Upper cervical injury classification systems A summary Presenters

- Slides: 42

Upper cervical injury classification systems A summary Presenter‘s name Arial 24 pt Meeting Arial 24 pt Presenter‘s title Arial 20 pt City, Month, Year Arial 20 pt

Learning outcomes • Identify the clinical and radiological findings associated with upper cervical fractures • Recognize the different injuries in the C 0– 2 segment • Classify each fracture and correlate with the situation of mechanical stability

High cervical anatomy • Biomechanically specialized • Support for cranial mass • Considerable ROM versus great stability • 50% cervical flexion/extension occurs at C 0– 1 • 50% cervical rotation occurs at C 1– 2 • Unique osteoligamentous characteristics • Powerful static stabilizers • 3 -joint complex

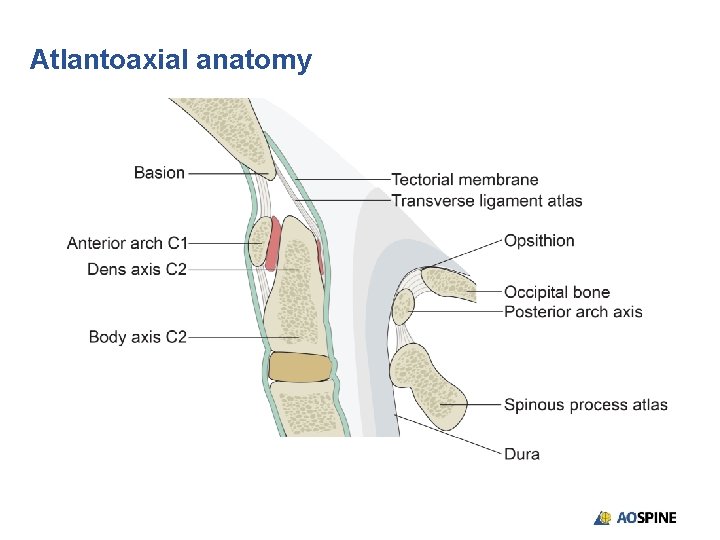

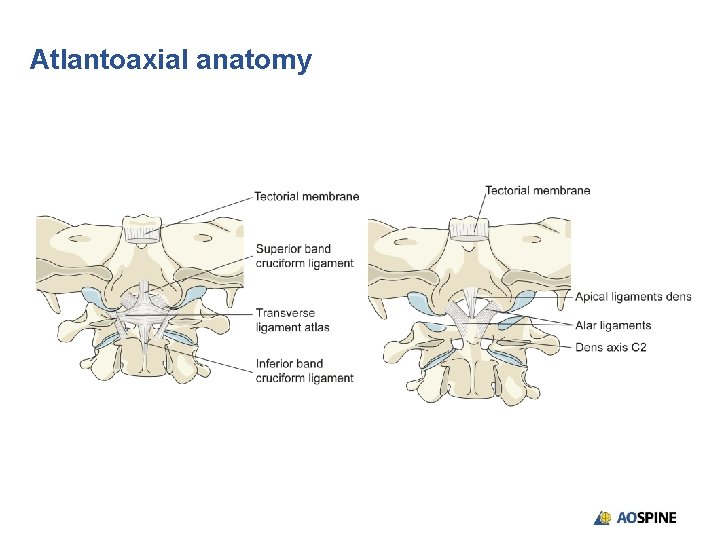

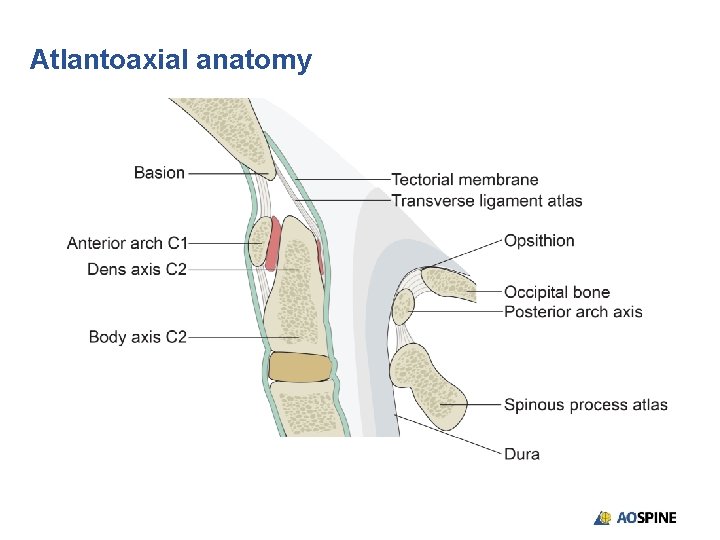

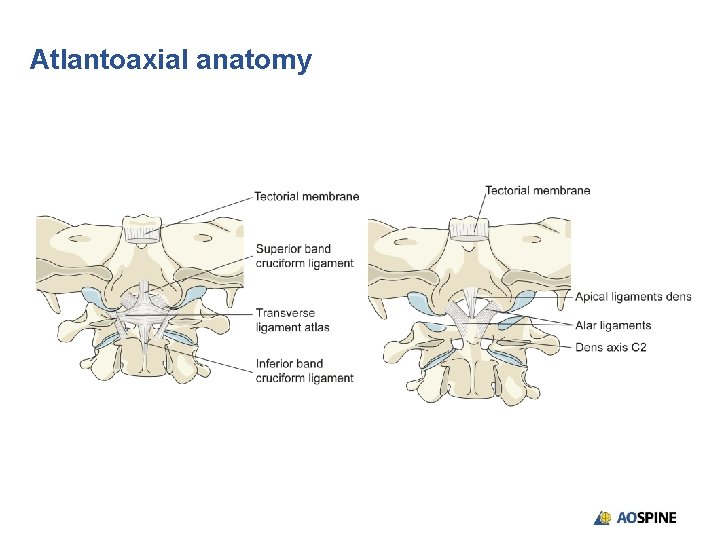

Atlantoaxial anatomy

Atlantoaxial anatomy

Upper cervical spinal injuries • Possible lesions • Occipital-cervical dissociation • Occipital condyle fractures • C 1 arch fracture • Odontoid fractures • C 2 traumatic spondylolisthesis

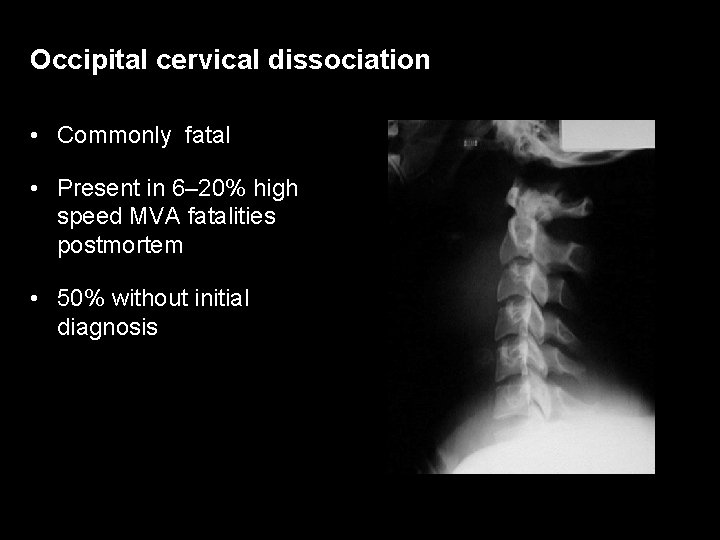

Occipital cervical dissociation • Commonly fatal • Present in 6– 20% high speed MVA fatalities postmortem • 50% without initial diagnosis

