Using a Random Walk to simulate animal foraging

- Slides: 41

Using a “Random Walk” to simulate animal foraging behaviour Jim Barritt MSc Student Supervisors : Dr Stephen Hartley, Dr Marcus Frean Victoria University, Wellington School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2005

Talk outline • Background - Field results • What is a “Random walk”? • Results so far • Future work 1 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

Background • Part of a project investigating insect foraging interactions (Pieris rapae) • Dr. Stephen Hartley, Marc Hasenbank • Simulation in conjunction with field studies 2 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

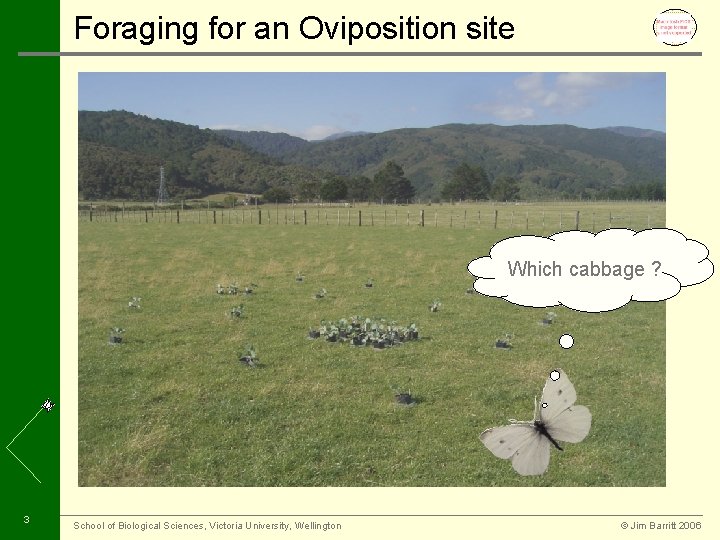

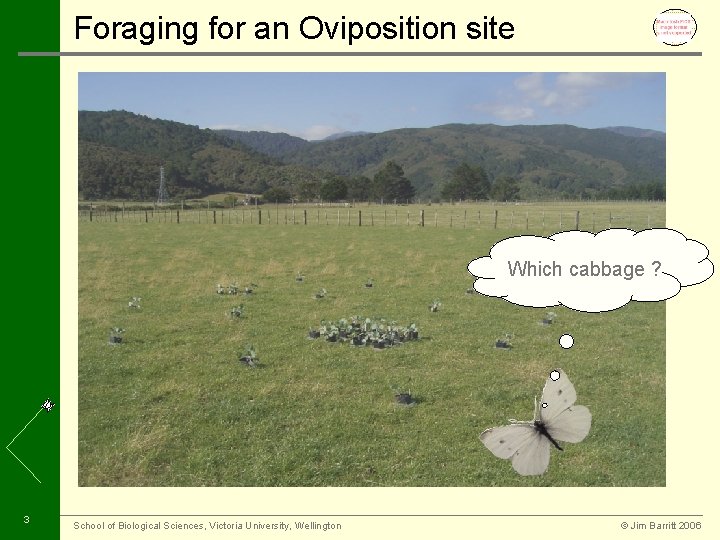

Foraging for an Oviposition site Which cabbage ? 3 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

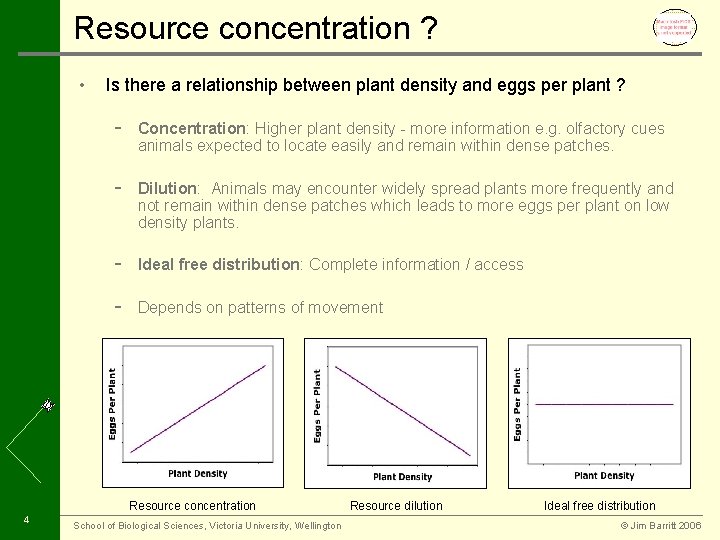

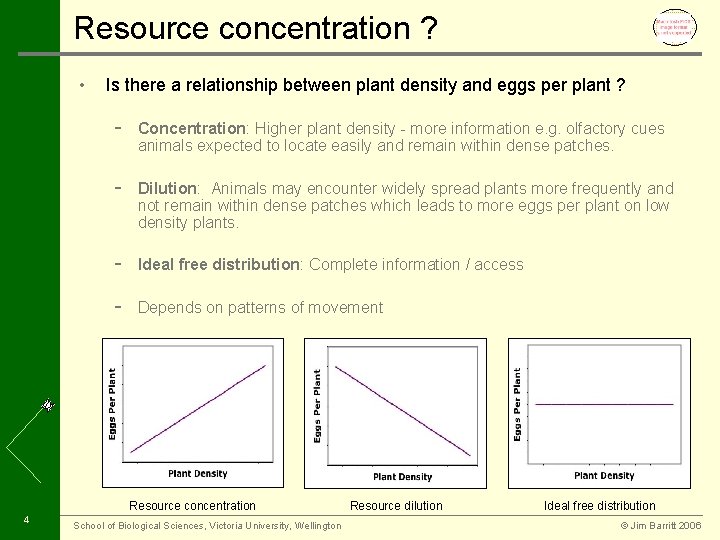

Resource concentration ? • Is there a relationship between plant density and eggs per plant ? - Concentration: Higher plant density - more information e. g. olfactory cues animals expected to locate easily and remain within dense patches. - Dilution: Animals may encounter widely spread plants more frequently and not remain within dense patches which leads to more eggs per plant on low density plants. - Ideal free distribution: Complete information / access - Depends on patterns of movement Resource concentration 4 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington Resource dilution Ideal free distribution © Jim Barritt 2006

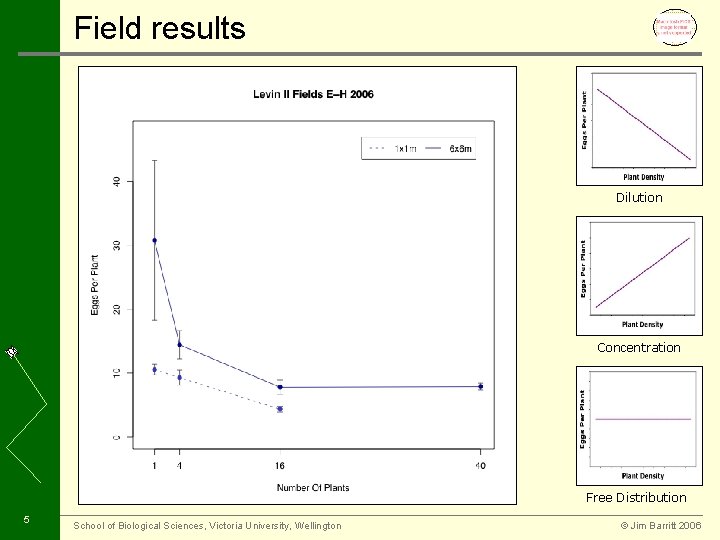

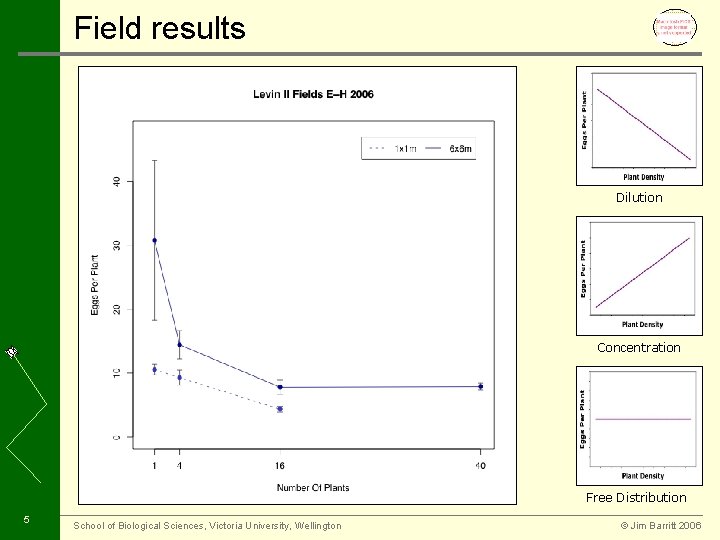

Field results Dilution Concentration Free Distribution 5 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

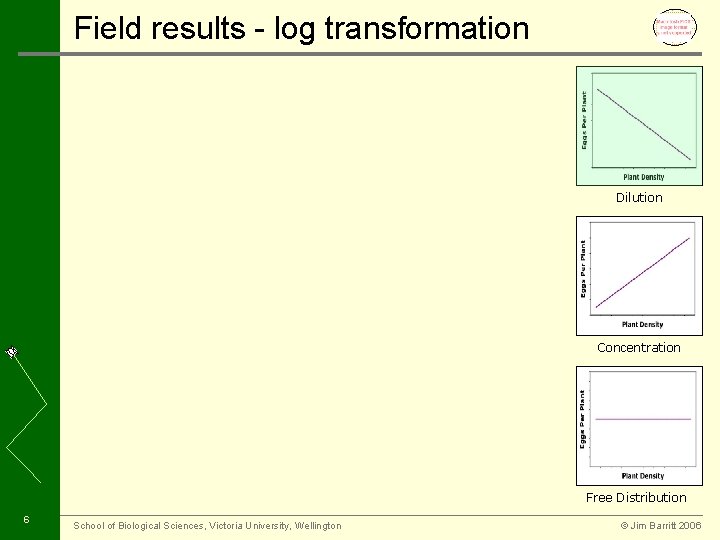

Field results - log transformation Dilution Concentration Free Distribution 6 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

