UPDATE ON DELIRIUM IN PALLIATIVE AND HOSPICE CARE

- Slides: 38

UPDATE ON DELIRIUM IN PALLIATIVE AND HOSPICE CARE LINDA GANZINI, MD, MPH Associate Director, HSR&D Center of Innovation, Portland VA Health Care System Professor of Medicine and Psychiatry, Oregon Health & Science University

What is Delirium? Delirium is a transient organic mental syndrome of acute onset, characterized by global impairment of cognitive function, a reduced level of consciousness, attention abnormalities, increased or decreased psychomotor activity, and disordered sleepwake cycle. • In DSM-5, primarily a disorder of attention, awareness and cognition • In DSM 4 -level of consciousness was of primary importance over awareness.

Terms Used/Misused to Denote Delirium • Acute brain failure • Confusional state • Acute brain syndrome • ICU psychosis • Acute confusional state • Metabolic • Acute organic brain syndrome • Organic brain syndrome • Cerebral insufficiency encephalopathy • Toxic encephalopathy • Terminal agitation • Terminal restlessness • Altered mental status

Delirium—why important • Remains underrecognized • Preventable condition in 30 -40% of cases • Costly--$160 billion year in US. • Leads to a variety of potentially morbid outcomes • Multiple patient safety issues • Highly distressing for patients and their supports • Most common reasons for palliative sedation at the end of life. Inouye, Lancet Psychiatry 2014, Schur BMC Palliative Care, 2016, Mercanti JPSM 2012; Omalley, Finucane, Psychology, 2017; de la Cruz, Support Care Cancer, 2015

Epidemiology • 1 -2% of community living elderly • 14 -56% of hospitalized elderly • 70 -87% of elderly in ICU • 28 -42% on admission to palliative care unit • 90% in cancer patients in last weeks of life (Lawlor, Arch Inter Med, 2000, Inouye, Lancet Psychiatry, 2014)

Adverse outcomes • Increased mortality (1. 5 -4 fold depending on setting) • Extended cognitive impairment following episode of delirium • Increased physical function impairment for 30 days after discharge • Higher rates of institutionalization Inouye, Lancet Psychiatry, 2014

Clinical Features of Delirium Prodrome Restlessness, anxiety, sleep disturbance, irritability Attention decreased (easily distractible) Altered arousal and psychomotor abnormality Sleep-wake disturbance (usually worsens at night) Impaired memory (can’t register new information) Disorganized thinking and speech Disorientation—time, place, person Perceptions altered—misperceptions, illusions, delusions (poorly formed), hallucinations • Emotional lability • •

Attention • Normal Able to mobilize, direct, focus, sustain, and shift attention voluntarily and intentionally • Measures at the bedside • Days of week backward--0 errors • Months of year backward--not more than one error

Arousal Waxing and waning of level of consciousness with periods of lethargy/somnolence is common, but not necessary for the diagnosis

Sleep • Fragmented sleep/wake cycle • Nighttime awakenings • Often first signs of delirium at night • Delirium may be worse at night, but some studies show morning worsening

Delirium Subtypes: Hypomotoric • “Quiet” delirium • Patients appear lethargic, listless, apathetic • Has worse prognosis than hyperactive form • Patients often perceived as depressed • Often overlooked, permissively approached, even normalized in palliative and hospice care • Most common form in palliative care settings • Can change to hyperactive form

Hyperactive Delirium • Patients vigilant, restless, loud, irritable, agitated • Called “terminal restlessness” or “ terminal agitation” in palliative care • Associated with increased self-harm, caregiver burden and distress, need for hospital admission from hospice • Hallmark of a “bad death”

Delirium –Qualitative Experience • Fear, anxiety, feeling threatened, shame, hopelessness • Dream like state with no control • Distress when cannot communicate with loved ones • Lability, tearfulness, anger • For those who remember delirium, high degrees of distress-fear of delirium returning, embarrassment, remorse. • Visual hallucinations, delusions and misinterpretations— lead to anxiety and fear • Family members—very distressed, wanted more explanation about delirium. • O’Malley, J Psych Research, 2008; Finucane Psychooncology, 2017