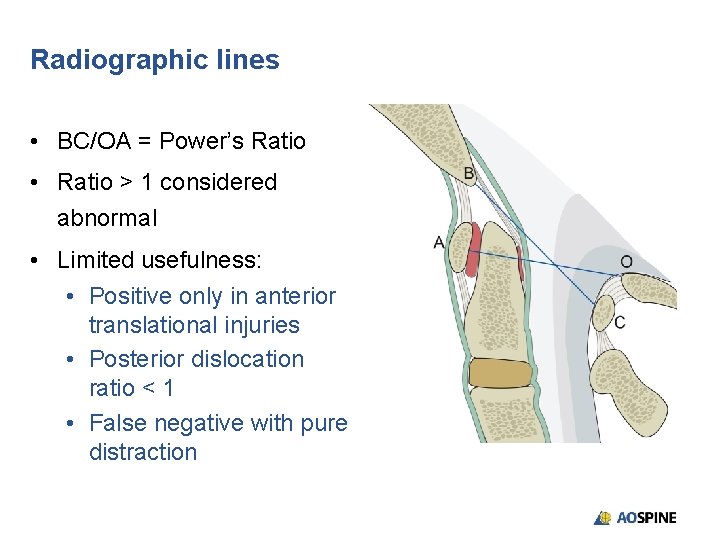

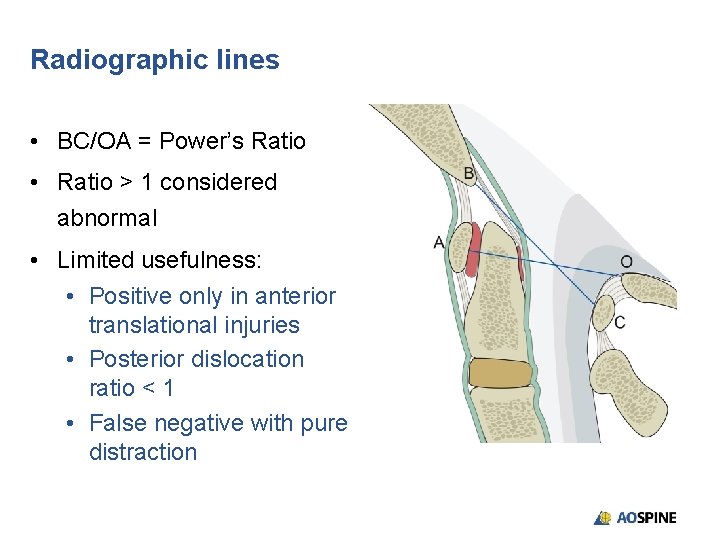

Radiographic lines • BC/OA = Power’s Ratio • Ratio > 1 considered abnormal • Limited usefulness: • Positive only in anterior translational injuries • Posterior dislocation ratio < 1 • False negative with pure distraction

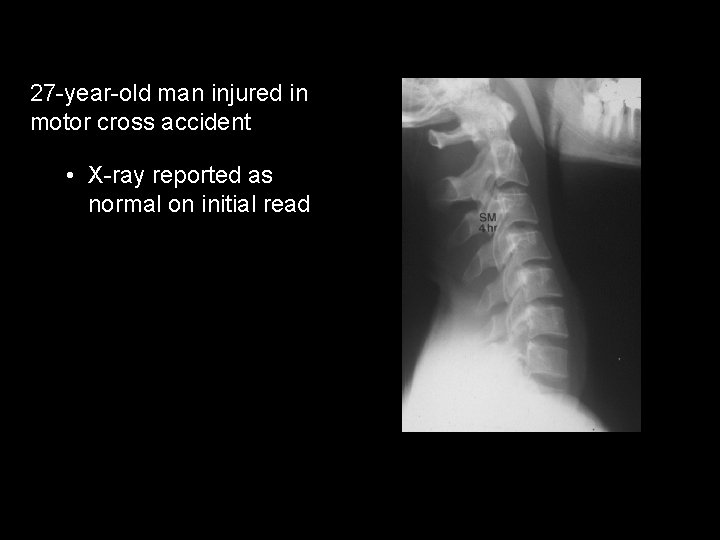

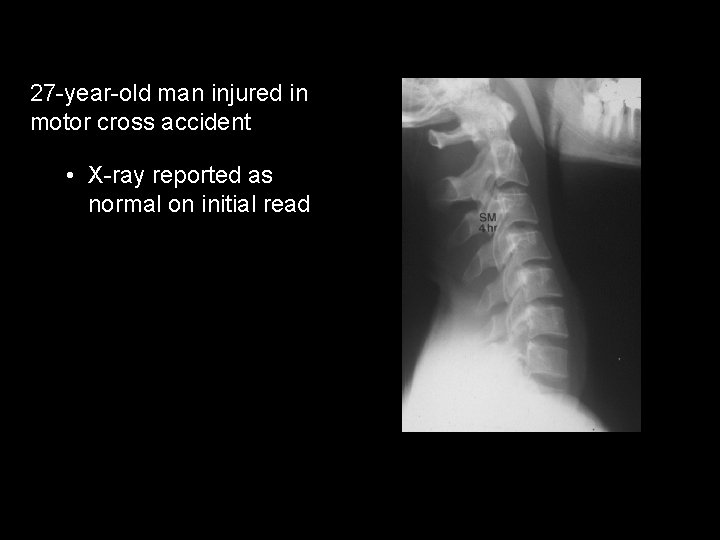

27 -year-old man injured in motor cross accident • X-ray reported as normal on initial read

27 -year-old man injured in motor cross accident • Prevertebral edema C 1 – 2 • Should be < 6 mm in front of C 2 • Rotational subluxation C 1– 2

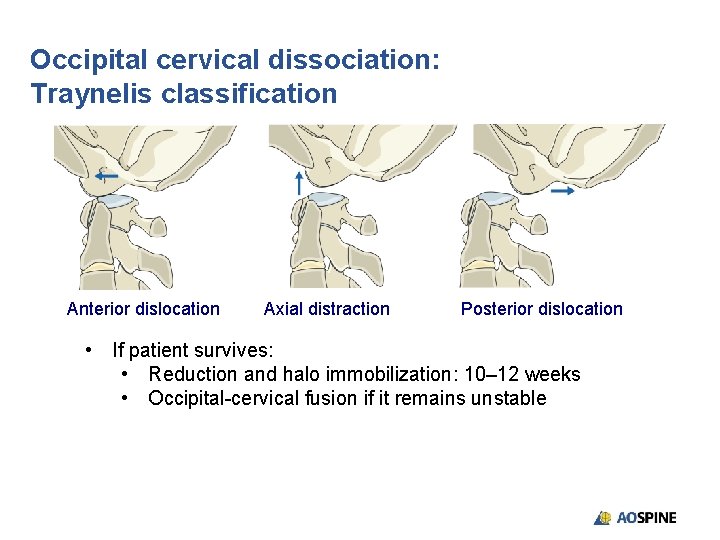

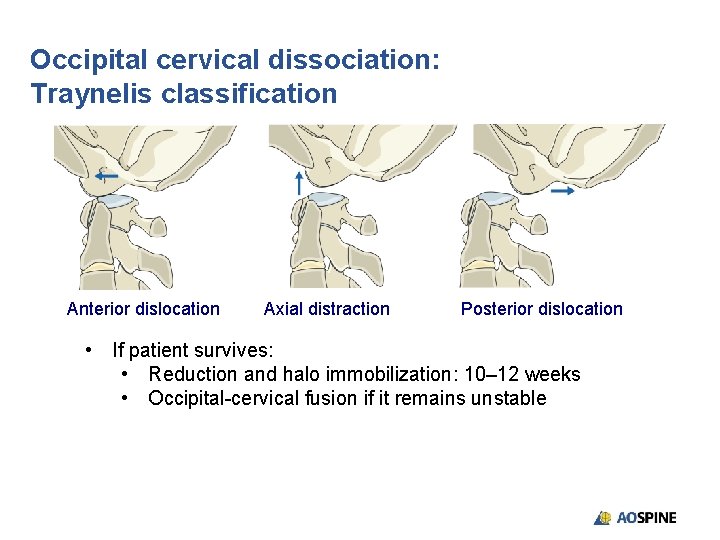

Occipital cervical dissociation: Traynelis classification Anterior dislocation Axial distraction Posterior dislocation • If patient survives: • Reduction and halo immobilization: 10– 12 weeks • Occipital-cervical fusion if it remains unstable

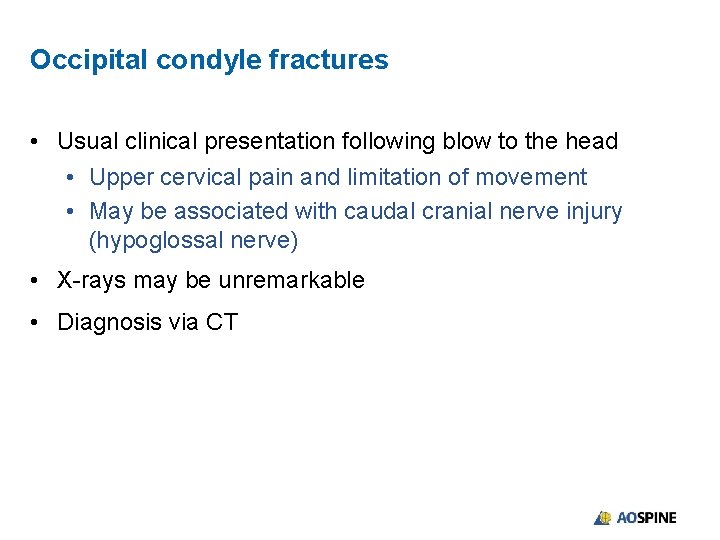

Occipital condyle fractures • Usual clinical presentation following blow to the head • Upper cervical pain and limitation of movement • May be associated with caudal cranial nerve injury (hypoglossal nerve) • X-rays may be unremarkable • Diagnosis via CT