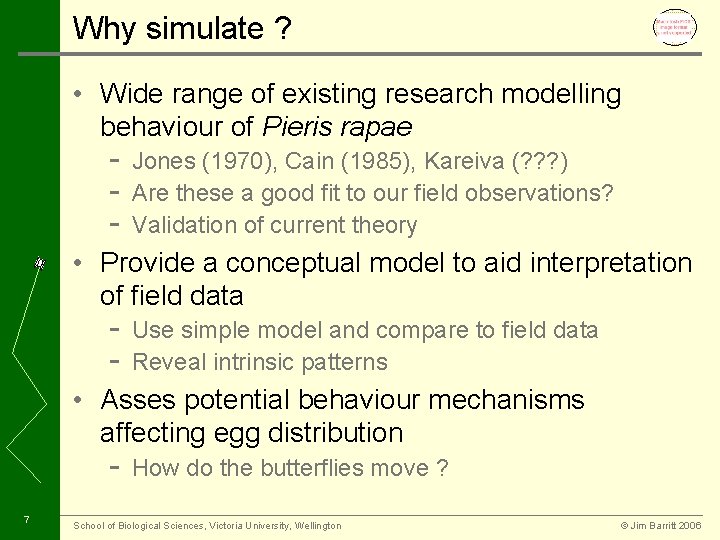

Why simulate ? • Wide range of existing research modelling behaviour of Pieris rapae - Jones (1970), Cain (1985), Kareiva (? ? ? ) Are these a good fit to our field observations? Validation of current theory • Provide a conceptual model to aid interpretation of field data - Use simple model and compare to field data Reveal intrinsic patterns • Asses potential behaviour mechanisms affecting egg distribution - 7 How do the butterflies move ? School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

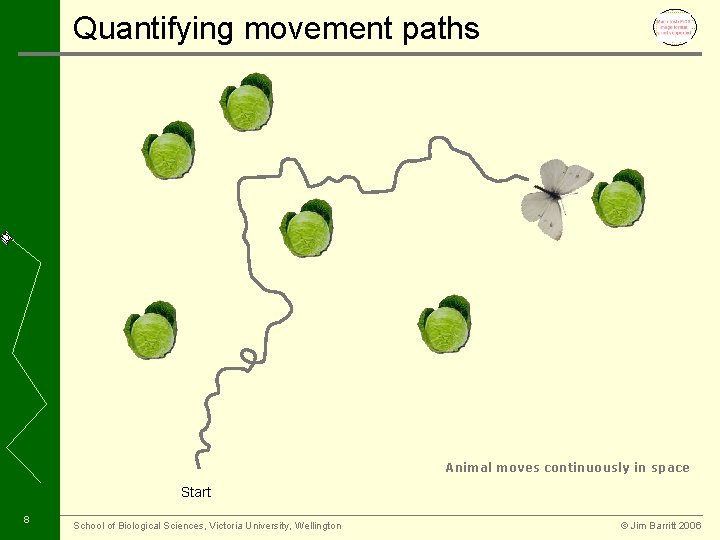

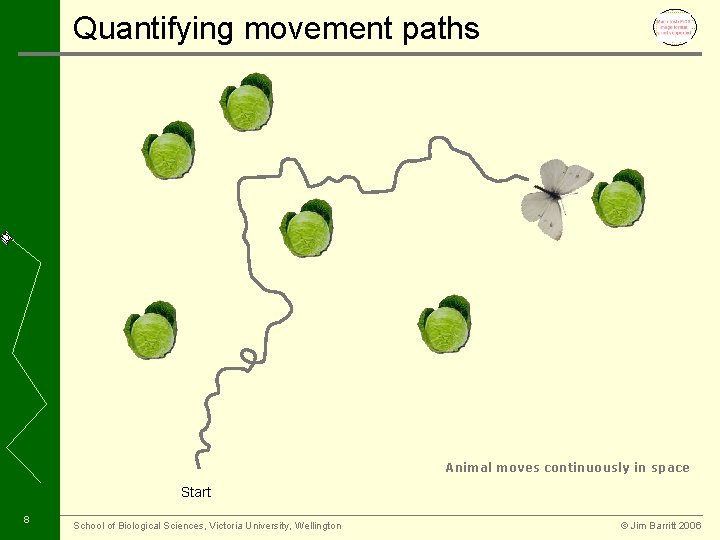

Quantifying movement paths Animal moves continuously in space Start 8 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

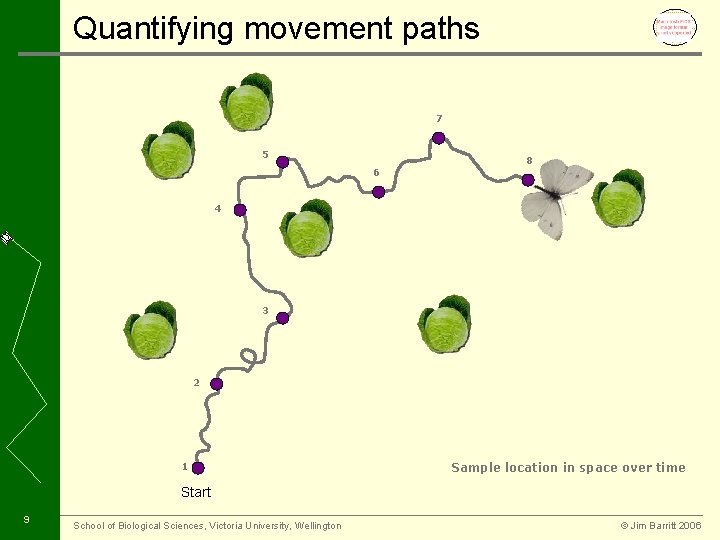

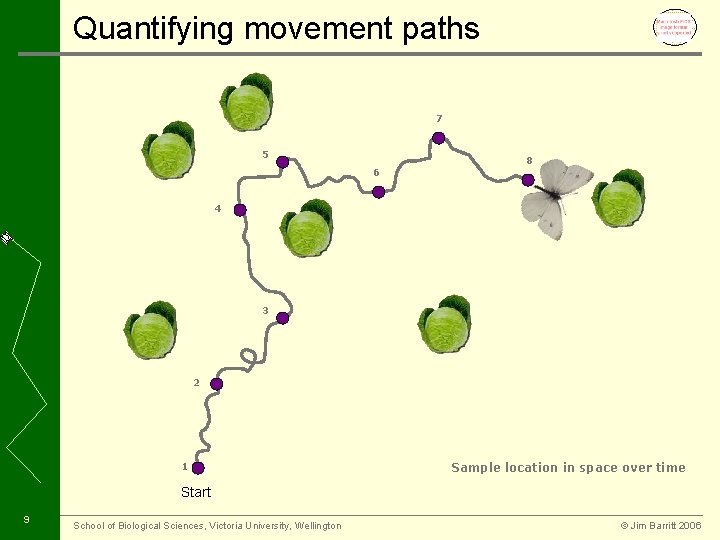

Quantifying movement paths 7 5 6 8 4 3 2 1 Sample location in space over time Start 9 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

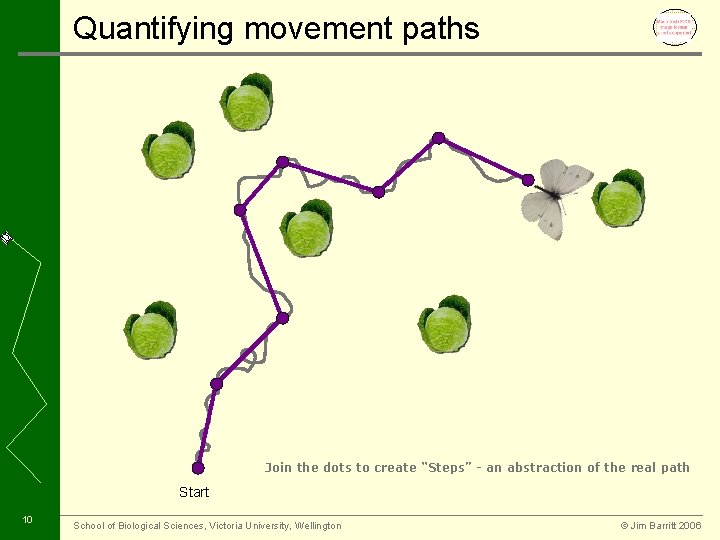

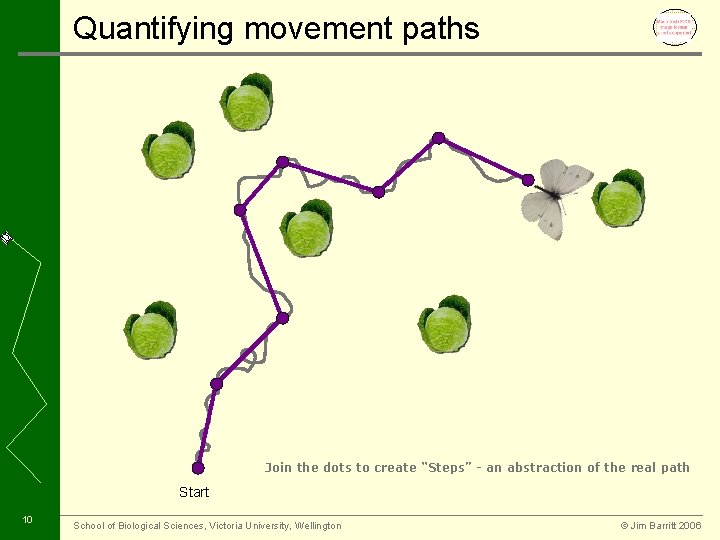

Quantifying movement paths Join the dots to create “Steps” - an abstraction of the real path Start 10 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

