Universal Hash Families Universal hash families Family of

- Slides: 28

Universal Hash Families

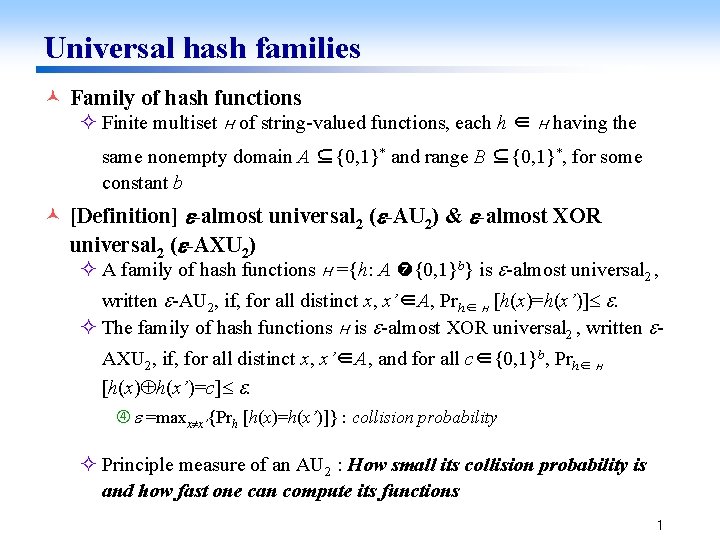

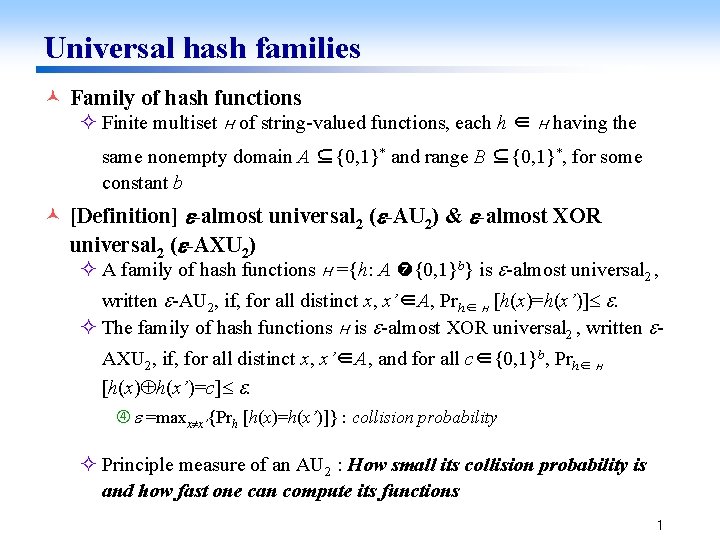

Universal hash families © Family of hash functions ² Finite multiset H of string-valued functions, each h ∈ H having the same nonempty domain A ⊆{0, 1}* and range B ⊆{0, 1}*, for some constant b © [Definition] -almost universal 2 ( -AU 2) & -almost XOR universal 2 ( -AXU 2) ² A family of hash functions H ={h: A {0, 1}b} is -almost universal 2 , written -AU 2, if, for all distinct x, x’∈A, Prh∈ H [h(x)=h(x’)] . ² The family of hash functions H is -almost XOR universal 2 , written AXU 2, if, for all distinct x, x’∈A, and for all c∈{0, 1}b, Prh∈ H [h(x) h(x’)=c] . =maxx x’{Prh [h(x)=h(x’)]} : collision probability ² Principle measure of an AU 2 : How small its collision probability is and how fast one can compute its functions 1

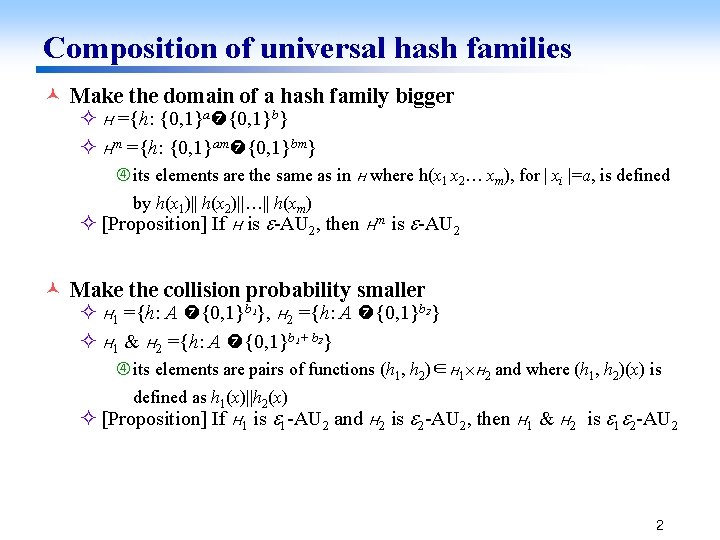

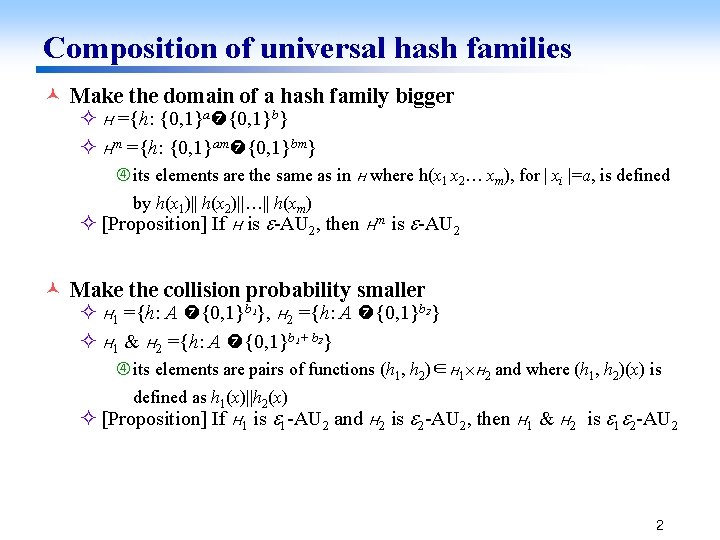

Composition of universal hash families © Make the domain of a hash family bigger ² H ={h: {0, 1}a {0, 1}b} ² Hm ={h: {0, 1}am {0, 1}bm} its elements are the same as in H where h(x 1 x 2… xm), for | xi |=a, is defined by h(x 1)|| h(x 2)||…|| h(xm) ² [Proposition] If H is -AU 2, then Hm is -AU 2 © Make the collision probability smaller ² H 1 ={h: A {0, 1}b 1}, H 2 ={h: A {0, 1}b 2} ² H 1 & H 2 ={h: A {0, 1}b 1+ b 2} its elements are pairs of functions (h 1, h 2)∈H 1 H 2 and where (h 1, h 2)(x) is defined as h 1(x)||h 2(x) ² [Proposition] If H 1 is 1 -AU 2 and H 2 is 2 -AU 2, then H 1 & H 2 is 1 2 -AU 2 2