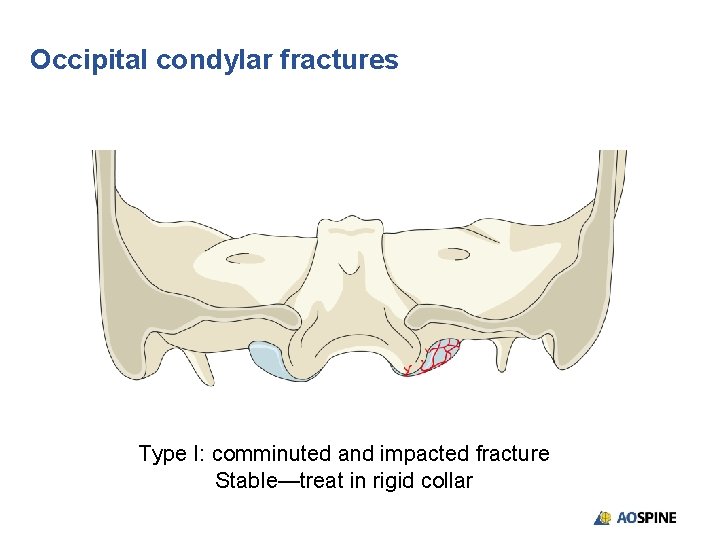

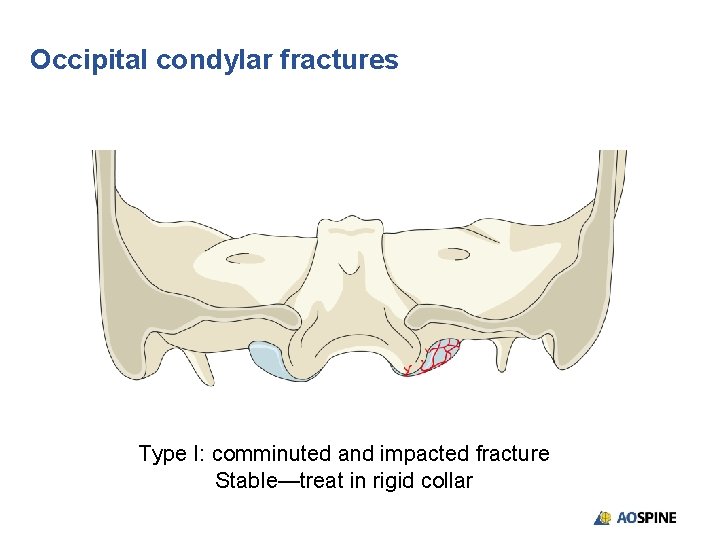

Occipital condylar fractures Type I: comminuted and impacted fracture Stable—treat in rigid collar

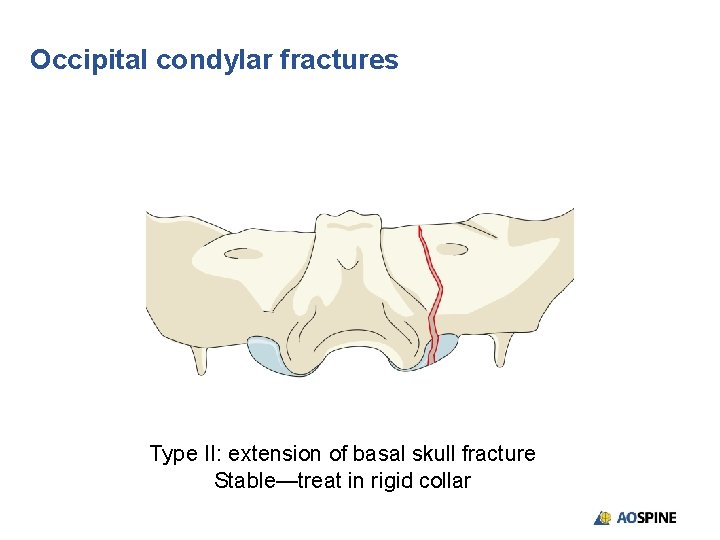

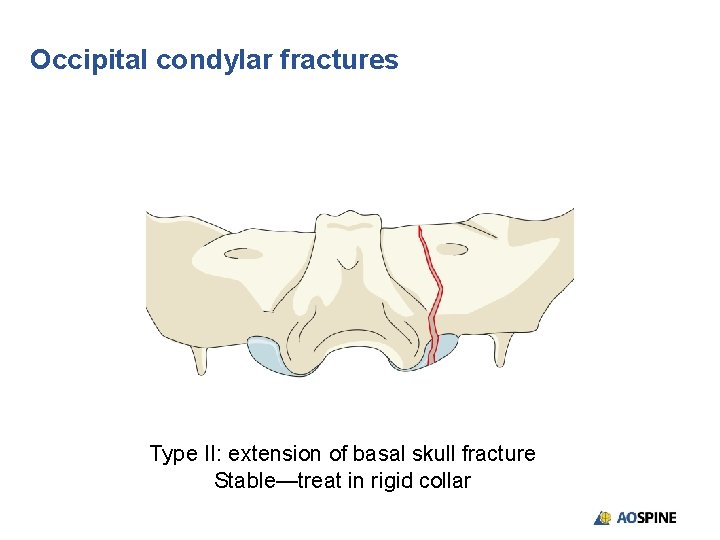

Occipital condylar fractures Type II: extension of basal skull fracture Stable—treat in rigid collar

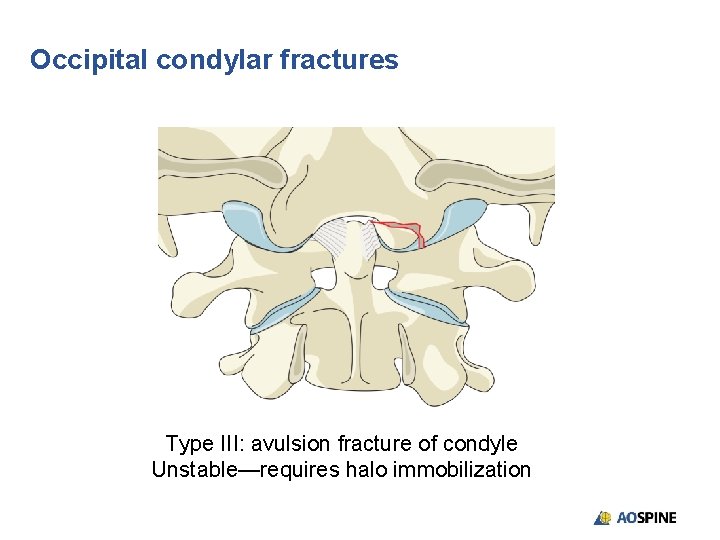

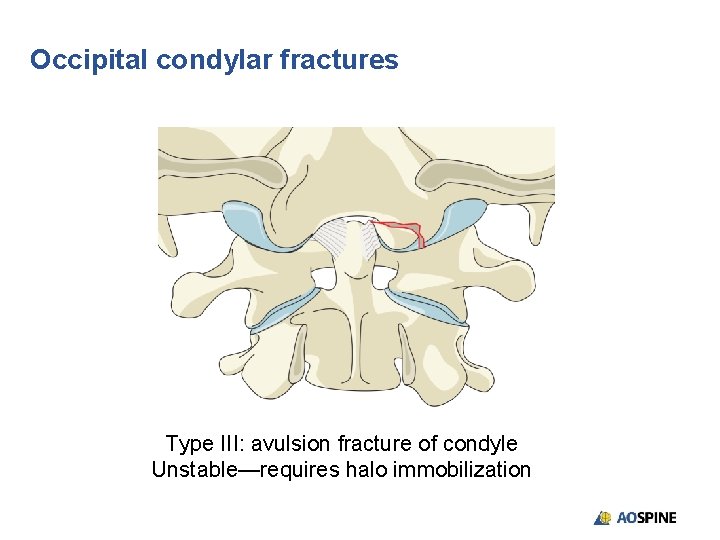

Occipital condylar fractures Type III: avulsion fracture of condyle Unstable—requires halo immobilization

