Urinary Tract Infection Diagnosis Zahra Pournasiri MD Pediatric

- Slides: 35

Urinary Tract Infection: Diagnosis Zahra Pournasiri, MD Pediatric Nephrologist, Shahid Beheshti University Of Medical Science www. drpournasiri. com

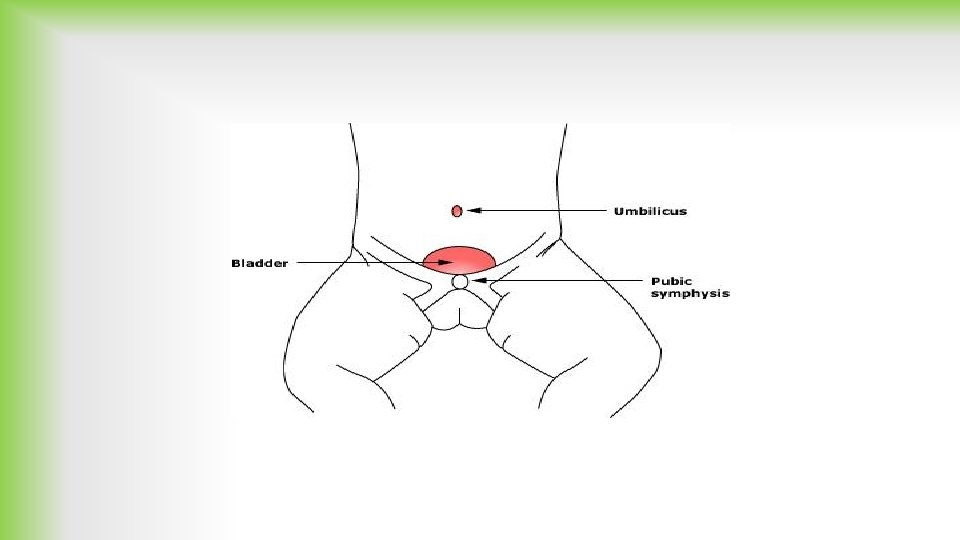

Urine collection methods • • There are four techniques for collecting a urine sample in children: Non-invasive techniques : A bag applied to the perineum Clean catch midstream void, Invasive methods : Bladder catheterization Suprapubic aspiration (SPA).

Urine collection methods • In toilet-trained children, the method of choice for diagnosing a UTI is a clean voided midstream urine sample

A bag sampling • Bag sampling can be done from 2 months to 2 years. • An AAP technical report states that up to 85% of positive culture results obtained by using a collection bag can be false positives. • the negative predictive value for urinalysis from a “bag” specimen is 99%. • If treatment is planned immediately after obtaining the urine culture, a bagged specimen should not be the method.

Clean catch midstream void • In toilet-trained children, the method of choice for diagnosing a UTI is a clean voided midstream urine sample • Firstly, pass a small amount of urine into the toilet and then start collecting your urine into the container—do not touch the inside of the container. You do not have to fill the container to the brim. • No benefit to cleansing the introitus before obtaining the specimen ? ? • Contact of the urinary stream with the mucosa should be minimized by pulling back the foreskin in boys who are uncircumcised and by spreading the labia in girls.