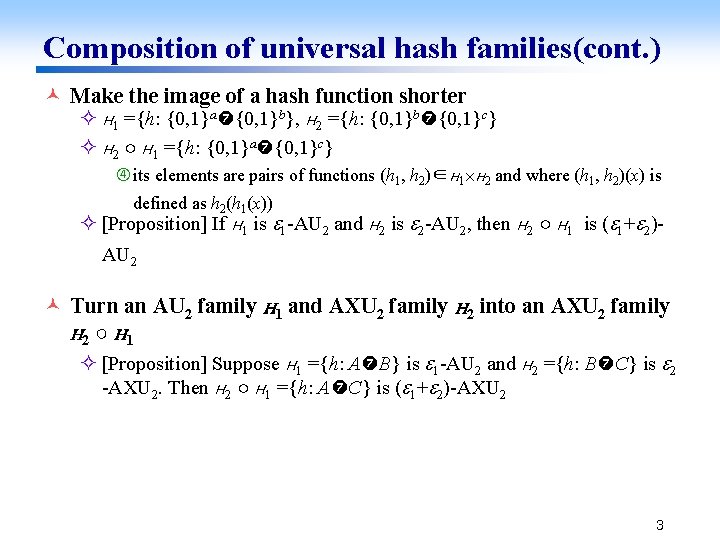

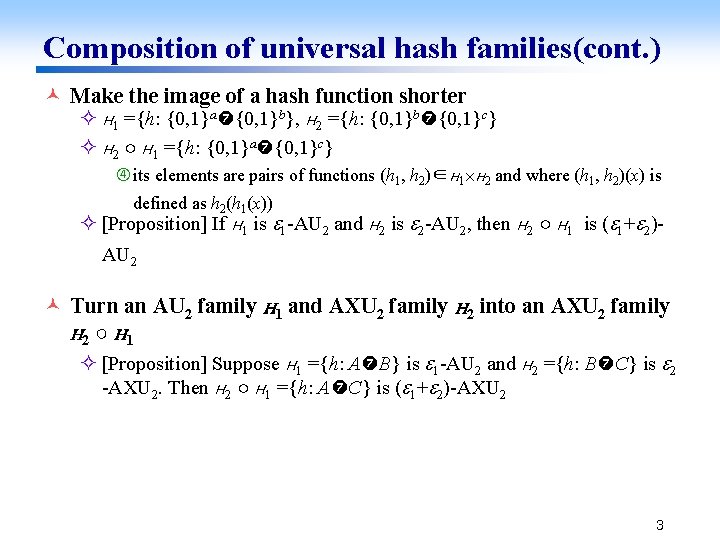

Composition of universal hash families(cont. ) © Make the image of a hash function shorter ² H 1 ={h: {0, 1}a {0, 1}b}, H 2 ={h: {0, 1}b {0, 1}c} ² H 2 ○ H 1 ={h: {0, 1}a {0, 1}c} its elements are pairs of functions (h 1, h 2)∈H 1 H 2 and where (h 1, h 2)(x) is defined as h 2(h 1(x)) ² [Proposition] If H 1 is 1 -AU 2 and H 2 is 2 -AU 2, then H 2 ○ H 1 is ( 1+ 2)AU 2 © Turn an AU 2 family H 1 and AXU 2 family H 2 into an AXU 2 family H 2 ○ H 1 ² [Proposition] Suppose H 1 ={h: A B} is 1 -AU 2 and H 2 ={h: B C} is 2 -AXU 2. Then H 2 ○ H 1 ={h: A C} is ( 1+ 2)-AXU 2 3

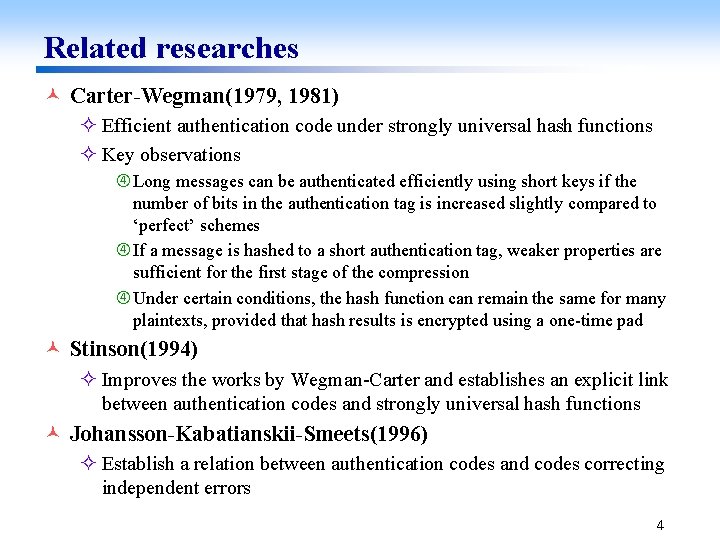

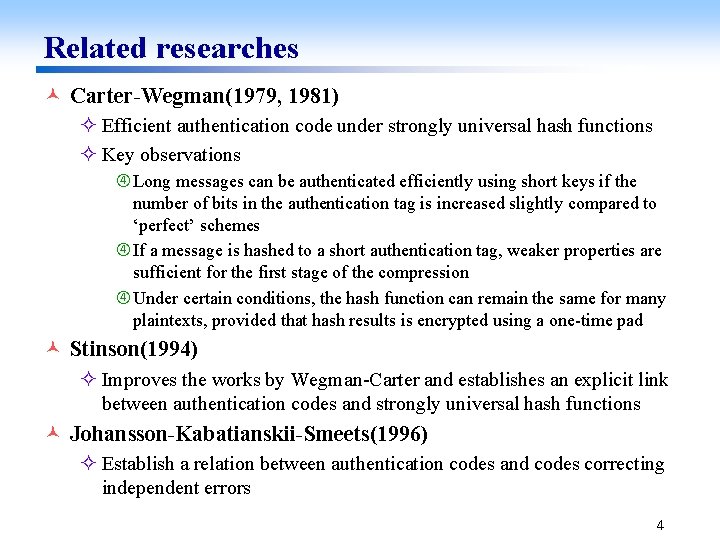

Related researches © Carter-Wegman(1979, 1981) ² Efficient authentication code under strongly universal hash functions ² Key observations Long messages can be authenticated efficiently using short keys if the number of bits in the authentication tag is increased slightly compared to ‘perfect’ schemes If a message is hashed to a short authentication tag, weaker properties are sufficient for the first stage of the compression Under certain conditions, the hash function can remain the same for many plaintexts, provided that hash results is encrypted using a one-time pad © Stinson(1994) ² Improves the works by Wegman-Carter and establishes an explicit link between authentication codes and strongly universal hash functions © Johansson-Kabatianskii-Smeets(1996) ² Establish a relation between authentication codes and codes correcting independent errors 4

