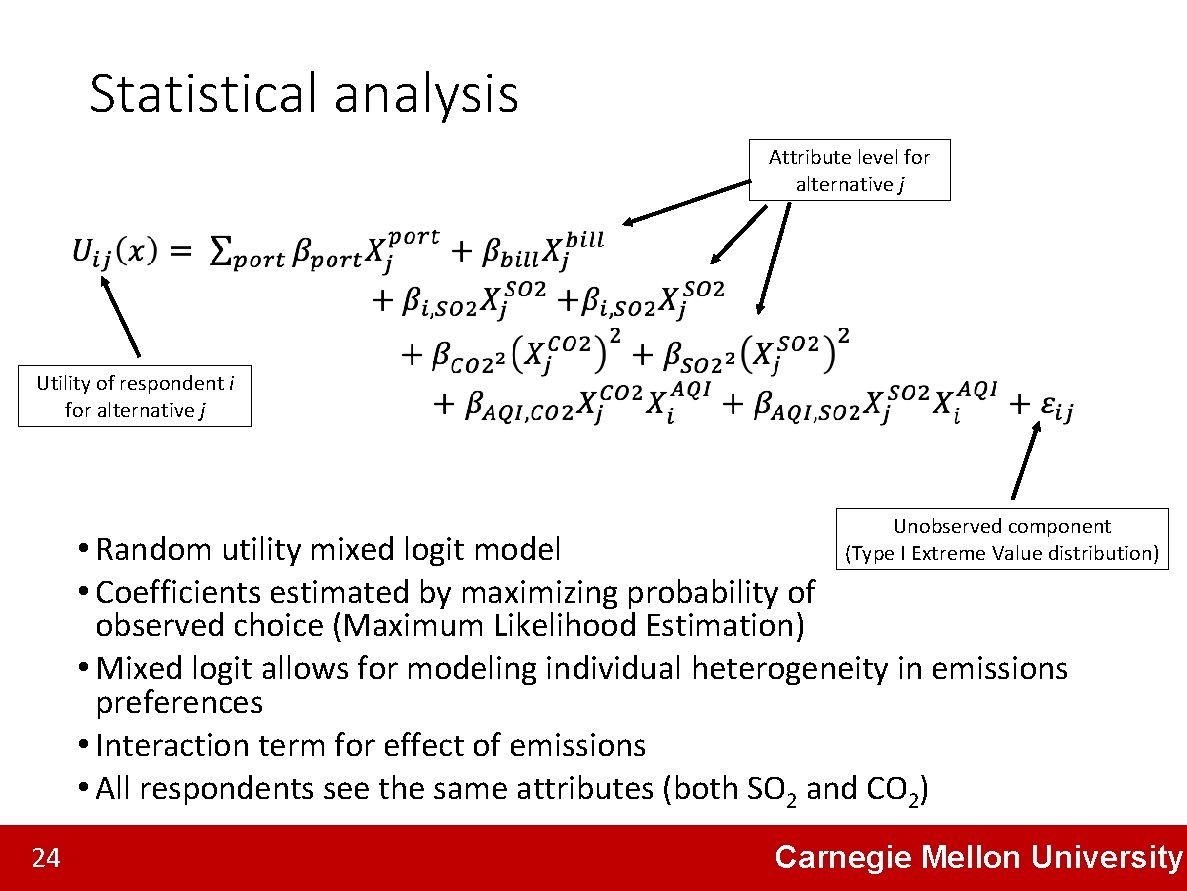

Statistical analysis Attribute level for alternative j Utility of respondent i for alternative j Unobserved component (Type I Extreme Value distribution) • Random utility mixed logit model • Coefficients estimated by maximizing probability of observed choice (Maximum Likelihood Estimation) • Mixed logit allows for modeling individual heterogeneity in emissions preferences • Interaction term for effect of emissions • All respondents see the same attributes (both SO 2 and CO 2) 24 Carnegie Mellon University

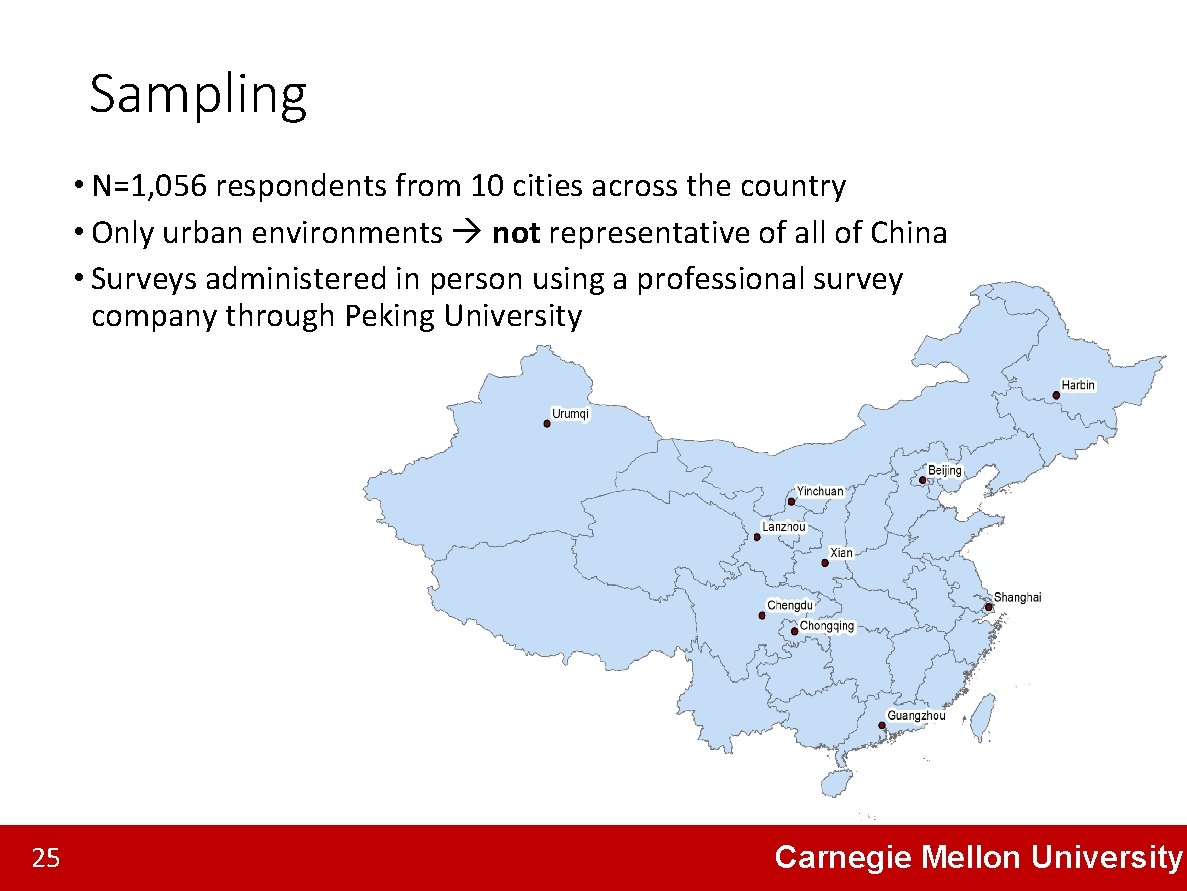

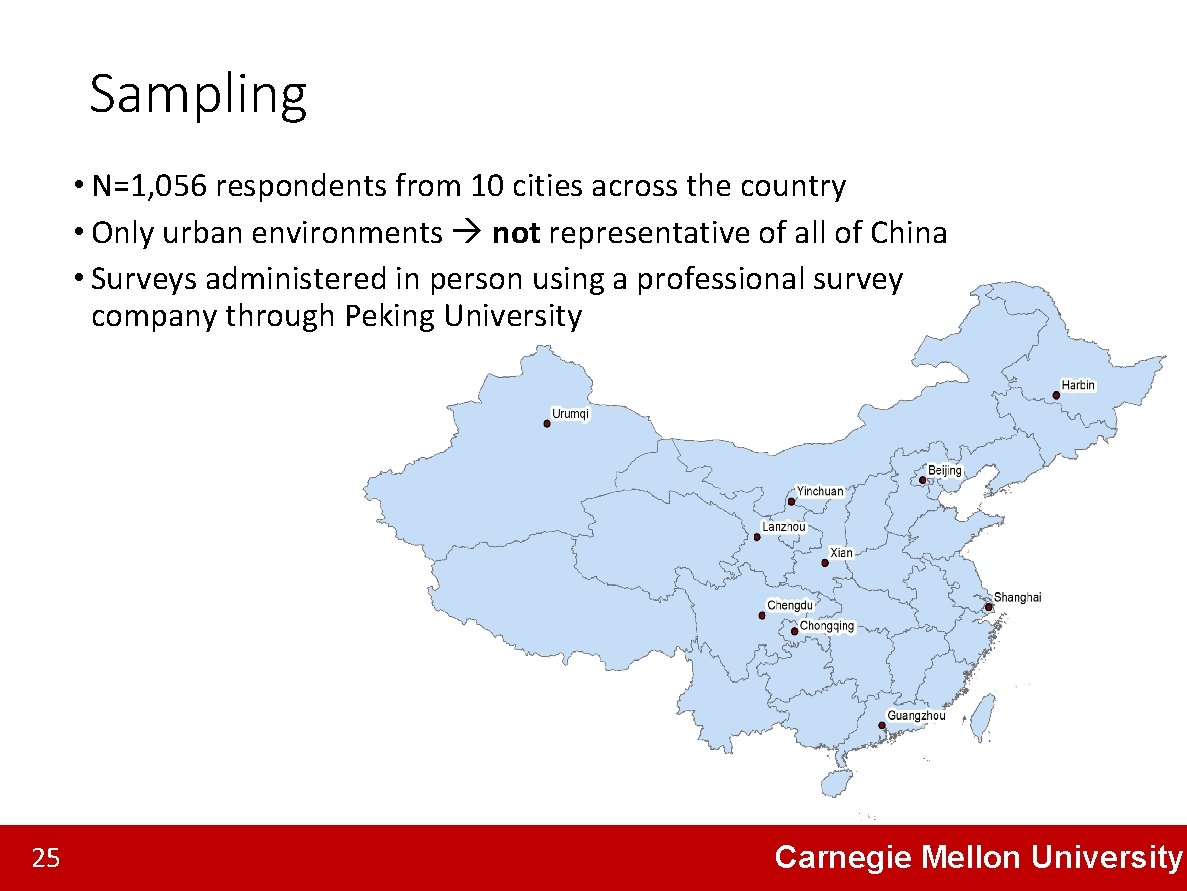

Sampling • N=1, 056 respondents from 10 cities across the country • Only urban environments not representative of all of China • Surveys administered in person using a professional survey company through Peking University 25 Carnegie Mellon University