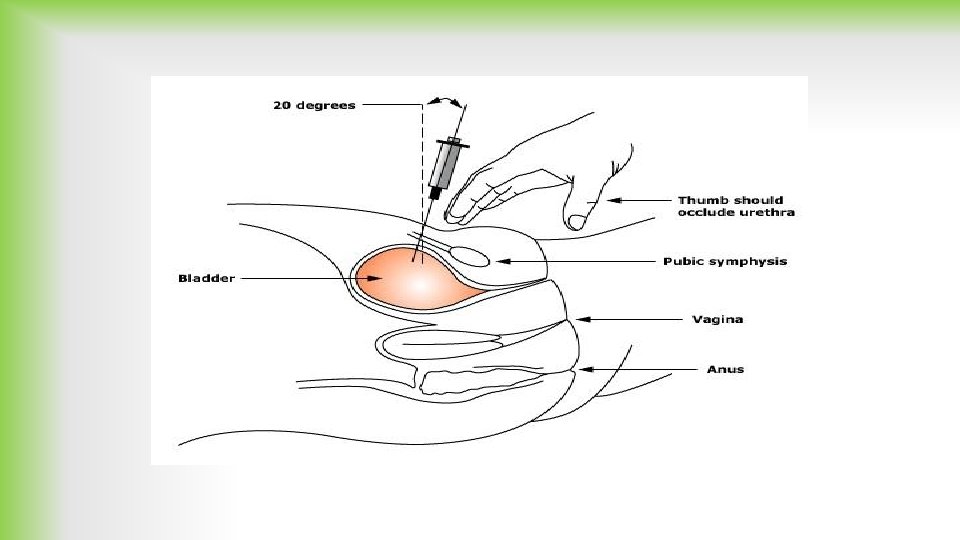

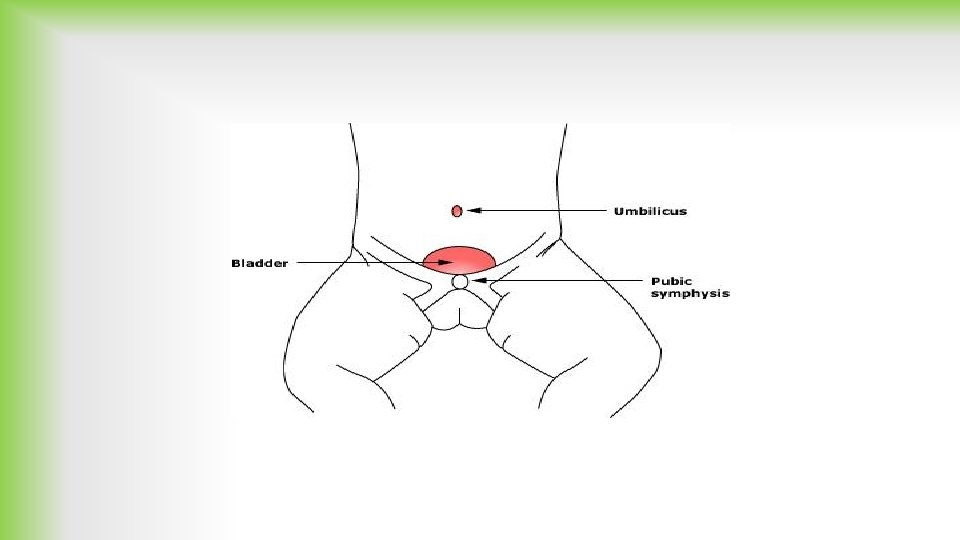

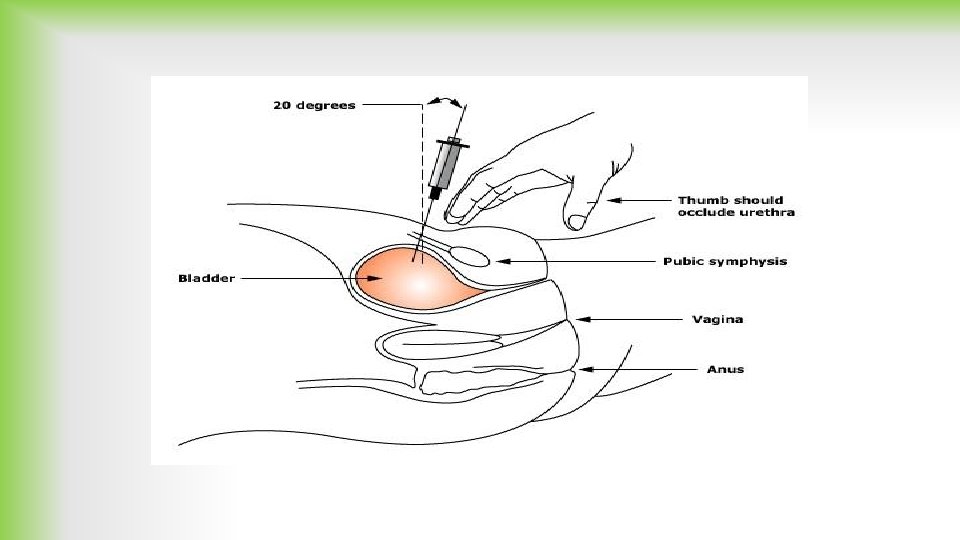

SUPRAPUBIC BLADDER ASPIRATION (SPA) LIMITATION: • Its limited success rate (25%– 60%) • Another limitation is the associated pain that has been reported to be greater than for urethral catheterization • Not performed in children who are older than two years • Complications : Ø Minor complications, such as microscopic hematuria, are common, Ø gross hematuria Ø anterior abdominal wall abscess, Ø Intestinal perforation can occur if a loop of bowel overlies the bladder, but the small puncture rarely leads to peritonitis Ø Intestinal (or other viscus) perforation can be avoided if the procedure is not performed in children who have abdominal distension, organomegaly, volume depletion, or congenital anomalies of the gastrointestinal or genitourinary tract