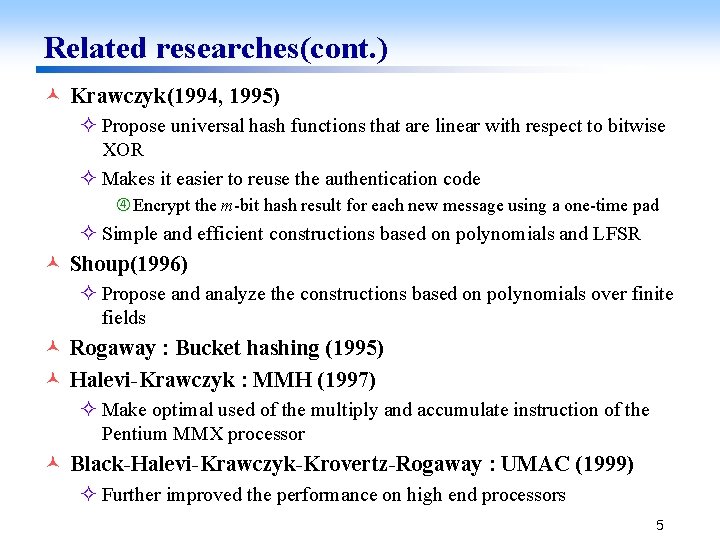

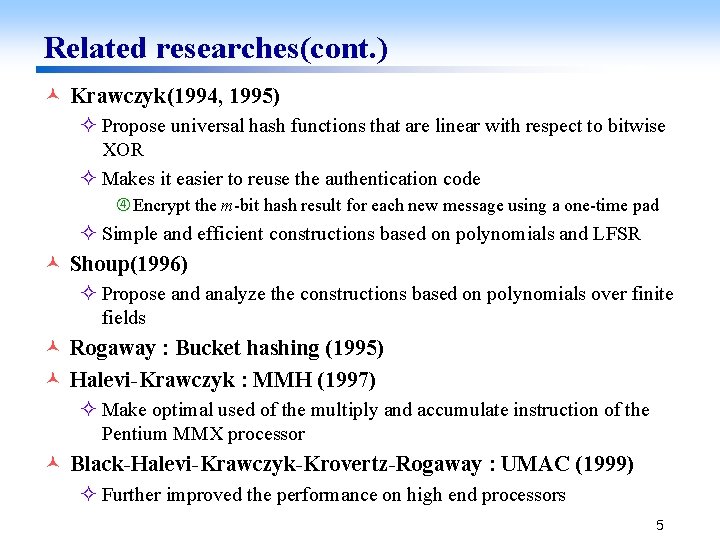

Related researches(cont. ) © Krawczyk(1994, 1995) ² Propose universal hash functions that are linear with respect to bitwise XOR ² Makes it easier to reuse the authentication code Encrypt the m-bit hash result for each new message using a one-time pad ² Simple and efficient constructions based on polynomials and LFSR © Shoup(1996) ² Propose and analyze the constructions based on polynomials over finite fields © Rogaway : Bucket hashing (1995) © Halevi-Krawczyk : MMH (1997) ² Make optimal used of the multiply and accumulate instruction of the Pentium MMX processor © Black-Halevi-Krawczyk-Krovertz-Rogaway : UMAC (1999) ² Further improved the performance on high end processors 5

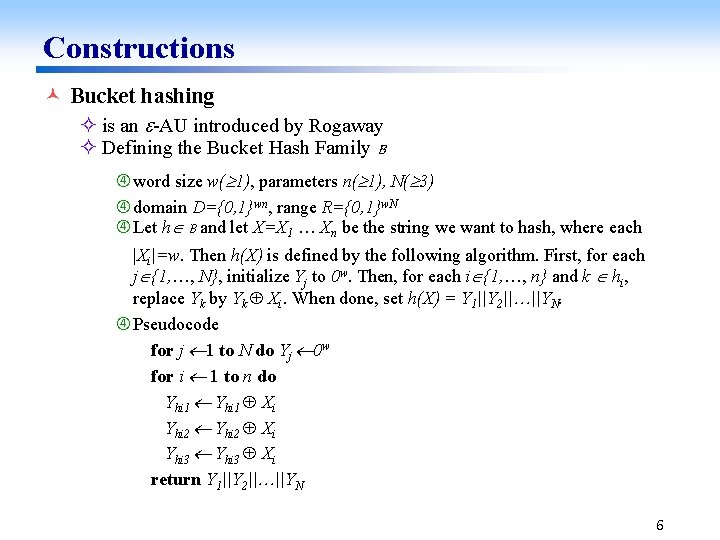

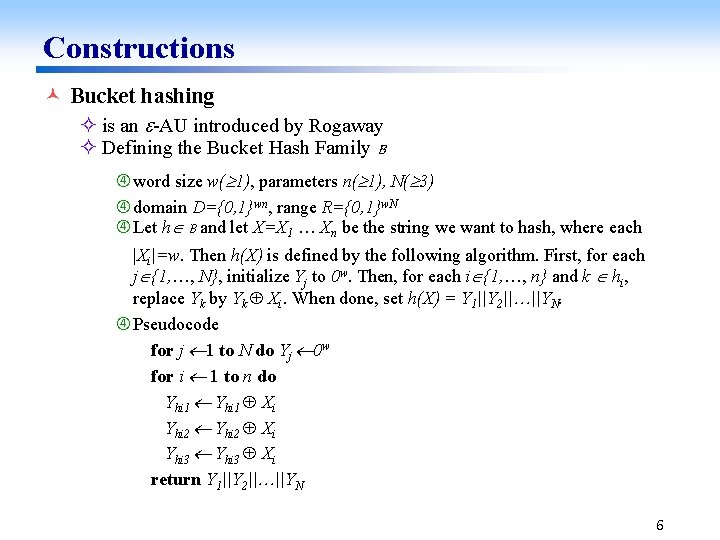

Constructions © Bucket hashing ² is an -AU introduced by Rogaway ² Defining the Bucket Hash Family B word size w( 1), parameters n( 1), N( 3) domain D={0, 1}wn, range R={0, 1}w. N Let h B and let X=X 1 Xn be the string we want to hash, where each |Xi|=w. Then h(X) is defined by the following algorithm. First, for each j {1, , N}, initialize Yj to 0 w. Then, for each i {1, , n} and k hi, replace Yk by Yk Xi. When done, set h(X) = Y 1||Y 2|| ||YN. Pseudocode for j 1 to N do Yj 0 w for i 1 to n do Yhi 1 Xi Yhi 2 Xi Yhi 3 Xi return Y 1||Y 2|| ||YN 6