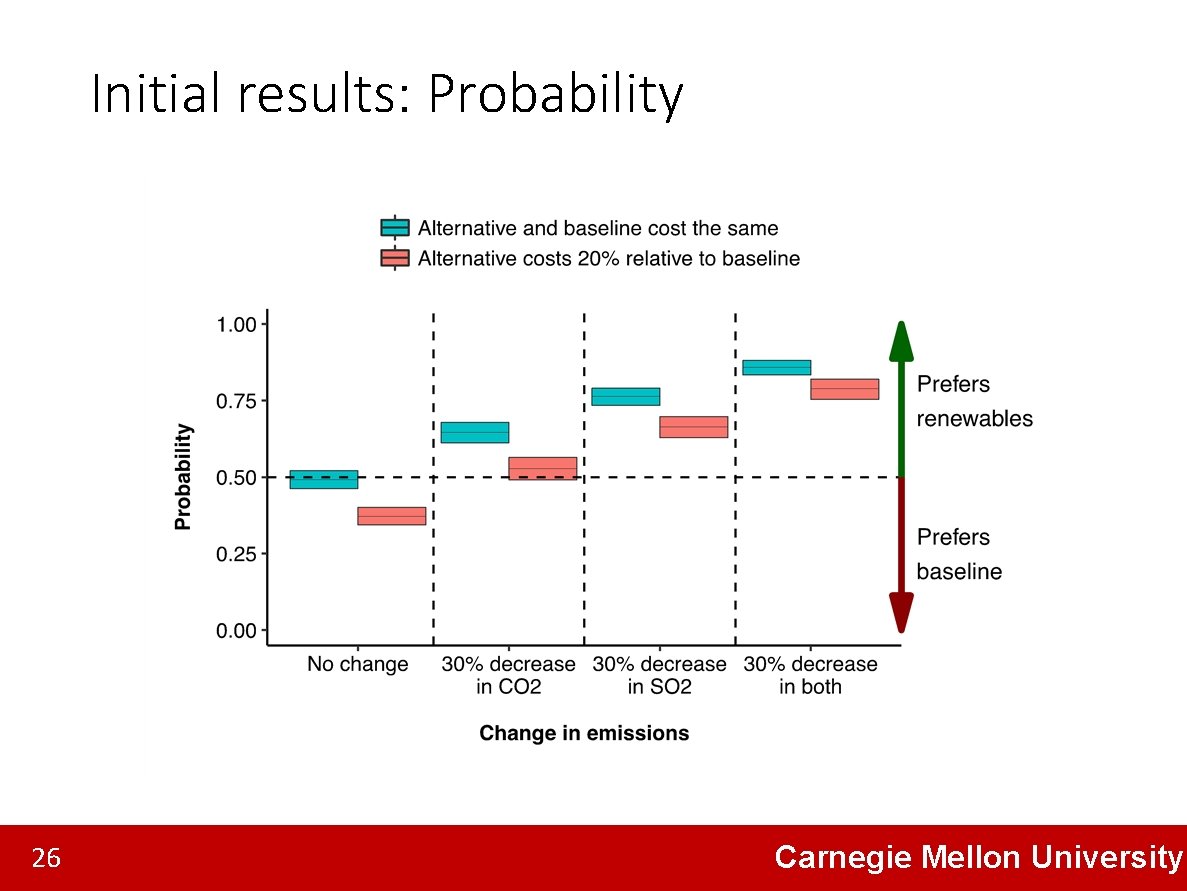

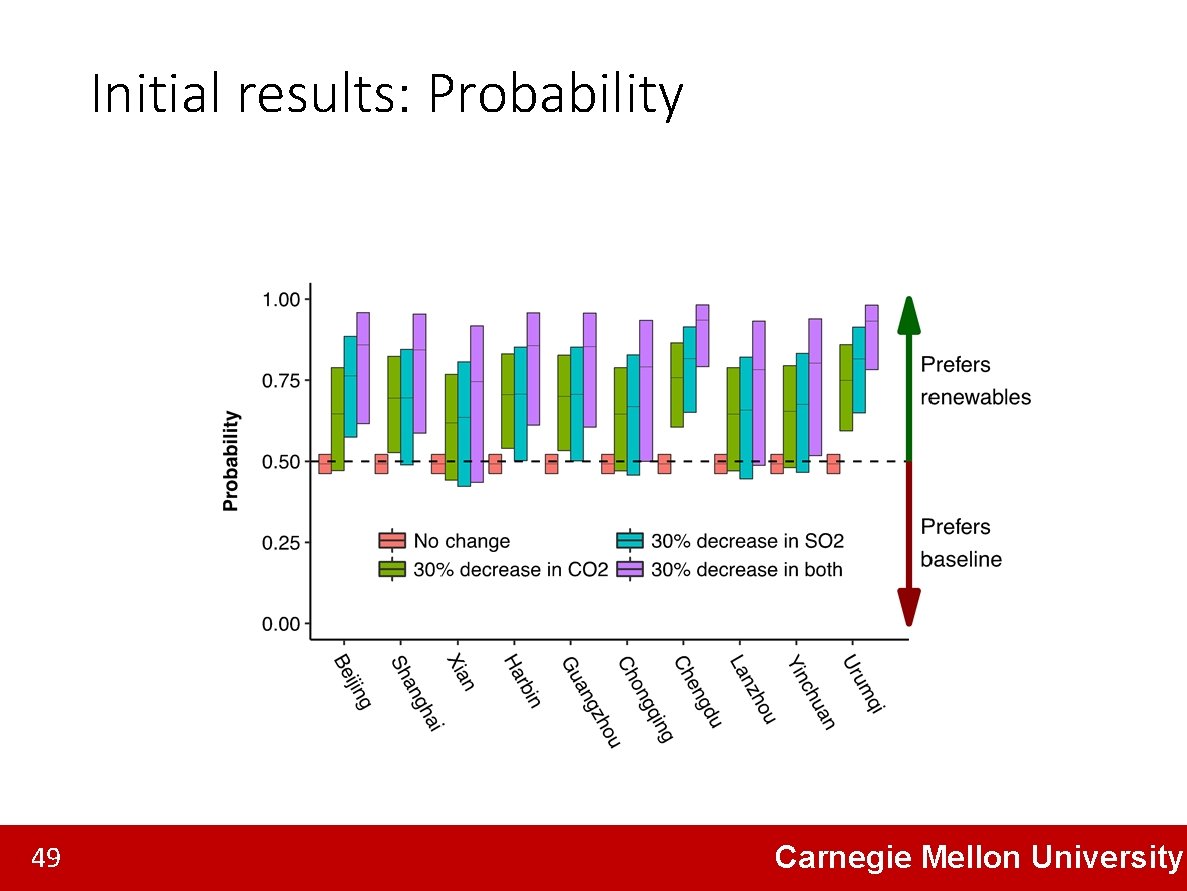

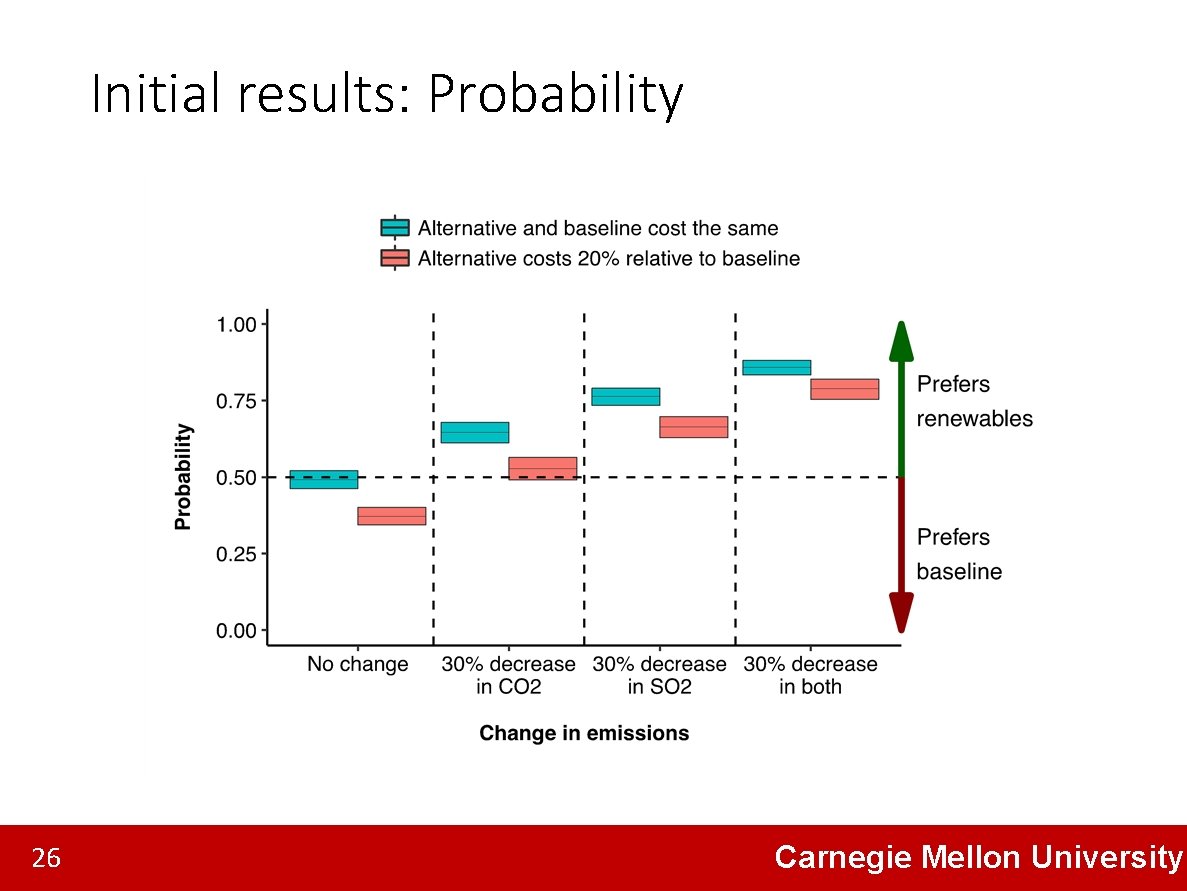

Initial results: Probability 26 Carnegie Mellon University

Initial results: Probability 27 Carnegie Mellon University

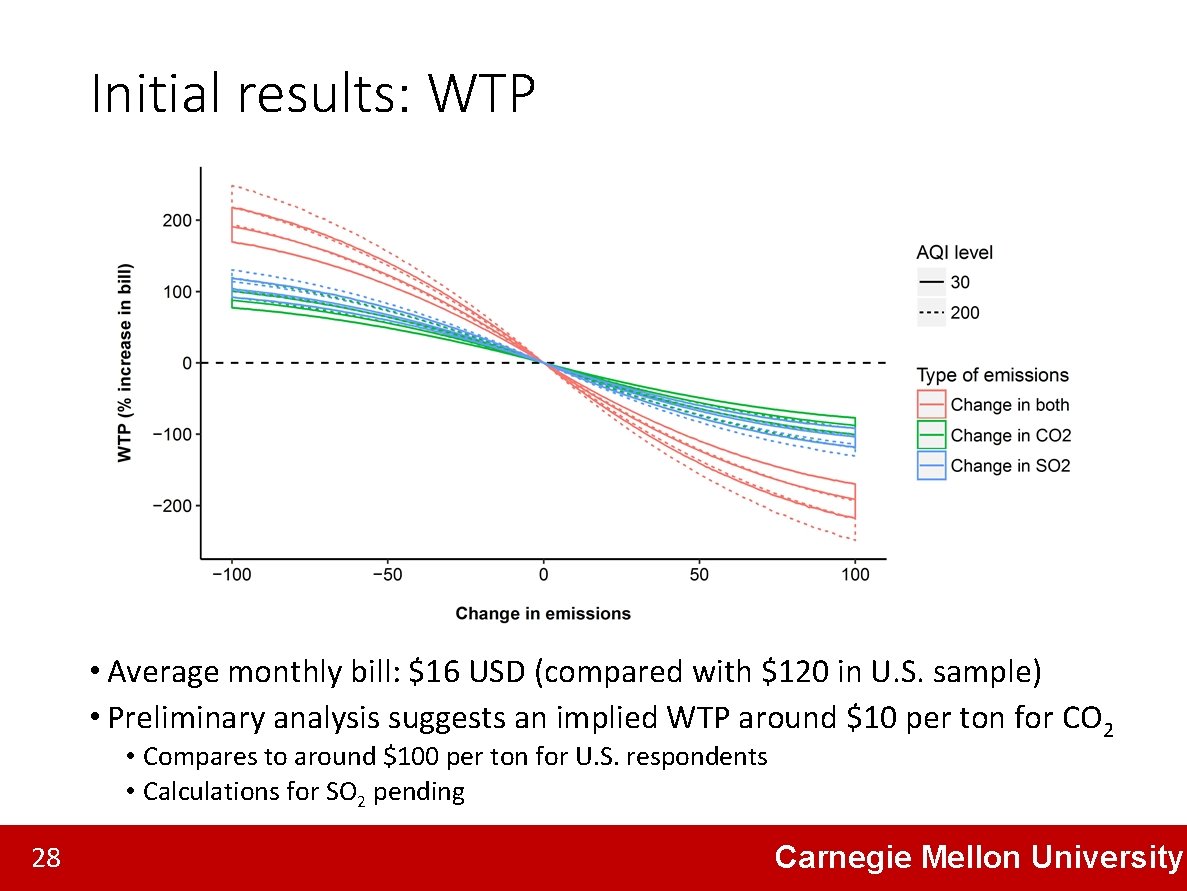

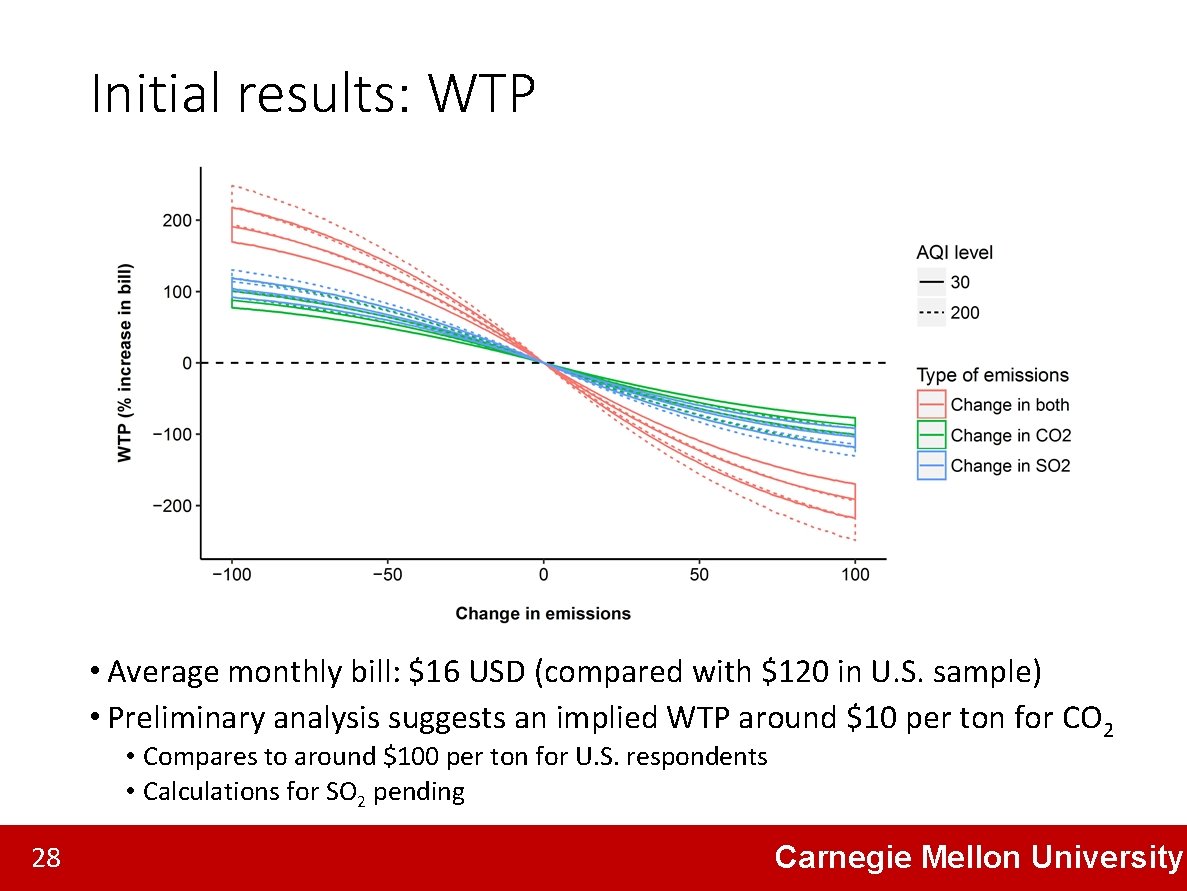

Initial results: WTP • Average monthly bill: $16 USD (compared with $120 in U. S. sample) • Preliminary analysis suggests an implied WTP around $10 per ton for CO 2 • Compares to around $100 per ton for U. S. respondents • Calculations for SO 2 pending 28 Carnegie Mellon University