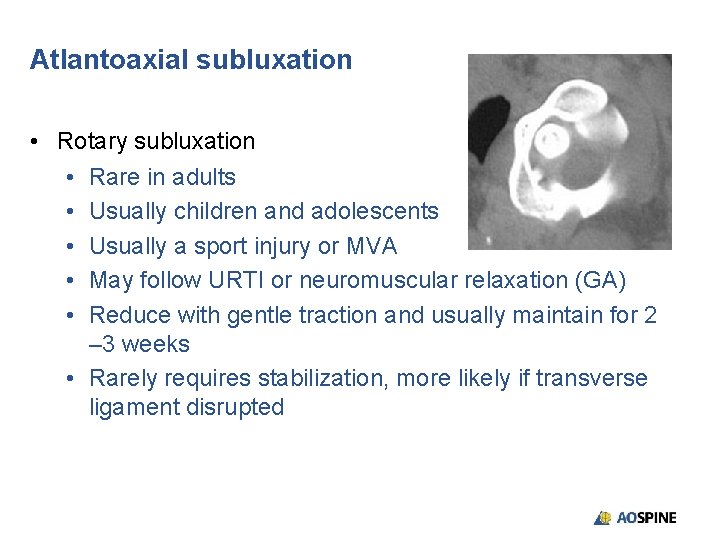

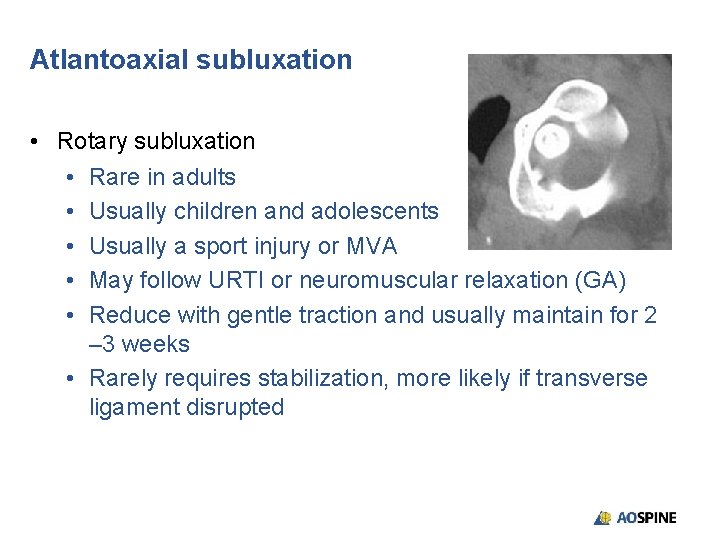

Atlantoaxial subluxation • Rotary subluxation • Rare in adults • Usually children and adolescents • Usually a sport injury or MVA • May follow URTI or neuromuscular relaxation (GA) • Reduce with gentle traction and usually maintain for 2 – 3 weeks • Rarely requires stabilization, more likely if transverse ligament disrupted

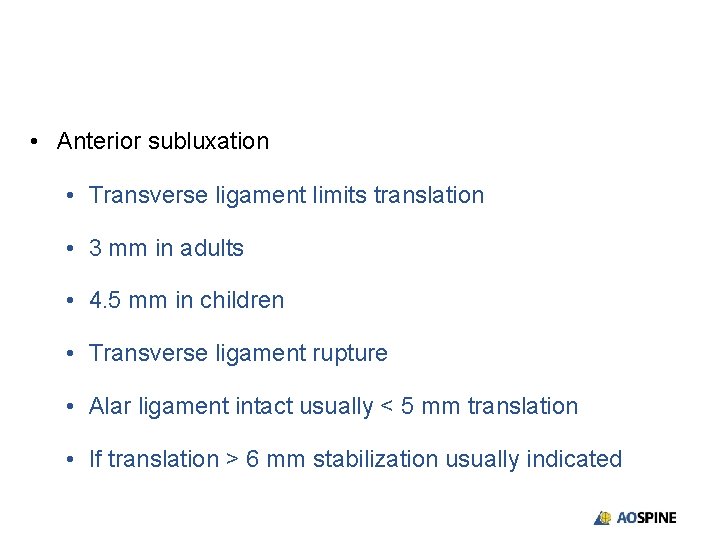

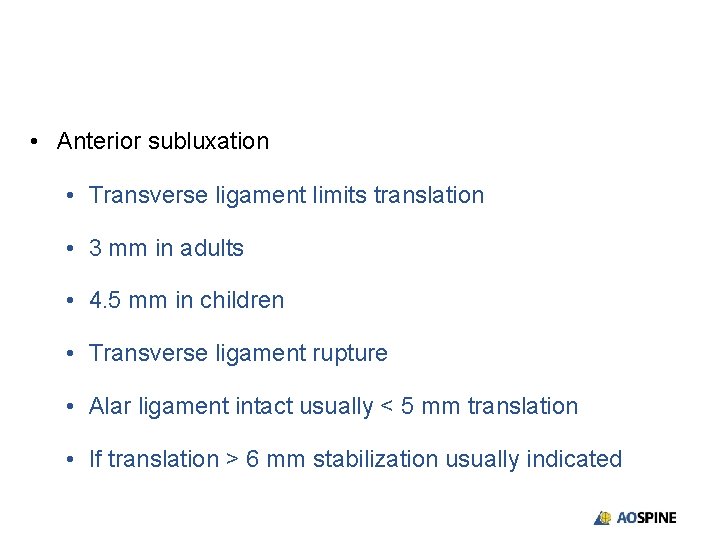

• Anterior subluxation • Transverse ligament limits translation • 3 mm in adults • 4. 5 mm in children • Transverse ligament rupture • Alar ligament intact usually < 5 mm translation • If translation > 6 mm stabilization usually indicated

C 1 arch fractures • 2% of the cervical lesions • Nonspecific symptomatology • Diagnosis: x-ray, CT, MRI • Isolated posterior arch fracture • Lateral mass fracture • Jefferson fracture (Burst) • Stability related to integrity of transverse ligament

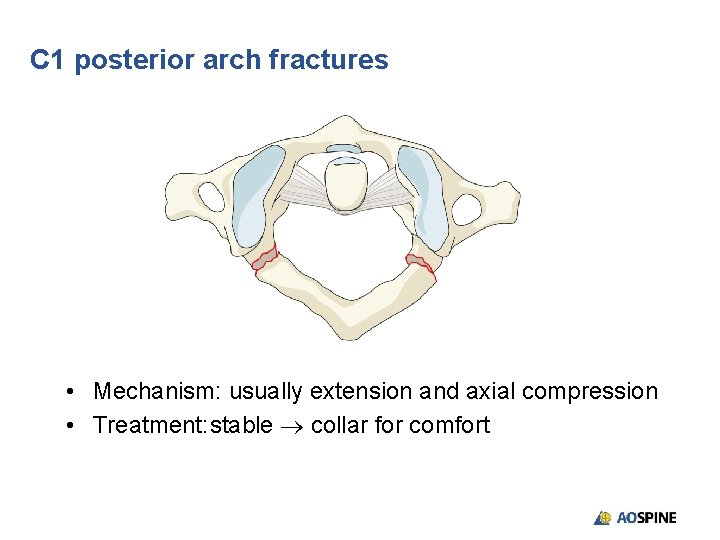

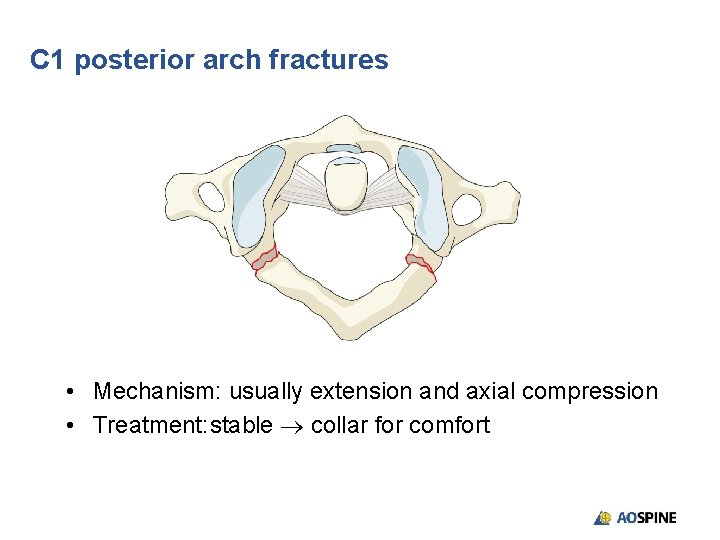

C 1 posterior arch fractures • Mechanism: usually extension and axial compression • Treatment: stable collar for comfort