PROCESSING OF URINE SAMPLES • The specimen should be examined within 60 -120 minutes of voiding • If such immediate dispatch is not possible, the container should be transported in iced water and then stored in a refrigerator at 4ºC. Cooling stops bacterial growth until the urine is plated on culture medium and incubated. However, urinary leukocytes may be altered by refrigeration, possibly affecting interpretation of the urinalysis. • A small amount of sediment should be placed on a slide, while the supernatant should be tested for color (particularly for color suggesting the presence of heme pigments), protein, p. H, concentration, and glucose.

TRANSURETHRAL BLADDER CATHETERIZATION (TUBC) • The AAP technical report also states that SPA has higher pain scores and lower success rates than bladder catheterization, • The child is restrained in the supine and frog leg position. This position permits adequate stabilization of the pelvis and complete visualization of the external genitalia. • The anterior urethra is cleansed thoroughly with povidone-iodine solution. • A sterile lubricant jelly is applied to the end of an appropriately sized catheter (5 French for children younger than 6 months; 8 French for those between 6 months and adolescence, and 10 French for adolescents) • Complications : urethral trauma and microscopic hematuria. iatrogenic infection.

Final Decision 1. Clean catch mid-stream void 2. Bladder catheterization 3. Suprapubic aspiration

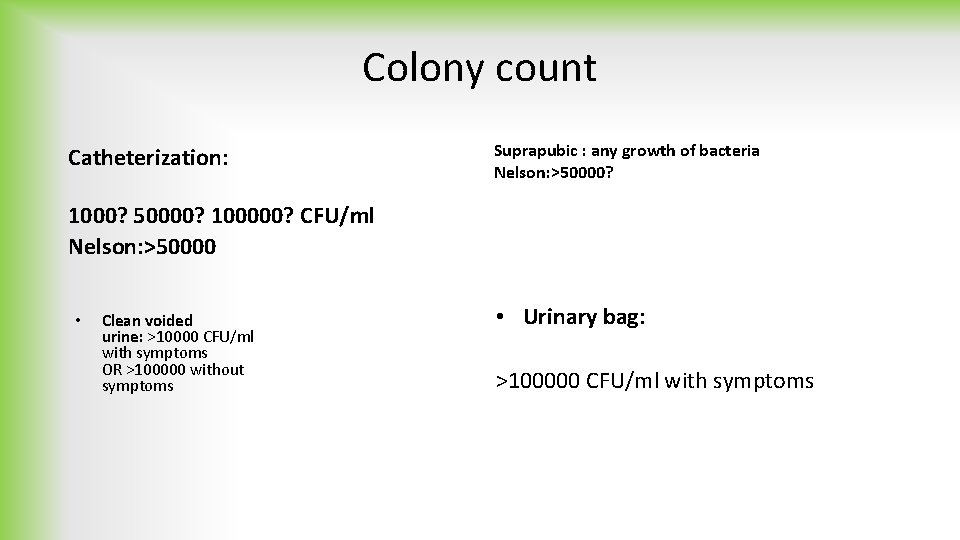

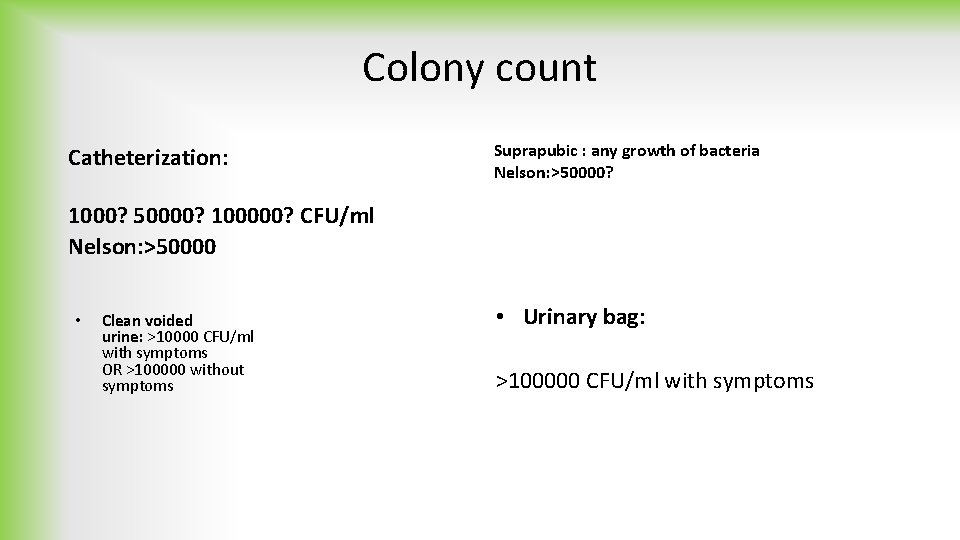

Colony count Catheterization: Suprapubic : any growth of bacteria Nelson: >50000? 1000? 50000? 100000? CFU/ml Nelson: >50000 • Clean voided urine: >10000 CFU/ml with symptoms OR >100000 without symptoms • Urinary bag: >100000 CFU/ml with symptoms

Urinalysis in UTI

• If the child is asymptomatic and the urinalysis result is normal, it is unlikely that there is a UTI. • However, if the child is symptomatic, a UTI is possible, even if the urinalysis result is negative, and the urine culture should be monitored.

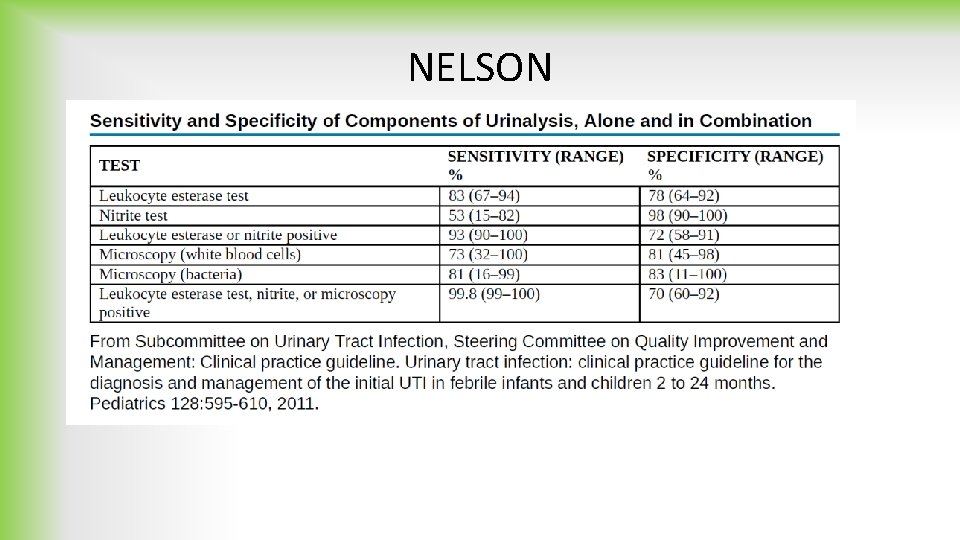

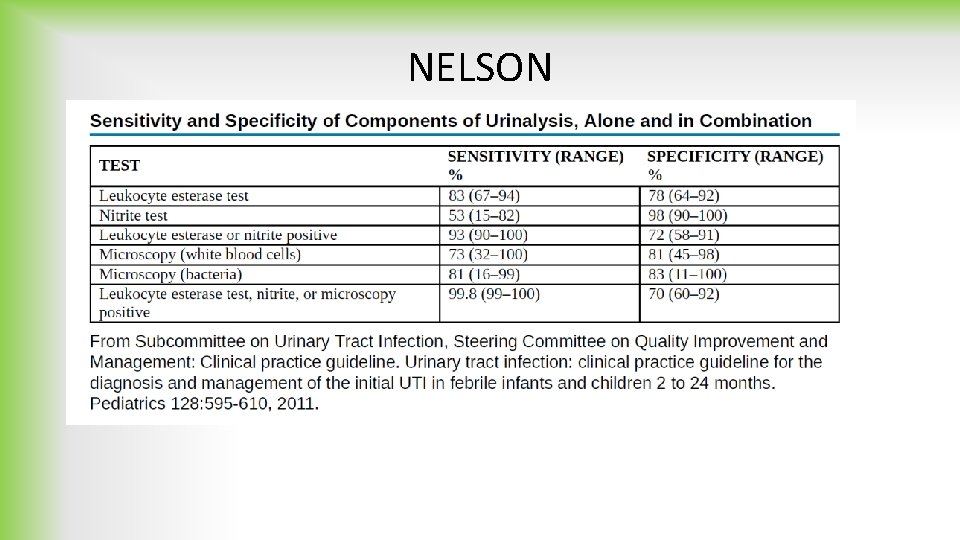

White blood cells • In the microscopic analysis of centrifuged urine, five WBCs per high -power field is a usual threshold for pyuria. • Another method is automatic counting in uncentrifuged urine, with 10 WBCs being a threshold value. • Sensivity: 73% specifity: 81% • WBC casts in the urinary sediment suggest renal involvement, but in practice these are rarely seen. • Pyuria suggests infection, but infection can occur in the absence of pyuria; • Conversely, pyuria can be present without UTI:

Sterile pyuria (positive leukocytes, negative culture) • • • • Partially Treated Bacterial Uti, Viral Infections, Urolithiasis, Renal Tuberculosis, Renal Abscess, UTI In The Presence Of Urinary Obstruction, Urethritis As A Consequence Of A Sexually Transmitted Infection Inflammation Near The Ureter Or Bladder (Appendicitis, Crohn Disease), Kawasaki Disease, Schistosomiasis, Neoplasm, Renal Transplant Rejection, Or Interstitial Nephritis (Eosinophils).

Leukocyte esterase • A surrogate marker of pyuria, has sensitivity of 79% and specificity of 87% for UTIs

Bacteria • Sensevity : 81% • Specifity: 83%

The nitrite dipstick test • The nitrite dipstick test represents the conversion of dietary nitrate by Gram-negative bacteria, and has high specificity (98%) for UTI • Its major limitation is that it gives negative results when the bladder is emptied frequently or if the underlying pathogen is Gram-positive

Microscopic hematuria • is common in acute cystitis, but microhematuria alone does not suggest UTI.

NELSON

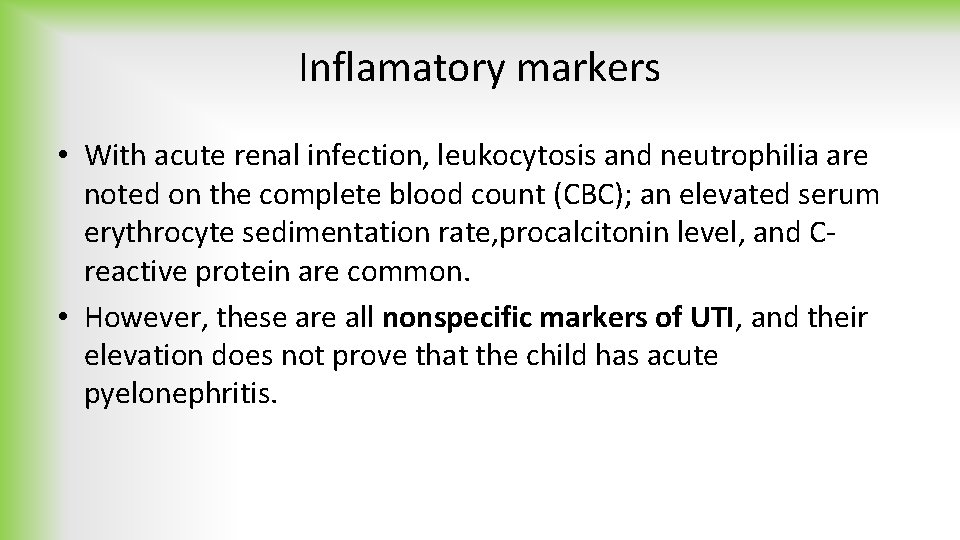

Inflamatory markers • With acute renal infection, leukocytosis and neutrophilia are noted on the complete blood count (CBC); an elevated serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate, procalcitonin level, and Creactive protein are common. • However, these are all nonspecific markers of UTI, and their elevation does not prove that the child has acute pyelonephritis.

BLOOD CULTURE • Bacteremia in the setting of pyelonephritis is reported to occur in 3– 20% of patients and is most common in infants less than 90 days old and in any child with obstructive uropathy. • For these high-risk groups, particularly if the patient appears to be ill at presentation, blood cultures should be drawn before starting antibiotics, if possible.

Asymptomatic Bacteriuria • Children with positive urine culture and normal urinalysis, without symptoms, are regarded as having asymptomatic bacteriuria that, in otherwise healthy subjects, is not an indication for any intervention.