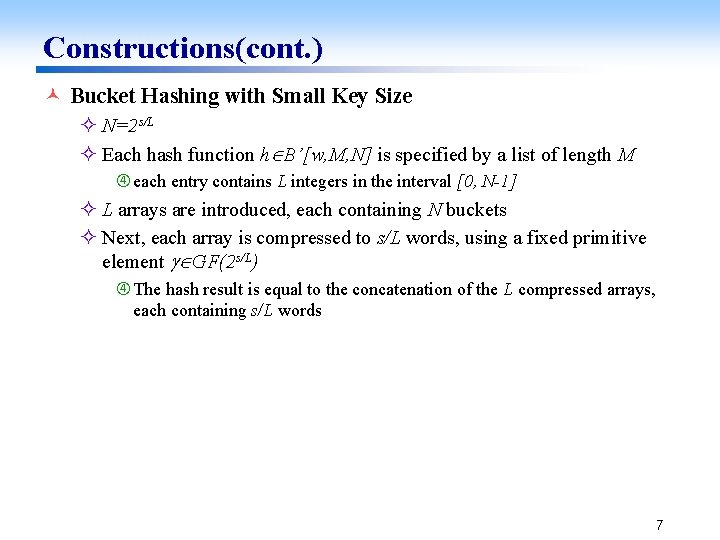

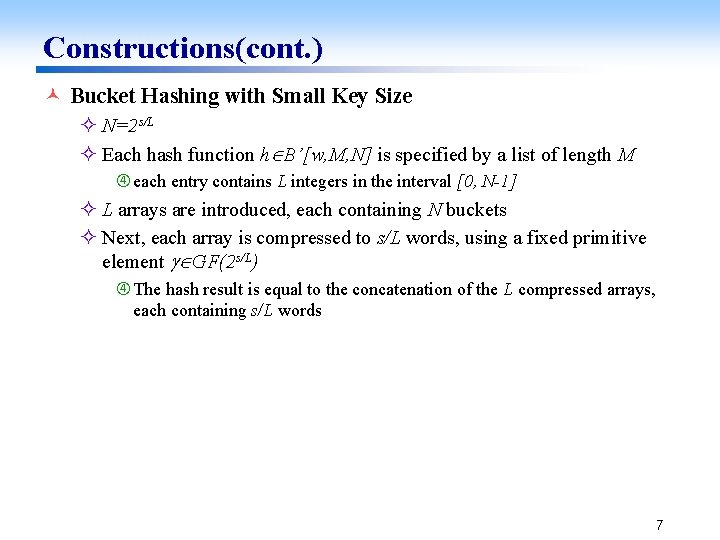

Constructions(cont. ) © Bucket Hashing with Small Key Size ² N=2 s/L ² Each hash function h B’[w, M, N] is specified by a list of length M each entry contains L integers in the interval [0, N-1] ² L arrays are introduced, each containing N buckets ² Next, each array is compressed to s/L words, using a fixed primitive element GF(2 s/L) The hash result is equal to the concatenation of the L compressed arrays, each containing s/L words 7

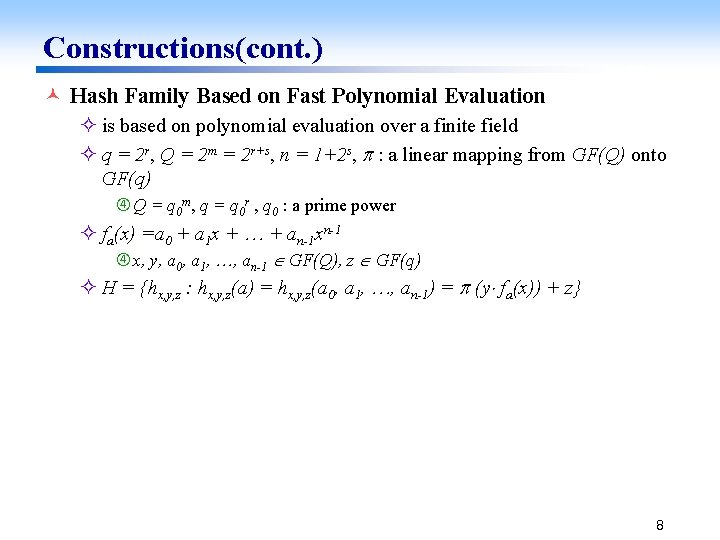

Constructions(cont. ) © Hash Family Based on Fast Polynomial Evaluation ² is based on polynomial evaluation over a finite field ² q = 2 r, Q = 2 m = 2 r+s, n = 1+2 s, : a linear mapping from GF(Q) onto GF(q) Q = q 0 m, q = q 0 r , q 0 : a prime power ² fa(x) =a 0 + a 1 x + + an-1 xn-1 x, y, a 0, a 1, , an-1 GF(Q), z GF(q) ² H = {hx, y, z : hx, y, z(a) = hx, y, z(a 0, a 1, , an-1) = (y fa(x)) + z} 8

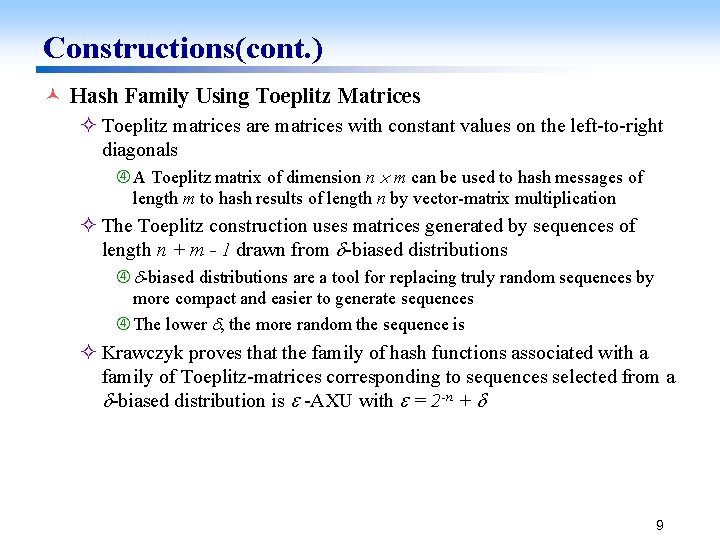

Constructions(cont. ) © Hash Family Using Toeplitz Matrices ² Toeplitz matrices are matrices with constant values on the left-to-right diagonals A Toeplitz matrix of dimension n m can be used to hash messages of length m to hash results of length n by vector-matrix multiplication ² The Toeplitz construction uses matrices generated by sequences of length n + m - 1 drawn from -biased distributions are a tool for replacing truly random sequences by more compact and easier to generate sequences The lower , the more random the sequence is ² Krawczyk proves that the family of hash functions associated with a family of Toeplitz-matrices corresponding to sequences selected from a -biased distribution is -AXU with = 2 -n + 9

Constructions(cont. ) © Evaluation Hash Function ² is one of the variants analyzed by Shoup ² The input (of length tn) : viewed as a polynomial M(x) of degree < t over GF(2 n) ² The key : a random element GF(2 n) ² the hash result : equal to M( ) GF(2 n) ² This family of hash functions is -AXU with = t/2 n 10

Constructions(cont. ) © Division Hash Function ² represents the input as a polynomial M(x) of degree less than tn over GF(2) ² The hash key : a random irreducible polynomial p(x) of degree n over GF(2) ² The hash result : m(x) xn mod p(x) ² This family of hash functions is -AXU with = tn/2 n The total number of irreducible polynomials of degree n is roughly equal to 2 n/n 11

Constructions(cont. ) © MMH(Multilinear Modular Hashing) hashing ² consists of a (modified) inner product between message and key modulo a prime p (close to 2 w, with w the word length; below w = 32) ² is an -AXU 2, but with xor replaced by subtraction modulo p The core hash function maps 32 32 -bit message words and 32 32 -bit key words to a 32 -bit result The key size is 1024 bits and = 1. 5/ 230 For larger messages, a tree construction can be used the value of and the key length have to be multiplied by the height of the tree ² This algorithm is very fast on the Pentium Pro, which has a multiply and accumulate instruction On a 32 -bit machine, MMH requires only 2 instructions per byte for a 32 bit result 12