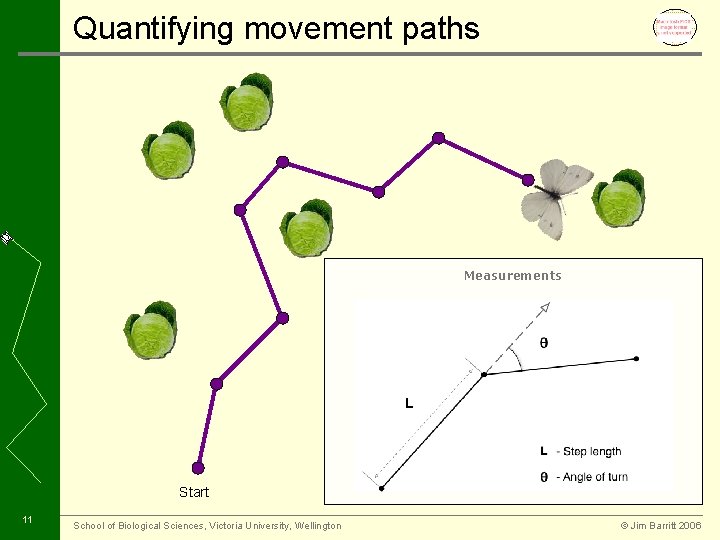

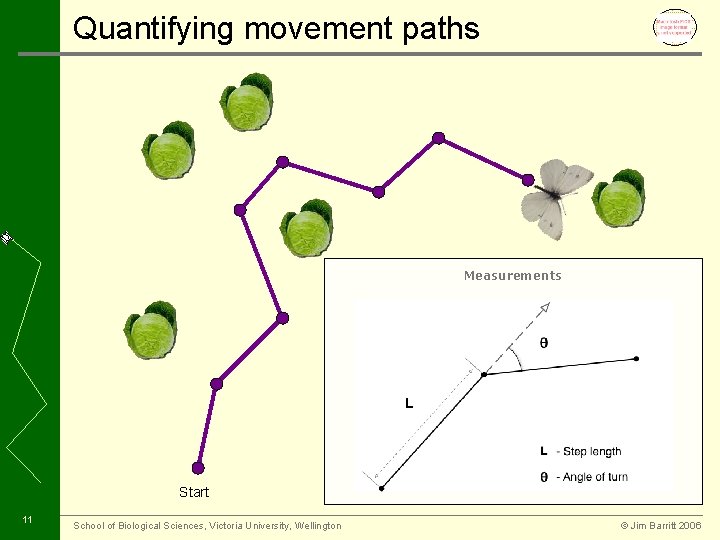

Quantifying movement paths Measurements Start 11 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

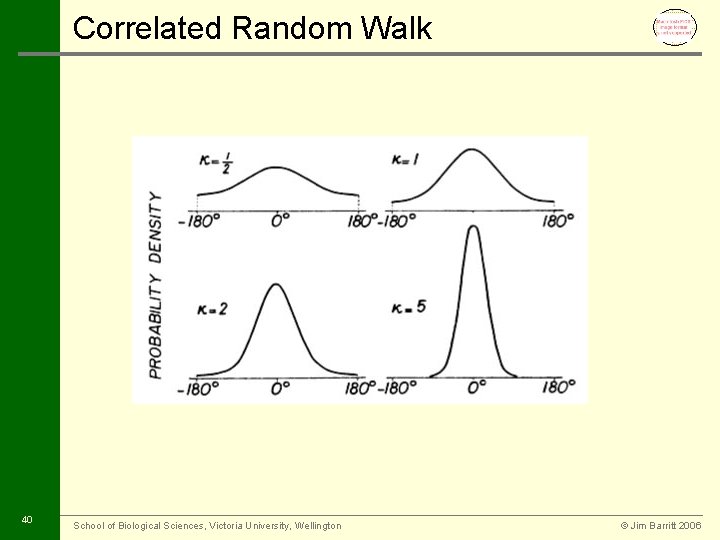

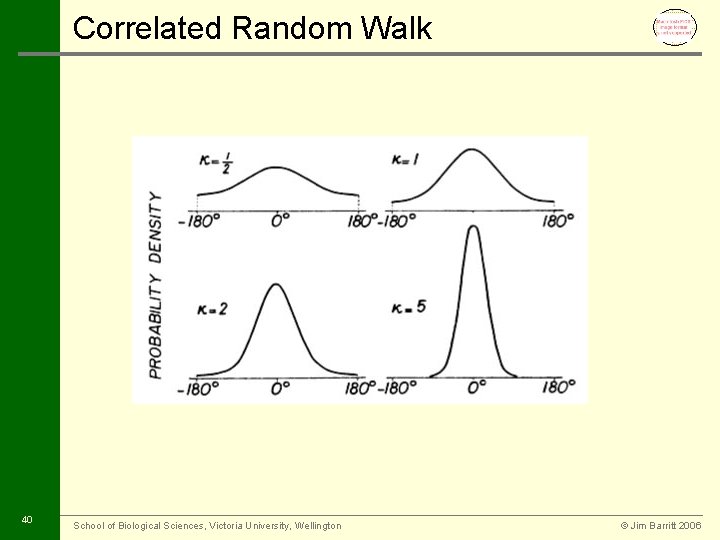

Random walks • Can use same parameters to recreate paths in a simulation • Do an example of a simple random walk • “Pure random” vs “Correlated random” • Parameters A and L 12 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

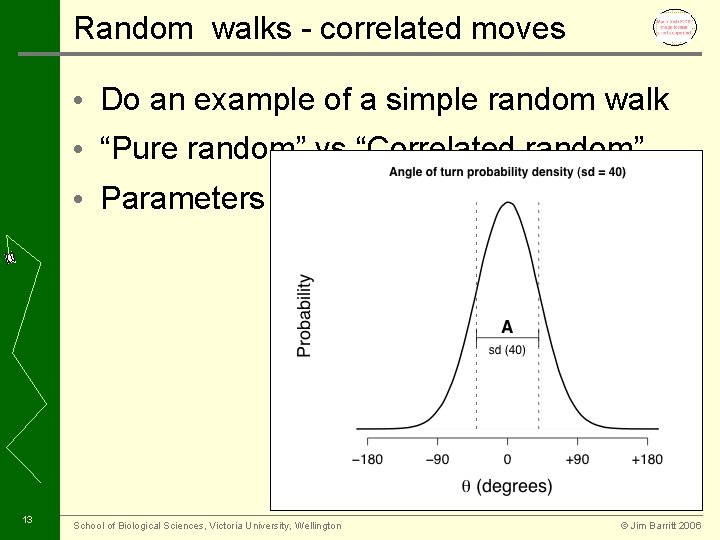

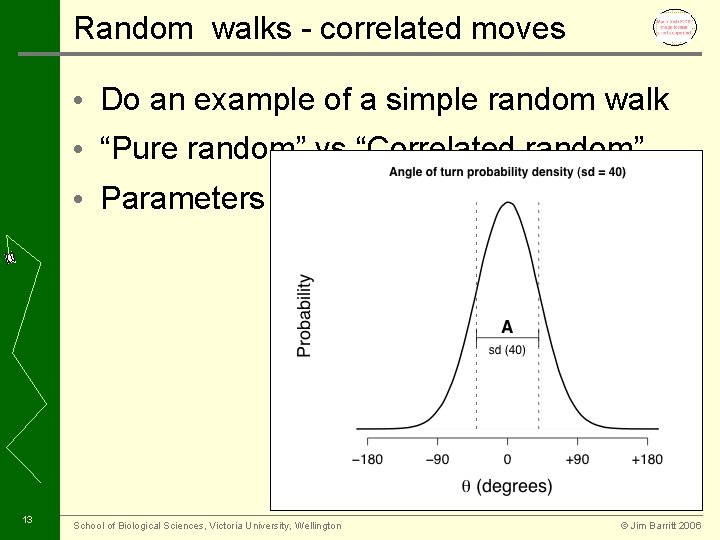

Random walks - correlated moves • Do an example of a simple random walk • “Pure random” vs “Correlated random” • Parameters A and L 13 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

Simulation • Demonstration with simple layout • Experimental layout - Same as the field layout • Parameters • Results 14 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