Conclusions • Urine tests should be performed before administration of antimicrobials. In toilet-trained children, a clean voided midstream urine sample is the method of choice for diagnosing a UTI, while catheterization is a preferred invasive method of urine sampling in infants and small children. • Urine sample collected in a bag applied to the perineum can be used as a UTI exclusion method. • Both positive urinalysis and significant bacteriuria are necessary to diagnose a UTI. • Children with positive urine culture and negative urinalysis, without symptoms, are regarded as having asymptomatic bacteriuria, which, in otherwise healthy subjects is not an indication for any intervention. • It is recommended that the diagnosis of a UTI be dependent on the urine collection method, and that it is defined by significant bacteriuria as >10000 CFU/ml in clean voided urine with symptoms and as >100000 and abnormal urinalysis without symptom , 50000 CFU/ml and any growth of bacteria by SPA.

Reference • • Review Article Urinary tract infection in children: Diagnosis, treatment, imaging e: Comparison of current guidelines. M. Okarska-Napierała a, A. Wasilewska b, E. Kuchar. Journal of Pediatric Urology (2017) 13, Matthijs Oyaert, M. Sc. , and Joris Delanghe Progress in Automated Urinalysis , Ann Lab Med 2019; 39: 15 -22 E. Cousin a, *, A. Ryckewaert a, C. de Jorna Lecouvey a, b, A. P. Arnaud c, Urine collection methods used for non-toilet-trained children in pediatric emergency departments in France: A medical practice analysis , Archives de Pe´ diatrie 26 (2019) 16– 20 S. J. M. Middelkoop, BSc a, �, L. J. van Pelt, ET AL, Routine tests and automated urinalysis in patients with suspected urinary tract infection at the ED, American Journal of Emergency Medicine 34 (2016) 1528– 1534

Thanks for your attention

Nursing management for urinary tract infection

Nursing management for urinary tract infection Urinary tract infection

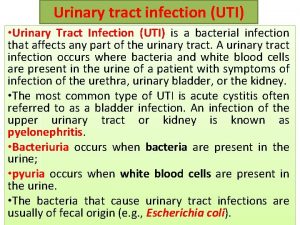

Urinary tract infection Symptoms of urinary tract infection

Symptoms of urinary tract infection Complicated urinary tract infection

Complicated urinary tract infection Urinary tract infection in pregnancy ppt

Urinary tract infection in pregnancy ppt Tumor in the urinary tract

Tumor in the urinary tract Urinary tract obstruction

Urinary tract obstruction Urinary bladder

Urinary bladder Sexually transmitted diseases

Sexually transmitted diseases Classification of upper respiratory tract infection

Classification of upper respiratory tract infection Conclusion of respiratory tract infection

Conclusion of respiratory tract infection Pyramidal vs extrapyramidal

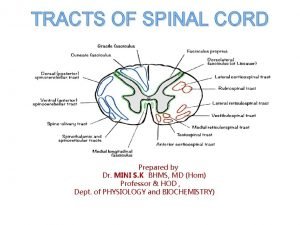

Pyramidal vs extrapyramidal Anterior spinothalamic tract

Anterior spinothalamic tract Medical diagnosis and nursing diagnosis difference

Medical diagnosis and nursing diagnosis difference Medical diagnosis and nursing diagnosis difference

Medical diagnosis and nursing diagnosis difference Medical diagnosis and nursing diagnosis difference

Medical diagnosis and nursing diagnosis difference Perbedaan diagnosis gizi dan diagnosis medis

Perbedaan diagnosis gizi dan diagnosis medis Step of nursing process

Step of nursing process Ziarat fatima zahra

Ziarat fatima zahra Zahra mixes 150g of metal a

Zahra mixes 150g of metal a Bibi zehra ye dua hai

Bibi zehra ye dua hai Ummul masaib zahra lyrics

Ummul masaib zahra lyrics Zahra aivazpour

Zahra aivazpour Zahra kavehvash

Zahra kavehvash Mensturation

Mensturation Zahra ki betiyon lyrics

Zahra ki betiyon lyrics Negotiation

Negotiation Zahra literacy shed

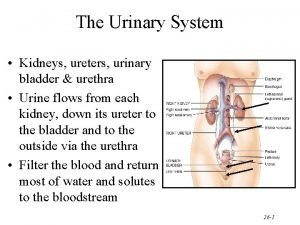

Zahra literacy shed The urinary system chapter 15

The urinary system chapter 15 Rat urinary system

Rat urinary system Fundus of bladder

Fundus of bladder Micturition

Micturition Anatomical structure of urinary system

Anatomical structure of urinary system Epithelial component

Epithelial component Urinary structure

Urinary structure Urinary bladder

Urinary bladder