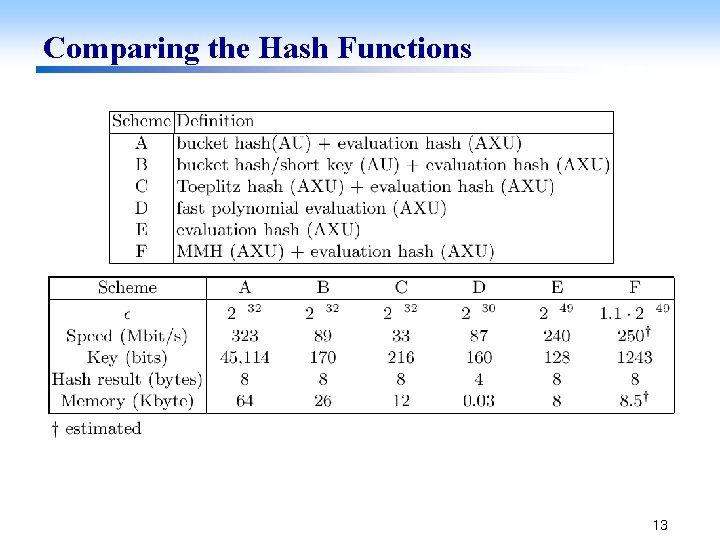

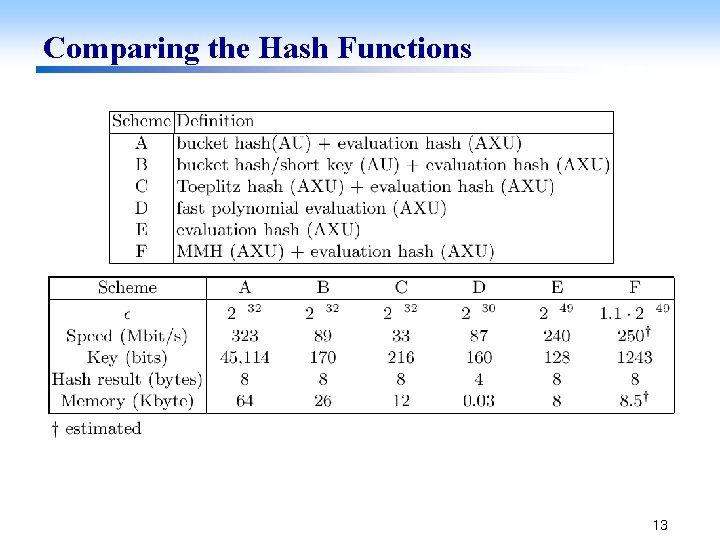

Comparing the Hash Functions 13

Comparing the Hash Functions(cont. ) © Scheme A ² the input : divided into 32 blocks of 8 Kbyte each block is hashed using the same bucket hash function with N = 160 results in an intermediate string of 20480 bytes © Scheme B ² the input : divided into 64 blocks of 4 Kbyte each block is hashed using the same bucket hash function with short key(s=42, L=6, N=128) results in an intermediate string of 10752 bytes © Scheme C ² the input is divided into 64 blocks of 4 Kbyte each block is hashed using a 33 1024 Toeplitz matrix, based on a -biased sequence of length 1056 generated using an 88 -bit LFSR The length of the intermediate string is 8448 bytes 14

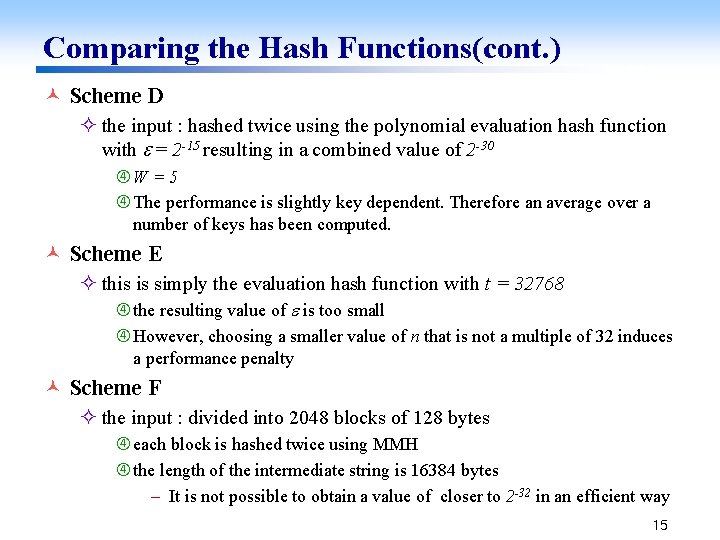

Comparing the Hash Functions(cont. ) © Scheme D ² the input : hashed twice using the polynomial evaluation hash function with = 2 -15 resulting in a combined value of 2 -30 W = 5 The performance is slightly key dependent. Therefore an average over a number of keys has been computed. © Scheme E ² this is simply the evaluation hash function with t = 32768 the resulting value of is too small However, choosing a smaller value of n that is not a multiple of 32 induces a performance penalty © Scheme F ² the input : divided into 2048 blocks of 128 bytes each block is hashed twice using MMH the length of the intermediate string is 16384 bytes – It is not possible to obtain a value of closer to 2 -32 in an efficient way 15

Universal Hashing MAC

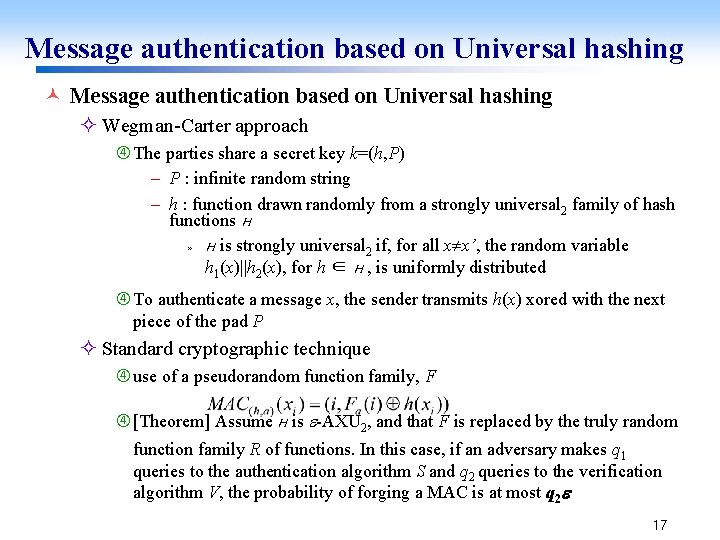

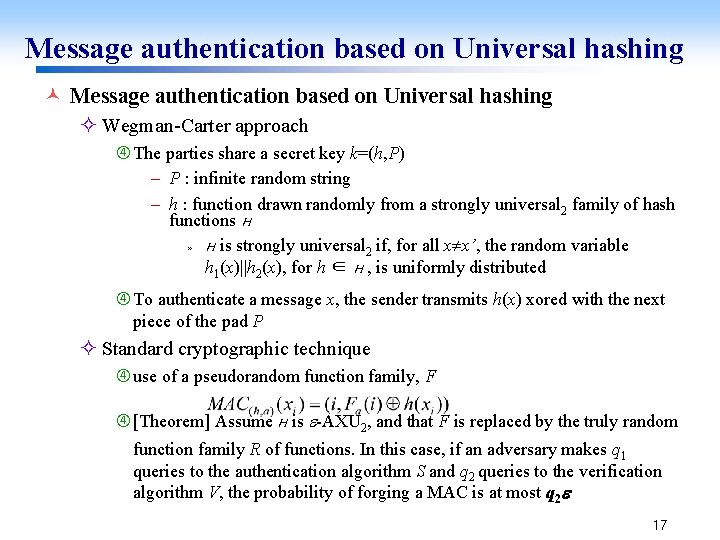

Message authentication based on Universal hashing © Message authentication based on Universal hashing ² Wegman-Carter approach The parties share a secret key k=(h, P) – P : infinite random string – h : function drawn randomly from a strongly universal 2 family of hash functions H » H is strongly universal 2 if, for all x x’, the random variable h 1(x)||h 2(x), for h ∈ H , is uniformly distributed To authenticate a message x, the sender transmits h(x) xored with the next piece of the pad P ² Standard cryptographic technique use of a pseudorandom function family, F [Theorem] Assume H is -AXU 2, and that F is replaced by the truly random function family R of functions. In this case, if an adversary makes q 1 queries to the authentication algorithm S and q 2 queries to the verification algorithm V, the probability of forging a MAC is at most q 2 17