Delirium is Very Distressing for Patients and Caregivers • 154 patients with cancer and delirium • 53% recalled delirium • Mean delirium-related distress on 0 -4 scale, was 3. 2 for patients, 3. 75 for spouses and caregivers • Delusions were the most predictive of patient distress • No difference in patient distress between hypoactive and hyperactive delirium • Low functional status was most predictive of caregiver distress Breitbart, et al Psychosomatics, 2002

Diagnosis • Confusion Assessment Method (CAM) - Acute on mental status changes plus inattention - Either disorganized thinking or change in level of consciousness -94% sensitive, 89% specific, improved with formal measures of cognition such as MOCA Requires moderate levels of some training Inouye, Lancet Psychiatry, 2014

Delirium Incidence and Outcomes in Advanced Cancer • Delirium is the most common mental disorder in dying cancer patients—occurs in 80 -90% before death • Delirium independently predicts death, even when functional status, weight loss and dyspnea are taken into account. • Relapsing/remitting course—half of patients with advanced cancer who develop delirium will improve significantly before death, many without intervention • Lawlor, Arch Inter Med, 2000

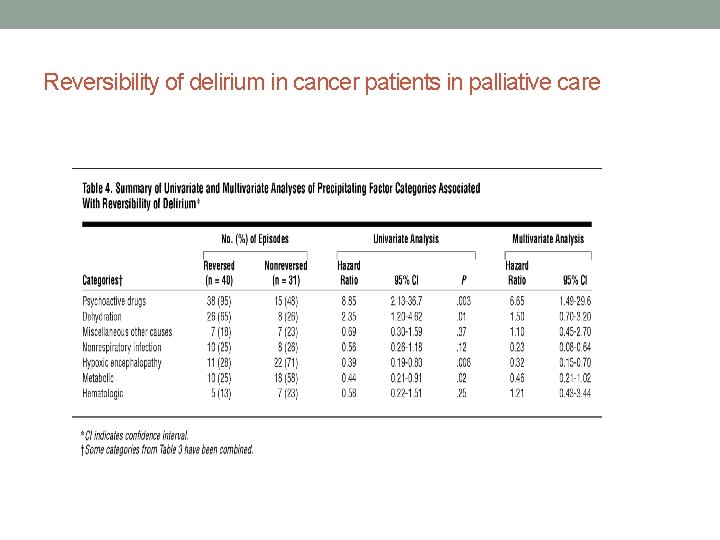

Reversibility of Delirium in Palliative Care • Initial deliria reversible in half of palliative care patients • Reversibility associated with psychoactive medications (particularly opiates) , dehydration, hypercalcemia • Nonreversible deliria associated with hypoxia and metabolic factors in univariate analyses, also nonrespiratory infections in multivariate analyses • Half the time no cause found Lawlor et al, Arch Int Medicine, 2000; Morita et al, JPSM, 2001; Bruera et al, 1992,

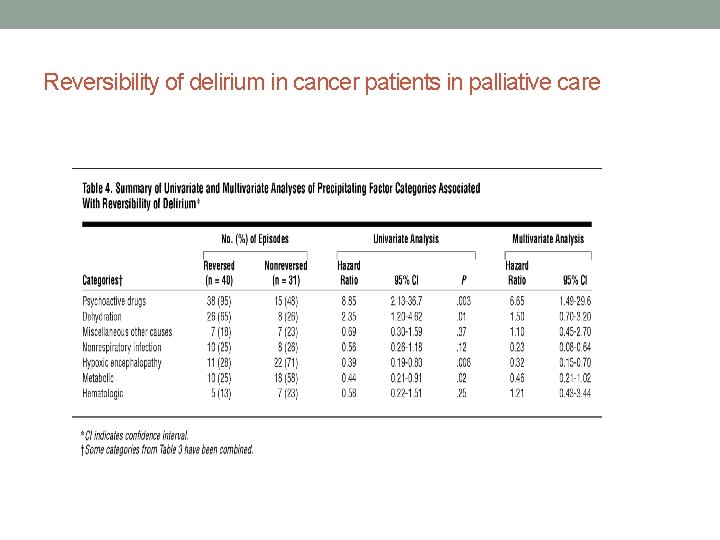

Reversibility of delirium in cancer patients in palliative care

Goals of Care • Awake, alert, calm, cognitively intact, able to communicate coherently with family and caregivers • Work-up of delirium must be balanced between likelihood of facilitating above and minimizing invasive or burdensome procedures and stress • Some normalization of quiet delirium in hospice—some palliative care clinicians see hallucinations and delusions of deceased relatives as an appropriate transition called “decathexis” Freidlander and Breitbart, Oncology, 2004