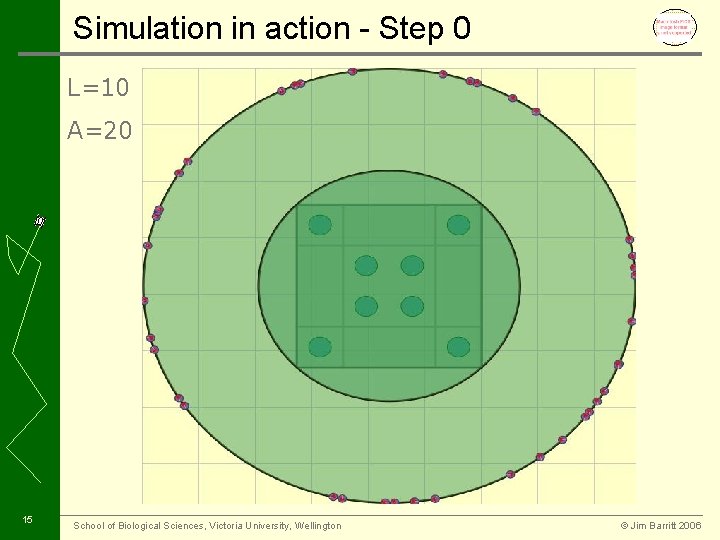

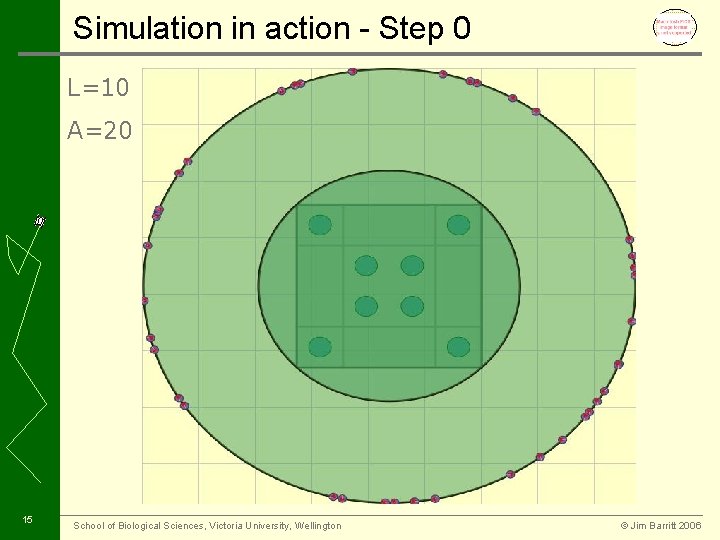

Simulation in action - Step 0 L=10 A=20 15 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

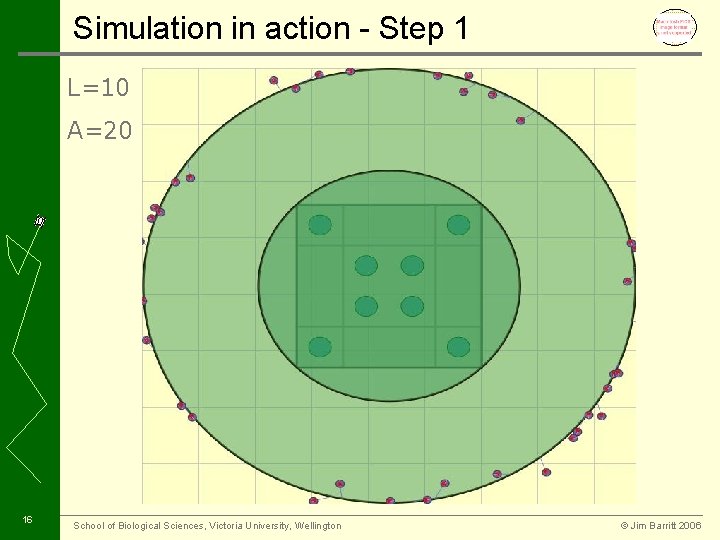

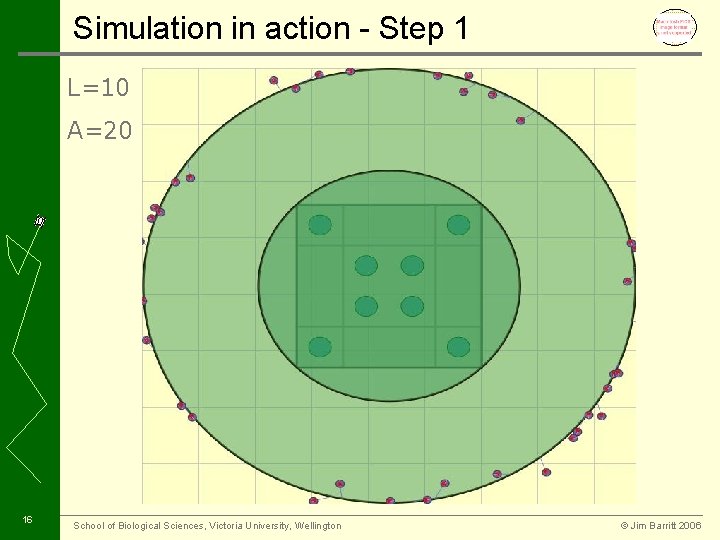

Simulation in action - Step 1 L=10 A=20 16 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

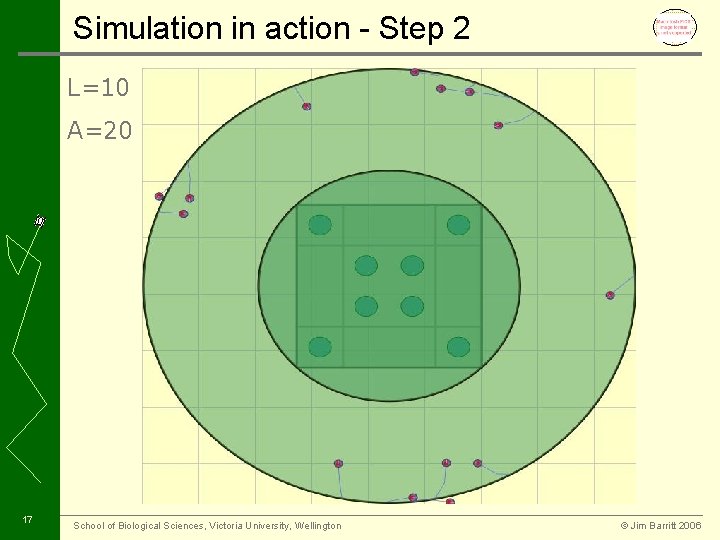

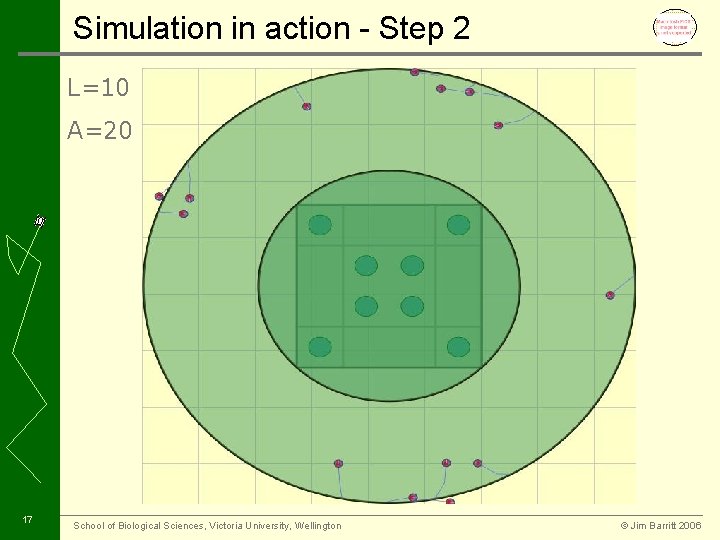

Simulation in action - Step 2 L=10 A=20 17 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

Simulation in action - Step 3 L=10 A=20 18 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

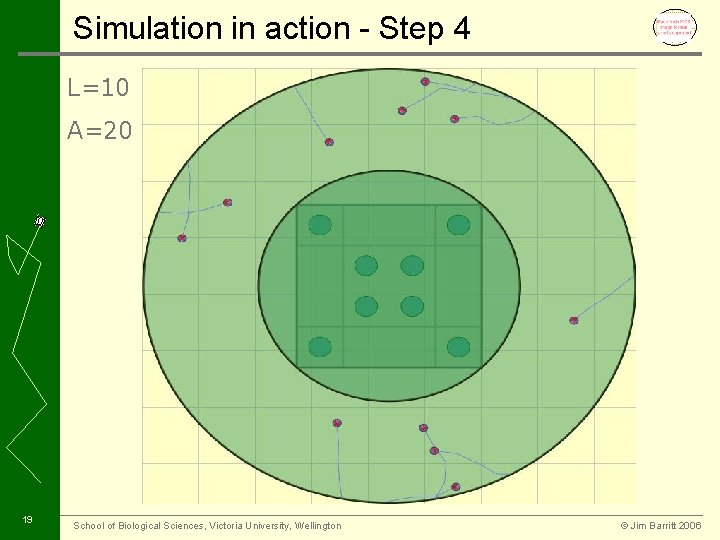

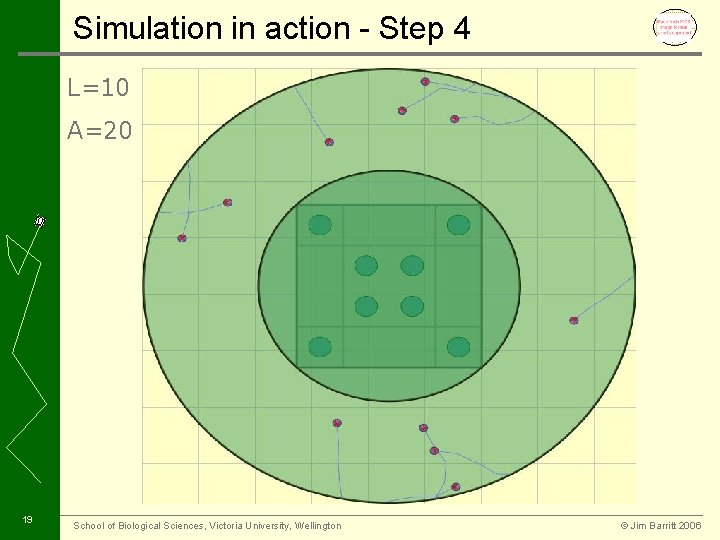

Simulation in action - Step 4 L=10 A=20 19 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