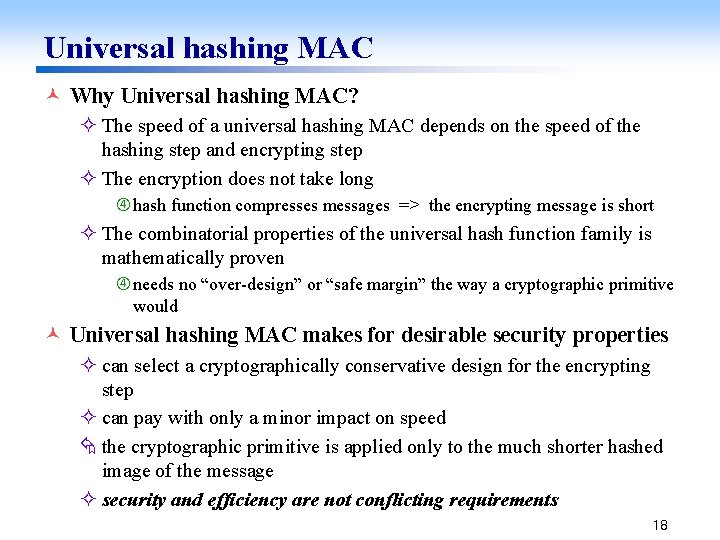

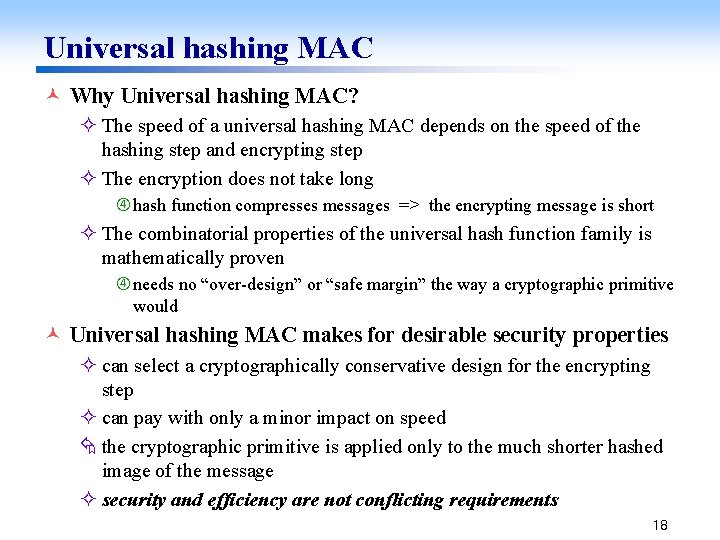

Universal hashing MAC © Why Universal hashing MAC? ² The speed of a universal hashing MAC depends on the speed of the hashing step and encrypting step ² The encryption does not take long hash function compresses messages => the encrypting message is short ² The combinatorial properties of the universal hash function family is mathematically proven needs no “over-design” or “safe margin” the way a cryptographic primitive would © Universal hashing MAC makes for desirable security properties ² can select a cryptographically conservative design for the encrypting step ² can pay with only a minor impact on speed Å the cryptographic primitive is applied only to the much shorter hashed image of the message ² security and efficiency are not conflicting requirements 18

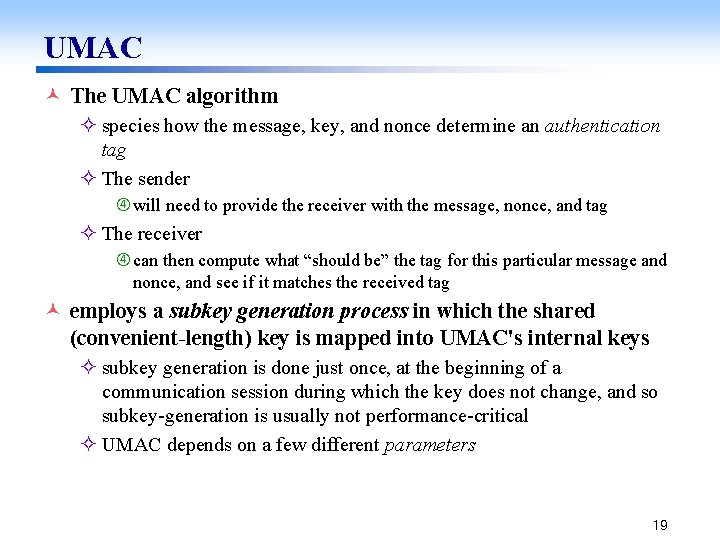

UMAC © The UMAC algorithm ² species how the message, key, and nonce determine an authentication tag ² The sender will need to provide the receiver with the message, nonce, and tag ² The receiver can then compute what “should be” the tag for this particular message and nonce, and see if it matches the received tag © employs a subkey generation process in which the shared (convenient-length) key is mapped into UMAC's internal keys ² subkey generation is done just once, at the beginning of a communication session during which the key does not change, and so subkey-generation is usually not performance-critical ² UMAC depends on a few different parameters 19

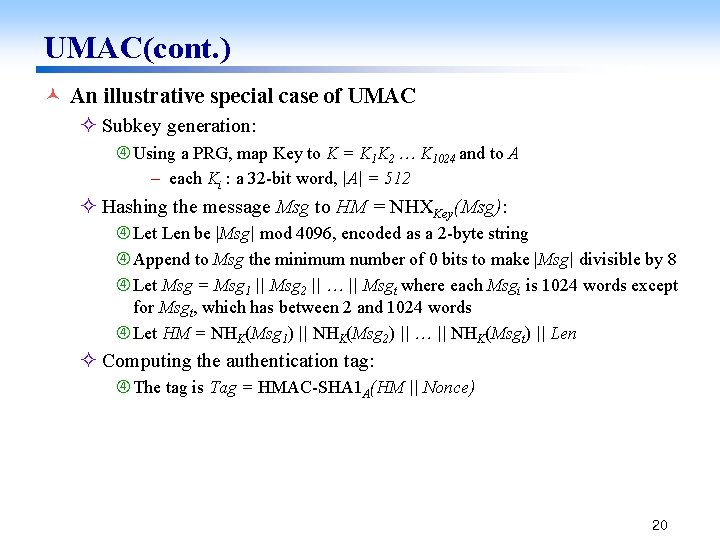

UMAC(cont. ) © An illustrative special case of UMAC ² Subkey generation: Using a PRG, map Key to K = K 1 K 2 K 1024 and to A – each Ki : a 32 -bit word, |A| = 512 ² Hashing the message Msg to HM = NHXKey(Msg): Let Len be |Msg| mod 4096, encoded as a 2 -byte string Append to Msg the minimum number of 0 bits to make |Msg| divisible by 8 Let Msg = Msg 1 || Msg 2 || Msgt where each Msgi is 1024 words except for Msgt, which has between 2 and 1024 words Let HM = NHK(Msg 1) || NHK(Msg 2) || NHK(Msgt) || Len ² Computing the authentication tag: The tag is Tag = HMAC-SHA 1 A(HM || Nonce) 20