Risk factors for Delirium • Dementia or any cognitive impairment • Functional impairment • Vision impairment • Advanced age • History of alcohol abuse • Additional in palliative care population • Poor nutrition • Chronic renal disease. Inouye, Lancet Psychiatry, 2014; Bush, Drugs, 2017

Causes: The List is Very Long • Primary cerebral disease • Systemic disease affecting the brain secondarily--especially infections, electrolyte abnormalities (Na+, hyper Ca++, end organ disease (kidney, liver, lung) • Intoxication with exogenous substances (prescribed and illegal drugs) • Withdrawal from substances of abuse

Drug Causes of Delirium • The big three • Opioids • Benzodiazepines • Anticholinergics Others sometimes implicated • Corticosteroids • Dopaminergic agonists • Anticonvulsants • Quinolone antibiotics Bush, Drugs, 2017

Evaluation of Delirium • Maintain safety • Search for causes • Manage symptoms

Evaluation of Delirium • Measure of cognition • Evaluation for behavioral problems, suicidality, elopement risk • Review medications, alcohol and benzo use • Assess for pain, discomfort, sensory impairments • CBC, lytes, BUN/Cr, glucose, Ca, LFTs, TFTs, UA, drugs levels, CXR • Consider ABG, B 12, UDS, ECG

Evaluation of delirium • LP if fever, headache, meningeal signs • Neuroimaging if focal changes, history of head trauma • EEG for seizures, to differentiate psychiatric conditions

Interventions for Delirium—Research Issues • Very difficult clinical trials to perform—issues of consent, heterogeneity of causes, lack of generalizability • Prevention versus treatment • Measurement of outcome— • development of delirium (incidence) • severity of delirium • length of delirium • adverse outcomes of delirium • severity of behavioral issues • Length of hospital stay • Differences in site • ICU • palliative care • post operative

Non pharmacological interventions Two types • Proactive geriatric consultation for patients at risk of developing delirium • Multicomponent interventions • Effective to prevent delirium, but more limited impact on established delirium (Abraha, 2015, PLOS ONE) • Generally safe • Cognitive remediation and early mobilization, however, may worsen agitation and distress (Meagher, Int J Geriatr Psychiaty 2017) • May be costly if delivered by specialized teams

Management of delirium—Non pharmacological approaches • Remove psychoactive drugs • Maintain hydration and nutrition • Encourage family involvement • Therapeutic companion for safety issues • Eye glasses and hearing aids • Ambulate patients • Facilitate awake during day, sleep at nigh • Quiet room, low level light • Avoid restraints and bed alarms • Inouye, Lancet Psychiatry, 2014

Melatonin agonists for prevention and treatment • 145 elderly individuals admitted through ED to medical unit—included prevalent delirium (Al-Aama Int J geriatr Psych, 2011) • Statistically lower occurrence of delirium with melatonin • Not intention to treat • Small (N = 67) study of ramelteon for prevention of delirium in ICU patients (Hatta, Jama Psychiatry 2014) • Non blinded, obvious differences in look of placebo and ramelteon. • Statistically lower incidence of delirium with ramelteon • A large (452 patients) well done study of patients with hip fracture (de jonghe CMAJ, 2014) • Half of the patients had premorbid dementia • No effect on incidence of delirium, mortality, or three month cognitive or functional outcomes. • Melatonin group had fewer patients with prolonged delirium

Melatonin • Advantages • Inexpensive (21 cents per 3 mg pill) • Single daily dose of 3 mg at bedtime • Minimal adverse effects • Adverse effects • Dizzyness • Headache • Short term low mood • Morning sleepiness • Irritability • Abdominal cramps Drug interactions Warfarin Four large trials underway—more definitive answers to effectiveness pending