Summary of findings – Study 2 • Improvements to both climate and health gain more support than one alone (same as U. S. study) • Less standalone support renewables (different from U. S. study) • Stronger support for cleaning up the air (different from U. S. study), but higher rate of diminishing returns for SO 2 than CO 2 • Lower absolute WTP in China relative to U. S. , but higher relative to current bill levels • Slightly stronger preferences for reducing either type of emissions on days with bad air quality 29 Carnegie Mellon University

Conclusions • Respondents across both surveys supportive of scenarios with emissions reductions (and state willingness to pay for those reductions) • Chinese respondents have stronger relative preferences for cleaning up the air compared to climate mitigation (and that effect seems to be driven by pollution levels) • Strengths of discrete choice method should be considered along with the limitations • Hypothetical choices, survey design can affect results (Louviere, 2006) • Cognitive biases in stated preference studies (Fischhoff, 2005) • Some evidence for construct and convergent validity (Vossler et. al. , 2016), but careful design required to minimize bias 30 Carnegie Mellon University

Policy implications • Technology neutral policies for emissions reductions (from a broad planning perspective) • Communicate information on emissions reductions, particularly health information when trying to advance climate mitigation strategies • Consider co-optimizing climate mitigation policies across multiple health and climate objectives to gain additional support • Both countries can gain more support for climate mitigation by connecting it to air pollution (particularly true for China) 31 Carnegie Mellon University

Acknowledgements • NSF Center for Climate and Energy Decision Making (NSF SES-0949710 and SES-1463492) • Steinbrenner Institute for Environmental Education and Research • NSF East Asia and Pacific Summer Institutes (EAPSI) Program • China Science and Technology Exchange Center (CSTEC) • Department of Environmental Management, Peking University • Center for Air, Climate and Energy Solutions • Contact: bsergi@andrew. cmu. edu 32 Carnegie Mellon University

BACKUP SLIDES 33 Carnegie Mellon University

Pros and cons of discrete choice methods • Strengths • More closely simulates a choice environment • Tailored to measuring marginal effects/tradeoffs • Researcher able to control choice scenarios and information presented • Few alternatives for evaluating preferences for public goods not available in markets • Limitations • Hypothetical choices, survey design can affect results (Louviere, 2006) • Subject to same cognitive biases of stated preference studies (Fischhoff, 2005) • More cognitively demanding for respondents 34 Carnegie Mellon University

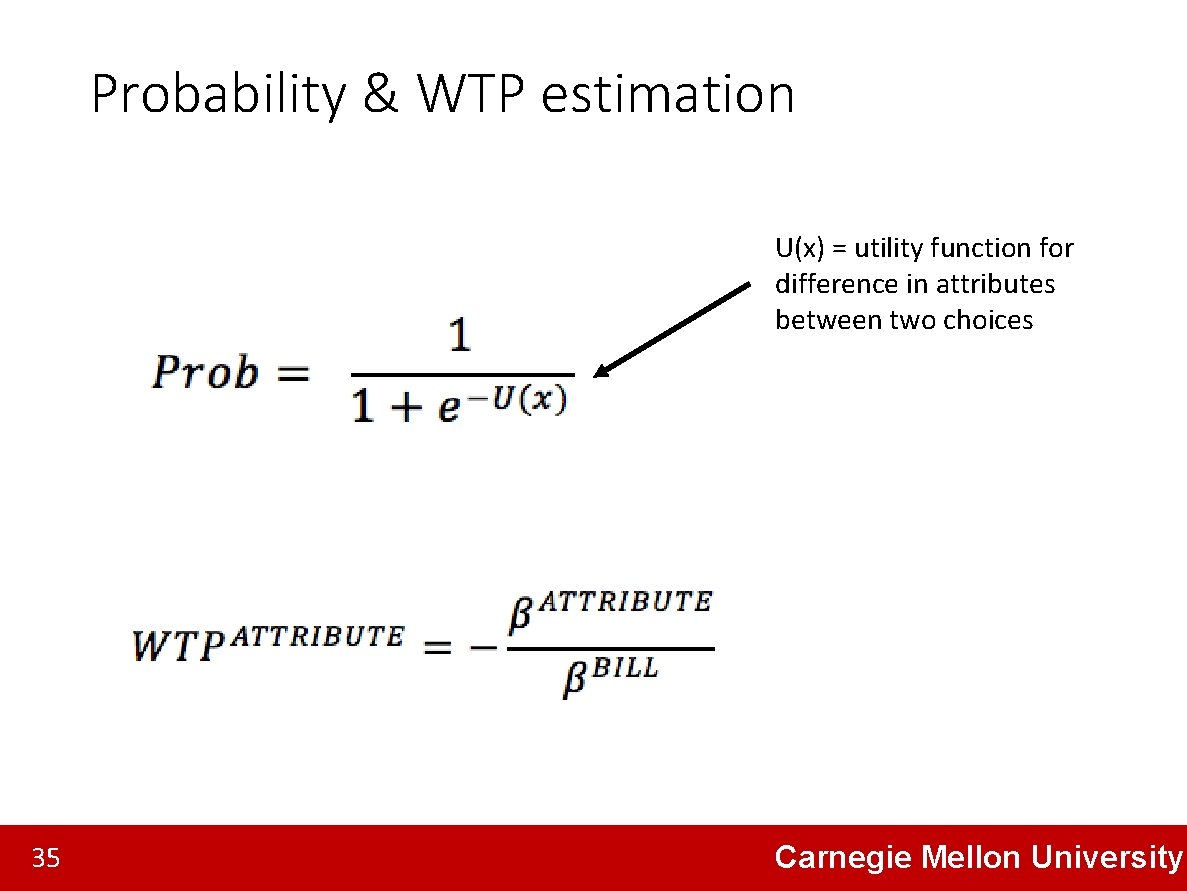

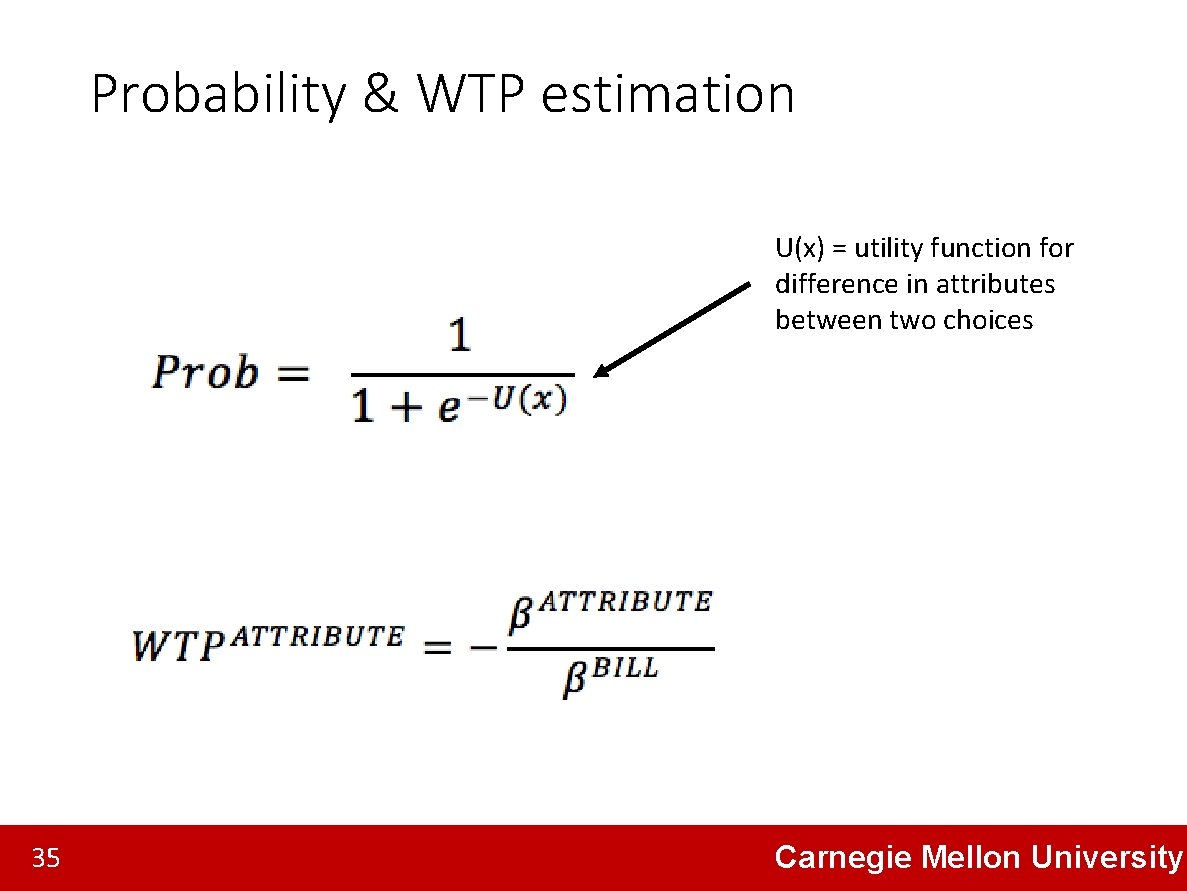

Probability & WTP estimation U(x) = utility function for difference in attributes between two choices 35 Carnegie Mellon University