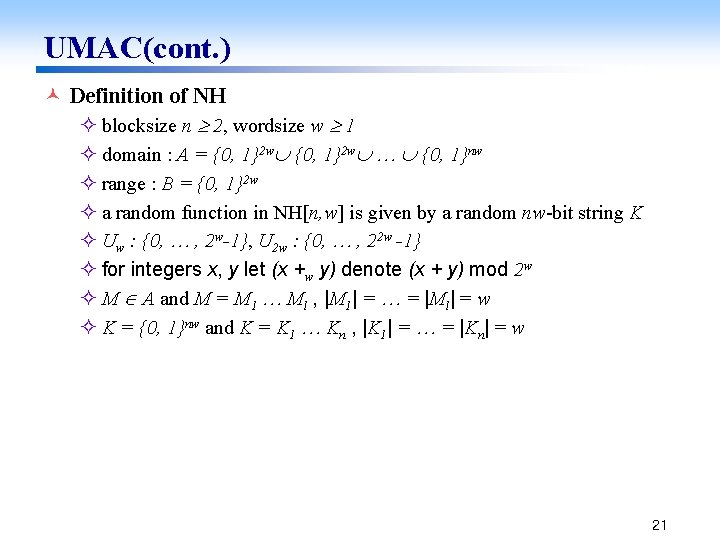

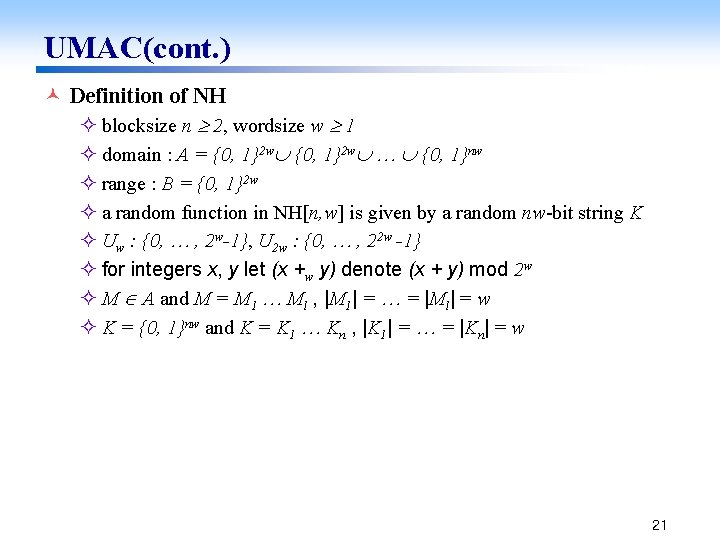

UMAC(cont. ) © Definition of NH ² blocksize n 2, wordsize w 1 ² domain : A = {0, 1}2 w {0, 1}nw ² range : B = {0, 1}2 w ² a random function in NH[n, w] is given by a random nw-bit string K ² Uw : {0, , 2 w-1}, U 2 w : {0, , 22 w -1} ² for integers x, y let (x +w y) denote (x + y) mod 2 w ² M A and M = M 1 Ml , |M 1| = = |Ml| = w ² K = {0, 1}nw and K = K 1 Kn , |K 1| = = |Kn| = w 21

UMAC(cont. ) ² where mi Uw is the number that Mi represents (as an unsigned integer) ² where ki Uw is the number that Ki represents (as an unsigned integer) ² the right-hand side of the above equation is understood to name the (unique) 2 w-bit string which represents (as an unsigned integer) the U 2 w -valued integer result 22