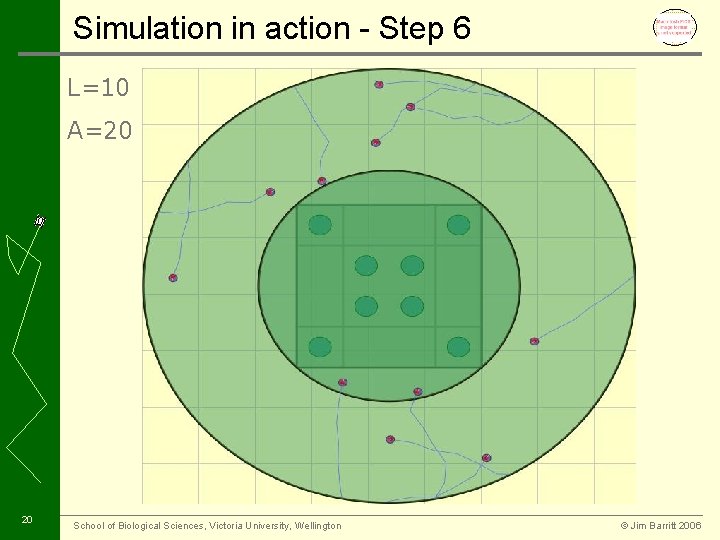

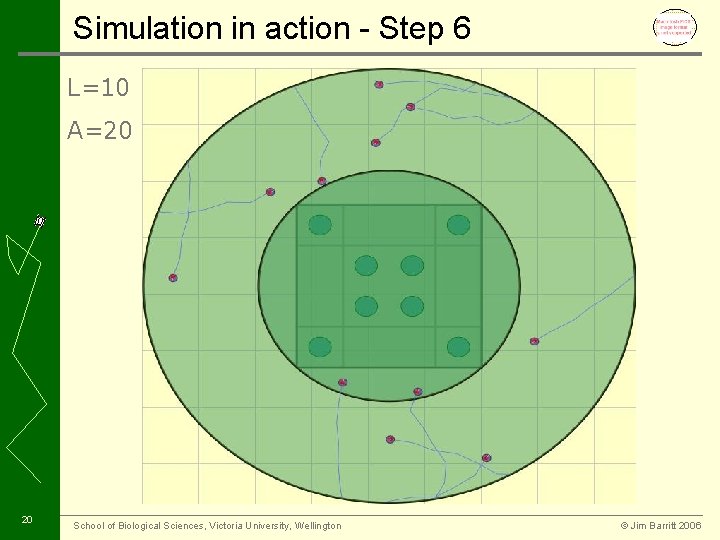

Simulation in action - Step 6 L=10 A=20 20 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

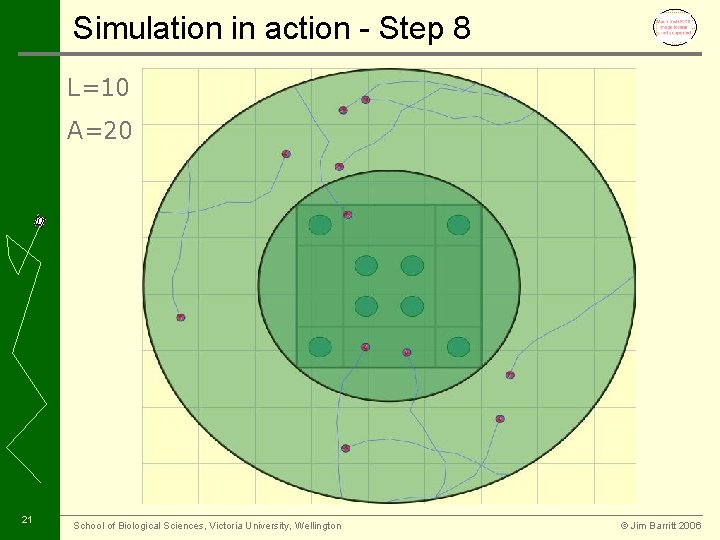

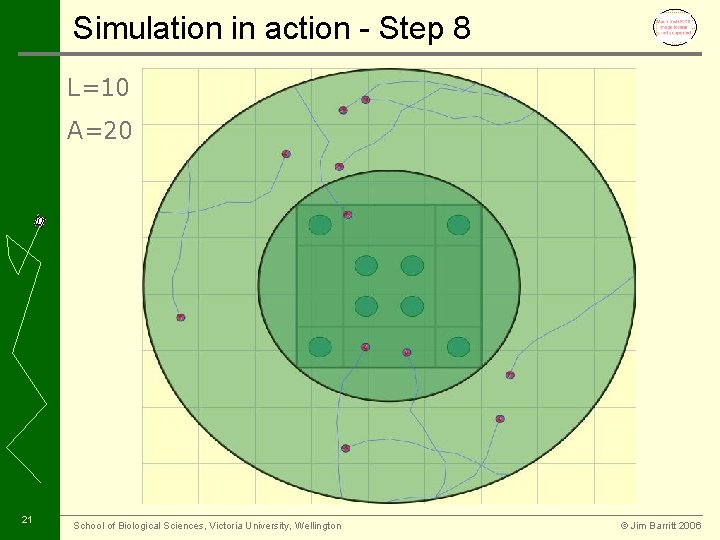

Simulation in action - Step 8 L=10 A=20 21 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

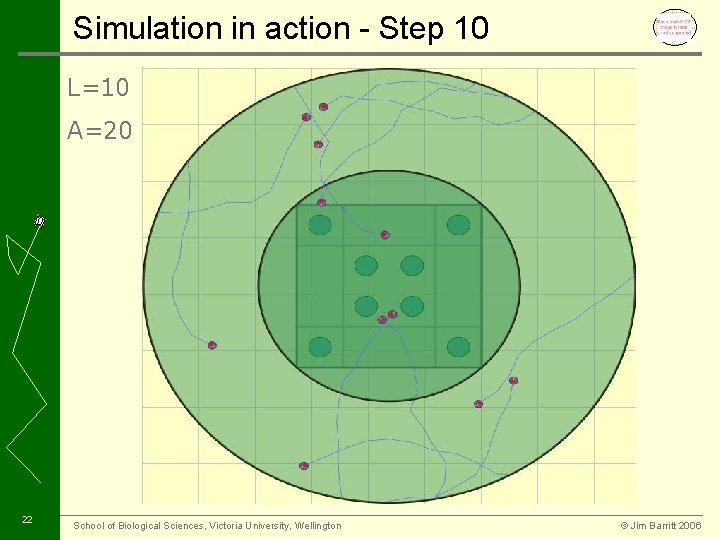

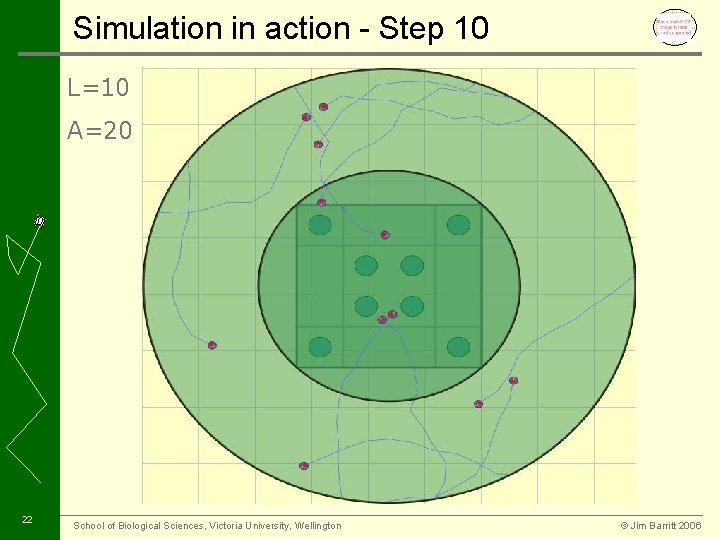

Simulation in action - Step 10 L=10 A=20 22 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

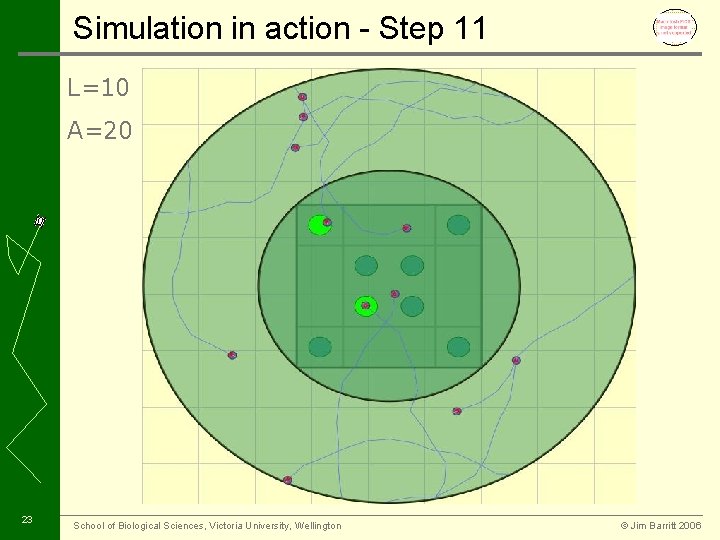

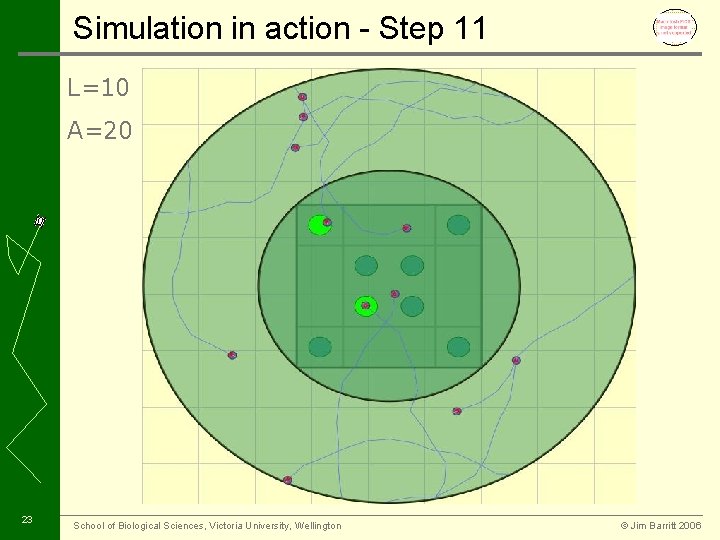

Simulation in action - Step 11 L=10 A=20 23 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