STUDY 1 36 Carnegie Mellon University

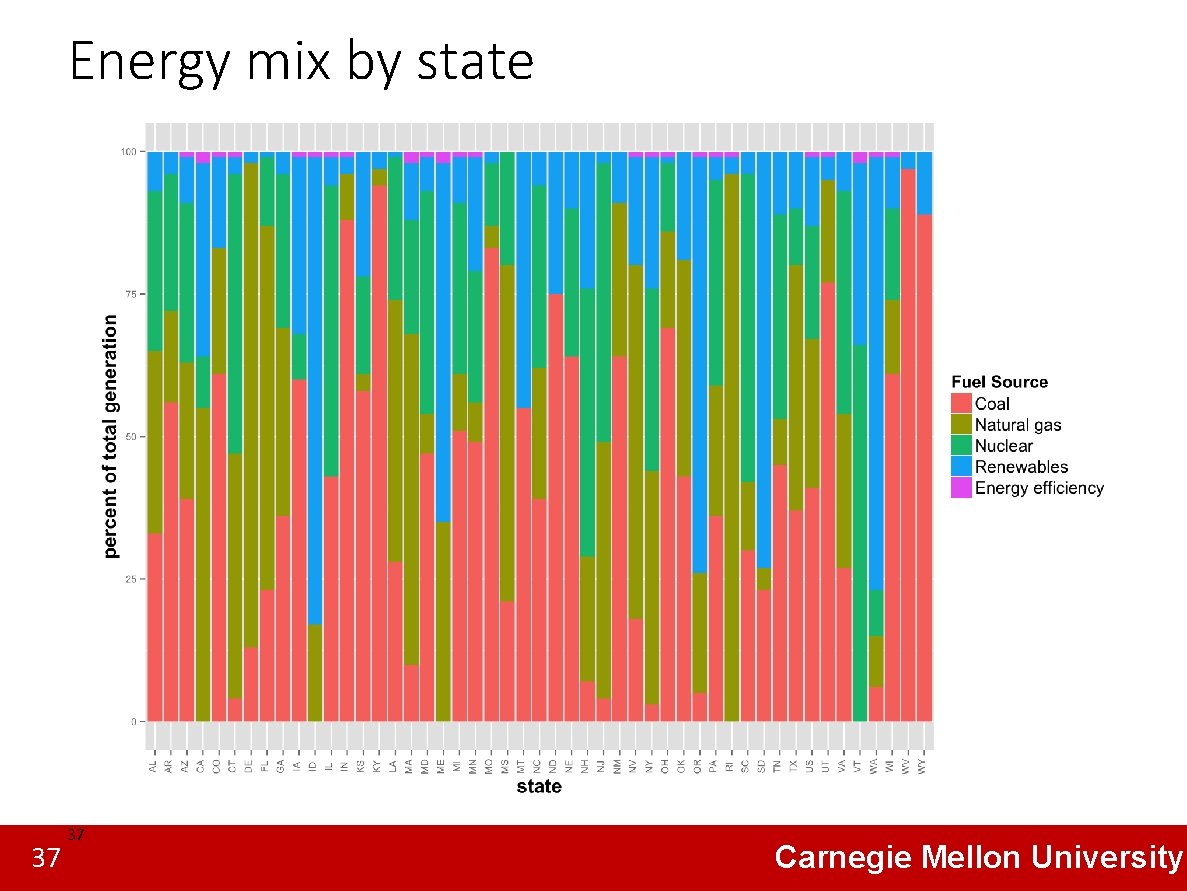

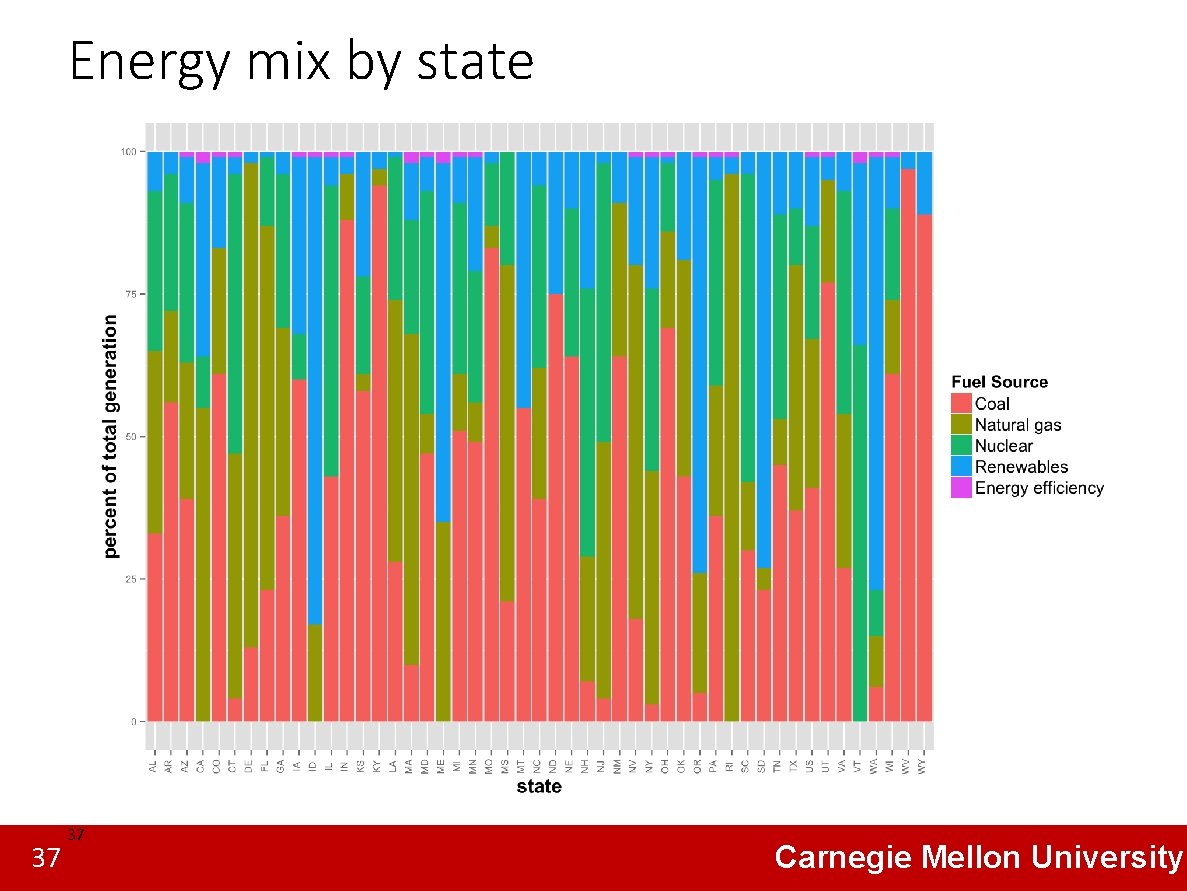

Energy mix by state 37 37 Carnegie Mellon University

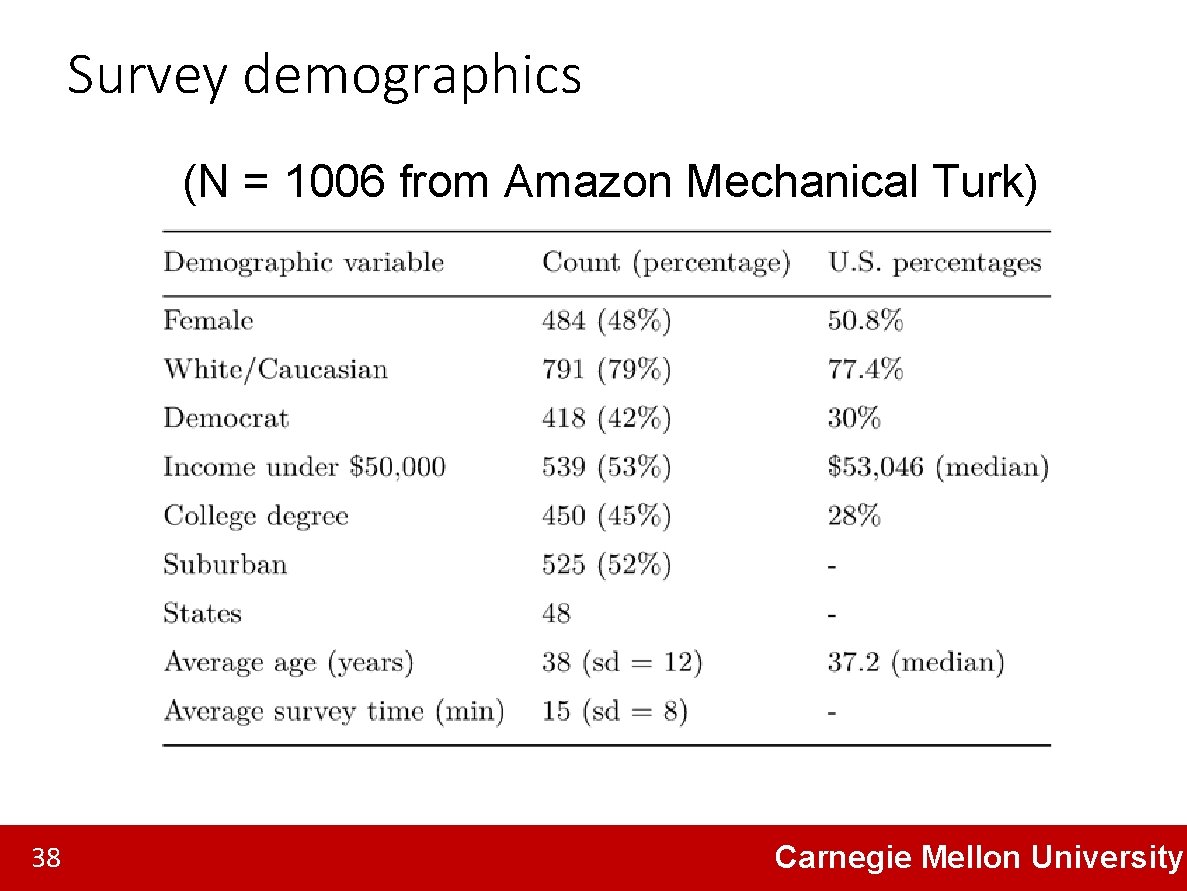

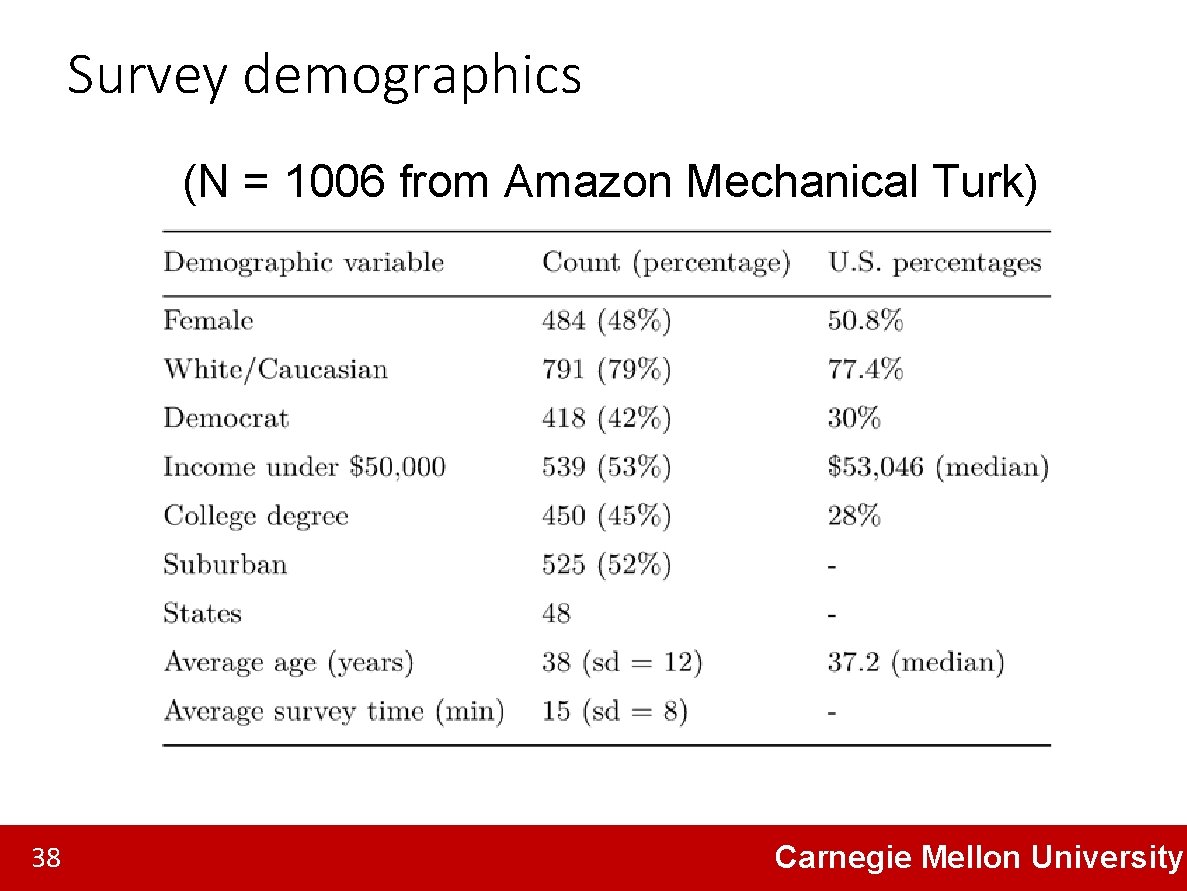

Survey demographics (N = 1006 from Amazon Mechanical Turk) 38 Carnegie Mellon University