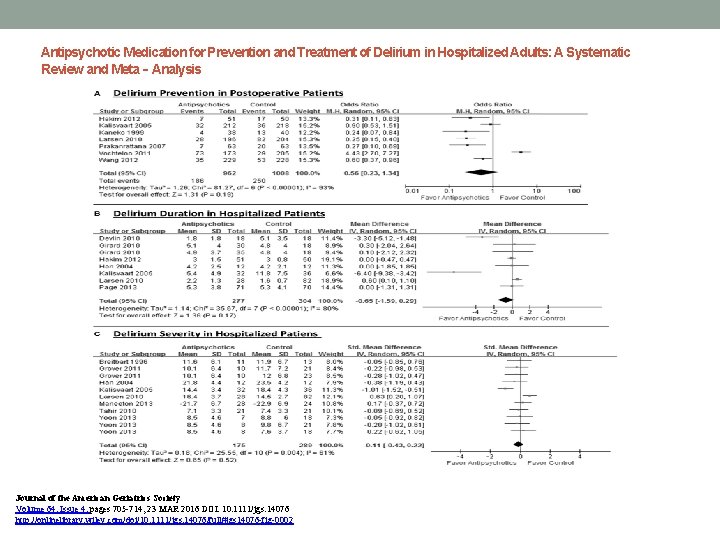

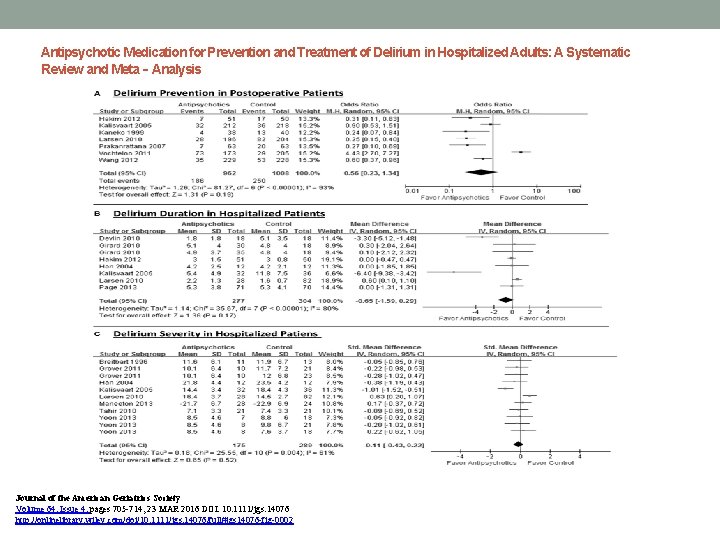

Antipsychotic Medication for Prevention and Treatment of Delirium in Hospitalized Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta‐Analysis Journal of the American Geriatrics Society Volume 64, Issue 4, pages 705 -714, 23 MAR 2016 DOI: 10. 1111/jgs. 14076 http: //onlinelibrary. wiley. com/doi/10. 1111/jgs. 14076/full#jgs 14076 -fig-0002