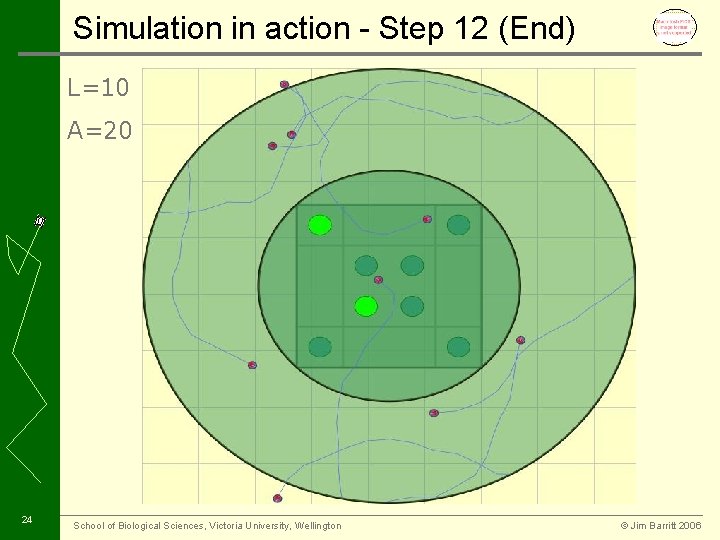

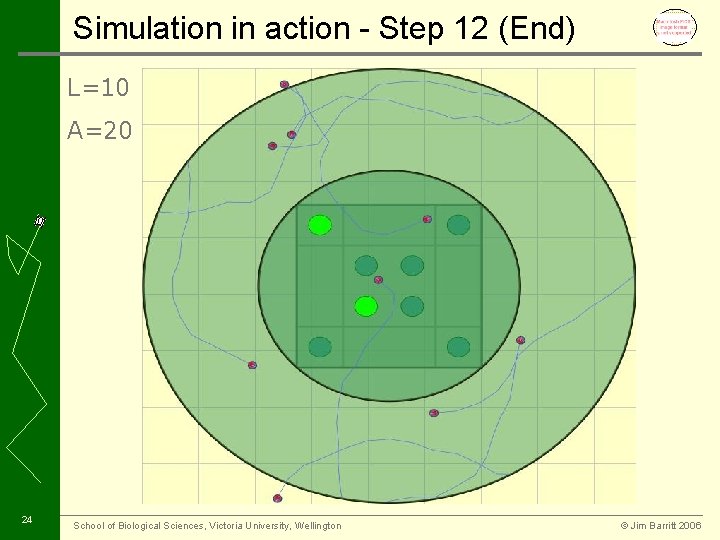

Simulation in action - Step 12 (End) L=10 A=20 24 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

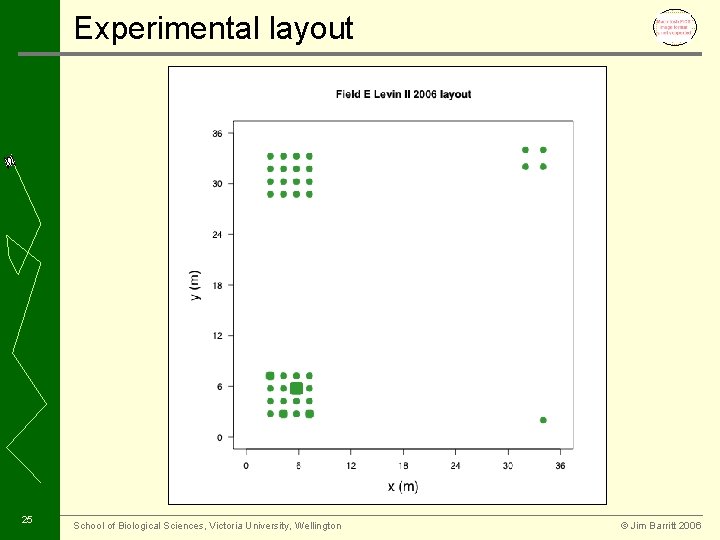

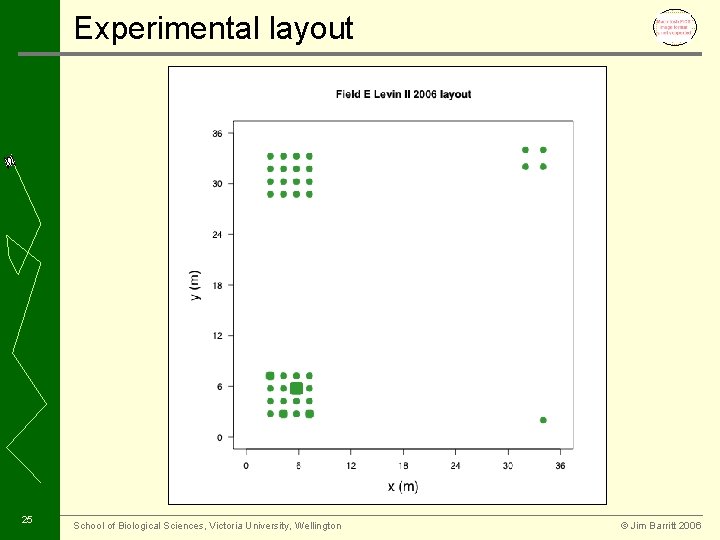

Experimental layout 25 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

Experiment Parameters • L = Step Length (0. 5 m to 2 m) • A = SD Angle of turn (20 to 100 degrees) • 10, 000 butterflies • 10 replicates • Published: Root(xxxx) - A - 90 degrees - L - Varies 26 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