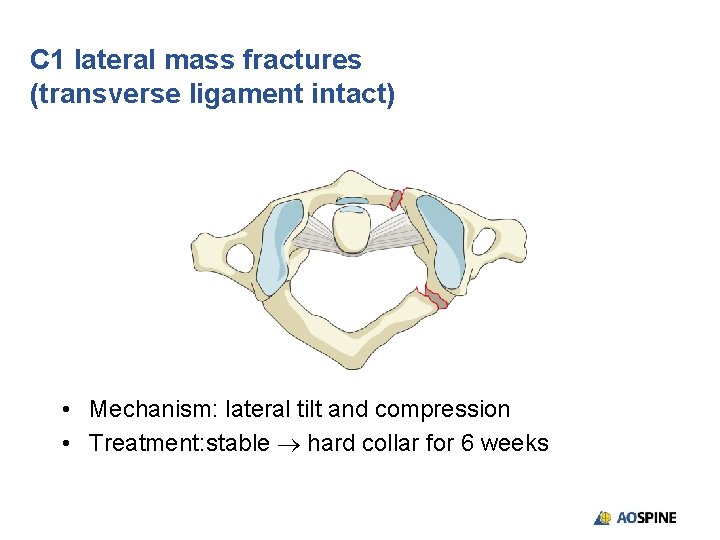

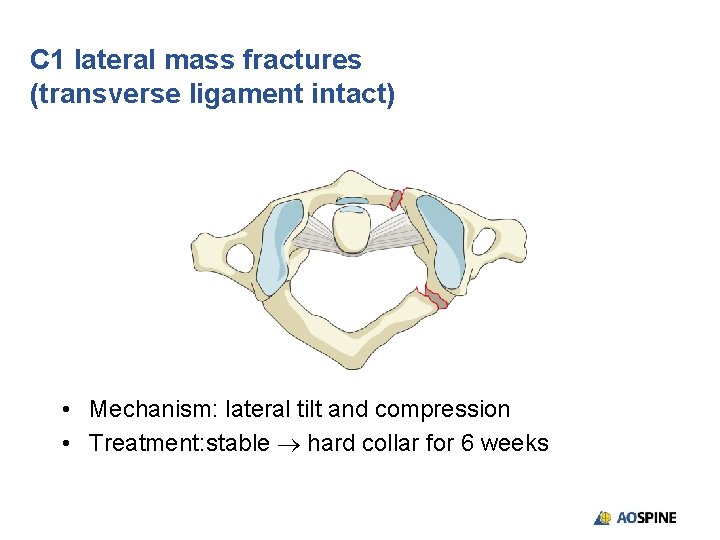

C 1 lateral mass fractures (transverse ligament intact) • Mechanism: lateral tilt and compression • Treatment: stable hard collar for 6 weeks

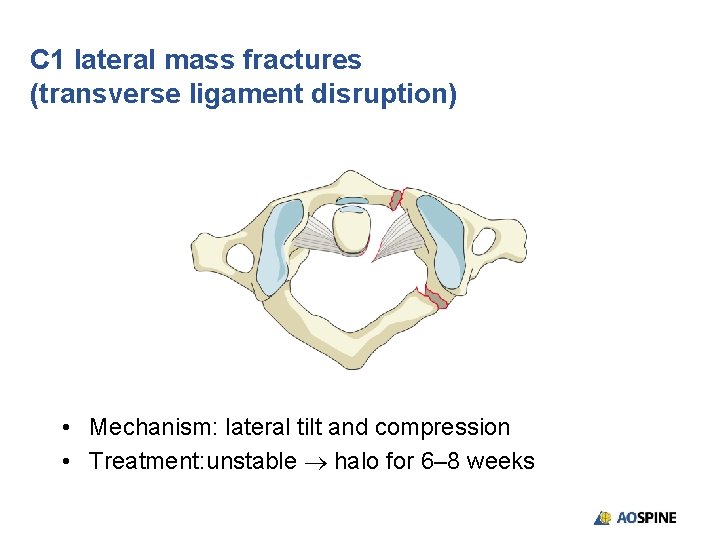

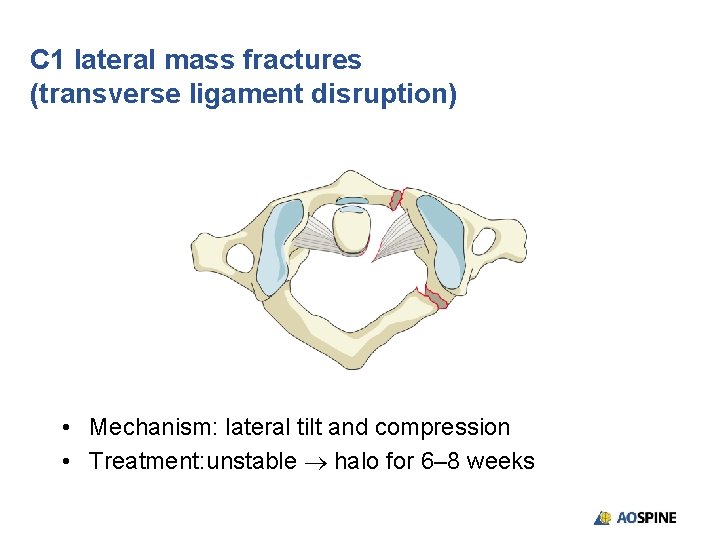

C 1 lateral mass fractures (transverse ligament disruption) • Mechanism: lateral tilt and compression • Treatment: unstable halo for 6– 8 weeks