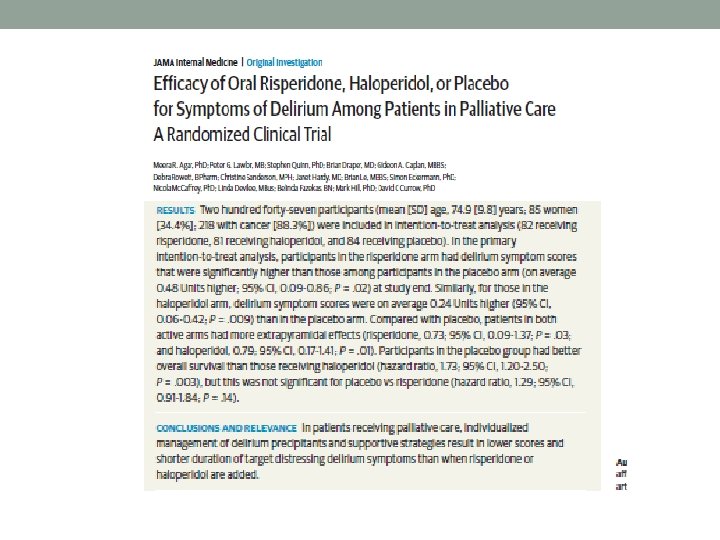

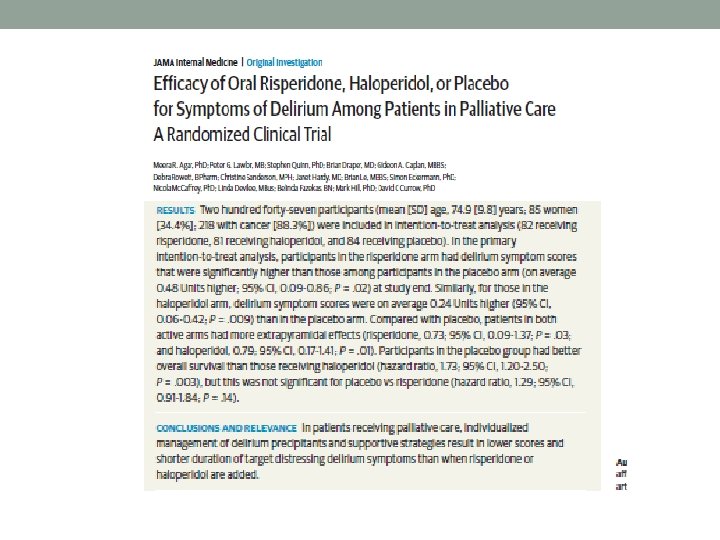

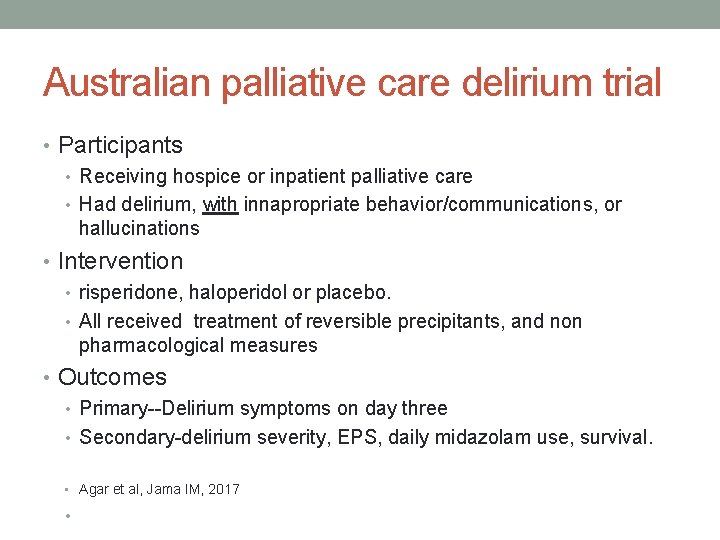

Australian palliative care delirium trial • Participants • Receiving hospice or inpatient palliative care • Had delirium, with innapropriate behavior/communications, or hallucinations • Intervention • risperidone, haloperidol or placebo. • All received treatment of reversible precipitants, and non pharmacological measures • Outcomes • Primary--Delirium symptoms on day three • Secondary-delirium severity, EPS, daily midazolam use, survival. • Agar et al, Jama IM, 2017 •