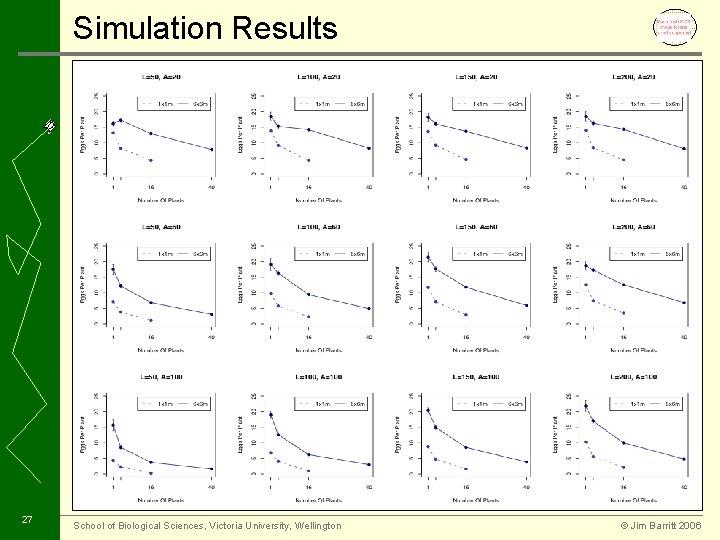

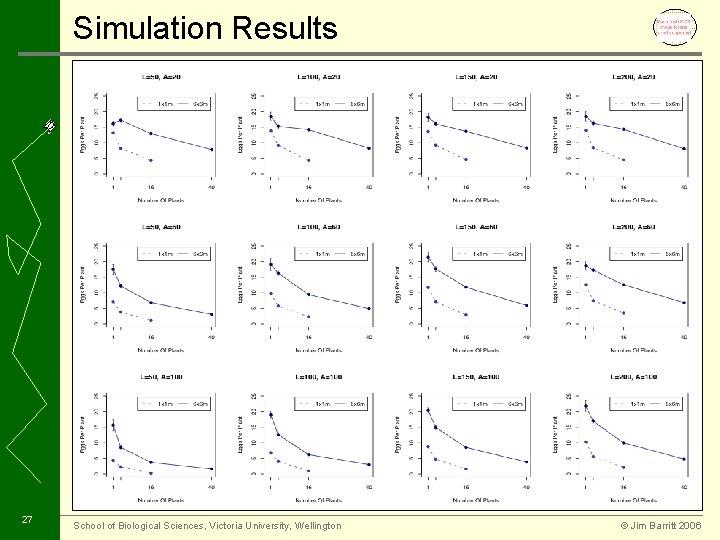

Simulation Results 27 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

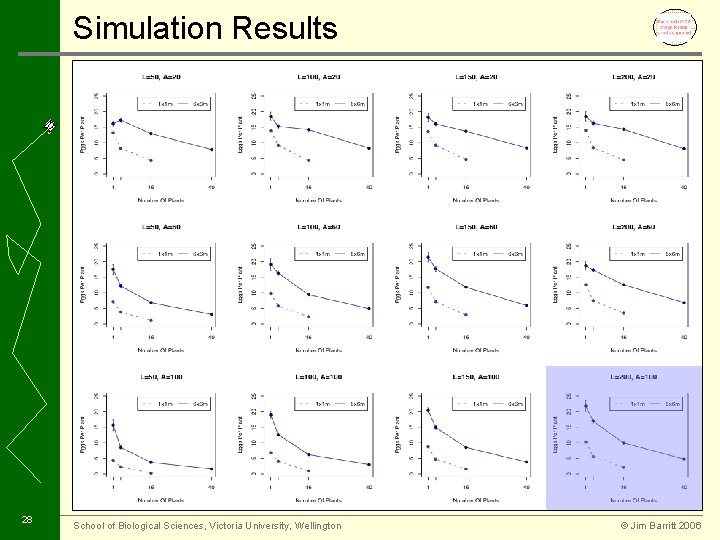

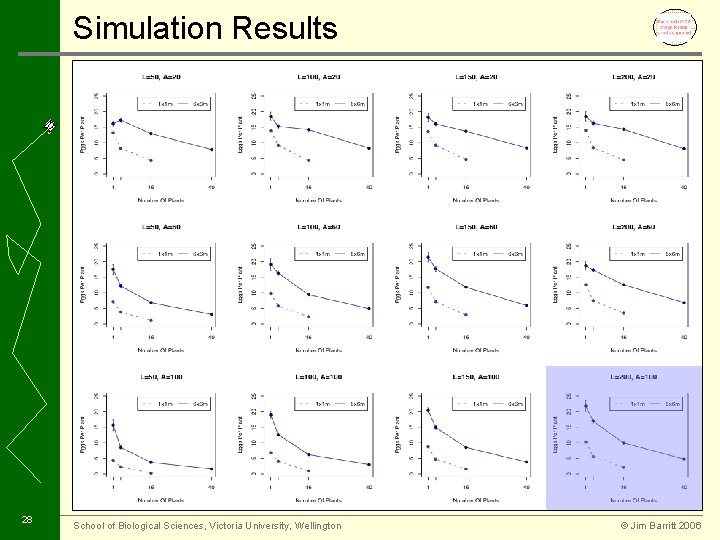

Simulation Results 28 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

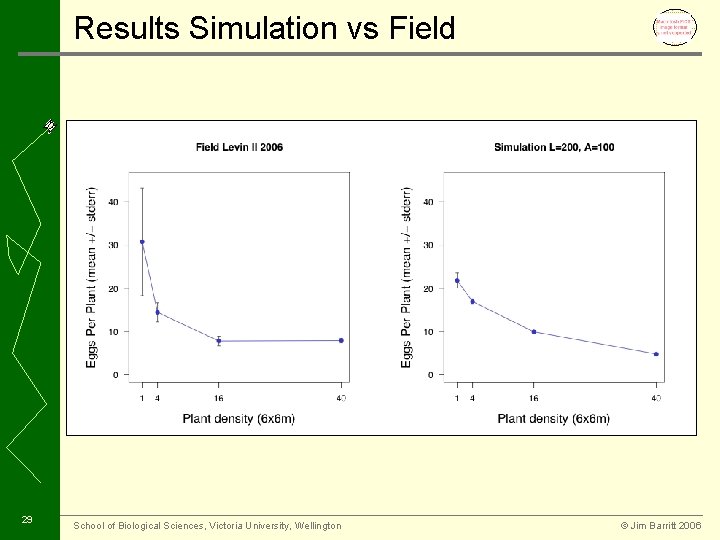

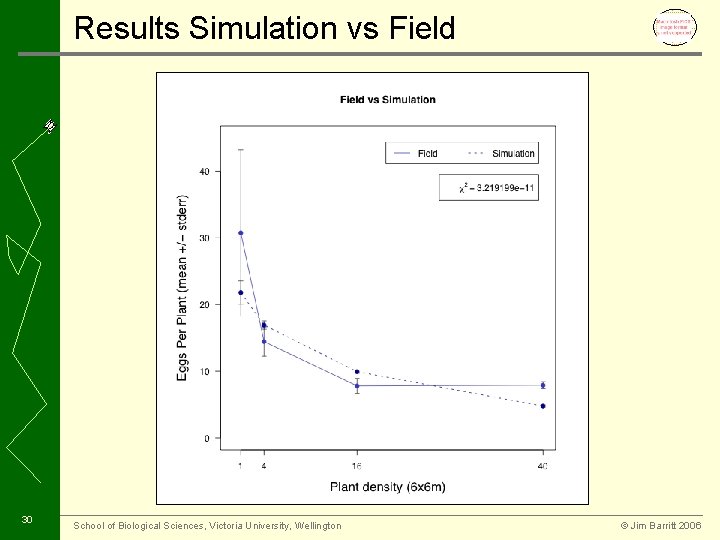

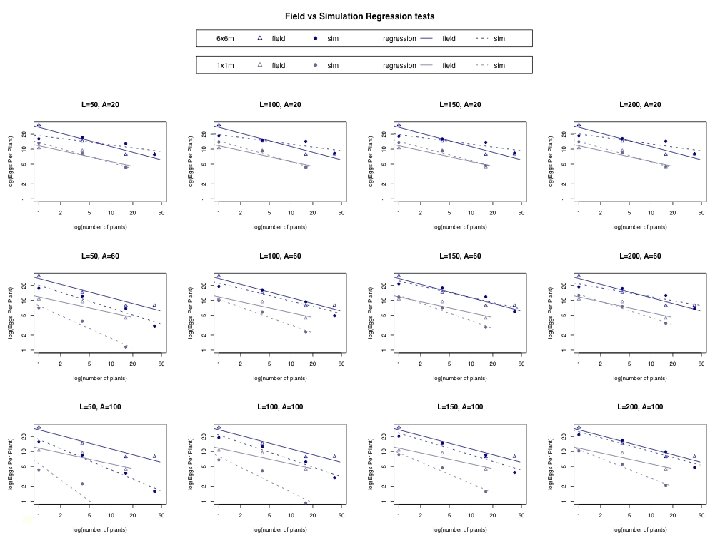

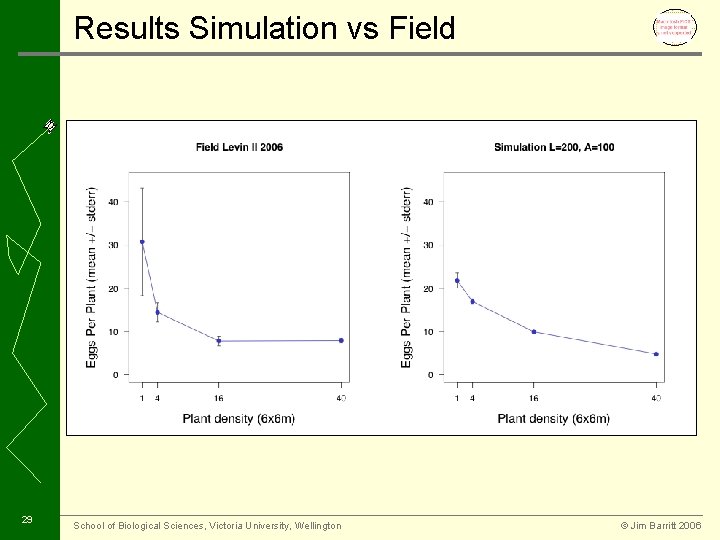

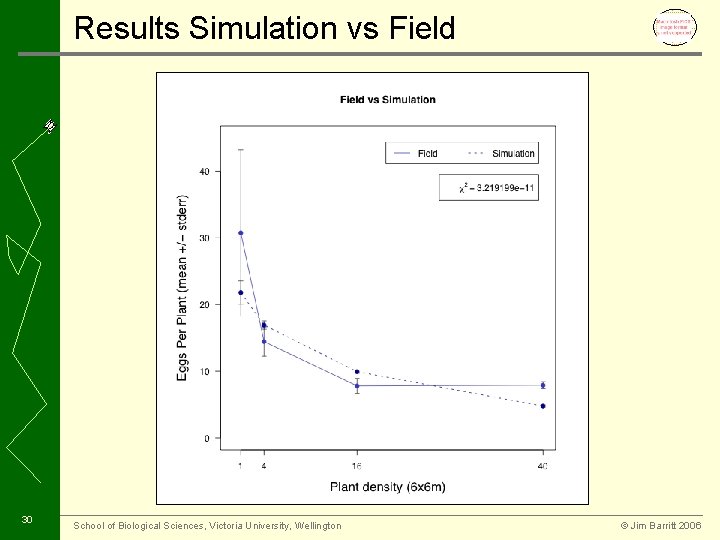

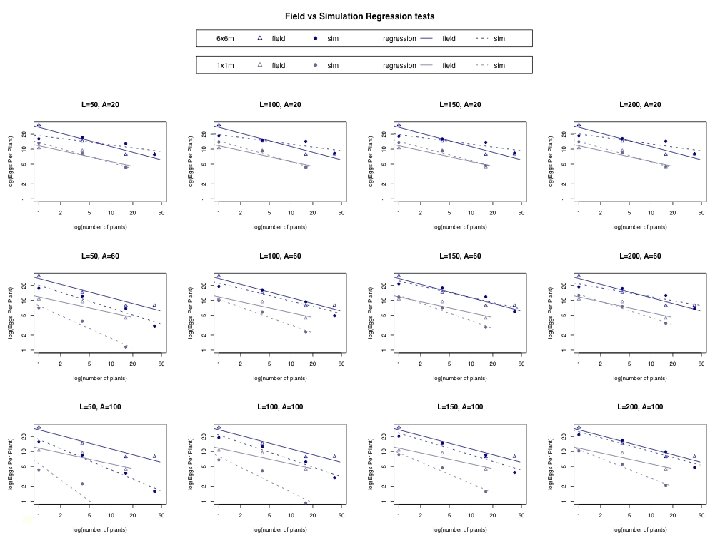

Results Simulation vs Field 29 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