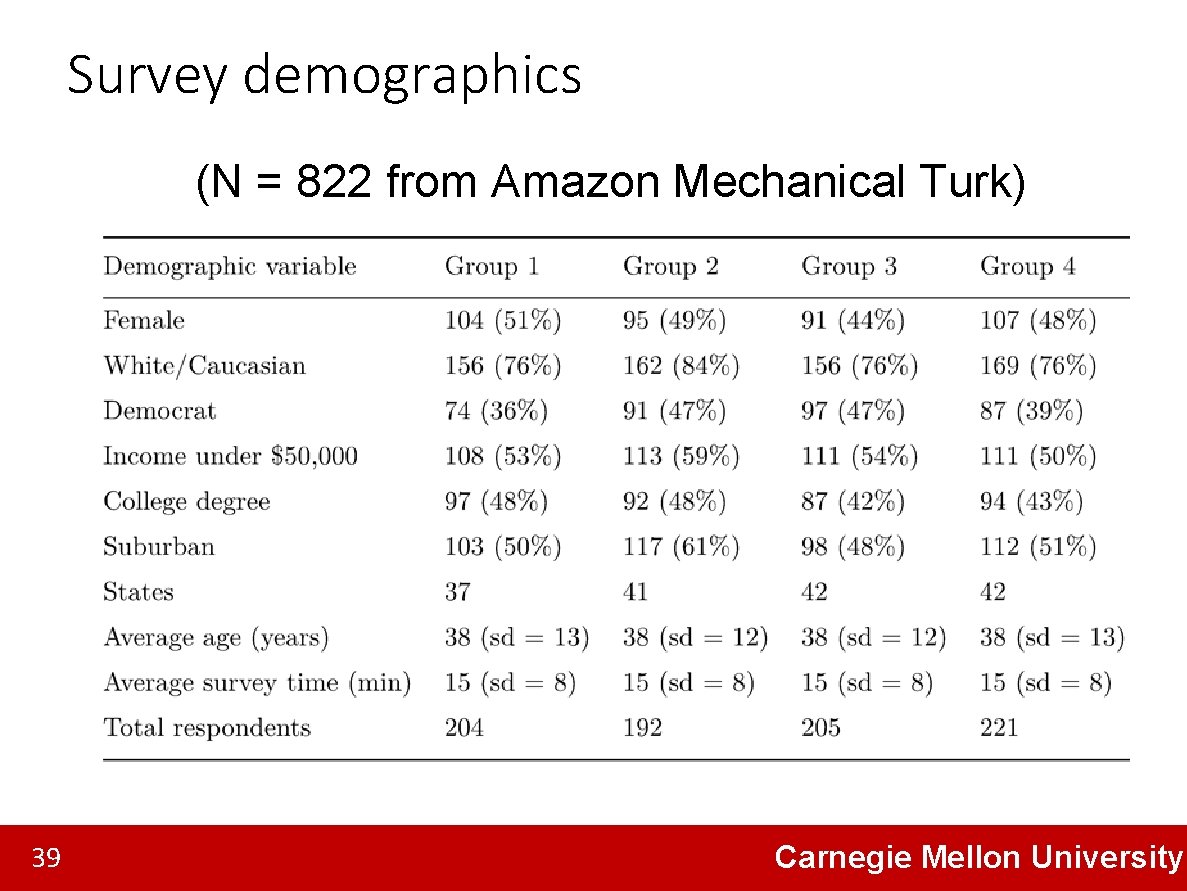

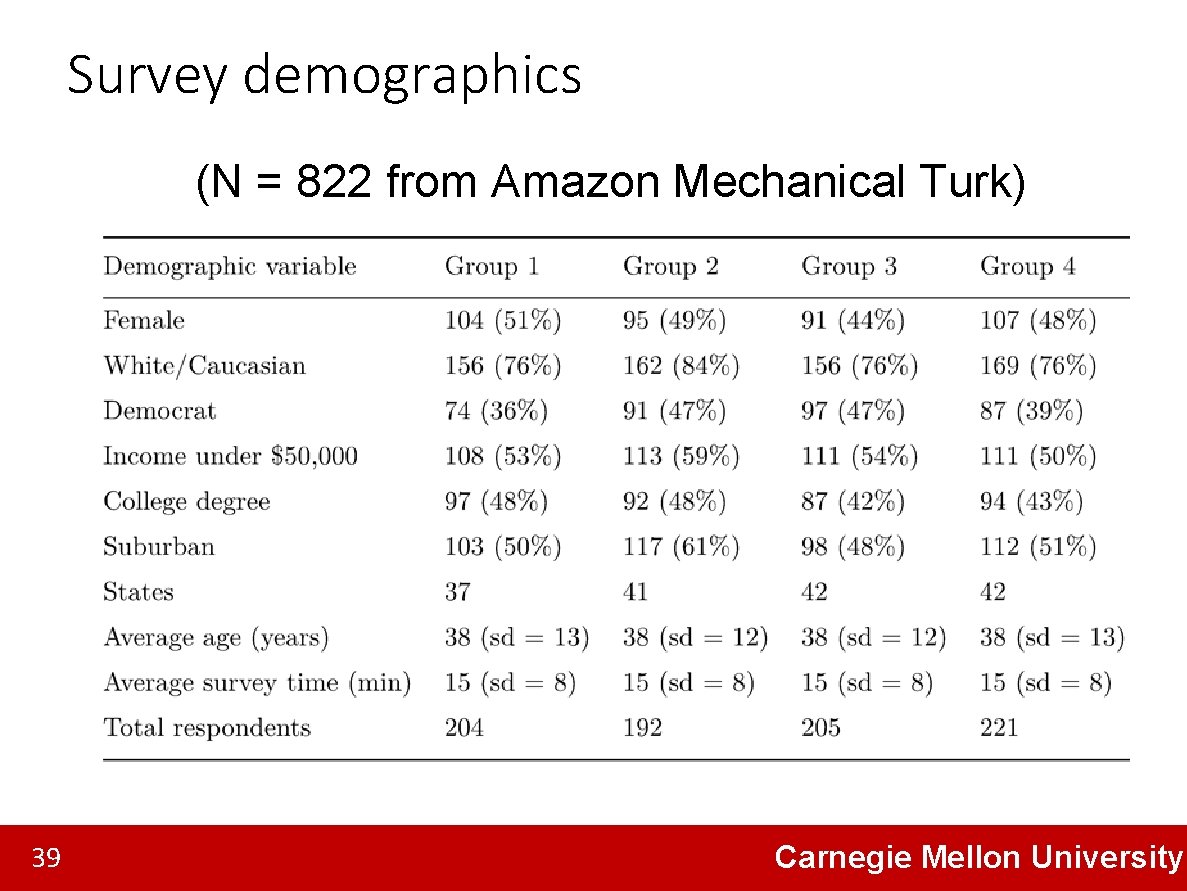

Survey demographics (N = 822 from Amazon Mechanical Turk) 39 Carnegie Mellon University