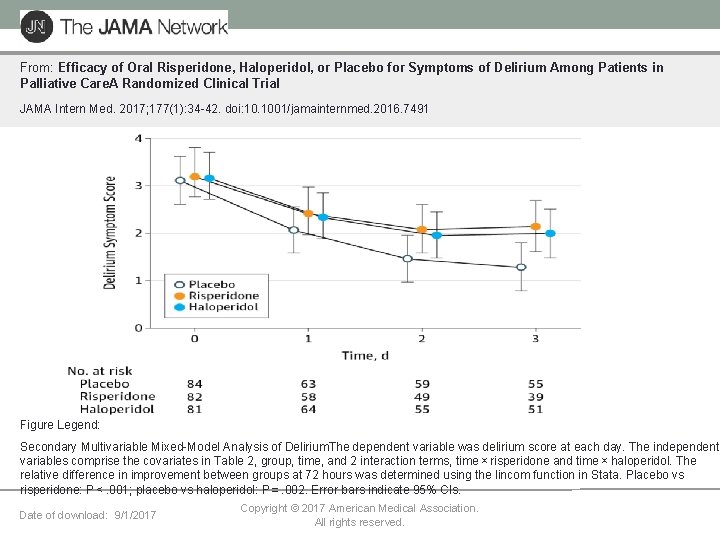

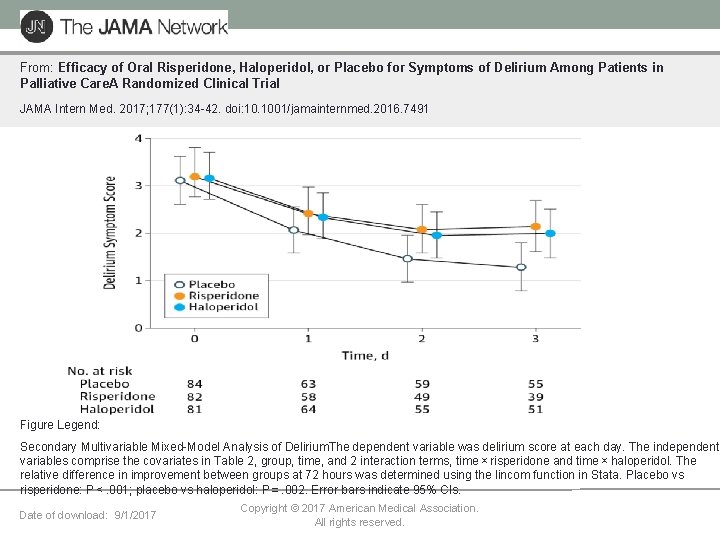

From: Efficacy of Oral Risperidone, Haloperidol, or Placebo for Symptoms of Delirium Among Patients in Palliative Care. A Randomized Clinical Trial JAMA Intern Med. 2017; 177(1): 34 -42. doi: 10. 1001/jamainternmed. 2016. 7491 Figure Legend: Secondary Multivariable Mixed-Model Analysis of Delirium. The dependent variable was delirium score at each day. The independent variables comprise the covariates in Table 2, group, time, and 2 interaction terms, time × risperidone and time × haloperidol. The relative difference in improvement between groups at 72 hours was determined using the lincom function in Stata. Placebo vs risperidone: P < . 001; placebo vs haloperidol: P = . 002. Error bars indicate 95% CIs. Date of download: 9/1/2017 Copyright © 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Australian palliative care delirium trial—Main findings • 247 participants, 88% with cancer • Baseline—haloperidol group had more severe baseline delirium and great • • opioid use. Greater delirium symptom scores and longer duration of delirium in both antipsychotic treated groups. Less rescue medication (midazolam) in placebo group. Higher mortality in antipsychotic treated groups—statistically significant in the haloperidol group (similarly finding in large studies of antipsychotics for dementia) Overall higher EPS in antipsychotic groups. Tendency for placebo group to improve may reflect regression to mean or efficacy of non pharmacological interventions. • Agar et al, Jama IM, 2017

Antipsychotic adverse effects • Drug- induced parkinsonism • • Comes on over days dose related Increased risk of falls, reduced bed mobility Common with haloperidol and risperidone • • uncomfortable restlessness that may worsen agitation. Comes on quickly, dose related Occurs in about 10% • Akathisia • Orthostatic hypotension • Increased risk of falls • Quetiapine, risperidone, olanzapine • QT prolongation • Increased with IV haloperidol • Unusual with low dose oral preparations • But avoid of QTC greater than 500 ms

Other negative trials for delirium • Benzodiazepines • Causes delirium and worsens delirium severity, falls • Only use when goals of care no longer include clarity of thinking and patient no longer ambulatory • Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors such as rivastigmine and donepezil • Five trials, all negative. • Regional versus general anesthesia • Two trials, both negative • Dexmedetomidine in intubated ICU patients • Four trials, lower delirium compared to midazolam, propofol, or morphine, but mostly not relevant to hospice and palliative care • Friedman et al, Am J Psychiatry 2014

Summary • Delirium most common mental disorder at end of life • Often misdiagnosed as depression or ignored • Permissive approach probably increases suffering, but workup must be • • • balanced against burdens, likelihood of reversal Very distressing for patients and family Non-pharmacological treatments are recommended for prevention Melatonin has uncertain efficacy, but fewer adverse effects than antipsychotics Do not use antipsychotics routinely • Preserve for severe agitation, psychosis or hallucinations (NICE guidelines, 2010) In some cases palliative sedation needed