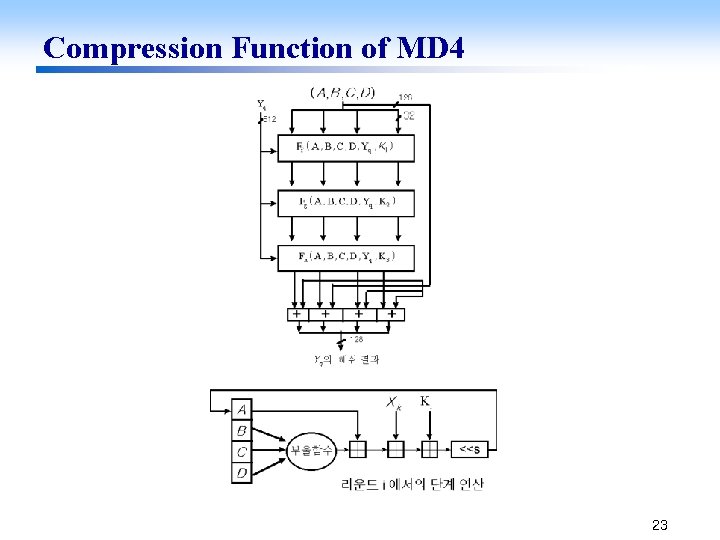

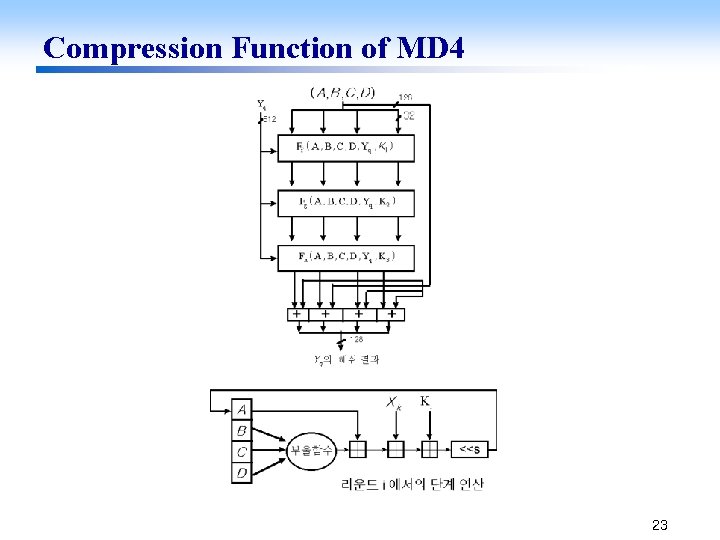

Compression Function of MD 4 23

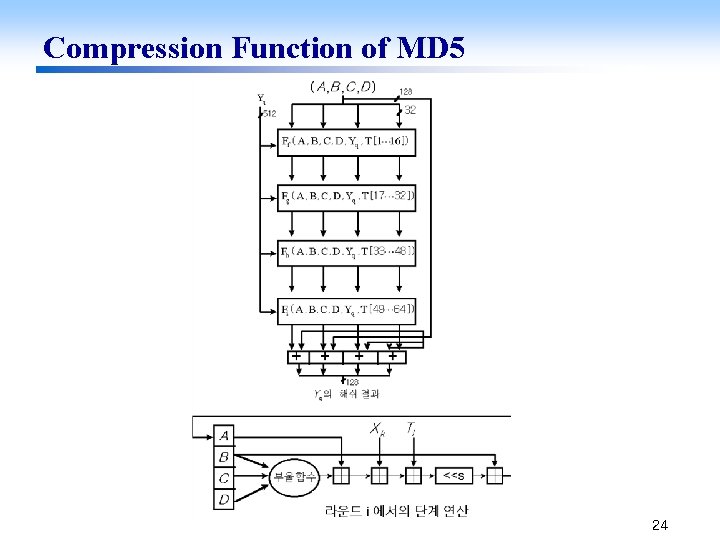

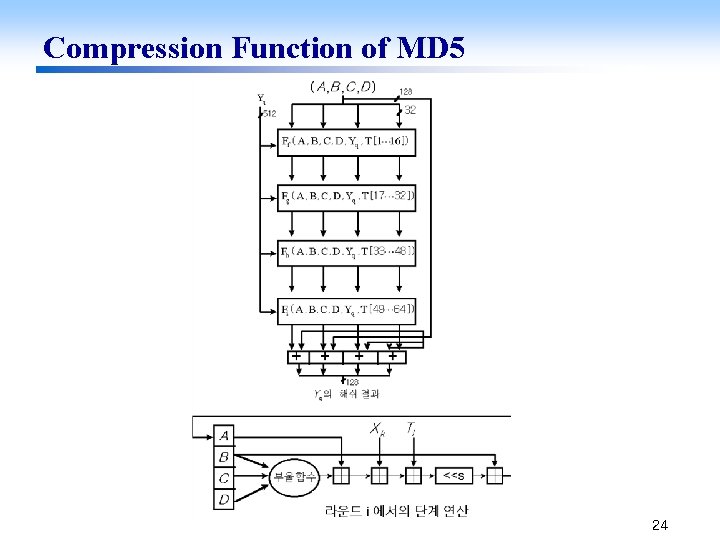

Compression Function of MD 5 24

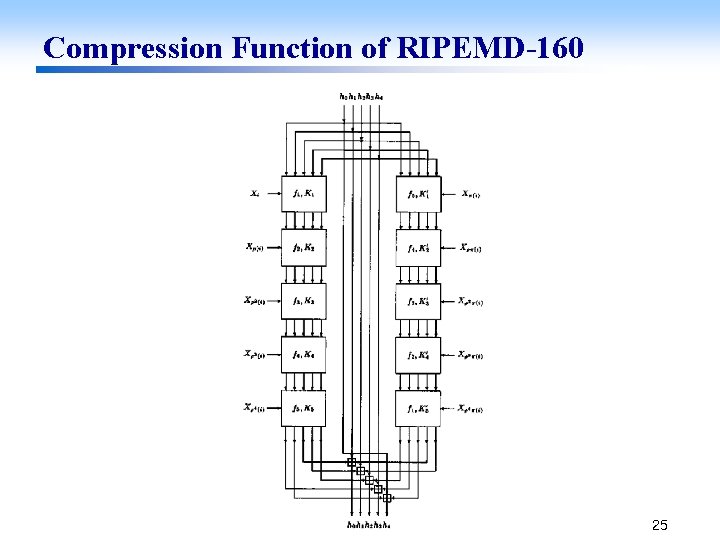

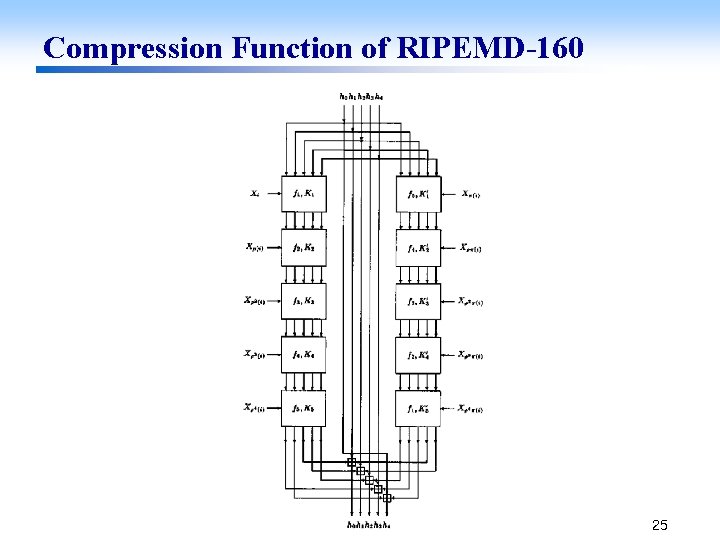

Compression Function of RIPEMD-160 25

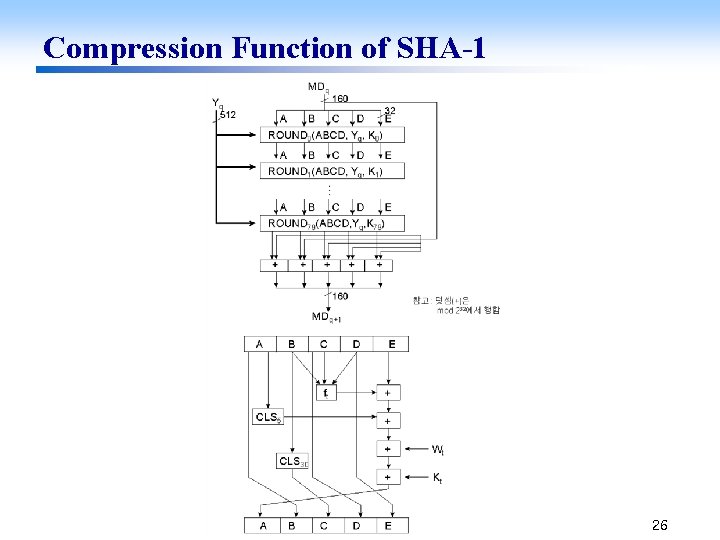

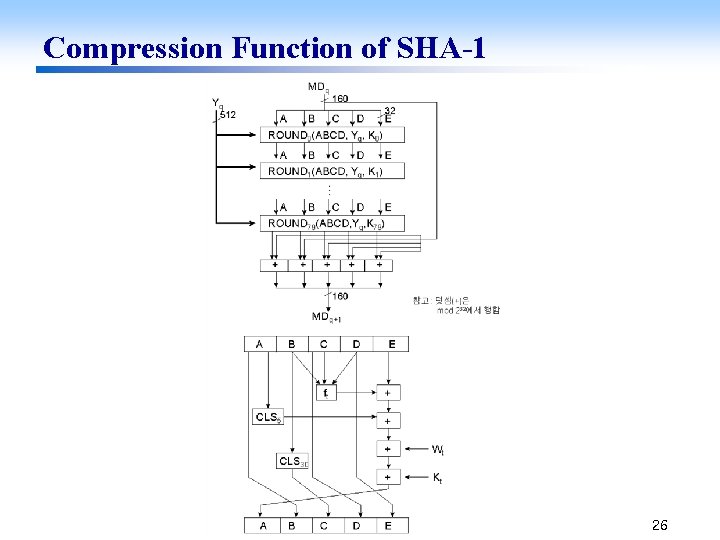

Compression Function of SHA-1 26

Conclusions