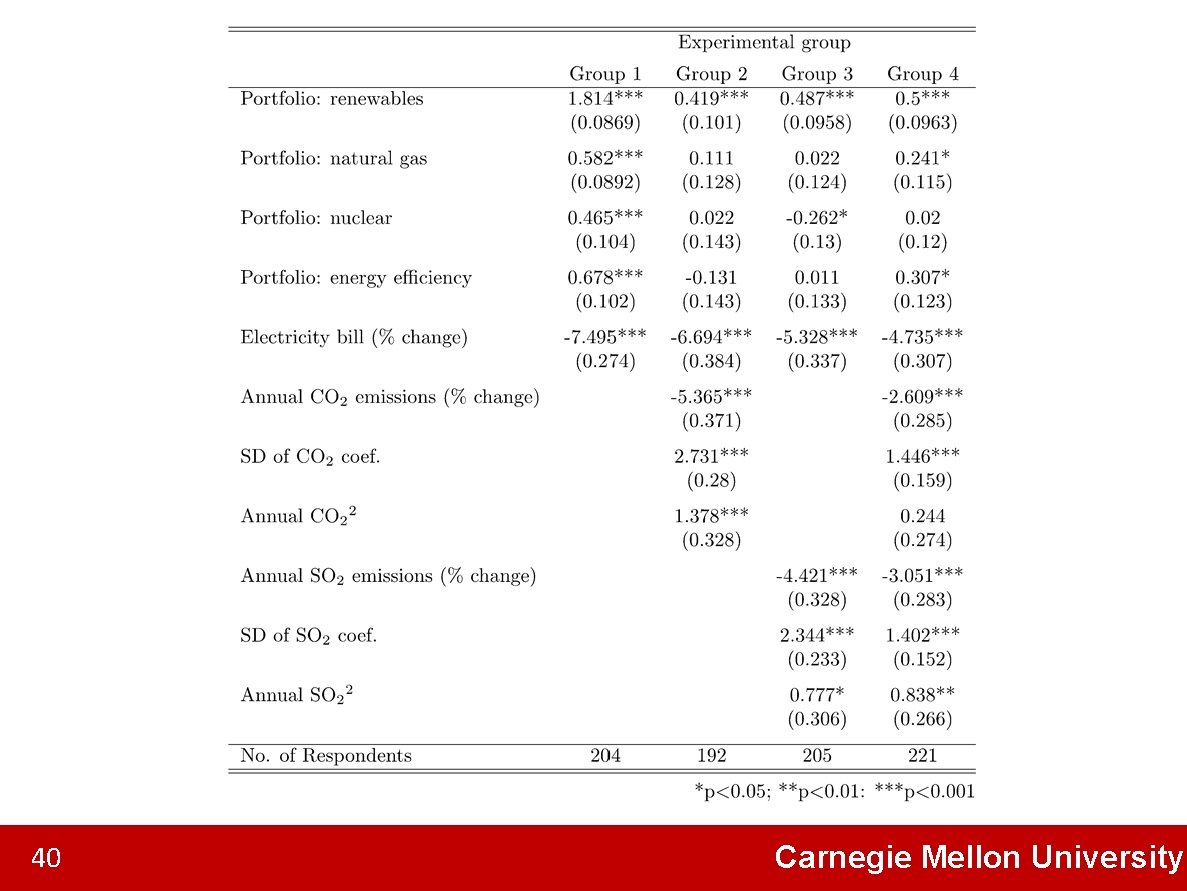

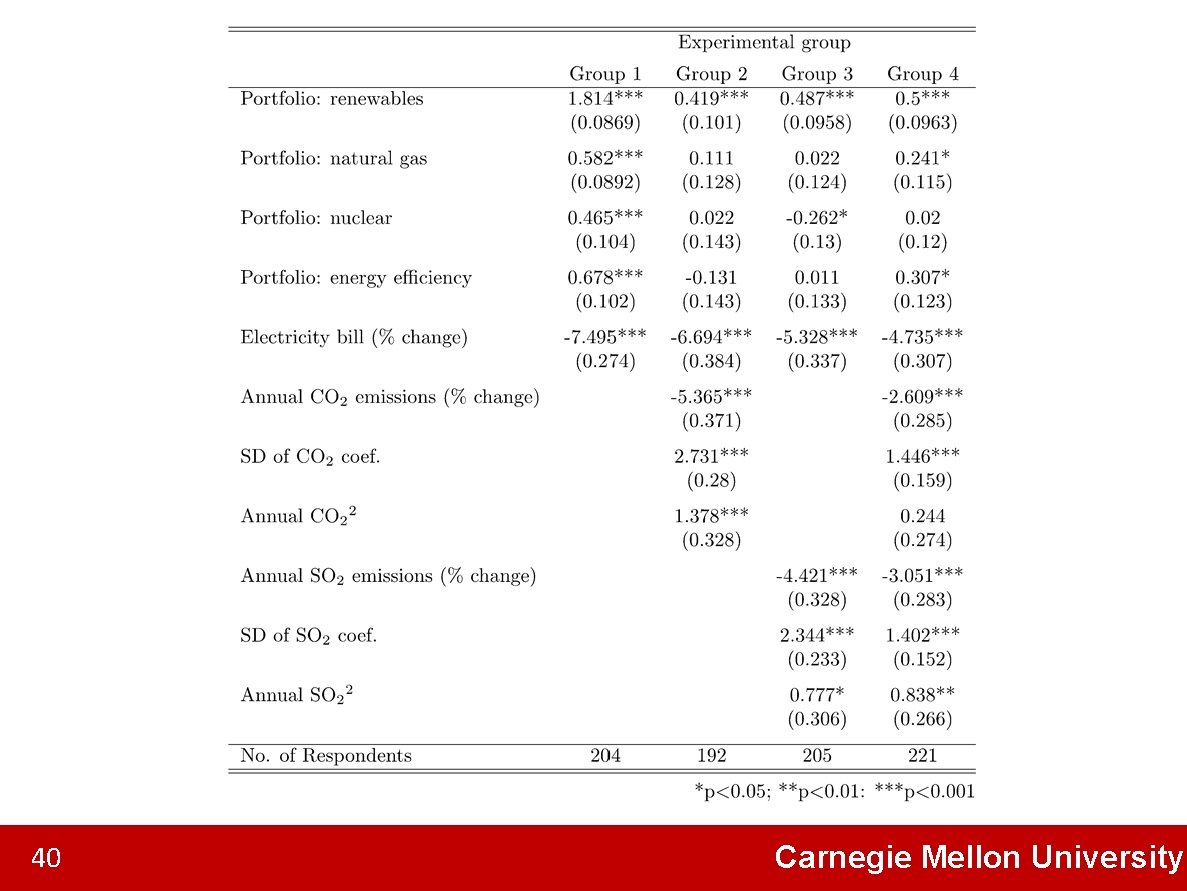

40 Carnegie Mellon University

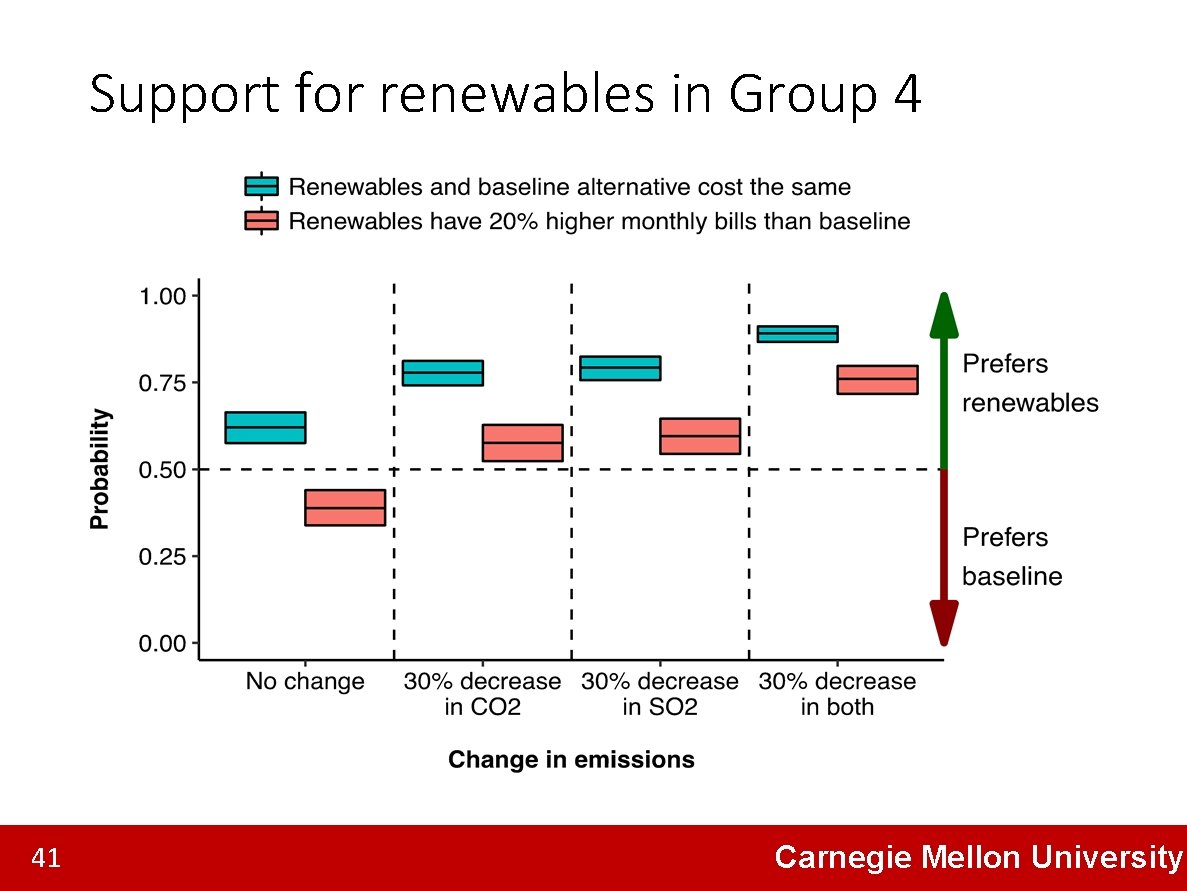

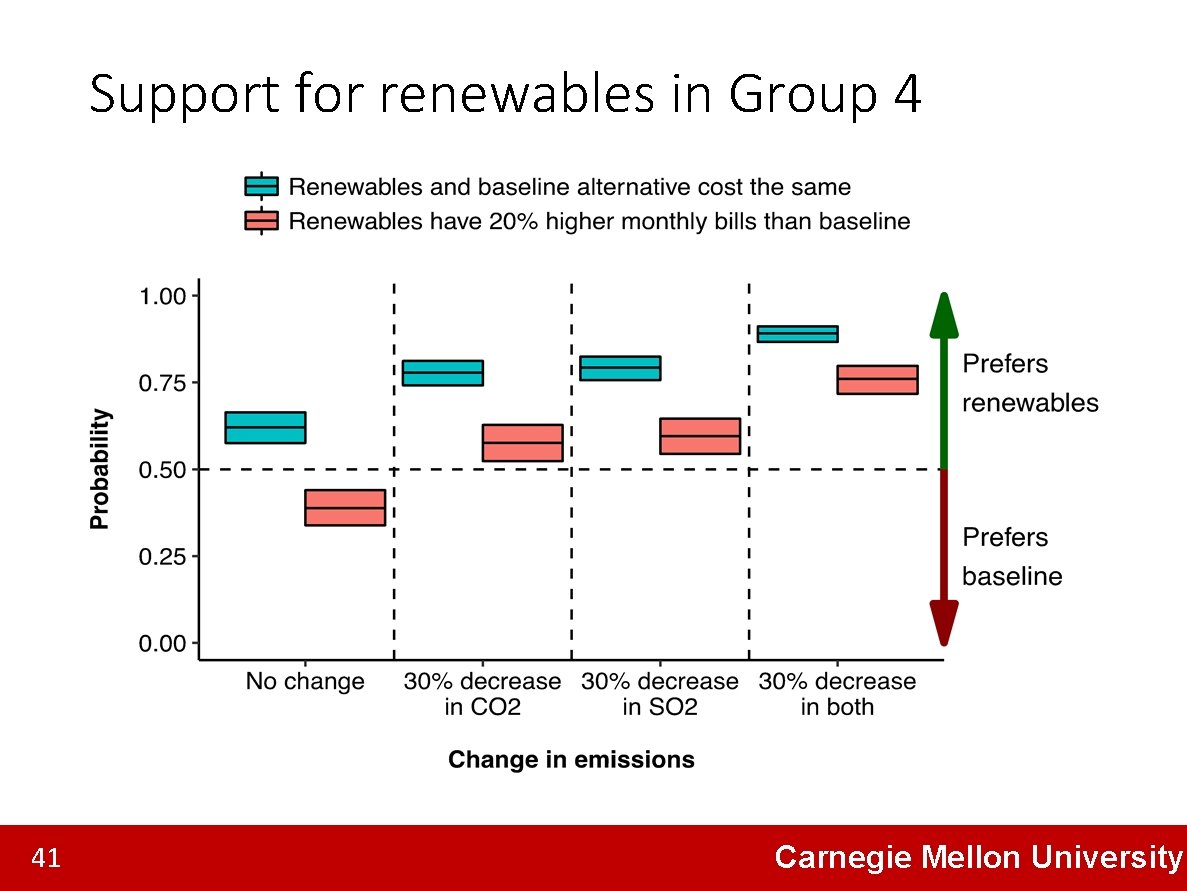

Support for renewables in Group 4 41 Carnegie Mellon University

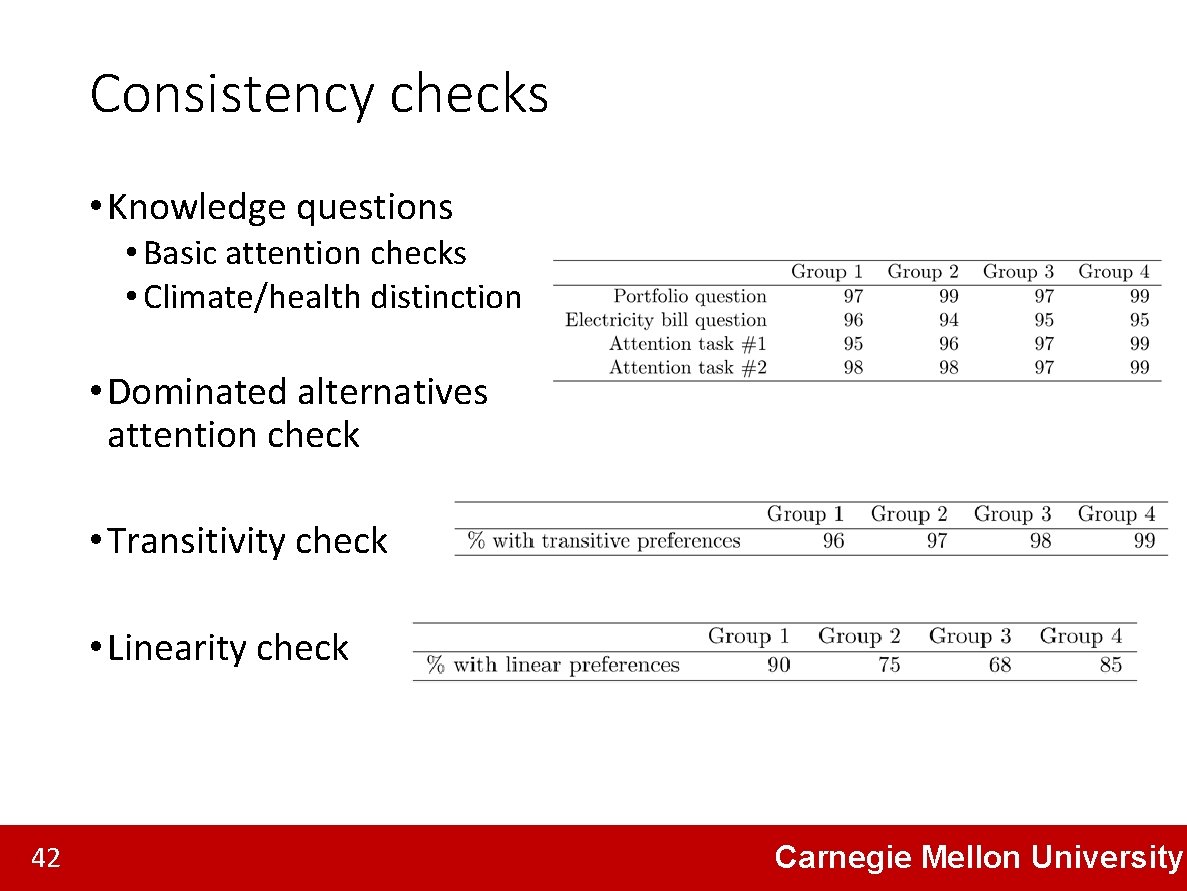

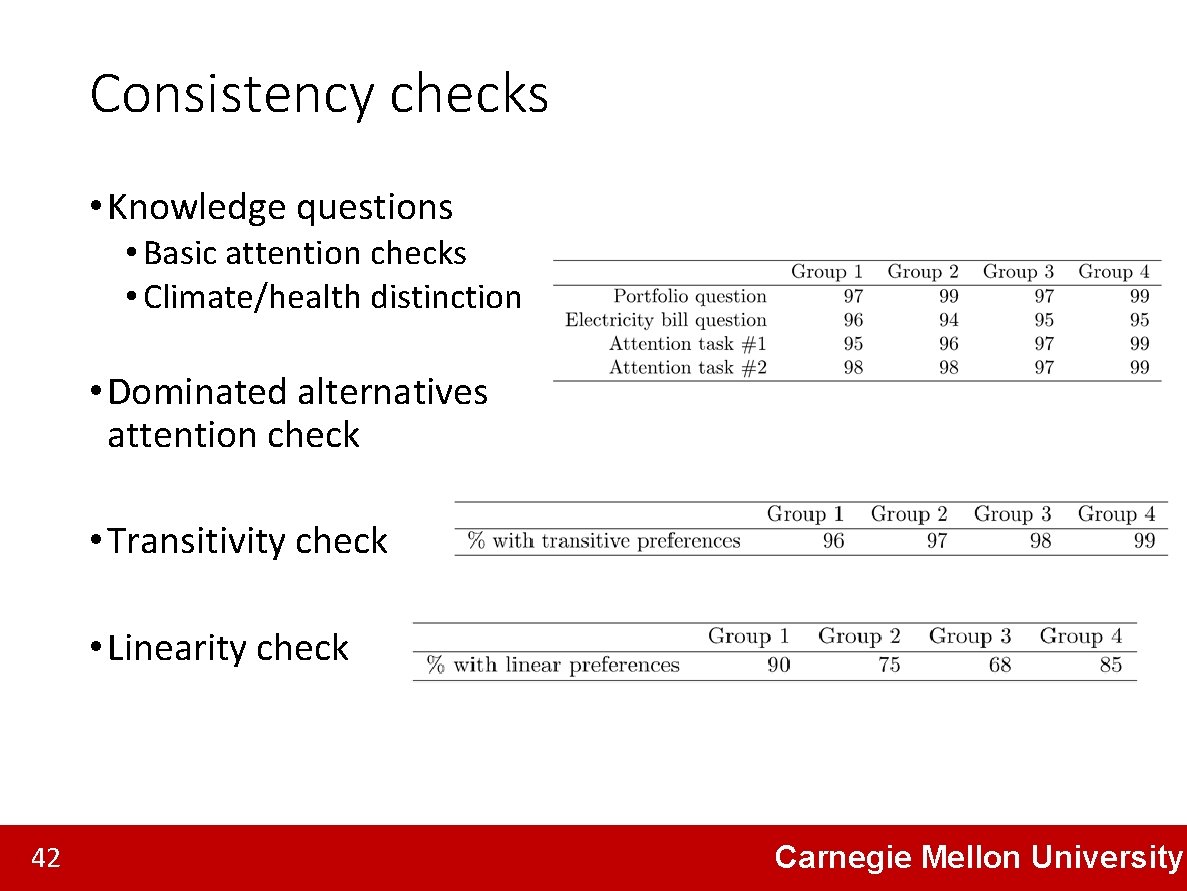

Consistency checks • Knowledge questions • Basic attention checks • Climate/health distinction • Dominated alternatives attention check • Transitivity check • Linearity check 42 Carnegie Mellon University

Convergent validity • Attribute ratings • Importance of climate change / air pollution • Stated willingness to pay 43 Carnegie Mellon University