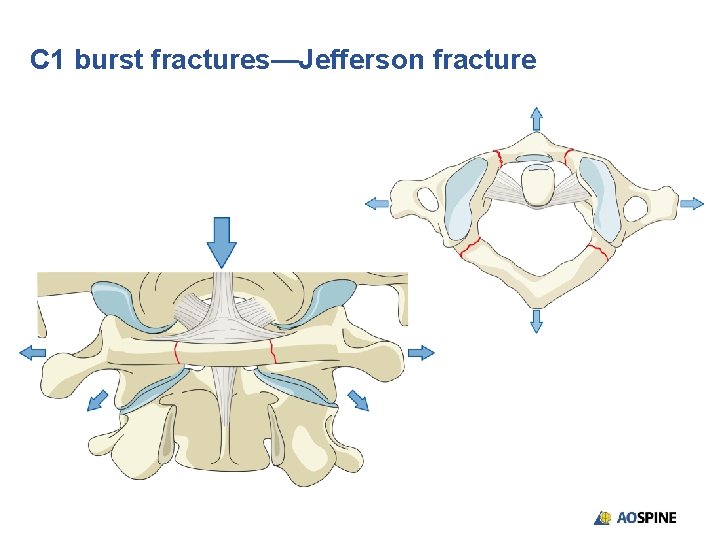

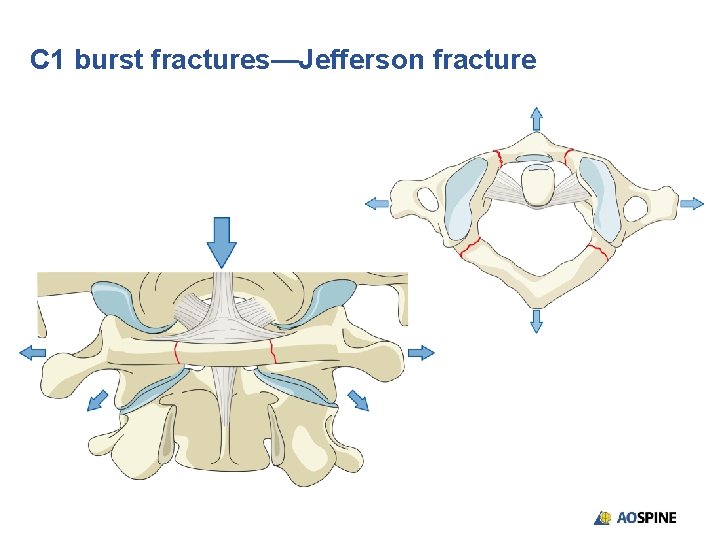

C 1 burst fractures—Jefferson fracture

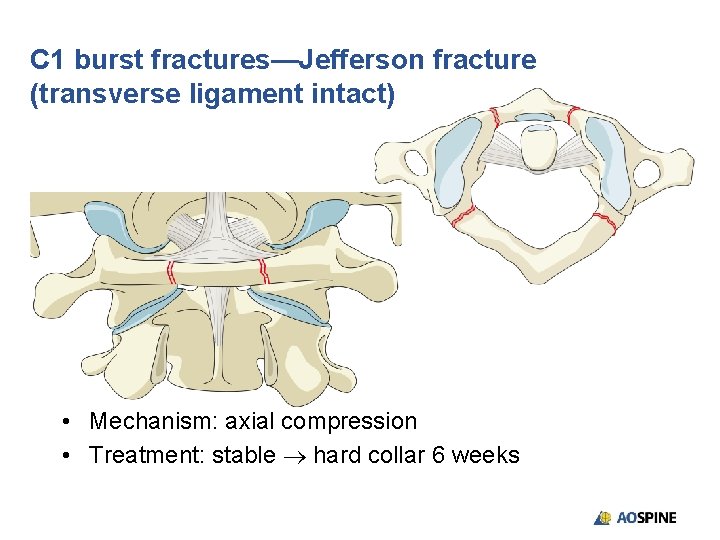

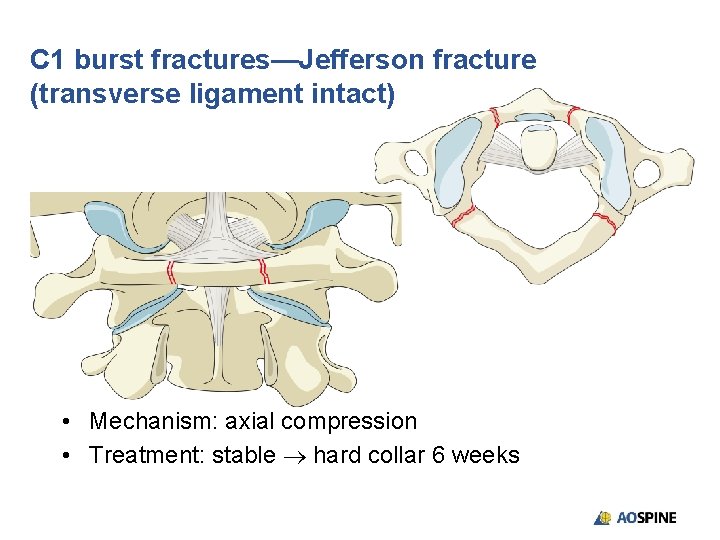

C 1 burst fractures—Jefferson fracture (transverse ligament intact) • Mechanism: axial compression • Treatment: stable hard collar 6 weeks

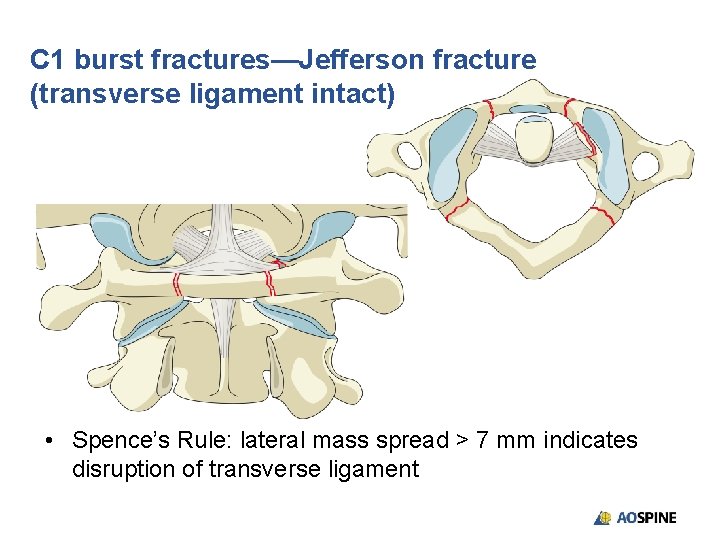

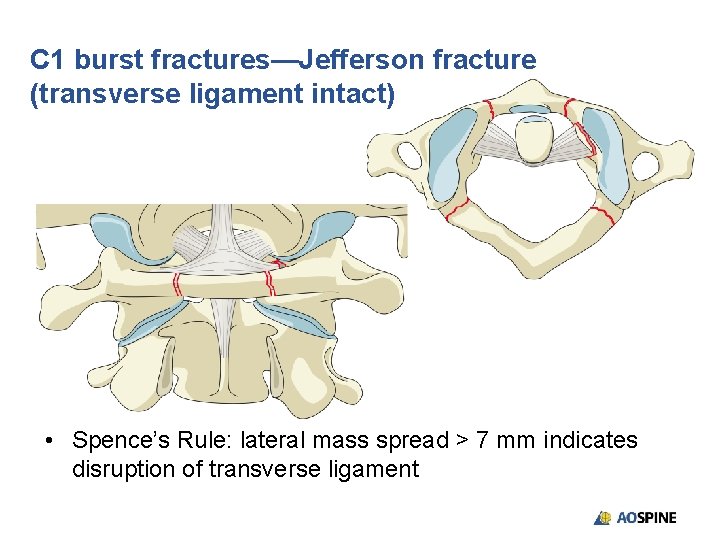

C 1 burst fractures—Jefferson fracture (transverse ligament intact) • Spence’s Rule: lateral mass spread > 7 mm indicates disruption of transverse ligament

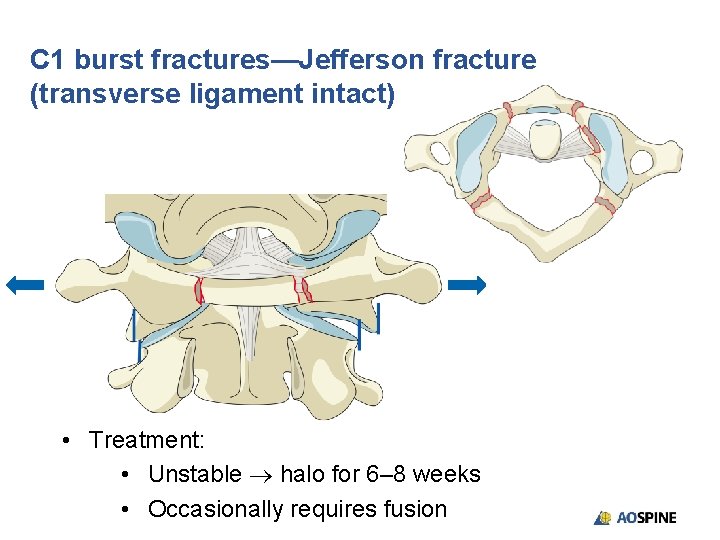

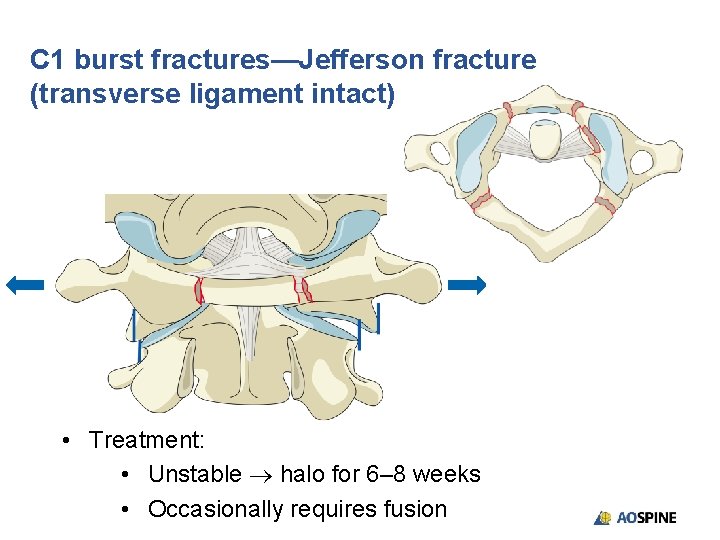

C 1 burst fractures—Jefferson fracture (transverse ligament intact) • Treatment: • Unstable halo for 6– 8 weeks • Occasionally requires fusion