Results Simulation vs Field 30 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

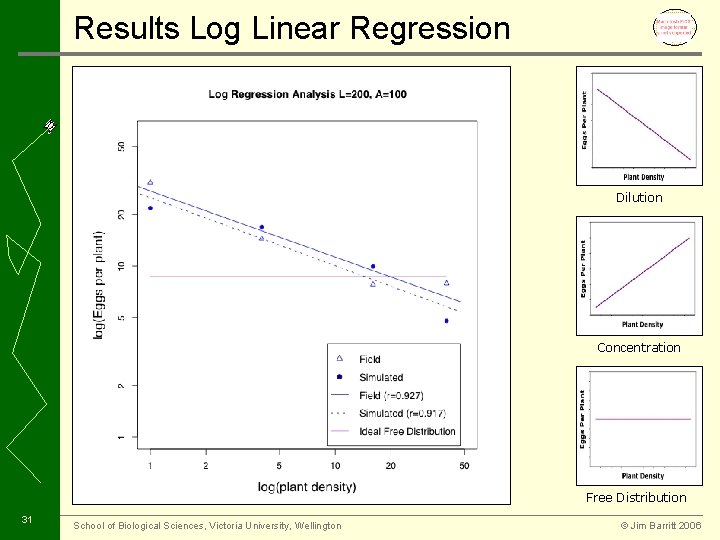

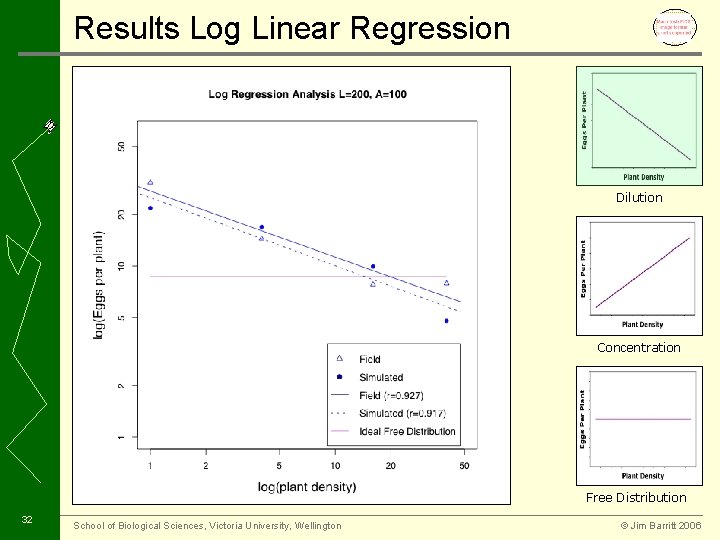

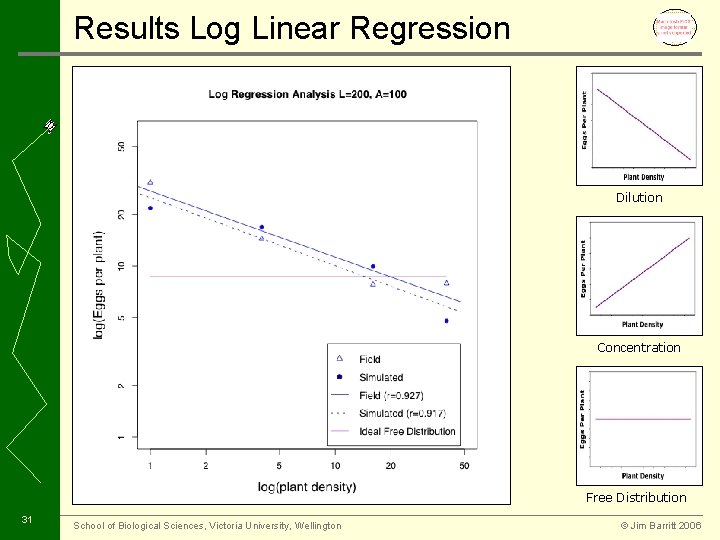

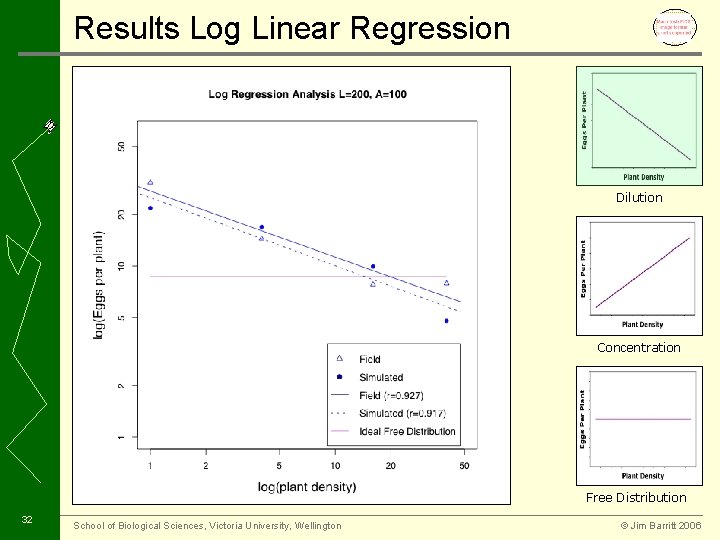

Results Log Linear Regression Dilution Concentration Free Distribution 31 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

Results Log Linear Regression Dilution Concentration Free Distribution 32 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

Statistical tests • Chi Squared to compare egg distributions - All significantly different to field (p<0. 001) • Log Linear regression analysis to compare slope of response - No significant differences to field - All show resource dilution 33 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

Conclusions • Observed resource dilution - In both simulation and field results • Simple random walk does not represent field results exactly - 34 Saw change in effect for lower step length Change parameters Change behaviour algorithm More than 1 egg Space agents School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

Future Work • Deterministic attraction - Force of attraction (similar to gravity) Perceptual ranges Information gradients / matrix • Random walk influenced by Environment - Move length and Angle of turn as functions of information gradients • Lifecycle: migration, multiple eggs and birth • Multi species - Co-existance? • Different responses at different scales? 35 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

Acknowledgements • Thanks to - Dr Stephen Hartley Dr Marcus Frean Marc Hasenbank Victoria University Bug Group - Special thanks to John Clark and the staff of Woodhaven Farm (Levin) http: //www. oulu. fi/ 36 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

Questions ? • Simulation of insect foraging - Random Walks - Observed similar trends to field data • Future work - Include deterministic attraction - Can we observe different responses at different scales ? • 37 jim@planet-ix. com School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

References Aldrich, J. (1997). R. A. Fisher and the making of maximum likelihood 1912 -1922. Statistical Science 12, pp. 162 -176. Bukovinszky, T. , R. P. J. Potting, Y. Clough, J. C. van Lenteren, and L. E. M. Vet. (2005). The role of pre- and post-alighting detection mechanisms in the responses to patch size by specialist herbivores. Oikos 109, pp. 435 -446. Byers, J. A. (2001). Correlated random walk equations of animal dispersal resolved by simulation. Ecology 82, pp. 1680 -1690. Cain, M. L. (1985). Random Search by Herbivorous Insects: A Simulation Model. Ecology 66, pp. 876 -888. Finch, S. , and R. H. Collier. (2000). Host-plant selection by insects - a theory based on 'appropriate/inappropriate landings' by pest insects of cruciferous plants. Entomologia Experimentalis Et Applicata 96, pp. 91 -102. Fretwell, S. D. , and H. L. Lucas. (1970). On territorial behaviour and other factors influencing habitat distribution in birds. Acta Biotheoretica 19, pp. 16 -36. Grez, A. A. , and R. H. Gonzalez. (1995). Resource Concentration Hypothesis - Effect of Host-Plant Patch Size on Density of Herbivorous Insects. Oecologia 103, pp. 471 -474. Holmgren, N. M. A. , and W. M. WGetz. (2000). Evolution of host plant selection in insect under perceptual constraints: A simulation study. Evolutionary Ecology Research 2, pp. 81 -106. Jones, R. E. (1977). Movement Patterns and Egg Distribution in Cabbage Butterflies. The Journal of Animal Ecology 46, pp. 195 -212. Olden, J. D. , R. L. Schooley, J. B. Monroe, and N. L. Poff. ( 2004). Context-dependent perceptual ranges and their relevance to animal movements in landscapes. Journal of Animal Ecology 73, pp. 1190 -1194. Otway, S. J. , A. Hector, and J. H. Lawton. (2005). Resource dilution effects on specialist insect herbivores in a grassland biodivers ity experiment. Journal of Animal Ecology 74, pp. 234 -240. Root, R. B. (1973). Organization of a Plant-Arthropod Association in Simple and Diverse Habitats: The Fauna of Collards ( Brassica Oleracea). Ecological Monographs 43, pp. 95 -124. Tilman, D. , and P. M. Kareiva. (1997). Spatial Ecology: The Role of Space in Population Dynamics and Interspecific Interactions. Monographs In Population Biology 30 38 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

39 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006

Correlated Random Walk 40 School of Biological Sciences, Victoria University, Wellington © Jim Barritt 2006