STUDY 2 44 Carnegie Mellon University

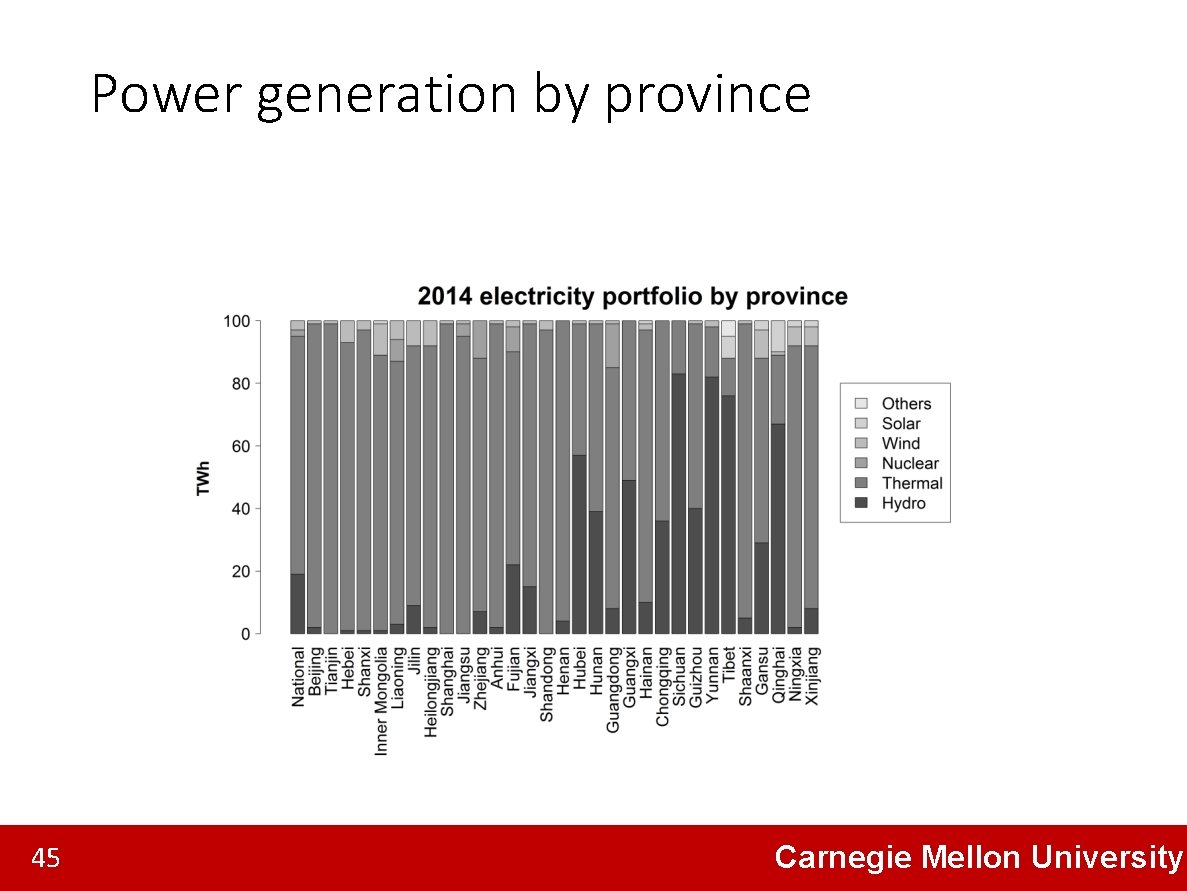

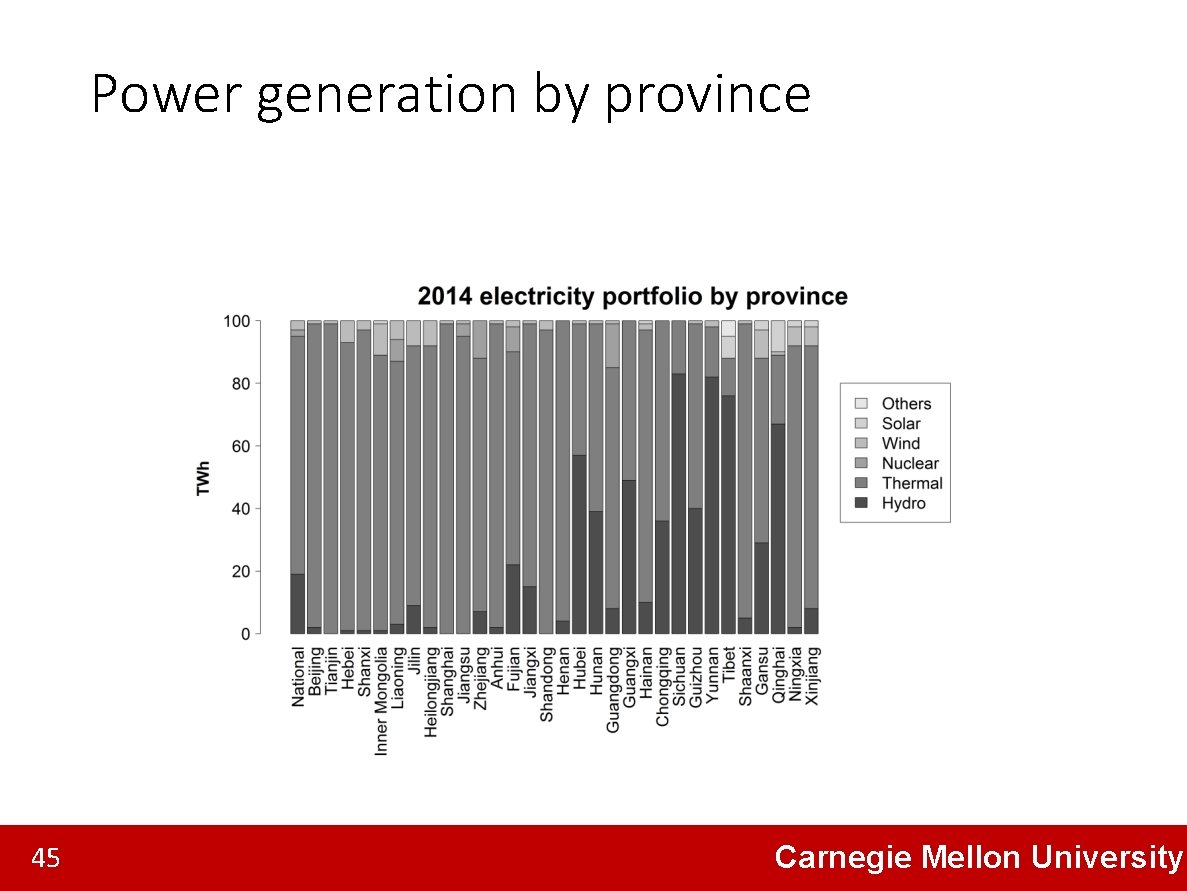

Power generation by province 45 Carnegie Mellon University

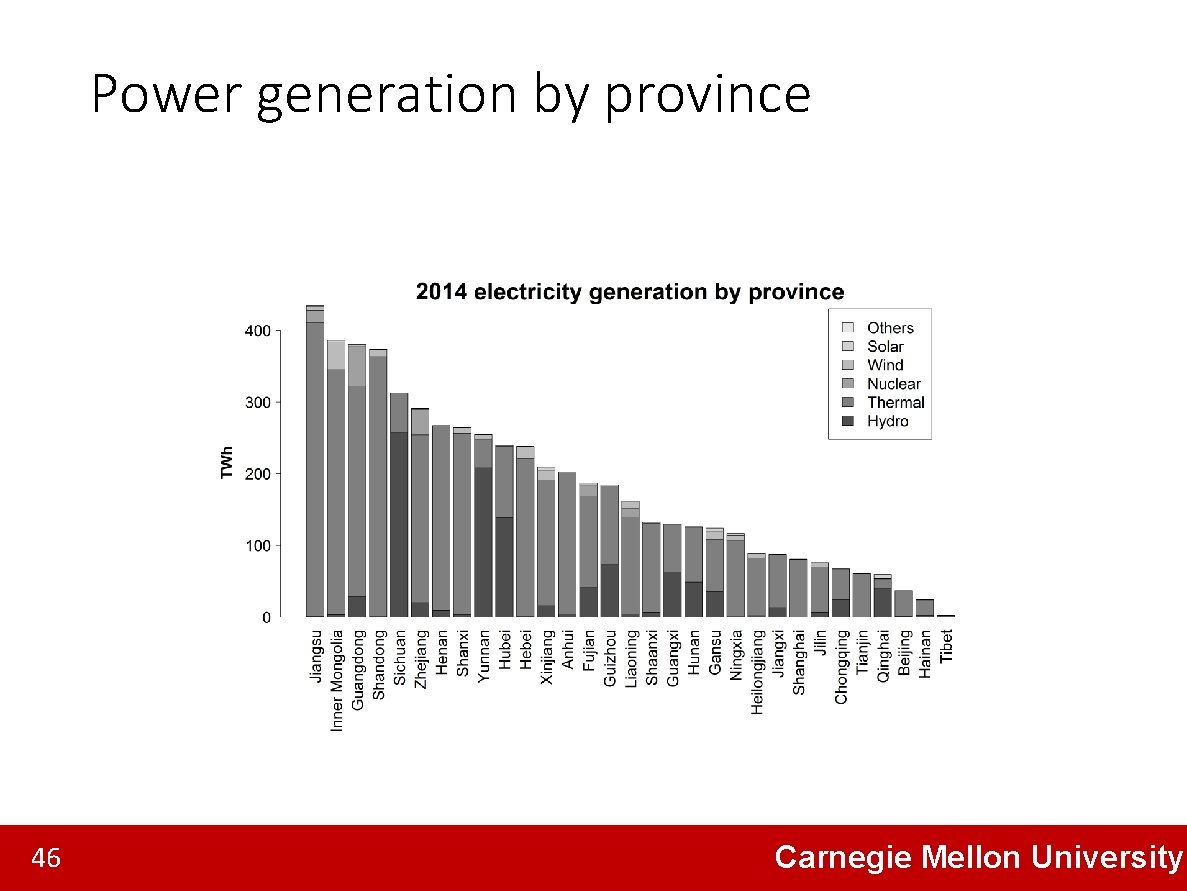

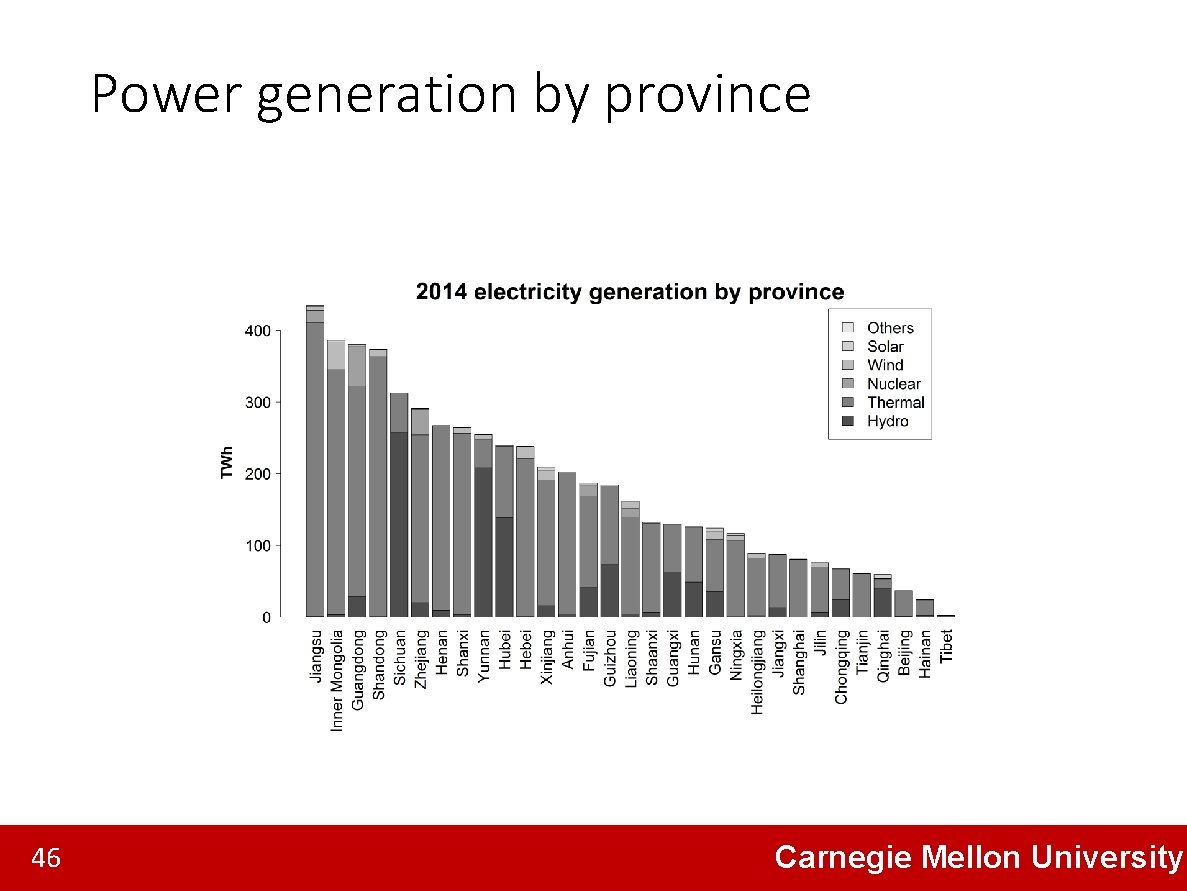

Power generation by province 46 Carnegie Mellon University

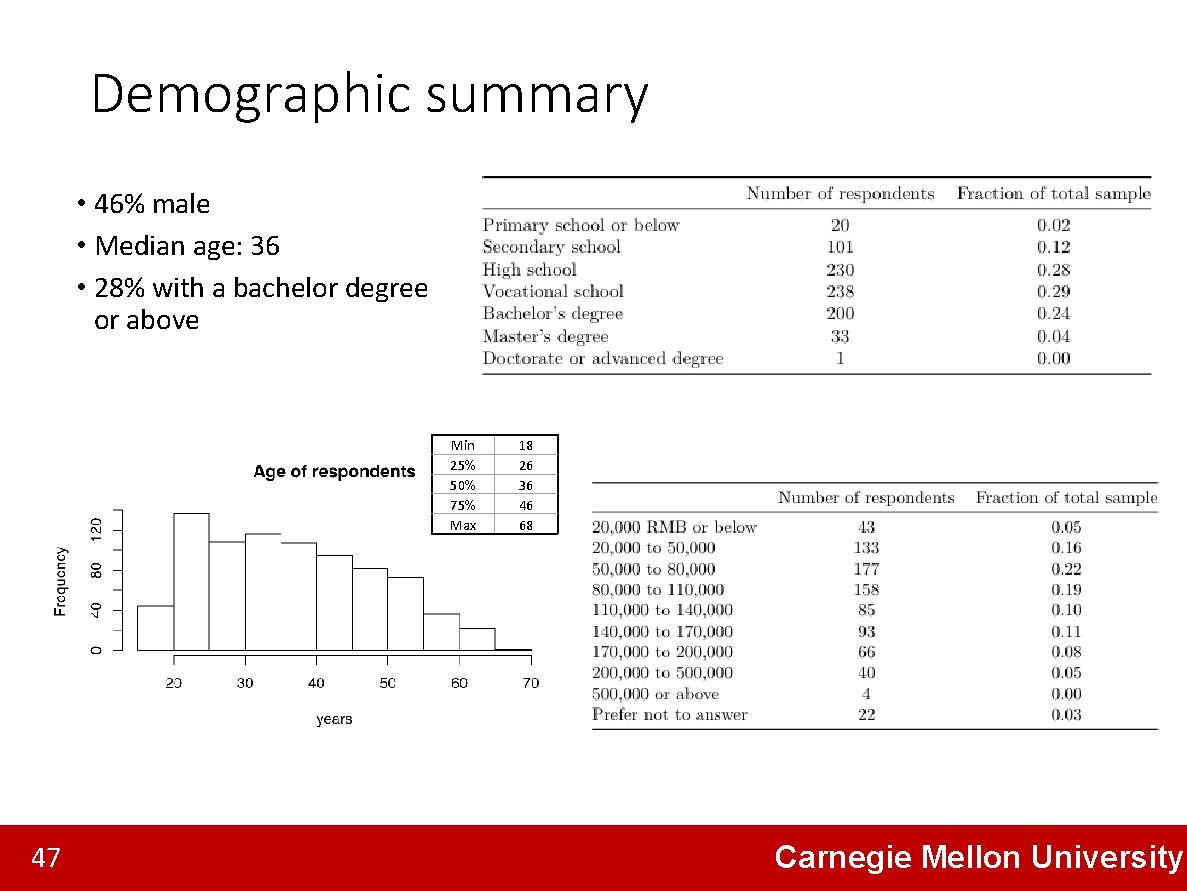

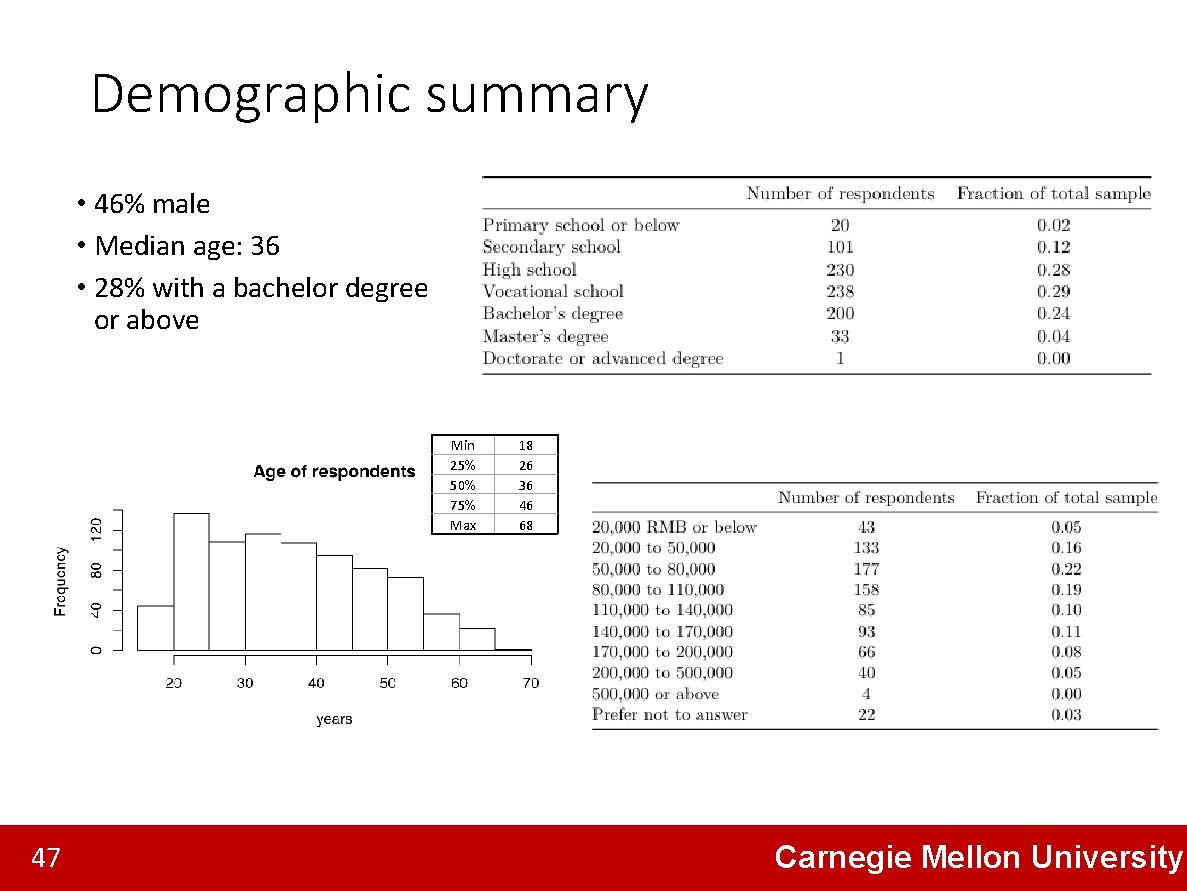

Demographic summary • 46% male • Median age: 36 • 28% with a bachelor degree or above Min 25% 50% 75% Max 47 18 26 36 46 68 Carnegie Mellon University