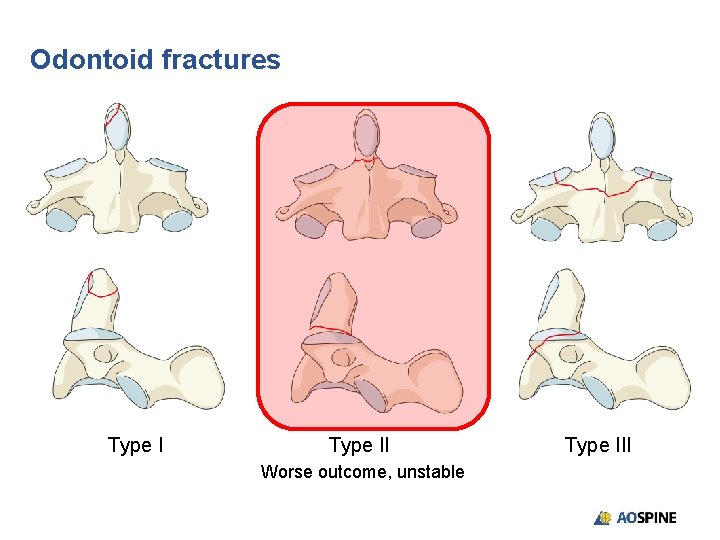

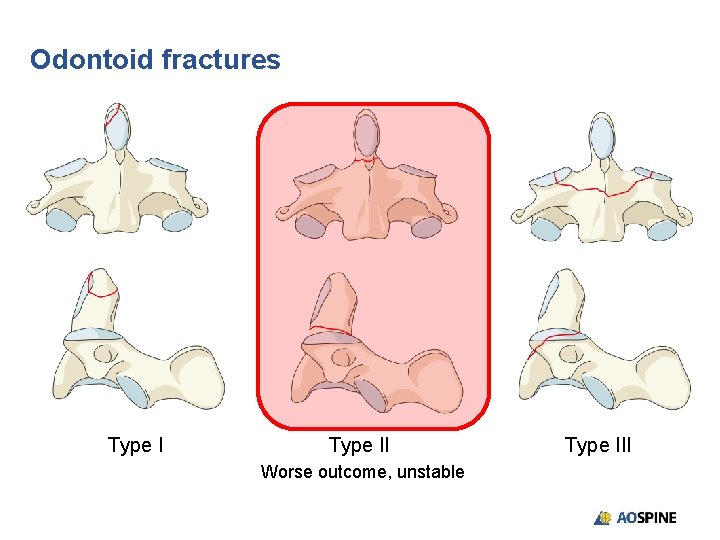

Odontoid fractures Type II Worse outcome, unstable Type III

Odontoid fractures Type I • Avulsion fracture of alar ligament • Stable high rate of fusion

Odontoid fractures Type II • Fracture at base of odontoid process • Unstable: high rate of nonunion • If < 6 mm and < 60 years old, 5– 10% nonunion • If < 6 mm and > 60 years old, 10– 15% nonunion • If > 6 mm and < 60 years old, 75% nonunion • If > 6 mm and > 60 years old, 85% nonunion • If there is a high risk of nonunion, consider stabilization • Nonunion often asymptomatic in elderly

Odontoid fractures Type III • Fracture of body of C 2 • Stable: halo immobilization • High rate of union

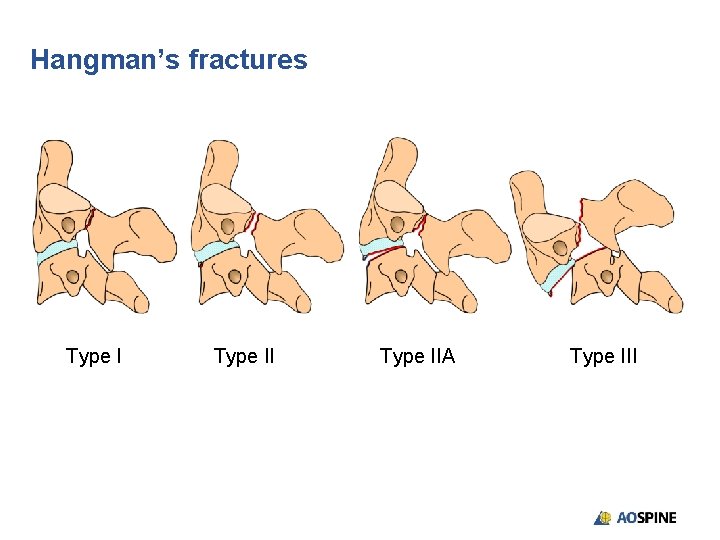

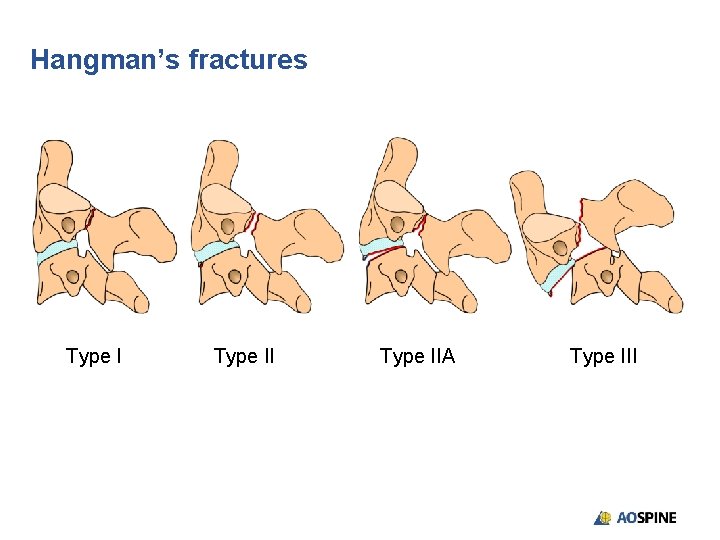

Hangman’s fractures Type IIA Type III

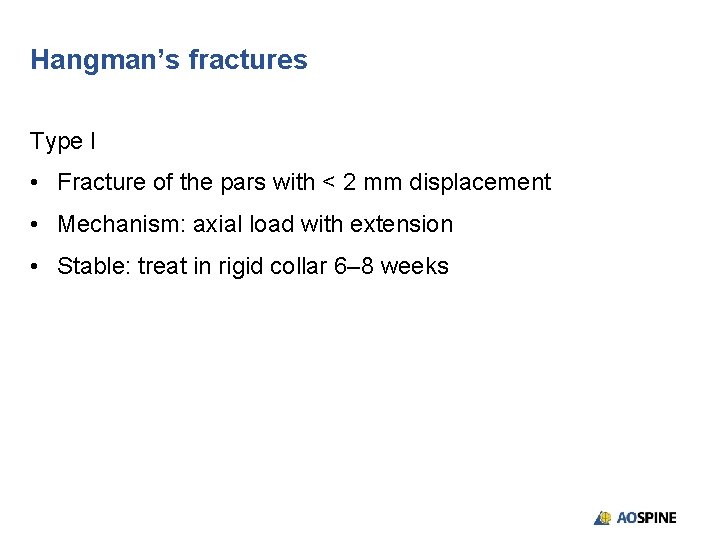

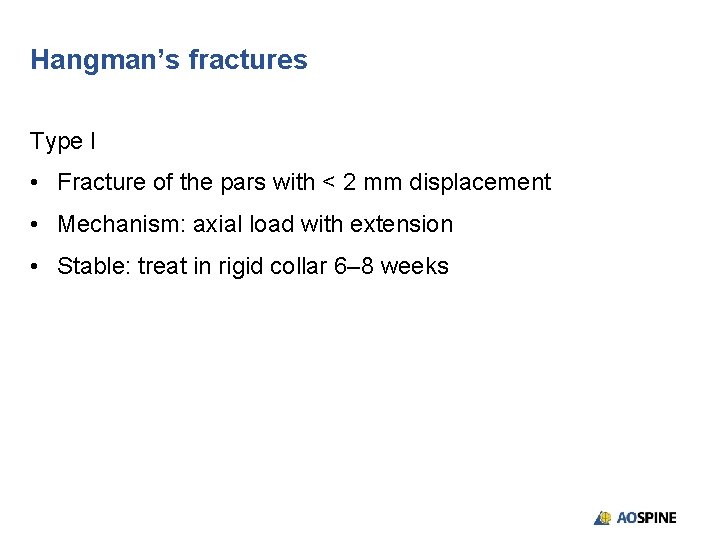

Hangman’s fractures Type I • Fracture of the pars with < 2 mm displacement • Mechanism: axial load with extension • Stable: treat in rigid collar 6– 8 weeks

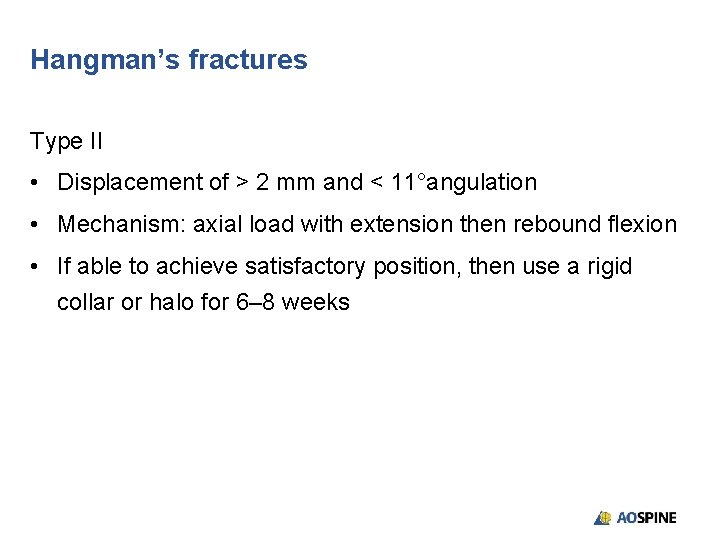

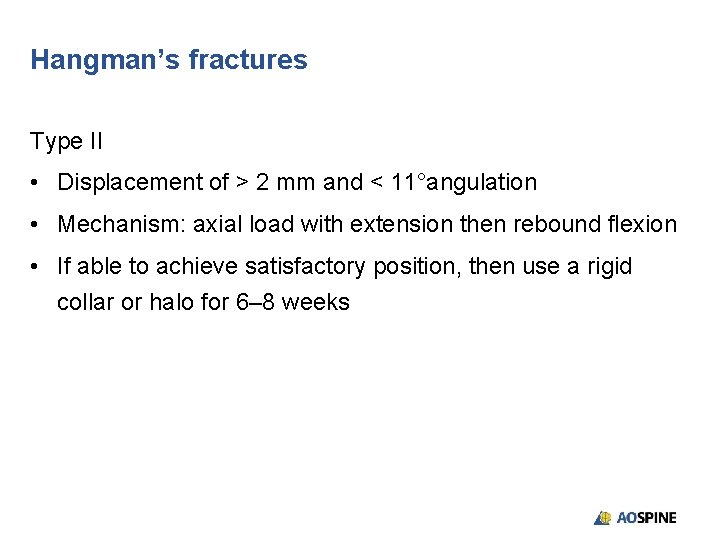

Hangman’s fractures Type II • Displacement of > 2 mm and < 11°angulation • Mechanism: axial load with extension then rebound flexion • If able to achieve satisfactory position, then use a rigid collar or halo for 6– 8 weeks

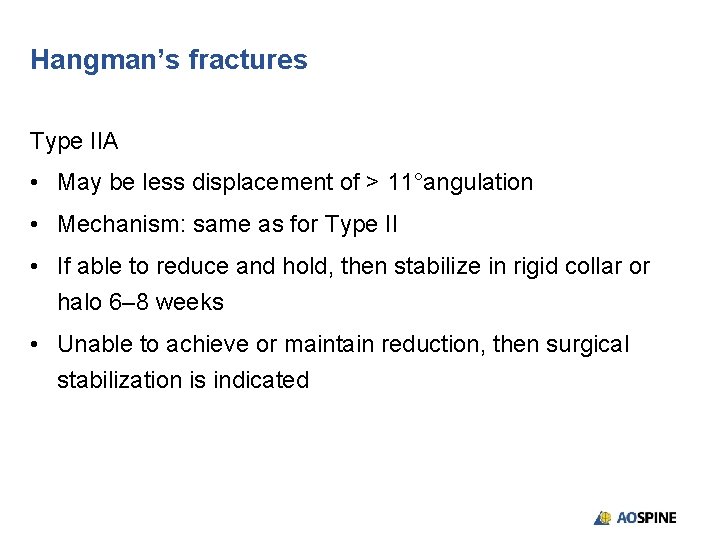

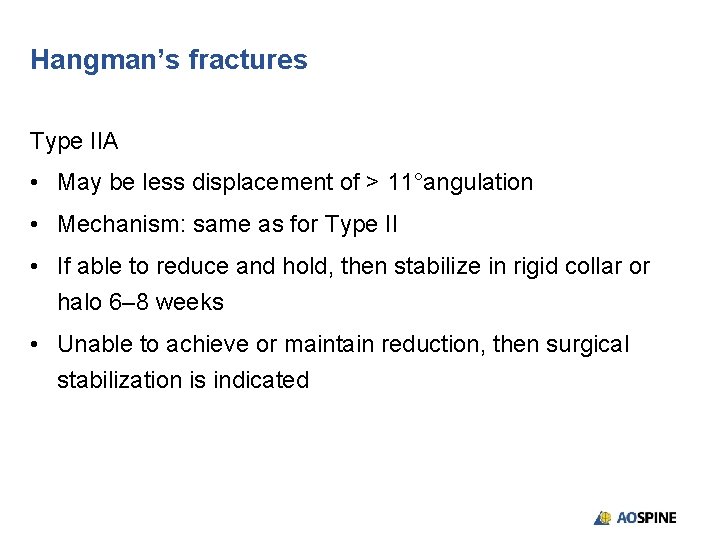

Hangman’s fractures Type IIA • May be less displacement of > 11°angulation • Mechanism: same as for Type II • If able to reduce and hold, then stabilize in rigid collar or halo 6– 8 weeks • Unable to achieve or maintain reduction, then surgical stabilization is indicated

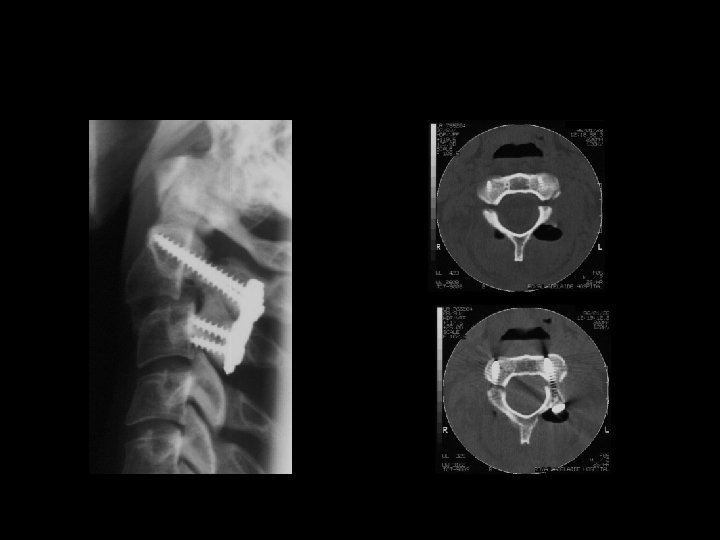

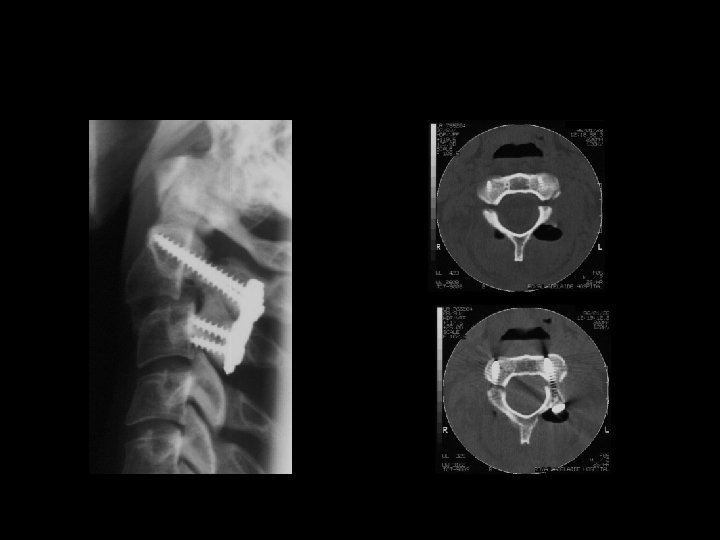

Hangman’s fractures Type III • Disruption of C 2/3 facet joint leading to listhesis • Mechanism: compression and flexion • This is an unstable injury and requires reduction and stabilization

Take-home messages • Severe upper cervical injuries are often missed on routine imaging • Due to unique anatomical and biomechanical features several different injury patterns and classifications are utilized • Have a high index of suspicion • Stability of the injury will determine the appropriate management, bracing, or surgical stabilization

Excellence in Spine