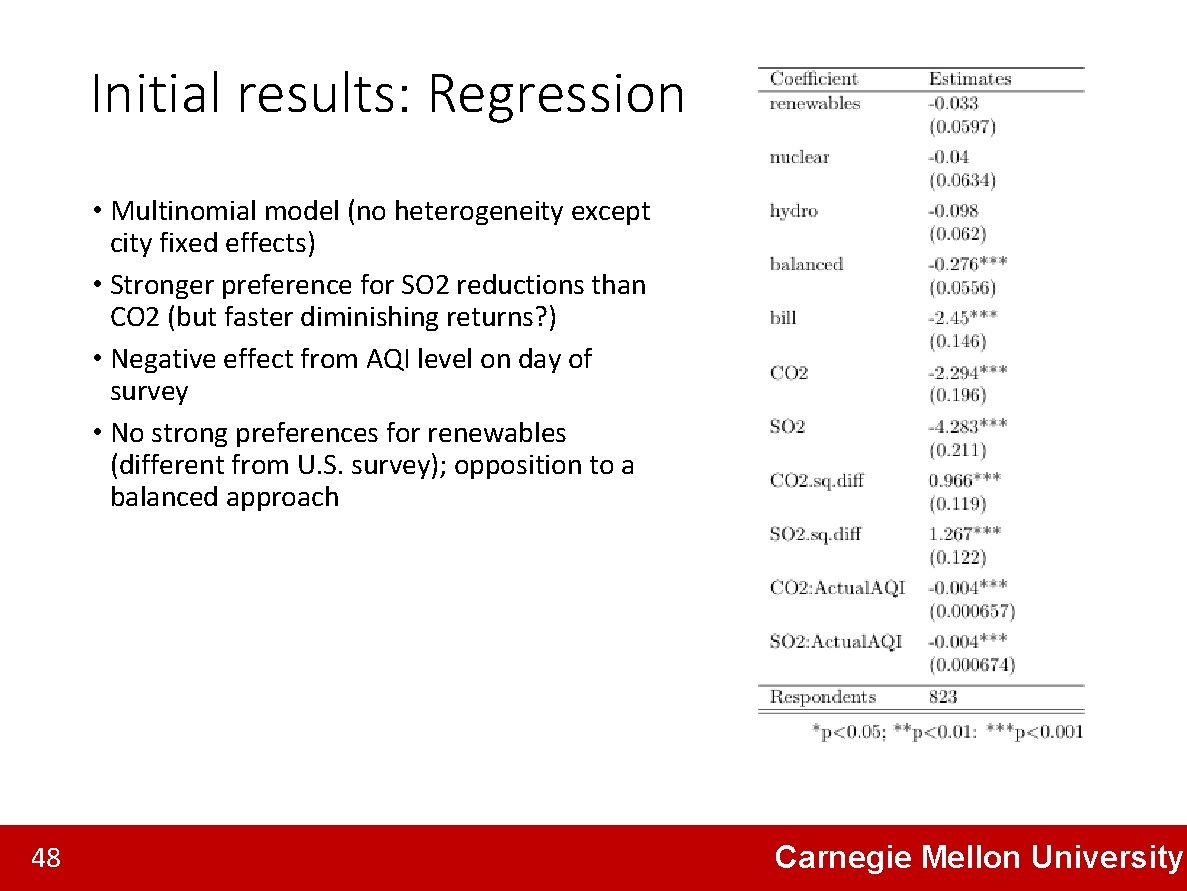

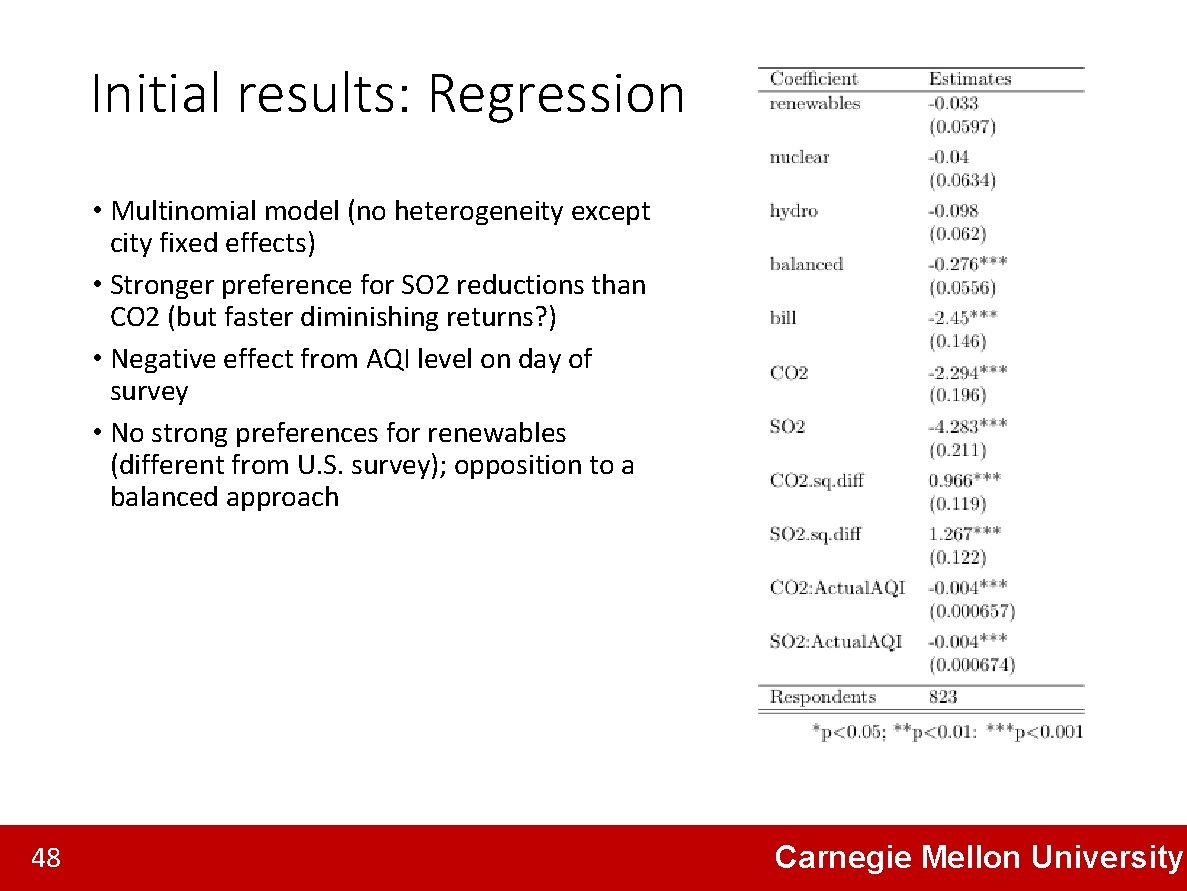

Initial results: Regression • Multinomial model (no heterogeneity except city fixed effects) • Stronger preference for SO 2 reductions than CO 2 (but faster diminishing returns? ) • Negative effect from AQI level on day of survey • No strong preferences for renewables (different from U. S. survey); opposition to a balanced approach 48 Carnegie Mellon University

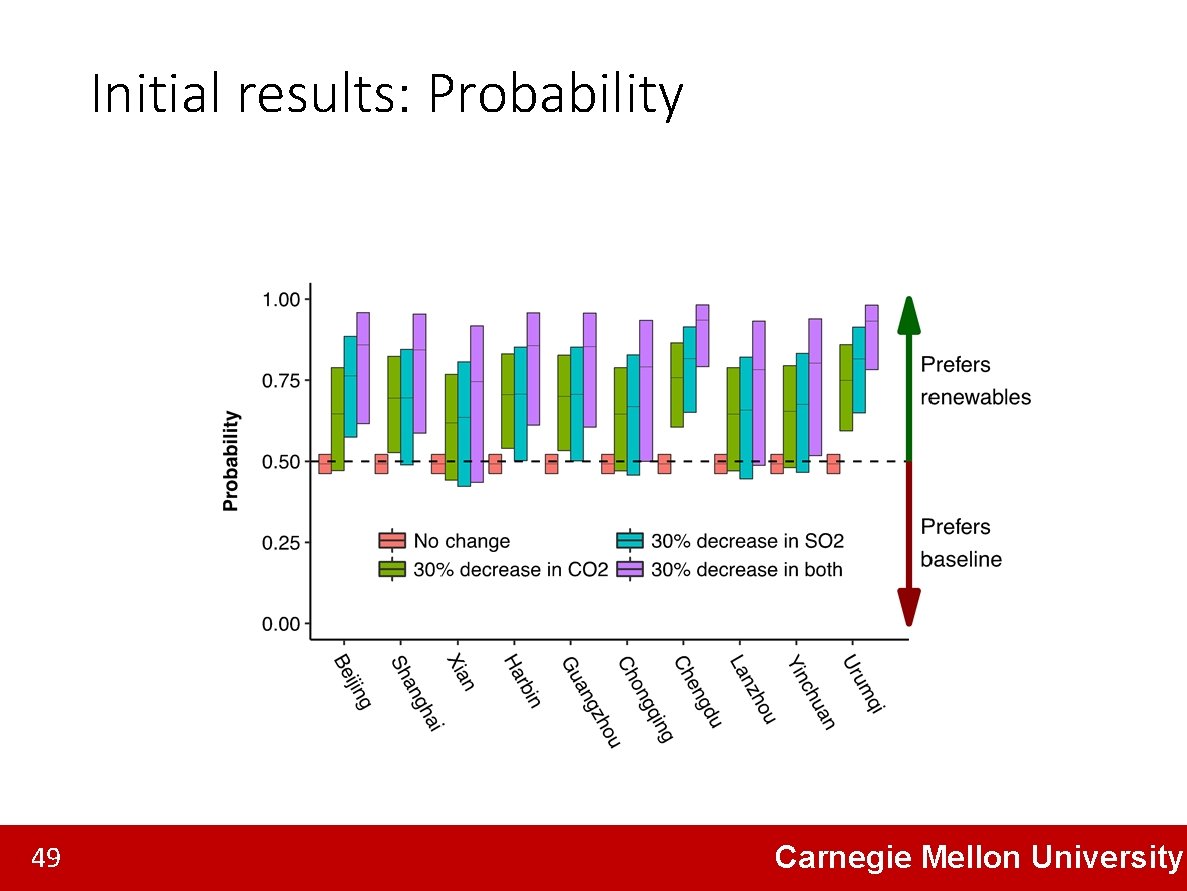

Initial results: Probability 49 49 Carnegie Mellon University